The article illuminates a research into several aspects of Gerard de Lairesse’s (1640–1711) painting technique. Ariadne and Bacchus was part of a series of decorative paintings for Soestdijk Palace, commissioned by Stadholder Willem III between 1676 and 1678. As part of an extensive restoration treatment of the painting during 2005 and 2006, descriptions in Lairesse’s Groot Schilderboek (1707) were studied. Two aspects of the writings were compared with the painting techniques, supported by paint sampling. The first aspect to be examined was the flesh colors of the figures Bacchus and Ariadne, because of their prominence in the picture. The second was atmospheric and color perspective, which raised questions about some parts of the picture.

Between 1674 and 1678 Gerard de Lairesse (Liéges 1640–1711 Amsterdam) executed a series of decorative paintings for Soestdijk Palace, commissioned by Stadholder Willem III (1650–1702). These works now belong to the collections of the Rijksmuseum and the Mauritshuis. In 2005 the restoration of Bacchus and Ariadne,1 one of the paintings in this series, prompted a research project on Lairesse’s painting technique (fig. 1).2

This study relies to a large extent on the Groot Schilderboek, which the artist wrote in 1707.3 In order to form a clear idea of the consistency of his own painting practice with the principles expounded in the treatise, several specific aspects are compared, including flesh colors and the use of atmospheric and color perspective. Lairesse dwells at length on these pictorial aspects of painting, while other matters—such as the support and the final varnish—receive little if any attention.

Although it is difficult to extract all the technical descriptions from the book, Lairesse fortunately describes the execution of a painting in a number of basic steps that recur throughout the book: “dead coloring,” “the second layer,” and “revision or retouching.”4 This threefold division was used to shed light on Lairesse’s painting technique, with the wider objective of improving our ability to interpret his paintings and to preserve them for the future.

Certain passages on technique in the book have been compared to the artist’s practical execution. This comparison includes other works in the same series as well as Bacchus and Ariadne. The study of the paint surface, the way the paint layers are built up, and the composition of the paint were all important for the purposes of this study.

In the descriptions and interpretations that are given below, additions and changes resulting from restorations have been left out of consideration, as far as is possible.

Soestdijk Palace

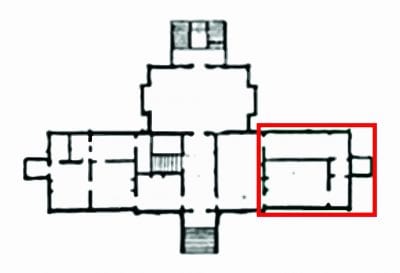

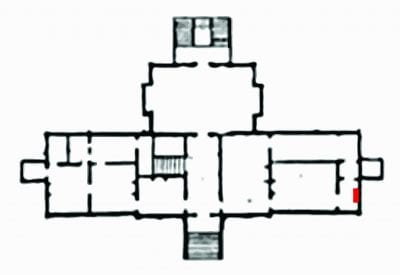

In 1674, Stadholder Willem III of Orange purchased a farmstead in Soestdijk from Jacob de Graeff. Between 1674 and 1678 he had the building converted into a hunting lodge by Maurits Post. Lairesse painted a series of mythological scenes for the apartments of the stadholder’s wife, Mary Stuart.5 They included several paintings for the bedroom of “Her Majesty”: a ceiling painting, two supraportes, and an overmantel painting. In addition in the study adjacent to the bedroom hung a supraporte and an overmantel painting by Lairesse (“een stuk schildrij voor de scheersteen van Larisse”). In view of the dimensions that are given, the latter must have been Bacchus and Ariadne.6

Since the stadholder purchased the land for his hunting lodge in 1674 and Lairesse was paid in 1678, we can assume that the entire series was painted in that four-year period.7

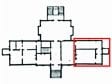

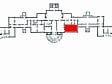

Mary Stuart’s apartments, which were on the ground floor in the central part of the front of the building, were altered between 1815 and 1821 as part of the renovation of the palace carried out by Jan de Greef (1784–1834). The study where Bacchus and Ariadne had hung was combined with the adjoining bedroom to form what is now the Waterloo Chamber.8 In consequence, we cannot learn from the site itself how or where the paintings hung. Old floor plans of the palace show the difference between the original room divisions and the later changes. The study had only a single window on the east of the front facade (figs. 2–3).9

We know that the walls of consequential rooms and halls were decorated. The wainscoting, added in the second half of the seventeenth century, extended to approximately 75 cm above the floor.10 Above it, large canvas paintings were inserted into the walls, which were architecturally articulated. Lairesse devotes a separate chapter of his book to this subject: “On making Wall paintings for interior spaces,”11 in which he compares the different roles of wall and ceiling paintings. Since the ceiling was associated with the soul, it was important to focus there on the spirit, which is ruled by Heaven. The subjects depicted on the walls, on the other hand, related to bodily existence and morality, which are governed by the faculty of reason.12 The choice of iconography depended on the intended location. Lairesse considers it essential for a viewer to be able to deduce this intended use from the decorations of each room or chamber. Besides the play of light and vantage point, the artist must also take the room’s architecture into consideration. Lairesse accords a prominent role to the overmantel painting:

Because the painting over the fireplace is the most important one of the room, I plan a figural composition in that place. A landscape would be inappropriate there, its horizon being outside the painting; far below it, even, which would mean that one could see nothing but the sky in that prominent place.13

Description of the Series

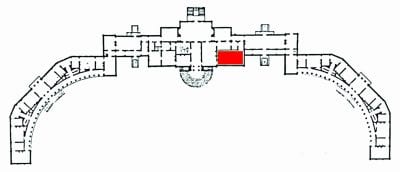

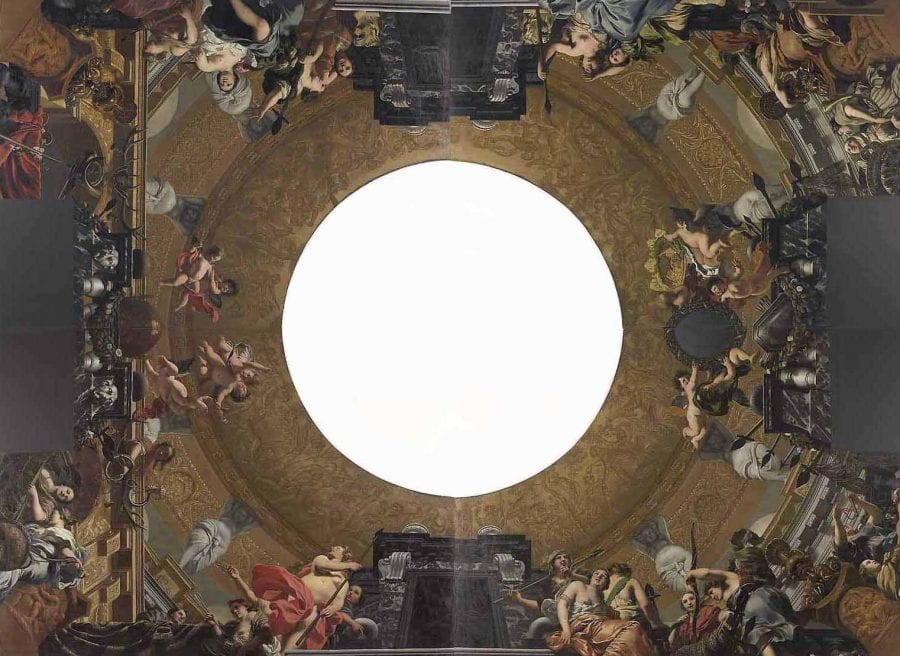

The commission granted to Gerard de Lairesse for Soestdijk Palace included—in addition to Bacchus and Ariadne—a “Five-part Ceiling Decoration for the Great Hall of Soestdijk Palace” (fig. 4).14 These paintings once embellished the ceiling of Mary Stuart’s bedroom. The dome, in trompe-l’oeil grisaille, is supported by caryatids whose feet rest on a painted balustrade. Seated on this balustrade are Diana’s companions with their hunting gear. The painting that originally featured in the center has been lost.15

Above the mantelpiece of the bedroom hung Selene and Endymion (fig. 5).16 The chastity of Diana and Selene was an exemplum virtutis for the bedroom of a young princess. Above the doors in the same room were two other paintings, Odysseus and Calypso and Mercury Ordering Calypso to Release Odysseus (figs. 6–7).17

Description and Iconography of Bacchus and Ariadne

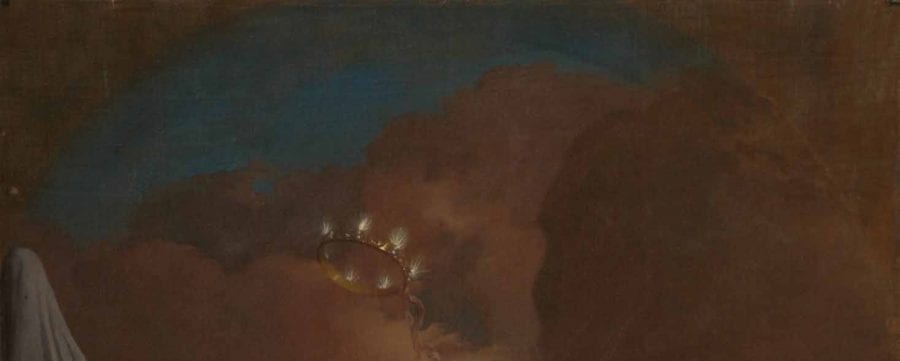

The story of Ariadne and Bacchus is depicted as related in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (see fig. 1). The painting shows the lovers Bacchus and Ariadne on the beach at Naxos. Bacchus has found the distraught Ariadne, following her abandonment by Theseus, and comforts her with his love: “And, that she might shine among the deathless stars, he sent the crown she wore up to the skies. Through the thin air it flew; and as it flew its gems were changed to gleaming fires.”18

In his Groot Schilderboek, Lairesse describes exactly how he painted this scene:19

I chose to depict her . . . with a sad face, with tear-filled eyes pointing at the sea and the faithless Theseus, the actual cause of her sadness. I showed Bacchus also, listening attentively, while Cupid opened his cloak to reveal whom she was confronted with. The god of love gradually uncovered his divinity and power, because Ariadne did not understand whom she was seeing, a man or a god.20

Bacchus and Ariadne are depicted side by side at the center of the image. On the left we see a canopy bed, embellished with a sphinx and purple drapery.21 On the right, Cupid is opening the red cloak of Bacchus. He holds a thyrsos, the attribute of Bacchus—a staff with a pinecone on top. In the right background we see Bacchantes and maenads with a tambourine and wine goblets.

Above the clouds is a blue sky painted in the shape of an arch, with the corners left unpainted.22 Like the other paintings in the series, this work must originally have hung in a frame or have been inserted into paneling that was semicircular at the top.23 On this subject Lairesse remarks: “There should be something under each beam, either a pilaster or a herm. If not, the painting should be arched at the top.”24

The foreshortening of the lower part of Bacchus’s body is probably intentional, with a view to the painting being hung high up above the mantelpiece. Ariadne’s upper body is turned at a slight angle in relation to the lower part of her body. Pentimenti are visible in both the ring finger of Bacchus’s hand and a finger of Ariadne’s left hand (fig. 8). Lairesse was evidently trying to find the right position of the hands.25 In the Groot Schilderboek, he describes the rules for positioning the hands: “The hands should always make contrasting movements. When the one shows its inside, the other one should be seen from the outside; when one is hanging down, the other one is drawn up.”26 The variation that Lairesse seeks to achieve in the hands – open and closed, turned and extended – explains why he eventually depicts the hand of Bacchus bent, above Ariadne’s hand with her fingers outstretched.27 Furthermore, it corresponds to the crown being cast upwards and slightly to the rear.28

Research into the Painting Technique of Bacchus and Ariadne

In the Prologue (Voorreden), Lairesse explains that the book serves as an instrument that will help someone without proper training to learn the art of painting. Even so, the book is not easy to consult. The text jumps back and forth between practical tips and useful knowledge for art connoisseurs and interested lay readers. Furthermore, it should be borne in mind when interpreting the texts of the Groot Schilderboek that Lairesse wrote the book after he had gone blind. His direct relationship with the practice of his art might have weakened with the years.29

To illuminate Lairesse’s painting technique, diverse research methods were used.30 The painting is described in the same order in which it was created, starting with the support and ending with the paint layers.

Support

Lairesse’s Groot Schilderboek pays no attention to the quality of the supports of the pictorial work. Bacchus and Ariadne was painted on a single canvas with a fine, dense plain weave.31 Both the left and right sides of the canvas have remnants of a selvedge. From this it can be concluded that the canvas came from a roll presumably measuring 97 cm in width.32

Ground

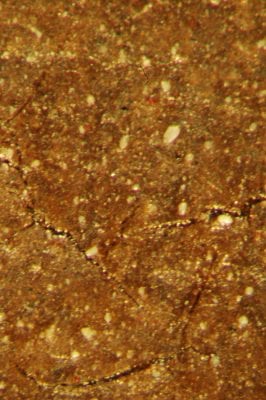

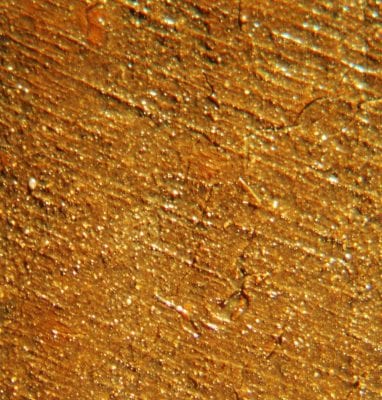

The canvas has been primed with a brown ground, composed of two layers.33 The ground has been applied across the entire surface of the stretched canvas and also covers the tacking edges. The ground is clearly visible in the top corners. The bottom layer consists of chalk and umber, both in large particles and as an extremely fine red earth pigment.34 Chalk was cheaper and lighter than lead white; it was often used to prime large canvases for decorative paintings. On top a second layer was applied, consisting of lead white, umber, and chalk. This layer is lighter in color and the umber particles are smaller. The lead white is present in a mix of coarse and finer particles. This is typical of the production process of lead white in this period. It was ground by hand into paint and hence there is a difference in particle size (fig. 9).35

The paint cross-sections show that the layers of ground have a highly uneven surface. This is attributable in part to the large particles of umber and chalk in the first layer, measuring 60 μm (fig. 10). Another noteworthy detail is the visible presence of brushstrokes in the upper corners, where the ground was left uncovered (fig. 11).

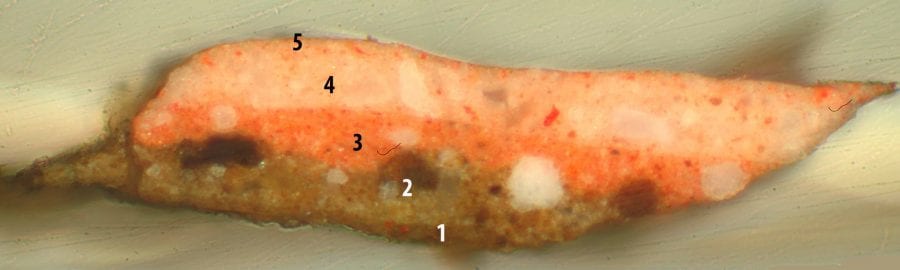

(5) Thin layer of lead white, chalk, and discolored smalt

(4) Layer of lead white, chalk, vermilion, red lake, yellow ochre, calcium phosphate, bone black

(3) Two layers of lead white and vermilion with a medium layer in between

(2) Ground layer with lead white, umber, and chalk

(1) Ground layer with umber, chalk. and red earth pigment [side-by-side viewer]

In his Groot Schilderboek, Lairesse advises artists to adapt the preparation of the ground to match the intended color of the final work of art. He distinguishes between priming for landscapes, rooms and other interiors, and night scenes. For the second category he advises a priming with umber. Depending on the composition of the painting, colors can be slightly modified.36 He continues to emphasize the qualities of a good priming:

When it is thoroughly dry, a priming [ground] of this kind has three positive qualities. Firstly, it is convenient, because it is even and dull, which makes the paint bind immediately, however thin it may be. It allows working tidily, which is much more difficult and time consuming on a smooth or shiny ground layer. Secondly, it is durable, because of its similarity to the gradations of darkness and colors put on top of it. They will keep their full beauty and strength, which is impossible when the priming has a different color or a different degree of darkness, such as white on black, light blue on dark yellow or red, et cetera. In the course of time the ground color will shine through more and more in those cases, however thickly the top layer may have been laid on. Thirdly, as I said before, it expedites the completion of your concept when your hand is steady and your brush is swift. Otherwise this would be impossible without dead coloring.37

Lairesse was not entirely consistent in his use of terminology, sometimes using the words for “ground” and “dead coloring”—the first layer of color—interchangeably.

In any case, Lairesse asserts that the ground must above all be opaque and provide grip for the paint layers to be applied afterward. This certainly applied in the case of the ground of Bacchus and Ariadne, the relatively coarse structure of which enabled the paint layers to adhere well.

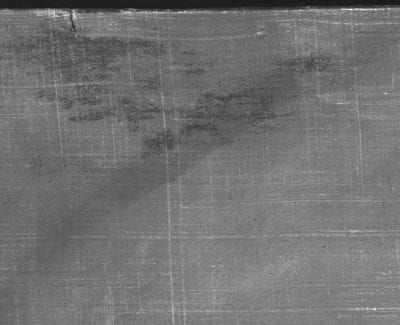

Underdrawing

The painting was examined using infrared reflectography to check for the presence of any underdrawing or undermodeling with carbonaceous material.38 This technique (IR-2) revealed the beginnings of an arch shape on the left in the sky section (fig. 12). A paint cross-section taken from this point revealed that a thin, very slightly fluorescent layer had been applied over the ground here, with fine black, red, and a little blue and extremely fine white pigment.39 The slight fluorescence may have been caused by the medium, or—if the fine white pigment is lead white—by the pigment itself. This layer is identical to that found in a paint cross-section taken from the purple draperies above the bed.40 This is also visible under infrared (IR-2) in the shape of a faint line (fig. 13). Here it is known that bone black and lead white were used.41

Aside from the places referred to above, no underdrawing or undermodeling is discernible. Nor indeed does Lairesse ever refer to such a practice in his treatise.42 On the basis of the two discoveries made in the sky section and the purple draperies, these appear rather to have belonged to the stage of dead coloring, which he included under the heading of “paint layers.”

Paint Layers

The paint has the appearance of oil paint. Although only the binding medium used in the sky section was analyzed, it is a reasonable assumption that the entire work was executed in paint based on linseed oil.43 The paint was applied thinly, wet-in-wet, in opaque and semitransparent layers. The artist rarely used impasto, with the exception of very minimal applications, as in the highlights of the wooden sphinx adorning the bed (fig. 14) He favored thin brushes for details such as the faces of the figures, and somewhat thicker ones for the draperies. In his book Lairesse refers to a soft vispenseel, a brush made from the whiskers of an otter, which he used for the scumbling and brushing out of highlights and shadows.44

In building up the representation in a painting, Lairesse distinguishes three stages: dead coloring, applying the second layer, and revision or retouching. From his description of the first stage, we can infer that different colors were used with the aim of producing an initial arrangement of the scene.45

To prevent that you labor in vain, you should give due attention to the overall houding.46 This means that the colors and their shades are arranged in accordance with depth and distance and, consequently, that the painting shows a perfect welstand47 and appropriate qualities when seen from a distance. Thus putting in the second paint layer is made much easier.48

When it comes to “putting in the second layer,” Lairesse emphasizes the advantage of having the dead coloring executed properly beforehand. This enables the artist to devote his full attention to the next stage of painting. Here his technique is to start with the background and then to work toward the foreground: “In this phase the best method is to begin at the background, . . . the sky, working forward from there. This will always leave a suitably moist background behind the figures, which offers a chance to fuse their contours with the background.”49

The artist evidently worked in a wet lower layer. In Bacchus and Ariadne it is discernible that the brushstrokes were laid in and spread smoothly in a wet paint layer.

Once the right houding, color, and wyking50 of the images had been achieved, all that remained was to add the extreme highlights and shadows:

The right method is to brighten your painting with a good, thin varnish, mixed with a little viscous white oil, either completely or partly but no more than you can handle before the varnish gets dry; this will bring out the colors. Then add your highlights to the lighted parts, brushing them out softly and thinly.51

What Lairesse describes in the above quotations corresponds closely to his own practice,52 which, it should be added, was highly conventional at the time. He used this practice to achieve the desired artistic effects, given that houding, welstand, and wyking are all crucial to the suggestion of pictorial depth. It is through these elements that he creates the desired pictorial results.53

Flesh Colors

Lairesse dwells at length on the painting of human skin.54 In total, his book lists nine mixtures for flesh color. There are colors for healthy, sick, and dead nudes, and each of these is differentiated according to whether the person is a child, man, or woman. The color to be used for a healthy man is gloeijend,55 while a healthy woman requires a white hue. The softness of young women called for large amounts of white, while men’s skin needed a little ochre.

The skin of a fair and delicate woman is dead-colored with white and [brownish-red]; for the second layer white and a little vermilion should be used. The same is used for a young man, but with the admixture of a little light ochre for the warm, intense effect.56

The beeld is then enhanced using a thin varnish, blended with a little light ochre, rather more for a man than for a woman.57 This is also the moment at which any essential corrections can be made.

If the naked skin is too light in some parts, glaze it thinly with a varnish that holds a little light ochre, vermilion, brownish-red, lake, or asphalt, depending on the tenderness or strength of the color. Then highlight it with the color you find best.58

The bluish tone, which Lairesse associated with “tenderness” (tederheid), is diffused when the final highlights are executed in the wet paint. This requires using paint into which a large amount of pure smalt has been mixed; Lairesse adds that no white should be blended into it and continues: “Then take a soft fitch to apply this blue paint, brushing it out and scumbling it over the most delicate parts. You will notice that this delicate hue produces a natural color that is different in each case.”59

The flesh color used for Ariadne, in the highlights of the arm, is composed of three paint layers (fig. 15). The dead color is pink and contains a great deal of lead white and vermilion. Over this, a light pink layer of medium has been applied, with more lead white and less vermilion.60 Over the final paint layer another small layer of medium has been applied, followed by a light pink layer like the one below.61 The shadow of Ariadne’s chin is composed of two layers, of which the dead color layer is the same as that of the highlight. The layer applied over this has a grayish color and contains lead white and vermilion, a red lake and black pigment, probably bone black.62 The paint surface in Ariadne’s neck appears slightly damaged. The transition from the dark paint in the shadow of the neck to the white paint of her upper torso is quite abrupt (fig. 16). It seems likely that some retouching was added here, giving the transition a more natural appearance, and that this layer of retouching was lost at a later stage, when varnish was removed.

A bluish light appears to hover over Ariadne’s lower abdomen. Could this relate to the “tenderness” to which Lairesse refers? Here as in the other two sections, we see the pink dead color composed of a large amount of lead white and vermilion, over which is a thin layer of medium followed by an extremely thin layer of vermilion. For the uppermost layer of paint, the artist used a beige paint of lead white, chalk, vermilion, red lake, yellow ochre, calcium phosphate (bone white), and bone black. Finally, a thin layer of lead white, chalk, and smalt was applied.63 Smalt is potassium glass containing cobalt, in which the cobalt ion produces the color; when smalt is mixed with oil it is unstable.64 The low potassium content in the pigment particles in this top paint layer is indicative of discoloration.65 The area of “tenderness” was probably not much bluer than now to begin with, since it was an extremely thin layer and the glass particles were crushed very fine and must therefore have had little color intensity. Furthermore, the “turbid medium effect” also contributes to the blue shimmer.66

The flesh color of Bacchus in the shadow on the arm is composed of three layers. The first dead color layer is light brown and consists of red lake, a red earth pigment, chalk, and lead white (see fig. 15). Over this lies a layer of red lake, chalk, and fine red earth pigment. Finally, Lairesse applied a very light pink layer with black pigment, probably bone black, lead white, and a few particles of red earth pigment.67 The red tinge in Bacchus’s nostril consists of three layers, the bottom one being a thick red layer with red earth pigments, a red lake, and lead white. Over this was added a thin layer of medium with a thick light pink layer with lead white and red earth pigment. Finally, there is a thin red layer with little if any lead white and a few particles of red pigment. This paint layer was applied vigorously in quasinonchalant but highly effective brushstrokes (fig. 17).68

(5) Thin red layer with little or no lead white and some red pigment particles

(4) Light pink layer with lead white and red earth pigment

(3) Red layer with red earth pigment, a red lake and lead white with on top a medium layer

(2) Ground layer with lead white, umber, and chalk

(1) Ground layer with umber, chalk, and red earth pigment [side-by-side viewer]

The flesh color of the highlight on Bacchus’s chest is composed of two layers, both of them light in color. The dead color contains lead white, a tiny quantity of red earth pigments, and bone black. Over this the artist applied a layer that probably contains lead white, a red lake, earth pigments, and chalk.69

The appearance of Bacchus is indeed warmer and more “glowing” than that of his companion; more earth pigment has been used to paint him, as advised in Lairesse’s book. Ariadne’s flesh color is dominated by lead white. It is striking that the dead color in Bacchus’s flesh color differs from one section to the next; it was not laid in in a single color, as in the case of Ariadne. As a result of the variation in color in this initial stage, the shape of his body is more clearly defined. Lairesse does not refer to this distinction—that is, in relation to dead color—between the painting of young men and women.

In almost all sections, the paint consists of the three layers that Lairesse enumerates in his book. In the case of Ariadne’s neck, the third layer appears to be missing as a result of damage. In the other case, the highlight on Bacchus’s chest, the three-layer composition appears to be intact. There was no retouching stage here: perhaps it was not deemed necessary in all parts of the painting.

Atmospheric and Color Perspective

There is considerable contrast in color and tone in and around the two protagonists. They are both bathed in light, and the draperies ripple convincingly. As a ceiling painter, Lairesse had to take account of the atmosphere when depicting the sky or the heavens. Few of his sky scenes have any architecture or other earthly items. They contain clouds, sunbeams, numerous “flying” or hovering figures, and above all a great deal of sky. Linear perspective is ineffective here, and the painter necessarily has recourse to other techniques, such as atmospheric and color perspective. The atmosphere between a viewer and an object some distance away creates visual effects that a painter can use in suggesting space. Objects in the distance are less well defined and have fainter contours than those closer to the viewer. The details within these forms are similarly more blurred and softer. Objects in the distance appear lighter in tone than those of the same color that are closer, and in general, contrasts between light and shade appear less extreme from a distance. All these effects are clearer close to the horizon than they are higher up, since the density of the intervening atmosphere increases closer to the ground. This is because the atmosphere contains more dust particles and moisture close to the earth than higher up, near the ozone layer.70 As were other contemporary artists, such as Van Hoogstraten, Lairesse was well aware of all these visual effects.71 He describes these differences at length, giving practical examples, and was clearly familiar with the subject. “It is evident that close to the earth, the air is coarser and denser. But the higher it ascends, the more it becomes rarefied and transparent.”72

Like atmospheric perspective, color perspective too emphasizes the difference between foreground, middle distance, and background. Classic color theory is based on the observation that warm colors appear to advance while cool ones recede. Light waves with a shorter wavelength, such as blue light, undergo far greater refraction as they move through the atmosphere than those with a long wavelength. In consequence, blue light waves are largely scattered in the atmosphere, making the sky appear blue. The quantity of blue atmosphere increases in proportion to the distance between observer and object. As a result, an object will appear bluer as this distance increases. At the same time, the grayish influence of the moisture and dust particles in the air also influence the perception of color. Together with the blue atmosphere, this effect makes objects in the distance appear grayish-blue. Lairesse’s comments on color perspective include the following advice:

In the art of painting, the colors give life to everything . . . They can make things disappear into thin air and make other things come forward forcefully from their background . . . It is of great importance to notice that objects not just grow smaller with distance, but also lose their color proportionally, becoming more and more grayish. Nature instructs us about this phenomenon.73

By depicting objects in the background with more muted colors, less tonal contrast, and less pronounced dividing lines, Lairesse achieves a convincing suggestion of depth on the flat surface of the painting. This makes the cool highlights in the purple draperies in the left foreground all the more noteworthy (fig. 18). Furthermore, the dark purple shadow of the draperies, the purple-brown clouds, and the brown rocks all display little variation in color, seemingly at odds with the rules of perspective. This is probably attributable to changes in the paint layers as a result of discoloration and darkening.

Lairesse has the following to say about painting purple draperies:

When he74 had to paint the portrait of someone dressed in purple or black, he laid the clothes evenly in a uniform dark purple or unmixed black, without indicating any folds. When he then had to complete the work, he put in the highlights and the deepest shadows only. Thus it was finished expeditiously.75

As Lairesse counsels, the first layer applied for the purple draperies is dead color consisting of bone black and lead white. For the highlights, a purple layer is applied over this, consisting of a purple and a red lake with red ochre and lead white—the upper paint layer. Over this lies a layer of medium, on which is added the highlight in the form of a cool gray layer with particles of a discolored lake, bone black, and lead white.76 The lake in the top layer, which has lost much of its color, was originally a more vivid red or purple, making it warmer in tone.

The shadows of the purple draperies are built up in two layers. The bottom layer consists of lead white, a fine red pigment, and black. Applied over this is a thin layer of medium together with a somewhat thicker layer containing a very fine black pigment, possibly lamp black, a scarlet earth pigment, lead white, and a red lake.77

The purple cloud at upper left is likewise composed of two layers. First the artist applied a gray layer with lead white, a brown earth pigment, and a black pigment—probably bone black. Over this he applied a reddish-gray layer with a fine red earth pigment, lead white, and a brown earth pigment.78 The dark brown rocks at upper right are also composed of two layers: a blackish-red layer below, and over this a red layer with lead white and a scarlet earth pigment.79 It will be noted that the shadows of the draperies, the purple-brown clouds, and the brown rocks on the right are all built up in a very similar way. The minimal difference in composition is scarcely visible in the image. This may be because of some darkening of the layers.80 Since these sections are composed of only two thin paint layers, mixed with relatively little lead white, there is more of a tendency here for the dark bottom layer to shine through.

The effect of depth must originally have been stronger, with the draperies—which initially had a higher red content—coming more to the foreground and with more distinctions, if subtle ones, between the clouds and the rocks.

Skies

It can be inferred from the skies in Bacchus and Ariadne that the painting must have been hung on a wall that was to the left of the window, with the light coming from the right. This is compatible with the play of light on the figures. The painting hung above a wooden mantelpiece in either paneling or a frame that was rounded at top, concealing from sight the unpainted corners of the canvas.81 Mary Stuart’s study had only one wall with neither a window nor a door, which was indeed to the left of the window. There was enough space here to accommodate a mantelpiece and a painting. The symmetrical design of the building’s interior makes it likely that the mantelpiece was in the center of this wall (fig. 19).

For the skies above the clouds, the artist used indigo mixed with lead white, a little chalk, and a tiny amount of vermilion.82 The blue paint was applied directly over the ground in the shape of an arch, leaving the ground uncovered in the corners (fig. 20). In some parts, where the indigo paint was applied more thickly, it is opaque and more vivid. A dark strip is visible along the top and the right half of the arch, which widens toward the bottom. Here, the paint contains relatively more indigo than in the rest of the sky, as well as a little black pigment.83 Lairesse’s intentions here are unclear.

The sky is a little transparent in places, where the blue paint was applied extremely thinly, but otherwise appears to be in good condition. Although this also applies to many other parts of the painting, it is striking with respect to indigo. The discoloration of indigo paint is a common feature of seventeenth-century Dutch oil painting and has led to paintings displaying lighter and less intense blue colors. In many cases, the lower paint layers are no longer completely covered, and the painting is marred by the exposure of a yellowed oil medium.84

The good condition of the indigo paint in the sky of this painting can be attributed in part to the use of coarse particles of lead white and a darker ground.85 The main factor contributing to the stability of this indigo paint, however, is the purity of the pigment.86 Where the layer is thicker, it is also more intense in color, but most of the section is painted quite thinly. Still, it is questionable whether Lairesse applied this technique consciously with the object of increasing the stability of his indigo paint. Indeed, this seems implausible, since the sole reference to indigo in his book relates to its suitability for use in underpainting: “For this priming, no fine and expensive pigments should be used, but common ones, provided they have a great consistency, covering well. Indigo and white should be used for a blue priming.”87

Other than might be expected from his recommendations, Lairesse used indigo paint in Bacchus and Ariadne for the top layer in the sky section. Indeed, he also used it for the top layer in his ceiling paintings in the series.88

Lairesse used two types of blue in his painting—indigo and smalt, both of which have sometimes proved to be unstable pigments. That smalt is likely to undergo discoloration with time was already known in the seventeenth century. Theodore de Mayerne attributed this flaw to the yellowing of the oil.89 In spite of this, Lairesse both recommends and uses smalt in the top layers. He frequently refers to smalt in his book, whereas, as already noted, he mentions indigo just once, in the context of underpainting. Until the mid-seventeenth century, most painters thought indigo unsuitable for oil paintings because of its poor stability; it was mostly used for preparatory layers. Toward the second half of the century, a more positive view of the pigment started to emerge, partly because painters had discovered ways of purifying it, and partly because of new, more advanced painting techniques. Indigo started being used in more prominent parts of the painting, and in the top layers, where it was exposed to light.90

While the virtual disregard for indigo in Lairesse’s treatise is in line with the prevailing practice of painters in the first half of the seventeenth century, his own practice seems rather to be in step with the new developments.91 It is also possible that achieving an enduring color may not always have been the decisive factor in the choice of material.

Layer of Binding Medium

Written sources indicate that it was customary to moisten the dried paint surface in between the successive stages of painting.92 Binding mediums of varying composition were suggested: miscellaneous kinds of varnish, often mixed with a solvent or with linseed, walnut, or poppyseed oil. These thin layers of medium were used to resaturate paint that had become matte and unsaturated after drying, or to prevent the upper paint layers from sinking too much into those below. Another advantage of a layer of binding medium, mentioned in treatises, is that it helps to achieve a smooth surface, making it possible to apply paint at greater speed when using a rapid technique.93 It is much easier to blend paint or glaze on an oiled surface. Some painters worked in the wet intermediate layer, while others preferred to wait until the layer of medium had dried sufficiently. In both cases, treatises advise artists to keep the layer as thin as possible, since a surplus of medium may lead the paint to become discolored. We often see thin layers of medium of this kind in paint cross-sections of seventeenth-century paintings.94

Lairesse too used thin layers of medium between his paint layers. He discusses the subject in his book under the heading “Retouching or Revision.”95 This is the final phase of painting, in which the last paint layers and highlights are applied. It is clear from the paint cross-sections taken from Bacchus and Ariadne that the layers of medium were seldom applied directly to the ground, but rather on and between the paint layers above. In some cases, we even find two in the same section, for instance in areas of flesh color and in garments.96 Such a layer is not found throughout the painting: in other words, it was not applied systematically to the entire surface but quite deliberately in some places and not in others. The layers are extremely thin, measuring only approximately 1 micron in depth.

As described above, the areas of flesh color of Bacchus and Ariadne were built up with the aid of such thin layers of medium. When viewed under ultraviolet radiation, these layers show up in the paint cross-sections, because they are clearly fluorescent (fig. 21). They occur most in the sections with highlights and are not found in areas of shadow. From this it may be inferred that saturation was not in fact the main object, since this is particularly important in dark areas.

(8) Residue of varnish

(7) Indigo with probably lead white and some chalk

(6) Red layer

(5) Thin brown red layer

(4) Dark brown layer with on top a medium layer

(3) Dark red brown layer with on top a medium layer

(2) Ground layer with lead white, umber, and chalk

(1) Ground layer with umber, chalk, and red earth pigment [side-by-side viewer]

Lairesse remarks that layers of medium have another advantage: they prevent the paint from sinking in during drying.

If the naked skin is too light in some parts, glaze it thinly with a varnish that holds a little light ochre, vermilion, brownish-red, red lake, or asphalt, depending on the tenderness or strength of the color. Then highlight it with the color you find best; . . . This method guarantees a good result since the colors will not tarnish when they dry.97

Lairesse’s text largely corresponds to his own working method. Before proceeding to the retouching stage, it was necessary to brighten the painting partially or completely with a good varnish: “Use a thin varnish mixed with a little light ochre to bring out the colors of the figure you want to work on. Then put in your brightest highlights, brushing them out very gently in the wet varnish, just as much as you choose to.”98

This varnish was to be mixed with a viscous white oil. The highlights would be gently blended into this wet layer, along with the areas of “tenderness” in the nude and the yellow in the light reflections. If a nude had been laid in in too light a color, this could be corrected by mixing some light ochre, vermilion, brownish-red, lake, or asphalt into the varnish and by lightly glazing the relevant area. The highlight could then be applied on top of this.

It is not clear precisely what Lairesse means when he refers to a “good varnish, into which a viscous white oil has been mixed.”99 “White” may mean lead white, mixed in to help the varnish dry, in other words to produce a “drying oil.”100 Alternatively, it might refer to the type of oil: a light oil, such as sun-bleached oil, or walnut or poppyseed oil, rather than linseed oil.101 The description of the oil as “viscous” suggests that it is either concentrated or oil washed with water. This latter process extracts albuminous substances from the oil, making it more viscous and giving it a lighter color.102 A resin constituent is possible, given the layer’s fluorescence under ultraviolet radiation, but the oil itself may be fluorescent. Unfortunately, these layers are too thin to subject to analysis.

These thin layers were also found in other parts of the painting. The blue garment of the maenad to the right of Bacchus displays the most heavily layered construction of the entire painting, including two thin layers of medium (fig. 22). Over the ground a dark, reddish-brown layer was first applied, then a thin layer of medium, a dark brown layer followed by another thin layer of medium, then a thin brownish-red layer, a red layer, and finally the blue layer of indigo.103 The reason for this complex paint construction is unclear. The layers under the blue are not related to the adjoining sections—that is, the flesh color of Bacchus, the maenad, and the red drapery. It is possible that Lairesse changed his mind regarding the color of the robe while painting it, seeking to achieve the right balance.

Lairesse probably used the intervening varnish to enhance the visibility of the lower layers and to make it possible to blend his paint into a wet layer, to obtain the smooth brushwork that is so characteristic of his paintings. In addition, he was well aware of the adverse effect of porous lower layers and paint sinking into them and sought to avoid this problem in his work.

Although Lairesse discusses varnish in his book, he does so in the context of the retouching phase rather than that of a final varnish.104 These layers of varnish should therefore not be seen as “varnish” in the sense of a final protective saturating layer that was applied over the entire surface of the painting, but as a part of the construction of the paint layers.105

Thin layers of medium were also found in the ceiling painting for Soestdijk Palace. There, as in Bacchus and Ariadne, Lairesse started with the background and worked forward, leaving relatively few blank spaces to be filled in later. Over the ground he first painted the architectural elements: the balustrade, the column, the caryatid, the vases, and the vault. He left some blank space for the protagonists, but many of the other figures, the angels, drapery, and garments were painted over the architecture.106 It is therefore possible that large parts of the scene were first painted and later partly or entirely overpainted. There is a clear example of this in a paint cross-section from the red draperies. The architecture was painted over the ground, and on top of this a red piece of drapery was painted. This resulted in a construction consisting of five layers of paint and two thin layers of medium. The artist started off by painting a green copper pigment mixed with lead white over the ground. Then came the blackish-blue layer of the balustrade, consisting of a mixture of lead white and black. This was followed by the layers of the red cloak: a transparent paint layer of a purple-red lake; a thin layer of medium; a layer of red lake with vermilion; another thin layer of medium; and finally a layer of vermilion.107 This is the kind of painting technique that one would usually expect to find in paintings of a smaller format. It would not have been surprising for him to employ such a technique at the beginning of his career as a decorative painter of large works of art, having initially been trained in easel painting, but even after years of experience working on a large scale, he evidently saw no advantage in saving paint. Lairesse clearly worked according to a preconceived plan.

Conclusion

This study, with conclusions based on evidence such as paint cross-sections, illuminates the painting technique of Gerard de Lairesse in the Soestdijk series and the manner and extent to which it corresponds to the principles expounded in the Groot Schilderboek.

In his treatise, Lairesse sets out to illustrate the relationship between the practice of painting and the theory he puts forward. He views them as inseparable: theory must guide the choices that a painter makes when practising his art, and conversely, his practice must demonstrate that the theory works. In Lairesse’s view, the ideal art was the representation of lofty subjects. His instructions for iconography are therefore linked to the practice of designing a composition.108 Lairesse considers it essential that a viewer can deduce from decorations the room for which they were intended. The choice of subjects for the Soestdijk paintings were preeminently suited to their intended locations and modified to harmonize with the interior.

The artistic concepts that Lairesse uses in the relevant passages, such as houding, welstand, wyking, gloeijend, and tederheid, refer to effects that he seeks to achieve. The systematic construction that he advises to achieve these effects—dead coloring, the second layer, and finally revision or retouching—prove to have been applied almost throughout the painting studied here. In almost all parts of the flesh color of Bacchus and Ariadne, the paint consists of these three layers. Bacchus does indeed radiate a more gloeijend (warmer) appearance than his companion; Lairesse has used more earth pigment here, as he advises in his book. Ariadne’s flesh color is dominated by lead white. There is a difference in the dead coloring of the flesh color of Bacchus between the shadow and the lighter sections; this was not applied in a single color, as in the case of Ariadne. As a result of the variation in color at this initial stage, the shape of his body is more clearly defined. However, Lairesse does not mention any such distinction in dead coloring between young men and women in his book. He wanted his images to possess as much verisimilitude as possible, with the aim of conveying the moral message more convincingly to viewers.

It is clear from the book, and from some parts of his painting, that Lairesse was well informed about the rules of atmospheric and color perspective. This makes the cool tone and sharp contrast in the purple draperies in the foreground all the more noteworthy. These turned out to be attributable not to any flaw in the artist’s skill but to the discoloration of the uppermost layer of lake. The same applies to the bluish-white sheet on the bed, the smalt in which has become discolored. The deterioration of the paint has had the effect of dulling the original gradations between shade and light, and these sections have lost a certain depth as a result. The purple-brown clouds and the rocks on the right appear darker than was originally intended. The thin, dark layers in these sections contain scarcely any lead white, as a result of which they are less opaque and allow the darker layer below to shimmer through. The effect of depth in the painting must originally have been stronger, with the draperies occupying a more prominent place in the foreground and more, albeit subtle, color distinctions in the clouds and rocks.

The original blue-sky section, painted in indigo, is in good condition. This is striking, since the discoloration of indigo paint is a well-known phenomenon in seventeenth-century Dutch oil paintings and has often led to paintings with light and less intense blue colors. Few if any traces of impurities have been found in the indigo paint used in Bacchus and Ariadne. The greatest factor in its stability was the pigment’s purity. That Lairesse made use of unstable pigments such as indigo and smalt suggests that obtaining an enduring color may not always have been the decisive factor in his choice of material. It is interesting to note that while the comments in Lairesse’s treatise are in line with the prevailing practice of painters in the first half of the seventeenth century, his own practice seems rather to be in step with the new developments.