An introduction to the translation of D. C. Meijer’s article on the Amsterdam civic guard portraits. The article was originally published in five installments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. Following this precedent, JHNA will publish the translations of these chapters in different issues: the first two chapters here and the last three in vol. 6, no.1 (2014).

“Ik kan het niet helpen, maar mij komt de kunsthistoricus, die niet de aandoening kan ondergaan van het historische als zoodanig buiten de kunst om, voor als een koe, die geen zoogdier zou zijn”1 (I cannot help myself, for to me the art historian who feels no affinity with history outside of art is like a cow that does not want to be a mammal).

The above quote by the renowned Dutch historian Johan Huizinga serves to illustrate two possible ways of looking at art historical objects, in our case, Amsterdam civic guard portraits. Some consider these pictures mainly as aesthetic objects whose attraction lies in the fact that they are visually appealing. If treated in this way, civic guard pieces become art objects, which have a historical value only as specific cases within the history of art. Visual appeal is perceived as a quality that is stable over the centuries. Others, however, view civic guard pictures primarily as historical objects that happen to be visually appealing. For them, historical context — patrons, clients, social structures, historical influences on the appearance of the painting and its functioning, and contemporary views — all play a primary role. Artists’ abilities and inspiration form an important part of their scholarship but emphatically only a part.

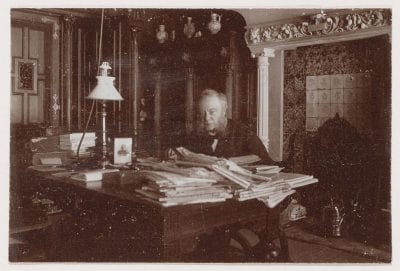

D. C. Meijer Jr. (fig. 1) belonged to the former group. He was primarily a historian, although he received no formal scholarly training (see below). Yet, perhaps surprisingly, in his essays on the civic guard pieces translated here, Meijer showed that he valued the paintings mainly for their aesthetic qualities, especially in the case of the one civic guard piece that, for him, was superior to all the others: Rembrandt’s Nightwatch. Of course, Meijer evinced interest in the captains and lieutenants in the portraits, the great names of the golden age in Amsterdam, but the painters and their work take pride of place. This is visible instantly in the decision Meijer made to order his article into chapters about individual artists.

For modern art historians, the text holds many treasures. Despite Meijer’s verbose style and the lengthy, sometimes exalted critical comments on the paintings, much can be gained from such an old text. It is the first text to treat all the Amsterdam civic guard portraits in a more or less modern art historical way. Surveys by scholars, from Jan van Dyk to Pieter Scheltema, had previously taken the form of descriptive catalogues; their publications provided a list of the paintings with scant additional information. Their biographical data on the artists were often directly copied from Karel van Mander and Arnold Houbraken. Meijer was the first to classify, weigh, and compare.

Yet the historian in Meijer also comes to the fore in the artist biographies. His articles benefited from the great archival endeavors of a generation of art historians that included Nicolaas de Roever, Adrianus Daniel de Vries, and Abraham Bredius. Certainly Meijer’s biographical accounts go well beyond those of Van Mander and Houbraken. The discovery of notes on the Amsterdam civic guard pictures by Gerard Pietersz Schaep was a major find (see below). Meijer’s eagerness to point out the mistakes of the previous generation, most specifically those of Pieter Scheltema, marks his writing as the dawn of a new kind of art history.

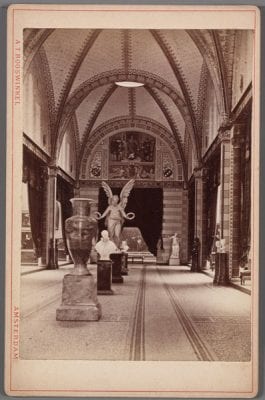

Meijer’s article provides a source for the location of the civic guard portraits and a record of ideas about the paintings at the end of the nineteenth century, around the time of the opening of the Rijksmuseum building in 1885. This was an interesting moment, a pivotal point between two periods of writings about art, first by scholars such as Van Dyk and Scheltema, and later by twentieth-century writers who increasingly sharpened and developed the classifications and comparisons that Meijer and his contemporaries had originally developed.

More than two centuries before, Gerard Pietersz Schaep exhibited little interest in the aesthetic qualities of the paintings. Instead he paid attention to the names of the civic guardsmen, including those of his own family. This is perfectly illustrated by his endearing entry on the Musketeers Civic Guard Hall (Kloveniersdoelen) (no. 30): “An old piece. In which my great-grandfather Jacob Schaap Pietersz is in the foreground. But the painting is becoming unrecognizable because of the flaking.”

Schaep’s notes and Meijer’s article combine to inform us of the changing function of these paintings. They also record the conditions under which the paintings were kept. In Schaep’s time, they were displayed in the buildings for which they were created; in Meijer’s time, the new Rijksmuseum made it possible to house a great part of them in museum surroundings, though other portraits remained in the rooms of various civic officials in the city hall.

Here in this translation, both texts are annotated to give a modern scholarly perspective. With these in hand, we can walk through the civic guard halls alongside Schaep and through the newly opened Rijksmuseum alongside Meijer. It is hoped that this translation will provide renewed historical attention to these important texts, not to mention a good deal of pleasure. Again quoting Huizinga:

What do I enjoy? The art? — Yes, but also something else. It is surely not scholarly enjoyment; really, the history of migrations at the start of the seventeenth century holds no secrets that attract me. “Antiquarian interests are of a lower order,” says the art dogmatist. — Fine. I can only testify that for me this (supposed) inferiority, in comparison to my pleasure in the print as work of art, does not exist. Yes, I’ll go further. It is possible that some historical detail in a print — though it might as well appear in a notary deed, as its source makes no difference — suddenly gives me the feeling of a direct contact with the past, a sensation just as deep as the purest pleasure in art, an almost ecstatic emotion (do not laugh) of no longer being myself, of flowing into the world outside of me, touching the essence of things, seeing Truth through history. Do not think that it is something abnormal, or that I exaggerate the experience: you all recognize it. . . . This is the very nature of what I call the historical sensation. We are now far beyond the confines of art.2

Gerard Pietersz Schaep and His Notes

Gerard Pietersz Schaep (1599–1655) belonged to an old and prominent Amsterdam family. His mother was descended from an equally prominent Dordrecht family, and it was there that he started his career after having studied law in Leiden and Orleans. He married a Dordrecht woman, Jeanne de Visschere. After serving there as an alderman and council member in 1627 and 1628, he returned to Amsterdam, where he held the same functions in 1638. Almost immediately, however, he moved to Middelburg, where he succeeded his father in the Admiralty of Zeeland and remained there until 1647. In that year, he was appointed to the Court of Audits in The Hague, staying in the position until 1649.3 From 1650 until 1653 he served as envoy to England.4 Upon his return to Amsterdam in 1653, he made his tour around the civic guard halls, as he mentioned himself in the heading of the document, “as I have found them, after returning to Amsterdam in February 1653.” The document is kept in one of the four volumes of manuscripts by Schaep in the Amsterdam City Archives, all dealing with the history of Amsterdam.5 The document concerning the civic guard portraits is contained in the volume titled “Schutterijen, ambten, colleges, onderwijs, godshuizen” (civic guards, professions, governing bodies, education, churches). Thus the survey of paintings forms part of a much larger study on the civic guards, which in turn is part of an overview of the history of Amsterdam.

The history Schaep wrote in his notes was hardly a neutral history. From his other writings, most notably the “Antiquarum seu Patriciae Familiarum Aemstelodamensium Catalogus & Progenies,” in which he gives an extensive genealogy of his own ancestors, it becomes apparent that he went to great lengths to prove that his family belonged to the oldest and most eminent of Amsterdam families. He even concocted important ancestors that never existed.6 For Schaep, the history of Amsterdam was a history of families and kinships. For him, walking through the civic guard halls must have been a tour of his ancestors.

Schaep was not the only one to emphasize lineage, as exemplified by Govert Flinck’s Company of Joan Huydecoper. It is hardly accidental that a reference to this painting immediately follows Schaep’s entry: “Ibidem above the door, Jan Huijdekooper the elder, Captain, and . . . painted Ao 1579.”7 The appearance of father and son on two different civic guard pieces in the same hall stressed the role of the family in the history of Amsterdam. This role was emphasized in a poem by Jan Vos, the slip of paper is visible in Flinck’s portrait, in which the young Huydecoper, who served as “peacemaker” in 1648, is juxtaposed with his father, who had earned a prominent role in the early years of the war.8

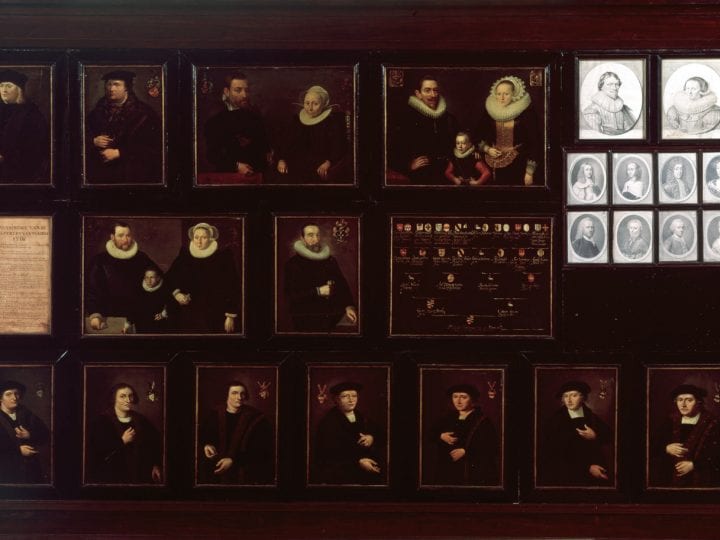

Schaep’s genealogical interests resulted in two peculiar works containing little portraits and pedigrees of his ancestors that are today in the Amsterdam Museum (fig. 2, fig. 3).

D. C. Meijer Jr. and His Article

Dirk Christiaan Meijer Jr. (1839–1908) was a wine merchant who collected prints depicting the history of Amsterdam and was inspired by them to study Amsterdam history more broadly. This resulted in a book, Groei en Bloei der Stad (Amsterdam in de Zeventiende Eeuw I), published in The Hague in 1897. He co-organized the Historische Tentoonstelling (Historical Exhibition) in 1875 and served as a member of the Royal Antiquarian Society (KOG) and the first chair of the historical society Amstelodamum.9 His publications also include De zegepraal der hervorming te Amsterdam (1878).10

As Meijer writes in the introduction to the article translated here, the notes of his friend Adrianus Daniel de Vries (1851–1884) (fig. 4) formed the departure point. De Vries, together with Nicolaas de Roever (1850–1893), founded Oud Holland. Meijer himself also contributed an article on the Amsterdam Doolhof to the first issue.11 In the present article, historian Meijer took an uncharacteristically art historical approach by organizing his text around painters and giving much more attention to their lives than to the lives of the men depicted in the civic guard portraits.

The rediscovery of Schaep’s list was only a first step toward more accurate attributions and descriptions of the collection of civic guard paintings. The discovery in the British Library of a book of sketches (Schaep mentioned this book in his notes) of all the portraits in the Longbow Archers Civic Guard Hall (Handboogsdoelen) gave another boost.12 A whole generation of art historians began publishing articles and catalogues, many of them in the new journal Oud Holland.13 Of course, this sparked some discontent as well. The readers of Meijer’s text would have been struck by the amount of criticism he reserved for Pieter Scheltema (1812–1885) (fig. 5). Scheltema wrote his catalogue Historische beschrijving der schilderijen van het stadhuis te Amsterdambefore the discovery of Schaep’s document.14 He still leaned heavily on the work of Jan van Dyka good century before, but he provided little new information.15 Meijer’s criticism therefore seems quite harsh, but it was possibly provoked by Scheltema’s position as city archivist. Meijer and De Vries had together organized the Historische Tentoonstelling in 1875 and the Amsterdamsch Museum in 1877. This was an endeavor intended to serve as an incentive to the city of Amsterdam to create a permanent museum where, among other pictures, all the civic guard portraits could be shown.16 It would take until 1885 for this dream to become (partly) true in the new Rijksmuseum. Thus Scheltema might well have been viewed as belonging to a civic government deaf to the urging of Meijer and De Vries.

As an overview of Amsterdam civic guard pieces, the text here is, of course, outdated. The heavy emphasis on the seventeenth century in general, and Rembrandt and Van der Helst in particular, makes it quite unbalanced for a modern reader. Furthermore Meijer is verbose (which was quite typical of late nineteenth-century Dutch writing on art). That said, there remains much that is positive in the series of articles. They provide us with an inside view of a time when modern art historical scholarship was still young. Amsterdam had just seen the opening of the Rijksmuseum and all kinds of exciting archival discoveries were being made. By taking Meijer’s essays together with Schaep’s notes (and the catalogues of Van Dijk and Scheltema to which Meijer makes frequent reference) we can understand how the portraits shifted in their function, from historical depictions of groups of men important for the history of Amsterdam, to objects placed in the museum for aesthetic enjoyment, with the Nightwatch positioned as the high altarpiece of Dutch art (fig. 6).

Notes to the Reader

The document by Schaep

For the translation of Schaep’s notes, I have chosen to return to the original manuscript since Scheltema made a number of mistakes in his transcription. In retranscribing and translating I have remained as close to the original document as possible, retaining Schaep’s Greek alphabet numbering for the Longbow Archers and Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Halls, for instance. Moreover, I have provided many of Schaep’s entries on paintings with footnotes citing a selection of later catalogues and current attributions and locations. The inventory numbers link to the online catalogues of (in nearly all cases) the Amsterdam Museum and the Rijksmuseum, where further literature can be easily found.

The article by Meijer

For Meijer’s article (published in five chapters) I have provided annotations that give background information and include corrections. Where Meijer refers to paintings I have followed the same procedure as with the Schaep document. I have retained Meijer’s own notes and marked them as such.