Starting in the 1830’s, city history museums were founded in the Netherlands. Amsterdam was late: the first Amsterdam Historical Museum opened only in 1926. A short lived predecessor was the Amsterdamsch Museum van het Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap (Amsterdam Museumof the Royal Dutch Antiquarian Society)(January – June 1877), founded after the closing of a large scale exhibition on the history of Amsterdam in 1876. The exhibition displayed many works of art and history from the rich collections of the city of Amsterdam. Large parts of these had been given on long term loan to the State, to be placed in the new building for the Rijksmuseum that opened in 1885. The article describes the tensions that arose between those who saw the conservation and presentation of the city’s art and historical collections as a matter of local pride and those whose goal for these objects was placement in a context that furthered national ambitions, namely the Rijksmuseum.

Introduction

In November 1892, the well-known French poet Paul Verlaine traveled to the Netherlands at the invitation of the board of the literary and art magazine De Nieuwe Gids (The New Guide). During his two-week stay, he visited The Hague and Amsterdam, delivered several lectures, and, of course, admired the highlights of the two cities, such as the new Rijksmuseum on the Stadhouderskade, which had opened with much fanfare in July 1885 (fig. 1). Verlaine found the Paintings Gallery impressive, but upon leaving the building he was shocked. Here he encountered the wooden seventeenth-century sculpture group David, Goliath and His Shield-bearer, which originally had come from an Amsterdam maze (fig. 2). Owing to the sheer size of the giant (almost five meters tall), the group was displayed just inside the east entrance, where Goliath’s head practically touched the vaults. Verlaine found the group “slightly mad, not in the right place, it would have been better in the municipal Amsterdam Museum for civic antiquities.”1

The capital city had no such institution. But an observant visitor to the new Rijksmuseum could have imagined how some of the holdings of the new facility might have been at home in a museum of Amsterdam’s art and history. Appropriate examples could be found on the ground floor. In the same space as the remarkable David and Goliath sculpture group (the property of the city of Amsterdam since 1862), the visitor could admire other objects on loan from the municipal collections, such as models of one of the former city gates and of the Amsterdam stock exchange (fig. 3). Moreover, a beautiful collection of arms and armor from the city’s former Wapenkamer (Cabinet of Arms) were also available for viewing at the left side of the Rijksmuseum’s spacious inner court (fig. 4). Another highlight, elsewhere in the ground-floor exhibition rooms, was a showcase with silver and glass objects that had once belonged to the different militia guilds, various municipal organizations, and the city government (fig. 5 and fig. 6). Forming part of the so-called Treasury Room, the showcase was the proud centerpiece of the Nederlandsch Museum van Geschiedenis en Kunst (Netherlands Museum of History and Art), which occupied most of the ground floor of the new Rijksmuseum.2 Until 1887/88, these objects, like several others elsewhere on the ground floor, had formed part of the Rariteiten Kamer (Curiosities Room) and Modellen Kamers (Model Rooms), the museum-like installations in the Town Hall of Amsterdam.

On the top floor, in the Paintings Gallery, over 160 canvases and panels owned by the city, including Rembrandt’s Nightwatch and his Syndics of the Cloth Guild (Staalmeesters), as well as numerous other works depicting civic guards and regents (fig. 7), formed an integral part of the nationalcollections. Moreover, in the Museum Van der Hoop, over 200 paintings belonging to the city were on display in two separate rooms within the Paintings Gallery, most of them from the seventeenth century. These included such famous works as Rembrandt’s Jewish Bride and Vermeer’s Woman Reading a Letter (fig. 8).

In this article, I will address why, at the time of Verlaine’s visit, unlike several other cities in the Netherlands, Amsterdam had not established a municipal museum of art and history. Two official city council agreements lie at the root of this lack, one in 1873, the other in 1880. In these documents, the city council agreed to transfer to the state the greater part of the municipal art collections and an important part of the historical collections. These collections were to be placed on long-term loan to the new Rijksmuseum. But how should these agreements be interpreted? Did the city council envision the Rijksmuseum as a sort of municipal museum of art and history centered on the capital city or did they entertain no such ambition for a museum on the local level?

What seems certain from an examination of the events leading up to the establishment of the new Rijksmuseum, though, is the existence of a certain tension in Amsterdam between local pride in the city’s art, antiquarian, and historical collections and the ambition to give these a national dimension in the Rijksmuseum. The scope of this article does not permit me to develop the subject fully,3 but I do want to exemplify this ambivalence by exploring the fortunes of the Amsterdamsch Museum van het Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap, or K.O.G. (Amsterdam Museumof the Royal Dutch Antiquarian Society), from late January to early June 1877. In many ways, this museum can be considered the forerunner of the Amsterdam Historical Museum that opened in its present location in 1975.4

The Amsterdam Museum Landscape in the Later Nineteenth Century

In order to gain a better understanding of the museological setting in which the Amsterdam Museum of the K.O.G. opened in January 1877, we must understand the character of the city’s museum landscape in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Besides the Museum Fodor, a municipal museum of contemporary (that is, nineteenth-century) art, the city counted three museums that emphasized seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century paintings and prints. These were the Museum Van der Hoop, the oldest municipal museum (opened in 1855), the Rijksmuseum of Paintings, and the Rijksprentenkabinet (National Print Room), the latter two were housed together after 1817 in the Trippenhuis on the Kloveniersburgwal. In the first of these, the Van der Hoop Museum, a high-quality collection of paintings was displayed in two rooms of the former Oudemannenhuis (Old Men’s Home), an early seventeenth-century building. Until 1870, the museum shared premises with the Royal Academy of Arts. Moreover, every three years, a temporary exhibition of contemporary art titled Levende Meesters (Living Masters) was organized in these premises. Other parts of the Oudemannenhuis were used as an annex for the nearby hospital.5 The situation in the Trippenhuis was complicated as well. Here the Rijksmuseum had to share the building with the Royal Academy of Sciences. This led to a continuing lack of space that was irritating to both parties (fig. 9 and fig. 10).6 Since the two museums were within walking distance of each other, many tourists made a combined visit. A few people also visited the nearby Town Hall, which was home to important and interesting municipal collections, including over 130 paintings and many applied-art and historical items.7 Since 1852, the city archivist, who reported to the burgomaster and the aldermen of Amsterdam, had borne responsibility for these collections.8 The large paintings collection, which included many works of high quality, was scattered in halls, galleries, rooms, and little corners of the building, such as the Council Chamber (fig. 11). Several of them hung on the walls of the Cabinet of Curiosities, the Cabinet of Arms, and the Models rooms. Although these rooms were open during special hours for visitors, access to them was difficult (fig. 12 and fig. 13).9

Because of the tight and sometimes even unsafe conditions within both the Trippenhuis and the Town Hall, several initiatives were taken in the 1850s and 1860s to bring the state and city collections together in a new Rijksmuseum, but these endeavors foundered because of the lack of financial resources.10 Owing to shifts in the economy and the political environment, on both the national and local level, chances for serious planning improved in the years 1872–73. On the recommendation of the burgomaster and aldermen, dated June 27, 1873, the Amsterdam city council decided to make land available the next month for the building of a new Rijksmuseum somewhere on the south western outskirts of the city.

Moreover, the city promised a significant financial contribution and guaranteed to make most of the municipal paintings available on loan.11 This was a very important step. Indirectly, it also implied that the city had no interest in founding a municipal museum of Amsterdam history and art. By contrast, Gouda established just such a municipal museum in 1872 based on an extensive historical exhibition celebrating Gouda’s 600th anniversary the same year. The exhibition’s organizers reasoned that it would be regrettable to return all those antiquities, paintings, and historical objects back to the corners in which they had been hidden so long.12

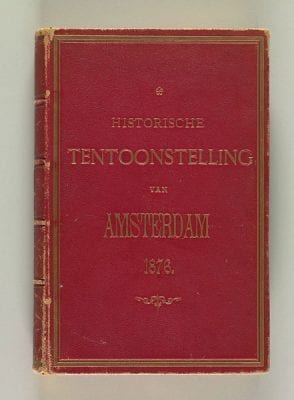

Nevertheless, in Amsterdam, too, pride in the city’s history was hardly lacking. Preparations for a historical exhibition commemorating the city’s 600th anniversary in 1875 generated enormous enthusiasm. A group of fifty-three commissioners, mainly prominent citizens, succeeded in persuading friends, acquaintances, and the city council to lend items from their collections. The result was striking, both quantitatively and qualitatively. For weeks, huge numbers of paintings, furniture, models, fragments of buildings, and many other objects made their way to the Oudemannenhuis, where the organizers engaged in a careful selection of objects.13 Visitors to the exhibition, which was opened in the summer of 1876 and lasted until October 15, could view no less than 4,371 objects loaned from 257 people and organizations, all of which were listed in the catalogue (fig. 14).14 These donors included many private individuals, as well as such municipal entities as the Town Hall and a number of charitable institutions. The Town Hall’s contribution contained numerous paintings, among them Braspenningmaaltijd (Banquet of the Copper Coin) by Cornelis Anthonisz, Koppertjes Maandag (Dam Square with the Lepers’ Parade) by Adriaen van Nieulandt, and a fragment of The Adoration of the Shepherds by Pieter Aertsen (fig. 15, fig. 16, and fig. 17). Terracotta models–preliminary studies for the sculpture groups for the Town Hall on Dam Square by sculptor Artus Quellinus–could also be admired (fig. 18). For the first time, a large audience obtained access to the richness and variety of Amsterdam’s art and cultural-historical collections.

Designed by architect Pierre Cuypers, the History Exhibition had an extraordinary composition and layout. In contrast to earlier exhibitions on antiquities and fine arts in Amsterdam, history now became the focal point, with the objects functioning as illustrations of that story. Art, such as paintings and decorative artworks, formed an integral part of the history (fig. 19). Cuypers also furnished four period rooms–a kitchen, a bedroom, and living rooms from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (fig. 20). Such rooms were completely new for the Netherlands and attracted a lot of international interest as well. 15

The Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap in 1876

This successful exhibition takes us right to the middle of the prehistory of the Amsterdam Museum of the Koninklijk Oudheidkundig Genootschap (hereafter, K.O.G.). As in Gouda, many Amsterdammers found it intolerable to see everything returned to the lenders after the exhibition closed. But, in contrast to Gouda, the Amsterdam municipal government showed no intention of founding a museum of local history–a policy that was, of course, consistent with the obligations granted to the state in the 1873 agreement referred to above. The board of governors of the K.O.G. therefore took an important step toward organizing a museum for which they were fully responsible, the Amsterdam Museum, in the fall of 1876.

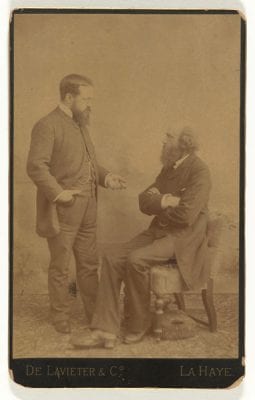

First some background is necessary. The national K.O.G., composed mainly of Amsterdam members, was founded in the capital city in 1858. The mission of the society was to promote and stimulate knowledge and understanding of antiquities on a national and local level. An important means to this end was the establishment of a national Museum van Vaderlandse Oudheden (Museum of Dutch Antiquities), following the example of such new museums abroad as the South Kensington Museum (the present-day Victoria and Albert Museum) in London. To this purpose, right from the beginning the K.O.G. initiated an active acquisition policy, which included obtaining, for example, the renowned Nassau Tunic in 1859 (fig. 21) When it turned out that the K.O.G. could not bring this museum to reality, they displayed and stored their acquisitions in various locations in Amsterdam. Finally, in November 1875, the K.O.G. was able to establish a museum of its own, which made the society’s collection of antiquities and some paintings from cities and regions all over the Netherlands much more publicly accessible. This K.O.G. museum was housed in the former premises of Gerard Heineken’s brewery on the Spuistraat, in the medieval center of the city. Indeed Gerard Heineken played an active and prominent role in the society (fig. 22).16 During the 1860s, the K.O.G. was also involved in the important initiatives undertaken for a new building for the Rijksmuseum mentioned above, where the society hoped to show its collections. Some members of the society’s board even held high positions at the Rijksmuseum.17

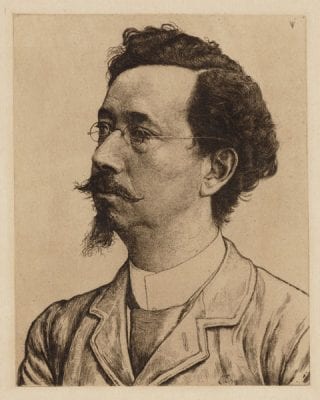

Despite a national orientation at the time of its founding, the K.O.G. began to develop a greater focus on the art and history of Amsterdam from 1876 on. One reason was Victor E. L. de Stuers’s establishment, the year before,of the Netherlands Museum of History and Artin The Hague, an institution intended to function as a national museum of antiquities and historical objects–the very same mission as that of the K.O.G..18 Quite another reason had to do with a decision by the Amsterdam city council. In February and May 1876, the council explicitly assigned the K.O.G. the task of looking after those municipal “antique objects” kept in facilities other than the Amsterdam Town Hall. These included the terracotta models by Quellinus, which had been one of the highlights of the Historical Exhibition (fig. 23).19 For this purpose, the K.O.G. established a special commission on June 12 of the same year, to safeguard the objects of antiquarian value in the city. This commission included the K.O.G. curator Pierre Cuypers and former board member Johann Wilhelm Kaiser, who was director of the Rijksmuseum of Paintings at that time (fig. 24).20

Partly owing to this city council assignment, during a meeting on September 26, 1876, the board of governors of the K.O.G. discussed at length what should happen after the Historical Exhibition in the Oudemannenhuis closed on October 15. The recently established commission, whose members were present as well, stated that it had already written a letter to the burgomaster requesting that as many as possible of the exhibits remain in the galleries. During the same meeting, Cuypers proposed to involve K.O.G. members Dirk Meijer Jr. and Adriaan de Vries in this special project, arguing this was necessary given the huge amount of work that lay ahead.21 A few days later, the board met with these two men in a special meeting, which representatives of the organizing commission of the Historical Exhibition also attended. There they discussed the arrangements for an “Amsterdamsch Museum” in the Oudemannenhuis, fully realizing that such a museum could not, alas, stay there for an indefinite period. The space was needed in the summer of 1877 for the triennial Levende Meesters exhibition.22

Real progress had thus been made during the fall of 1876. Dirk Meijer Jr. and Adriaan de Vries now constituted a special commission for the organization of the new museum. Wine merchant Meijer, an enthusiastic and well-known amateur collector of prints and drawings of Amsterdam, and the young Adriaan de Vries, just named deputy director of the Rijksprentenkabinet, were the perfect appointees (fig. 25 and fig. 26). Moreover, both had also been closely involved in the Historical Exhibition. So much enthusiasm ensued that on several occasions Meijer even proposed to set up a special Amsterdam section of the K.O.G..23

On January 22, 1877, the Amsterdam Museum of the Royal Dutch Antiquarian Society (K.O.G.) was opened in the Oudemannenhuis as a sort of follow-up to the Historical Exhibition (fig. 27). It numbered 890 objects on loan from numerous private individuals, the city of Amsterdam, and various municipal institutions. The city and these other institutions contributed 146 paintings, as well as antiquarian and historical objects, especially destined for sections on the city’s militia, charitable institutions, and guilds. The first section contained 24 group portraits, as well as beautiful silver drinking horns, scepters, and chains that had belongedto the three militia associations. The section on the surgeons’ guilds contained seven anatomical group portraits, among which Cornelis Troost’s Anatomical Lesson of Professor W. Roëll must have made quite an impression (fig. 28).24 Many of these objects had formed part of the Historical Exhibition of 1876, but not all, for the city government had been very willing to give an extra special loan to the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum. It is interesting to note that among the most generous private lenders could be counted several from the K.O.G., such as board members Meijer and de Vries.25 The reviews in the newspapers were full of praise and enthusiasm. In his speech during the opening ceremonies, a representative of the burgomaster and aldermen expressed pleasure at the city council’s involvement in the museum. But he also expressed the hope that the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum would soon move to the grand, new Rijksmuseum.26

Uncertainty Caused by the Slow Progress of the New Rijksmuseum

At this point, it is important to address the new Rijksmuseum, in particular its planning process. Serious agreements had been drawn up in 1873; we have seen what Amsterdam decided in that year regarding the city’s painting collections. But, as with many big projects today, everything went slower than expected and progress and intentions were not always clear. When initial plans for the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum appeared at the end of September 1876, the first piling for the new Rijksmuseum had not yet been driven. Architect Pierre Cuypers had only received the official building order for the Rijksmuseum in May of that same year. Moreover, not until the summer of 1880 was it clear which Amsterdam collections, apart from the municipal paintings already offered on loan in the agreement of 1873, would actually be housed in the new museum. This was true for the antiquarian and historical objects of the Cabinet of Curiosities, the Model Rooms, and the Cabinet of Arms in the Town Hall, and also for the paintings in the Museum Van der Hoop that were not included in the 1873 agreement. The first discussions about including these collections as well in the new Rijksmuseum started only in the early spring of 1878. Not until November 11, 1880, did the state and the city of Amsterdam officially establish the details of these loans.27

It is therefore not surprising that many art-loving Amsterdam citizens expressed uncertainty, both about the completion date for the new museum building and about the composition of its collections, that is, which objects would be coming from the city of Amsterdam (fig. 29). Who knows, they said, might some of the many art treasures and antiquarian objects in Amsterdam be lost before the new Rijksmuseum even opened? Foreigners such as Lord Ronald Gower, an English traveler who visited Amsterdam in 1875, also articulated that concern. During his tour of the collections in the Town Hall, Gower expressed his utter surprise that the city allowed beautiful paintings by Ferdinand Bol and Van der Helst to be hidden away in badly lit office spaces where they could barely be admired. “No nation but the Dutch or English would allow these two works to remain in their present situation…Amsterdam is promised a gallery worthy of its pictorial treasures, but at present there are no signs of this much-to-be-wished idea being carried out.”28

With this uncertainty in mind, we can track the organization and composition of the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum. Several passages in the foreword of the catalogue published by the museum illustrate this anxiety (fig. 30). Authors Meijer and De Vries revealed their dismay that in 1876 the city had not also given the K.O.G. responsibility for caring for the objects in the Town Hall, which, in their opinion, were so obscurely displayed. This included the paintings. There are still “a far greater number of masterpieces in the corridors, landings, upper rooms and attics of the Town Hall than can be admired in the Oudemannenhuis. . . . Just bringing various things together would be enough to provide the state capital with a municipal museum that would surpass all such establishments in our country and include art treasures, which would arouse the jealousy of the greatest foreign museums.”29 They called on city council members to avoid waiting until the Rijksmuseum opened its doors. Too much would be lost with such a wait. Unfortunately, the number of visitors to the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum failed to meet expectations and the K.O.G. faced an operating deficit of more than a thousand guilders. The city council refused to help and demanded the return of the objects on loan by July 1, as had previously been agreed.

Deliberations and Irritations

In an exchange of letters between the board of the K.O.G. and the burgomaster and aldermen in the period May 2 to June 20, 1877, the society put up a determined fight to exhibit, after the closure of the Amsterdam Museum, some of the material in the galleries of the Oudemannenhuis, at least the collection of paintings from the Town Hall and other Amsterdam municipal institutions (fig. 31). The chairman, H. J. van Lennep, was responsible, first of all, for this proposal; he also happened to be a member of the Amsterdam city council. Adriaan de Vries supported this idea, too, and soon became the driving force behind it.30 Moreover, other members of the K.O.G. board of governors started to argue strongly that works of antiquarian value and historical objects, such as those from the Curiosities Room should be included in such an exhibition (fig. 32).31 Frederik Muller, a well-known Amsterdam bookseller, antiquarian, and collector of historical prints, and a previous chairman of the society, proposed such a selection in the board meeting of May 19, 1877. He argued that the Cabinet of Curiosities in the Town Hall was almost inaccessible and that it was impossible to present all objects in a good way. As the minutes record: “now is the time to convince the city council that Amsterdam should establish its own museum; he indicates that he does not propose this in the interest of the K.O.G. but only in the interest of the city.”32

The burgomaster and aldermen’s letter of June 4 reacted to this proposal negatively. They argued that the paintings would be better displayed in a new wing of the Town Hall and that the objects from the Cabinet of Curiosities and the Model Rooms should be returned from the Oudemannenhuis to their regular place in the Town Hall. An emergency board meeting discussed this response two days later, amid a heated atmosphere. In the meeting, Adriaan de Vries articulated his dismay and stated his intention to express this in the newspapers.33 The outcome of the intense discussion was recorded in a letter dated June 20, just before the closing of the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum. This letter served as a final attempt to convince the city government that the well-being of the city’s collections was at stake. The K.O.G. emphasized that even though the paintings would be better placed in the new wing, the Town Hall was still not easily accessible, and therefore not the place “where one of the richest collections of masterpieces of the Old Dutch school of painting belongs.”34 The board suggested following the example of Haarlem, Leiden, Alkmaar, and many other cities, where treasures in the public domain had been made accessible to the citizenry. It made no difference. The burgomaster and aldermen adhered to their previous statements.

The developments described above demonstrate the heightened emotions generated by issues of preservation and accessibility of the art and historical heritage of the city of Amsterdam. In some ways, this differed little from discussions leading to the creation of local art and history museums in other Dutch cities at the time. By 1877, cities such as Utrecht, Middelburg, Dordrecht, Haarlem, The Hague, Leiden, Alkmaar, and Nijmegen could already count city museums of art, antiquities, and historical objects. The first was established 1838, and most originated between the 1860s and 1870s. These were often initiated by antiquarian societies, but sometimes by members of the municipal government or even individuals. Some cities started a local museum later, as was the case in Delft in 1897. Local pride was a strong motivation, sometimes combined with a flavor of nationalism. Utrecht possessed the seat of the Catholic bishops, Nijmegen was proud of its Roman past, Dordrecht claimed to have the oldest city rights (stadsrechten) in Holland, and The Hague asserted its distinction as residence of the stadholders and as seat of the national government.35

In the case of Amsterdam, feelings of local pride and national ambitions arose from its history as the most powerful city of the republic, and of course its status as capital city. As with the other cities just mentioned, Amsterdam had experienced a growing feeling of pride in the splendor and richness of the municipal art and historical collections, so beautifully displayed during the Historical Exhibition of 1876 and in the K.O.G.’s Amsterdam Museum. At the same time, worries about the conditions under which these collections were shown and preserved grew stronger as did worries about limited accessibility.

What made Amsterdam’s situation different from that in other cities was the way ideas about preservation and presentation, especially of the paintings collection, were influenced by the various plans for the Rijksmuseum of Paintings. While Gouda, for example, had established its local history museum with the cooperation of the city government, in Amsterdam, such a step became very difficult, because of the city council’s official agreements with the state in 1873 and 1880.

An Amsterdam Gallery in the New Rijksmuseum?

The disputes between the K.O.G. and the burgomaster and aldermen of Amsterdam quieted down during the fall of 1877. The burgomaster and aldermen were in some way giving in to the constant pressure from the K.O.G. The city officials probably took the view that they were hardly neglecting their responsibilities: under their supervision, the city archivist, Pieter Scheltema, functioned well as keeper of municipal collections. Ever since 1852 he had been taking his job very seriously, writing catalogues of the collections, making several acquisitions, and trying to improve the condition of the paintings and objects with the help of specialized restorers.36 But improvement was possible, certainly in the case of the conservation and presentation of the paintings collections. As a result of the pressure exerted by the K.O.G., the city council decided that fall to install a new Committee of Supervision and Advice for all municipal paintings. The K.O.G. was well represented on this committee.37

However, for some K.O.G. board members the idea of a special presentation of Amsterdam’s art and history had became more and more attractive. Therefore, discussions within the K.O.G. on this topic continued, but took a different direction. Attention shifted away from the Oudemannenhuis; the idea was now to create a separate Amsterdam gallery within the new Rijksmuseum. This became clear during a board meeting on April 16, 1878, when discussions were held for the first time with Pierre Cuypers in his function as Rijksmuseum architect. They focused on the exhibition areas for the K.O.G. in the new Rijksmuseum. Besides considering their own collections, which were to be placed on loan in the Rijksmuseum, some board members indicated their hope for a gallery in the Rijksmuseum devoted to objects exclusively connected with the city of Amsterdam.38 This came up again on June 10, 1880. In the loan agreement with the state concerning the society’s own collections, the chairman remarked that he wanted to stress the importance of such a separate Amsterdam gallery. He added that the burgomaster had reacted rather positively to the idea during a recent conversation, partly because this could become an opportunity to exhibit objects from the Curiosities Room of the Town Hall. The reaction of Cuypers, at the time both a K.O.G. curator and the architect of the new Rijksmuseum, is quite straightforward: the state offered the K.O.G., at no cost whatsoever, a room to present its collections. It was therefore imprudent to ask for a museum within the museum.39 This discussion was more or less repeated in September of the same year. Board member Adriaan de Vries in particular argued strongly in favor of such a gallery in the Rijksmuseum and also for the artworks and antiquarian objects in the Town Hall to be made available.40 De Vries continued to hope for this outcome during the following years.

The question of an Amsterdam gallery in the new Rijksmuseum became a detailed agenda point one last time on December 15,1884. During a long and difficult meeting of the board, attended by the influential senior government officer for culture, Victor de Stuers, and the new director of the Rijksmuseum, Frederik Obreen, time was running out and all differences had to be resolved (fig. 33). Early in the meeting, De Stuers spoke in memory of Adriaan de Vries, who had died the same year. He was the one who, in the words of De Stuers, had so strongly insisted on a special Amsterdam gallery in the Rijksmuseum. After some deliberations, during which the chairman of the K.O.G. once more repeated the idea of bringing together in this gallery everything connected to the city of Amsterdam, they concluded this was impossible: it would never fit. As a concession to the society’s wishes, De Stuers suggested displaying remarkable Amsterdam plans and cityscapes. But this was rejected on the grounds that it was unwise to exhibit in such close proximity to the Rembrandt gallery a collection of totally different quality and size.41

Seven months later, the new Rijksmuseum opened with over three hundred paintings on loan from the city of Amsterdam. An Amsterdam gallery had not been realized, a Rembrandt gallery had. The establishment of a Rembrandt gallery was applauded. But for the rest, this was hardly what the proponents of a separate presentation on Amsterdam art and history had hoped for.

Epilogue

And Goliath the giant? Only in the course of 1887 and 1888 did the many objects from the Cabinet of Curiosities, the Cabinet of Arms, and the Model Rooms–including the sculpture group David, Goliath, and His Shield Bearer–move to the new Rijksmuseum. They were displayed, as indicated earlier, on the ground floor, together with objects from the Netherlands Museum of History and Art. In the years 1886 to 1888, Nicolaes de Roever, archivist and then curator of these municipal collections, dedicated three articles in the periodical Oud Holland to keeping alive the memory of the Town Hall exhibition rooms (fig. 34). De Roever expressed no regrets over the disappearance of the Town Hall’s “Cabinet of Curiosities, the first Museum of Antiquities…because it never promised to become the core of a great historical Museum about the trade city which once ruled the commercial world.” More was achieved, he wrote, by the establishment of the Netherlands Museum of History and Art in Amsterdam, which offered the history of the fatherland over that of a local history. Nevertheless, he remarked “with that the door was closed inevitably for small local items, which would certainly have found a much larger place in an Amsterdam Museum.”42

In 1895, Amsterdam did open the Stedelijk Museum. During the first years of its existence this was home to a somewhat strange variety of art and historical collections. The museum devoted some rooms to the history of the city, exhibiting several remaining historical and antiquarian objects from the archives of the Town Hall. Yet even that display disappeared several decades later. Already around 1914, the director of the Stedelijk Museum decided to remove these objects from the museum in order to concentrate on modern art. In 1926, the objects went to the new Amsterdam Historical Museum, a museum established the same year in De Waag, a former weigh house, right in the center of the city.43

The next and concluding step occurred in 1975, with the establishment of a large historical museum (successor to the museum in De Waag) that opened its doors to the public in the former city orphanage on the Kalverstraat, just where it is today. In the large permanent exhibition on the history of Amsterdam, visitors could admire paintings and objects that had been on long-term loan to the Rijksmuseum since 1885. Although the negotiations had been protracted and the Rijksmuseum’s relinquishing of certain works sometimes difficult, a large and impressive Amsterdam history museum had finally come into being, with the Goliath sculpture group as the big attraction for the museum’s restaurant visitors.44