The first installment of D.C.Meijer Jr.’s “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Portraits within and outside the new Rijksmuseum.”

Almost one-and-a-half years ago, we stood at the grave of A. D. de Vries Az.,1 the tireless fighter for truth and beauty, the scholarly friend of the arts, for whom a lie was a horror, in whichever form or for whatever goal. His incorruptible diligence, alongside his exceptional memory and his sharp analytic skills, made him an art historian of the first rank. Whenever these extraordinary gifts were employed together with his restless diligence and enduring patience, made this son of one of Amsterdam’s most influential art-loving families easily triumph over all kinds of small difficulties. Although such difficulties often bar the way for others, one could justly expect something big of him in the field that was his natural terrain. But alas! It was not meant for him to reap the fruits of his labor. The artist who translates the inspiration of his genius to paper or panel in an instant can have done enough for the development of humanity and his own fame in the course of a thirty-three-year life — the patient scholar, who sets the task of finding and arranging building materials often leaves incomplete work that honors his memory when his life is cut short.

And that was certainly the case with Adriaan de Vries, whose exceptional meticulousness prevented him from publishing the results of his studies before he was sure nothing remained to search for or discover about his subject.

First among the many things he had set as his lifework, which proved impossible to accomplish, was the cataloguing and analysis of the Amsterdam civic guard portraits. The passionate love he felt for his native city would have been enough for him to find the work appealing. In addition, the high value that the pieces have for art and art history equally increased his enthusiasm, while the disgraceful neglect and hopeless confusion of the collection aroused his pity and indignation. With courage and good spirits he set himself to work when the Historical Exhibition of Amsterdam in 1876 raised hopes that an era of general appreciation of the art treasures of the city would dawn.2 The temporary exhibition of the “Amsterdamsch Museum,” as a department of the Royal Antiquarian Society, scheduled the next year in the Oude Mannenhuis, was a first result of that revival. During the production of the catalogue for the Amsterdamsch Museum (work that for me is connected with the most pleasant memories of intense yet pleasant cooperation with Adriaan de Vries) we still had hopes of putting together a chronological list of all the civic guard portraits. Along with other illusions, as the foreword of the catalogue testifies, that hope went up in smoke. All our research brought no other result then this: the account we envisioned was impossible so long as all the portraits could not be exhibited together in one gallery for study and comparison. We had to give up.3

In the meantime, the civic guard pieces that had been shown in the Amsterdamsch Museum exhibition were stored again with their counterparts “in hallways, porches, upstairs chambers and the attics of the city hall.”4 Yet throughout the desperate struggle over the paintings that Adriaan de Vries had mounted against the city’s slowness and indifference, he never lost sight of work on the catalogue. Again he was provoked by the appearance in 1879 of the Historische beschrijving der Schilderijen van het Stadhuis [Historical description of the paintings from the city hall], by the archivist P. Scheltema, whose work, from De Vries’s point of view, was nearly the model of what a catalogue should not be.5 To devise something better, and completely different, naturally remained his goal. For the time being, however, there was no possibility of that.

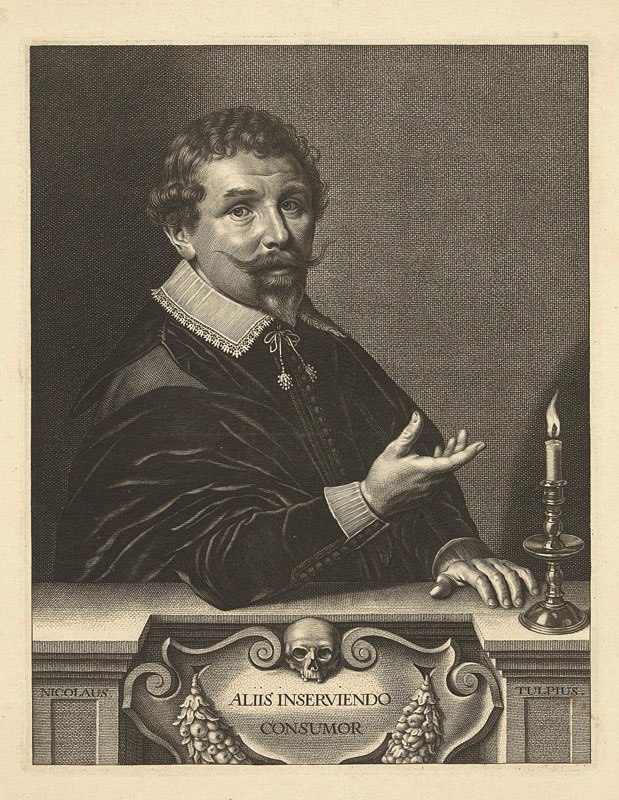

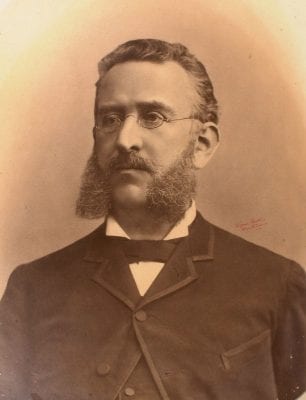

New encouragement arose, however, with the discovery of the manuscript by Gerard Schaep, which contained, among other important notes regarding the civic guards, a remarkable list of the paintings present in 1653 in the three Amsterdam civic guard halls. Recognizing the importance of the document for Amsterdam, Mr. Ger. A. Heineken [fig. 1],6 who had owned it for some time, showed it to De Vries. With the same selflessness that inclined him later to donate the document to the City Archives, Heineken lent it to De Vries for his work. Extraordinarily happy, De Vries rushed home with his valuable treasure, after making a careful copy of the whole list of seven folio pages before moving them into the archives. With a certain excess of caution that was a trait of De Vries at the end of his life (caused by bitter experiences with those who sometimes succeeded in eliciting the results of his studies from the naturally guileless and open young man, he only spoke in general terms of the manuscript and the interest it could have for him, so that it raised expectations higher than the results would be able to satisfy. Schaep’s list, which had aroused the curiosity of so many, has recently been published (1885, by Ten Brink and De Vries) in the seventh volume of Aemstels Oudheid by the now late P. Scheltema, archivist of Amsterdam.7 Now everyone can judge how much or how little art history has gained from the discovery of this document. Such annotations as “A piece above the door,” “Ibidem before the chimney,” “Ibid. another old piece” are certainly of little use! Yet the list holds so many indications of years and names of painters and persons portrayed that one would superficially think that with the paintings at hand one could make a fully satisfying catalogue. Nothing could be less true, because the majority of the portraits lack markers by which to identify them. Apart from a few exceptions, the facial features of the captains and lieutenants that Schaep mentions are not known to us, and the dating and monograms he found on the paintings are often gone. For example, when one reads “Captain Arent ten Grootenhuijs. lieutenant Nanning Florisz. Cloeck. Painted by Frans Barentsz. Ao 1618,” [fig. 2]8 one gladly discovers that among the Amsterdam civic guard pieces, a painting with a certain date can be found, from an, until now, unknown master. But standing in front of half a dozen paintings that all might well have been painted in 1618 and of which there is none that can be proven not to be the piece by Barentsz, then one comes to the tortured awareness that information is lacking for identifying the portrait for which one searches.

I am no stranger to the thought that the encounter with this problem, in addition to his research in the Netherlands and abroad on the history of the most important Amsterdam civic guard piece, the one by Rembrandt, has been the reason why it took De Vries so long to publish his results.

Whatever the reason for this, De Vries was taken from us before we were able to read something by his hand on the discoveries generated by Schaep’s document. When his literary legacy was divided, De Vries’s family trusted me with the honorable task of editing and publishing the notes he left concerning the civic guard portraits. I accepted that task with great pleasure because there was no subject, among the many that De Vries studied, that could interest me more than this. It is also a subject on which I had cooperated with him for so many hours and on which we had exchanged views so frequently.

The execution of that task would, however, have acknowledged its importance completely differently, if the unforeseen death of my deeply mourned friend had not been preceded by a lack of necessary preparations. Had De Vries been an old man, with one foot in the grave, I would not have let him work alone without keeping me up to date; but even an old man might have been expected to write down all kinds of remarks that he kept only in his head. Those remarks thus went with him to his grave. Although De Vries was known for the many notes he made, he had this in common with many others: he only wrote down what he could not risk forgetting and could not see again at a later moment. That is the reason why many will search in vain in these pages for this or that which he thought De Vries knew — and I do not claim that he did not know it at all, but I could not present it here because he never told me when he was living, and I did not find it after his death, despite the precision with which Misters De Roever and Gebhard9 sent me every piece of paper that might concern the subject.

Despite the disappointments that I, too, regretted, and which I must now share with my readers, there remained enough to instill great interest in all friends of Dutch painting, and worthy of celebration, in the journal [Oud Holland] that the deceased co-founded, a tremendous feat that he did not live to experience: the opening of the large museum destined to harbor the national art.10

At this moment, only a part of the art treasures I direct to the attention of my readers is present in the Rijksmuseum. I will therefore take the liberty of addressing, for now, only those pieces that have been deemed worthy of a place in the new Rijksmuseum, and in this first article those that have been hung in the Hall of Honor. When I write about the others, I hope everyone will have the opportunity to see them all.

Leaving for later the civic guard portraits that were previously exhibited in the Trippenhuis — the one [Nightwatch] by Rembrandt,11 the meal of civic guardsmen by Van der Helst,12 and the so called joyous feast of civic guards by Flinck,13 I would first like to return to Schaep’s list in order to bring attention to a name that is mentioned frequently but has not become well known until now. Although he [Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy] does not shine on the wall of the [Rijks]museum in golden letters, he is bound to receive European fame by the quality of his works, particularly in that museum.

Claes Elias [Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy]14

It was as if De Vries had a premonition that after his death he would finally assure this excellent artist the place of honor that he deserves, because over and over he made the greatest effort to discover everything about him. His attention was first drawn to [Elias] by his anatomical lesson of Fonteyn15 in the collection of the surgeon´s guild, which had been half destroyed by fire and was later heavily over painted.16 De Vries was also drawn to the letters “N.E.P.” that he found on a portrait attributed to Santvoort, a depiction of governors from the Spinhuis [fig. 3]17 that we had been allowed to keep in the Amsterdamsch Museum of 1877 after the historical exhibition [of 1876], together with Santvoort’s portrait of governesses.18 De Vries also encountered “N.E.P.” on a portrait of Tulp in the collection of Mr. Six [fig. 4],19 easily to be interpreted as “Nicolaes Elias Pinxit.” But if De Vries, now that we have gotten to know Elias better, would still attribute the portrait of the governors to him is something I would not dare to decide so long as [the painting] stays in its prison at the Werkhuis, not to be seen again.20

There had to be an Elias, however, among the civic guard portraits as well; after all, his name was mentioned as the painter of no. 83 (now no. 129) in the Aanwijzing of the city’s paintings by Scheltema (1864).21 Furthermore, Jan van Dyk’s Historische beschrijving van de Schilderijen van het Stadhuis (1758), a book to which we will refer many more times, mentioned a work by “N. Elias” “painted 1639” as well.22 According to Van Dyk, this portrait contained the names of the men portrayed “on a note as if inserted between the frame and the painting.” Van Dyk even wrote down the names: “D.E. Capitein Dirk Tyenburg, Pieter Adriaensen Raep, lieutenant. . . ,.”etc. But a portrait with such a note was not to be found among the collections of the City Hall. And concerning the painting no. 83, along with which the city archivist had printed the name of Elias — however dark it might have been in the “hallway at the cadastre,” where this piece had been hung23— one single look was enough to reveal that this was not a painting from 1639. How then did Mr. Scheltema come to the opinion that this was the painting by Elias that Van Dyk mentioned? His methods were very simple. With most of the paintings, Van Dyk reported the number of persons, in this case: twenty-three. One therefore counts the number of civic guards and there it is. Mr. Scheltema looked among the “fifteen old paintings, of which one is made in 1588 and one ditto 1623,” which were thus described in the old Beschrijving der schilderijen printed by the Stads-Drukkerij in 1841, for the piece that depicted twenty-three persons and catalogued this as by N. Elias. C’est simple comme mentir! [That is simply the same as lying!]. Those who have known A. D. de Vries can imagine how he lashed out at this. Glowing with outrage, he wrote a letter in which he summoned the poor Scheltema to bring forth the real Elias that had been there after all. But Mr. Scheltema simply had no idea where it was and could give no other satisfaction. In the second edition of his Aanwijzing (published in 1879 under the title Hist.Beschrijving),24 he thus omitted [connecting] the name of Elias with painting no. 83 (which by then had become 129).

Luckily we can present a better clue. Lieutenant Pieter Raep, the treasurer who built the Raepenhofje25 — “out of compassion here [in Amsterdam]” — had remained a popular figure among the city’s population because of Amsterdammers’ fondness for almshouses. Thanks to this, perhaps more than anything else, [Raep’s] portrait was etched by Houbraken in the previous century after the civic guard portrait in which he is depicted. In Houbraken’s etching one reads: N. Elias pinxit [fig. 5].26 This portrait can be located in no. 122 (formerly 41), which hung until recently in the office of the chief clerk of the financial department in City Hall [fig. 6].27 Houbraken further noted that the portrait after which he made his engraving, hung in the (then) City Hall in the room of the “Schepenen extraordinaris,” which accorded with Van Dyk’s statement. There is thus no doubt that the painting depicting Raep is the Elias portrait that Van Dyk mentions, although presently (and this is the reason why it remained unknown for so many years) it does not portray twenty-three, but only twelve men. This should not surprise anyone; it is not the only Amsterdam civic guard portrait that has been mutilated. A part of the painting had probably suffered [damage]; that part must have been cut off and unfortunately it was precisely that part which included the note and the names of the persons (and probably also Elias’s signature). Schaep described it thus (Kloveniersdoelen No. 9): “In the front house, following the previous. Dirck Theulingh captain and Adriaan Pietersz Raep. lieutenant done Ao 1639 by Claes Elias.” Date and painter therefore correspond with what in the days of Van Dyk and Houbraken was still visible on the painting. Schaep made an error with Raep’s first name, however, and that teaches us to use his notes carefully. He and not Van Dyk was mistaken. That much is evident from a list of officers of the civic guard companies that Schaep gave elsewhere in his document. It makes clear that Pieter Adriaensz Raep, and not his father Adriaen Pietersz Raep, was Lieutenant in district 20 (he would later even become the captain of that district), first serving under Captain Pieter Bas, and after 1632 under Captain Dirck Theulincx. In regard to the latter’s last name, Van Dyk was [the one] to make the error; he read Tyenburg instead of Theulincx, the name that Wagenaar then copied after him.28

The other portraits that Schaep mentioned as works by Claes Elias are:

(Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Hall [Voetboogsdoelen] no. 2) Captain Jacob Rogh and Antonie de Lange, lieutenant, Ao. 1645.29

(Id. 12) Captain Mathijs Willemsz. Raephorst and Lieutenant Hendric Lourisz Ao….30

(Id. 13) Captain Jacob Backer and Jacob Rogh, lieutenant, Ao 16.31

That last portrait had been admired by De Vries many times, but he never knew Elias had painted it. That piece is in fact the beautifully painted meal (formerly no. 64, new no. 75) that has been transferred from the office of the chief clerk for public works [publieke werken] to the new [Rijks]museum and nowadays has acquired a place in the “holy of holies,” the Rembrandt room (to the left of and above the picture by Thomas de Keyser) [fig. 7]

When this painting was shown in the Amsterdamsch Museum in 1877 (no. 235), we were pleasantly surprised to find in the main character, holding the napkin in his hand, the portrait of Burgomaster Backer,32which had been exhibited by his descendant Mr. C. H. Backer, Esq. at the Historical Exhibition of 1876 (no. 331) [fig. 8].33We could therefore rename this portrait as the meal of Backer, although we did not yet know who had painted it. Schaep’s notes affirm this now without any doubt, because no other civic guard portrait on his list mentions Backer’s name. It is now also possible to determine the approximate year. Roch became Backer’s lieutenant in 1627 (in district 9) and they remained together, surely until 1630,34 but in all probability until February 1632, when, following tradition, Backer became burgomaster and resigned from his captaincy.35 Roch succeeded him as captain, and it is not unlikely that it is a farewell meal that has been recorded on this canvas, offered by the captain to his most important civic guards in the Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Hall, to which district 9 was connected. In any case, the painting was not executed before 1627 nor after 1632.

Scheltema’s Historische beschrijving mentions it as being by Paulus Moreelse.36 Scheltema considered it the portrait with twenty-four civic guardsmen that, together with the first described, hung in the office of the “Schepenen extra-ordinaris.” Van Dyk noted of this same picture that he found no name, date, or mark, and considered it a work by Paulus Moreelse. Van Dijk attributed to Moreelse quite a lot of what he could not identify, but found attractive, if it was from the first third of the seventeenth century; but from what he added, it appears that he did not really know what to do with the time in which it is painted. Wagenaar, who in other cases faithfully copied Van Dyk, was more cautious: “We do not know who painted it.”37 On another note, Scheltema was probably right about his no. 75 — our meal here; he identified it with the painting that [resided] with the “Schepen extra-ordinaris” (Van Dyk’s no. 104).

I now bring attention to Lieutenant Jacob Roch, who is next to the captain by the well-filled dish. After he became captain himself, he appointed Egbert Boom, Dirk de Graeff, and Roelof Bicker as his lieutenants; the next in that function was the wine merchant Anthony de Lange, the son-in-law of the “gray-haired” Burgomaster Harmen Gijsbertsz van de Poll, to whom Vondel sang his beautiful ode on the inauguration of the Athenaeum Illustre.38 Roch had himself depicted by Elias again with this new lieutenant [de Lange] in 1645, as Schaep notes.39 In order to identify him in a masterpiece executed then, we have to commit to memory the figure of Jacob Roch, which is not difficult because of his girth and his unusual physiognomy.

We therefore have to return to the second section of the Hall of Honor where we see him [Roch] walking between his civic guardsmen, somewhat grayer, in the exquisitely painted no. 7 (formerly no. 23). It used to hang in the dark in the City Hall meeting room and the name of the artist was lost. We can connect it now with Elias thanks to recognizing our friend Roch. There is another reason why I really can attribute this piece to Elias. The civic guardsmen were divided into the districts in which they lived, and if a certain building is visible in the painting, as the tower of the Oude Kerk is here, then we can assume that the squad facing us is the one from the district around that building. And when that squad had a painter of a certain rank in its midst, it seems obvious that the portrait of the squad was assigned to him. The place where a painter lived is not unimportant for determining the maker of civic guard portraits. Well: “Elyas the painter” was living on the “frouweelen burgwal” (in the seventeenth century the whole east side of the Oudezijds Voorburgwal was called that) when in 1636 one of his children was buried in the Oude Kerk,40 where on December, 27, 1626, he baptized a son (the name of the mother was Lievijntje Bouwens).41 He already lived near the Oude Kerk when in 1625 he bought some items in the inventory of Cornelis van der Voort, and when on March, 24, 1621, he posted his notice of marriage.42 The house was on the corner of the Minnebroerssteeg (nowadays Oudekennissteeg). Later Elias owned a house on the Breestraat past the St. Anthonysluis. This house shared a wall (on the southeast side) with Rembrandt’s house.43

Mr. N. de Roever, who gave me all these notices from notes in the Archives, also found the name of the father of our painter, namely Elias Claesz Pieckenoy, from Antwerp, a weapon cutter (wapensnijder), who posted his notice of marriage in 1586 in Amsterdam with Heyltje ’s Jonge. Another son of this Antwerper, Elias Eliasz, goldsmith, kept the second name Pieckenoy, as becomes clear from his prenuptial agreement with Willemtje Jans (1622), in which his brother, the painter, and his father testify. In 1646 Nicolaes Elias, the painter, was still alive, according to a document that De Vries found, but in 1656 Levine Bouwens was a widow.44

Elias’s district of civic guardsmen was the ninth: it ran from the Damrak to the Geldersekade and from the Heintjehoeksteeg to the Oudekerks-Kerkhof. In 1650, Roch still lived on the Geldersekade, near the Stormsteeg.45

Given its conception and painting style, another portrait is without doubt from the same hand, and here the Jan Roodenpoortstoren plays the same role as the Oudekerkstoren in the previous painting. This is not yet in the [Rijks]museum, for it still hangs in the council hall in the City Hall, on the higher side, with number 4 (formerly 30)46[fig. 9]. I do not hesitate to attribute this to Elias, too; we learn the identification of the company by the Jan Roodenpoortstoren, since it served as a bell tower for district 4.

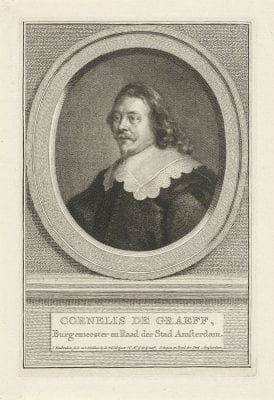

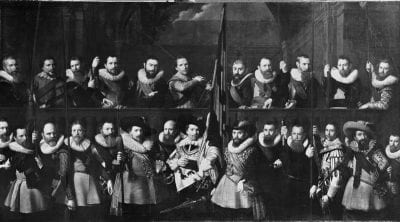

Jan Claesz Vlooswijck served as captain in that district from1628 until at least 1647, and Gerrit Hudde as lieutenant until at least 1636. They had themselves depicted in the best possible company (directly next to the Nightwatch) in the great hall of the Harquebusiers Civic Guard Hall (Kloveniersdoelen), along with the ensigns, both sergeants, and thirteen civic guardsmen. Vlooswijck’s portrait also appeared elsewhere in the hall, in the chimney piece painted by Govert Flinck, which depicts the portraits of the four governors [see Schaep fig. 10].47 Hanging in the third compartment to the right in the Hall of Honor, this piece (no. 31, formerly 18) allows one to possibly recognize the captain from the portrait with the Jan Roodenpoortstoren. One would seek in vain among those four gentlemen for another captain who is depicted sitting in the other large portrait in the council hall (no. 8, formerly 34) [fig. 10].48 Yet in the catalogue of the City Hall (the Historische beschrijving by Dr. Scheltema) we find no. 8 described as the company of Vlooswijck and no. 4 as that of Cornelis de Graeff, by Adriaen Backer. Fortunately, however, the elegant features of Cornelis de Graeff are known from the engraving by Houbraken after the portrait which is kept in the family [fig. 11]49 and from the marble medallion by Quellijn in the collection of the [Royal] Antiquarian Society.50 [His features] are well enough known to allow one to quickly recognize him [de Graeff] as the sitting captain in no. 8, in which the year 1642 can also be read; Schaep notes this as the company of De Graeff. Yet his portrait, to which we will return later, is identified as the company of Vlooswijck in Scheltema’s Historische beschrijving, an identification based on a nameplate that used to be attached beneath it, just like a similar one beneath the other portrait in the council hall. Loose nameplates are difficult objects to preserve in times of cleaning and moving, since the main people involved in these activities are perhaps people rather indifferent to whether the civic guardmen used to belong to the company of De Graeff or to that of Vlooswijck. I personally would rather adhere to the portraits themselves than to the tradition of the now removed nameplates and furthermore I would want to await the judgment of the art connoisseurs, as to which of these works in the council hall should to be attributed to Elias and which to Backer.

The nameplate for the De Graeff portrait includes twenty-three names, while the Vlooswijck portrait has only eighteen. This is yet further proof that no. 8, which contains many more figures than no. 4, depicts the company of De Graeff. During the writing of the Beschrijving in 1841 the nameplates had already been changed around, because one can read there: “A monumental civic guard piece with twenty-two portraits under Captain Cornelis de Graeff by Adriaen Backer. A ditto ditto with twenty-seven portraits under Captain Jan Vlooswijk also [sic!!] by Jacob Backer.”51 When Scheltema copied this, he changed the twenty-two portraits into twenty-three because otherwise it did not accord. Of course, it is possible to count all figures, [even those] with only an arm or foot, but twenty-three portraits, as the nameplate demands, can indeed be found in no. 8, but not in no. 4. The attribution of both these portraits to members of the Backer family started with the little book by Van Dyk.52 It is remarkable that Van Dijk attributed both portraits of Roch and Vlooswijk to the same painter — not to Elias, but to Jacob Backer. In the last one, he certainly could not have read the name, because already in Schaep’s time it was illegible, the first one was attributed to Elias with certainty by Schaep. Van Dyk did not mention dates. He attributed the company of De Graeff to Adriaen Backer53 and concurred with Schaep on this. At least to a certain extent. Nevertheless, this is not the present issue.

With this, however, we have still not found the work that Schaep also revealed to us as a portrait by Elias: the squad of Raephorst. Schaep did not mention a date, but in light of the names of the officers in this district (the fifth), it must have been painted between 1625 and 1638 [fig. 12].54 If we take away the pieces that have traditionally been attributed to a painter and the pieces we have identified by now, not many are left that could come from this time period that could possibly be attributed to Elias. And in none of these can I point out with certainty the portrait of Hendrik Lourisz, the bookseller “van ‘t water” [living on the Damrak], who is depicted in the portrait in the council hall wearing a skullcap and sitting next to Cornelis de Graeff; and [Lourisz] should be in the portrait we are seeking as a lieutenant to Raephorst.

No. 70 is a strong candidate, but because this is the latest of all the unknown paintings I believe this should be [identified as] the portrait by Backer that, according to Schaep’s list (Harquebusiers Civic Guard Hall [Kloveniersdoelen], no. 14) should be dated ca. 1638, because the Elias picture we seek can date from 1638, but also from 1625. Moreover, the latter was a chimney piece, and no. 70 seems too large for that. A better candidate, based on size, is the terribly neglected portrait no. 130,55 which still hangs in the writing-chambers. A building is depicted here, which, as we have seen, also appears in the other portraits by Elias. But [the identity of] this building, whether the Noorderkerk or one of the gates, is not clear anymore; it is not applicable to Raephorst’s district, which ran along the banks of the IJ from the Nieuwenbrug to the Haarlemmersluis.56

The portraits that belong together, that used to hang in the room of the Commissionerof the King and of which the first one (no. 127) has arrived at the [Rijks]Museum (in the small room no. 226) and the other has been entrusted to Prof. Wijnveld for restoration, are from 1623 and therefore too old.57 The same is the case with no. 77.58 This portrait is in the Hall of Honor (fourth compartment to the left). In Scheltema’s Historische beschrijving, it has been attributed to Moreelse, because there are twenty-one portraits in it, which is the same number as in Van Dyk’s no. 116.59 He [Van Dyk] gives the date 1603. If this is true, we would have a second portrait of treasurer Raep here (Schaep’s list, Longbow Archers Civic Guard Hall [Handboogsdoelen], no. 19).60 There are several beautiful portraits in this work, but others seem too weak to me for Moreelse. Whatever the case, this work (of which I am regrettably not able to provide its origins with certainty) is definitely not by Elias, and I finally have nothing left than no. 132 (formerly 95) , which is still at the Archives with the name of Jan Cuyper on a piece of paper held by one of the civic guardsmen (which gives no clue). But also in this portrait, I look for Hendrik Lourisz in vain, and the Rhine wine glass, with which the civic guards toast, sits on another holder (bekerschroef) than the one that was used by the Crossbow Archers Civic Guards (Voetboogsdoelen), according to painting no. 75.61 Moreover, the costume appears to be from before rather than after 1625.

It is also possible that the portrait with Raephorst is no longer present. Van Dyk rather explicitly described a portrait that, in his time hung in the former City Hall “above the entrance to the room of the Diemermeer” and in which no less than thirty-five civic guardsmen were depicted, meaning that if the sitters were lifesize this must have been a work of gigantic proportions. This portrait has disappeared without a trace. No portrait remains [that includes] so many persons. According to Van Dyk, it was painted by “Alion.” That name is not much different from Elias. Possibly this was the squad of Raephorst.

Now I bid farewell to Elias with the remark that regarding what I have said about his works, I do not want to hide behind the late A. D. de Vries, shirking my own responsibility. I do not doubt for a minute that he would have come to the same results as I, had he been able to continue his studies, but that did not become clear from his notes.

How did Van Dyk come up with his Alion? Probably by thinking of the A. Lion he mentioned elsewhere [in his Kunst of 1758]. This gives me the opportunity to ask attention for a second not well-known Amsterdam painter:

Jacob Lyon

Everything art history has to say of this painter was based on the two civic guard portraits in the City Hall attributed to A. Lion, no. 70 (formerly 36) and no. 71 (formerly no. 37). The first portrait (now in the fourth compartment of the Hall of Honor in the [Rijks]museum, on the right) bears no name, and the last one (now in the second compartment on the same side) includes [the inscription] A. Lont painted very clearly. It is impossible that both portraits were by the same hand. I have been no stranger to the idea that no artist with that name ever existed, and that it was all based on a mistake by Jan van Dyk. At one point, I thought I had found a trace of Lyon in a curious list of painters that appears in the notebook of the Amsterdam city-doctor Jan Sysmus, which used to be in the Van der Willigen library and which Mr. Papelendam later was so kind as to show it me.62 That manuscript mentions: “Francois Stellaerd van Lion, a Dutchman, painter of landscapes etc. vixit 1604.” Perhaps this was the father of Jacob Lyon. Schaep’s list convinces us that the latter had indeed existed. I owe knowledge of his first name to Mr. Abraham Bredius who provided me with a few notes indicating that in 1641 a painter of “around 54 years old” who lived in Amsterdam, wrote his name thus and was married to Magdalena van Ebelen. Mr. De Roever also found the name Jacob Lion, painter, a few times in the archives of the Weeskamer (1621, as living in the Wolvestraat, 1625, in the Reestraat).63

Schaep’s list (no. 11)64 makes clear that Lion executed a civic guard-portrait for the Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Hall (Voetboogsdoelen) just as it reveals that the captain was Jacob Pietersz Hooghkamer65 and the lieutenant Pieter Jacobsz van Rhijn, also officers of district 10 (facts that I have gleaned from elsewhere) [fig. 13].

The question which portrait is described here is not hard to answer, because it was described by Van Dyk in detail (p. 25): “painted by A. Lion 1628 with nineteen civic guards, this is already in a wholly different style of painting” (as opposed to the portrait by Cornelis Ketel mentioned before this one) “differing greatly from the last one, [for] here one can tell the captain, lieutenant, ensign and officers, from the common [civic guards], all standing knee height in full armor, with hats on their heads, but no name is known, it has been painted in a very detailed manner, the inlaid iron suits of armor, as well as the silver inlaid ornamentation, and the crosshatching of the same are depicted here so beautifully and purely that one has to wonder how a man who had painted with such a loose brush could have had the patience to execute so neatly the crosshatchings in the shadows that seem as if they had been engraved; the barrel of a gun, with yellow brass ornaments, and mother-of-pearl plates, has been painted so surprisingly naturally that it equals nature, this portrait has also been designed much more strategically correctly in its composition then any of the former works. In the background, one sees painting no. 366 as if it were hung on the wall.”67

This no. 3 is the painting by Dirk Barendtsz, with the inscription “In vino veritas.” It is therefore without debate that Van Dyk described painting no. 71 (as numbered by the city). Since apparently in its time the signature and date were still visible, this is the portrait meant by Schaep. Clearly the label reading “A Lont 1620” was mistakenly overpainted. The last number of the date will have been unclear, just like the first name. Lyon signed his name with a short J with a transverse line through it; if he did so on his paintings as well and connected the J with the L, this could easily have been read “A.L.” Regarding the date, in 1620 Hooghkamer was not yet captain. At the Crossbow Archers Civic Guild Hall (Voetboogsdoelen), the names of the painters of the portraits from that time were all known to Schaep. Thus it is impossible that a second portrait by Lyon hung there, and the old painting on the wall also proves that it cannot be from another civic guard hall.

But as to the question whether a second civic guard portrait by Lyon survived over there [in another civic guard hall], I also dare to answer no. His style of painting, so detailed, so smooth and so cool cannot be found anywhere else, in any case not on the portrait that in [Scheltema’s] Beschrijving of 1879 was also attributed to A. Lion; the no. 70 (now in the last compartment of the right side of the Hall of Honor). The older Beschrijving of 184168 even adds a date (1628, and gives this same date for the company of Hooghkamer, so this portrait did not yet carry the date 1620). If we may read 1638 instead of 1628, then the painting wrongly attributed to Lyon is probably by Backer and depicts the company of Alderman Hendrik Dirksz Spiegel (in Schaep’s list, Harquebusiers Civic Guard Hall [Kloveniersdoelen], no. 14). If 1628 is right, however, then it would be the company of Raephorst by Elias. But I give only little weight to the notes in the Beschrijving of 1841.69

Lastman and Van Nieulandt

One will look in vain for the names of these two painters in the catalogue of the new [Rijks]museum, since neither in the Trippenhuis70 nor in the Museum van der Hoop71 can one find works by them presently. Will those names now shine in the new [Rijks]museum, since Schaep’s list has taught us that the civic guard portrait that recalls the expedition of Captain Boom and his companions to Zwolle (no. 125 in the new numbering, presently in the Hall of Honor of the [Rijks]museum, fourth compartment on the left side) was “begun by … Lastman, but because of his death afterwards finished by . . . Nuland”? [fig. 14]72 Hofdijk already mentioned this in his Geschiedenis der Schutterij (1874), for which he had consulted Schaep’s manuscript without saying much about it, which was also less necessary in the context of Hofdijk’s work.73

The peculiarity of this portrait, however, had attracted [Hofdijk’s] attention and he even added how clearly he was able to distinguish one from the other painter. I, however, have to acknowledge my insecurity here, for I see, neither in the rendering of the figures, nor in the treatment of the landscape, nor in design nor in coloring, anything that recalls Pieter Lastman, the teacher of Rembrandt (or only perhaps when I seek it in the large-leaved shrub with the broken capital in the right foreground). Rembrandt only stayed with Lastman a short time, but [Rembrandt] understood so well what [Lastman] wanted and achieved it so beautifully, and [Rembrandt] often showed in small things that the memory of Lastman’s work had never been erased.

In his notes on Schaep’s list, Mr. Scheltema pointed out the date of Lastman’s death, 1649, while the painting, according to Schaep, is from 1623 (Scheltema, Aemstels Oudheid vol. 7, p. 140).74 The year 1649, however, is not right.75 Since Pieter Lastman continued living long after the date of the painting, it would be foolish to assume that it was left unfinished for so long. One could probably assume, therefore, an error in Schaep’s notes. This would not be such an unjustified guess, for, as we shall see later, he called Van de Valckert “Vlack” and Van de Voort “Van de Hoog”. Making sure that none of this will be blamed on A. D. De Vries, I will dare to give another hypothesis:

Schaep does not mention a first name and we therefore do not necessarily have to follow Misters Hofdijk and Scheltema in thinking here specifically of Pieter Lastman. There is no other painter known by that name, but Pieter Lastman did have a son Nicolaas, who engraved the title page of van Mander’s Schilderboek and also some prints after his father [Pieter], and after Pinas [Jan Pynas]; we do not know much more of him [Nicolaas].76 Is it improbable that this Lastman, who (given his age) took part personally in the expedition of civic guards, was commissioned to make this painting, and that after his [Lastman’s] early death Nieulandt was given the task to complete it? It has become increasingly clear to Mr. de Roever, that Claes Pietersz Lastman was buried on May 6, 1625. [His death did not happen] following a long illness, because he was still mentioned as a buyer at an auction on April 19, 1625.

Regarding Adriaan van Nieulandt, his detailed, nicely designed, colorful painting of Dam square with the procession of lepers on koppertjesmaandag [Koppertjes Monday or Lepers’ Parade][fig. 15]77 that still hangs in City Hall,78 gives no cause to doubt that he could have contributed to the civic guard portrait of which we speak. Because of the latter’s colorful splendor, great effect without [the appearance of] strain,79 by the good place it used to have in the cabinet of curiosities in the archives, and the fact that it is one of the few civic guard portraits that depict an actual historic event, it has become one of the best known.

Moreover, it is not necessary to think only of Adriaan with the name Nieulandt. From the notes that De Vries made consulting the marriage and baptismal records, it appears that another painter with that name lived in Amsterdam at the time, namely Jacob van Nieulandt, in the Pylsteeg, who in 1616, aged twenty-three, married Maria van Ray. He was probably a relative of Adriaan, because he was witness to the baptism of one of his [Adriaan’s] children (Pieter, born 1628).80 The same service [baptism] was granted in the Nieuwe Kerk to Adriaan van Nieulandt in 1618 by Isaac van Coninxloo and in 1620 by Margrieta Bartolotti. I mention these two names because they (the first a member of a family of artists, the second belonging to one of Amsterdam’s most prominent families) give a small hint of the good relations the painter had.

Pieter Codde

Because it has already been published by both Hofdijk and Scheltema, I only have to briefly highlight the “meager company” here, about which surely many an admirer of Frans Hals has already stopped shaking his head. This was dated “Ao 1637 started by Francois [Frans] Hals, and afterwards finished by Codde” [fig. 16]. If the design recalls Frans Hals, the finish leaves no doubt about Schaep’s statement that it was executed by a different hand. Recently Mr. C. M. Dozy has published extensively about Codde and his family in this journal (vol. 2, pp. 34 ff.).81 Honored for a long time by decorating the mayor’s chamber, nowadays it hangs in the [Rijks]museum to the right of Rembrandt!

The painting shows some civic guardsmen from district 12. The captain is Reynier Reael, the lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz or Michiel Cornelisz82 Blau.83 That the ensign is not Frans Hals himself, has long been known; that he, as Mr. Hofdijk writes, could be called Pieter Egbertsz Vinck is correct; he can, however, just as well be called anything else.

Originally the painting was placed in the new hall of the Longbow Archers Civic Guard Hall, opposite the chimney.

Regarding the portraits of the better known masters — Rembrandt and Van der Helst, Govert Flinck and Thomas de Keyser — I hope to include more details in a later installment.