Very few contemporary authors have written about the Utrecht painter Hendrick ter Brugghen. This makes the few words devoted to him by Joachim von Sandrart particularly precious to scholarship, especially because Sandrart characterized him as a man with “profound but melancholic thoughts” (“tiefsinnige jedoch schwermütige Gedanken”). In this article I will consider whether Sandrart’s words should be viewed as a mere topos meant to stress Ter Brugghen’s natural abilities as an artist in accordance with the concept of melancholia – the temperament most closely linked to scholarship and creativity – or whether Sandrart used these terms to characterize Ter Brugghen’s personality. After examining every instance of Sandrart’s terminology that relates to melancholy, I have concluded that Sandrart did indeed intend to categorize Ter Brugghen’s personality as melancholic, and that this assessment was based on his acquaintance with the artist during a stay in Utrecht in the 1620s. At the same time, I aim to demonstrate that Ter Brugghen was himself well acquainted with the concept of the melancholic temperament and that this impinges on our understanding of some of his works today, including a possible self-portrait that has hitherto been ignored.

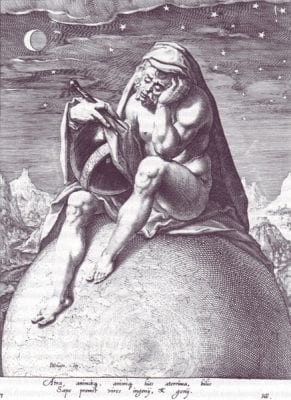

According to the ancient theory of the humors, artists and scholars alike are prone to melancholy. This psychological concept was still very much alive in the Dutch Republic, as evidenced by the caption to a print, designed by Jacob de Gheyn II (1565-1629), which was written around 1596/97 by the young Hugo Grotius (1583-1645): “Melancholy, that awful affliction of mind and soul / often suppresses the strength of talent and genius” (“Atra animaeque, animique lues aterrima, bilis / Saepe premit vires ingenij et genij”) (fig. 1).1

These words reflect the idea that the melancholic’s temperament is determined by an innate dominance of black bile in the body fluids, making the person grave and serious and inclined to withdraw into solitude and contemplation. Inward-looking, half-hidden in his cloak and with his head resting on his hand, the man depicted in the engraving sits upon the Earth (the element associated with melancholy) and holds a globe and a pair of compasses.

The theory of the humors provided a general principle by which to describe differences in personality. The melancholic, for example, is distinguished from the quiet phlegmatic who loves to eat and drink, the impulsive sanguine who tends to be social and merry, and the choleric who is energetic and often irascible. Although some concepts of the theory are still in use today, we must take care not to interpret appraisals of individual people living in the seventeenth century on the basis of the typological classifications of personality current in modern psychology and psychiatry. As long as we are aware of this pitfall, however, we may profitably investigate just what the Utrecht painter Hendrik Ter Brugghen’s contemporaries meant when they used these terms to describe individuals’ personalities. In this essay, I will do just that by assessing the remarks made about him by the painter and biographer Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688).

Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629) is known as a follower of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, the artist who radically changed history and genre painting in Italy around 1600. In the Northern Netherlands, Ter Brugghen is regarded as one of the most important of the Caravaggisti, but describing him as a follower of that great Italian artist does not do justice to Ter Brugghen’s own art. A passionate and innovative artist, he was constantly seeking new solutions to pictorial problems. Within a ten-year period, Ter Brugghen created an oeuvre that is often strikingly direct, characterized by keen psychological observations and a subtle use of color. At the end of his career he could no longer be called a Caravaggist, for by then he had found his own characteristic style.

Thanks to the recent publication of a new monograph with a catalogue raisonn é, written by the late Leonard Slatkes and Wayne Franits, we now have a reliable overview of Ter Brugghen’s extant oeuvre.2 We can also draw on the steady stream of scholarly contributions regarding specific aspects of his work that have appeared in journals and exhibition catalogues in the last few decades. Most of these publications dwell on Ter Brugghen’s paintings and his exceptional artistic personality, but there are many questions regarding his social position and the relationship between his work, his milieu, and his personal views that await further research – research that is hampered by the gaps in our knowledge of the artist.

To begin with, whole periods of Ter Brugghen’s life are undocumented. We know extremely little about his activities before he returned from Italy to Utrecht in 1614, for example, and we know hardly anything about his circle of friends, his patrons, or the early buyers and owners of his works. Moreover, there are very few contemporary written sources that yield substantial information about his personality, intellectual background, or religious convictions. His artistic views can be gauged through his work alone.

The nature of Ter Brugghen’s art – passionate, innovative, direct, and rich in keen psychological observation – reflects his personality. Of course, the problem of how, and to what extent, an artist reveals himself through his work has always been a hotly disputed issue among art historians. Although this avenue of inquiry is dotted with methodological and philosophical pitfalls, I maintain that knowledge of the personality of an artist is essential to understanding the aspects of his life that affect his work, and that this subject is therefore worthy of investigation. Common sense suggests that Pieter Saenredam needed a precise and patient personality to accomplish his goals, which required him to measure churches with great care, to transform their floor plans into elaborate construction drawings, and finally to depict their interiors with minute detail in his paintings. Rembrandt, despite his complex character, was first and foremost an artist bent on pushing back the boundaries of what could be achieved with paint and brush, and he was not easily satisfied with his own accomplishments. The unpleasant side of Rembrandt’s character – a side that has emerged in the course of a century of archival research – might at first seem irrelevant, but it leaves us wondering what else he might have painted had he been more skillful at maintaining contacts with wealthy patrons.

Judging from his work, Ter Brugghen was just as passionate an artist as Rembrandt, but this assessment, based on visual sources, leaves the historian yearning for written sources that could lead to a better understanding of his artistic choices.

Sandrart on Ter Brugghen

The only contemporary who recorded his observations on the personality of Hendrick ter Brugghen was Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688), who spent some time in Utrecht in the second half of the 1620s. In his Teutsche Academie, published in 1675, Sandrart writes about “Henrich Verbrug von Utrecht”:

In line with his inclination to harbor profound but melancholic thoughts he followed nature and its unpleasant defects in his works very well, but disagreeably. Similarly an unkind fate dogged him until the grave, to his great misfortune.3

The mention of “profound but melancholic thoughts” suggests the melancholic temperament which the theory of the humors attributes to the artistic personality.4 Some might be tempted to dismiss this as a mere topos, while others might wonder why Sandrart – unaware of today’s scholarly concept of topoi – applied it to Ter Brugghen.5 In my opinion, Sandrart deliberately chose these words to impart information about Ter Brugghen which he had gleaned from his personal acquaintance with the artist. He was not using the term indiscriminately when he called Ter Brugghen schwerm ütig, which in modern German translates as “sad,” “sorrowful,” ‘mournful,” “depressed,” or even “melancholy.” Sandrart might very well have been describing a trait he recognized in Ter Brugghen, and if indeed he did so, he provided his reader with important firsthand information regarding the artist’s character and mental make-up. Now, in order to buttress my argument, I must analyze Sandrart’s use of the terms tiefsinnig and schwerm ütig.

Sandrart employs the term tiefsinnig (profound) dozens of times throughout his book, and its connotations are invariably positive, signifying such traits as diligence and an inquisitive mind.6 This seems to support what Ter Brugghen’s oeuvre makes abundantly clear: the artist worked actively to find new solutions to pictorial problems. By contrast, Sandrart rarely uses the term schwermutig and applies it to artists only three times: once to Ter Brugghen and twice (following Vasari) to the Italian artists Morto da Feltro (ca. 1480-1527)(“Morto was a melancholic and lonely person”) and Daniele da Volterra (1509-1566).7 In reference to the latter, moreover, Sandrart uses the term to describe Volterra’s work rather than his character. Volterra’s character may well have been on his mind, however, [when] while writing about his work, because he later wrote explicitly that “because of his melancholic nature [melancholischenNatur] he enjoyed very little at all.”8 TerBrugghen thus remains one of the few “melancholic” painters whom Sandrart knew personally. Sandrart did not call him an outright “melancholic,” as he did Volterra, but he made it perfectly clear that the Utrecht artist fit this description.

Sandrart was well versed in the theory of the humors, to which he devoted a separate chapter in the first volume of his book on the art of painting (chapter 9: On the passions and emotions). He writes:

The artful painter should not only familiarize himself with the four human dispositions or natural temperaments, sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholic, but should also know how and why they blend. The effects of these are commonly called the passions or emotions, because they affect one’s state of mind the same way that physical afflictions affect the body. In our art this knowledge cannot be ignored, since these [passions] cause not inconsiderable changes in facial expression, posture and complexion.9

I have therefore studied the contexts in which Sandrart refers to these four types. He appears to have used only “melancholy” to refer to actual individuals and never describes persons as sanguine, choleric, or phlegmatic. Occasionally he applies “melancholy” to people afflicted with despair caused by external factors, a condition nowadays equated with mental depression brought on by life’s misfortunes. Sandrart was much more inclined to use the term to describe the innate personality of an artist, as in the following cases, most of which occur in older Italian sources:

– Andrea di Cosimo (Andrea di Giovanni di Lorenzo Feltrini), pupil of Morto da Feltro (see above): “He was good-hearted and diligent in his profession but very timid and profoundly melancholic, which might well have led to suicide.”10

– Francesco Salviati: “Francesco was by nature lonely and shunned the company of others and was also very melancholic while working.” 11

– Pietro Testa: “was always sunk in his own thoughts and spent his life in melancholy, in other words, with little joy.”12

– Matthaeus Grünewald: “led a withdrawn, melancholic life and was unhappily married.”13

– Pieter van Laer: “As far as his life is concerned, I can truthfully report, having been one of his closest friends, that his mind was overburdened by constant reflection and contemplation. . . . Given his fragile and delicate disposition and his tendency to be melancholy, his strength and memory declined with age, conveying this devout and singular man from temporal anxiety to eternal rest.”14

I conclude that Sandrart was consistent in applying these epithets, not only to artists he had known personally but also to those long dead. In the latter case, he relied on earlier sources, interpreting them within his own theoretical framework. This bears out my hypothesis that Sandrart’s short characterization of Ter Brugghen contains valuable firsthand particulars about the artist’s personality, information that is more valuable than the commonplace biographical details we tend to call literary topoi.

It is a pity, therefore, that Sandrart is not more explicit about the end of Ter Brugghen’s life. He does not elaborate on the cause of the artist’s early death at the age of forty-two, saying merely that (as quoted above) “an unkind fate dogged him until the grave, to his great misfortune.” Reading between the lines, however, one feels that he met an unhappy end.

Ter Brugghen and the Theory of the Humors

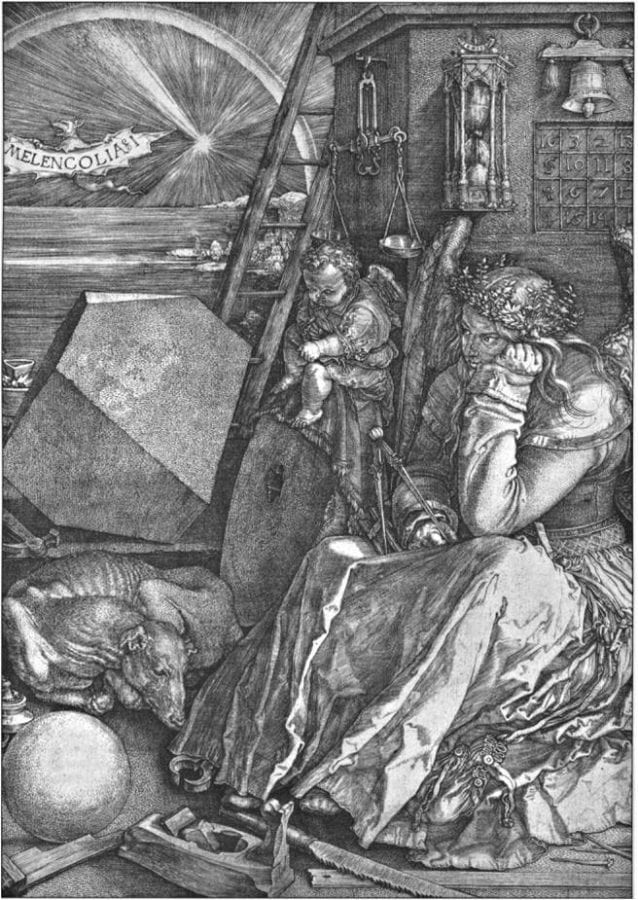

There can be no doubt that Hendrick ter Brugghen, like Joachim von Sandrart, was well acquainted with the theory of the humors and with Melancolia as a subject in art.15 At the end of his life, around 1627-28, he painted an impressive depiction of a young woman as Melancolia (fig. 2), which Sandrart may have seen in Utrecht.16 This picture was previously identified as a mourning Mary Magdalene, but Slatkes has rightly pointed out that the hourglass and the pair of compasses serve here (as in Dürer’s famous print of 1514) (fig. 3) as attributes of Melancholy, indicating that the woman is entirely absorbed by her contemplation of scholarly problems, so much so that she must rest her head on her hand.17 The melancholic tends to retreat into loneliness and darkness in order to meditate, and Ter Brugghen’s addition of a skull suggests that human mortality is the subject of her meditation.18 In my opinion it is even possible that Ter Brugghen intended to combine a personification of melancholia with Mary Magdalene mourning the death of Jesus.

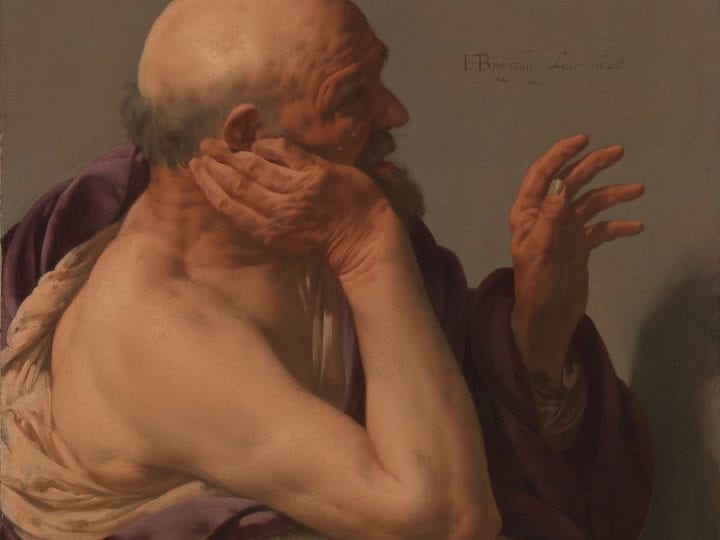

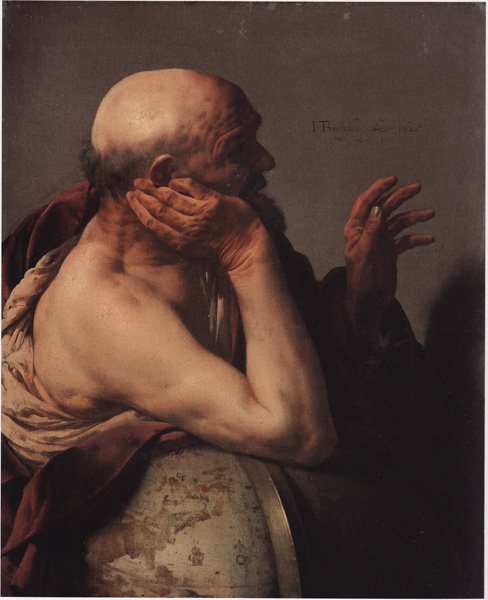

The same pose and the same dark shadow hiding the eyes of the model can be found in a depiction of the grieving philosopher Heraclitus in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 4).19 This painting and its pendant of the cheerful Democritus date from 1628, the year before Ter Brugghen’s death. Even the famous Sleeping Mars (ca. 1625-26, though a different subject altogether, exhibits the characteristic pose of the melancholic) (fig. 5).20 As in Melancolia and Heraclitus, the eyes of the sleeping Mars are covered by dark shadows. This detail recently led Eddy de Jongh to hypothesize, albeit cautiously, that in addition to the archetypal melancholic (“in a pensive pose, resting his head on his hand”), a heavy shadow cast over the face may be a meaningful pictorial element.21 He thus agrees with Perry Chapman, who previously argued on the same grounds that Rembrandt similarly depicted himself as a melancholic in some of his early self-portraits (fig. 6).22 De Jongh therefore assumes that Rembrandt intentionally portrayed the stodgy poet Jeremias de Decker – “Heel goed joks en ben ick niet” (“I am not much of a joker”) – by making the wide brim of his hat cast a heavy shadow over his eyes (fig. 7).23 He remains cautious, though, acknowledging that very few portraits lend themselves to this interpretation and that obvious shadows may be of only secondary importance in interpreting these images. Nevertheless, seen in the light of the early-modern theory of the humors, his conclusion is very plausible indeed.

Summing up my arguments thus far, a strong case can be made for Ter Brugghen’s melancholic personality, at least in the eyes of one of his contemporaries. There is also sufficient evidence to support the theory that Ter Brugghen consciously applied the notions of the four temperaments, including melancholia, in some of his own works. I will now become much more speculative and argue that Ter Brugghen depicted himself in a fashionable mode, with melancholic overtones, in a self-portrait that is now probably lost.

Hendrick ter Brugghen as Portrait Painter

At the end of his long life, Richard ter Brugghen (1619-1710), the only son of Hendrick ter Brugghen, published a “Notification or warning to all Lovers of the art of Painting” (Notificatie of waarschouwing aan alle Liefhebbers van de Schilderkonst, etc.’). In this pamphlet, intended to boost the waning reputation of his father, Richard wrote among many other things that his father was “very skilled in portraiture, rendering [the sitter] in such a natural way, that only life seemed to be wanting.”24 Unfortunately, the only known portraits by Ter Brugghen are those mentioned in old references, but there are indeed two prints that provide us with a glimpse of this aspect of his artistic activities.25

Richard commissioned the Utrecht engraver Pieter Bodart (after 1668-1713) to make two prints after a portrait of Hendrick ter Brugghen.26 The first (fig. 8) depicts a typical Caravaggesque half-figure, gazing at the viewer in an unrestrained yet attentive way. The other (fig. 9) is completely different in character, although the (reversed) face is identical. Here the artist is portrayed very formally as pictor doctus and grand seigneur, sporting the coat of arms of the noble Overijssel family of Ter Brugghen (argent, three holly leaves; 2 and 1, sinople). In both pose and manner, this portrait follows Sir Anthony van Dyck’s depictions of famous artists, published from the 1630s onward in his Iconographie, the copper plates of which were probably in Utrecht in the period 1677-1720.27 Below the caption, the name of the Utrecht painter Gerard Hoet (1648-1733) appears as the designer of the preliminary drawing (“del[ineavit]”). It is likely that this portrait is largely Hoet’s invention, apart from the facial features, which must derive from the same source as those in Figure 8. Benedict Nicolson considered the possibility that Hoet’s portrait was based on an “earlier likeness” but nevertheless thought the print “distressingly posthumous.”28 Slatkes and Franits are not sure if the print was even based on a likeness of the artist.

The engraving of the man in a more relaxed pose (fig. 8) has been reproduced only twice in the modern art-historical literature, and no author has examined its significance as a source for Ter Brugghen’s physiognomy.29 Nicolson was unaware of its existence, and Slatkes and Franits apparently did not see any point in illustrating it.30 In my opinion, however, this print reflects an earlier self-portrait that is now lost, the main reason being that it was the artist’s son who commissioned the print. Even though Richard ter Brugghen was a very old man at the time there is insufficient evidence to undermine his claim that this was his father. One might argue that Richard ter Brugghen is known to have occasionally strayed from the truth – he was a lawyer after all – but why would he have picked any old drawing or painting to serve as his father’s portrait?31 It is simply much easier to conceive that a record of Hendrick ter Brugghen’s physiognomy was kept by his widow and children and that this is that record.

Apparently at the beginning of the eighteenth century no formal portrait of the type produced by Ter Brugghen’s contemporaries Paulus Moreelse or Michiel van Mierevelt was available to Richard ter Brugghen for reproduction, which leaves us with the necessity of explaining the appearance of this informal portrait. In my opinion, it is most likely based on a (now lost) self-portrait. With his slightly tilted head and his inquisitive look, the sitter appears to be looking into a mirror. The engraving is obviously in reverse, but as is the case in so many self-portraits the artist’s right hand holding the brush is not included. Instead, the arm is hidden in clothing. Whether the original was a drawing or a (detail of a) painting is unclear because the caption below the Bodart print only gives the name of the engraver and not – as in the case of the formal portrait (fig. 9) – that of the designer. Information on the technique of the original (painting or drawing) is not given either. Apparently Richard ter Brugghen wanted to have this portrait reproduced because of its authenticity. He may also have wanted a portrait print that reflected the social status of his father.

We know that Richard conducted extensive genealogical research to prove his noble descent and that it was customary in those days to have new, “improved” portraits made of ancestors on the basis of older but authentic portraits. The formal portrait (fig. 9) is a good example of such an “improved” version, with clothing à l’antique, a classical backdrop with a curtain, and the family arms prominently displayed.

Cornelis de Bie, to whom Richard ter Brugghen sent both prints and an accompanying letter, considered them true-to-life. He wrote (in verse): “To me a picture of Ter Brugghen has been sent / Handed over as a print, a perfect likeness / Clearly done from life, an image flawless / And thus inserted in my book on painting.”32 The “book on painting” in question was De Bie’s own copy of his Gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst of 1661, in which he had devoted a short paragraph to the work of Ter Brugghen, though under the misnomer “Verbrugghen” and without a portrait of the artist.33 Several decades later this prompted Richard ter Brugghen to urge De Bie to rectify the omission and may also explain why he had Bodart adapt the two prints, in both format and inscription, to fit into the series of artists’ portraits first published by Johannes Meyssens in 1649 and subsequently added to the Gulden cabinet.

These observations suggest that Bodart’s first engraving (fig. 8) is indeed based on a lost self-portrait and may therefore be the only extant record of Ter Brugghen’s activities as a (self-) portrait painter. But why did Hendrick ter Brugghen portray himself in such an informal way? Did he do this on purpose, or was the original painting just a genre piece based on the artist’s own likeness? Ignoring for the time being the latter option, I wish to explore the possibility that Ter Brugghen did indeed intend to portray himself in an informal pose.

Lossigheyt

The sitter in the “authentic” portrait (fig. 8) wears an unbuttoned shirt, and his outer garment is falling off his shoulders. This is quite common in Ter Brugghen’s history paintings and genre pieces, but it is unheard-of in early seventeenth-century portraiture in the Low Countries, which remained very formal. All the same, even before 1620 it had become highly fashionable at the French and English courts for young courtiers to dress with a certain négligence (carelessness). The term goes back to Baldassare Castiglione’s famous book on the courtier, in which he introduces the concept of sprezzatura, which could be applied to behavior as well as to appearance and dress. Marieke de Winkel has collected ample documentary evidence to prove that this negligence, or lossigheyt (looseness) as it was called in Dutch, also became popular in the Dutch Republic.34 The negligent mode in portrait painting, however, did not become widespread until mid-century, Rembrandt’s portrait of Jan Six being one of the best-known examples.

This fashion of lossigheyt insinuated itself into many aspects of contemporary culture, not only dress but also poetry and painting. In 1636 the poet Johan van Heemskerck, for example, wrote that the paintings of contemporary masters had profited much from “a rougher brush and bolder hand” than that seen in the work of masters from the previous generation.35 Ter Brugghen’s own handling of the brush, however, became increasingly smooth over the years, a fact which is rather inconsistent with this trend. Thus, free brushwork as a manifestation of lossigheyt does not apply to Ter Brugghen. Nevertheless, his frequent depiction of genre figures in very informal attire testifies to his awareness of this fashion. Thus the figure in the Bodart print (fig. 8) is in keeping with those in Ter Brugghen’s genre paintings from the 1620s. If indeed Ter Brugghen meant the (original) drawing or painting to be a self-portrait, as I argued above, rather than a tronie or a genre figure, he aligned himself with the fashionable courtiers and scholars of his day.

From early on, the “loose” way of dressing was associated with scholars and artists: in other words, the creative world of the archetypal melancholic.36 Yet the négligence that was so fashionable in Ter Brugghen’s day should not be regarded as synonymous with melancholy. It would be going too far to read more into the pose and the shading of the face in Bodart’s print than there is, the more so because all the other attributes of melancholy are lacking. The figure does not turn inward but looks inquisitively at the viewer, or for that matter through the mirror at his own outward appearance. The shadow over his left eye is cast by the light falling from the upper left in a more or less natural way, as opposed to the intentionally dark shadows Ter Brugghen used in Melancholia (fig. 2) and Heraclitus (fig. 4). Assuming that Bodart made his print after a lost self-portrait, we can, however, conclude that Ter Brugghen “fashioned” himself after the latest mode, in which melancholy was in vogue. This seems to be consistent with our findings in the first part of this article.

Conclusion

I am aware that I have been walking on thin ice, but the lack of sources clarifying Hendrick ter Brugghen’s psychological makeup (apart from the few remarks by Sandrart discussed here) have left me little choice but to come forward with either a bold hypothesis or a piece of sensible speculation. The searchable, on-line edition of Sandrart’s Teutsche Academie enabled me to do the latter, namely to speculate about Ter Brugghen’s supposed melancholic temperament. I have concluded that Sandrart’s observations cannot be dismissed out of hand, especially since Ter Brugghen himself applied the doctrine of the four humors in his work. Slatkes and Franits warned against interpreting Ter Brugghen’s Melancolia or any other of his works in a purely autobiographical way, “although there will probably always be attempts to do so.”37 Yet careful reading of Sandrart’s text does in fact suggest that the relationship between the personality of the artist and some of his works is a subject worthy of in-depth study.38

Clearly, one must bear in mind that when Joachim von Sandrart wrote his Teutsche Academie in 1675, Ter Brugghen had been dead for almost half a century. And Sandrart the artist had changed considerably since his youthful days in the Utrecht studio of Gerard van Honthorst. The opinion he expressed, namely that “he [Ter Brugghen] followed nature and its unpleasant defects in his works very well, but disagreeably,” was formulated after artistic tastes had undergone fundamental changes and the stark naturalism of the Caravaggio school had gone completely out of fashion. But when Slatkes and Franits qualify these as “defamatory remarks” or even “vilification,” they ignore the fact that Sandrart judged Ter Brugghen’s work to be of high quality (“sehr wohl”), and that he provided us with important firsthand information about his personality.39 Just as I have done here in the case of Ter Brugghen, Eric Jan Sluijter recently offered a reassessment of Sandrart’s judgment of Rembrandt, arguing that it, too, was based on close personal observation and is therefore relevant to art history, even though Sandrart’s observations were colored by the artistic rivalry that developed between these two masters when they were both working in Amsterdam.40

![Hendrick ter Brugghen, Sleeping Mars, signed and dated 162[5 or 6?], Centraal Museum, Utrecht](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Bok1.2_fig05new-defa.jpg)

![Hendrick ter Brugghen, Sleeping Mars, signed and dated 162[5 or 6?], Centraal Museum, Utrecht](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Bok1.2_fig05new-defa-112x84.jpg)