After a hiatus of nearly twenty-five years, Thomas de Keyser painted several additional portraits, apparently a by-product of family and professional connections. Among these was his masterful small-scale equestrian portrait of twenty-year-old Pieter Schout (1660), a young lawyer with high cultural and political ambitions. With new archival documentation, this essay recreates the biographical, familial, and social networks that must have brought artist and patron together, with a consideration of the social import of the painting for its sitter and subsequent owners.

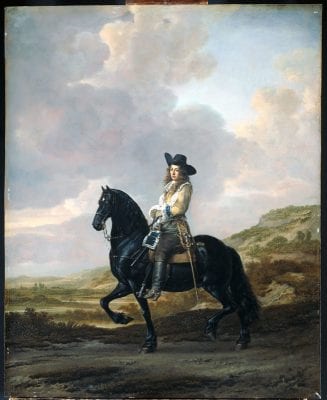

Walter Liedtke first came to the Department of Paintings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1979 on a Mellon Fellowship to write what became his award-winning book, The Royal Horse and Rider: Painting, Sculpture and Horsemanship 1500–1800, published in 1989.1 When I arrived in the department two years later as a Chester Dale Research Fellow to work on my PhD dissertation on the paintings of Thomas de Keyser, Walter—who had the previous year been appointed the museum’s first curator of Dutch and Flemish Paintings—was deeply immersed in his research for the book. I recall with pleasure our discussions over photographs of equestrian portraits piled on the large round table in his office, among which was one of the masterpieces of the genre, de Keyser’s small-scale equestrian portrait of nineteen-year-old Pieter Schout (November 14, 1640–May 29, 1669) now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (fig. 1).2 Painted on a large sheet of copper in fine yet visible strokes, the surface has a gemlike quality.3 With a few exceptions de Keyser had, some twenty years earlier, traded his portrait brush for a chisel to make a living as a stonemason and contractor. This painting, along with two other small-scale equestrian portraits painted in his sixty-fourth and sixty-fifth years, however, did not constitute a return to portraiture as a profession per se but seem to have been a by-product of family and professional connections in other spheres.4 This essay assembles the disparate information about de Keyser’s portrait of Pieter Schout and the equestrian practices and the visual tradition of which it partakes. Then, with new archival research, it fills out the provenance and identifies Schout’s family and the social networks that must have brought patron and artist together, concluding with a consideration of the afterlife of the painting.

The inscription on the third state of a print after the painting by Abraham Blooteling identifies the subject of de Keyser’s portrait as Pieter Schout (see fig. 7). Schout’s father, Bartolomeus Jans Schout[en] (1612–1676), was Pagadoor van ‘t krijgsvolk (paymaster of soldiers) of Amsterdam.5 Pieter’s mother, Jannetje van Oirschot [Joanna van Oorschot] (1615–1680), was the daughter of a French schoolmaster in Alkmaar north of Amsterdam.6 The couple published the banns of their marriage in Amsterdam on May 22, 1637, and were married on June 9.7 Pieter Schout was their second son and, according to the inscription on the print was born on September 14, 1640. He was baptized in the Nieuwe Kerk on September 23.8 Schout died unmarried at the age of twenty-eight on May 29, 1669, and was buried in the same church on June 1, 1669.9

Until 1880 when a descendant donated the painting to the Rijksmuseum and Victor de Stuers recognized de Keyser’s monogram, the portrait had been attributed to artists on whose styles de Keyser had had a significant impact. When Blooteling’s print was recorded in an Amsterdam sale in 1767, the sitter was named as Pieter’s father, Bartholomeus Schout, and the artists as Gabriel Metsu and Philips Wouwermans.10 In his multivolume catalogue raisonné published in 1829 John Smith listed it among the works of Caspar Netscher, attributing the horse to Philips Wouwermans and listing the sitter as unknown; in his supplement of 1842 Smith changed the attribution of the figure to Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681).11 Even after de Keyser’s monogram was discovered, because he is primarily known for his portraits authors seemed to have been unwilling to credit him with either the horse or the landscape. In 1927 Hans Schneider gave the landscape to Adriaen van de Velde, an attribution repeated in subsequent literature.12 The handling of the paint is consistent throughout the work, however, and there seems to be no reason to attribute the landscape to another artist.13

Schout is comfortably seated astride a small-headed black Andalusian, which is painted with such care and specificity that it, too, must be a portrait.14 Both Schout and his mount are lavishly outfitted. Small colored tassels hang from his horse’s bridle. Schout himself wears a satin jacket with slit sleeves, high boots and spurs, and a hat with a thin metallic braid at the edge of the brim. A sword with a lion’s head handle hangs from the baldric over his shoulder, which is elaborately embroidered in gold and silver thread. Schout’s pistol is tucked into a blue holster trimmed in silver satin, while a broad blue bowed band is tied around his left wrist. Beyond him stretches a vista over a rolling dunescape.

Seventeenth-century Equitation

While measuring less than eighty-six centimeters (thirty-four inches) high, Pieter Schout’s portrait has the dignity and authority of life-sized equestrian images of nobility, whose prestige it invokes. It locates him in a long tradition of magnificent equestrian figures ranging from the antique statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome (175 CE) to Titian’s Charles V at Mühlburg (1578) and Anthony van Dyck’s Equestrian Portrait of Charles I (ca. 1637–38).15 Although work horses hauling carts to market and coaches between cities were a familiar aspect of daily life, following international court fashion the ownership of an elegant riding mount and skill in dressage was becoming an important social skill for the Dutch urban elite. In the late 1640s, Dutch painter Gerard ter Borch had painted at least two small-scale equestrian portraits for non-Dutch royal patrons: one of Henri d’Orléans, duc de Longueville (1646/47; fig. 2), and another of Elector Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz (1649).16 At mid-century artists began painting larger and even life-sized portraits of non-royal Dutch sitters, including Rembrandt’s portrait of Frederick Rihel (ca. 1663).17 In Dordrecht, where regents had begun adopting country lifestyles, Aelbert Cuyp had been painting more narrative multifigured equestrian portraits from the 1650s.

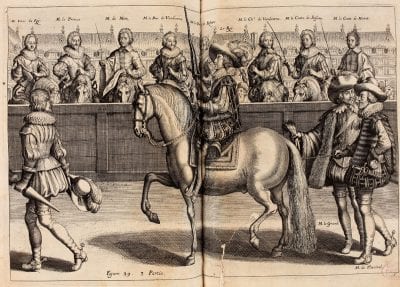

Customarily reserved for monarchs and aristocrats, the genre had been associated with leadership in battle and the privileges of the hunt. During the seventeenth century equestrian training in classical dressage (haute école) had become popular among Europe’s elite, as attested to by a number of books illustrating its techniques, including Antoine de Pluvinel’s L’Instruction du Roy en l’exercice de monter à cheval of 1625 written for the French king (fig. 3).18 An appreciation for dressage quickly spread to The Netherlands. Living in exile from 1648 to 1660, Englishman William Cavendish wrote and published his influential Methode et invention nouvelle de dresser les chevaux in Antwerp in 1658.19 Although little documentation survives, around this time private riding schools had begun to be established in Amsterdam.20 The majority of formal equestrian portraits depict the figure in one of the established riding poses, most frequently either the more difficult levade, or the piasse as executed by Pieter Schout and his horse, a highly collected trot in place in which the horse stands on one fore- and one hind leg as it raises the two opposing legs off the ground.21

Schout and the 1660 Entry of Maria Henrietta Stuart and Prince Willem III

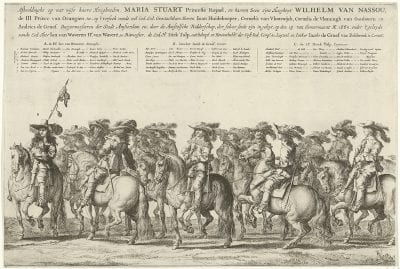

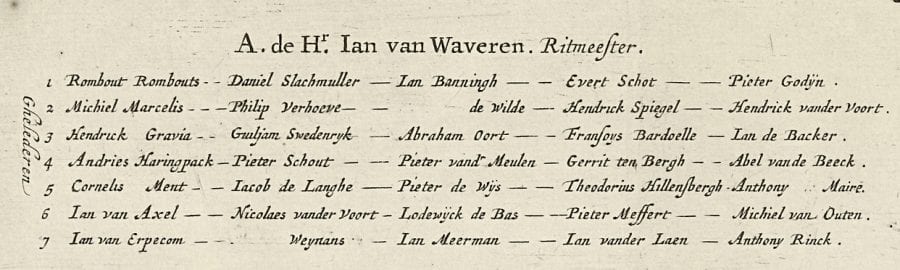

Although de Keyser’s portrait makes no reference to other riders, as first observed by D. J. Meijer in 1888, the idea of celebrating Schout and his equestrian skills may have been prompted in part by his participation in a cavalcade hastily assembled in June of 1660, the year inscribed on the painting, as part of a celebration to honor Maria Henrietta Stuart (November 4, 1631–December 24, 1660) and her nine-year-old son Willem III, Prince of Orange (November 14, 1650–May 8, 1702).22 Remmet van Luttervelt noted that Jan Vos’s poem written about the painting (text below) mentions Schout’s helping to greet the “Oranjen,” members of the House of Orange, while Jonathan Bikker observed that Schout’s participation in the cavalcade was recorded in the inscription on a print published to memorialize the event (fig. 4, fig. 5).23 With a few modifications, the plate for the print had been reused by an anonymous printmaker after that created by Pieter Nolpe for the 1638 entry of Marie de’ Medici into Amsterdam. While Schout is not specifically portrayed in the print, his name is listed among the 108 members of the cavalcade that were added to the earlier plate.24

This was a highly visible position in a notable event. While the reigning Amsterdam burgomasters and town council continued to be opposed to the return of the Stadhouderate, which would go to young Willem III, they swallowed their opposition in the hope of currying favor with his uncle, Charles II, newly restored to the English throne. On June 15, 1660, the coaches of Maria Henrietta Stuart and her nine-year-old son Willem III, and their retinue, approached the city of Amsterdam. “About an hour outside of the city gates” they were met and escorted to the Sint Anthonispoort by an honor guard consisting of over one hundred cavalrymen. The riders were divided into three cavalcades comprising not only members of regent families but also affluent citizens from many different circles.25 Schout was among the fourth group of riders in the first and most prestigious group of riders, under the direction of Jan [Joan] van Waveren (see fig. 5). If the painting refers to the cavalcade, the blue ribbon around his wrist may refer to the group of horsemen of which he was a part.26 Companies of the civic guards welcomed their visitors the following day and escorted them through the city past twenty hastily assembled and decorated staatsiewagens (floats) on the Dam whose programs were written by city glazier, poet, and head of the Amsterdam theater Jan Vos (1610–1667).27

The honor guard in which Schout rode was meant to impress the royal guests. It also was the kind of public ritual that helped to cement participants within the city’s social and political foundations and, by extension, the province of Holland, the Republic, and abroad to England. Pieter Schout must have appreciated this as an exceptional opportunity to further his own rapidly rising social and political stature.

While de Keyser’s three equestrian portraits of 1660 and 1661 have traditionally been cited as the earliest non-royal equestrian portraits on a small scale, Frederik Duparc has recently demonstrated that Adriaen van de Velde had already created an exquisite small-scale non-royal equestrian portrait in 1658 (fig. 7).28 Accompanied by a dog, Adriaen van de Velde’s figure evokes the prestige associated with the hunt. For the moment, its sitter remains unknown, but de Keyser’s portrait of Schout is so close in concept and pose that he must have known the earlier work.

Because de Keyser’s portrait makes no reference to other riders, a city gate, or even a suburban setting, it is possible that this painting was linked to the event only after the fact. Given his subsequent official appointments in Utrecht and Hagestein, Schout must have owned land in this region.29 If an occasion prompted the commission, it is thus possible that it might depict another still unknown event in Pieter Schout’s life, such as his receipt of an inheritance or the purchase of a country home.

Drost and Dijkgraaf of Hagestein

As Jonathan Bikker noted, two years after Schout’s participation in the cavalcade he graduated from Leiden University with a degree in law; two years after his graduation, on September 3, 1664, Schout was appointed by the chapters of the cathedral and Oud Munster of Utrecht to the position of Drost and Dijkgraaf (high bailiff and overseer of the local water authority) of the domain of Hagestein, a community south of Utrecht on the Lek River.30 Bikker points out that because the appointment was made by the chapters of the church, it was the reason he was also called canon or warden of the cathedral and Oud Munster.31 By this time Schout was establishing himself in Amsterdam as a young man of culture, for in 1664 Jan Neuye dedicated his play Eneas of Vader des Vaderlants to “Den Heer en Meester Pieter Schout, Rechts-geleerde, Dom-Heer van Oudt-Munster, & etc.”32

Pieter Schout and Thomas de Keyser

If Schout or a member of his family did not already have a relationship with de Keyser, the commission—coming after nearly two decades in which the artist does not seem to have created any portraits—must have been brought about through an individual with whom de Keyser had established ties. In 1635 Pieter’s father, Bartolomeus Schouten, purchased a “d’hemelvaert van Muller f –:14:” at the Barent van Someren sale, at which de Keyser also made a purchase.33 On May 17, 1644, Bartholomeus Schout purchased from Dirck van Wisselt a house and property on the west side of the Keizersgracht.34 De Keyser had portrayed Dirck van Wisselt and his son in 1631.35 Moreover, de Keyser had recently portrayed Cornelis de Graeff (1599–1664) and would at about the same time portray his sons Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707), and Jacob de Graeff, the latter of whom led one of the three cavalcades of the 1660 event.36 Artist and sitter also both knew Jan Vos, who had written the program for the Stuart-Orange entry. Thomas [Hendricksz] de Keyser’s first cousin Thomas Gerritsz de Keyser (ca. 1597–1651) was an actor in the Amsterdam theater. Vos was also well known to Pieter Schout’s family. Over the years the poet had written a considerable number of occasional verses on family members, family events, portraits, and a history painting owned by his parents.37 Vos also wrote poems celebrating every stage of Pieter Schout’s own career: on this equestrian portrait and presumably his participation in the cavalcade of 1660; on his graduation from Leiden in law; on the dinner in celebration of his appointment as Duikgraff of Hagestein (in a poem that calls him “Domheer van Out-Munster, &c” [Canon of Old Munster]); on (possibly another?) portrait in which his appointment as Drost and Duikgraaf of Hagestein is also mentioned; and finally, in the voice of an actor addressing Schout, published two years before the dedication of Eneas.38 Schout’s social position is displayed by the title “Den E[del] Heer” (The Noble Lord) by which he was designated in all of these texts.

Afterlife of the Portrait

De Keyser’s portrait of Schout almost immediately became the subject not only of Vos’s poem but also of a reproductive print by Abraham Blooteling and a second poem by Jacobus Heiblocq. It thus provides an instructive example of the means by which a portrait was subsequently used to assert social identity and claim cultural status by surviving family members. First appearing in a collection of verse published in 1662, Jan Vos’s poem was thus penned shortly after the painting was completed.39 It reads in translation:

The Noble Lord Pieter Schout Painted on His Horse.

Thus people saw Schout, when he helped to welcome the House of Orange.

He does not have to yield to Castor in the way he handles a horse.

He who wishes to meet the court, ought to be splendid in everything.

He shows himself ready, to use the glittering sword,

And thundering pistol, when it is necessary.

Bravery provides the cities with a shield.

Whoever loves Freedom justly protects her from downfall.

His desire for knowledge, which never wastes time,

And judgment about art, provides material for poetry.

He who is rich in gifts knows how to oblige everyone.40

The painting itself makes no obvious reference to Schout’s participation in the 1660 cavalcade; it is thus possible that the association of the painting with the event for which Vos had written the program may have been subsequently been made by the poem only after de Keyser finished the painting. During Schout’s lifetime, then, painting and poem celebrate his social position. After Schout’s death in 1669, the painting continued to play a role in the social identity of its subject, as well as that of its subsequent owner.

The engraver Abraham Blooteling reproduced the painting in an imposing print, the copper plate for which in 1880 was still in the collection of the last descendant of the family.41 Roughly two-thirds the size of the original, the print is inscribed in the upper right corner “A. Blooteling sculp.” Although born and trained in Amsterdam, Blooteling worked in Paris from 1660 to 1665. Mary Curd has observed that the spelling of the engraver’s name with a double “o” appears only on prints dating from December 1670 and later.42 These facts suggest that the engraving was commissioned posthumously, probably by his parents, shortly after Schout’s death in 1669.

Blooteling’s print was first engraved and printed with no room for a caption. In its third state a caption was squeezed into the margin of the plate, giving Schout’s name along with his birth and death dates, degree as a lawyer, and “Canonicus Ultraject. Satrapes Hagesteinae”(Canon of Utrecht and Lord [High Bailiff] of Hagestein), to which he was appointed in 1664. This state is also accompanied by a Latin eulogy by Jacques Heiblocq (Amsterdam 1623–1690) in letterpress from a different plate (see fig. 7).43 Well known to us now for the album amicorum that he kept between 1645 and 1678, Heiblocq’s verse on the plate is signed “Gymn: Amst: in nova urbis regione Rector.” Like the print, then, this verse must date to after 1670 when Heiblocq was appointed rector of the Latin school on the Gravenstraat, and it moved to the Singel.44

It is rare that we can trace the provenance of a painting back to its original owner, but a complete provenance for de Keyser’s portrait is now possible. It would have nearly certainly been commissioned by either Pieter Schout himself or his parents, and upon his death in 1669 it reverted to his parents, if it was not at the time in their possession. In 1672 Bartolomeus Schout became the godfather of Pieter Schout Muilman (1672–1757), the son of Hendrick Muijlman (1644–1709) and Regista Lakeman (1643–1716).45 This distant cousin and namesake was the father of Daniël Roelof, in whose inventory the painting first appears in 1801.46 Upon the death of Pieter’s parents, or possibly upon the baptism of Pieter Schout Muilman in 1672, the painting must have been given to this cousin.47 It can then be traced through the Muilman family to the last remaining collateral member of the family, the stepson of Anna Maria Mogge Muilman (1811–1878), Jonkheer Jacobus Salomon Hendrik van de Poll (1837–1880), who, upon his death, bequeathed it to the Rijksmuseum.48

De Keyser’s portrait of Pieter Schout—very possibly intended for Schout’s own cabinet of paintings—originally displayed his equestrian skills as well as his taste for finely crafted works of art and then served a variety of cultural purposes for himself and then other family members before, and after, his death.