Gerard de Lairesse produced an astonishing number of paintings during his active years in Amsterdam from 1665 to 1689. Given his numerous pupils, known through biographers, one may wonder to what extent De Lairesse’s masterpieces are collective undertakings. This essay proposes a new approach to studying workshop practice in the seventeenth century through a combination of quantitative analysis and biographical research. This essay visualizes the overall trend of the artist’s painting production and situates the pupils’ training periods in the master’s career timeline. The analysis shows that De Lairesse’s painting production fluctuates with the change of the quantity and quality of pupils present in his workshop. This essay further reveals the workshop’s participation in large-scale commissions for decorative paintings, which also explains why and when the master had more time for making collector’s paintings by himself.

“If we, painters, need an assistant, then it is not to show what such a person is able to do to enhance his own fame or honor, but to help execute the work of the inventor or first master according to the latter’s approval . . . in such a way that the whole piece not only acquires a general welstand, but, and that is more important, seems to be painted by one hand.”1 Thus Gerard de Lairesse instructed his fellow master painters in his Groot Schilderboek, after having had a prolific career as a painter himself in Amsterdam between 1665 and 1689. He even warned the reader that when an assistant fails his instructions, “the dignity and gracefulness of a beautiful composition is ruined, yes, destroyed, and thus provokes scorn and ridicule of connoisseurs.”2 It is no wonder that it has always been difficult to discern other hands in a masterpiece, especially when, as in the case of Lairesse, the traces of various hands were intentionally concealed. Given the difficulty of detecting the hidden touches of different hands on canvas, this essay introduces a novel approach to acquiring insight into workshop practices. By identifying the concurrence of the variations in Lairesse’s workload and the periods when capable pupils were present in his workshop, this study adds a layer of quantitative analysis to art historical research.

During his over-thirty-year career as a painter, Lairesse produced a large number of paintings. If we calculate the surface area of his surviving paintings, it amounts to an astonishing 6.2 million square centimeters during his active years in Amsterdam from 1665 to 1689, not to mention the hundreds of etchings and drawings and a dozen copies of his paintings. Given this voluminous oeuvre, it is hard to imagine that the master did all of the work himself. It was common practice for successful master painters in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic to have their own workshop, in which pupils and assistants worked under their guidance. Lairesse was no different. Thanks to Houbraken and other biographers, we know that approximately twenty people studied or worked with Lairesse in Amsterdam.3 Previous research has only scratched the surface of Lairesse’s workshop practice, and no one has yet examined what contributions the pupils and collaborators in his studio might have made to Lairesse’s masterpieces. Admittedly, it is impossible to know exactly what they did when working on their master’s paintings. Nevertheless, one may wonder if the quantity of Lairesse’s painting production would correlate with the presence of his most capable pupils and assistants in the workshop, who were able to contribute to their master’s paintings without leaving obvious traces. In this article, I will first summarize and analyze the trends one may discern in Lairesse’s production of paintings during his Amsterdam time. Then, I will examine the biographies and oeuvre of his pupils to evaluate their competence and active period with Lairesse. Bringing together visual and biographical sources concerning Lairesse and his pupils not only helps us peek behind the closed door of Lairesse’s studio but also, and more importantly, introduces a new methodology for understanding the workshop practice of seventeenth-century Dutch artists.

Measuring Lairesse’s Painting Workload

Traditionally, an artist’s workload is measured by the number of paintings he produced. However, this is misleading, because it assumes that the quality and the effort spent on each work is relatively constant, which is often not the case. Lairesse’s paintings range from giant ceiling pieces (such as the three-part work for Andries de Graeff, measuring 450 x 620 cm; fig. 1) to the smaller, carefully rendered works (like Antiochus and Stratonice, 31 x 47 cm; fig. 2). Given the remarkable heterogeneity in Lairesse’s oeuvre, the number of paintings is not a reliable indicator for the workload. Neither is the canvas area of the paintings he produced. Generally the surface area of a painting does correlate with the labor required for its production, as illustrated by Marten Jan Bok in his analysis of history painter Adriaen van der Werff’s (1659–1722) notebook.4 But Van der Werff’s extremely refined paintings on small to medium canvases were far less various in size than Lairesse’s, and his notebook (recording his production over six years) does not mention any large decorative works, which makes Van der Werff’s account of the time he spent on his paintings hard to compare with Lairesse’s. The time required to paint, for example, the background sky in large ceiling paintings, such as the aforementioned work for De Graeff, cannot be compared to the effort Lairesse spent on a small painting like the Antiochus and Stratonice. Therefore, in order to measure the workload for Lairesse, I will categorize his painted oeuvre into three relatively homogenous groups and try to infer the workload for each group, using the number of paintings and the surface area of the paintings:

Category I (small to medium-sized collector’s paintings) is composed of finely painted kabinetstukken—rather small paintings usually populated with a significant number of small figures (the height of the figures being under ca. 50 cm) in which Lairesse displays his skills, artistry, and knowledge in the depiction of a great variety of poses, elaborate costumes, and architectural and archaeological details. The viewer has to scrutinize such paintings from quite nearby to be able to appreciate them properly. It is apparent that these kabinetstukken, from initial design to final execution, required a substantial amount of work to produce. Lairesse himself admitted that he “executed with unusual diligence” when he painted his first Antiochus and Stratonice (see fig. 2).5 This kind of small work, in which Lairesse showed off his skill, probably served some marketing purpose at the beginning of his career, since he said: “I imagined myself to be happy, when I had acquired great esteem for small scale paintings.”6 He recalled that the Antiochus and Stratonice, of circa 1673, “received exceptional praise,”7 and three years later he got a commission to paint the same subject again, for which he made a new design (fig. 3). The surface area of the new version (88.5 x 103.5 cm) is almost six times as large—as Lairesse himself remarked—but it still belongs to the category of kabinetstukken, as the size of figures and the manner of painting are consistent with the other kabinetstukken of a smaller size.8 Upon taking a closer look at the thoughtful composition, the careful arrangement of light, the complex architectural construction, the minutely detailed metalwork, and the convincingly rendered costumes, it is hardly surprising that the new version was “being judged as incomparably better for its invention and rendering of emotions than the preceding one.”9 Paintings in this category must have been intended to spread the artist’s fame and solicit new commissions, and it is unlikely that his pupils or assistants were capable of taking part in the painting process—they were probably not allowed to do so either. Other well-known examples of this type of work include the Death of Germanicus (ca. 1670, Kassel, Museumlandschaft Hessen), the Feast of Cleopatra (ca. 1675–80, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), and Achilles Discovered Among the Daughters of Lycomedes (ca. 1685, Stockholm, National Museum).

Category II (large collector’s paintings) contains paintings of a larger format than the kabinetstukken with larger figures (the height of foreground figures in standing pose ranging from ca. 50 cm up to 1 m) that are a bit less minutely detailed than those in Category I but which were still made for the art collections of liefhebbers. In general, these were probably not meant to be fixed in the paneling of the room, though some of them might have been intended as overmantle pieces. Achilles Discovered Among the Daughters of Lycomedes in the Mauritshuis (138 x 190 cm; fig. 4) is an example in this group. For the same reason as cited for Category I, Lairesse’s large collector’s paintings would have been mostly from the master’s own hand.

Category III (decorative paintings) includes rather large to very large works, with figures ranging from a bit smaller than life-size, to life-size, or even over life-size (sometimes life-size half-figures). These works would have been fixed in the paneling of a room in most cases; the category includes ceiling paintings, painted kamerschilderingen (wall hangings), large grisaille paintings (fake bas-reliefs), and large portraits. In addition, Lairesse’s altarpieces, organ shutters, and stage scenery fall into this category. Paintings in Category III are often painted more broadly, as they would have been seen from some distance. In the biographies of some of Lairesse’s pupils, Houbraken often recalled that they worked on ceilings and interior decorations with their master. Given the broader manner of these decorative paintings and the sheer amount of labor involved, Houbraken’s words seem to substantiate that pupils and assistants mostly took part in paintings of Category III, a situation on which I will elaborate later.

This method of categorization was applied to Lairesse’s painted oeuvre, based on the surviving works mentioned in Alain Roy’s monograph (1992), its addition (2004), and the recent exhibition catalogue Eindelijk! De Lairesse (2016). The number of paintings and the total areas in each category is summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1. Statistics of Lairesse's painting oeuvre | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Number of Paintings | Area (cm²) | Average width x length | Average number of foreground figures |

| I: Collectors S/M | 58 | 331,628 | 63 x 83 cm | 6.0 |

| II: Collector's L | 50 | 855,941 | 113 x 141 cm | 5.7 * |

| III: Decorative: | 81 | 4,989,980 | 254 x 363 cm | 4.1 |

| Ceiling | 7 | 1,950,164 | 451 x 614 cm | 5.7 |

| Wall hanging | 41 | 1,213,374 | 167 x 216 cm | 4.0 |

| Grisaille | 25 | 1,003,412 | 149 x 263 cm | 3.1 |

| Altarpiece | 8 | 823,029 | 250 x 359 cm | 7.6 |

| *Portraits are excluded in the calculation for the average number of figures. If included, the average number of foreground figure is 5.1 for collector’s large-size works. | ||||

The number of figures in the foreground for each surviving painting were counted, showing hat the kabinetstukken are more elaborate, with a larger number of figures than the rest. Similar observations also apply to the architectural settings—complicated interiors, especially those with complex linear or curved architecture, which requires extraordinary skill in perspective and lighting, appear exclusively in Categories I and II, which is consistent with the conjecture that only Lairesse could have painted these works. Furthermore, paintings for collectors, although relatively smaller in size, probably took no less time than the larger decorative works in Category III. Therefore, it makes sense to plot Lairesse’s production trend by category, as measured by total canvas sizes, as an indication of his workload, and to avoid cross-categorical comparisons when assessing the variation of Lairesse’s production over time.

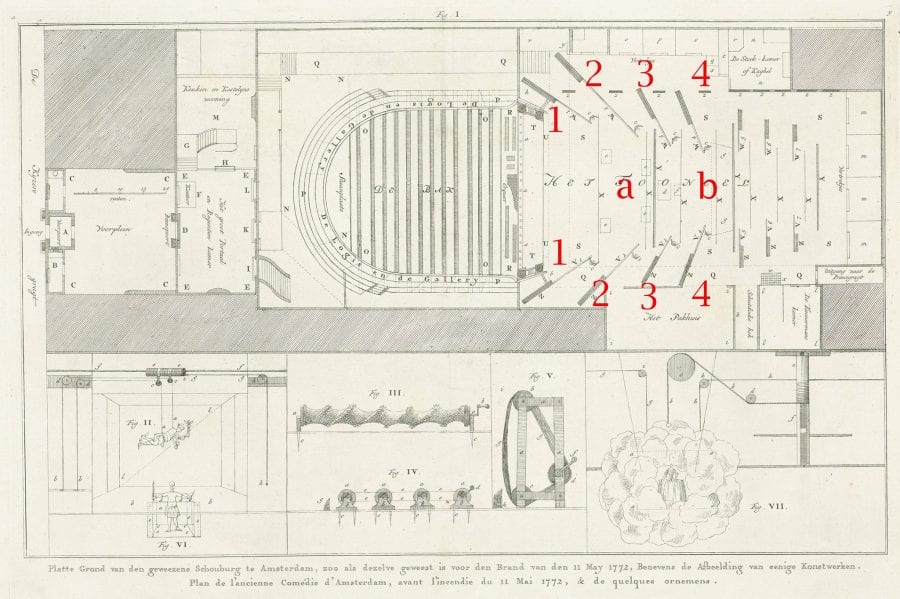

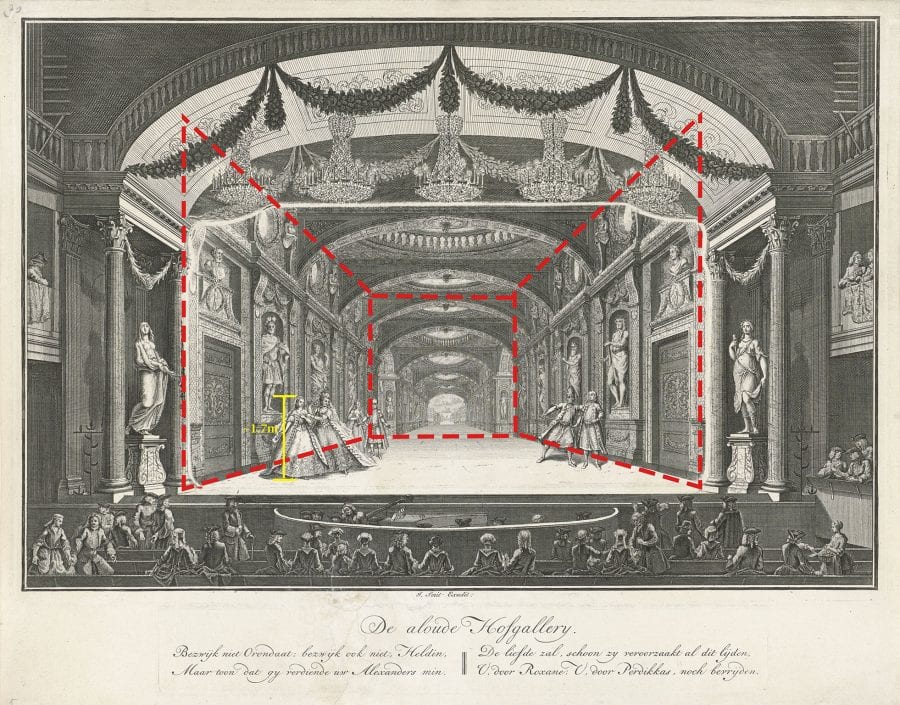

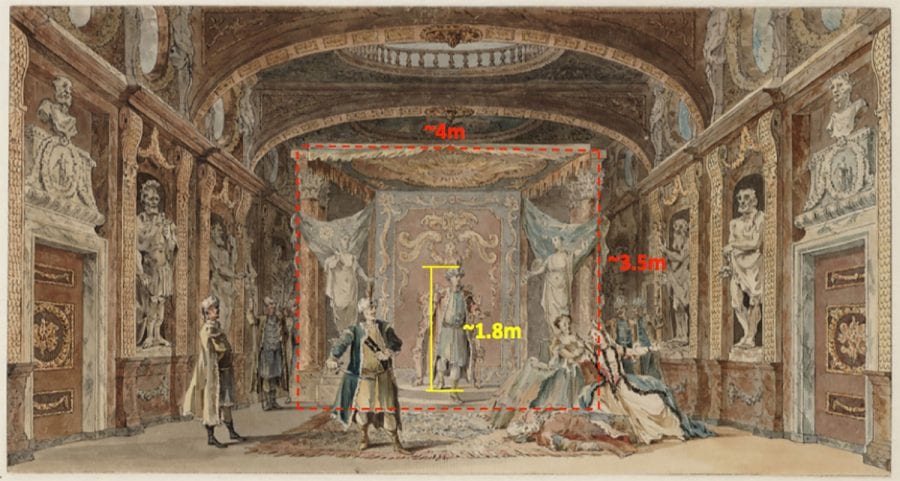

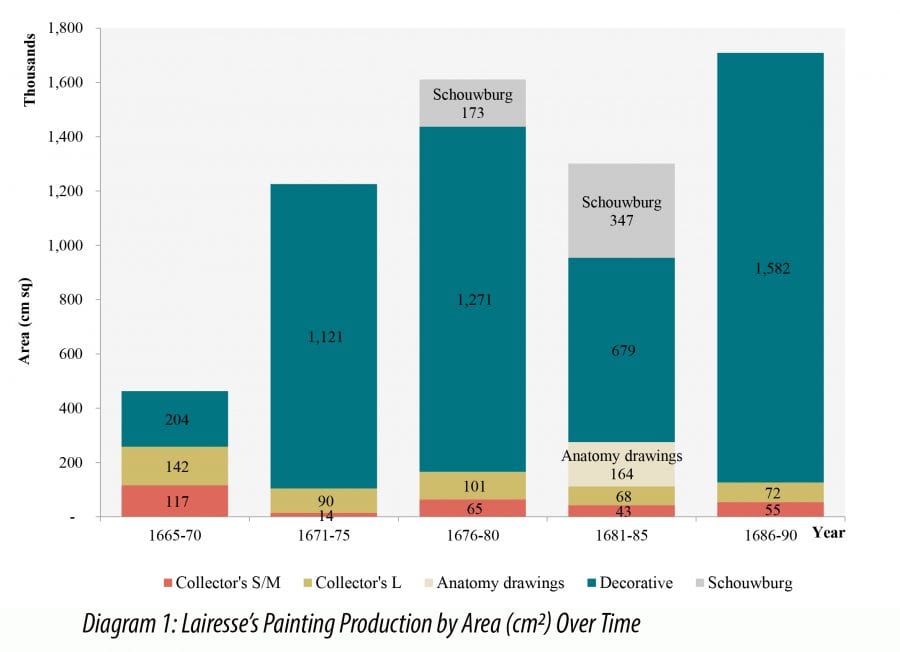

Diagram 1 shows Lairesse’s painting workload measured by his paintings’ surface area (per the three categories outlined above) over time, separated into five-year intervals in order to minimize the bias introduced by the approximate dates used in the aforementioned sources, as most dates point to a certain five-year period (e.g., ca.1665–70). I also made an estimation of the now-lost decoration of the Schouwburg in Amsterdam (Appendix I), based on a drawing of the Aloude Hofgallery in the Schouwburg before its destruction in 1772 (fig. 5). Here we can see the coulissen with eight larger-than-life fake bas-reliefs in grisaille (similar to those in the Rijksmuseum), which are the moving side wings for stage sets, probably made by Lairesse.10 In addition, as Nicolette Sluijter-Seijffert has noted, the “Koninklyke Troon” known from Reinier Vinkeles’s print is also likely by Lairesse’s hand.11 Judging from the print, the side wings and the illusionary backboard made the Schouwburg commission almost on a par with the commission from the Soestdijk Palace, as measured by canvas size.

Diagram 1 shows that, for the first five years of his Amsterdam period (1665–70), Lairesse painted many kabinetstukken and few decorative works. Clearly as a young master in a new city, Lairesse tried to establish himself through these rather small- and medium-sized, finely painted kabinetstukken, and tried to obtain larger commissions as well.12 For the first few years after settling in Amsterdam, he seems to have not yet established a workshop since his production was relatively low. Also, his first known pupil, Zacharias Webber (1644–1696), would not have arrived before 1670. Therefore, Lairesse mostly likely painted the works before 1670 all by himself, which is further supported by the fact that there are no high-quality copies known for works created during this phase.13 Therefore the workload in those years can serve as a baseline for evaluating the amount of work he could handle on his own. In the next period, 1671–75, his production of decorative works surged while the number of his fine paintings plummeted—Lairesse seems to have been overwhelmed by large decorative commissions and had to trade away his time for kabinetstukken in favor of decorative works. However, from 1676 onward, while his decorative production remained at a high level, his production of finely painted works began to pick up again. During the period 1676–80, while he painted large paintings six times as much as he had in 1665–70 (measured by area), his collector’s works amounted to 80 percent of his production of this type of work between 1665 and 1670. It seems impossible for the master to have painted everything himself throughout these prolific years. Who could have helped Lairesse between 1670 and 1690?

Artists and Draftsmen Around Lairesse

There are around twenty people known to have studied or worked with Lairesse in Amsterdam, but not all of them were qualified to take part in Lairesse’s paintings.14 To filter out the qualified pupil/assistants from this group, I traced each individual’s active periods in their master’s workshop and the contemporary views on their independent work. I also evaluated each known pupil’s capabilities and qualifications, as judged by their independent oeuvre, and screened out pupils who would not have been qualified to assist Lairesse in his commissions. For example, some pupils came to Lairesse to learn drawing or etching, such as Gilliam van der Gouwen (1657–after 1720), Bonaventura van Overbeek (1660–1705), Cornelis Huyberts (1669–1712), Jan Goeree (1670–1731), and Jacobus Boelens (life dates unknown). Judging by their surviving oeuvre and biographies, these artists later became master draftsmen or engravers and often made title pages for Lairesse’s books.15 It is worth noting that Johan van Gool records that Lairesse took Bonaventura van Overbeek into his home when the latter came back from his first visit to Italy in 1680 and that Lairesse studied the drawings, plasters, and casts Van Overbeek brought back from Italy.16 However, Van Gool does not mention whether Van Overbeek worked with/for Lairesse. Moreover, it is unlikely that he was capable of helping the master with paintings, since Van Overbeek still needed help to paint watercolors after he left Lairesse.17 The same suspicion also applies to Albert Spiers (1665–1718), who, according to Van Gool, studied the basics of painting with Lairesse. As a young pupil just starting to learn the art of painting, he was not qualified to take part in his master’s work.18 Jan Wandelaar (1692–1759) and Louis Fabritius Dubourg (1693–1775) have to be excluded: although they have been mentioned as Lairesse’s pupils, they were born after the master went blind.19

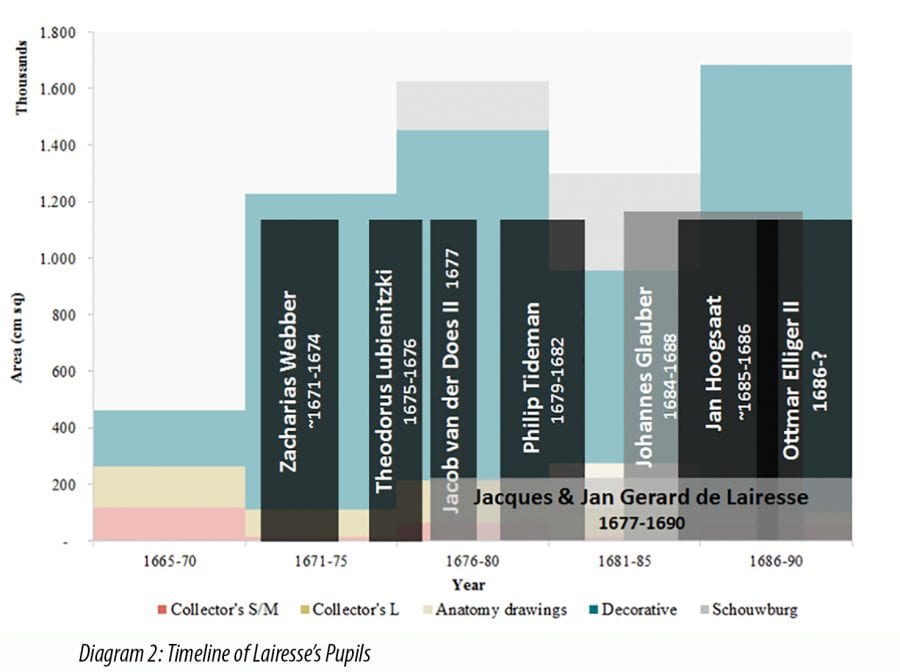

There are six pupils/assistants who are candidates for the extra hands behind the masterpieces, together with Lairesse’s two brothers, Jacques (1645–1690) and Jan Gerard de Lairesse (1651–1724), and his two sons, Abraham (1670–1727) and Johannes de Lairesse (1673–1748). Biographies of these artists from various sources have been scrutinized and, in the following sections, I will situate the pupil’s training period in their master’s career timeline (diagram 2) and look into the pupils’ oeuvre to suggest the possible roles they may have had in Lairesse’s workshop, based on their capacities, as revealed in their own works.

1671–1675: A Rising Star with an Emerging Studio

In 1672, after having “acquired great esteem for small-scale paintings,”20 Lairesse had become “so popular that everybody aspires to own his work,” according to the chronicler Louis Abry (1643–1720), a pupil of Lairesse’s father.21 Abry’s words tally with Lairesse’s first major decorative work in 1672, commissioned by the Amsterdam regent Andries de Graeff for his residence in Amsterdam. After 1670, Lairesse was frequently hired to adorn the homes of wealthy Amsterdam merchants and public buildings such as the Leprozenhuis with lavish ceilings and wall paintings. Diagram 1 shows an increase of his painting production after 1670, indicating that Lairesse must have established his own studio during this period and hired capable assistants to help with the inflow of large commissions. However, when the surge in his total painting production is examined closely it proves to be mainly composed of decorative works, while the production of kabinetstukken in this period actually plunged (see diagram 1). Lairesse, to a large extent, had given up making fine paintings to be able to finish commissions of large decorative works. This trade-off of kabinetstukken for decorative works suggests that even though the master had attracted pupils/assistants, his workshop was still short of good painters to share the load of large commissions.

This hypothesis is supported by the entry of Lairesse’s first known pupil, Zacharias Webber (1644–1696), into the master’s workshop around 1671. He was the only qualified assistant Lairesse had at that time. Webber would have worked as a skilled assistant since he had been fully trained: he was already in his late twenties and had registered as a master painter in the Guild of St. Luke in 1668–69 in Middelburg.22 After his return to Amsterdam, where he married in 1671, he worked for Lairesse on decorative works and learned the techniques of ceiling paintings, which Lairesse had developed in 1668.23 We can observe the traces of this training in Webber’s own ceiling piece with grisailles at Herengracht 512, of an unknown date, which is of a decent quality (fig. 6). Webber’s training with Lairesse may have been short; but the latter’s influence can be observed in a signed work of 1672 (fig. 7), the composition of which recalls Lairesse’s Allegory of the Peace of Breda (1667, The Hague, Gemeentemuseum). Webber was probably a strong hand behind Lairesse’s production growth after 1670. He may still have been working as Lairesse’s assistant after 1672, as he did not yet have enough commissions for himself in the early period of his career.

Judging from Webber’s own decorative works, he was qualified as an assistant by Lairesse’s standard: “he [a skillful helper] has to be well-versed in perspective, color, and the handling of the brush. With perspective we mean that he has to adapt the strength of his colors to the style of the inventor; the same applies for the purity of the colors, as well as the style or the brush stroke. All things should harmonize with each other.”24 Webber would later specialize in portraits; his first portrait design (for Johannes Erasmus Blum) is dated 1674 and is known from a print by Jan de Visscher.25 Therefore, Webber may have stopped assisting Lairesse before 1675. Besides Webber, during the period 1671–75, no other pupils or assistants are mentioned by any biographers, corroborating the hypothesis that Lairesse did not get sufficient assistance and was overwhelmed by the large commissions, such as the ceilings for the Leprozenhuis, which left him little time to make fine paintings.

1676–1680: Prolific Years with an Established Workshop

Lairesse’s career during the years from 1675 to 1680 was filled with important commissions: decoration for the Soestdijk Palace, for two houses of the De Flines family, and the now-lost stage sets for the Amsterdam Schouwburg. Assuming the Schouwburg commission was no smaller than the Soestdijk commission, Lairesse’s production during this period had reached new heights. It seems that, during this time, Lairesse had started to attract more talented painters to his workshop as he managed to produce a greater number of decorative works while also increasing his production of kabinetstukken (see diagram 1).

Theodor Lubienitzki (1653–1726) from Poland was one of the talented painters attracted to the master’s workshop. When Theodor and his brother Christoffel Lubienitzki (1660–1728) moved to Amsterdam in 1675 after their training with Jurian Stur in Hamburg, Theodor went to study with Gerard de Lairesse for about two years and might have assisted him in finishing the aforementioned Leprozenhuis project, which has a total canvas size of around 5.5 by 5.6 meters (now in Amsterdam Museum), and probably another the Allegory of Aurora, measuring 3 by 7 meters (now in Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam).26 According to Arnold Houbraken, Lubienitzki studied Lairesse’s handling so well that “it became visible in all his work,”27 a point later repeated by Jacob Weyerman, who says that people appreciated Lubienitzki’s works for their similarity to the manner of Lairesse.28 This is confirmed by observation of Theodor’s work dated around 1680s (fig. 8). Lubienitzki enjoyed his own success in Amsterdam until he was hired by the Grand Duke of Tuscany.29 In 1676, he was still in Lairesse’s workshop when the master started one of his largest and most prestigious commissions—the Soestdijk Palace decorations, commissioned by Stadholder Willem III of Orange. It is quite possible that Lubienitzki assisted Lairesse until his departure for Florence.30 Lubienitzki, considered a very able follower of Lairesse, is a strong candidate for being the hand behind the Soestdijk Palace pieces (fig. 9), and it is probably not by chance that high-quality copies started to appear in Lairesse’s oeuvre when Lubienitzki was working in his workshop (fig. 10).

Jacob van der Does II (1661–99/1700) was also attracted to Lairesse’s fame and came to study with him in 1677 after training with three established masters, including Caspar Netscher.31 As Houbraken reports, Van der Does was able to demonstrate his talent through his excellent design and later was introduced to the ambassador of France and moved to Paris to work for the French court.32 Unfortunately, none of his history paintings have survived for us to judge his qualifications. But in light of Houbraken’s praise, he should have been able to assist Lairesse skillfully.

Beside pupils, Lairesse’s family also came to join him in Amsterdam during this time. Gerard’s mother Catharina Taulier (?–1676) in 1676 became a member of the Walloon church to which Lairesse and his wife Maria Salme (?–1723) belonged. A year later Gerard’s two brothers, who were also painters, Jacques and Jan Gerard (Jean) de Lairesse , became members of the same church, which indicates their arrival in Amsterdam in 1677 or perhaps a bit earlier; they might have come for their mother’s funeral on October 2, 1676.33 After their arrival, the two brothers may have worked for Gerard de Lairesse. Houbraken writes that Jacques “followed his brother,” could paint everything including grisaille, and was at his best painting flowers; this is confirmed by Abry, who mentions that Jacques painted a flower piece in De Flines’s house together with Gerard’s grisailles.34 It is clear that Jacques helped Gerard de Lairesse on his interior decoration jobs and probably took on the grisaille works as well. According to Abry, Jacques was a very slow painter and could not make ends meet, which was the reason that he came to Amsterdam to join his brother. Yet Abry also notes: “I don’t know of anything significant he has produced in that great city [Amsterdam].”35 No signed works by him have been found, although the name “Jaques Larisse” appears in the Vrijceel list of the Guild of St. Luke in 1688, and he was said to have been painting till his death.36 Thus, Jacques may have been an assistant working solely for Lairesse until the former’s death in 1690.

As for Jan Gerard de Lairesse, according to Abry, he maintained his own painting style but still advanced his painting skills by imitating his brother Gerard. His asocial character made his life difficult although he was able to produce beautiful works.37 He may have worked for Lairesse to keep himself from starving; it would not have been a coincidence that he and his wife received money from the armenkas of their church, starting in 1699, for Lairesse himself struggled financially after he went blind in 1689.38 However, because of his character and his persistence in holding on to his own style, one may expect less collaboration between Jan Gerard and his older brother. After all, as quoted in the beginning of this essay, Lairesse had noted in his Schilderboek that an assistant should adapt entirely to the style of the master without revealing traces of his own style.39 Jan Gerard might have had difficulty in meeting his brother’s requirements and Lairesse, who referred to his own negative experience with assistants who were not subservient enough, was probably not willing to have the beauty of his compositions ruined by working with a difficult brother.40

The last important figure who came into Lairesse’s workshop during this period is Philip Tideman (1657–1705). As a pupil, Tideman stayed in Lairesse’s workshop for half a year in 1679. He was a very able painter; after leaving Lairesse, he soon established himself and received many commissions.41 Houbraken tells us that Lairesse himself was fond of Tideman’s work, especially his manner of painting.42 That was the reason why Lairesse, when he was overwhelmed with commissions, “lured (lokte)” Tideman back to his studio as his assistant and provided him with a room in his own house and a yearly salary. Tideman is said to have collaborated with the master on “ceiling paintings, rooms, grisailles etc. for another two years,” which corroborates our assumption that assistants mainly took part in the decorative works (category III).43 Given the timing and Houbraken’s description of Lairesse’s workload, starting around 1680 Tideman was very likely to have been called back for the Schouwburg commission, which probably lasted three years as Lairesse got four payments, totaling 733 gulden in 1680–82. This work would have overlapped with the commissions for Philip and Jacob de Flines’s houses, as well as the last stretch of the work for the Soestdijk Palace, which ended in 1682. Tideman moved out again after two years, presumably after finishing up the Amsterdam Schouwburg and the Soestdijk Palace projects, both of which ended in 1682; this fits the timeline in Houbraken’s record.44 However, Tideman and Lairesse’s working relationship seems to have lasted beyond the time of the former’s apprenticeship and these collaborations, as Tideman helped to draw the title page of Lairesse’s Schilderboek around 1702, and we know that he and the master corresponded in 1695.

Although Houbraken mentions Tideman as a popular decorative painter who had no lack of commissions, not many works survive that would enable us to judge his painting skills.45 The only remaining ceiling painting (fig. 11) shows that he was an able painter, but other works in Scotland (Hopetoun House) are very mediocre, suggesting that his manner of painting had deteriorated. Tideman left two notebooks, now in the Rijksprentenkabinet in Amsterdam, in which he kept a record of the commissions he received between 1694 and 1697. Future research into the Philip Tideman’s notebooks may provide more information about his experience working with Lairesse.46

Between 1676 and 1680 Lairesse’s studio had attracted several talented artists (Lubienitzki, 1675; Van der Does, 1677; Tideman, 1679), together with his two brothers (1677 onward). It is not unexpected that in this period, Lairesse managed to return to his kabinetstukken. His production of smaller painting reached 80 percent of the level it had been at ten years earlier, while the level of decorative production was six times as much as he had produced from 1665 to 1670, even without counting the now-lost work for the Amsterdam Schouwburg (see diagram 1). With his pupils and brothers assisting him with his large commissions, Lairesse finally had the time to refine and hone his kabinetstukken, as is attested by several gems within his oeuvre such as Cleopatra’s Banquet (fig. 12), or another version of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes (Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum), about which he wrote “I doubled [my] efforts. . . and spared myself no pains to surpass the first one.”47

1681–1685: A Drop in Production and a Transition to a Grander Studio

Major commissions begun before 1680 may have stretched into this period: the paintings for the Soestdijk Palace and the stage sets for the Amsterdam Schouwburg seem to have been completed no earlier than 1682. To my knowledge, Lairesse only took on one new interior decoration commission, for David Hompton’s house on the Keizersgracht (1682), during this period,48 and we can observe a decline in his painting production. This drop in the number of decorative works is, however, compensated for by the 105 astonishingly realistic anatomy drawings for Govert Bidloo’s book Anatomia humani corporis, published in 1685. Lairesse must have become acquainted with Bidloo through his important patron Philip de Flines, for whom Bidloo wrote several laudatory poems praising his painting collection.49 Bidloo returned to Amsterdam after getting his doctor’s title from the university of Franeker in 1682, meaning that Lairesse completed the whole set of drawing within three years (1682–85).

We can imagine that such anatomy drawings—transforming flesh, muscles, and blood into accurate drawings of the human body and its organs—require very different techniques and skills than the kind of work Lairesse was used to as a history painter. It would have been quite challenging and time-consuming for him to produce the 105 drawings within a short time. According to Abry, Lairesse made many preparatory drawings for the illustrations, which he sold after he went blind.50 These drawings well might be considered comparable to painted grisailles: as Cécile Tainturier pointed out, Lairesse signed them “G. Lairesse pinx.” (painted by G.Lairesse), instead of “delin.” (drawn by).51

The works carrying over from the previous period and the significant production of anatomy drawings may have kept Lairesse busy during this period. Another reason for the decreased production might be the gap after Tideman left and before he had another capable pupil joining his studio (see diagram 2). Lairesse seems to have expected to soon receive a significant amount of commissions and thus needed a sizable workshop where he and his pupils, assistants, and collaborators could work together. Therefore, in 1684, he rented a large building on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal for the large sum of 750 gulden per year.52 In the same year, Johannes Glauber came to live with Lairesse when he returned from Italy. Lairesse himself paid his contribution to the Pictura society in The Hague on December 30, 1684, probably in order to solicit the prestigious commission for the Binnenhof; this is corroborated by Abry, who says that Lairesse was called to The Hague by the Stadholder.53 It is very likely that he received the Binnenhof commission soon afterward.

In summary, during 1681–85, Lairesse was busy finishing his commissions for the previous period and setting up his new studio space for incoming work. A decline in his decorative production corresponds with his labor on the anatomy drawings as well with the lack of capable pupils in those years. By the end of this period, collaborating with Johannes Glauber and assisted by his brothers in his large new studio, Lairesse was ready to embrace the climax of his career as a painter.

1686–1689: Climax Before Disaster Struck

The last period marks the pinnacle of Lairesse’s painting production (see diagram 1), which consists of three major projects: huge organ shutters for the Westerkerk in Amsterdam, three large altarpieces, The Assumption (1687), The Transfiguration (ca. 1687), and The Crucifixion (ca. 1687), and a series of large paintings for the Binnenhof in The Hague. We would expect a sizable workshop with a number of qualified assistants to support such a volume of painting production. Therefore, we would not be surprised to find quite a few artists known to us working with the master during this period. Lairesse collaborated with Johannes Glauber on interior decorations, such as the set of wall decorations (kamerschilderingen) for Jacob de Flines, and was likely still in touch with Philip Tideman on some discrete tasks. In 1686, Ottmar Elliger II (1666–1732) also joined Lairesse’s workshop and the two artists’ working relationship continued even after Lairesse went blind; Elliger taught Lairesse’s nephew, Abraham II, son of Jacques de Lairesse (1682–1730) the art of painting in 1701 and made the illustrations for Lairesse’s Schilderboek, published in 1707.54 Jacques and Jan Gerard de Lairesse would still have been active in their brother’s workshop; and the next generation, Abraham and Johannes de Lairesse (sixteen and thirteen years old by 1686) may also have begun to practice their art. In the last phase, Lairesse had another capable painter in his studio—Jan Hoogsaat (1654–1738). According to Houbraken, he was “one of [Lairesse’s] best pupils” and “completely imitated” his master’s manner.55 In the inscription on his self-portrait (fig. 13), Hoogsaat cited Sybrand Feitama’s laudatory poem and advertised himself as “Lairesses groote zoon.” Based on those testimonies from contemporaries, it seems that Hoogsaat served Lairesse’s prestigious clients of the latter’s late period and took over his master’s commissions after he went blind, such as the one for Willem III for Het Loo Palace and the ceiling of the Burgerzaal in the Amsterdam City Hall: it is unlikely that Hoogsaat would have received either commission without the connection with his master. Later, he worked for several esteemed burgomasters in Amsterdam, such as Jan Trip and Jan Six. This confirms his popularity, which was surely due in part to his role as Lairesse’s artistic heir.56 However, little is known about Hoogsaat’s life beyond his training with the master, except his marriage registration in 1687 in which he is recorded as a thirty-three-year-old fijnschilder.57 He was not mentioned in the Guild of St. Luke list in 1688, while the master’s earlier pupils/assistants, Zacharias Webber, Philip Tideman, Johannes Glauber, and Lairesse brothers were all mentioned.58 Presumably Hoogsaat was still working in his master’s studio. Not many of his works survive, but his known works are all dated to the eighteenth century. Apart from the self-portrait, and the large ceiling in the Burgerzaal of the City Hall (Royal Palace), there are three grisailles in Huis Nijenburg’s Blauw Kamer (fig. 14) in which Lairesse’s manner is present.

During the last years, Lairesse’s workshop must have been overwhelmed with lucrative commissions, as we may infer from a contemporary travel journal by Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin, who paid a visit to Lairesse in 1687. Tessin noted that Lairesse “was regarded among the best [painters] in Amsterdam, especially for ceiling paintings, which are very beautifully painted . . . [he] paints also very well in small [paintings],” indicating that Lairesse worked on large and small paintings at the same time.59 Although Tessin did not specify how Lairesse’s workshop functioned, he did mention Glauber being in Lairesse’s studio and noted their collaborative work, with life-size figures filled in by Lairesse, the rest being finished by Glauber.60 Tessin also mentioned that “particularly beautiful is the study, which is painted in a small format [suited for] the front of the city hall.”61 It is possible that Lairesse was making an oil sketch for the ceiling of the Burgerzaal that was later finished by Jan Goeree and painted by Jan Hoogsaat.62

Assisted by his capable pupils Jan Hoogsaat, Ottomar Elliger II, and Jacques and Jan Gerard de Lairesse and collaborating with Johannes Glauber, Lairesse reached the pinnacle of his painting production before the tragedy that struck in 1689 brought a sudden halt to his career as a painter. After losing his sight, Lairesse was forced to give up painting.

Conclusion

This research has introduced a new method that translates a painter’s oeuvre described in monographic catalogues into a dataset with measurable variables (date, size, figures, etc.) and visualizes the trends in the master’s production. The quantitative analysis not only facilitates observations but also provides a new perspective upon an artist’s life and work. Situating pupils’ active periods, compiled from biographical sources, into the master’s timeline and production trends can shed new light on workshop practice. The limitation of such an approach is also obvious—the quality of the production calculation is bound to the approximate date of paintings. This might introduce many uncertainties or even noise into the date-based calculation. This problem can be partially addressed by carefully choosing the time intervals that may tolerate the approximate dates, such as a five-year or ten-year interval, since most approximate dates fall in either of these two intervals. Another limitation of this approach is that it can only be applied to artists by whom a significant number of paintings are still known to us.

Fortunately, Lairesse’s surviving oeuvre is sufficient for applying such an approach. Categorizing Lairesse’s oeuvre into three relatively homogenous groups allows us to measure the master’s production of paintings over time and enables us to observe the overall trend as well as the trade-off between effort spent on the fine and the broad paintings during periods when he did not have an established studio. Through the biographies of Lairesse’s pupils, we can not only estimate the time when they might have worked in their master’s studio but also gauge what their main task would have been, namely, painting ceiling and decorative works: works belonging to Category III (decorative) are thus the most likely collective undertakings. By matching the timeline of Lairesse’s career and the presence of capable pupils in his studio, it becomes clear that production was boosted by the arrival of capable pupils and his brothers. A reduction in painting production also tallies with a transition period in Lairesse’s workshop. The process that we have described, in which the workshop participated in large-scale commissions, also explains why and when the master had more time for making collector’s paintings by himself. In other words, the flow of Lairesse’s painting production correlates with the number and the quality of pupils and assistants in his workshop.