The essay signals considerable gaps in the current state of research on Lairesse’s drawings, concerning attribution, supposed function, relation to the artist’s painted and printed oeuvre, and (the lack of a) general overview. Taking the pioneering catalogue of Alain Roy of 1992 as its basic starting point, the essay chronologically follows publications on the subject over the last decades. By addressing conflicting interpretations, asking critical questions, and adding new or scarcely considered material to the works discussed in these publications, the essay hopes to reveal the problems surrounding this complicated topic and generate scholarly discussion.

Gerard de Lairesse was, after Rembrandt and possibly Abraham Bloemaert, the most wide-ranging artist active in the Northern Netherlands during the seventeenth century. His subjects cover history, allegory, portraiture, and even genre. Moreover, Lairesse was prolific in all three major pictorial media of his time. In addition to a known painted oeuvre of more than 250 works, often in large format, he produced some 120 prints himself and collaborated with various printmakers who produced many prints after his designs. And—of special interest here—he left us a large number of drawings. In 1992 Alain Roy was the first to compile this impressive oeuvre. More than a quarter-century after its publication, his monograph with catalogue raisonné is still the authoritative work on the artist, a milestone in Lairesse research.1 A near quarter-century later, in September 2016, the first monographic exhibition on Lairesse, Eindelijk! De Lairesse, opened at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede. In addition to a large number of paintings and prints, the exhibition included twenty-seven drawings. Five of these, however, were not accepted by Roy; one was unknown to him; and one was disputed by other scholars.2 Considering that sixteen of these drawings belonged to two commissioned cycles, it follows that only four individual drawings shown in Enschede have been generally accepted.3 This discrepancy is symptomatic of the lack of scholarly consensus. Surveying the literature on Lairesse’s drawings, one is struck by the severely unfinished status of research on the artist’s drawn oeuvre.

When preparing the exhibition and during its aftermath, I tried to gain an overview of the drawings identified as “Lairesse” in museum collections, print cabinets, private collections, auctions, and the art trade. What I encountered is a mer à boire of possible Lairesse drawings, some of which have been rejected by Roy, while others have never been taken into consideration before, or hardly so, and certainly not in publications. My contribution here should be considered a first foray into this vast number of possible Lairesse drawings. The essay intends to share the complexities and uncertainties that I ran into. By following chronologically the handful of publications on Lairesse’s drawings that have appeared over the last thirty years, and by adding related drawings and new attributions to the works discussed in these publications, I hope to disclose problems and gaps, to quantify Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre, and to uncover production patterns (as far as these are recognizable). Thus the essay raises questions and, in certain cases, provides possible answers. First I will discuss Roy’s catalogue of drawings; after that, the publications on Lairesse’s drawings by Janno van Tatenhove, Erwin Pokorny, and Annemarie Stefes will provide further guidelines.

Roy’s Drawings Catalogue: Precious but Problematic

Alain Roy’s book focuses mainly on Lairesse’s paintings. Indeed, the works he grouped together (P[einture].1–221) still comprise, to a large extent, what we understand to be the artist’s painted legacy.4 In addition to the catalogue of paintings, Roy’s work also contains overviews of Lairesse’s prints and drawings. For the prints, he could rely on Jan Timmers’s 1942 dissertation on the subject.5 Typical for the book’s emphasis, the prints (G[ravure].1–117) are discussed in relation to the painted oeuvre wherever applicable; thus, although they are numbered independently, they are subordinately dispersed throughout the paintings catalogue. The remaining group—prints not related to paintings—is listed separately. With regard to Lairesse’s drawings, however, the author could not rely on previous compilations. Admirably, he was able to bring together a group of no less than 186 drawings that he accepted (D[essin].1–185)6 and an even more substantial list of 211 rejected ones (D[essin].R[ejectée].1–211). In the following, I will refer to Lairesse’s works, where needed and/or possible, with Roy’s numbering.

The only overview to date, Roy’s drawings catalogue, though pioneering, was not the primary goal of his undertaking. In fact, he admits that Lairesse’s drawings are, in his view, “le plus grande énigme de son oeuvre.”7 Roy summarily analyzes size, technique, and material and does not discuss the remarkable differences among these within Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre. In structuring his catalogue, Roy makes choices that are—understandably—geared towards his discussion of the paintings but are consequently confusing for the drawings. Wherever possible, the drawings, like the prints, are listed within the paintings catalogue, while the remaining accepted drawings are listed separately. The catalogue of 211 rejected drawings, located in the back of the book, is, for obvious reasons, only incidentally illustrated. It consists of several categories, followed after D.R.104 by a summary list of 107 remaining drawings (“Dessins de qualité médiocre et/ou sans aucun rapport avec le style de Lairesse”), organized alphabetically by collection.8 The absence of drawings (be it under the D. or the D.R. category) from collections that are represented with other drawings forms a complication. It is not just the more obscure collections that have fallen victim to this. It is also the case with major collections such as the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, the Bremen Kunsthalle, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, the Rijksmuseum, and the British Museum: all hold drawings of interest that are missing from Roy’s catalogue, while other drawings from these institutions (accepted and/or rejected) are included. A further problem for gaining insight into Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre is Roy’s treatment of the numerous red chalk drawings done in preparation for or after paintings or prints. Roy does not accept these, but he does not list them among the rejected drawings either. Instead, they are mentioned as “Oeuvres en rapport” (compositionally related works) under the entry of the relevant painting or print; thus, these important drawings are denied a place among either Lairesse’s accepted or rejected oeuvre.9 All in all, the fact that more than four hundred drawings are dispersed over various locations throughout the book, often without an image, impedes the book’s functionality as an overview of Lairesse’s drawings. Moreover, the oeuvre presented appears to be far from complete.

Roy made a selection of 186 accepted drawings, but we should be aware that no less than 106 of the 186 drawings belong to a splendid, but not necessarily representative group that Lairesse was commissioned to execute for Govert Bidloo, in preparation for the engravings for the latter’s anatomy book Anatomia Hvmani Corporis (1685).10 Spectacular as they are, the Bidloo drawings remain very much a group in themselves, bearing only a modest relation to most other drawings by the artist. The same can be said about a group of seven drawings commissioned by the overlords of the city’s Leper house (Leprozenhuis).11 Although these bear a certain stylistic resemblance to the Bidloo group, Lairesse’s goal was decisively different; they were to be bound into an album as finished works of art. Leaving the drawings that belong to these two specific cycles outside our scope for a moment, and considering, further, that Roy also lists thirty-five “ghost” drawings—drawings he assumes to have once existed on the basis of captions underneath prints mentioning Lairesse as the designer—the number of attributed drawings that initially seemed so impressive has shrunk to a mere thirty-eight. And in this group, some attributions have been questioned by other scholars.12

These thirty-eight drawings differ significantly in size, material, technique, presumed function, and ambition. Twenty of the drawings can be related to a print, but it is difficult to discern a method in Lairesse’s approach to them. Some are unassuming sketches, done with a pen and brown ink in a scratchy, informal style (e.g. D.3–5), or wash drawings overlaid with a grid (D.10). Others are fully developed, complex compositions in black chalk, pen, and gray wash (D.10) or neatly executed but small head studies with red and black chalk (D.2, 19). In contrast, the eight drawings that can be related to paintings show more cohesion. Almost all of them are more or less quickly sketched, admirably efficient composition drawings done with brown or black pen and extensively washed with gray or brown (D.1, 8, 15, 21, 50, 158, 169).13 Moreover, all of them are of a substantial and more or less similar size, most of them measuring about 25–30 x 37–45 cm. Tellingly, of the 186 drawings attributed to Lairesse by Roy, only twenty-six (14%) cannot be related to a print or painting (this significant pattern remains largely intact in the following analysis).14 Excluding the two commissioned cycles, twelve drawings remain that have no connection to prints or paintings (of thirty-eight, raising the percentage to 32%). They constitute an inconsistent group of varying efforts, such as a disputed self-portrait (D.2), a minor pen sketch for a map cartouche (D.12), a finished study in gray wash over a red chalk design (D.46), a sketch in brown with brown wash of a collector in his study (D.24), and a large design for a chandelier for the theatre (D.170). Because of the limited volume of independent autograph drawings and the relative lack of cohesion within this small group (concerning function, technique, and method), Lairesse’s profile as a draftsman does not emerge as clearly as one would hope.

Red Chalk Drawings and Preparations for Frontispieces

In the years following Roy’s publication, several authors have added to Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre. They have done so in the periodical Delineavit et Sculpsit in particular. By 1989, the curator of the Leiden University print room, Janno van Tatenhove (then under the pseudonym Paula Wunderbar), focused attention on two large, signed drawings—one in Edinburgh, the other in Porto—which were later identified as important studies for the large organ shutters in the Amsterdam Westerkerk.15 In subsequent contributions, called “Lairessiana,” Van Tatenhove continued to add—in a pars pro toto fashion—to Lairesse’s drawn and printed oeuvre. Over the years 1993–2000, he and his students convincingly attributed (and re-attributed) another eleven drawings.16 Significantly, only two of these thirteen drawings in total could not be linked to paintings or prints, again underlining the strong interdependency among these distinct parts of Lairesse’s oeuvre.

Van Tatenhove’s reconsideration of the red chalk drawings was one of his most important Lairesse contributions. As he observed, Roy dismissed or omitted the majority of such drawings (“les feuilles à la sanguine sont très rares, sans doute parce que cette technique semblait à Lairesse manquer de force et de precision”17), accepting only three, none of them very elaborate: the (by some) questionable Self Portrait in Berlin, executed half in red chalk, half in black (D.2); the powerful yet relatively unassuming Study of Three Heads in the Rijksmuseum (D.19); and a preparatory drawing for a title print (D.44).Van Tatenhove, “Lairessiana II,” 39.18 Noting that “research into this field [of red chalk drawings] is still waiting to take off,” Van Tatenhove foregrounded three virtuoso red chalk drawings—Father Time, Safety (both Louvre) and Freedom of Trade (Amsterdam, Stadsarchief). The first two had previously been accepted as autograph drawings by Frits Lugt (Father Time, Safety) and Derk Snoep (Safety); the third was a new addition.19 Whereas Snoep considered Safety Lairesse’s preparatory drawing for one part of his 1672 ceiling for the Amsterdam burgomaster Andries de Graeff’s house, Roy (“oeuvres en rapport,” under P.68, 156) regarded both Father Time and Safety to be drawn by Johannes Glauber, as preparations for the prints that Glauber executed after the De Graeff ceilings and after Lairesse’s now-lost painting of Father Time. Van Tatenhove, then, in part followed Roy’s conclusion that the drawings are preparations for Glauber’s prints (including Freedom of Trade, which resembles the composition of another part of the De Graeff ceiling), but in contrast attributed them to Lairesse himself. To support his attribution, he rightly pointed to the captions underneath all three prints, which explicitly state that “G. Lairesse Pinx. et Del.” (in that sequence: he painted it, and then made a drawing of it). This straightforward notion that Lairesse himself executed these red chalk drawings—in this case as an in-between step from painting to print—opens up a whole field of possible Lairesse drawings that are not included in Roy’s catalogue and provides a welcome insight into Lairesse’s working process. Following Van Tatenhove’s argumentation, all three drawings were shown in Enschede as works by Lairesse.20

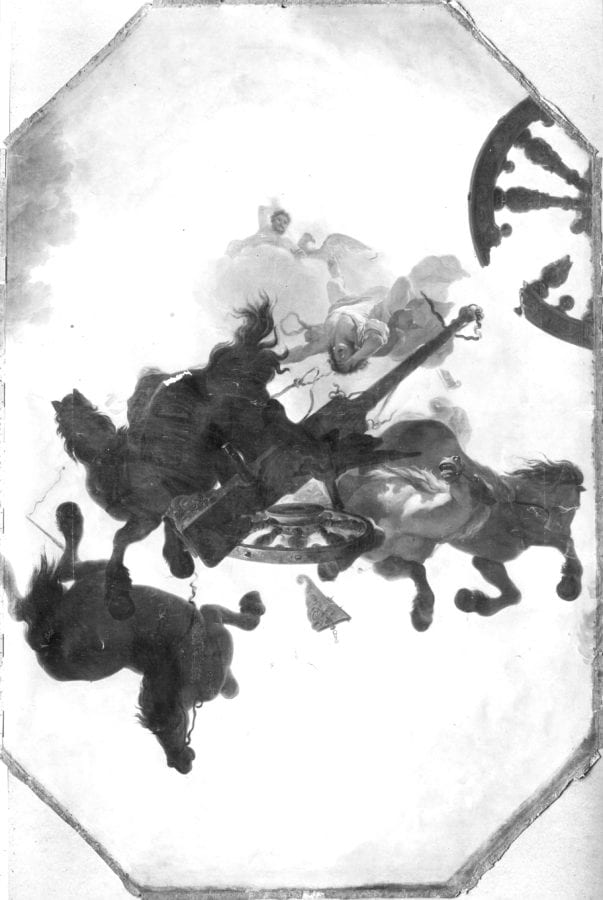

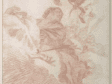

Whereas Safety and Freedom of Trade thus followed, rather than preceded, the ceiling they relate to, another drawing does the opposite. The Fall of Phaeton in the Louvre (fig. 1), executed with brown wash over a red chalk tracing and already suspected by Roy to be a ceiling study (D.32), was indeed done in preparation for a long-overlooked, now-lost, three-segmented ceiling, of which, until recently, only one part was known through a reproductive engraving by Glauber (see P.70). This ceiling, first published in the Enschede exhibition catalogue by Margriet Eikema Hommes and Tatjana van Run and only known through black-and-white images (fig. 2), shows, as the authors correctly note, the exact same composition as the drawing.21 Another drawing in the Louvre, in fine red chalk and comparable in execution to Safety and Freedom of Trade, shows a little Cupid and a divine duo in the clouds, presumably Mars (recognizable from his spear) and Venus (fig. 3), seen in another section of the same ceiling (fig. 4). Although the drawing was rejected by Roy (D.R.195), the hitherto unnoticed relation with the ceiling calls for its inclusion in Lairesse’s oeuvre. Yet unlike the drawing, the ceiling shows another group of gods—Jupiter, his eagle, and Minerva—in between Cupid (above) and Venus and Mars (below). This seems to imply that the same fine red chalk technique was used differently here: not in preparation for a print after a more or less finished composition, but as a step in the creative process.

Such refined partial studies in red chalk, done in preparation for paintings, are rare. Yet another possible example is found in the Rijksmuseum: a study of two female allegorical figures, Fortitudo and Asia (fig. 5). These figures are found in Lairesse’s Europe, Africa, and Asia Pay Tribute to the Wealth of Rome, a large painting last seen in Copenhagen in 1937 (P.65). In addition to the Rijksmuseum drawing and the painting, there is also a preparatory sketch in pen and brown wash in the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett (D.21), on which the names of the figures are written. Roy lists the Rijksmuseum drawing under the Copenhagen painting as an “oeuvre en rapport,” a copy after the painting. However, the drawing’s refined technique—akin to that of Father Time—argues against a later copy. Rather, it seems to be an autograph second step—following the Berlin sketch—in the process of working towards the finished painting.22 Moreover, the figures in the painting deviate from those in the drawing in details, such as Fortitudo’s neckline and Asia’s headgear, again pointing to a creative drawing, rather than a copy. A third option, the drawing being a ricordo, meant as an aide-memoire, cannot be excluded. But it seems less likely, not only because of the deviations but also considering the positions of the figures to one another, which do not match those in the painting.

Van Tatenhove also discussed a number of studies for frontispieces, and through a specific example—a preparatory drawing for Lairesse’s frontispiece of Signorum Veterum Icones, a volume of prints after the sculpture collection of Gerard Reynst, published in 1671 (G.66)—was able to expose how Lairesse proceeded step-by-step.23 A rough pen sketch for this frontispiece in Brussels was already known (D.22), but Van Tatenhove focused attention on a larger and much more finished red chalk drawing of the same composition, clearly the final study for the same frontispiece. A rare example in which more than one preparatory drawing is still extant (as enthusiastically noted by Van Tatenhove), such a case helps our insight into Lairesse’s process of working towards a finished print. Although not completely analogous, more examples can be considered. Comparable, for instance (although not resulting in a print by Lairesse himself), is a hitherto-overlooked study for the title print of P. C. Hooft’s Nederlandsche Historien, engraved by Johan van Munnickhuysen. Lairesse’s final red chalk drawing in a Paris private collection was already known (D.44), but his preliminary pen sketch for this print, executed in a rather scratchy technique that he used most often in preparation for prints (see below for a discussion of several examples), and preceding the Paris drawing, is in the Bremen Kunsthalle (fig. 6).

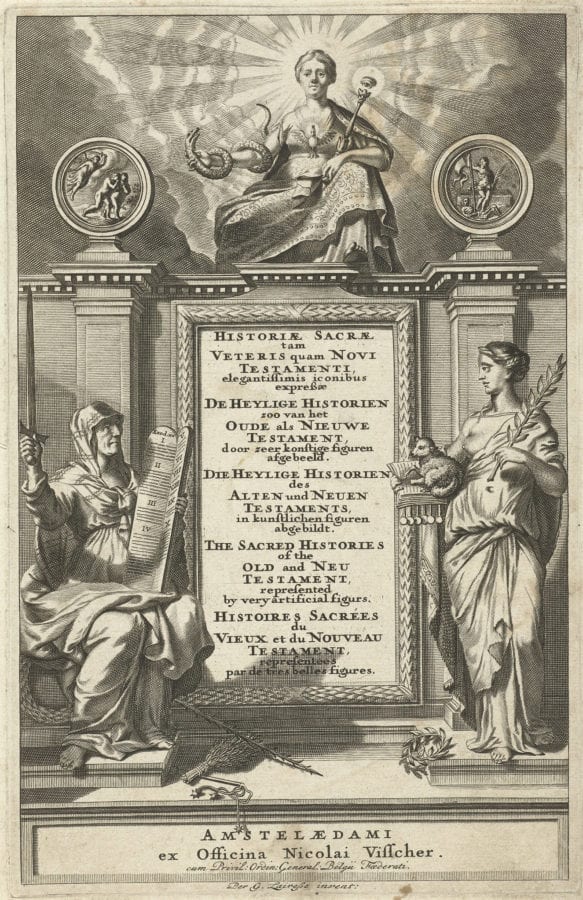

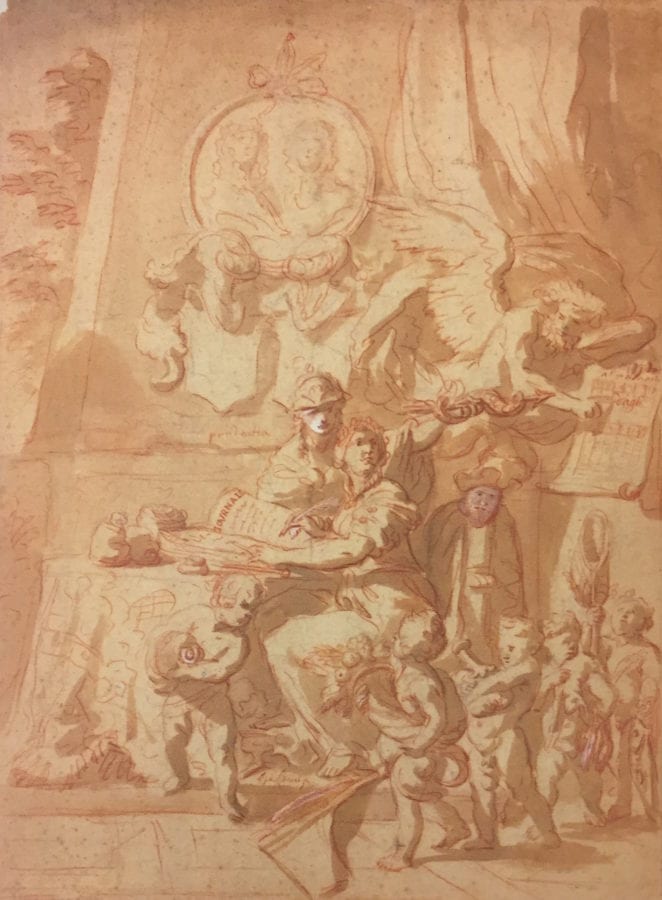

That Lairesse did not always apply the same technique for such initial sketches becomes clear from a recently surfaced study for a frontispiece, in the Museum Flehite in Amersfoort (fig. 7).24 This simple drawing in pen and brown wash, which served as the template for the frontispiece of Historiae Sacrae tam Veteris quam Novi Testamenti, probably engraved by Abraham de Blois and published by Nicolaes Visscher (fig. 8), recalls Lairesse’s drawings of collectors in their studies (D.24) or his sketch for the portrait of William III, also first published by Van Tatenhove.25 Moreover, the handwriting of the words “prudentia dei” underneath the central top figure is the same as that in Lairesse’s Europe, Africa, and Asia Pay Tribute to the Wealth of Rome in Berlin (D.21). A finished red chalk drawing of the composition is not known, but given the previous examples we might assume it once existed. A signed preliminary red chalk drawing in Heidelberg (D.R.78, described there as “probably inspired by a frontispiece by Adriaen van der Werff”) testifies of yet another approach (fig. 9). The sheet shows a female allegory of Trade, seated at a table with moneybags, in front of a monument with a double portrait cartouche. While keeping a journal, Trade is joined by Prudentia and a winged male figure, presumably Time. Putti with a cornucopia, a pouch, and hunting loot pay her tribute. Roy (under D.R.78) attentively notes that a red chalk drawing in the Rijksmuseum “under the name of Lairesse” mirrors the Heidelberg composition (fig. 10). The Rijksmuseum drawing, however, is of such high quality and so reminiscent of Lairesse’s vocabulary that it is no doubt by the artist himself. Unfinished, it seems to have been the next step in preparation of a (never executed) project, possibly a chimney piece, an allegorical print, or a frontispiece. As such, it was included in the Enschede exhibition.26 In 1998, the Rijksmuseum acquired a puzzling third rendering of this composition, this time in black chalk with a brown wash, but otherwise nearly identical to the Heidelberg sketch (fig. 11). Did the black chalk sketch precede the Heidelberg sheet? Is one a copy after the other by another hand (possibly that of a talented pupil) after all?27 These questions remain to be answered. In any case, these diverse works suggest that Lairesse did not always follow a steady script in preparing his work, specifically his print production.

Scratchy Sketches and Drawings for Print Series

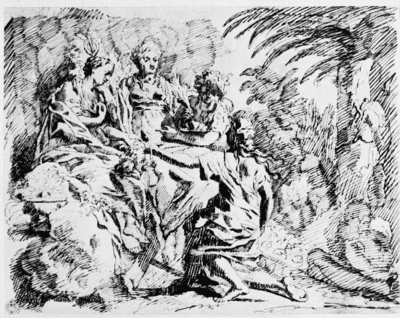

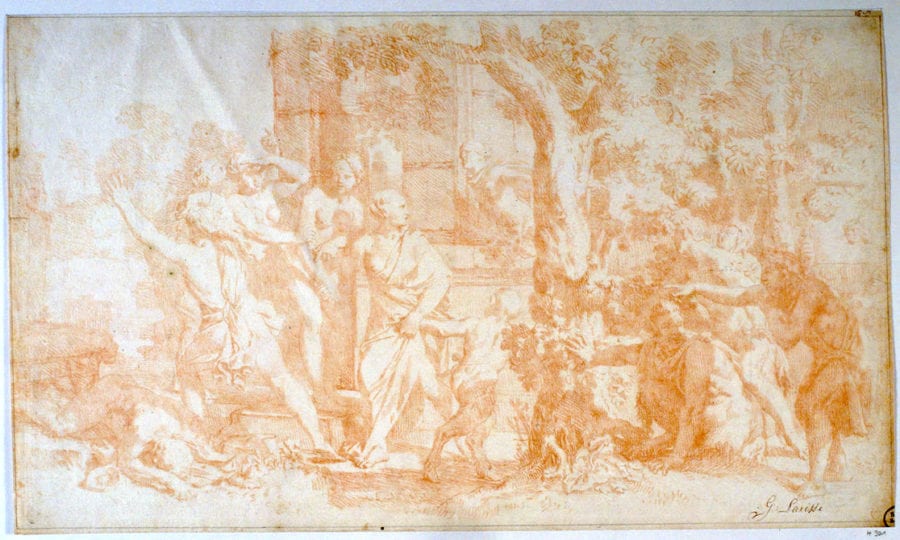

Following the first of his “Lairessiana” articles, Van Tatenhove, in a Delineavit et Sculpsit publication on the drawings in the Jean van Caloen Foundation in Kasteel Loppem near Bruges, connected two sketches in that collection with a seven-part print series executed by Lairesse himself, depicting themes from Genesis (G.2–8).28 Three sketches—two in Dusseldorf and one in Liège—were already known (D.3–5). All five are identical in size and are oriented in reverse to the prints; they also share a distinctly scratchy appearance, which is surprising but nonetheless effective. It convincingly shapes three-dimensionality in the sturdy, typical Lairessian figure types and their landscape setting. They would have been too rough as templates for another printmaker, but they were evidently suitable for Lairesse himself to work with. For someone only superficially familiar with Lairesse’s oeuvre, and unaware of the connection with Lairesse’s Genesis print series, it might be hard to believe that these sketches were done by the same hand that was also responsible for the splendid red chalk drawings. However, these drawings do not seem to be an isolated case. Another sketch in Bremen shows a barely clothed man kneeling before three women, one of whom holds a caduceus as she exchanges something for the man’s water flask. The drawing is so similar in its execution, and in its idiosyncratic employment of cross-hatching to suggest deep shadow parts, that it must be by the same hand (fig. 12). Stylistically related is another, more elaborate sketch formerly in a London collection, which seems to depict Circe Turning Odysseus’ Men into Animals (fig. 13). Marvelously dynamic, and filled with the same type of fantastic animals—dragons and three-headed lions—featured in the Father Time drawing in the Louvre, the sheet has an abundance that differs from the more straightforward Genesis group. Yet its scratchy execution is very similar. Were the Bremen and London sketches also intended as preparatory drawings for prints that Lairesse wanted to execute himself? Or, rather, were they quickly sketched ideas for history paintings?

Another biblical print series—a New Testament cycle—consists of seven prints done after Lairesse’s designs (GdL inv.) by Pieter van den Berge, who arrived in Amsterdam in 1692—two years after Lairesse turned blind—and worked there until 1737. Roy (D.36–43) lists three autograph drawings that underlie the prints, one associated drawing, and four “dessins perdus.” In stark contrast to Lairesse’s homogeneous sketches for the Genesis series, the drawings on which the New Testament series is based do not form a cohesive group at all. Apparently Van den Berge assembled them together from other projects, presumably with Lairesse’s (or his family’s) permission. The three autograph drawings listed by Roy are not only very different in size, but they also diverge significantly in technique. The Adoration of the Magi (D.38, 10.5 x 5.6 cm.) is a pen drawing with gray wash, oriented in the same direction as the print; the Temptation of Christ (D.41, 13 x 7.4 cm.), a pen drawing with brown wash squared with a red chalk grid, is also in the direction of the print; and the Resurrection (D.42, 18.6 x 11.5 cm.), done with a brush and gray wash over a red chalk outline, is in reverse to the print. An unpublished Circumcision in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, executed in a combination of techniques and oriented in the same direction as the print, was undoubtedly the example for Van den Berge’s print of the subject, which differs only in details, such as the headdress of the priest (fig. 14). Roy (D.39, “dessin perdu”) could not have known this drawing, as it only surfaced in 1995.29 A likewise unpublished Pentecost (fig. 15) in the same collection, clearly executed by the same hand, forms a pair with this Circumcision but was not engraved by Van den Berge.30 A red chalk Annunciation, listed by Roy as a reverse copy after Van den Berge’s engraving (under D.36, 19 x 11.8 cm.), of the same size as the above-mentioned Resurrection, is executed with much confidence and might well be an autograph work after all (fig. 16).

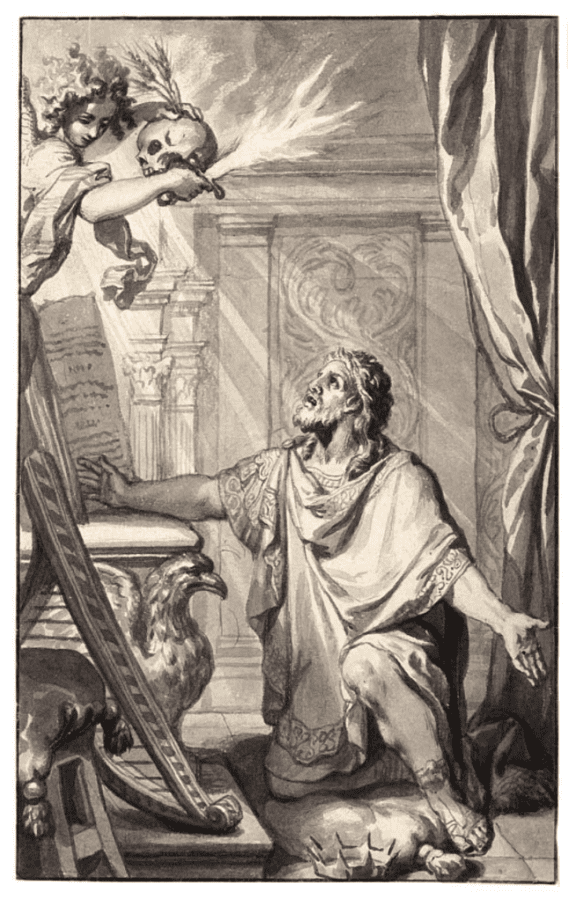

In fact, the similar-sized Annunciation and Resurrection drawings were probably part of an original project prior to Van den Berge’s assembled cycle. Leading to this idea are two other engravings after these drawings, one of which (the Annunciation) is signed by the already mentioned Johan van Munnickhuysen, Lairesse’s collaborator on several projects.31 Two more engravings seem to be part of this series as well: one after an unpublished Lairesse drawing, depicting the Adoration of the Magi in the collection of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (fig. 17), that is quite similar in conception to the drawing with the same subject used by Van den Berghe for his series (D.38); the other after Lairesse’s drawing of King David with the Angel Holding the Three Plagues, formerly in the Unicorno collection (fig. 18).32 Not only are the engravings similar in technique, size, and framing (all with a narrow double outline); the four drawings they rely on share virtually identically measurements as well, and they are executed in the same technique (gray wash over red chalk). The Adoration of the Shepherds (D.37) that Roy included in the New Testament cluster (although he could not relate it to a print by Van den Berge) seems—on the basis of its size, subject and technique—to be part of this “Munnickhuysen” group as well, although I have not found an engraving of it. Unfortunately the engraved series’ purpose—four scenes from the life of Christ, one from the Old Testament—eludes us, yet as the verso of the Resurrection contains text in book print, we may assume that it was meant as a book illustration cycle.

More Red Chalk Drawings, Mostly Connected to Paintings

In the wake of Van Tatenhove’s “Lairessiana,” other authors have come forth to disclose Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre further. Among the most important contributions is the 1998 Delineavit et Sculpsit article written by Erwin Pokorny, who discusses a group of no less than eighteen drawings attributed to Lairesse in the collection of the Vienna Albertina. Pokorny understandably expresses surprise that “although Lairesse is in no other collection, except for Amsterdam, represented so richly and with such quality, […] one searches in vain for it in Roy’s Lairesse monograph.”33

After a careful analysis, Pokorny considers eleven drawings—all of high quality, and almost all showing finished compositions—to be autograph works (Pok.1-11). Moreover, no less than eight of these are elaborate, large-format red chalk drawings (the largest measuring 48.9 x 64.3 cm.). Of these eight drawings, six can be connected to another work by or after Lairesse featuring the same composition; in five cases, that work is a painting. Does this, then, mean that Lairesse and his workshop used red chalk drawings in preparation for paintings? Not necessarily. As seen in the case of the De Graeff ceiling drawings and Father Time, fine red chalk drawings were used in preparation for prints after painted compositions, or, as is probably the case with the Cupid and Two Gods on a Cloud and the Fortitudo and Asia, they were used to prepare individual pictorial elements of a painting’s composition. The difficulty of distinguishing between the various possibilities is apparent from the first drawing discussed by Pokorny, Agamemnon Mourning Polyxena’s Sacrifice (Pok.1). This drawing shows a segment of a composition known to us through an engraving by Lairesse himself, yet a now-lost painting of it must have once existed as well, as Arnold Houbraken elaborately described it.34 Was the drawing done in preparation for the painting or—as Pokorny speculates—a partial copy of it? In the latter case, it possibly served to transfer the composition and to customize it for the engraving. The drawing’s scale, matching that of the print one-to-one, seems to support this theory. But why then was the composition not adapted as a whole? That the figure of Agamemnon was meant to be singled out for an individual print seems doubtful.35 Or is the drawing a partial copy after the print, possibly made for commercial purposes? And if so, can Lairesse still be considered to be the draftsman?

In three of the remaining four cases, a pattern emerges. The compositions of Dancing Putti near a Woman with a Triangle, of Esther Accusing Haman before Ahasuerus, and of Women and Putti at the Grave of the Poet Eumolpos all exist in three media: as elaborate red chalk drawings (Pok.2, 4, 8), as paintings (P.47, 98, 184), and as prints (under P.47, 98, 184). In all three cases, painting, drawing, and print share the same orientation; another printmaker was responsible for the print; and the red chalk drawing matches the size of the print. Notably, this last point also applies to the aforementioned Father Time, Safety, and Freedom of Trade. It thus seems to add to the suggestion that in Lairesse’s workshop elaborate red chalk drawings functioned as scale-fixed examples for prints, either as an intermediary stage from painting to print, or possibly also as the final example for both (as Pokorny suggests).36

Still, one should not jump to conclusions too easily. Two of the three prints mentioned (Esther and Eumolpos) were engraved by Pieter van den Berge, who, as we have seen, arrived in Amsterdam in 1692, two years after Lairesse turned blind, and worked there until his death in 1737. If the red chalk drawings of these subjects are really by Lairesse—and we assume they are because of their evident connection with Lairesse’s painted oeuvre, their quality, and their stylistic overlap with other red chalk drawings presumably by Lairesse—then it follows that they were certainly not made in preparation for these prints. Rather, they were modelli for, or ricordi after, the paintings they relate to, which Roy dates to c. 1675/80 (Esther, P.98) and c. 1687 (Eumolpos, P.184). In the case of the Esther drawing, the significant differences between it and the painting indicate that the drawing was a modello underlying the painting (another argument in favor of an attribution to Lairesse himself), rather than a ricordo documenting the composition. Van den Berge dedicated the Esther print to Baron Manuel de Belmonte, the king of Spain’s resident in the Netherlands and probably the painting’s owner. That suggests a date between 1693 (when Belmonte received the title Baron) and 1705 (the year Belmonte died). As Lairesse was thus still alive when the print was done, Van den Berge probably obtained the drawings—or the right to make prints after them—from Lairesse himself. Lairesse probably kept them all those years. In any case, Van den Berge’s Esther print was not executed after the large painting, but after the similarly sized drawing, whose composition it follows closely.

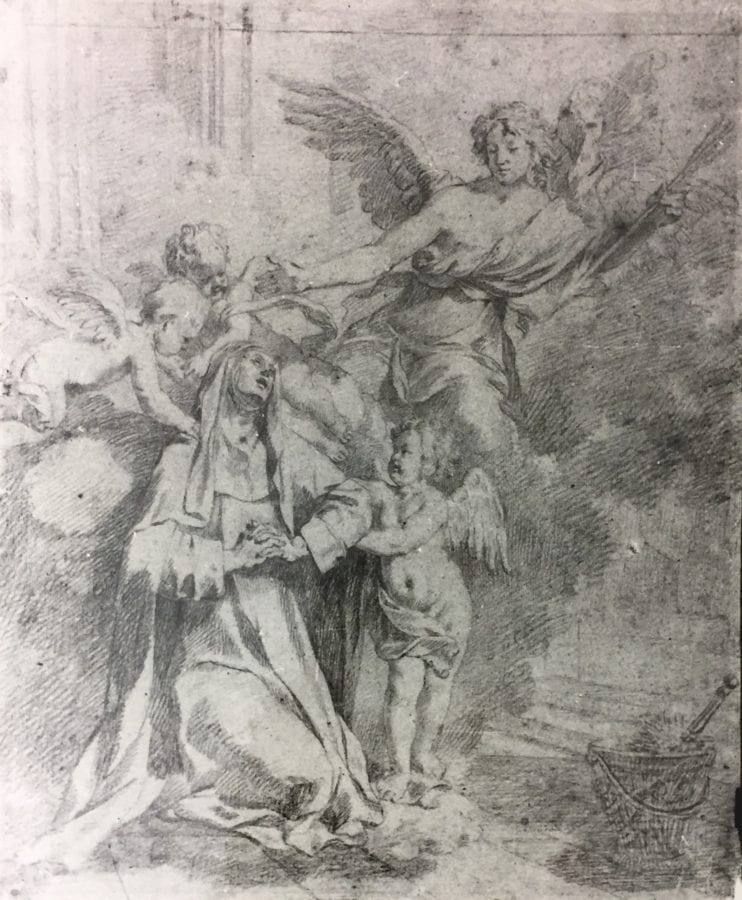

Relatively complex considerations such as these also underlie other cases of red chalk drawings that can be connected to both paintings and prints. What to make, for instance, of a confidently executed red chalk drawing of the Ecstasy of St. Theresa in Cape Town, measuring 32 x 27 cm (fig. 19)? Roy considers it a “copie en sens inverse” after Lairesse’s engraving of the same subject (G.87). However, the drawing is not simply the reverse of the print; it slightly deviates from it compositionally: the angel is larger and its wings are lifted upward, whereas they are turned downward in the print, seemingly indicating an autograph study rather than a slavish copy. Further, the print is inscribed “G. Lairesse pinxit.” A painting showing this composition indeed exists in the church of Saint-Amant-de-Boixe, near Angoulème; it was published by Roy in his supplementary article on Lairesse’s paintings from 2004.37 The print matches this painting in every detail and in its orientation. Where does the drawing fit in? Given the match between painting and print, it is unlikely that the deviating drawing was used to transfer the composition. Yet if it preceded the painting, why then was the painting reversed? Or is the painting, which seems in fact rather weak, a copy after the print, whereas the original painting is unknown to us?

In other cases, red chalk drawings can only be connected with a painting and not a print. This is the case with an Albertina drawing depicting the Wedding of Alexander and Roxane (Pok.6), which largely corresponds to a painting in Bamberg (P.189). In the absence of a print, this seems to be either a preparatory drawing or a ricordo (or both; a final preparatory work could well be kept in the studio after the painting had been sold). As observed by Pokorny, the drawing is gridded, which leads him to think that it indeed preceded the painting (although several already cited examples show that certainly not all drawings done in preparation for a painting are gridded). If, however, one follows this hypothesis, then a group of other red chalk drawings showing known compositions should also be (re)considered, naturally with the (admittedly deficient) norm of quality as a final measure. What to think of a large drawing in the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett (fig. 20), depicting the ransom of a captive? Its composition is that of Lairesse’s painting in the Galleria Colonna, Rome (P.91, 175 x 134 cm.), probably the Slave in Prison (“Een gevangen slaaf van Gerard Lairesse”) mentioned in the death inventory of the wealthy Amsterdam merchant Adolf Visscher in 1702, estimated at no less than two hundred guilders.38 Roy lists the Berlin drawing under “oeuvre en rapport” as an old copy “un peu mechanique.” The drawing, though, deviates from the painting in at least one respect—the added round window—and to my mind shows exceptional drawing skills, notably in the expressive faces of the two standing men. As such, it deserves to be reconsidered as an autograph work. Another red chalk drawing, in the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, relates to Lairesse’s Hagar in the Desert in the Hermitage (P.121) and is—according to Roy, who lists it as an “oeuvre en rapport”—a “copie fidèle” (fig. 21). Even if the drawing might seem slightly dull (certainly no more so than the painting), it differs in some details from the St. Petersburg canvas, and it does not appear to differ significantly in quality from the Albertina drawings. Moreover, it seems that Roy’s assessment was above all prompted by an a priori dismissal of any finished red chalk drawing, rather than an individually weighed choice.

A red chalk drawing of the Last Supper in Uppsala was not known to Roy, as it was first published in 2018 in a catalogue on Dutch drawings in Swedish collections.39 Listed as a “copy after Lairesse (?),” this drawing corresponds to Lairesse’s painted Last Supper in the Rijksmuseum (P.10). However, it differs in details such as the servant boy’s headband, which is absent in the painting. This headband, along with several other details such as hanging curtain ropes, does appear in a more elaborate painted autograph version in the Louvre (P.9). However, motifs in the Louvre painting are either lacking in the drawing (among others, the candleholder, the dog, and the chandelier) or altered (the Caucasian servant boy is African in the painting). Featuring elements from both paintings, the drawing is thus not a mere copy, though its execution lacks virtuosity. If not by Lairesse himself, then it seems at least created within the workshop—for practice, or possibly to be sold.

Did Lairesse also produce some elaborate red chalk drawings solely for the purpose of printmaking? A spectacular drawing that appeared in a Paris auction in 2007, depicting Hercules between Vice and Virtue, might suggest so (fig. 22). No painting of this composition is known to us, but the drawing seems to have served as the example for an engraving by the Amsterdam printmaker Abraham Blooteling (1640–1690) (fig. 23).40 Since Blooteling died the year that Lairesse turned blind, we might presume a collaboration. Was the plan for a painting that was abandoned, or is that painting simply no longer known? In any case, Blooteling’s stiff product deviates in many ways from the brilliantly executed drawing. One of the most remarkable differences is the hero’s sudden mood swing: whereas the print depicts Hercules willingly following Virtue into the temple, the drawing shows him rather hesitant to leave the bacchanal behind, looking over his shoulder as satyrs grasp his cloak, urging him to follow them.

One should remain cautious in attributing Lairesse-related drawings to Lairesse himself, however. That becomes clear from a last example. Among the lost drawings, Roy lists two pendant allegories of an unclear subject, known through engravings by Pieter van den Berge that mention Lairesse as inventor (D.16, 17). Two red chalk drawings, oriented to the reverse of the prints, are in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (fig. 24) and in Braunschweig (fig. 25). But are these the designs on which Van den Berge based his prints? In the case of the Paris drawing, certainly not, for it is fully signed by Julius Henricus Quinkhard (1734–1795), an eighteenth-century Amsterdam artist and copyist. Quinkhard clearly did not copy the print, which differs in too many details, but probably worked after a now-lost original design. Had he not signed his drawing, we might have speculated that it was good enough to be by Lairesse. Moreover, this example makes one realize that the argument that a drawing differing from the print in detail underlines a sense of originality falls short in the case of a copy after an original drawing. As for the Braunschweig drawing, it seems dull and technically limited, but it is surely not by Quinkhard. Is it also a copy after a lost original by Lairesse? Or did Van den Berge simply gather together bits and pieces (as he did with the New Testament series) to cash in on the name Lairesse, even if the drawings he used were inferior studio material?

Versions

The recurring issue of versions (see also figs. 9, 11) is addressed by Pokorny in his discussion of a study for a frontispiece. Two renditions are in Vienna (one by Lairesse, the other possibly by Philip Tideman), and a third is in Munich (Pok.11, 12).41 In 2008, a second version surfaced of another Vienna drawing, the beautiful Diana after the Hunt (Pok.3, here fig. 26), outlined in thin red chalk and worked up with a dark gray brush and a lighter gray wash. After some deliberation, Pokorny considers the Vienna Diana to be the model for a painting in Schwerin and another painted version in Poznan, both listed as autograph works by Roy (P.28, 29). However, the newly surfaced second version—equally high in quality, identical in composition and size, and executed in the same technique—raises questions (fig. 27). Are both drawings autograph works, and if so, why did Lairesse prepare a second version? Could there be a relationship between the two drawings and the two paintings? Were they offered as independent works of art, and/or did Lairesse’s assistants and family members copy them, possibly for commercial purposes? We should not forget that Lairesse’s enterprise experienced rough weather after he was struck with blindness, and any money coming in was more than welcome.

In other cases, the existence of two versions tempts us to accept the better of the two. This is, for instance, the case with two red chalk drawings of a River God with Putti, one in the Louvre and the other in the Teylers Museum, Haarlem (fig. 28, 29). Roy rejects the latter (D.R.10), and suggests it might be a copy after a theater design by Lairesse’s younger brother Jan de Lairesse. He considers the Louvre version (under D.R.10), which is gridded and shows a fourth putto to the left, a contre-épreuve of the Haarlem sheet. Not only do both drawings face the same direction (arguing against the idea of a counterproof); the Paris drawing’s subtle execution—not unlike Father Time in the same collection—marks its superiority over the Haarlem sheet and thus justifies a tentative attribution to Lairesse himself. Likewise, a large, sketchy pen drawing in Berlin (fig. 30) is listed by Roy as a copy after Lairesse’s painting Feast of Venus (P.30, “oeuvre en rapport”). Yet the many differences—several figures in the drawing are absent in the painting—indicate that it is not a mere copy.

Surprisingly, another gridded version of the drawing is in the collection of the Rijksmuseum (fig. 31). Of identical size and composition, but executed in an even sketchier manner, the Amsterdam sheet poses a dilemma: did one of these versions precede the painting? Are both of them copies after a third, now lost, autograph drawing? Or (but this seems unlikely) did Lairesse allow chief assistants to singlehandedly produce designs for paintings? The child in the foreground of the Berlin drawing is done rather clumsily, and the Rijksmuseum drawing, nervous in its execution, also does not necessarily strike one as by Lairesse’s hand (see the unnaturally long, pointed arm of the woman in conversation to the right in both drawings, absent in the painting). Yet if neither drawing is convincingly by Lairesse—and this essentially goes for all these versions—what might have been the purpose: educational or commercial? The same quandary holds for a last example. The Amsterdam Museum possesses a red chalk drawing depicting an Allegory of the Arts (fig. 32), largely similar to a grisaille painting by Lairesse in the Rijksmuseum (P.145), though the composition of the drawing is better balanced, with more space between the two figure groups. Since no print of the composition is known, we are most likely dealing with a preparatory drawing for the grisaille, which presumably had to be condensed compositionally to fit its specific location.42 Roy does not address this difference and lists the drawing as a “copie fidèle” (under P.145). A second, slightly weaker version in Braunschweig is not mentioned.43 Roy’s rejection notwithstanding, the Amsterdam drawing was included in the Enschede exhibition as by Lairesse’s hand, for the reasons explained here, a decision strengthened by the existence of the inferior Braunschweig sheet.

Unrelated Drawings

Two final Albertina drawings also pose questions of how they relate to Lairesse’s known oeuvre. One is a stretched horizontal red chalk drawing of a nude man sitting in front of a sarcophagus, while nymphs and others try to involve him (Pok.7, 30.2 x 56.6 cm.). The musical instruments at his side possibly identify him as Orpheus, mourning the grave of Euridice.44 No print or painting with this composition is known, but Pokorny tentatively connects it with a series of five prints of Bacchic scenes by Lairesse that use the same stretched format (G.109–112). In fact, if we accept that the Vienna drawing was done in preparation for this print series (in which it was not included, for an unknown reason), we might also reconsider a red chalk drawing in the collection of the Göttingen University, which is of a similar size (32.9 x 57.5 cm.) and considered by Roy to be a copy after one of these prints (G.111, “oeuvre en rapport”) (fig. 33). The Göttingen drawing differs from the print in some details—an architectural repoussoir on the left, missing in the print, and a tambourine held by a nymph, added in the print—which makes it not likely to be a copy. The Göttingen collection catalogue, on the other hand, refers to it as a counterproof (“Abklatsch”) of a lost original drawing, but it offers no argument to support that claim.

Like the Orpheus drawing, the only pencil and black chalk drawing in the Albertina, the large Nymphs and River Gods in an Arcadian Landscape, lacks a compositional connection to Lairesse’s known oeuvre. Yet its self-assured execution justifies Pokorny’s attribution (Pok.5, 33.5 x 46.2 cm.). Given the monumentality of the composition, the precise lining, and the grid that covers it, Pokorny suggests that it is a modello for a painting. In several respects, this sheet recalls a drawing in the British Museum (fig. 34). This unpublished drawing, a truly impressive study for the famous Great Bacchanal print (G.106), which Lairesse designed and engraved himself (“Per Gerardum de Lairesse invent: et sculpt”) is also executed in pencil, in a wonderfully detailed manner. Although enhanced with a pen rather than with black chalk, it is comparable to the Albertina drawing in size (37.1 x 43.2 cm.) and in the grid that covers it (once again emphasizing that grids are not necessarily aids for paintings). The London preparatory drawing, which is slightly larger in scale than the print, covers the central part of the print’s composition, capturing the main group of nymphs and satyrs and including many details altered in the final print, such as the hand of the nymph hitting the tambourine, the column drum and the girl hanging over it, the fountain in the background, and the spectacular rays of light falling through the trees. Why, one wonders, would Lairesse have deviated so much from this highly finished and accomplished design? Then again, other promising and elaborate designs, such as the Albertina Nymphs and River Gods in an Arcadian Landscape, did not even make it to the engraving or painting phase at all.

Red and Black Chalk Drawings

The most recent contribution to Lairesse drawings is Annemarie Stefes’s 2002 article in Delineavit et Sculpsit. Stefes discusses two drawings in a private collection that depict Venus and Adonis and Selene and Endymion; both are executed in red and black chalk and carry an attribution to Nicolaes Berchem.45 Although the drawings are signed and dated “Berghem f. 1650,” Berchem specialist Stefes rejects both of them, no doubt correctly, as being too weak. With regard to Venus and Adonis, she points to an original red chalk drawing with the same composition by Berchem in the Rijksmuseum, signed and dated 1648. For the Selene and Endymion, she draws attention to the strikingly similar painting that Lairesse executed for Mary Stuart, now in the Rijksmuseum and datable to around 1680 (P.136). Following this observation, Stefes argues that the young Lairesse copied the drawings after Berchem’s originals shortly after his arrival in Amsterdam, using the Selene and Endymion some fifteen years later as the basis for Mary Stuart’s painting. However, the comparisons that she draws to underline her point—primarily with the not-universally-accepted Self Portrait (D.2)—do not seem decisive. Apart from the fact that both the “Berchem” drawings and the Self Portrait are done in a combination of red and black chalk (the red being used for the flesh, the black for the rest), there are to my mind no technical or stylistic indications that point to the same hand. The “Berchem” drawings seem too gallant and detailed, and at the same time too weak in proportions and shape, to be by Lairesse, even if they were early works. Nonetheless, it is interesting to see that their compositions must indeed have been known in Lairesse’s circle. For not only did the Lairesse workshop appropriate the Selene and Endymion; we come across the Venus and Adonis composition as well: a drawing virtually repeating Berchem’s composition in reverse is held by the Louvre (fig. 35). Van Tatenhove attributed the drawing, long thought to be by Gerard Hoet, to Lairesse’s assistant Philip Tideman, no doubt correctly.

Did Lairesse ever work in a combined red and black chalk technique (except for the alleged early Self Portrait)? Two fine drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art would suggest so much. The first depicts Flora, surrounded by nine putti who crown her with a floral wreath and bring baskets filled with flowers and leaves, joined by a winged male adolescent on a cloud who must be Flora’s husband, the wind god Zephyr (fig. 36). Lairesse wrote about this relatively uncommon subject in his Groot Schilderboek, recommending it for pavilions. Although the scene he described—with an embracing couple—is not the one found in the New York sheet, several elements do overlap, such as the putti with a wreath, the baskets with garlands, Zephyr’s almost naked appearance and wings, and Flora’s dress (“lightly, but with dignity”). The drawing, rather conspicuously signed “G. de Lairesse” on a diagonal quiver, is rejected by Roy and tentatively attributed to Johannes Glauber (D.R.22). It is executed with confident parallel and cross-parallel hatchings, clearly in Lairesse’s vocabulary, in a somewhat angular style. Zephyr’s wings are similar to those found in Lairesse’s print series of the Four Seasons (G.83-86), and, as a whole, the style is reminiscent of the previously discussed preparatory drawing for the Great Bacchanal in the British Museum (fig. 34). Is this a study for a now-lost painting? Several possible candidates are mentioned in inventories and auction records, among them a “Flora met Kindertjes, door G. de Lairesse, extra puyk” in an Amsterdam sale of November 23, 1729.46

The second drawing was purchased by the museum in 2006 and depicts Bacchus pouring wine into a cup held by a nymph as he smiles to the viewer, while another nymph eats grapes and looks up to Bacchus; two putti complete the company (fig. 37). This image, signed with Lairesse’s monogram “GL,” relates to Lairesse’s well-known Bacchus print (G.101), which mentions him as the inventor, painter, engraver, and publisher, but deviates from it in so many aspects that it is best regarded as a variation. For one, Bacchus squeezes grapes in the print, whereas the second nymph who so suggestively eats the grapes is absent; the print only features one putto yet shows a background scene and an entirely different architectural and natural setting. In itself, these differences are not problematic: as has been demonstrated, many Lairesse drawings do not correspond completely to the painting or print they relate to. The effect of the drawing is attractive, with red chalk for the flesh, and black for the rest, over an initial red sketch, but because of its elaborateness it seems a bit too prettified in comparison to his other works. These New York drawings, then, remain enigmatic in terms of their place in Lairesse’s oeuvre.

A last red and black chalk drawing discussed here is listed by Roy as Mars and Venus (D.R.197). Held by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, it depicts the figures of Odysseus and Calypso and thus relates to Lairesse’s spectacular Hermes Ordering Calypso to Release Odysseus in the Cleveland Museum of Art, included in Roy’s supplementary article on Lairesses’s paintings of 2004 (fig. 38, 39).47 The Rennes drawing shows only the two protagonists—in a setting largely overlapping the painting’s composition, except for two columns in the background—while omitting the other figures. It could be one of those rare partial sketches of which the Cupid with Mars and Venus in the Louvre and the Fortitudo and Asia in the Rijksmuseum, both mentioned above, are other examples. Is it coincidental that all three paintings to which these drawings relate can be dated around 1670?Roy, Gérard de Lairesse, P.65 (1671); P.70 (c. 1670/75); P.44bis (1668/70).

Leftovers: Raw Sketches for Paintings

In the paragraphs above, the Delineavit et Sculpsit articles published in the wake of Roy’s book have been my point of departure. Scattered over several other publications—collection catalogues, mainly—are a few other attributions to Lairesse’s drawn oeuvre. In 1994 Charles Dumas and Robert-Jan te Rijdt published a catalogue of the Unicorno collection, in which they discussed the aforementioned David with the Angel.48 In 2006, Jane Turner published a remarkable Allegory of Murder in the collection of New York’s Morgan Library and Museum (since 1959).49 And in 2018, Börje Magnusson recorded six drawings in Swedish public collections, of which some indeed promise to be by the master.50 A Hunter Approaching a Woman with a Child, in particular, done in red chalk with a brown wash and similar in technique to the Venus and Endymion in the Fondation Custodia (D.46) and the Dancing Putti in Leiden (D.162), seems a possible addition to Lairesse’s oeuvre; it was used for an engraving in Lairesse’s Grondlegginge ter Teekenkonst.51

As it was partially my aim to present a bird’s-eye view of the scholarship regarding Lairesse drawings over the years, it was necessary to cite the above-mentioned publications. As a final chord, however, I would like to discuss some drawings from a category that so far has hardly been mentioned: rough or initial sketches for paintings. As remarked previously, Roy lists eight drawings that relate to paintings—all of a sizeable format (c. 25–30 x 37–45 cm), executed in a variety of techniques, and all of them done in ink wash. By contrast, the drawings I want to discuss here seem to precede these more elaborate drawings in the working process. The first is a sketch owned by the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig. The museum holds more than thirty drawings attributed to Lairesse, of which Roy lists two (D.10 and D.R.7). Admittedly, most are not by the master, yet this medium-sized rough sketch should certainly be given to him (fig. 40). The lost painting to which the drawing relates was once in the museum in Dresden (P.205) and is known through a reproductive engraving by the eighteenth-century Austrian engraver Anton Tischler. The print is titled Souvenir de la Mort, a scene inspired by Nicolas Poussin’s Arcadian Shepherds. Lairesse sketched the composition with great efficiency, probably in only a few minutes. Compared to the end result in the form of the print, the drawing shows that from the first moment Lairesse knew how he wanted to compose the scene; he changed only a few positions and figures. The drawing is gridded, no doubt in order to transfer the composition to another support (to the canvas, possibly, or to a more elaborate sketch).

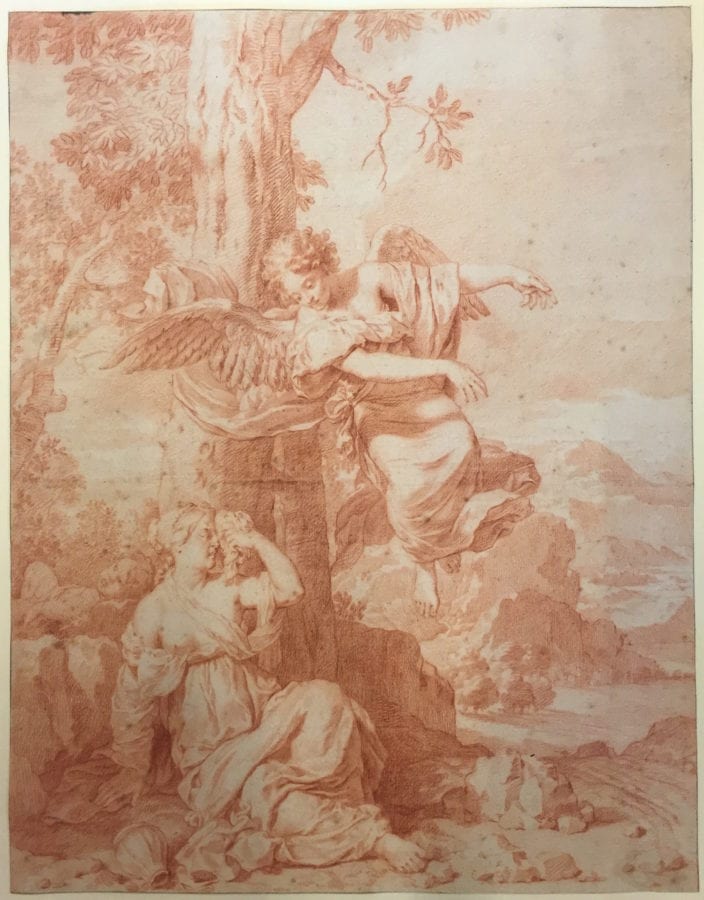

A similarly sized gridded drawing in an American private collection testifies to the same procedure (fig. 41). This sketch, done in a comparable scratchy style, precedes Lairesse’s Abraham Entertaining the Angels, a painting last seen in a Paris auction in 1990 (P.209). The drawing shows some initial figures that are removed from the final painting: a servant to the left, and two men watching on the right. The figure of Sarah approaching from behind with refreshments was added in the painting, which features a pergola and shows a more spacious arrangement overall.

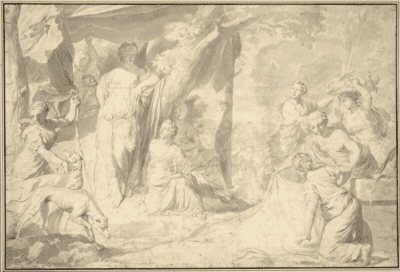

A third drawing of this kind, formerly in the Van Regteren Altena collection, depicts Esther Accusing Haman in the Presence of Ahasuerus (fig. 42). In this case, the composition of the final painting, which we have already discussed above (P.98), was drastically reworked and reversed.52 Esther and her husband, Ahasuerus, changed positions; Haman’s pose was dramatically improved; and the palace setting was enlarged. Since the red chalk drawing of the composition (Albertina, Pok.4) and Van den Berghe’s print after it (under P.98) also survive, this cluster probably forms Lairesse’s most completely documented compositional chain.

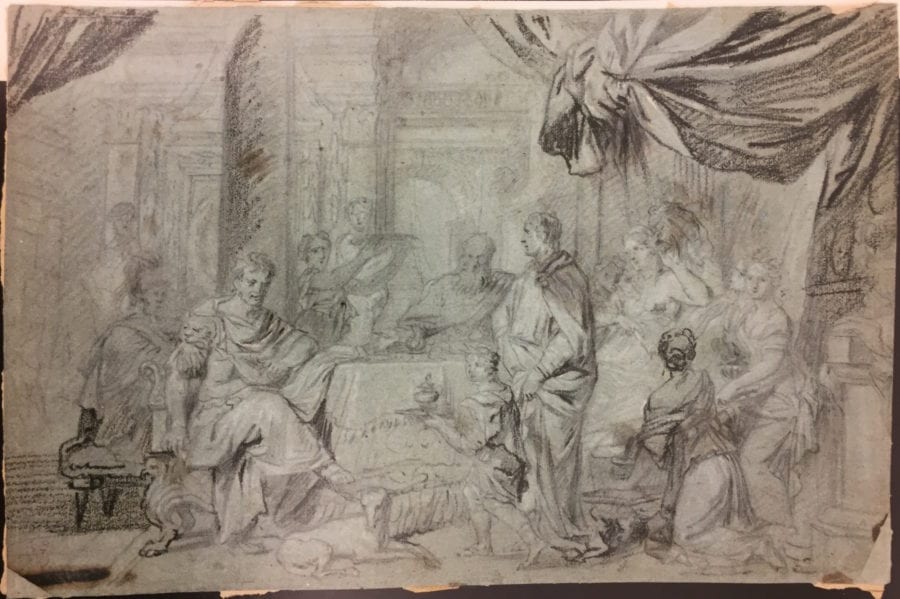

Equally intriguing is a black chalk sketch on blue paper of the well-known Banquet of Cleopatra in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 43). This drawing was auctioned in Paris in 2007 as “after Lairesse” but to my mind could very well be a preparatory sketch for the Amsterdam painting. Its style is rough but sturdy and confident, as one would expect of Lairesse. And although the composition is clearly similar to the Rijksmuseum’s work, it differs in several details, the most important of which is the servant boy in the foreground who brings in the cup with vinegar that will dissolve Cleopatra’s costly pearl. In the drawing, Marc Antony looks at him with surprise, but apparently Lairesse was not satisfied with this conceit and chose to retain only Cleopatra’s female servants, who prepare the drink for their queen.

Interestingly, the composition was partly recycled in a seemingly autograph drawing, auctioned in Paris in 2013 and depicting Alexander the Great Pressing his Ring Against Hephaestion’s Mouth (fig. 44). The drawing is done in a style reminiscent of the two previously discussed versions of Diana after the Hunt. As told by Plutarch, Alexander sometimes received private letters from his mother Olympias. No one was allowed to read Alexander’s letters except for his intimate friend, Hephaestion. Once when Hephaestion opened one of Olympias’s letters, Alexander pressed his ring to Hephaestion’s mouth, thus urging his discretion. The drawing depicts this moment in a composition completely modeled after the middle part of the Banquet of Cleopatra, including the identical dog (in reverse) and the standing figure to the right, here a female representation of Silence, pressing her finger to her lips. Was the drawing an adaptation of the Cleopatra composition, or were both executed around the same time? A very rare subject, it partially relates to a bas-relief by Rombout Verhulst in the Amsterdam Town Hall. The relief, situated above the entrance to the Secretary’s Office, where discretion was required, depicts a female allegory of Silence, likewise pressing her fingers to her lips.53 Lairesse might have taken inspiration from Verhulst’s relief, or possibly the drawing was an initial design for a (never executed?) painting that was somehow connected with the Secretary’s Office or with one of its officials.

We know for sure that Lairesse intended to work for the Town Hall, as is underlined by his painted modello for the Citizen’s Hall’s east lunette (P.173) in the Amsterdam Museum—described in 1686 by the Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin after a visit to Lairesse’s studio as “die Eskisse, die da wahr gemahlt ins kleine vor dem Rathauss”—and the drawn sketch that likely preceded it, last seen in a 1925 Paris sale (D.158). Another sketch (recently circulating in the Dutch art market as a Lairesse) is circular in shape and depicts the Amsterdam Maiden with putti, a map of the city, and the Town Hall’s west pediment in the background (fig. 45). This work shows considerable overlap with the central group in the Paris drawing. Its style and technique are somewhat nervous. One wonders if Lairesse himself was responsible for this quick sketch, or if it is more correctly attributed to someone from his circle. That could possibly be his son Jan, to whom Roy attributes another circular drawing in the Rijksmuseum depicting Time and Truth (D.R.2), which shows an affinity in its execution. If the sketch precedes the Paris drawing—as a first conceptualization—an attribution to anyone but Lairesse himself would seem improbable. However, if the sketch was really a first step in thinking about the lunette, its circular shape remains enigmatic, to say the least. We must therefore consider the possibility that it might have been a private design by someone from Lairesse’s close circle; that is, for someone involved with the construction of the Town Hall, possibly a burgomaster.54

At any rate, Lairesse seems to have been preoccupied with the lunette and its design. Already in 1661—four years before Lairesse’s arrival in Amsterdam—a book was published with prints of the decorations of the Town Hall, based on drawings by Jacob Vennekool after designs by the building’s architect, Jacob van Campen. One of the prints depicts the east wall of the Citizen’s Hall and shows Van Campen’s intended design for the east lunette. This was an allegorical depiction of Aurora, with Apollo on his sun chariot pulled by horses and led by the ascending Aurora herself, while a personification of the Night flies away in the clouds, all set underneath the semi-circular zodiac (fig. 46). Lairesse must have been keenly aware of Van Campen’s composition, for he hardly tried to conceal the fact that he appropriated it for his spectacular Aurora ceiling-piece of c. 1675, now in the Rijksmuseum (P.84). A drawing in Munich, listed by Roy as probably by Philip Tideman (D.R.80) and done in a style comparable to the circular drawing, shows an unmistakably similar composition (fig. 47).Wolfgang Wegner, in Die niederländischen Handzeichnungen des 15.–18. Jahrhunderts (Kataloge der Staatlichen Graphischen Sammlung München 1), 2 vols. (Berlin: Mann, 1973), 99, cat. 682, puzzlingly proposes a comparison with the De Graeff ceilings.55 Did Tideman later rework his master’s composition for a project of his own, or might the Munich drawing have been Lairesse’s own preliminary sketch for the Rijksmuseum ceiling? We should not immediately reject the latter option, for the drawing shows certain stylistic affinities with another, hitherto unnoticed drawing in Braunschweig, again done in a similar sketchy style, which also echoes Van Campen’s lunette design. Here we see Apollo riding his horse-driven chariot, accompanied by the triumphant Aurora, set underneath the arc of the zodiac (fig. 48). To a large extent, this drawing matches the composition of Lairesse’s magnificent Apollo and Aurora painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is signed and dated 1671 (P.67) and includes the zodiac elliptical, although different signs are included (Taurus, Gemini, and Cancer in the drawing; Virgo, Libra, and Scorpio in the painting). As such, the Braunschweig sheet contains plenty of features that argue in favor of it being an autograph sketch, produced c. 1670/71. As demonstrated by Walter Liedtke, the New York painting is a portrait historié, executed for Nicolaes Pancras (16221678), a five-time burgomaster between 1667 and 1675 (Pancras also commissioned Lairesse’s c. 1670 Paul Emile painting series; P.55–62). His son Gerbrand and daughter Maria assume the roles of Apollo and Aurora.56 Nicolaes Pancras’s father, the burgomaster Gerbrand Pancras, had been among the promoters of the new Town Hall (his grandson Gerbrand Pancras van Erpecum was among the children to lay down the first stones in 1648), and the Pancras escutcheon is found in the Town Hall’s Insolvency Chamber.

By so openly referring to Van Campen’s intended lunette composition for his commissioner, Nicolaes Pancras, Lairesse might have tried to land the commission to paint the still-empty east lunette and secure himself that coveted spot amidst the great painters of his time. Yet Pancras died in 1678, and in 1679 Adriaen Backer was commissioned to paint the west lunette, with an option to paint the east lunette as well.Paul Vlaardingerbroek, Het paleis van de Republiek: geschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam (Zwolle: Wbooks, 2011), 150.57 Given the existence of Lairesse’s drawn sketches and the Amsterdam Museum’s painted modello, the idea of painting the east lunette must have consumed him further. Yet problems with the rooftop construction during the 1680s did not help, and in 1689/90 Lairesse went blind. In 1703, when the problems concerning the roofs were finally resolved, Lairesse’s pupils Jan Hoogsaat and Gerrit Rademaker finally received the commission for both the ceiling and the east lunette, after designs by another Lairesse protegee, Jan Goeree, and his probable student Simon Schijnvoet.58

Final Remarks

And so Lairesse’s lightning career ended in a twenty-one-year stretch of darkness, prefiguring the course of his reputation. After initial acclaim, his prestige suffered gravely during the later nineteenth century, reaching an absolute low in the first half of the twentieth century.59 In recent decades, a rehabilitation has taken place. Yet research into Lairesse’s achievements has followed unequal paths, often more concentrated on his art-theoretical writings than on his art, and with more attention to his paintings than his graphic oeuvre. In the wake of the Eindelijkl! De Lairesse exhibition in Enschede, this article has tried to shed new light on the state of scholarship regarding Lairesse’s drawings. By discussing chronologically the publications dedicated to the subject, I have tried to delineate its incomplete character.

At the same time, I have called attention to some forty drawings that can be attributed to Lairesse, many of which have received little previous attention. These drawings show a staggering variety of style, execution, presumed function, and ambition, and yet they all have a direct link with Lairesse’s universe. As such, they trigger questions about authorship and function, especially in relation to his studio practice. Most important, however, they add significantly to the accepted body of drawings. Because it was necessary to consider a substantial amount of revised and new material, other aspects that would surely contribute to a better understanding of Lairesse’s drawings and their function have mostly been left out here. These include an analysis of Lairesse’s own writings on the art, techniques, and functions of drawing, and more advanced technical research, including analyses of the materials used, signatures, traces of indentation, and paper and watermarks.

To accomplish this, many of the drawings will have to be studied first hand. Although the ever-increasing possibilities of online access to collections, auctions, and the art trade is of great help, this does not constitute a sufficient level of overview. To give a sobering example: of Roy’s D.R. category of rejected drawings, consisting of 211 drawings, only fourteen are (understandably) illustrated, which means that 197 are not. Although I gathered from various sources the images of 112 of these often-obscure drawings, eighty-five have so far remained beyond my scope. In fact, of the 126 drawings rejected by Roy for which I had images at my disposal, only six are discussed here, because they connect well to drawings discussed by previous authors. Others, however, have so far been omitted, although they deserve to be discussed. The same essentially applies to several drawings of interest encountered in museum and private collections as well as the art trade. By adding the group of drawings discussed above to the more established part of the oeuvre, it has been possible to expose the current lacunae. Undoubtedly, not all the attributions and suggestions proposed here will stand the test of time, but hopefully their publication will spur renewed discussion. Ultimately, an artist as important as Lairesse deserves a nuanced catalogue raisonné of his drawings.