This article argues that Hendrick ter Brugghen included specific physical, environmental, and cultural allusions to contemporary attitudes about the plague’s origins, symptoms, and remedies in his painting Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene. These references established a recognizable setting for the integration of approaches to healing from the past with those of the artist’s own time. With this framework, ter Brugghen was also able to address the divergent religious beliefs of his multiconfessional community during a period of recurring epidemic outbreaks. The artist presented the plague-ravaged present as the setting for his depiction of the Christ-like figure of the martyred saint, whose body reveals signs of the dreaded disease. To this well-established Roman Catholic miracle-working intercessor and source of spiritual comfort, ter Brugghen added the post-Tridentine figure of the caregiver Irene, who provides comfort in a temporal charitable act. Her close physical contact with Saint Sebastian underscores her willingness to remain and heal, which corresponds closely to the position of contemporary Dutch religious and secular caregivers, especially orthodox Calvinists, who refused to flee during the recurring plague seasons.

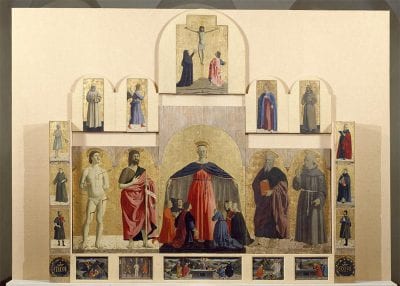

Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene, signed and dated 1625, portrays a haunting image of a failed execution from the early Christian past along with references to contemporary plague outbreaks (fig. 1). Having survived an initial attempt on his life by Roman archers, Saint Sebastian became closely associated with arrows, which reflected his worldly career as a professional soldier, his religious role as a militant defender of the new faith, and eventually his intercessory action as a martyr capable of healing the plague. Saint Sebastian, pierced with projecting shafts, was often represented with the Virgin Mary or as a solitary figure resembling Christ in thaumaturgic pictures that served as spiritual cures for the afflicted. In the late sixteenth century, the figure of Irene was restored to the religious narrative in order to encourage the community of the healthy to practice Christ-like charity toward the sick as an act of temporal care. Both the contemplative comfort offered by Saint Sebastian and the active intervention of Irene were urgently needed in the early seventeenth century, when the plague swept through Rome and Utrecht, where ter Brugghen (1588–1629) lived and worked.

In his striking painting, ter Brugghen conflated Roman Catholic and orthodox Calvinist beliefs in a scene that resonates with the past and present. Ter Brugghen acknowledged established Roman Catholic pictorial and iconographic traditions by representing Saint Sebastian as a miraculous healer of the plague. In addition, he incorporated post-Tridentine modifications by including the figure of Irene, whose role as a secular healer shifted the religious narrative from the saint’s death sentence to his unexpected recovery. The inventive depiction of the seated saint and his female rescuer at the scene of the foiled execution was enhanced by specific physical, environmental, and cultural allusions to prevailing seventeenth-century attitudes about the plague’s origins, symptoms, and remedies. These previously unrecognized references situate the saint’s suffering in the contemporary context of recurrent plague eruptions in Utrecht. This expanded analysis of ter Brugghen’s depiction of Saint Sebastian and Irene also affirms the orthodox Calvinist position to remain in the community of sufferers and to avoid fleeing the epidemic. Identifying the intersection of tradition and innovation in this painting reveals ter Brugghen’s sensitivity to the multiconfessional nature of his community, where diverse beliefs were practiced and proselytized.

The theme of Saint Sebastian originated in Italy, where a number of Utrecht painters traveled to study the celebrated artworks of classical antiquity, the Renaissance, and Caravaggio and his followers. As the first artist from this group to head south, ter Brugghen arrived in Rome in late 1607 or early 1608 and remained in the city until sometime in 1614, when he returned to Utrecht.1 He might have visited Rome a second time around 1620.2 Nevertheless, the artist left no documented artwork in Italy.

His contemporary, Dirck van Baburen (1595–1624), on the other hand, received both public and private commissions while in Italy. He lived there from about 1612 until the fall of 1620 or the winter of 1621, when he returned to Utrecht.3 The approximately nine paintings completed by van Baburen during his Italian period are far outnumbered by Gerrit van Honthorst’s Roman works. Leaving for Italy around 1613, van Honthorst (1592–1656) famously achieved the nickname “Gerardo delle Notti” by the time he returned to Utrecht in 1620.4 Ten years after ter Brugghen’s departure, Jan van Bijlert (1598–1671) left for Italy around 1617 and returned to Utrecht in 1624.5

These artists all depicted scenes of Saint Sebastian after returning from Italy. The impetus was likely their encounter with fellow citizens dying from the plague in Utrecht. Especially high mortality rates resulting from the disease were recorded during the period between 1613 and 1617, when ter Brugghen came home and van Bijlert left, and during the years 1624 and 1625, when ter Brugghen and his contemporaries produced the greatest number of images featuring the plague saint.6

The earliest work corresponding to these Utrecht outbreaks includes both Saint Sebastian and Irene and was painted sometime in the 1610s by the relatively unknown Cornelis de Beer (active 1616–1630), who entered the Utrecht painter’s guild in 1616, the same year as ter Brugghen (fig. 2).7 Subsequently, Honthorst painted a solitary figure of Saint Sebastian in a work of ca. 1620 and van Baburen and his workshop completed horizontal compositional versions depicting Saint Sebastian and Irene during the particularly lethal plague seasons in Utrecht between 1623 and 1625 (fig. 3 and fig. 4).8 During this same period, van Bijlert painted a scene closely following van Baburen’s horizontal prototype (fig. 5) and ter Brugghen painted the Oberlin canvas.9

Similarities in these depictions support the strong possibility that the artists were aware of each other’s paintings and may have looked to the same pictorial source. It has been suggested that van Baburen and ter Brugghen shared a studio during the period when their versions were completed, and van Honthorst’s depiction of the saint with an extended straight arm recurs in the paintings by van Baburen, van Bijlert, and ter Brugghen.10 In these instances, the seated or supported figure of the saint is presumably dead or dying and remains bound to the tree where his martyrdom was to occur. In contrast to the many depictions showing Saint Sebastian standing upright, the preferred choice of Italian artists, the paintings by the Utrecht artists present unusual compositional alternatives evident in only a small number of extant Italian predecessors. For example, the position of the saint’s body in one Italian painting is strikingly analogous to the Dutch depictions (fig. 6).11 This work has recently been attributed to Angelo Caroselli (1585–1652), whose religious and genre paintings strongly influenced the art of van Baburen and the other Utrecht painters living in Rome.12 Since the hagiographic texts and the representations and connotations of the saint, especially regarding his association with the plague, were conceived and refined in Italy, Caroselli’s influence as a pictorial and iconographic source for the Utrecht contemporaries is persuasive. Ter Brugghen’s painting, in particular, closely corresponds to Caroselli’s version and shows a profound understanding of the Italian origins of Saint Sebastian’s life and enduring significance.

Italian Sources for Sebastian as a Plague Saint

The earliest written account of the saint’s life comes from a fifth-century source, the Passio Sancti Sebastiani. According to this biography, Sebastian was a favored captain in the Praetorian Guard of Emperor Diocletian around the year 300. His public support of Christians resulted in many conversions, and he continued to proselytize even when the emperor asked him to stop. As a result, Sebastian was ordered to be shot with arrows. So many of them passed into his body that the Passio records the victim looked “like a hedgehog.”13 Sebastian miraculously survived and was cured by Irene in her home. In response to his ongoing proselytizing for Christianity, Sebastian was arrested a second time and beaten to death with clubs. His body was thrown into the city’s sewer but was subsequently recovered and eventually buried in the catacombs along the Via Appia.14

The Passio does not connect Saint Sebastian with the plague. However, it does locate his burial next to Saints Peter and Paul, which led to his recognition, by the seventh century, as the third patron saint of the city of Rome. At about the same time, Saint Sebastian was first credited with ending plague epidemics in both Rome and Pavia.15 As Sheila Barker has persuasively argued, these early miracles were not the result of any specific antipestilential powers wielded by Saint Sebastian. Rather, they developed from the saint’s close association with Saints Peter and Paul and with the miraculous power of his relics, especially his arm, which were brought from Rome to Pavia in 680. In fact, Barker argued that the emergence of a “direct cultic link” between Saint Sebastian and the plague only occurred with the publication of Jacobus da Voragine’s Golden Legend from about 1260.16 Subsequently, Saint Sebastian was regarded as a particularly efficacious intercessor against the plague.17

Early depictions of Saint Sebastian resemble representations of Saints Peter and Paul, the other patron saints of Rome. For example, in a late seventh-century mosaic in San Pietro in Vincoli, Saint Sebastian appears as an old man with a white beard who is dressed in a ceremonial white tunic and holds a martyr’s crown (fig. 7). By the tenth century Saint Sebastian’s attempted execution appears in a narrative fresco cycle in the church of San Sebastiano on the Palatine Hill where the act allegedly occurred.18 At this point in the iconographic development, Saint Sebastian had no clear pictorial association with the plague. His depiction as a victim of Diocletian’s archers simply underscored his role as a fellow soldier who defiantly defended the emerging early Christian church.

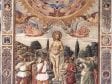

Not surprisingly, images directly linking Saint Sebastian to the plague emerged after the Golden Legend disseminated the story of his healing powers and the disease devastated the city-states of Italy during the middle of the fourteenth century. In his altarpiece for the Duomo in Florence (1375–80), Giovanni del Biondo presented for the first time the visual association between the saint’s martyrdom and his healing power19 (fig. 8). In a scene that closely resembles Christ’s crucifixion, Giovanni’s central panel shows the saint elevated above his executioners, while in the lower section of the flanking left wing, Saint Sebastian and the Virgin Mary intervene to end the plague in Pavia. Together, the iconic presentation of the arrow-riddled body of the saint and the narrative scene of the Pavian intercession translated the written account of the Golden Legend into a riveting visual presentation.

As Saint Sebastian’s healing actions during the plague at Pavia became better known through text and image, the excessive number of arrows that punctured the saint’s body was soon connected to the piercing shafts that delivered the plague and destruction in pagan literature and Old Testament scripture. The tale of how Apollo inflicted plague on the Greeks during the Trojan War as told in Homer’s Illiad was well known: “First he went for the mules and circling dogs but then, launching a piercing shaft at the men themselves, he cut them down in droves—and the corpse-fires burned on, night and day, no end in sight.”20 Familiar, too, was the Old Testament account of God as an agent of pestilence and plague in Deuteronomy 32:41–42, “I will render vengeance to mine enemies, and repay them that hate me. I will make my arrows drunk with blood.”21

The arrows of Saint Sebastian’s execution also led to his role in depictions of the Madonna della Misericordia. In his painting completed in 1372 during an outbreak of the plague in Genoa, Barnaba da Modena transformed the traditional image of the merciful Virgin Mary interceding for her petitioners into a powerful guardian who shields her worshipers from angels wielding plague-tipped arrows (fig. 9).22 By the middle of the fifteenth century, Saint Sebastian materializes under the mantle of the Madonna della Misericordia in three banners (gonfaloni) by Benedetto Bonfigli. Carried during penitential processions following recurrences of the plague, these banners show the body of Saint Sebastian pierced by a multitude of arrows which fail to threaten the citizens gathered around the Virgin Mary because he has absorbed their blows. In the gonfaloni, the mediating and protective role of the Virgin Mary is fortified by Saint Sebastian, who kneels at the outer edges of the Madonna’s cloak and articulates the pleas of the people. This is made clear by the banderole that emerges from his mouth in the example from Corciano, “O Mary, flower of virgins, like a rose or a lily, pour out prayers to the Son for the salvation of the faithful” (fig. 10).

Saint Sebastian assumes the main intercessory role in a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli in San Agostino in San Gimignano, which was completed only weeks after signs of the plague returned to the city in June 1464 (fig. 11). In this entirely novel iconographic solution, Saint Sebastian takes the place of the Madonna della Misericordia, who joins her son, Christ, in heaven.23 As in earlier depictions of the Virgin of Mercy, Saint Sebastian assumes both a mediating role, as the inscription on the plinth, “Sancte Sebastiane Intercede/pro devote populo tuo (Saint Sebastian intercede for your devoted people),” makes clear, and a defensive function, as the twisted arrows vanquished by his blue cloak reveal. Together, Saint Sebastian with the earth-bound supplicants below and Christ and the Virgin Mary above, appeal to God the Father, who holds a plague arrow. The people of San Gimignano gather beneath the mantle now borne by Saint Sebastian, who no longer absorbs the arrows of his attempted martyrdom and the plague but repels them. The epidemic was said to have ceased through Saint Sebastian’s intercession on July 28, 1464, the very day of the painting’s dedication, when reportedly thirty-eight people were delivered from the disease.24

Now Saint Sebastian not only assumes the intercessory role of the Virgin Mary but with his long hair and beard, halo, and crown, he also resembles Christ. This is evident in a second work by Benozzo commissioned by the Collegiata “for the health of the people of San Gimignano and to procure their deliverance from death” (fig. 12). In this painting, the bound, Christ-like nude figure of Saint Sebastian is juxtaposed with Christ’s bleeding hand, shown above his head, and with the depiction of the Crucifixion below his feet. The full visual presentation underscores the saint as an imitator of Christ who suffers for humanity by bearing the divine wrath of the plague. Both paintings by Benozzo in San Gimignano worked in concert to advance the cult of Saint Sebastian.25

As waves of plague, typhus, and dysentery overwhelmed the cities of Italy in the later fifteenth century, the image of Saint Sebastian as a lone intercessor proliferated. In many of these, Saint Sebastian shed his overt associations with the Madonna della Misericordia and his pictorial and iconographic connections to Christ were strengthened. For example, in Piero della Francesca’s Madonna della Misericordia, painted for a confraternity of mercy in Borgo Santo Sepolcro, the formidable saint stands alone, nearly nude, his body pierced by a small number of arrows—an allusion both to his martyrdom and to his efficacy in deflecting the scourge of the plague (fig. 13).26 Subsequently, Saint Sebastian either appears in narrative scenes of the attempted execution that resemble Christ’s crucifixion or in devotional works that focus on the idealized exposed body of Saint Sebastian bound to an upright tree or column in imagery that is strikingly analogous to scenes of the Flagellation of Christ. The painting by Antonio and Piero Pollaiuolo completed in 1475 for the Servite church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence presents a richly detailed account of the attempted execution, while artworks by Antonello da Messina (1475–76), Sandro Botticelli (1474), and Perugino (ca. 1495) offer the alternative depiction of the isolated, suffering saint (fig. 14, fig. 15, fig. 16, and fig. 17).

As Louise Marshall has demonstrated, the lone figure of Saint Sebastian as a Christ-like redeemer eventually outnumbered narrative scenes. Representations that highlight the injured body of Saint Sebastian provided worshippers with a direct connection to his suffering and recovery and to his related intercessory role in relationship to the plague.27 Like Christ, Saint Sebastian experienced martyrdom, but did not die. He attracted the burst of plague arrows sent by God and grounded them harmlessly in his own flesh. To those praying for his intercession, Saint Sebastian’s wounds corresponded to plague buboes and his miraculous recuperation mirrored Christ’s resurrection that brought redemption and healing to humanity.28

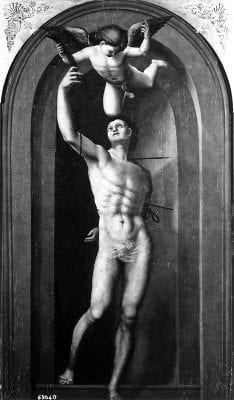

The body of Saint Sebastian also served as a suitable subject for Italian artists wishing to demonstrate their skills in rendering an athletic male nude with the physical potency to withstand arrows.29 Sometimes, the accentuation of these features detracted from the saint’s holiness. According to Giorgio Vasari, Fra Bartolomeo’s painting from 1514–15 of the naked saint caused women to sin at the sight of it.30 The friar’s shockingly realistic painting was quickly removed from the church of San Marco in Florence and is now known only by a copy in Fiesole31 (fig. 18).

This type of representation troubled the Roman Catholic reformers at the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563. Contemporaneous with these discussions, the polemicist Giovan Andrea Gilio (d. 1584) pointed to the errors found in religious imagery and provided advice on how to produce decorous, didactic, and inspirational works of art.32 In his treatise from 1564, Gilio admonished artists who used the saints, including Saint Sebastian, as an excuse to depict perfected figures without emphasizing the reality of their martyrdoms.33

Twenty years later, Gian Paolo Lomazzo (1538–1592) referred to Vasari’s commentary on Fra Bartolomeo’s lascivious Saint Sebastian in his guide to decorum in picture making. Although he had not seen the friar’s painting, its reputation led him to recommend that artists should not paint the saint’s body as sensually nude but, instead, as a martyr hanging from a tree with his flesh marked by bleeding wounds.34

Despite these specific renunciations, painters continued to emphasize the perfected figure of the saint, and even its frank sensuality and eroticism. Lodovico Caracci’s painting from around 1600 and Guido Reni’s seven depictions of the saint from the 1610s make this approach especially clear (fig. 19 and fig. 20).35 Reni’s paintings were likely among the representations that troubled the post-Tridentine reformer and archbishop of Milan, Federico Borromeo, in 1624, when he lamented that so many painters showed off their skill by representing the saint as youthful, healthy, and nude even though historically the saint was “actually an old man.”36

The practice of eroticizing Saint Sebastian reached as far as Utrecht, where Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638) completed his version in 1600 (fig. 21). In his representation, Wtewael focused on the sensual elegance of the smooth, twisting body of the saint in the center of the composition and referred to the impending execution by including a dramatically positioned cherub holding martyr’s palms, two archers binding the saint to the tree trunk, and arrows, a cross bow, and a filled quiver. Only these peripheral features identify the central figure as Saint Sebastian, whose nearly nude body alone makes no direct connection to his role as a martyr or as an intercessory and redemptive healer. In her commentary on this painting, Anne E. Lowenthal noted the explicit sexuality of Wtewael’s representation of Saint Sebastian and contrasted the piece to the “deeply felt religious expressions” found in the interpretations of van Honthorst and ter Brugghen.37

Although ter Brugghen also idealized the body of Saint Sebastian in his painting from 1625, the saint no longer awaits or defeats death but instead barely clings to life. Here ter Brugghen recognized the rich pictorial and iconographic traditions established in Italy that linked the saint to Christ and the plague. At the same time and in contrast to the Italian versions, he introduced compositional and figural features that underscored the uncertainty of Saint Sebastian’s recovery in a contemporary context, even as he highlighted the important role of Irene as the saint’s healer.

The Introduction of Irene, Saint Sebastian’s Rescuer

The addition of Irene was a fresh iconographic development, which emerged during the Counter Reformation with the scholarly writings of Cardinal Caesar Baronius (1538–1607). Having investigated a wide range of historical sources, Baronius modified the account of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom in both Martyrologium Romanum, published in 1586, and his authoritative twelve-volume church history, Annales Ecclesiastici.38 In the Martyrologium, Baronius recommended that Saint Sebastian be depicted as an old bearded man as he appeared in the mosaic in San Pietro in Vincoli.39 In volume three of the Annales (published in 1592) he recounted Irene’s role in the rescue of Saint Sebastian.40 Although she had been mentioned by name in the fifth-century Passio and was referred to as “una casta donna” (a virtuous woman) in a seventh-century Milanese hymn, Irene did not appear in the popular Golden Legend, which simultaneously erased her role in Saint Sebastian’s biography and kindled his associations with healing and the plague.41 In Baronius’s amended description, Irene returns to the narrative as a female figure who comes at night to bury the executed victim but instead discovers he still lives. She rescues him and nurses him back to health in her home. The influence of Baronius’s account is evident in the artworks that turn away from the solitary, sensualized figure of Saint Sebastian and instead underscore Irene’s role as a healer.

Baronius’s scholarship, especially the Annales, was enthusiastically embraced by a wide range of religious and secular leaders who advocated for vernacular versions that would reach an even greater number of readers.42 In the Netherlands, his work was quickly assimilated and translated by Roman Catholic scholars, who were moved by his well-argued claims supporting the history and legitimacy of the Roman Catholic faith.43

By the time ter Brugghen and his contemporaries turned to the story of Saint Sebastian, Baronius’s account was widely known in translation. In his rendition from 1619 of the saint’s biography, the Jesuit Heribert Rosweyde (1569–1629) described Irene’s intention to bury Sebastian’s body, but when she finds him alive she cures him.

The next night, the widow of Castulus, Irene of Rome, went secretly to the place where Saint Sebastian had been shot in order to retrieve his body to bury it, and found he was still alive. She brought him to her house and nursed him back to health. Christians heard of his recovery and came to admonish him and beg him with tears in their eyes that he should leave in order to avoid falling, again, into the hands of such a cruel tyrant.44

Additional passages tied to Saint Sebastian’s feast day of January 20 recount his role as a plague saint.

This is the life and death of the glorious knight and most pious Captain of Christ, Sebastian, whom we may recognize as a double martyr because he was twice tormented and left for dead. All Christians have a great devotion to this saint because of the great power of his intercession, especially in the time of the plague, when he takes pity on all those who ask for his help.45

As these accounts of Saint Sebastian’s final hours became broadly circulated, artists started to represent the figure of Irene as she attends the body of the seemingly dead Saint Sebastian at his execution or, in at least one unusual example, at his bedside.

At about the same time that Cornelis de Beer completed his painting (see fig. 2), the Spanish painter Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644) also depicted Irene in a painting intended for a hospital dedicated to Saint Sebastian, where a charitable confraternity cared for patients (fig. 22).46 Acknowledging the setting for this work, Pacheco showed Irene wearing the white-veiled habit of a convent nun who works in the infirmary, tending to a bearded mature Saint Sebastian, who convalesces on a bed in a domestic setting.47 Depicted as a sister, Pacheco’s Irene grounds the remote story of Saint Sebastian in the present in a scene only rarely rendered and undoubtedly responsive to Baronius’s restoration of Irene’s central role.48

Visible through the back window of Pacheco’s painting, a scene of the saint confronted by his executioners, based on a Flemish print by Jan Harmensz. Muller, presents the events that explain his wounded state. Irene’s ministrations become the fulcrum for a look back to the recent past, recorded through the window, and to the imminent future, known to the viewer as the inevitable conclusion of Saint Sebastian’s sacrifice.49 By emphasizing Irene’s activities as a nurse, Pacheco focused on the moment in Saint Sebastian’s narrative that directly paralleled the work of the contemporary confraternity members who volunteered to assist the impoverished sick.50 Since the arrows that caused the saint’s wounds were metaphors for the arrival of the plague, the healing of Saint Sebastian aligned closely with this specific contagious disease. Against the backdrop of repeated outbreaks, depictions of Irene in Saint Sebastian’s narrative underscored her willingness to risk her own life in the charitable act of burial, which was not necessary, and of healing, which was. Her actions had the effect of stimulating this inclination in others.

Thus the figure of Irene provided an alternative narrative for viewers of images that featured the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. The traditional image of the solitary figure of the wounded saint with its striking pictorial and iconographic parallels to Christ that was so often represented in Italian art directly addressed the bodily needs of the afflicted as a miracle-working spiritual cure for a temporal ailment. The addition of Irene encouraged the community of the healthy to practice Christian charity by providing medical care to the sick, as straightforwardly depicted in Pacheco’s work. In representations that unfold at the execution site, it also encouraged the provision of burial services for the dead, as implied in the paintings of ter Brugghen and his fellow Utrecht Caravaggists.

Ter Brugghen’s Painting and the Plague in Utrecht

Ter Brugghen, van Baburen, and van Bijlert all avoided the fragmented distinction between the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian and Irene’s caregiving found in Pacheco’s representation of the newly acknowledged female protagonist. Instead, these artists expanded the traditional narrative to show Irene at the site of the attempted execution where she intends to retrieve the body of the presumably deceased martyr, but where she instead undertakes her initial acts of healing.

Distinguishing his work from that of his contemporaries, ter Brugghen underscored the precarious conditions of his own time as the backdrop for this scene from Saint Sebastian’s life. Natasha Seaman has called this strategy “meta-historical”: when ter Brugghen represented religious scenes, he incorporated iconographic, stylistic, and compositional archaisms along with characteristics drawn from Caravaggio’s naturalism, materiality, and references to the present day.51 Following the conventional features of a traditional altarpiece in scale and size, the representation and placement of Saint Sebastian’s body in the painting in Oberlin (see fig. 1) evokes comparisons with Christ as the Man of Sorrows and with the Crucifixion. The strikingly convincing three-dimensionality of the figures and the powerful tenebrism of the setting reveal the influence of Caravaggio’s art. Yet the careful placement of the arrows, which clearly demarcates the sign of a cross through the body of the suffering saint, draws attention to the physicality of the two-dimensional picture plane and highlights ter Brugghen’s unique synthesis of illusion with the painted surface of his canvas.

As evidence of ter Brugghen’s fusion of the past and present, Irene is shown carefully extracting one of the arrows. This unifies the sacrificial nature of the Christ-like saint with her practical charitable actions in a setting redolent with the reality of the plague in Utrecht. The ominous setting alludes to the ambient conditions of a plague summer. The body of the saint appears to suffer from the very disease he has been credited with curing, and Irene embodies the efforts of contemporary caregivers to provide burial services and medical treatment to the victims of the epidemic. The figure of Irene, in particular, speaks specifically to ongoing debates about how to respond to the plague. With her self-sacrificing willingness to remain and care for Saint Sebastian, Irene rejects fleeing, which was a common and rational reaction to the dreadful disease.

By the time he depicted the resolute Irene, ter Brugghen had witnessed the waxing and waning of the disease and confronted directly the threat of death by plague while living in Rome and Utrecht. These seasonal outbreaks typically occurred during warm weather, when ideal conditions existed for the flea whose bite transmitted the disease from rats to humans.52 For example, after a horrific summer of dysentery killed about one thousand people, the plague arrived in Utrecht in August 1624 when eighteen houses were identified and quarantined as “met de peste besmet” (plague contaminated).53 At that time, the regents decided to open up the pesthuis De Leeuwenbergh, where in September, the first deaths attributed to the plague were reported.54 By the time the year ended, about 500 people had died of the plague, around 20 percent of the total annual deaths (2,721) in Utrecht, whose population numbered 30,000 to 35,000 inhabitants.55 With dismaying predictability, the plague recurred every season between 1625 and 1629. In November 1629, ter Brugghen likely died of the disease himself.56

The bubonic plague, which materialized with such alarming regularity, is caused by the bacillus Yersinia pestis, a bacterial disease found in rodents and transmitted to humans by fleas. The infected fleas thrive in relatively high temperatures and in the humid conditions typically found in rats’ nests, woolen cloth, and grain stockpiles. The modern understanding of the plague, however, eluded the seventeenth-century medical and spiritual communities, who looked to other sources for the origins of the epidemic. In their comprehensive review of contemporary sources, Leo Noordegraaf and Gerrit Valk highlighted the common belief that the plague was caused by the sinful nature of humanity, which incited God’s anger. This gave Gods (gift of God), which was a well-known synonym for the plague, was a divine punishment inflicted by natural causes, such as the bad air or miasma that emerged from the humid earth or the pestilentiaal zaat (pestilential seed) that came down from the heavens, bringing sickness and death directly into the vulnerable community.57

In the minds of ter Brugghen and his contemporaries, rotting refuse, stagnant water, and swampy earth gave birth to the rats, snakes, and other vermin that spread the epidemic. This decay was also linked to astronomical phenomena, such as odd conjunctions of planets, the appearance of comets and falling stars, and solar and lunar eclipses. The bile-colored sky in ter Brugghen’s painting provides an appropriately diseased backdrop for an image that speaks to concerns raised by a plague epidemic. An ash-gray atmosphere predominates the right side of the composition and resembles the similarly tinted background in ter Brugghen’s Crucifixion, which Helmut Nickel associated with an annular solar eclipse that occurred in the Netherlands on May 21, 1621.58 Ter Brugghen likely witnessed this event, when the dark disk of the moon obscured most of the sun but for a “ring of fire,” which cast a seemingly supernatural light. The resulting strange coloring of the heavens resembles the eerie light of Saint Sebastian’s execution in ter Brugghen’s painting and points to the sky as a possible source of the disease (fig. 23).

These associations were long-lived, as confirmed by a rare depiction of these phenomena dating to the severe plague years of 1663 and 1664. In a broadsheet on miraculous events, the sky comes alive with harbingers of disease in a scene entitled, “Van de Pestilentie” (fig. 24).59 In the print, a schielijck Vuur (shooting fire) and a gloejende Kogel (glowing bullet) light up the sky, portending the dark scene below, where citizens bury the plague dead and flee into the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam.60

Another enduring sign of the plague found in the skies was the appearance of unfamiliar birds, a connection that had been noted as early as 1602 and as late as the harsh summer of 1664. In ter Brugghen’s painting, a small number of large birds glide ominously in the dusky atmosphere above the parched earth. When along with a fierce northerly wind, a flock of strange fowl appeared in the sky above Amsterdam in the late summer of 1624, the occurrence was linked to the plague, which was intensifying in all parts of the Netherlands.61 Together, the soaring black birds and the menacing sky of ter Brugghen’s painting portend the devastation found on earth.

For ter Brugghen and his contemporaries, the decaying atmosphere fostered the plague and provided the environment for a series of additional earthly misfortunes. The bare landscape of ter Brugghen’s setting includes a small number of frail trees isolated on the horizon line, which may stand as emblems of the ruinous state of the entire scene. In general, the barren backdrop would seem to evoke the economic hardships endured by the Dutch when war resumed with Spain in 1622. Higher taxation, trade embargoes, food shortages, and civic unrest led the Remonstrant preacher Paschier de Fijne (1588–1667) to ask in 1624, “If we cast our eyes over the whole land, do we not see that trade, industry, and the crafts decline everywhere, become lifeless and decay?”62 The anemic saplings also provide further evidence of God’s wrath against human sinfulness. When trees were destroyed by a forceful icy wind that stripped leaves from branches and felled entire trunks in 1665, the same published account that reproduced the image of a fiery sky linked the storm to the plague and divine judgment.63

Peculiar celestial events, strange animal behavior, and overall decay were seen as omens of plague, and bad air was broadly understood as the natural origin of the disease. The means of contracting the disease once it was unleashed remained a mystery, however. Still, certain situations were to be avoided. Since the atmosphere itself was considered a primary source of the “pestilential seed,” the sense of smell made one particularly vulnerable to the contagious agent. To counteract the decaying rubbish that fouled the air with the disease, citizens burned bonfires and made smoldering air fresheners of a variety of spices and herbs, including juniper berries, cloves, rosemary, lavender, sage, mint, and wormwood.64 Pomanders filled with nutmeg, cloves, and cinnamon were kept on the body and bundles of herbs and spices were placed at doors and windows. Even tobacco was thought to provide immunity.65 Smelling the sick or dead could also bring on the disease.

In order to avoid spreading the disease from an infected person, plague locations were quarantined and marked with a bunch of straw.66 Touching a plague victim or objects that had been in contact with the sick or with the miasma that caused the disease was also expected to lead to contamination. Items understood to be highly infectious included linens and wool, paper, and the fur or skins of animals, especially dogs, cats, rabbits, and pigs. The physician Ijsbrand Van Diemerbroek wisely counseled against touching “dirty and greasy” money that had been infected by the “bad air.”67 According to some sources, even the senses of sight and hearing were susceptible because simply seeing cadavers and catching the sounds of the death carts could incite anxiety about the disease that would lead to infection.68

In ter Brugghen’s painting, Irene and her attendant show total disregard of well-established warnings about the transmission of the plague. Both women directly smell, touch, and gaze intently at Saint Sebastian, whose very body reveals signs of the contagious disease. The position of the saint’s extremities highlights the plague’s most obvious symptoms of infection, the painful buboes, and the surface of the skin reveals the resulting trauma. With his right arm extended and his head falling to the side, Saint Sebastian presents his armpit and neck, both places where the inflamed lymph glands associated with the disease appear. Sheila Barker has identified the raised arm as a clear sign of the plague both in Poussin’s The Plague of Ashdod from 1630–31 (fig. 25) and in Ludovico Ferrari’s Saint Dominic Interceding before the Virgin for the Liberation from the Plague from 1635, painted for the city of Padua.69 In his description of the disease from 1624, the Amsterdam physician Jacobus Viverius (ca. 1571/72–1640) identified de Kol (the plague carbuncles or boils) and den Bubo (the buboes) as symptoms of the plague when they appear “aen den Hals, aen d’Oxels, aen de Liessen” (on the neck, in the armpits, and in the groin regions).70 Swollen lumps of flesh along the contours of Saint Sebastian’s body allude to these unambiguous indications of the plague.

The darkening of the skin along Saint Sebastian’s extremities also confirms the presence of the plague. The bruised colors of the flesh along the raised arm and neck, on the chest, and in the legs and feet refer not only to his near-death condition but also to the subcutaneous hemorrhaging brought on by infection when plague-ridden bodies “turned horribly black, swollen, and foul-smelling.”71 This grayish discoloration of the skin, called a “telltale” symptom by Barker, is also evident in no less than four figures in Poussin’s The Plague of Ashdod and in Pietro Bernardi’s Saint Carlo Borromeo Praying among the Plague Victims from the 1610s.72 When this symptom, the peperkoornens (blackening) appeared, along with the pest-buylen (buboes) and the pest-koolen (carbuncles or boils), the Dutch physician Willem Swinnas conclusively diagnosed the plague as he argued in his 1664 publication Peststrijt.73 Actual modern-day occurrences of these signs of the plague resemble the rendering of specific passages of Saint Sebastian’s body in ter Brugghen’s painting (fig. 26, fig. 27, and fig. 28).

According to contemporary doctors, such as Viverius and Paul Barbette (died ca. 1666), the buboes and boils generally appeared after a fairly speedy progression of symptoms, which typically included headache, weakness in the limbs, fever and coughing, sometimes vomiting and diarrhea, and increasing fatigue.74 Medical treatments for these symptoms relied primarily on bloodletting and the administration of purgatives and medicines that brought about sweating to eliminate the plague poison from the body.75 As the disease progressed, the abscessed swellings under the skin were drawn out with strips of linen soaked in chamomile and angelica, a plague spice believed to be miraculous in its effects. These buboes and carbuncles were then lanced and covered with a plaster of red wine, yeast, figs, salt, and saffron.76 Temporal medicines gave way to spiritual remedies as death approached.

Attending to the needs of the body and the soul during outbreaks of the plague had often been the responsibility of the Cellebroeders and Cellezusters or Zwartezusters. These were Roman Catholic lay brothers and sisters, who first came to prominence during the Black Death. By the mid-fifteenth century, the Cellebroeders were well established in Leiden, Amsterdam, Dordrecht, and Utrecht, where they fed, washed, and nursed the victims of plague and other epidemics and buried those who did not survive.77 The Cellezusters, too, provided care to the sick and dying. Their community in Amsterdam, in particular, had close connections with Utrecht, where, in 1475, Bishop David of Burgundy had approved the establishment of their order.78

With the gradual secularization of church property in the 1580s and 1590s, the Cellebroeders lost their homes in Utrecht and were eventually relocated to properties near De Leeuwenbergh, where they continued to perform their traditional roles.79 While their identity as Roman Catholic healers faded, the lay brothers and their secular successors continued to be known as Cellebroeders, and they worked closely with two chief providers paid for by the city during the plague outbreaks of 1624 and 1625.80 In Utrecht, an Amersfoort surgeon named Ernst vande Wal served as pestmeester (plague doctor), which required him to identify victims, to recommend quarantine at home or confinement in the plague house, and to confirm plague deaths.81 In addition, the city paid the salary of a pestziekenbezoeker (visitor of plague victims), who was appointed by the Dutch Reformed consistory and provided pastoral care to the sick and made reports on the health status of patients to the ministers, elders, and deacons.82 In August 1625, Utrecht appointed Abraham Cornelisz. to this post, which he held until May 1632.83 Importantly, the Cellebroeders served two functions not generally covered by the plague doctor or the plague visitor; they looked after the sick sent to De Leeuwenbergh, which by October 1624 was the only facility authorized by the city to receive plague victims, and they buried the dead.84 In the civic ordinances of Utrecht in September 1624 and 1625, the Cellebroeders were named as the only parties allowed to enter plague houses and to remove bodies for transportation to demarcated burial grounds.85 In this regard, one article of their clothing is important to note. As they carried stretchers with the dead through the streets, the Cellebroeders were required to wear dark green cloaks and “banden van wit ende root” (ties of white and red) on their heads for easy identification.86

Ter Brugghen alluded to this very type of headdress by clothing Irene in a similarly rose-tinted white turban. Irene and her helper can thus be seen as undertaking tasks that the Cellebroeders, in particular, assumed during the plague, that is, treating the indigent infirm and burying the dead. Refusing to desert those in need, the women tending to Saint Sebastian, like the caregivers in Utrecht, risked their own lives to serve others.

This resolve to provide aid contradicted a common recommendation made by physicians during plague outbreaks. “Cito, longè, tarde”—flee immediately, stay far away, and be late in returning.87 Avoiding the plague and its victims presented the faithful with a dilemma: abandoning the sick might preserve their health but would also contravene Christian charity.

Although medical authorities recommended flight, religious denominations uniformly encouraged believers to remain with the sick and provide care and comfort.88 How stringently this expectation was endorsed depended on the faith. Most Roman Catholic sources maintained that avoiding infected localities and people was entirely appropriate when done in conjunction with the spiritual remedies of masses, confession, processions, and charitable works. Moreover, according to at least two Franciscan sources, physical flight might prompt the faithful to flee from sin and repent, which would placate God’s anger and end the plague.89 Nevertheless, the most famous acts of Roman Catholic repentance recounted and depicted during ter Brugghen’s lifetime were the penitential processions led by Carlo Borromeo (1538–1484), who resolutely remained in Milan during the pestilence of 1576–77. Indeed, close physical contact with the plague-stricken became the central narrative of Borromeo’s iconography as a plague saint, whose canonization in Saint Peter’s occurred in November 1610, when ter Brugghen was still living in the city.90 Direct ministry to ailing parishioners was also expected of both secular and regular priests in the Dutch Mission area.91 According to a report from 1656, forty priests, who were compared to martyrs, had died from the plague while serving Dutch parishioners.92

The nuanced attitude regarding flight found in Roman Catholic sources was also expressed by those Protestant faiths with a broad-minded view of predestination. These seventeenth-century Protestant theologians, pastors, and religious poets cited Old Testament narratives about fleeing from persecution, starvation, and war as support for escaping from the plague.93 On the other hand, orthodox Calvinists inflexibly objected to flight as an arrogant and hopeless attempt to avoid God’s will.94 Even when authors admitted that the very old, the very young, and foreigners could legitimately flee, they adamantly insisted that most of the faithful should not run away but, instead, remain with the sick and dying.95

The uncompromising opposition to flight by orthodox Calvinists appeared in some surprising sources. In his introduction to a medical treatise by the renowned surgeon David van Mauden (1602), the staunch Calvinist Viverius addressed “de onchristelijke pestvlieders (the unchristian plague-fleers)” with the warning, “Flee anywhere you like. God will find you, unless you are fleeing from your sins.”96 Later, in 1615, Viverius observed gratifyingly that the Amsterdammers who had fled the plague had died, while those who remained in the midst of the epidemic had been saved because “whoever abides in his office, God will abide with him.”97

The debate over flight even appeared on stage in Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero’s Spaansche Brabander. According to Paul Dijstelberge, the character Floris, a church beadle and part-time gravedigger, represents the strict Calvinist position against fleeing the plague.98 In Bredero’s satirical tale, Floris buries the dead without fear because “de gave Gods” will either kill him or not and he has little control over the outcome.

Arguments against flight during periods of pestilence often referred to Psalm 91:2–3, which makes clear in the first two verses that God alone protects his people, “I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust. Surely he shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisome pestilence.”99

These words were the subject of Scherm en Schildt der kinderen Godes, published during the virulent plague season of 1623 by the orthodox Calvinist theologian Reverend Roelof Pietersz. (1584–1649).100 Based on his interpretation of the Old Testament text, Pietersz. argued against fleeing from the plague because it was beneficial to experience the misery and to engage in charitable acts, such as healing and burying. Pietersz. stated that the act of fleeing questions God’s authority and implies that humanity can escape God’s judgment.101

In his meditation, Pietersz. pointed to the purported author of the Psalm, King David, who did not flee but instead did penance for his sins.102 King David’s resolve also figured in the 1656 publication, David’s Credo, by the Amsterdam minister Casparus de Carpentier (1615–1667), which included an account of that year’s plague in Amsterdam and a meditation on Psalm 16. In this Old Testament source, King David flees only to the protection of God as confirmed in verses 1 and 8, “Preserve me, O God: for in thee do I put my trust” and “I have set the Lord always before me: because he is at my right hand, I shall not be moved.”103 Casparus argued God is a better tool for healing than running to a doctor or into the countryside.104 King David put his faith in God, and contemporary sufferers should, too.

King David represented a stalwart source for those who stayed behind to serve, such as the city appointed officials and the Cellebroeders who cared for plague sufferers during epidemics. In ter Bruggen’s painting, too, Saint Sebastian and Irene did not flee, but remained to heal and convert.

Significantly, King David’s relationship with God was defined by the plague as related in II Samuel 24:10–14 and I Chronicles 21:8–13. When he offended God by ordering a census of his soldiers, King David was offered one of three punishments, and he chose the plague instead of famine or war. After three days of the pestilence killed 70,000 Israelites, King David begged for mercy, and God brought an end to the epidemic.105

Although infrequently depicted in art, King David’s decision to inflict the plague on his people appeared in illustrated Bibles and in such rare works as the painting from 1635–40 by the Haarlem Roman Catholic painter Pieter de Grebber (fig. 29).106 To underscore King David’s leadership when he suffered along with his people during the plague, ter Brugghen also included a pictorial reference to the Old Testament king. The brilliant red and gold fabric on which Saint Sebastian strangely sits refers to King David and to the community of Utrecht.

The rich brocade pattern of this cloth resembles the well-known similarly decorated ecclesiastical robe of David of Burgundy, bishop of Utrecht from 1456 to 1496, which was preserved in the Roman Catholic clandestine church of Saint Gertrude by 1626 (fig. 30).107 As early as 1620, the recognizable cope had served as the costume for Pilate in ter Brugghen’s Crowning with Thorns.108 His likely teacher, the influential artist Abraham Bloemaert, had also adopted the liturgical garment for the figure of the magus Melchior in several versions of the Adoration of the Magi, including a work from 1624 (fig. 31).109 The general pattern of the cope of David of Burgundy also appeared in contemporary paintings of the Old Testament figure of King David by Honthorst in 1622 and by ter Brugghen in 1628 (fig. 32 and fig. 33).110

Although ter Brugghen did not explicitly reproduce the design of the famous cope in his painting of Saint Sebastian, the pomegranate pattern of his version closely resembles the carefully preserved item. Its use here, then, directly acknowledges the locally revered liturgical vestment of David of Burgundy and suggests an allusion to the similarly named King David and his refusal to abandon his people to the consequences of the plague.111 Furthermore, the pomegranate in the pattern was a well-known symbol of immortality that appropriately speaks to the saint’s martyrdom and eternal life.112 The standard liturgical use of the cope also supports its association with Saint Sebastian in that it was worn during Sunday High Mass and in feast-day processions, when its red color symbolically recognized the sacrifice of martyrs. Not least, the cope was often used for such outdoor ceremonies as burials, the very act Irene and her helper have come to accomplish in ter Brugghen’s painting.113

As an ecclesiastical vestment with specific connections to the rich history of Utrecht Roman Catholicism in general and to the elevated role of David of Burgundy in particular, the famous fabric in ter Brugghen’s painting suggests a commission originating with a Roman Catholic clandestine church.114 As Xander van Eck has demonstrated, however, no historical documentation connects ter Brugghen’s paintings to the Roman Catholics in Utrecht.115 Yet, ter Brugghen depicted not only a traditional Roman Catholic saint but added the post-Tridentine figure of Irene in a setting redolent with references to plague conditions experienced by the citizens of Utrecht in the 1620s. As a healer who did not flee, Irene serves to inspire contemporary caregivers. This significant content suggests a commission from an individual or institution providing care to plague sufferers without restricting the painting’s message to any one religious denomination.116

Ter Brugghen’s own religious orientation is unknown. Although Benjamin J. Kaplan has noted that the artist was married in the Dutch Reformed Church, and his children were baptized by Contra-Remonstrant ministers, he was not documented as a member of any specific denomination.117 Instead, ter Brugghen’s personal religious conviction was possibly unaligned, as was the case for nearly one fourth of the population in Utrecht who had moved away from Roman Catholicism but hesitated to fully accept orthodox Calvinism.118 These so-called Libertines retained some traditional devotional practices from the past and also recognized individual agency, such as Irene’s actions in the life of Saint Sebastian or the response of the Cellebroeders and other resolute caregivers, as a means of connecting with God, as declared by the newly established reformed faiths.

In multiconfessional Utrecht, Libertines lived and worshipped alongside Mennonites, Lutherans, Roman Catholics, and a diverse group of Dutch Reformed Protestants. Ter Brugghen’s painting of Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene would seem to have provided comfort to all of them.119 However, its subject, incorporating as it does the iconographic tradition of Saint Sebastian’s intercessory role during time of plague, clearly ties the artist’s depiction to the faith of Rome, a religious conviction still shared by about 40 percent of the Utrecht population.120 More specifically, the introduction of Irene recognized the reforming spirit that broadened the appeal of Saint Sebastian to an audience of faithful caregivers who did not flee but remained to serve.

In his painting of Saint Sebastian and Irene, ter Brugghen achieved a balance of composition and content not evident in the works of his contemporaries. The diagonal alignment of the injured saint and the two women who have come to rescue him creates a powerful equilibrium. As they reach out to release the saint’s hand and remove an arrow from his side their movements contrast potently with the immobility of Saint Sebastian’s body and the stillness of the setting.

To sum up, ter Brugghen alludes to contemporary conditions experienced during plague outbreaks in order to communicate directly to his community during a time of hardship. The artist successfully unites the static figure of Saint Sebastian—embodying the Roman Catholic belief in his intercessory powers—with the actions of Irene and her assistant—who speak to the Protestant emphasis on the responsibilities of the individual. In this complex pictorial presentation, ter Brugghen brought together traditions that continued to nurture the spiritual needs of plague victims, while addressing the contemporary conditions of the plague and the faith-inspired response of caregivers.