The anamorphosis decorating the top of Samuel van Hoogstraten’s perspective box in London has long puzzled art historians; some prescribe a viewing position at the bottom right of the image, which only corrects some of its distortions, while others have dismissed it as a failed attempt. But rather than being a failure, the anamorphosis instead requires a corrective apparatus to mediate its viewing: either a concave lens or a viewing aperture originally mounted atop the box. This article argues for the necessity of such an apparatus and analyzes its implications in the context of the box’s exterior decoration and ideas expounded in the artist’s writings.

Samuel van Hoogstraten’s perspective box in the National Gallery, London, is the finest example of six surviving seventeenth-century Dutch perspective boxes.1 Each box makes use of anamorphosis, a technique by which an image is skewed so that the optimal viewing perspective is at a severe oblique angle to the picture plane, in order to make the interior look like a large space when seen through a peephole. Van Hoogstraten’s box is about two feet high and wide and three feet long, and it is open on one of the long sides in order to let in light (figs. 1–3).2 The inside is painted anamorphically to show a large domestic interior when seen through peepholes at either end of the box. There are multiple illusionistically painted doorkijken, or through-views, that offer glimpses into additional rooms and hallways connected to the central vestibule. Yet when viewed from the open side, the interior appears a jumble of incongruent perspectives awkwardly stretched and abutting one another.

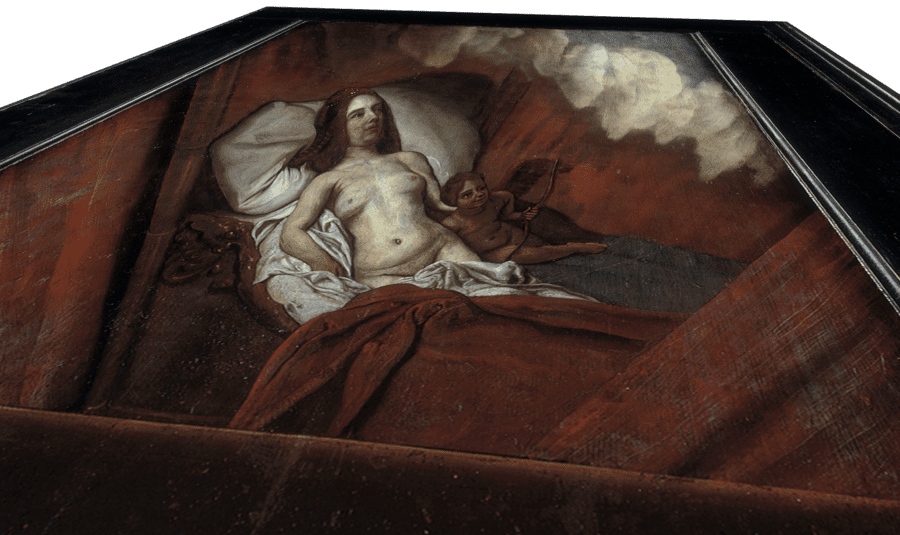

Painted allegorical scenes decorate the box’s exterior, which is quite different in character from the inside. The lateral panels feature allegorical representations of Seneca’s three motivations for art: Amoris Causa, Gloriæ Causa, and Lucri Causa (for the purposes of Love, Glory, and Money, respectively; figs. 4–6).3 On the top of the box is an anamorphically stretched image of a nude female figure—identified by scholars variously as Venus, Erato, or Danaë—lying in bed beside Cupid (fig. 7).

The exact nature of this anamorphosis has not been concretely established, although it has often been dismissed as unsuccessful due to difficulties in satisfactorily resolving the image. The present article will demonstrate that, far from being a failed attempt, the image on the lid employs a heretofore unrecognized variety of anamorphosis with significant implications regarding its viewing. I offer two possible correctives to the image atop the box, both of which posit the existence of a now-lost viewing apparatus that would have been attached to the box in its original form.4 I will explore the implications of these attachments, expanding upon Celeste Brusati’s proposition that, via pictorial examples, the box demonstrates optical principles that van Hoogstraten would later explain in his treatise on art, the Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst: anders de zichtbaere werelt (Introduction to the Academy of Painting: or the Visible World), 1678.5

The interior of the box, its program, and its construction have been discussed at length by Brusati, Thijs Weststeijn, Susan Koslow, David Bomford, Herman Colenbrander, and others.6 While Bomford has expertly explained the perspectival mechanics at play, interpretations of the interior of the box are still much contested; it has been postulated as a simple trick of the eye, a demonstration piece of optical experiments, a thematic meditation on love’s generative capacity, a veiled brothel scene, and an emblematically dense marriage gift from van Hoogstraten to his wife.7 In this article, I leave aside the interpretive questions raised by the imagery of the box’s domestic interior and focus primarily on the box’s exterior, with particular attention to the lid.

The image atop the box has always been treated as a straightforward anamorphosis. Scholars who have considered the matter have postulated a viewing position “from a point somewhere at the back and to the right of the box.”8This has been the general consensus, as it corrects the perspective of the head of the female nude (fig. 8). Yet from this angle the head remains too large for the body, and the depicted space does not resolve into a coherent perspective. Only a few scholars have noted the strange proportions and angles that result from this supposed correction. Bomford describes it as:

. . . a straightforward trapezoid anamorphic projection which is observed correctly by the observer approaching the right-hand end of the box. However, the centre of projection—the point from which it must be viewed—is off-centre and does not quite correspond with the viewer’s approach to the peephole. It is not, in truth, an entirely successful anamorphic image: there seems to be no point from which it is convincingly corrected.9

Others have repeated the ideal viewing position from the bottom right of the image, though the resulting inconsistencies are rarely mentioned. Yet it seems implausible that van Hoogstraten would have failed to produce a very basic anamorphosis on the exterior of the box while having executed a singularly complex set of interlocking anamorphoses for the interior.

Bomford posits that the image was constructed empirically, due to a lack of drawn lines, and this may well be the case.10 But empirical construction does not preclude success, and lines within the image indicate an underlying perspectival structure. The depicted space contains bedposts and draped curtains which fall in lines that should appear more or less vertical once the anamorphosis is viewed from the intended position—but when viewed from the bottom right they form angles that are almost perpendicular at their extremes. The lines instead radiate from a point at the center of the image’s lower edge (fig. 9), an area that falls just behind a brown strip about two inches wide that van Hoogstraten painted across the bottom of the panel. The strip, neither anamorphic nor illusionistic, has been entirely unremarked upon in scholarship on the box, but it is from a point just behind this brown strip that the image coheres.

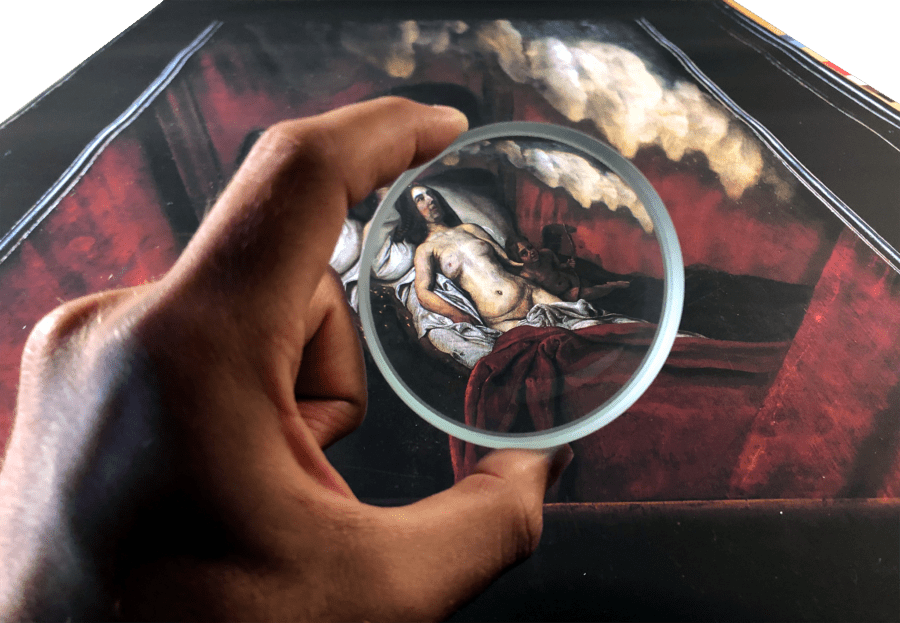

I offer two possible modes of correction for the lid, both of which account for the presence of the brown strip. Both assume that van Hoogstraten’s box originally supported a viewing apparatus in the center of the strip or immediately behind it, which would have mediated viewing of the lid.11 The first possibility is that van Hoogstraten used a large concave lens that would have formed the corrected image in its entirety before the viewer. The second possibility is simpler and parallels the peepholes already present on the box. If some sort of viewing aperture had been attached so that the viewer’s vision was directed and limited, then the eye would have been fixed at a single point from which the anamorphosis was corrected and the field of vision limited to prevent perspectival dissonance. Through an aperture or lens, the brown strip is almost entirely hidden from view, visible only at the very margins, and whatever might be visible is made unobtrusive by its wooden coloring.12 In either case, the necessity of a viewing apparatus for the anamorphosis has significant implications for the interpretation of the box.

First, the lens.13 Numerous sources—including van Hoogstraten himself—recommend the use of lenses as an aid to artists. In Magia Naturalis (1558), Giambattista della Porta advises that by using a lens an artist might “describe compendiously” large and wide things:

[B]y opposition to a Concave Lenticular, those things that are in a great Plain are contracted into a small compass by it; so that a Painter that beholds it, may with little labour and skill, draw them all proportionable and exactly[.]14

In Book 7 of his Inleyding, van Hoogstraten advised painters to make use of lenses and the camera obscura, which could condense a larger scene to give a better sense of its general coloring and tonalities.15 The capacity of the lens to collapse wide views within a small frame was thus vital to its use as an artist’s tool. A concave lens mounted at the center of the brown strip could likewise condense the painting atop the box, thereby demonstrating experimentally the capacities of the lens described textually by both van Hoogstraten and della Porta (figs. 10–13).16

Magia Naturalis and other period texts on optics further discuss how lenses might “make an image seem to hang in the air.”17 Della Porta enumerates the various ways in which one can place lenses in front of objects such that their images appear to float before the viewer.18 When a concave lens is placed above and in front of the image atop the box, it produces a similar effect, but unlike della Porta’s object reconstituted in a lens placed directly in front of it, van Hoogstraten’s painting would be placed obliquely before the lens. The corrected image would then exist only within the lens, as if conjured from nothing. The lens’s constitutive capacity is thus twofold, not only refiguring the anamorphosis in a comprehensible manner but also making the now-coherent arrangement of colors “float” in the lens before the viewer. This mounted lens would ideally have been a few inches in diameter so that one could view it from a distance.19

Kepler, Descartes, and other seventeenth-century natural philosophers emphasized the mechanical nature of the human eye, describing it as a dark chamber into which an image of the outside world is projected, via the biconvex lens of the crystalline.20 They conceptualized the eye as a miniature camera obscura and consequently noted its mechanical fallibility.21 Kepler notes that the act of vision is both subject to deception and deceptive in and of itself.22 Van Hoogstraten himself calls attention to the fallibility of sight in Book Seven, Chapter Seven of the Inleyding:

[T]here is nothing more easily tricked than sight. But I say that a painter, whose work it is to trick sight, should also have enough knowledge of the nature of things that he fundamentally understands by what means the eye is tricked.23

Brusati has argued that the interior of van Hoogstraten’s box was an affirmation of this idea, in that it revealed “how the eye is deceived both by the painter’s art and by the act of seeing itself.”24 Through its deception, the views seen through the peepholes call attention to the fallibility of vision and the mechanical nature of sight.

In two articles on modern uses of anamorphoses in art, Daniel Collins notes how the anamorphic image offers the viewer an active role in the creation of the image and calls attention to the act of seeing. Collins calls the viewer of anamorphoses the “eccentric observer,” or an observer “who literally stands apart and is self-aware of the process of seeing.”25 This “stand[ing] apart from seeing” is even more literal in an anamorphosis corrected by a lens, because the point at which the image is resolved (i.e., in the lens) exists outside of the eye of the viewer. While Kepler and others explained the eye as lens in their writings on optics, van Hoogstraten demonstrated it experimentally. A lens mounted atop the box would have provided a visual experiment that the viewer could compare with the illusions provided through the peepholes on either side of the box. In the juxtaposition of peephole and lens, van Hoogstraten called attention to the mechanical nature of vision by showing that the eye situated before the peephole is subject to the same deception—and undergoes the same constitutive image-making process—as the lens atop the box. But unlike the peeping eye, which had to look around inside the box, the lens would form the image in its entirety so that the viewer could view it from a remove. Via lenticular proxy, they could see seeing.

One problem arises from a lens-based solution: the lines of the hanging curtains that should be straight and vertical become slightly curved in the lens, especially at the margins. Yet this does not eliminate the lens as a possibility; in his Inleyding van Hoogstraten states that due to our seeing in the round, straight lines often appear curved: “[A]s you can see standing before a building or a church, not only do both the ends of the walls but also the towers slope away from us, [becoming] foreshortened and diminished.”26 Van Hoogstraten continues that it would be silly to represent such curves unless the intention was for the work to be seen “from very close up.”

A second possible corrective avoids the distortions of the lens and coincides with this conception of a distorted work meant to be seen from “from very close up.” Rather than a lens, Van Hoogstraten may have mounted a sort of peephole atop the box, replacing the lens with the eye itself. This could have been as simple as a mounted ring but would have functioned better if it blocked out the surrounding area so that the eye could not see around it (figs. 14–18, video). By restricting the viewer’s mobility and use of both eyes, a peephole limits the viewer to static monocular depth cues, most of which can be counterfeited on a flat surface. Furthermore, as vision is limited to a small portion of depicted space at any given time, the left-most part of the image does not require the same vanishing point as the right-most part. By creating different perspectives that fan out radially from the aperture, van Hoogstraten could simulate the experience of looking around oneself at an image in the round, albeit through a peephole. As a viewer moves their eye from one side to the other, incongruous perspectives become resolved as an accumulation of aggregate views seen through an aperture.

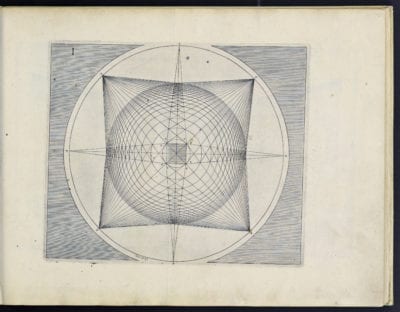

A figure from Hans Vredeman de Vries’s Perspective illustrates the idea of a mobile eye at the center of a changing perspective (fig. 19).27 Vredeman’s diagram depicts multiple distance points that result from moving one’s eye around a horizon, with a view marked every ninety degrees of the circular horizon.28 Citing Vredeman’s diagram, Walter Liedtke has argued that Carel Fabritius’s panoramic View in Delft was originally mounted on a curved support and displayed within a triangular perspective box (fig. 20).29 While Fabritius’s view may have originally been curved in order to surround the eye of the viewer, van Hoogstraten’s image is projected anamorphically so that it too surrounds the viewer. As a result, it has points of view that are meant to be seen from angles that vary by nearly ninety degrees from the left-most to the right-most. This is precisely why the concave lens works as another corrective: it collapses the expanded view around it into a smaller area, and it does so from the prescribed point of view at the center of the arc. The tacit principles behind this construction are stated in the Inleyding: “[W]e see around us with our eyes, and therefore no straight line can be drawn, which is at all points equally near to our eyes; but [we can draw] a curve, like the outline of a circle, of which the center is in our eye.”30

The use of an aperture for facilitating an eccentric viewing position is documented in the work of at least one of van Hoogstraten’s contemporaries. In 1667 and 1668 Jan van der Heyden painted two views of the Town Hall of Amsterdam (figs. 21–22). Though the points of view are very similar in both, the perspectives are formulated differently. One is fairly straightforward linear perspective, while the other is projected such that the Town Hall becomes distorted toward the top and left of the painting, and the cupola appears distended. A letter to the purchaser of the painting—no less a figure than Cosimo de’ Medici—has survived, describing its prescribed viewing: “One must look at it from one exact point, through a metal instrument attached to the frame.” 31 The casting of viewer as “eccentric observer” not only corrects the distortion of the cupola but also more effectively envelops the viewer in the space of the Dam Square. The Town Hall, seen from below, towers over the viewer and expands around them to the left. One has the sense that he or she is at street level alongside the previously diminutive figures, who now appear much larger to the repositioned viewer.32 Such a precedent lends credence to the possibility of a corrective apparatus mounted atop van Hoogstraten’s box, be it a lens or an aperture.33

There is a third method by which the image could be corrected, which is perhaps the least likely. A convex mirror mounted above the dark brown strip could function much like the lens, but it has similar problems of distortion, among other disadvantages.34 Unlike the lens, the mirror would need to be viewed from the opposite end of the box. The image would be reduced in size in the mirror, and the required viewing distance compounds the problem, making details difficult to see (figs. 23–24). Still, cylindrical mirrors were often used to correct anamorphoses, discussed in perspective treatises, and mentioned by van Hoogstraten in Book Seven of the Inleyding.35 Though less effective than the lens and peephole, it corrects the distortions of the anamorphosis adequately.

It is also possible that the lens, aperture, and/or mirror were removeable components that could be mounted interchangeably, merely set atop the brown strip. The components could have even been handheld, requiring viewers to play with the positioning to “solve” the image as if it were a sort of visual puzzle (fig. 25). This falls in line with Sven Dupré’s characterization of ad hoc optical demonstrations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in which “various and different optical design elements (lenses, mirrors, apertures) were brought together and assembled in diverse ways” in order to produce different optical effects.36 Were this the case with the lid of van Hoogstraten’s box, it would demonstrate more explicitly the interchangeability of the eye (via the aperture) and the lens, while also putting into relief differences between the various viewing experiences. It would thus create a more participatory experience that forces the viewer to study and investigate the optical principles at play and to consider their own relative position within this system of seeing.

* * *

The present study has heretofore dealt largely with the mechanics of the London box’s lid, but the mediated viewing of the anamorphosis also has implications vis-à-vis its subject matter and its place in the larger exterior program. The exterior walls feature allegorical representations of Seneca’s three motivations for art: Amoris Causa, Gloriæ Causa, and Lucri Causa (figs. 4–6). Each representation includes an artist with his back to the viewer, working in a dark, ambiguous space filled with billowing gray clouds. There is a progression implied in the images, beginning with Amoris Causa, the side from which the anamorphosis would have been viewed and one of the two sides with peephole views of the interior. The artist on this panel is sketching with red chalk on paper, practicing the art of drawing (teykenkonst), which is the subject of the first book of Van Hoogstraten’s Inleyding and the foundation of all other arts. It is the originary art, just as love is the first benefit of art.37 Van Hoogstraten (paraphrasing Seneca) explains that a love of art precedes the benefits of earnings and honor, and this face of the box is thus the logical starting point.38

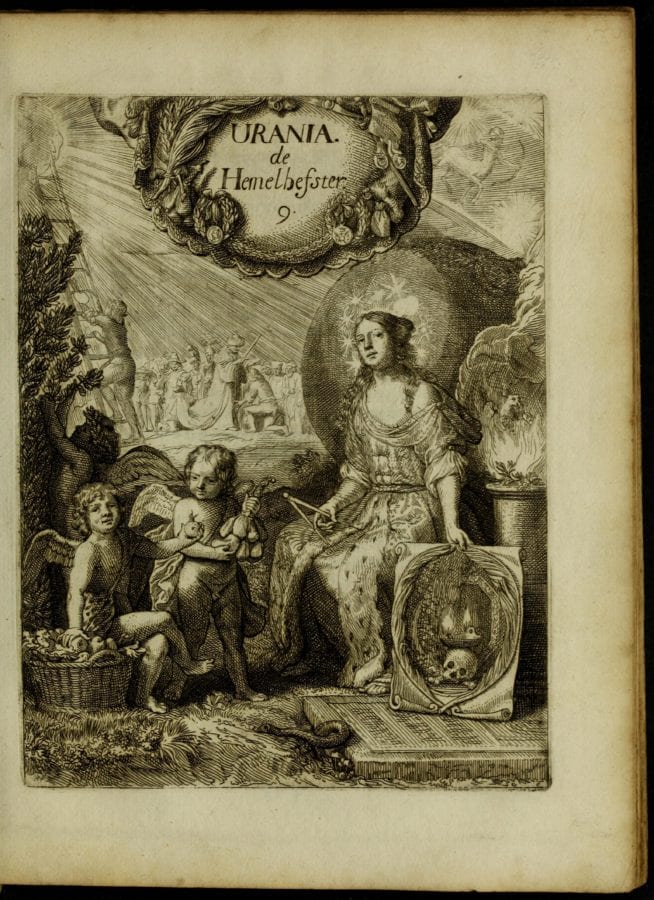

A putto directs the draughtsman, gesturing both toward his subject and to the peephole at this end of the box. Behind him, a small opening in the clouds reveals a small sliver of landscape, the coloring of which suggests dawn. The artist’s subject is a combination of Natura and the muse Urania.39 Natura is identifiable by her many breasts, and she is a suitable subject for the young pupil who, van Hoogstraten advises, should have not only a love of art but also a love of investigating and portraying “nature in all her peculiarities.”40 In a clever reversal, van Hoogstraten shows an artist working naar het leven (after nature) in a manner paradoxically uit den geest (from the imagination or spirit).41 Urania is the muse of the final book of the Inleyding concerning the rewards of the artist, and the book’s title plate shows her surrounded by objects and scenes that suggest the wealth and praise that await the artist (fig. 26).42 On the box, however, Urania is identifiable only by the globe and stars above her head, with the expected rewards reserved for the other faces of the box.43

In Gloriæ Causa, on the opposite end of the box, a putto bestows a gold chain and crown of laurels upon the artist, granting some of the rewards promised by Urania. The putto’s gesture, again, points toward the peephole. The painter is more ornately dressed than his counterparts elsewhere on the box, probably denoting a courtly appointment.44 His painting appears in its early stages, and it is unclear whether he is in the process of painting or underdrawing.45 As before, the clouds open up beside him to reveal a landscape, but here much more is visible, and the light is no longer crepuscular in nature.

In Lucri Causa, the largest panel of the three, a round-faced, wingless putto reclines against a cornucopia that he holds as riches spill from its opening. The figure is a young Plutus, god of riches and wealth.46 He looks out at the viewer holding a scepter and wearing a crown, markers of his prosperity. The painter, no longer directed by putti, is placed further from the viewer, with his back turned. His hands are concealed; no brush or maulstick is visible; and no model sits before him. The completed image of a noblewoman on his panel may indicate that he is, in fact, finished painting.47 The clouds behind him open up to reveal still more landscape and a bright blue sky.

The box’s exterior implies a progression from love, to glory, and then to wealth. This order is the same as given by Seneca and initially repeated by van Hoogstraten in his Inleyding, although he later switches wealth and glory when discussing each in more depth.48 The panels illustrate in sequence an artist aided by putti to one who is independent, from drawing to painting to finished work, and from concealment to revelation of the landscape, which likewise proceeds from dawn to day.49 There may even be a progression in the artists’ ages, if one can judge by the draughtsman’s unkempt hair and the other artists’ increasingly straight, more groomed tresses.50 Like van Hoogstraten’s Inleyding, the exterior program of the box offers a path for the artist to follow, and just as in the Inleyding, he begins with the basics of drawing and instruction and concludes with fortunes, fame, and wealth.

The lid’s painting is largely independent from the program of the exterior walls. Ignoring the unique anamorphic projection of the image, there is also no painter depicted, and the space is a recognizable physical one: a bedchamber. While it, too, includes clouds above the bed and a putto figure, the putto’s skin is of a more golden tonality, his wings red rather than white, and his face more boyish and proportions more delicate than the robust putti of the other panels. His bow further distinguishes him specifically as Cupid.51 Cupid gives clues to the identity of the nude female figure, who has alternatively been called Venus, Erato, and Danaë. Venus is the most common attribution, but her associations are rather general; and in any case, it is not unlikely that van Hoogstraten intended his figure to have multiple associations, as does the Urania/Natura figure on the side of the box.

Herman Colenbrander and Jan Blanc put forth an identification as Danaë, citing the upward, expectant gazes of the figures and the coins spilling from the cornucopia on the side of the box.52 The story of Danaë is apropos in that, as Karel van Mander tells us, “[Acrisius] had a secret chamber constructed from copper underground beneath his room, in which he shut away [Danaë] . . . so that she could not be impregnated by anyone.”53 What’s more, once Danaë was impregnated by Zeus, her father “enclosed the mother and child . . . in a wooden chest, shut and well-sealed.”54 The resonances of the perspective box and its lid with an enclosed wooden box and a chamber hidden from view are difficult to ignore. If it is indeed Danaë, the exaggerated point of view places the viewer in the position of Zeus, in the form of a shower of gold about to impregnate Danaë: note the conspicuously exposed lower abdomen. The perspective from above, which is more pronounced when viewed through an aperture, does indeed give the impression that one is looking down into a sealed-off underground chamber, and even down into the box itself. While Acrisius hid Danaë from view by enclosing her in an underground chamber and then in a wooden box, van Hoogstraten has hidden her perspectivally, only to be revealed by those with the knowhow to visually enter her enclosure.

Brusati offers another reading of the figure as Erato. She cites van Hoogstraten’s Fourth Book of the Inleyding, in which he explains that Venus sent Cupid to be eternally joined with Erato, whom he later calls a “Venus among the Muses.”55 This reading is compelling in light of a passage in the Inleyding in which the artist addresses Erato directly, asking her to “open to us the inner chambers, where the ladies in waiting prepare to dance, or sigh out of love in their elegant bedchambers.”56 Erato, as the fourth of the nine muses that structure each book of the Inleyding, acts as a guide on the path of the enlightened painter, a path imagined as a structure of rooms and chambers into which the muse gives access. In the context of the box’s lid, Erato draws the viewer into her chamber with both erotic and perspectival enticement, and her role as the Minnedichster, or love poetess, links her to Amoris Causa.

In fact, all three possible identifications hold amorous connotations linking them with Amoris Causa on the exterior. But besides love as a motivation for the artist, the erotic positioning of the figure in a bedchamber and the experience of viewing her from above through a peephole or lens further serve to arouse desirous feelings in a presumably heterosexual male viewer. But this was hardly mere smut; such an arousal relates to van Hoogstraten’s theories on the passions and bridges the sensory world of the purely visual with the interior world of the viewer. Van Hoogstraten—following Franciscus Junius—argued that great works of art ought not only to be beautiful but should also “have a certain moving-ness in them, which has power over its viewers.”57 In invoking this capacity for inciting movement (beweeglijkheyt), van Hoogstraten speaks of stirring both emotional and physical reactions, as physical movements were seen as an analogue to internal feelings.58 The box’s moving power over its viewer is compounded by the fact that it demands a literal movement of the body in order to accommodate the strictures of its viewing apparatuses. Once pulled into the reclining nude’s crimson chamber, the viewer’s inner passions were likewise stoked.59

The clouds above the Venus figure lend the whole scene an air of ephemerality; it is always revealing itself or in danger of receding back into clouds. Indeed, the image only coheres when seen through the corrective apparatus of a lens or aperture, and it dissolves back into streaks of color on a flat surface once the viewer leaves the prescribed viewpoint. On the exterior panels, with each progression of the artist and his artwork, the clouds part to reveal more of an increasingly illuminated landscape. The artist’s environment on the exterior walls is not a heavenly realm filled with light, but rather an obfuscated space composed of clouds and umbrae. The painter occupies an obscure and invisible world, which he reveals through his art. The culmination of this revelation is atop the box, where the obfuscation lifts to reveal the bedchamber of the Venus figure, who arouses the inner passions of the viewer.

The box as a whole is then not only about deception but also about revelation: the revelation of seeing itself, or of seeing clearly for the first time. Van Hoogstraten’s trompe l’oeil paintings are ostensibly meant to be seen as something other than paintings—a cabinet door or a letter rack—before the realization of the painted surface. This tradition was established in antiquity with Pliny’s story of a contest between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, in which Zeuxis created a painting of grapes so convincing as to deceive birds, and in response Parrhasius painted a curtain so lifelike that it fooled Zeuxis. Van Hoogstraten, in addition to retelling the story in his Inleyding, had his own sort of Zeuxis tale, wherein his paintings fooled the Emperor Ferdinand III, leading to his decoration by the Emperor.60 Such trompe l’oeil paintings start with a pretext of deception that gives way to the realization of their fiction upon closer inspection, and therein lies their amusement. Conversely, van Hoogstraten’s box begins with its identity fixed as an object composed of painted surfaces that then gives way to an illusion, thus foregrounding the deception itself. One sees this inner bedchamber (or the Dutch interior inside the box) in spite of what one knows is merely patches of paint on a wooden panel. In the exterior panels, the revelation of the landscape in concert with the progression of the artist illustrates the revelatory power of the artist’s work, a claim reiterated by the putti who gesture toward the peepholes on either end of the box. The young Plutus, too, gestures with his scepter, pointing upward toward the lid of the box, where the reclining Venus/Danaë/Erato awaits viewers in her perspectivally hidden bedchamber.

In a self-portrait print at the beginning of the Inleyding, Van Hoogstraten presents himself seated in a chair in a room filled with swirling clouds (fig. 27). Beside him is a statue of Atlas, carrying an orb labeled the “Visible World.” Clouds rise behind him and shroud a second, barely perceptible orb: the “Invisible World.” 61 Van Hoogstraten’s naming of Visible and Invisible Worlds in his Inleyding and self-portrait posits that the artist claims access to both, placing him in the privileged position of a preternatural medium, a sort of necromancer endowed with vision and knowledge beyond the visible world and the unique ability to render that knowledge through painting. In the title plate of Book Seven of the Inleyding—concerning light, shadow and perspective—the muse Melpomene demonstrates a similar knowledge of the Invisible World (fig. 28). Crowned with a halo of eyes, she holds a burning lens with which she concentrates the light of the world forward in the form of a cone of light, echoing the cones found in the perspectival and optical diagrams of Vredeman, Descartes, and Kepler (fig. 29). Melpomene—as Van Hoogstraten’s muse of light, shadow, and perspective—takes her lens and “creates pleasure in that which diminishes or magnifies, darkens or illuminates, emerges or gets undone.” 62 In his treatise, self-portrait, and especially in his perspective box, Van Hoogstraten lays claim to these powers of the demigod Melpomene, using his representational prowess to reconstitute an obscure and inaccessible world into painted allegories and interiors. He shares this power with his audience not only by presenting them with the anamorphic image revealed through a lens, aperture, and/or mirror—demonstrating for them the mechanics of vision itself—but also by inviting his viewers into shrouded and hidden chambers, leading to a knowledge that will unveil the visible world.