Reconstructing historical paintings—remaking them step-by-step with materials that approximate those used at the time—has become increasingly important as a means to investigate artistic practice. Through the sensory activity of reconstruction, a painting can be studied as a process, building it up from scratch and going through motions and stages that are similar to those the painter used. Since final paint layers obscure grounds and earlier layers, reconstructions are crucial for investigating the nature and role of colored grounds within the whole of a painting. This paper demonstrates this application through two case studies. Researchers can use the observations that have emerged from these reconstructions as a framework to connect the social history of making to formal analysis and the study of technique.

When we look at a seventeenth-century painting in a museum, we look at the sum of the paint layers applied by the artist, plus hundreds of years of exposure to light and moisture, and sometimes the visually impactful results of human attempts to preserve the object through restoration or adjust its appearance according to the fashions of their time. Deconstructing this amalgam of effects into its individual parts is an important challenge for art history, and it is crucial for describing evolutions of style and technique. Step-by-step reconstruction of the brushstrokes and layering applied by the artist can generate a greater understanding of the original qualities of an object and the trajectory of its making. Reconstructions are a creative process, allowing us to come as close as we can to what an artist felt with their hands and saw with their eyes while working—and thus what prompted their subsequent creative steps.

In reconstructing paintings, we use our own bodies as a research tool, which means that we need to consider our own positionality. Our experiences and perspectives influence how we use our bodies and interpret our observations. Maartje Stols-Witlox is an art historian and paintings conservator who, through the execution of several earlier reconstruction projects, has assembled considerable expertise in the stretching of canvases and the grinding and application of paints. Lieve d’Hont has a similar educational background—trained in art history and with a degree in paintings conservation—but the project discussed in this paper is her first extensive reconstruction-based study. Maartje and Lieve have both worked as conservators of seventeenth-century paintings in museums and private institutions before embarking on their respective research trajectories.

To honor and clearly acknowledge the role of the researcher as an investigative tool, it is common to choose a personal perspective in writing about reconstructions. Below, our descriptions will use either “we” or the given name of the researcher whose observations are discussed. This style of formulation is not unique to reconstruction-based research. It characterizes the application of sensory methods across various academic domains and has been adapted from auto-ethnographical approaches developed within the social sciences.1

In this paper, we not only share results from our reconstruction experiments but also reflect on the potential and the limitations of reconstructions in the context of paintings examination. We also share our thoughts about how to integrate reconstructions within the broader array of methods that art historians, conservators, and conservation scientists use to investigate paintings.

The two main case studies, which stem from the research interests of the Down to the Ground project team,2 exemplify the varieties of reconstruction design and typology employed in the field. They demonstrate the functions of different levels of historical accuracy in their choices of materials and visual similarity to original paintings. We argue that reconstructions are powerful tools for connecting visual observations about style and technique with technical and scientific analysis, thus increasing the depth of our understanding of paintings and painter’s practices. This explains their relevance for art historical and technological research. There is an increasing need for strategies that allow us to make such connections. The rapidly growing role of non-destructive scientific imaging methods in art history, such as macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF), X-ray diffraction (XRD), multispectral imaging, and so on,3 provides data on materials and layers hidden from view in the final painting—yet interpreting such data is a difficult challenge, as the role of these materials may not be directly obvious in the finished painting.

The first case study demonstrates how reconstructions can provide insight into the qualities of the early stages of a painting. While one might assume that covered-up stages do not play a significant role in the final image, we demonstrate otherwise with the example of a painting executed on an exceptionally dark ground: Boy Sleeping in a Barn by François Ryckhals (see fig. 5). By adopting reconstruction as a focused method, we can reverse-engineer the painting and gain a deeper comprehension of the image we see in the museum. Only by investigating techniques as a process can we understand the sensory dimensions of making, the things an artist felt with their hands and saw with their eyes while working. Through reconstruction, we can tease out more material information from this puzzling little painting and close some of the gaps in our understanding of what motivated Ryckhals in his selection of materials and methods. 4

The second case discussed in this paper concerns a type of canvas ground that was popular in the seventeenth-century Netherlands but is not well understood today. This ground consists of two layers: a first reddish layer of ocher and other earth pigments, covered by a second gray layer based on lead white. We discuss where and when this two-layer ground was used by artists and test the plausibility of two different explanations for its popularity. In this case, we also investigate through reconstructions the chances that a known aging phenomenon in oil paint—lead saponification—would have impacted the tone of this type of ground. This case has been chosen to illustrate how even reconstructions that do not mimic the exact brushstrokes and imagery of a painting can help answer questions that are central to art historical inquiry—in this case about its visual qualities and tonality.

Together, these cases exemplify the variety of questions that reconstructions can address. They show that new insights can be generated exactly because reconstructions require doing, a process that forces decisions. Such decisions are the result of a researcher’s practical, personal choices. As will become clear from this essay, reconstruction researchers investigate with multiple senses and rely on their own practical experience. This sets reconstructions apart from many other art historical methods that employ mainly vision and intellect: here, the researcher uses their muscles to grind and brush, feels the resistance and flow of the paint, and actively builds layer over layer, thus observing the effects of superpositions. How this process works and what it can bring to research—and also how researchers have dealt with its limitations and possibilities—is discussed in the next section, in which we introduce reconstruction as a method, describing its typologies and the evolution of its use as a research method in art historical painting investigations.

On Reconstruction as a Method: Typologies and Evolutions

For the purposes of this essay, we divide painting reconstructions into illusionistic reconstructions and non-illusionistic reconstructions. Illusionistic reconstructions, as the name indicates, replicate the appearance and/ or form of the original object. Meanwhile, non-illusionistic reconstructions do not attempt to reproduce the image itself but instead recreate another aspect, often related to the materials the artists used, and typically examine more technical or scientific questions that require close attention to raw materials and their preparation.

Figures 1 and 2 show an example of illusionistic reconstruction, and figures 3 and 4 of a non-illusionistic reconstruction. Hybrid reconstructions that combine elements of both types are also frequently used in art technological studies. For instance, Indra Kneepkens employed both types for her study of binding-medium modifications at the time of Jan van Eyck (before 1390–1441). She calls these smaller reconstructions of specific details “technical tests” and describes how they aid in establishing connections between schematic, non-illusionistic reconstructions and the complexities of actual artistic practice emulated in full illusionistic reconstructions. Kneepkens argues that an in-depth understanding of material choices in the artist’s studio can only be reached when materials are tested in their full context, combining all the three categories (non-illusionistic and illusionistic reconstructions as well as “technical tests”) and taking into account the tools used for their application.5

In the early 2000s, Leslie Carlyle introduced the concept of “historical accuracy” to the research field and initiated a four-year research initiative called the HART Project, (Historically Accurate Reconstruction Techniques). She started from the premise that it is impossible to mimic historical artistic effects with the highly refined, processed materials currently available in art supply stores and chemical laboratories. Based on her experience, she argued that these materials differ too much from those available in former centuries to be representative.6 Her approach, which aims to increase the accuracy of reconstructions, has had a significant impact on reconstruction-based studies within technical art history, can be summarized as follows. Reconstructions of historical materials or techniques must be based on a broad collection—and in-depth investigation—of recipes in historical sources. In reconstruction design, the researcher should source materials that are as similar as possible to those available in the period under investigation, and they should take field notes during their execution of the reconstruction. Researchers should also consistently analyze their reconstructions, both visually and through instrumental investigation, and compare them with the actual object or work that motivated the research question.7 In response to concerns about the term “accurate,”8 Carlyle expressed her agreement that 100 percent accuracy is not achievable, as no one can ever be fully certain of the exact nature of materials and techniques used by one artist on one day in one place. Assumptions and compromises are unavoidable, and researchers need to consider these, along with possible personal biases, in the assessment of reconstruction outcomes. Carlyle clarified that the aim of accuracy is key, and at the same time she suggested the term “historically appropriate” as an alternative to the unattainable goal of complete historical accuracy.9

Reconstructions, as described above, belong to a larger category of research methods that redo or remake the object of their inquiry. This larger category includes digital reconstructions that simulate a supposed prior stage of a painting, building, or object—possibly an impression of what an object looked like before time took its effect10—sometimes including digital layers projected onto an object as an alternative to a more invasive and irreversible restoration treatment.11 Sven Dupré and his coauthors highlight that reconstructions play roles in many fields of the humanities and discuss the various terms that these different fields use to describe the process of redoing or recreating, from archeological reconstructions of ancient sites, to historically informed musical performances with period instruments, to the reenactment of historical walks. Their volume also provides an entry into the various applications of reconstructions as a teaching tool, in educational institutions and museum settings alike, and in research—the main topic of this essay.12

Two main issues are intrinsically linked with reconstruction as a research method. The first is the distance in time, place, and knowledge between the researcher and the original creator or creators, in our case the maker of the painting. As discussed above, one can never know all details of historical production and cannot ask a seventeenth-century artist to explain their motives. Therefore reconstructions always contain a creative element, which must be acknowledged in the conclusions that are drawn. After performing a reconstruction, a researcher may be able to draw conclusions regarding the feasibility of a method and describe its general effect, but the researcher cannot be fully certain that an artist would have explained his method with the same argument.

The second issue linked to reconstruction is the influence of the position and background of the reconstructing researcher. Reconstructing involves immersion in experimentation that asks for creativity on the part of the researcher; it is a non-neutral process of reenactment that is codetermined by the context and experience of the researcher.13 The professional and cultural stance of a seventeenth-century artist would have been completely different than that of the present-day reconstructing researcher. This is unavoidable, not least because the essential aim of the recreator is different from that of the creator. A recreator reconstructs in order to understand an earlier process, while the painter is focused on developing or creating a work of art. Yet, as the cases discussed below demonstrate, carefully interpreted reconstructions can help establish a link between visual observation, scientific data, and the process of which the painting is a result, using the researcher’s own sensory experience.

The reconstructions of Ryckhals’s painting were made by Lieve d’Hont, in collaboration with and supervised by Maartje Stols-Witlox. Research and reconstructions for the gray-over-red ground were headed by Maartje Stols-Witlox, partly in the context of master’s thesis research by University of Amsterdam student Laura Levine, supervised by Maartje.14

Recreating Visual Effects on a Black Ground: Illusionistic Reconstruction of Ryckhals’s Boy Sleeping in a Barn

We know relatively little about François Ryckhals (1609–1647) and even less about his materials and techniques, due to a lack of technical analysis of his paintings. Ryckhals worked most of his career in Middelburg, the capital of Zeeland and an important trade center.15 Ryckhals was also active in Dordrecht for a few years and had ties to Antwerp through his grandfather, who left Antwerp for Middelburg in 1589, probably to find a safe Protestant haven after Antwerp was reconquered by Spain.16 David Teniers II (1610–1690), active in Antwerp, collaborated with Ryckhals on a few paintings.17

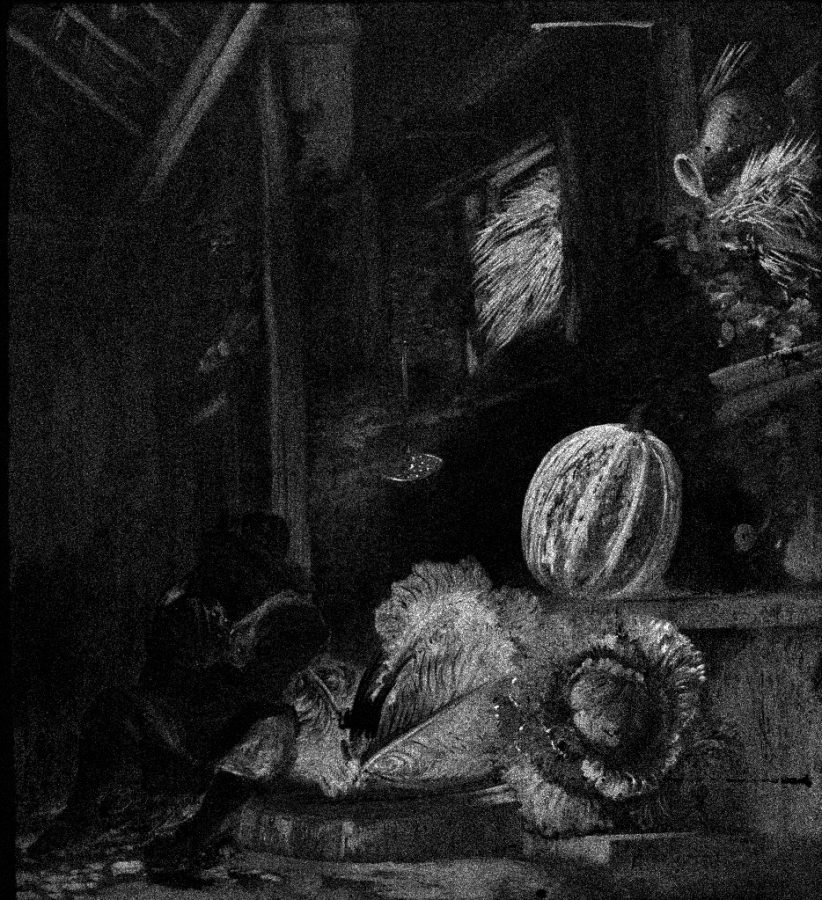

Ryckhals mainly painted subjects related to farm life—livestock in barns and interiors scattered with earthenware and vegetables—with limited attention to human activity. The buildings he rendered were often not clearly outlined or composed. His skill in convincingly depicting the materiality of pots, pans, and vegetables, however, is clearly visible in his pronkstillevens (roughly, “ostentatious still lifes”), in which there seems to have been considerable influence from Jan Davidsz. de Heem (ca. 1606–1685).18 An exhibition dedicated to Ryckhals in Zierikzee in 2019–2020 provided the opportunity to see eighteen of his paintings and two drawings together in one place.19 Below the freely and openly applied paint layers, different grounds were visible to the naked eye, their colors ranging from light yellow-brown and warm midtone browns to black grounds that add dramatic light effects to some of the paintings.

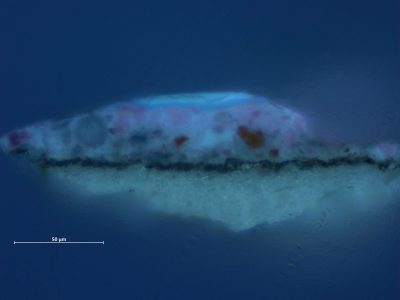

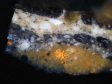

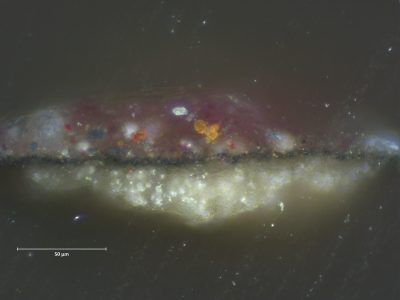

Like the majority of Ryckhals’s works, Boy Sleeping in a Barn is a relatively small panel, made from a single board of vertical-grained oak (fig. 5). The very thin, black second ground layer is a striking and rare feature of this painting. It is applied over a chalk-based first ground layer. As discussed by Marya Albrecht and Sabrina Meloni in this issue, Dutch seventeenth-century painters rarely employed dark grounds.20 Black grounds are even more exceptional, and this painting offers a rare opportunity to gain insight into the way they were used.21 In Ryckhals’s painting, the black ground layer is very thin (about five microns in cross-section; figs. 6 and 7) with local variations in thickness. It is a warmish black that consists of lamp black with tiny quantities of vermilion,22 silicates, a copper-containing blue (verditer or fine azurite), yellow earth, and red lake on an alum substrate.23 The elaborate mixture of pigments could be an indication that Ryckhals mixed palette scrapings into a black paint.24 Using stereomicroscopy, we observed that the dark layer consists of a pattern of tightly packed, small droplets (0.5–0.9 millimeters in diameter). Each droplet is thin in the middle, where more of the white chalk ground shimmers through, and thicker on the edges. Because of the variations in darkness that this phenomenon creates, the ground has a vibrance and texture that plays a distinctive role in, for example, the big red cabbage, where it adds a depth of tone to the core of the vegetable (fig. 8). The drop-like effect suggests a distinctive application procedure, possibly involving specific tools or unusual binders. The dark color of the ground contributes to the appearance of the painting in several ways. When covered only with a very thin layer of light paint, the ground shows through to some extent, providing midtones through the optical mixing of these two layers (fig. 9).25 In other areas, it is left fully exposed. There, the ground functions as the darkest tone, creating shadows next to lighter paint strokes. Further, the ground plays a role below translucent glazes as a dark undertone that helps to create rich and deep colors (fig. 10).

The general working order of this painting appears to have been from back to front, with Ryckhals adding increasing amounts of light paint as he progressed toward the areas in the foreground. In the background, Ryckhals used paints of varying thickness and allowed the ground to remain visible to a greater or lesser extent. The Mauritshuis researchers established that the palette includes natural earth pigments; opaque synthetic, inorganic pigments such as lead white and vermilion; and organic translucent red and possibly yellow lake pigments. The paint layers have mostly been applied alla prima (wet-in-wet), with few local underpaints for specific visual effects. The painting appears to have been made in a short time span, and the many wet-in-wet areas, where different colors blend together, make it hard to grasp the exact order of painting. It is clear that Ryckhals painted the boy as part of a final stage, on top of the finished interior. Available instrumental analyses did not provide information on which binding media were used. For the paint layers, oil is assumed, but the medium used for the dark ground remains a mystery. This leaves open the question of how the droplet pattern was created.

While Ryckhals’s palette is comparable to that of other genre and still life painters,26 his technique is special. How did he manage—or even exploit—the near-black ground, and what might the reasons have been for his choice? Reconstructions can help us understand its implications. As will become clear, they provide insights into Ryckhals’s choice of certain pigment mixtures and how these choices relate to the near-black ground.

During her reconstruction of Ryckhals’s painting, Lieve d’Hont paid special attention to the optical effects and handling properties of materials in her field notes (fig. 11). In view of our question about the relationship between pigment use and a black ground, we opted for a combination of schematic hybrid reconstructions and a full-scale illusionistic reconstruction.27 This combined approach acted as a framework in which we could move back and forth between smaller experiments—to test one or two pigmentation variables at the same time, or to explore options for the patterned ground—and the full-scale illusionistic reconstruction, in which we examined the artist’s choices, testing hypotheses about the ways he used his materials.

Lieve used materials that resemble Ryckhals’s as closely as possible.28 Compromises were unavoidable in the use of modern brushes, as it was not feasible to make brushes like those that were available to Ryckhals, given the level of skill it requires. Knowing that flat brushes were introduced only later, we prioritized round brushes.29 The width of the brushes was based on the width of the marks left in the paint by Ryckhals. The brush hairs were of period-appropriate natural materials (bristle hogshair and smoother sable), and Lieve switched between both based on her prior reconstruction experience. Applying the paint with the brush type that seemed most suitable to her, Lieve found that this approach influenced the resemblance between her own paint strokes and those of Ryckhal much more than the brush material itself.

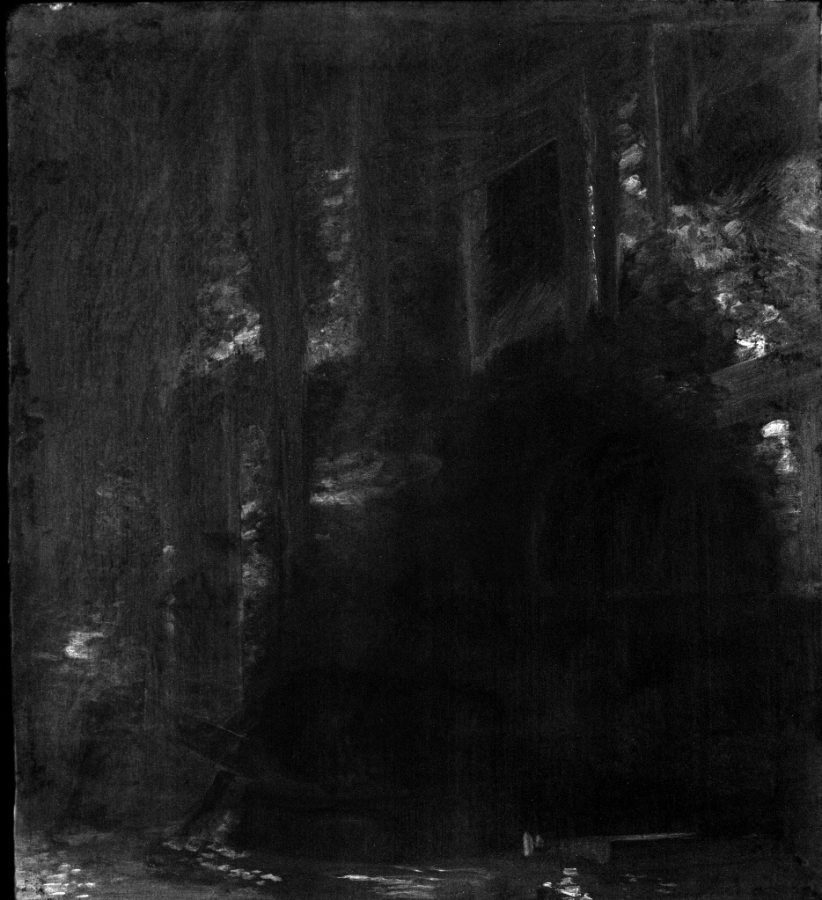

Through reconstruction, Lieve noticed that the basic tonal range of the painting on a black ground needed to be established early on in the process, as all paints applied to a black surface appear lighter and in strong contrast to it. She also had to adjust her chromatic expectations of how colors would appear, because they do not look the same on a black ground as they do on differently colored ones; she ended up using a black tile as a palette for color mixing (fig. 12).30 The need to establish the tonal range is a plausible explanation for why Ryckhals started his painting with the cool orange midtone brushstrokes of the architectural elements, such as the wall beams and the window frame.31 This first phase was executed almost in monochrome, with paint containing lead white, yellow ocher, vermilion, and lead-tin yellow. Lieve applied this layer with a sable brush in different thicknesses, leaving the black ground partly visible through the thinner areas of paint, as Ryckhals had done. Like the sketches in brown and/ or gray paints commonly used on colored grounds in seventeenth-century paintings,32 this phase served to set the scene and give an initial illusion of space. After this first sketch, Ryckhals built up the painting by working toward the darker, receding background and the lighter wall in the middle plane (fig. 13). The vegetables were left in reserve and executed later, with more elaborate layering. The fact that Ryckhals made few adjustments in this painting seems to indicate that Boy Sleeping in a Barn was not his first painting on such a dark ground.

The MA-XRF mappings of the painting revealed an unexpected distribution of tin and mercury (figs. 14 and 15).33 These chemical elements, which appear as the lighter portions in each image, are markers for the bright yellow pigment lead-tin yellow (a lead-tin oxide) and the vibrant red pigment vermilion (mercury sulfide), but they are also detected in areas that are neither distinctly yellow or red. Furthermore, the amounts added are so small that these pigments would not modify their color. The fact that the signals for tin and mercury echo the composition of the painting means that they are present within the paint layers. The reasons for their presence throughout the background, neither distinctly red nor distinctly yellow, and even appearing in more shadowy areas, are unclear.

When during the reconstruction Lieve added small amounts of lead-tin yellow or vermilion to her paints, she saw an effect that helps us understand why these elements were found throughout the MA-XRF scans. Even in small amounts, lead-tin yellow influences the opacity of the paint, which allowed her cover the ground in selected areas so well that tonal variation could be created in the more subdued tones in the background. This was the first hint that Ryckhals thought beyond the color of a pigment and purposefully played with transparency or opacity, seeking to balance the visibility—or invisibility—of lower layers throughout the painting process. Only then did we start to notice more modifications of paint transparency with small amounts of either very opaque or very transparent pigments. Pigments like lead-tin yellow or vermilion were not necessarily added for color, we realized, but to change the visibility of the ground and lower layers. The reverse is also true; considerable amounts of calcium were detected in areas such as the wooden beam behind the boy, the light-yellow of the cabbage, and the purple of the red cabbage. The presence of this calcium might either be explained by the use of now-discolored, calcium-containing lake pigments, or they could be admixtures of calcium carbonate to the paint. Because chalk is relatively transparent in oil, both when mixed in by itself or when used as a basis for a lake, each of these options would increase the visibility of the dark ground through the paint layer: the lake would add a reddish color, while a calcium carbonate addition would not have a strong influence on the colors of the surface paint (see fig. 12).34

Efficient use of pigment opacity in mixtures or layering of pigments allowed Ryckhals to create many visual effects with only a limited number of pigments, contributing to the liveliness of the finished painting (fig. 16). Bright opaque pigments contribute to what art historian Paul Taylor called “chiaroscuro of hue.” Such opaque pigments are brought forward because of their chroma, their strong brightness, as can be observed in figure 12, where the bright red vermilion seems to be nearer to the viewer than the darker red lake, which optically recedes in space. Combining well-placed bright whites, yellows, oranges, and pinks, which visually move forward, with darker and more deeply colored pigments, which visually move backward, can support the illusion of three-dimensional space.35 It cannot have been a simple process for painters to consider color, transparency, tinting power, and saturation all at the same time. In addition, they had to think about various paint viscosities and the effects certain pigments have on the paints’ drying time. In short, they needed to know their materials inside out.

As the reconstruction grew under Lieve’s hands, she could trace how, throughout the buildup of his painting, Ryckhals enhanced the extremes of the color values (the light-dark contrast) with lighter opaque and darker transparent pigment mixtures, demonstrating an intimate, instinctive knowledge of the opacity of the pigments he used. The inquiring stance adopted during reconstruction thus helps unravel and make explicit the hidden dimensions of artistic practice. Retracing Ryckhals’s steps has given us a better understanding of phenomena observed in the original painting and helped us formulate an alternative hypothesis to explain the presence of certain pigments in the color mixtures. We now better understand the role of the ground throughout Ryckhals’s painting process. Starting from this dark ground, purposefully adjusting the transparency of colors placed on top with small additions of opaque or transparent pigments, and selecting pigments that optically come forward or recede, Ryckhals was able to create an appealing painting that at the same time convincingly captures the darkness of the interior of a barn and the lively and vibrant colors that result from direct light coming in from the left.

Non-Illusionistic Reconstructions of Double Grounds on Canvas: Gray-Over-Red Grounds

As discussed in the introduction to this special issue, many artists used the tonality of colored grounds in their final image.36 For instance, Petria Noble’s article in this issue discusses Rembrandt’s frequent use of gray or brownish grounds, which often remain in view around the eyes of his sitters and in transitions to shadowed areas.37 In his Self-Portrait of 1659 (fig. 17), the gray ground can be seen in many areas. Rembrandt executed this painting on a ground consisting of a lower reddish layer covered by a gray second ground containing lead white, bone black, and umber.38 He started the painting with a brown sketch. As this sketch has worn a little with time, the gray ground may now be slightly more visible than when the painting was fresh.39

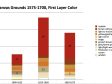

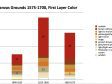

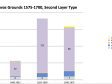

Recently, more in-depth investigation into the typology of double gray-over-red grounds has become possible thanks to the work of Moorea Hall-Aquitania (reported elsewhere in this special issue).40 The database that Hall-Aquitania developed for the Down to the Ground project (see this issue’s introduction) contains data on the ground color and composition of more than eight hundred Flemish and Dutch paintings dating between 1500 and 1650, and thus provides important insights into the frequency and typology of lead white over yellow/ red double grounds in Dutch seventeenth-century paintings.41 Figures 18, 19, 20 and 21 illustrate the wide dissemination of gray-over-red double grounds and give an overview of variations in their pigmentation and the thickness of their layers. The use of this type of ground included France, where it remained highly popular until well into the eighteenth century.42 In her essay in this issue, Anne Haack-Christensen illustrates the use of this same type of ground by the artist Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts while he was working in Denmark.43 In the Netherlands, the type was used by—among others—Antwerp painters like Daniël Seghers, by the Utrecht Caravaggisti, and in seventeenth-century Amsterdam by Rembrandt and his contemporaries.

Figures 22, 23, 24, and 25 extract the double grounds of Dutch and Flemish canvas paintings from the Down to the Ground database and explore the general composition and tonality of their first and second layers.44 As discussed in this issue by Hall-Aquitania and Van Laar, colors have been simplified to allow for their grouping.45 Local preferences are not specified; neither are overrepresentations of certain artists whose works have received unequal attention. Only by going through the source data can we see that, of the dark brown and reddish grounds, a considerable percentage relates to Utrecht Caravaggisti painters.46

Notwithstanding such caveats, these figures clearly demonstrate that two-layered grounds were in general use during the period and highlight the frequency of gray-over-red grounds. While no recipe from the period studied explains the choice for double instead of single grounds, a 1766 French source explains that multiple ground layers more successfully even out the canvas weave, thus providing artists with a smooth picture plane.47

The fact that seventeenth-century artists like Rembrandt exploited the ground’s color in their final images has drawn attention to the question why his contemporaries were also so fond of the gray-over-red ground. Why would artists choose a strongly colored first layer and then cover it up with a second layer? Was it about the color or about something else? Two theories have been put forward to explain artists’ motives for working on a gray-over-red ground, one highlighting economic benefits of using ochers when possible and the other proposing a visual effect of this layer structure. In Rembrandt: The Painter at Work, Ernst van de Wetering points out the price difference between cheaper earth pigments, typical in the lower layers such as grounds, and the more expensive lead white on which the gray layer is based. Van de Wetering supported his argument that artists chose this type of ground to save money by referring to a comment from Theodore de Mayerne’s Pictoria, Scultoria et Quae Subalternarum Artium (ca. 1620–1644). In a recipe for a two-layered ground, Mayerne notes: “If one wishes to save one could make the first layer of ocher before applying a lead white based ground layer.”48

Rembrandt researcher Karin Groen introduced a second theory for the popularity of gray-over-red grounds. She hypothesizes that the red ground influences the tonality of the gray top layer, rendering it a warmer gray that would have been more pleasant for painters to work on.49 Groen cites an eighteenth-century recipe for a double ground with a warm reddish-gray top layer in the anonymous Nieuwen Verlichter (1777). The recipe prescribes: “Lead white mixed with brown red and a little coal black, to give the ground a reddish gray, which generally matches with all colors in painting.”50 While it could be argued that this recipe is not very strong support for Groen’s theory, as it recommended adding brown-red pigment to the gray layer—rendering the layer itself a warmer gray—Groen’s theory may still be true. In any case, the two theories are not mutually exclusive.

Whatever the reasons artists chose a gray-over-red ground, its deliberate visibility in finished seventeenth-century paintings motivates the question of whether the gray we now see still meets the artists’ original intentions. This question comes up because one of the main pigments in the second layer, lead white, is known to become more transparent over time due to lead saponification, a chemical reaction with the fatty acids in the oil binder. Lead saponification always occurs in oil paints and is one of its main drying mechanisms. When oil paint dries, lead becomes part of its network—a chemical lattice of dried and polymerized oil paint. Lead compounds speed up the drying of oil paints and contribute to the strength of the paint, but unfortunately, saponification can also lead to less desirable effects. It continues throughout the life of a painting, and over time, when too many lead white particles disappear, too few may remain to retain the original opacity of the lead white–containing gray ground layer. A layer may then become more transparent than the painter intended it to be.51 When such reactions change the opacity of the gray part of the gray-over-red ground, the underlying red layer can become more visible, changing the tonality of the ground. We may thus wonder whether the gray that we observe around the eyes of Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait (see fig. 17) still matches the painterly qualities the artist wanted to convey.

We used reconstructions to test basic assumptions behind the theories described above. Exploring such matters requires rigorous attention to materials, which need to resemble the originals, and methods, as the reconstructions must be designed in such a way that specific effects can be investigated in isolation. This calls for reconstructions with stepped proportions, in which the researcher changes only one variable at a time; in this scenario, the ultimate replication of the painted image is less relevant. Therefore, in this case the reconstructions do not include details of the composition, as was the case for the Ryckhals reconstruction. Instead, they are simple, monochromatic, superimposed layers of an even thickness. Without the aesthetically pleasing but eye-distracting details of an illusionistic composition, such reconstructions allow for the clean comparison that is needed to answer the question whether the red layer shines through. We made our reconstructions based on the general typology of this type of ground system, and the techniques employed in their creation were based as much as possible on historical recipes, combined with results from scientific analysis of the materials used in seventeenth-century paintings.

The red layer in gray-over-red grounds typically consists of different mixtures of earth pigments, with various percentages of clays, and/ or chalk. The second layer always contains lead white and is toned gray or brownish gray, with additions of blacks, earth pigments, and/ or some red. We will refer to this type of ground as gray-over-red in what follows, while keeping in mind that the red layer in this case covers a broader range of pigments and fillers, including chalk and clay minerals, and that the gray of the second layer may range from pure gray to brown tones.

Historical recipes echo the trends observed in these paintings and provide supplemental information on the choices of ingredients as well as application methods (Tables 1 and 2). Of the twenty-seven seventeenth-century canvas ground recipes from the Netherlands, England, and France described in Maartje Stols-Witlox’s book A Perfect Ground, nine are for double grounds with a lower layer of yellow or red earth pigments and a top layer based on lead white toned with various pigments (typically grays or browns, tinted with black pigments and/or umber).52 Interestingly, Italian and Spanish recipes from 1550 to 1700 give a completely different picture (Table 2). Here, very few recipes fit the lead white-over-earth type. Instead, single grounds are dominant—sixteen of a total twenty recipes discussed.53 With the exception of a recipe in Vasari (1568 edition), all Southern European recipes for double grounds occur in a single seventeenth-century Spanish source (Pacheco, 1649).54 Given the small number of available written records, a definite conclusion would seem presumptuous. However, recipes do seem to suggest that red-over-gray grounds are mostly a northwestern European phenomenon.55

Having discussed the general typology and occurrence of gray-over-red grounds, we now turn to the reconstructions themselves, starting with those that examine the plausibility of the hypotheses put forward by Van de Wetering and Groen, followed by reconstructions that examine the potential effect of the gray top layer’s increased transparency on the visibility of the lower red ground layer.

To explore the hypotheses of Van de Wetering and Groen, we made reconstructions with gray top grounds of different thicknesses and weighed the amount of material used to calculate the financial benefit of using a gray-over-red ground on a larger canvas. For these reconstructions we prepared a generic gray-over-red ground that mimicked the type found in painting examinations, following historical recipes (see Table 1, recipes marked blue) and combining details from individual recipes in order to arrive at as complete a procedural description as possible. Table 1 shows that following recipes means interpreting instructions that can be rather vague; proportions are rarely given, and pigment names may have changed. One also has to choose between the different materials mentioned.

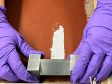

Maartje began by stretching three plain-weave linen canvases on a strainer and applying a sizing layer of warm hare glue in distilled water (10 grams in 90 milliliters); the percentage is based on prior recipe-based reconstructions into animal glues and their properties.56 When the canvases were dry, Maartje rubbed their surfaces smooth with a pumice stone until the knots and loose threads had been removed, as advised in a number of recipes. For the red of the first ground layer, we had to choose between ocher and bole, both regularly mentioned in the historical recipes. Both are earth pigments with various proportions of clay minerals, but bole pigments have a specific particle size (platelets) that makes them very suitable as a preparation layer for gilding. As gilding was not included, and as ochers have a particle shape that is more common in artist pigments, Maartje decided on red ocher. We did not have a reddish shade available that visually matched the shades observed in historical paintings, so Maartje followed instructions in a recipe from the Mayerne manuscript to burn yellow ocher on a stove until it turned red. This red ocher was subsequently ground in linseed oil with a glass muller on a glass slab, and we collaborated in spreading it out on the canvas with spatulas as regularly as we could, just thick enough to fill the interstices of the weave and cover the high points, thus evening out the irregularities of the weave (figs. 26 and 27). The red ground was dry to the touch in two weeks but was left to further age and harden for ten months before it was lightly pumiced and the second gray ground was applied.57 For the gray layer, we used lead white prepared according to seventeenth-century procedures mixed with carbon black.58 All paints were made by hand, grinding the pigments on a porphyry slab with a muller and using cold-pressed linseed oil—chosen because it is a common binder, and because no specific additional oil-processing treatments are described in the recipes.59

The main object of the query related to Groen’s theory was the opacity of the second ground. Because opacity depends on layer thickness, and different layer thicknesses are encountered when examining seventeenth-century Netherlandish paintings, different thicknesses were tested that represent the range observed in painting examinations. To ensure an even and measurable thickness of the second ground layer, it was not applied with a spatula, as a painter would do, but instead with a drawdown bar, a type of bar with feet of a precise height on either side (fig. 28). Drawing the bar over the paint, Maartje spread very even layers of thirty, sixty, and ninety micron thicknesses.

The reconstructions led to unexpected conclusions. To our surprise, even a very thinly applied gray layer based on lead white fully blocks out the first red layer. Neither the human eye nor instrumental analysis with a spectrophotometer detected any red penetrating through the gray layer of 30 microns (fig. 29). Only when Maartje scraped this layer all the way down to the red layer with a spatula did the red ground started to play a visual role. It had an uneven, patchy visibility, caused by irregularities in this first red layer (fig. 30).

To test Van de Wetering’s hypothesis of a financial motive for the red first ground, we needed to compare the pigment costs of an ocher-based layer with those of a lead white–based layer. For each square centimeter of red ocher ground, Maartje needed 0.035 grams of pigment. For each square centimeter of a gray lead white ground of sixty-micron thickness, more weight was needed: 0.050 grams of lead white. The weight difference is logical, as lead white is much heavier than red ocher. Van de Wetering provides ocher and lead white prices from a 1658 Rotterdam archive and a 1667 Dordrecht price list: yellow ocher is five guilders per one hundred pounds, while lead white costs 14.75 guilders per one hundred pounds.60 Taking these prices as a basis, the pigment prices per gram are respectively 0.002 stuivers (ocher) and 0.005 stuivers (lead white).61 For a painting of moderate size, like Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait (see fig. 17), which has a surface area of 5,577 centimeters square, an ocher layer would take 195 grams and thus cost 0.39 stuivers, while a lead white layer would take 279 grams and cost 1.39 stuivers. A lead white–based layer thus costs about 3.5 times as much as an ocher layer. Naturally the exact costs will have varied depending on size, the thickness of the layers, and prices, which would have fluctuated with time and location, but this calculation does confirm Van de Wetering’s theory of a measurable price difference. For a smaller painting the size of Rembrandt’s portrait, this may not have mattered much, but for a professional primer or a painter working on large formats, it may indeed have been attractive to consider using cheaper earth pigments instead of more expensive lead white in a first ground layer. Of course, the price of the materials used to prepare canvases is only one factor in the total production costs, but it may still have been relevant. Whether the earth pigment used was red, light brown, or yellow may not have a main selection criterium and may relate mainly to local availability or local habit.

To test a possible effect of saponification that may occur during the aging of a lead white–containing layer, we also applied more transparent gray layers on top of the first red layer. We made these layers more transparent by replacing some of the opaque lead white pigment with fillers that are transparent in oil binders: colorless glass and chalk.62 Throughout the reconstructions, executed by Laura Levine and Maartje Stols-Witlox, the volume ratio of black pigment remained constant in relation to the volume of the other pigments (lead white alone, or lead white with colorless filler).63 This was important because in order to compare the effects of replacing lead white with more translucent materials, the lead white replacement should be the only variable, with the proportion of other ingredients remaining constant. Laura also tested the effect of adding more oil to the lead white–based layer—a test in which the proportion of ingredients was different. This test did not lead to a feasible two-layer ground, as adding oil increased the fluidity of the gray paint to such a degree that it was no longer possible to apply a layer of the thickness observed in historical painting grounds. It instead flowed out into a very thin layer.

Our attempts to mimic with glass or chalk the effect of increased transparency due to saponification of lead white in the second ground layer demonstrated that even when half of the lead white (in weight) was replaced by transparent material, and applied very thinly in a thirty-micron layer, the gray retained its opacity.64 However, replacing part of the lead white with chalk or glass did have one other effect: it significantly darkened the tonality of the gray (figs. 31, 32 and 33). The impact of a darkening gray ground would have varied over time, but these reconstructions demonstrate that it could affect paintings with such a layer build-up. It could then change the artist-intended effect of this gray ground. Impact could be local, if a painter only made local use of the ground color, but in cases where an artist used the ground color for the overall tonality, increased transparency due to saponification may result in generally darkened tonality. Whether such a degradation through time has indeed has affected a painting can be investigated by analyzing the degree of saponification of the ground and by checking for the presence of smaller lead white particles using microscopy.

From these reconstructions two main conclusions can be drawn. First, Van de Wetering’s hypothesis of an economical motive for gray-over-red grounds seems much more likely than Groen’s theory that the red first ground warms the tonality of the gray ground applied on top. Tests examining the second question of whether saponification of the lead white could increase the visibility of the first red ground, demonstrated that even when a substantial part of lead white reacts away with age, a reddening of the gray ground does not seem to happen easily. Lead white is simply too opaque for the color of the lower layer to play a significant role, even when quite a large proportion of it is replaced with a more transparent material. However, while a warmer gray than intended by the artist seems unlikely, the reconstructions did alert us to a degradation effect previously not associated with this type of ground, namely darkening due to lead saponification. The overall effect of such darkening is difficult to predict, because the other layers of paintings also change with time. Lead white was used in all layers of seventeenth-century paintings. Therefore, lead saponification occurs throughout the paint layers.65 Changing ground tonalities therefore need to be considered in the context of an entire painting that also changes; the total factors and effects are more complex than a study into just the ground can cover.

Reconstructions in Art Historical Studies

The two different cases discussed above exemplify different applications that reconstructions may have for art historical research. They also demonstrate how reconstructions are both based on and support other research methods employed to study making processes.66 The case of Ryckhals exemplifies how reconstructions can be used as a framework to connect social histories of making with elements linked to formal analysis. The second case of the gray-over-red grounds is primarily concerned with the connection between the original work’s economical and practical contexts and its present-day visual qualities. Through the sensory activity of reconstructing, we studied paintings as process, building them up from scratch and going through the motions and stages the original painter would have experienced. Our personal observations led to surprising insights: for instance, the new hypothesis explaining that Ryckhals added tiny amounts of opaque yellows and reds to many of his colors to influence their opacity. The fact that reconstructions are three-dimensional visual aids adds to their value. They can be used to demonstrate and to educate, as testified in the illustrations that accompany this essay.

As with all reconstruction-based studies, the person of the researcher is both an important asset and a limitation because our skills, knowledge, and context differ from those of the original artist. After all, “we” were the ones who experienced certain effects and learned by doing, in our own context in the conservation laboratory, with different experiences and purposes than the original artists. While we know that we will never fully understand the artists, these cases demonstrate that our doing sensitized us, as researchers, to aspects of making that would otherwise have remained overlooked.

Reconstruction is a creative process that requires that decisions be made even when there are gaps in our knowledge of the exact historical process we reconstruct, and also when compromises are unavoidable. For physical making processes, one cannot skip a step; something needs to be “there” before the next material can be added or the next layer applied. This is a fundamental difference between a reconstruction and a writing process, in which the author may conclude that something remains a question and nevertheless continue on to discuss the next phase. We consider it an asset that physical reconstructions thus force a decision—they impel us forward. But at the same time it is a limitation, as a perfect replica is not achievable. Differences should be described, for example, concerning the tools employed (modern brushes, a drawdown bar), and their impact on the conclusions that can be drawn must be acknowledged. In our case, we have refrained from definitive statements about historical practice, focusing instead on practical likelihood, observed effects, and material affordances, tentatively connecting these aspects to the paintings studied.

In the cases we discussed, results from instrumental analysis, visual observation, and historical research not only stood at the basis of our reconstructions, but these results were also connected through their application. In this essay, the questions we address concern specifically the motives for using colored grounds and how their use connected to other steps in the painting process. We hope that these cases were sufficiently varied to spark ideas for new reconstruction projects to support art historians, conservators, and conservation scientists in their research practices. When used with care and integrated with other methods, reconstructions offer a framework that allows us to achieve deeper and broader art historical insights.

Tables

Table 1 - North European Canvas Ground Layer Recipes 1550–1700 (England, Netherlands, France)

Double grounds consisting of a lower layer of ochers or other earths/clays covered with a lead white–based second ground are marked in blue; recipes marked in gray have a first layer based on chalk, covered with a second lead white–based layer.1 Between parentheses is the number of applications per layer, if specified in the recipe.| Source | Country of writing / publishing | Size Layer | Smoothing | First ground | Smoothing / Isolating | Second ground | Smoothing | Third ground |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paris,2 BnF Ms. Fr 640, ca. 1580–1600, fol. 57r | FR | Common ashes, oil, chalk, or colors gathered from the vessel where one cleans the paint brushes | ||||||

| London, MS Sloane 1990, ca. 1623–1644, fols. 78–79 | UK | Size | White chalk, glue, honey (×1) | Ocher, oil, a little minium to speed up drying (×1) | Burnt sheep’s bones, a little lead white to give body, massicot to speed up drying (×2) | |||

| London, MS Sloane 1990, ca. 1623–1644, fols. 78–79 | UK | Size | White ground with glue, a little honey (×1–2, with brush) | [Lead] white, a little minium | ||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 11 | UK | Calfskin glue or cheurotin | While size is wet, flatten with muller on marble | Lead white, umber (×1–2) | ||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 98v | UK | Bathe in liquid glue, size with liquid glue, or apply gelled glue from glove leather clippings (bone or spatula) | Cut the knots in the canvas with a well cutting [sharp] iron, pumice stone | Lead white, a little ocher, minium or other competent color (with spatula) | ||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 98v | UK | Bathe in liquid glue, size with liquid glue, or apply gelled glue from glove leather clippings (bone or spatula) | Cut the knots in the canvas with a well cutting iron, pumice stone | Lead white, carbon black (with spatula) | ||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 5 | UK | Glue of clippings of leather or glue that is not too thick (×1) | Brown-red or brown-red from England (x1) | Flatten with a pumice stone | Lead white, carbon black, small [smalt] coals, a little umber (×1 or 2) | |||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 5 | UK | Glue of clippings of leather or glue that is not too thick (×1) | Ocher burnt that reddens in the fire (×1) | Flatten with a pumice stone | Lead white, carbon black, small [smalt] coals, a little umber (×1–2) | |||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 87 | UK | Strong glue or leather clippings glue, not too strong (×1 with knife) | Bole, umber, oil (×1 with brossette [brush] or knife) | Remove all knots by scraping with a knife and flatten with a pumice stone | Lead white, umber | |||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 90 | UK | Strong glue (×1 with brush, then knife) [Mayerne notes that this formulation tends to crack] | Bole, umber (×1) | Lead white, umber (×1) | ||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 95 | UK | Bole, umber (×2–3) | Smalt, lead white, a little lake | |||||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 96 | UK | Strong glue | Bole, umber | Lead white, a little umber | Rub with pumice stone to remove knots | lead white, a little umber, smalt, polish with brush | ||

| Mayerne, 1620–1644, fol. 98v | UK | Bathe in liquid glove clippings glue, cover large canvas with gelled glove clippings glue (spatula) or with warm glue | Cut the knots of the canvas with a sharp knife, pumice stone | Yellow ocher (×1 with spatula) | Lead white, a little ocher, minium, or other competent color; or lead white, carbon black (×1) | |||

| Lebrun, 1635 (Merrifield 1849), 820 | FR | Parchment glue and oil priming (×1) | ||||||

| Lebrun, 1635 (Merrifield, 1849; 1849), 772 | FR | Parchment or flour glue (with knife or spatula) | Potter’s earth, yellow earth, or ocher ground with nut or linseed oil (with knife or spatula) | |||||

| Recepten-boeck, ca. 1650–1700, fol. 5 | NL | Glue, red bole (×1) | ||||||

| King, 1653–1657, fol. [48] | UK | Thin starch (with knife) | Pumice | Primer (with wooden knife) | Let dry an hour or two to the end that oyle may sink into cloth, with knife stuke [scrape] away all the primer you can. | |||

| Art of Painting in Oyle, 1664, 95–96 | UK | Thin size, honey (×2, first layer warm with brush, second cold with a knife) | Lead white, a little red lead Spanish browne, umber, oyle (×2 with a knife) | |||||

| Salmon, 1672, 141 | UK | Size, whiting ground (×2–3) | Scrape smooth | Lead white, oyl (×1) | ||||

| Félibien, 1676, 407–408 | FR | Glue water (×1) | Pumice stone to remove knots | Brown-red, a little lead white to speed up the drying, nut or linseed oil (× 1 with large knife) | Pass the pumice stone | Lead white, a little carbon black (×1 with large knife) | ||

| Félibien, 1676, 407–408 | FR | Glue water | Pumice stone to remove knots | Brown-red, a little lead white to make it dry sooner, nut or linseed oil (with large knife) | Pass a pumice stone | |||

| De la Fontaine, 1679, 43–44 | FR | Glue | Umber, brown-red (×1 with iron knife) | Rub with pumice stone | Lead white, umber, a little carbon black | |||

| Eikelenberg, 1679–1704, fol. 377 | NL | Porridge of wheat flour (with knife) | Umber, brown-red, [lead] white, a little from the pencil tray or rinsing jar (x 1 or 2) | Knife, remove knots and paint skins, using brick or pumice stone | ||||

| Eikelenberg, 1679–1704, fol. 669 | NL | Porridge of wheat flour (applied with brush, smoothed with palette knife) | Knots and dirt removed with a leksteen [polishing stone] | Potter’s earth, linseed oil | ||||

| Beurs, 1692, 20 | NL | Water and pulp (brij) [probably paste such as that prepared from flour] | Rub on a grinding stone or board | Umber, lead white, oil (×3–4) | ||||

| Dupuy du Grez, 1699, 243–244 | FR | Glue water | Pumice stone to remove knots | Brown-red, lead white, Spanish white, linseed or nut oil (with large knife) | One may pass a pumice stone | |||

| Dupuy du Grez, 1699, 243–244 | FR | Glue water (×1) | Pumice stone to remove knots | Brown-red, Spanish white, linseed or nut oil (×1 with trowel or knife) | One may again pass over the pumice stone | Lead white, carbon black (×1) | ||

1) The information in these tables is extracted from Maartje Stols-Witlox, A Perfect Ground: Preparatory Layers for Oil Paintings 1550–1900 (London: Archetype, 2017), 247–267, appendix 6. Transcripts use original spelling and words, translations are as close as can be understood to the original text. |

||||||||

Table 2 - South European Canvas Ground Layer Recipes 1550–1700 (Italy, Spain)

| Source | Country of Writing / Publishing | Size Layer | Smoothing | First Ground | Smoothing / Isolating | Second Ground |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasari, 1568, fol. 53 | IT | Soft glue (×3–4) | Flour paste with nut oil, lead white (×1 with knife) | Soft size (×1–2) | “The priming” | |

| Vasari, 1568, fol. 52 | IT | Softest glue (×4–5 with sponge) | Nut oil, white, lead-tin yellow, earth that is used for bells (×1 plastered over canvas and beaten with palm of the hand) | |||

| Reglas para pintár, ca. 1575–1600 (Bruquetas–Galán, 1998, 37) | SP | Glue water | Pumice stone | Some oil color (common lead white, minium or black, oil) | Pumice stone | |

| Borghini, 1584 (ed. 1730), 136 | IT | Glue (×1–2) | Colors | |||

| Borghini, 1584 (ed. 1730), 138 | IT | Glue (×1) | Mestica [priming] (×2) | |||

| Borghini, 1584 (ed. 1730), 138 | IT | Volterra gesso, fine flour (fiore di farina), glue and oil (×1 with iron blade) | ||||

| Armenini, 1587, 124–125 | IT | Soft glue (×2–3) | Varnish, white, red | A knife to shave [scrape] gently | ||

| Armenini, 1587, 124–125 | IT | Soft glue (×2–3) | Lead white, lead-tin yellow, earth that is used for bells | A knife to shave [scrape] gently | ||

| Armenini, 1587, 124–125 | IT | Soft glue (×2–3) | Verdigris, lead white, umber | A knife to shave [scrape] gently | ||

| Pacheco, 1649, fols. 383–384 (Véliz, 1986, 68) | SP | Flour or mill dust, oil, a little honey | Pumice stone | Oil priming (×1–2) | ||

| Pacheco, 1649, fols. 384–385 (Véliz, 1986, 68) | SP | Weak size, cold (×1 with knife) | Pumice stone | Linseed oil, Seville clay (×2 with a knife) | Pumice stone after both coats | Oil, Seville clay, a little lead white if you wish (×1 knife) |

| Pacheco, 1649, fols. 383–384 (Véliz, 1986, 68) | SP | Size from glover’s scraps (brush) | Same size, sifted gesso (×2 with a knife) | Pumice stone | Primed (with a brush) | |

| Pacheco, 1649, fols. 383–384 (Véliz, 1986, 68) | SP | Glue size, sifted ashes (with brush and knife) | Pumice stone | Red earth, linseed oil | ||

| Pacheco, 1649, fols. 383–384 (Véliz, 1986, 68) | SP | Size from glover’s scraps (with brush) | Same size, sifted gesso (×2 with a knife) | Lead white, red lead, charcoal black, linseed oil (brush) | ||

| Symonds, ca. 1650–1652, fol. 10 | IT | Layer of glue | Nut oil, lead white, lead-tin yellow, earth that is used for bells | |||

| Symonds, ca. 1650–1652, fol. 10 | IT | Glue of glove cuttings or of glew | Scrape with an iron | Good quantity of oyle (red earth, a little white, chalk, very little carbon black) | ||

| Tractato del arte de la pintura, ca. 1656 (Véliz, 1986, 111) | SP | Flour gacheta [flour paste], a little common oil (with knife) | Loose threads and knots are cut and canvas smoothed with pumice stone | Powdered shells from lakes, linseed oil (as many layers as needed to cover well, with large knife) | Sanded with pumice stone and smoothed and scraped with a sharpened knife | |

| Volpato, ca. 1670 (Merrifield, 1849; (1999), 731) | IT | Glue | Linseed oil, terra da bocali [potter’s earth], red earth, a little umber (×2, second coat more finely ground, applied with knife) | Pumiced | ||

| Hidalgo, 1693 (Véliz, 1986, 137) | SP | Gacha [flour paste], size, honey | Almagra [a red earth] and umber or Fuller’s earth, cooked linseed oil, drier (×2–3) | |||

| Hidalgo, 1693 (Véliz, 1986, 137) | SP | Glove clippings (×2) | Almagra and umber or Fuller’s earth, cooked linseed oil, drier (×2–3) |