The Devote ghetiden vanden leven ende passie Jhesu Christi (Devout Hours on the Life and Passion of Jesus Christ) provides an intriguing case study of text and image relationships in the transitional age between manuscript and print. The 1483 and 1484/5 editions of the Devote ghetiden were an innovative commercial endeavor by the prolific printer Gerard Leeu. These editions of a new vernacular religious text, flexible in use and primarily aimed at laymen, combined with no less than eighty-four full-page illustrations, offered the lay reader an unprecedented level of visual material for private devotion located in the same object as the text. Changes in both composition and page layout, which occurred when text and image were refashioned in a different medium, altered the reader’s meditative experience, reflecting not only the multiform character and individuation of religious practice on the eve of the Reformation but also the influence of printed books on late medieval textual and visual culture as a whole.

In 1484 the Netherlandish printer Gerard Leeu moved his business from the town of Gouda in Holland to Antwerp, where he settled right in the middle of the emerging creative quarter. His printing shop was situated next to Our Lady’s Pandt, the art market where paintings, prints, and books were sold side by side.1 One of the first texts with which Leeu chose to start his business in the developing “capital of capitalism” was a vernacular religious text, the Devote ghetiden vanden leven ende passie Jhesu Christi (Devout Hours on the Life and Passion of Jesus Christ).2 It might well be that the success of the previous (first) edition Leeu had published approximately one year earlier in Gouda influenced his decision. As an entrepreneur Leeu took advantage of the public’s persistent demand for spiritual support and combined it with a clever deployment of his pioneering skills with the latest possibility in book production: the use of woodcuts as illustrations in books printed with movable type. The result was an innovative product targeted particularly at laypeople who felt the pressures of busy urban life and the need for reflection on the state of their souls. The book offered a range of texts, including meditations, the Penitential Psalms, and prayers, accompanied by an extensive program of illustrations. Leeu not only introduced this new compilation of texts and visual material to the market but also devised a novel way of combining text and image in a printed book that fundamentally altered the everyday pious practices of laypeople, thus reflecting changing practices in both book production and lay spirituality. After Leeu’s second edition the Devote ghetiden was reissued at least three times, in Antwerp, Haarlem, and Gouda.3

The decision to publish a second edition of the Devote ghetiden enabled Leeu to reuse the full series of woodcuts he had made for this text. In fact, this is one the first and most influential series of woodcuts with a religious character cut in the Low Countries.4 In 1884 William Martin Conway established that the series as a whole was made for the Devote ghetiden, as this was the only text that fitted all sixty-eight images, some of which were used more than once in the editions. Conway named the artist who cut the blocks for Leeu the “Second Gouda Woodcutter.”5 Leeu and other printers frequently reused these woodcuts, for example, in the extensively illustrated meditative dialogue between Man and Lady Scripture based on the Vita Christi by Ludolf of Saxony (Boeck vanden leven Jhesu Christi) first published in 1487 in Antwerp.6 Although the compositions of the woodblocks have been studied and their possible origin tentatively traced to prints by Israhel van Meckenem and to an older woodcut series from Lübeck made for a vernacular edition of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, the Devote ghetiden itself—the text the images were designed to accompany and which formed the initial context in which the woodcuts functioned—has not to date been the subject of detailed research.7 The importance of the Devote ghetiden for understanding how text-image relationships had an impact on early printed works and late medieval lay spirituality is underlined by the fact that at least two other woodcut series were originally made to accompany editions of this text, though no copies have survived.8 A recent discovery of (parts of) the text in (illuminated) manuscripts suggests an even more prolific circulation of this body of text and images.9

This essay aims to provide a preliminary introduction to the function of the woodcuts within the Devote ghetiden, as spiritual instruments in the religious practice of late medieval readers, pointing to the elements that underpinned both the book’s production and consumption and acknowledging the complex transmission of text and image in the transition from manuscript to print culture. In what follows I will first introduce the contents and structure of the Devote ghetiden and the various functions of the woodcuts. The second section focuses on one specific part of the text—a prayer cycle on the history of salvation—where image and text take on a particularly close association and each opening has the character of an “image-and-text diptych.”10 The third and last section explores the effect of alterations in the composition and execution of the images, and in the layout of the book, on the reader’s meditative experience. Changes occurred when a new series of woodcuts was made to illustrate the text and when both textual and visual material were refashioned from a different medium: the manuscript. The conclusion reflects on the influence of printed books on lay devotional practice. Did the printing press and the ability to produce richly illustrated texts relatively cheaply modify practices of devotion? Closely related to the latter question is the more general issue of the influence of print on visual and textual culture in the decades before the Reformation.

The Devote ghetiden: Structure, Contents, and Woodcuts

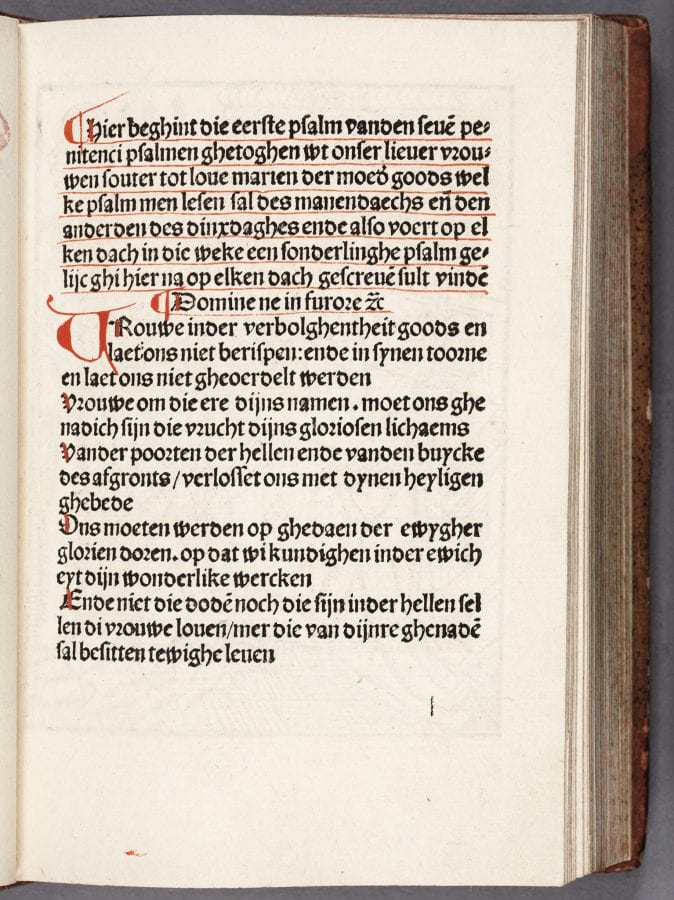

In the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (British Library) most editions of the Devote ghetiden are catalogued as “Horae [Dutch] Devote getijden van het leven Ons Heren.”11 In reference works such as Dutch Art: An Encyclopedia the text is similarly named “Devote ghetiden (book of hours).”12 Even a cursory reading, however, reveals that the Devote ghetiden is not a Dutch version of the traditional book of hours. The book starts with a prologue and continues with texts that are divided over the seven days of the week (see Table 1). The lion’s share of the texts is not related to the traditional paraliturgical texts in books of hours (calendar, Hours of the Virgin, Hours of the Cross, etc.), and none of the texts is structured according to the canonical hours.13 For each day there is a chapter that starts with a meditative text on, respectively, death, the Last Judgment, hell, the love of God, the Passion of Christ, confession, and heaven.14 The meditative texts are followed by one of the seven Penitential Psalms, the only textual element that is traditionally also a fixed component of books of hours, but here the Psalms appear in an extended version that combines exegesis and contemplative considerations. The Devote ghetiden continues with a prayer to the Trinity (related to God’s creation of that day) and a number of prayers (five to twelve a day) on the Creation, the Fall of Man, and the Life, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus Christ. Together these prayers form a prayer cycle on the history of salvation.15 In each chapter these prayers are followed by a short psalm taken from the Psalter of Our Lady (Souter OLV), the Adoro Te prayer in Middle Dutch, and a prayer to All Saints. The latter two prayers conclude the exercise for each day of the week, but their texts and the accompanying woodcut of the Mass of Saint Gregory are found only at the end of the chapter intended for Monday. From Tuesday onward a reference telling the reader to leaf backward suffices.16 No indication is provided about the time of day the texts should be read or whether they should be performed in a single reading or split between, for example, morning, afternoon, and evening.

Table 1

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meditative text (MT) on Death | MT on Last Judgment | MT on Hell | MT on God’s gifts and love | MT on Passion | MT on Confession | MT on Heaven | |||||||

| Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | Penitential Psalm (extended) | |||||||

| Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | Prayer to Trinity | |||||||

| 7 prayers Creation – Marriage Mary x Joseph | 9 prayers Annunciation – Christ at temple | 9 prayers Baptism – Purification of the temple | 10 prayers Last Supper – JC before Herod | 10 prayers JC before Pilate – Raising of the Cross | 5 prayers Crucifixion – Anastasis | 12 prayers Resurrection –Last Judgment |

|||||||

| 1st Psalm Souter OLV | 2nd Psalm Souter OLV | 3rd Psalm Souter OLV | 4th Psalm Souter OLV | 5th Psalm Souter OLV | 6th Psalm Souter OLV | 7th Psalm Souter OLV | |||||||

| Adoro Te(AT) and Prayer to All Saints (PtAS) | Reference to AT and PtAS | Reference to AT and PtAS | Reference to AT and PtAS | Reference to AT and PtAS | Litany of Our Lady, Reference to AT and PtAS | Reference to AT and PtAS; 2 extra prayers |

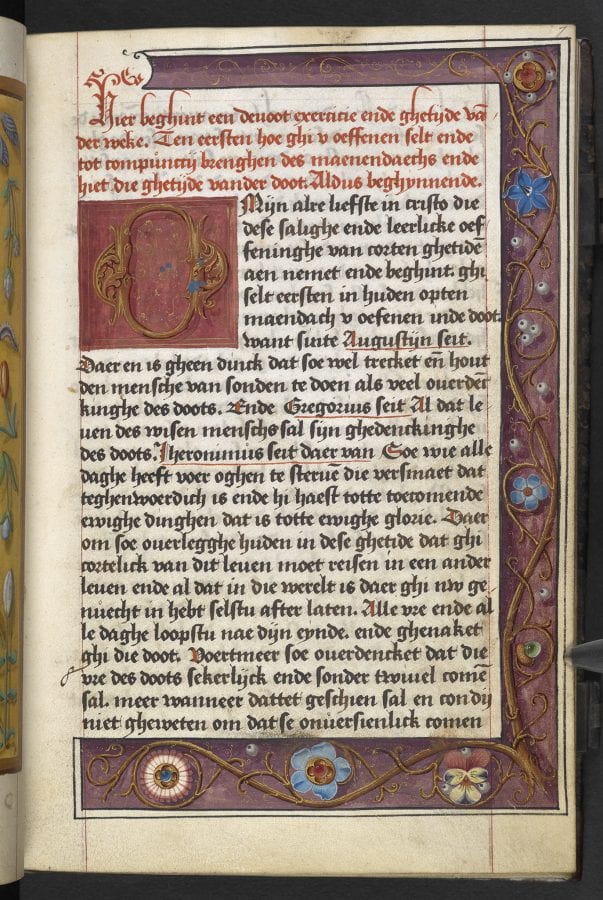

The Devote ghetiden thus combines existing, popular texts such as the Adoro Te prayer and the Penitential Psalms with new, non-standard texts: the meditative texts and the prayer cycle on salvation history.17 The person who collected the materials and whose voice is clearly recognizable in the prologue discussed below was probably responsible for the latter texts. Therefore, I will refer to him as “author-compiler.” This author-compiler could also be held accountable for the profound confusion in modern scholarship of his work with the traditional book of hours. In the prologue, in which he explains to the reader why this book was made, how it is structured, and for what it is beneficial, he refers to the text as (corte) ghetyden ([short] hours).18 For the author-compiler the meaning of ghetide (hour) seems to have evolved into a “[daily] contemplative exercise” not necessarily related to the canonical hours and/or the texts traditionally recited at those times of the day.19 This corresponds with the observation that with the advent of printing the liturgy—the main instrument used by the Church to guide the spiritual life of the laity—was becoming less dominant and other texts were used more freely.20 In the texts themselves the author-compiler refers to the meditative texts as ghetiden (hours): on Monday, for example, the votary is asked to “overlegghe huden in dese ghetide dat ghi cortelick van dit leven moet reysen in een ander leven (consider now in this hour that you will shortly have to travel from this life to another).”21

The prologue provides more clues about the background of the author-compiler. One of the few scholars to have dealt with the contents of the Devote ghetiden in more detail, the Antwerp Jesuit Léonce Reypens, focused on this introductory text.22 According to him the prologue completely disregards the monastic way of life and was written by an educated author, a secular priest well versed in scripture, the church fathers, and spiritual life.23

The prologue emphasizes that good works are impossible without Christ and that man—unlike animals—is gifted with reason so that he can distinguish between good and bad. To reach eternal joy in heaven one should strive to the most perfect state possible in earthly life, for which the author mentions two options: contemplative life, with a reference to Christ’s words to Martha about her sister Mary in the Gospel of Luke (“Mary has chosen the better part,” Luke 10:42), and the priesthood (die priesterlike staet).24 It is the latter more than the former that serves as a model for lay religiosity. Inspired by the priests’ daily celebration of the Mass, focusing on the dead (Monday), the Holy Trinity (Tuesday), the Holy Spirit (Wednesday), the Holy Sacrament (Thursday), the Holy Cross and the Passion (Friday), the Virgin (Saturday), and reconciliation with God (Sunday), the author-compiler has arranged three “points” in this book for laypeople.25 Those who want to live a life that will surely lead to perfection—that is, to eternal life—should read these texts on a daily basis: first, a meditative exercise that will prod the reader to repent his sins and incite his fear of God, second, a Penitential Psalm in expiation for the reader’s wrongdoings, and third, prayers to obtain God’s grace and praise him for all his benefactions and ineffable love.26

The author-compiler was fully aware of the needs of the laity and tailored his work specifically to their needs, as he himself explains:

Want ouermits dat die menschen int ghemeen inder werelt staet int werkelike leuen hem veel tijts becommeren ende onledich maken myt haer neringhen, ambachten of comenscappen, soe en hebben si niet wel die tijt of die macht die seuen ghetyden alle daghe te houden. Daerom sijn hier gheordineert seuen corte ghetyden van die geheel weke, daer elck dach sijn sonderlinghe compunctie, sonderlinghe ghebet der penitecien ende sonderlinghe ghebeden ende ghetyden heeft.

(Because in general people who live in the world and participate in the active life spend a lot of time bustling about their livelihood, trade or business, for which reason they do not have the time or the strength to keep the seven hours [i.e., the canonical hours] every day. Therefore here are set out seven short hours for the whole week where each day has its specific [act of] remorse, specific penitential prayer and specific prayers and hours.)27

In a businesslike manner befitting the mindset of his audience the author assures his readers that whoever adopts this exercise and keeps the “hours” as set out in the book will achieve three results: (1) the reader will have the strength to resist the devil, the world, and all sinful desires, (2) will reach an inner consolation in his or her soul that will empower the reader to acquire a “godly taste” for scripture and for heavenly things, better understand and remember all sermons—however ingenious they may be—and in confession properly discern between deadly and daily sins, and last but not least (3) in the hereafter he or she will be raised up on high by God in eternal life together with the angels.28 The author-compiler consciously offered his readers an alternative book of hours that enabled them to integrate spiritual exercises efficiently into the commotion of everyday life, to gain thorough knowledge of matters of the faith, and indeed to reach results comparable to—if not better than—traditional forms of devotion. Furthermore, the texts are gender neutral and thus suitable for both male and female readers, allowing the printers to find a large audience.

The undeniably lay character of the readership may also explain the small numbers and incompleteness of the surviving copies of the Devote ghetiden, as the books would have been kept in private possession and used in households.29 While the book’s primary use would have been for individual silent prayer and contemplation, one can easily imagine that they might have been used for education of the young, especially the images showing the main events in the history of salvation. Furthermore, the books offer simple modes of prayer to illiterate members of the household.30

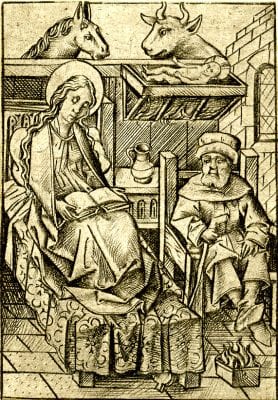

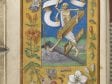

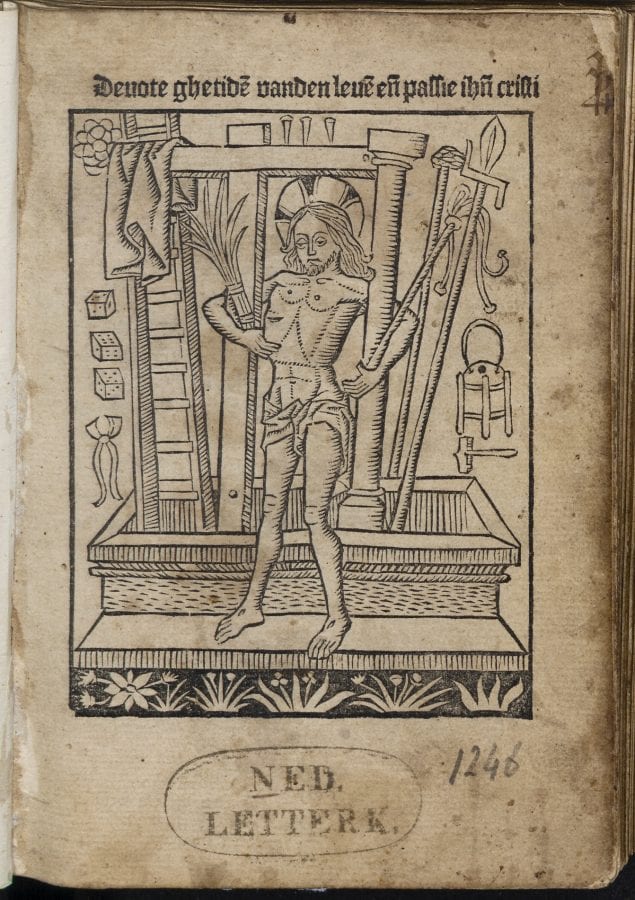

The first woodcut the late medieval reader of the Antwerp edition of the Devote ghetiden encountered is an emblematic image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows on the title page (fig. 1). The title above the image, introducing the text as Devote ghetiden vanden leven ende passie Ihesu Christi, positions Christ’s life as the main principle underlying the order of the daily spiritual exercises, which in itself should have made modern readers suspicious as this suggests a different arrangement than that of a traditional book of hours. Interestingly, the prayer cycle on salvation history is positioned as the principal component of the book, while as we have seen above the prayers on this subject were placed between a range of texts addressing various different subjects. Only the meditative text on Friday focuses on the Passion, and here the same woodcut of the Man of Sorrows is used. The fact that Christ’s Passion is central to the title page might have been part of Leeu’s commercial strategy, which sought to take advantage of the fifteenth-century popularity of the Life and Passion of Christ. Looking at the title page the reader got a taste of what was to come: full-page woodcuts that give central stage to the leading figures, placing them in the foreground, while providing enough detail to evoke an imaginative visual experience and structure the process of prayer.31

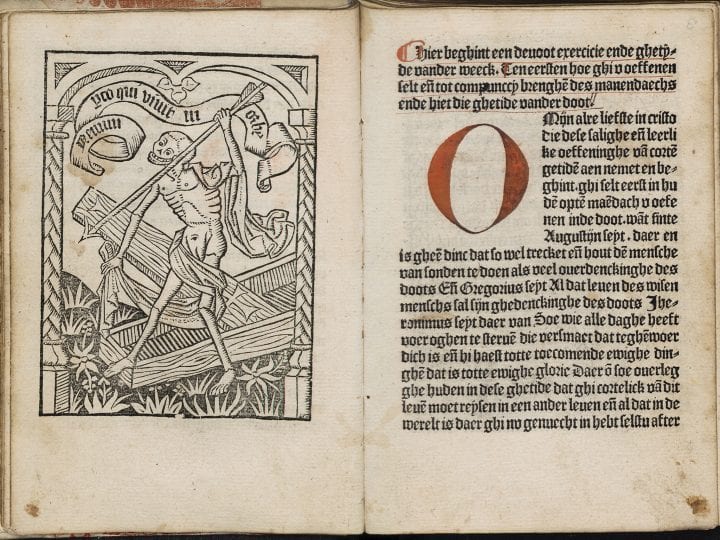

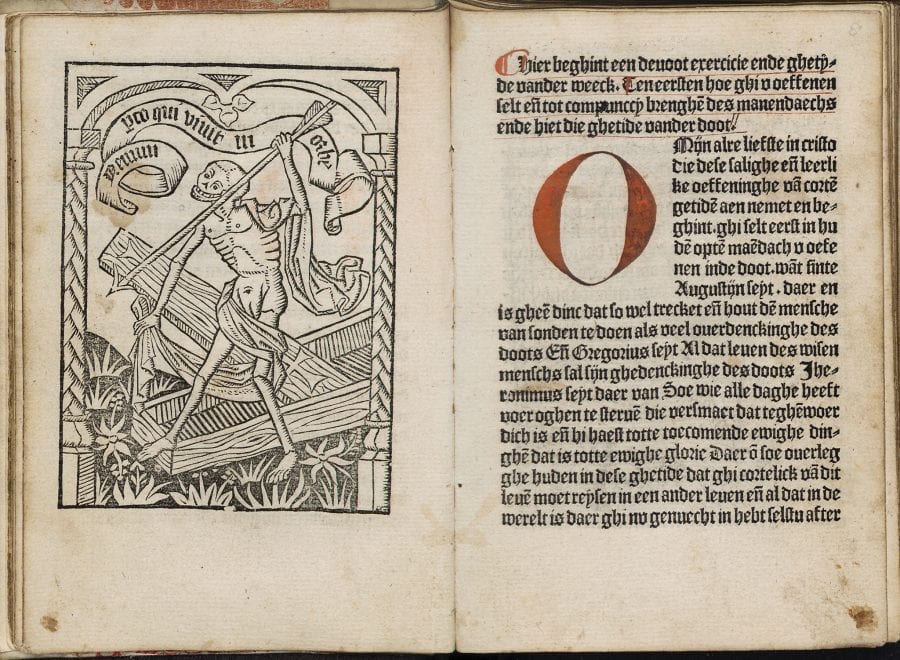

The next image the reader of the Devote ghetiden encounters is the image of Death, which is placed next to the opening of the first meditative text, to be read on Monday (fig. 2). All of the meditative texts at the start of each chapter are accompanied by images depicting the contemplative subject for that day. Apart from structuring the text and enabling readers to find a certain section more easily,32 these images appear to have two main functions: they announce the subject of the day to the readers and prepare them for reading and subsequently ruminating upon the text. It is the woodcut that influences their initial disposition and mental state. In this case Death is presented as a personification, which turns the relatively abstract notion of death into an active actor, a real and present peril. The words in the banderole, “Nemini parco qui vivit in orbe (I spare no one who lives in the world),” not only create a dialogue between text and image, bringing death to life, they also initiate an interaction between the reader (it is the reader to whom Death speaks) and the meditative subject of that day. Death’s statement demands a reaction from the reader—not a literal response but an internal reflection: how does the reader deal with the feelings the image arouses and what stance does he or she take? Are readers prepared for their own personal confrontation with Death?

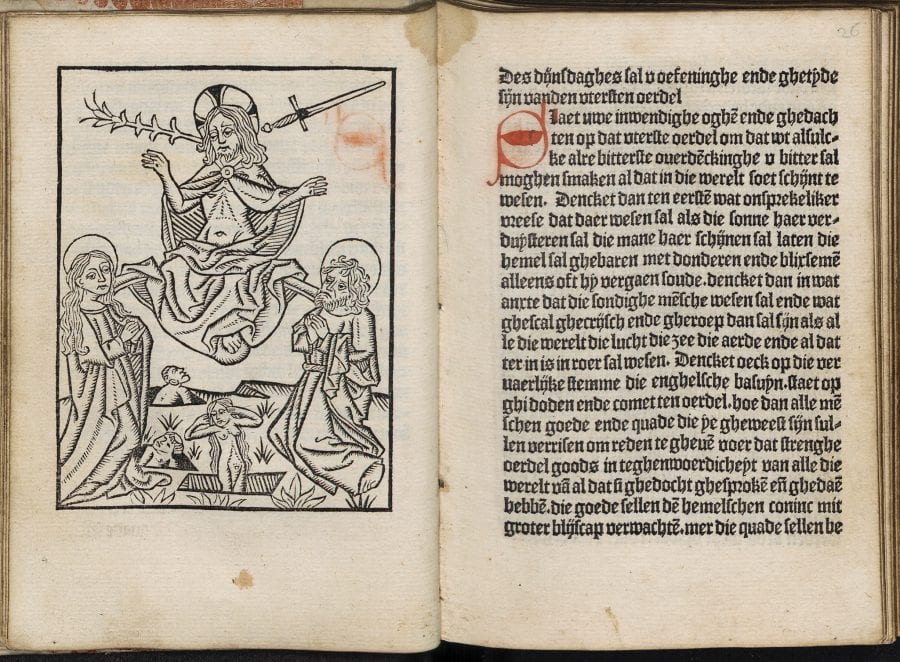

The woodcuts at the start of each of the meditative texts also stimulate the reader’s visual imagination, in particular the ability to visualize abstract notions and future and past events. The texts themselves make a strong appeal to this capacity. The meditative text for Tuesday, for example, starts with an appeal to the reader—after he/she has been faced with a fairly conventional image of the Last Judgment (fig. 3) on the left side of the opening—to “cast his inner eyes and thoughts on the Last Judgment so that such a mournful contemplation might make all that seems sweet in the world taste bitter to you.”33 The events that will take place during the Last Judgment are described in minute detail, with a strong focus on feelings, making the meditative exercise both visual and emotional. Through the description the reader “sees” and experiences everything—from the indescribable fear that will be caused by the eclipse of the sun and the heavenly signs of lightning and thunder, to the great timidity, shame, trouble, and disgrace of sinful people before the severe judge when the books containing all the thoughts, words, and deeds of every individual will be opened and read in the presence of the entire world. Everything that is now hidden from the eyes of men will be revealed and everyone will have to account for everything he or she has omitted to do and has done. The feeling of desperation all sinners shall experience is emphasized by a direct address to the reader, as if he/she were standing before the judge: “if you would want to deny something, you may do so, but God and the angels have seen everything, and especially your guardian angel will testify against you.”34

To fully convince the reader of the need to avoid such a fate, he/she is made to “inwendelike voelen ende bekennen (feel and acknowledge internally)” the disgrace and fear felt by sinners during the Last Judgment by visualizing (“stelt die voer u ogen [put before your eyes]”) a more familiar scene: if caught for robbery or another crime and brought before the court, the reader would not be able to face the people without great shame and disgrace, especially those he or she knows. Imagine what great shame there will be when all the crimes of sinful people are shown for the entire world to see. The author exclaims that no one can consider this and then go on sinning, except for someone who is “dul ende sinneloes (foolish and senseless).”35 At the end of the meditative text for Tuesday readers are once more exhorted to take responsibility for their own souls:

Oordelt nu u selven, bekent u scult, hebt rou ende voldoet, want dan en sal niet genoechliker wesen dan een zuver conscienci. Wilt nu van sonden wel ghenesen, soe ontgae di die scarpe bitter sentenci daer ons God wel voer sal bescermen, ist dat wij ons selven nu willen ontfermen. [my italics]

(Now judge yourself, admit your guilt, repent and make good, because then [at the Last Judgment] nothing will be more pleasant than an unspotted conscience. If you are willing to be cured from sin now you will escape the severe bitter sentence from which God will protect us if we take care of ourselves now.)36

It is important to notice that even though the entire text is printed as prose, the original Middle Dutch text makes use of rhyme. This is only one of many rhyming passages in these meditative texts, but a more detailed analysis would go beyond the scope of this essay.37 In this instance the rhyming scheme ababcc might have helped the reader to memorize the core advice and carry it in his/her mind during the course of the day (if we assume the texts were read in the morning). The first words of a similar passage with a more elaborate rhyming scheme (ababbcbccdd) at the end of the text describing the pains of hell (Wednesday) seem to confirm such a mnemonic use of the verses: “Dit set en hout in u memorie (Put and keep this in your memory).”38 The frequent use of rhyme and the various rhyme schemes employed might confirm that the author was well educated. They might also point to an affiliation or at least familiarity with circles of early “rhetoricians” in Holland or further afield in Flanders.39 This is not surprising as early printers played a crucial role in introducing the work of the late medieval Dutch “rhetoricians” in the Northern Netherlands.40

Initially the woodcuts at the start of these texts served to structure the book, to introduce the subject matter of the day, and to arouse the emotions and stimulate the reader’s visual imagination. As the votary practiced the exercise of the Devote ghetiden week in, week out, the function of the images would have gradually altered. While upon a first reading the woodcut of Death might provoke feelings of fear and uncertainty, in later stages the knowledge conveyed by the meditative text would have strengthened the reader’s consciousness about the state of his/her own soul, enabling the reader to appreciate the temporary proximity between him/herself and Death and taking the opportunity to reiterate the main points of the text in the face of Death. Having likewise contemplated the detailed description of the events during the Last Judgment a number of times, the fairly simple woodcut would have sparked a most lively image in the votary’s mind, comparable to an elaborately layered painting expressing the horror, fear, and shame of sinners, but also the joy of the righteous and the way to work toward joining the latter. Gradually the reader might have also become accustomed to associating the image with the verses he or she had memorized and might recite (mentally or orally) the aide-mémoire upon viewing the image in the book—or when faced with a similar image in the public space, for example, in a church or a governmental building.

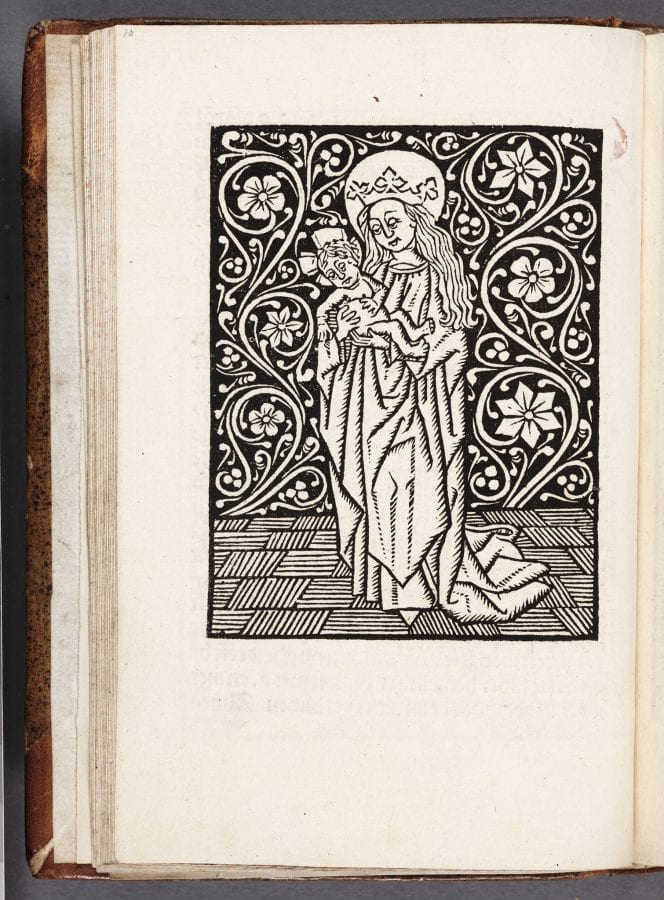

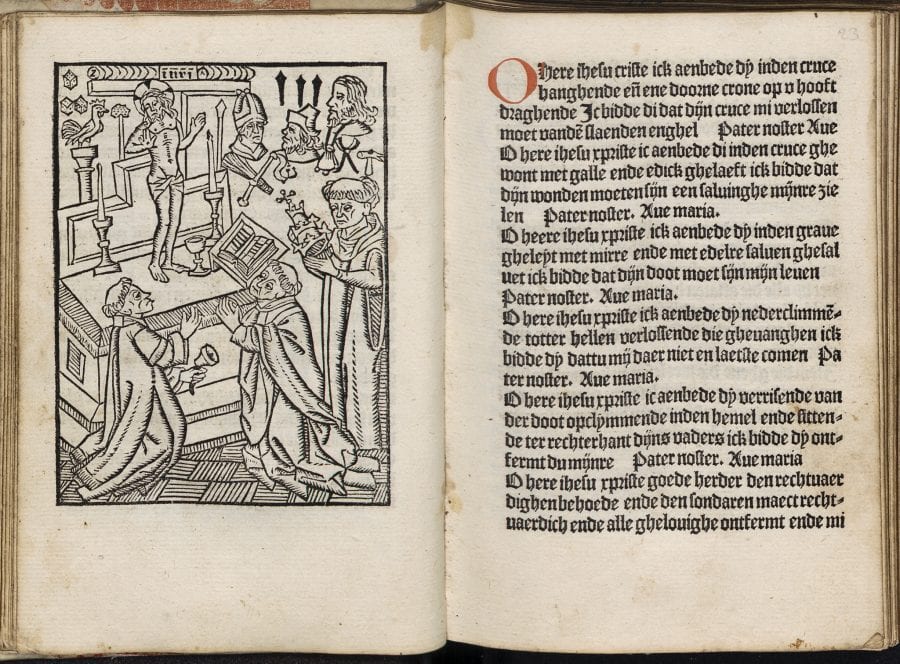

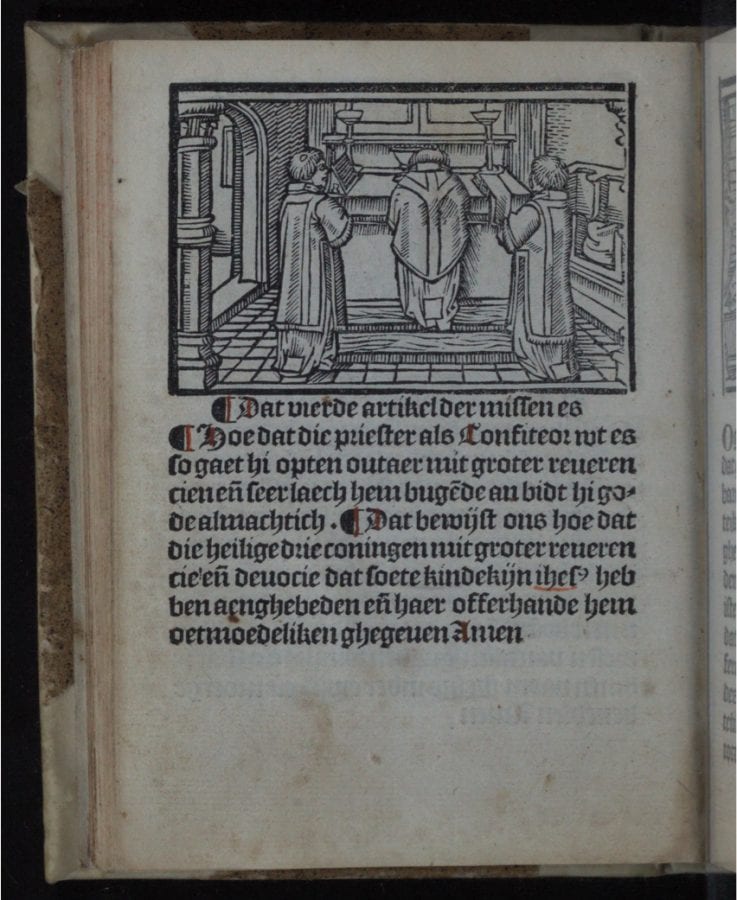

The prayers to the Trinity, the short Marian psalms, and the Adoro Te prayer are accompanied by woodcuts with emblematic devotional imagery.41 The images of the Gnadenstuhl, Mary clothed with the sun and standing on the crescent moon, and the Mass of Saint Gregory had a strong (supernatural) efficacy of their own, and their very presence was a necessary precondition for successful performance of the prayers. In order to activate the indulgences attached to the Adoro Te prayer, the reader was required to have a material image of the Mass of Saint Gregory in front of him/her (fig. 4).42 According to Kathryn Rudy such an image allowed the reader to engage with the Mass and confirm his/her belief in transubstantiation, making the votary eligible for obtaining the indulgences.43 In fact, the woodcut and the experience it evoked seem to have been more powerful than the text, because illiterate persons who recited the words of the Pater Noster and Ave Maria in front of the woodcut—instead of reading the Adoro Te prayer—acquired the same indulgence.44

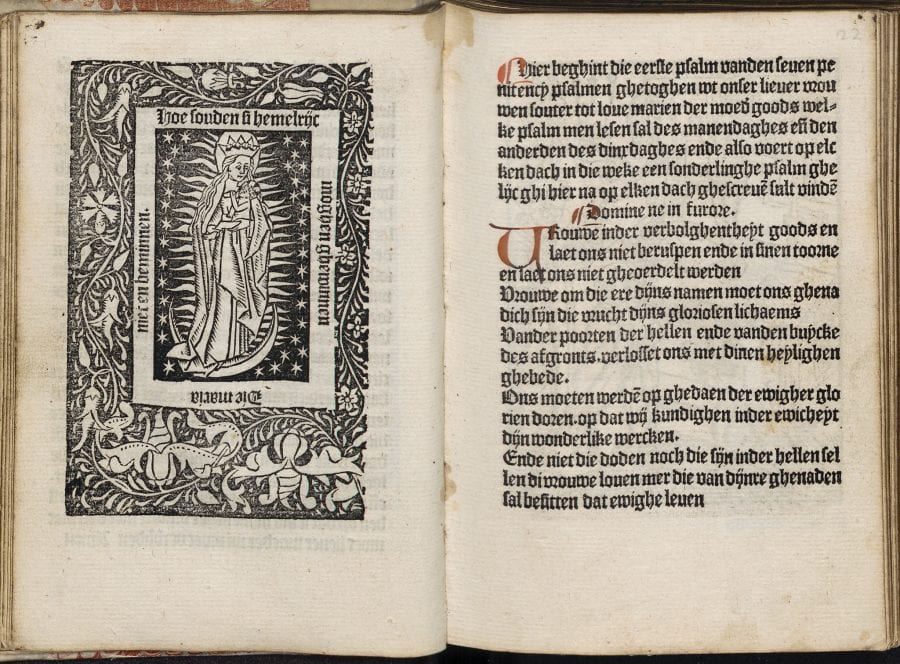

Similarly the image of Maria in Sole—omnipresent at the end of the fifteenth century in the Netherlands and often combined with Marian prayers—was most probably required to gain the indulgences attached to the Marian psalms taken from the Psalter of Our Lady (Souter OLV).45 For this reason Leeu discarded another woodcut that was originally part of the series, Mary with the Christ Child against a decorative background, and replaced it with the woodcut that depicts the Virgin on the crescent moon (fig. 5a, fig. 5b and fig. 6).46 The verse surrounding Mary, “Hoe souden si hemelrijc moghen ghewinnen / Die Maria niet en beminnen (How may they earn heaven, those who do not love Mary),” might have functioned in a similar way to the rhyming passages in the meditative texts. The necessity of having the image before one’s eyes when reading the prayers is also the reason why this image is repeated seven times in the book. As the same is done with the Gnadenstuhl image we might assume that this woodcut fulfilled a comparable function.

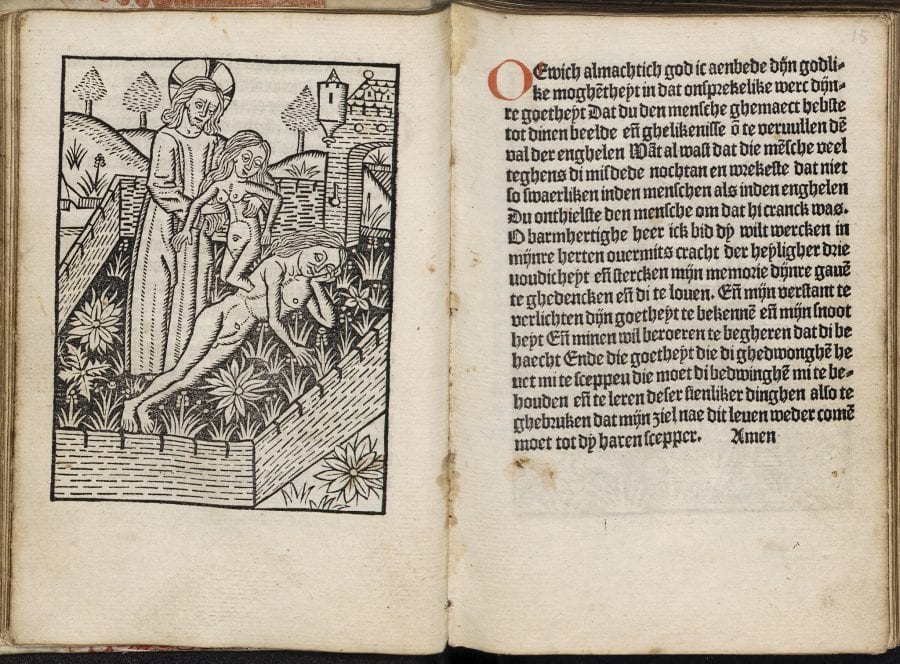

Yet another kind of text-image relationship can be found in the prayer cycle on the history of salvation, inserted each day of the week between the prayers to the Trinity and the Marian psalms. In these sections the images appear to function in close relation to the meditative prayers as instruments that allow the readers to engage in the spiritual practice of the imitation of Christ; a process of prayer intended to reform their soul in his image.

A Pictorial and Verbal Prayer Cycle on the History of Salvation

The fifty-two meditative texts of the prayer cycle transform the events of the history of salvation into models the soul can emulate. All prayers are accompanied by a full-page image. Image and text face each other, evoking the sense of a succession of image-and-text diptychs (fig. 7).47 A similar diptychlike arrangement of text and image can be found in other early printed books such as the Boexken vander missen (Booklet on the Mass) by the Franciscan Observant Gerrit van der Goude, where pictorial images and allegorical explanations of the acts during Mass are faced by meditative prayers and woodcuts depicting events from Christ’s life (fig. 8a, fig. 8b).48 The inclusion of images in such texts—one of the major advantages of the printing press that was commercially exploited by printers—altered not only the process of knowledge transmission but also devotional practice itself in that religious information was presented in an increasingly visual mode.49

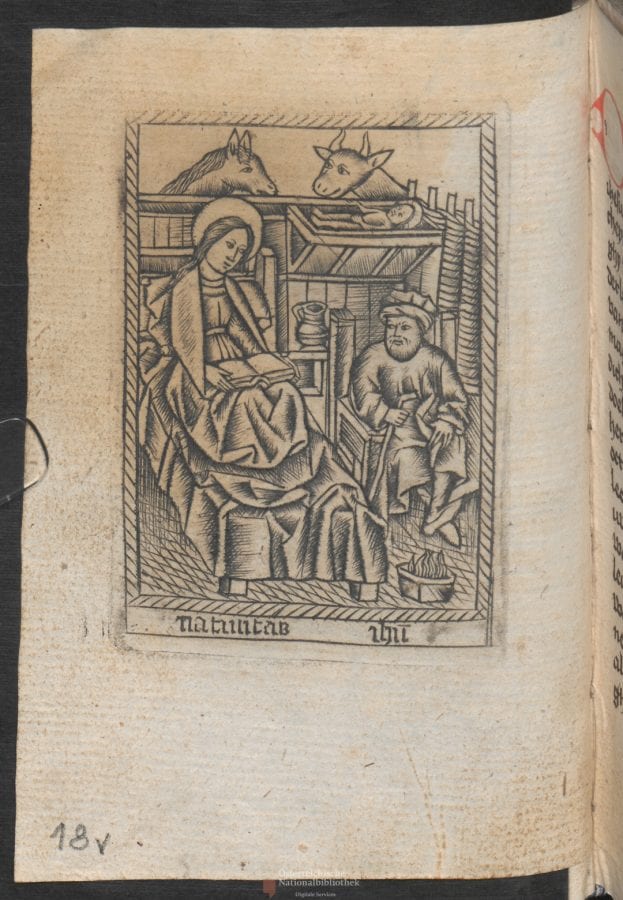

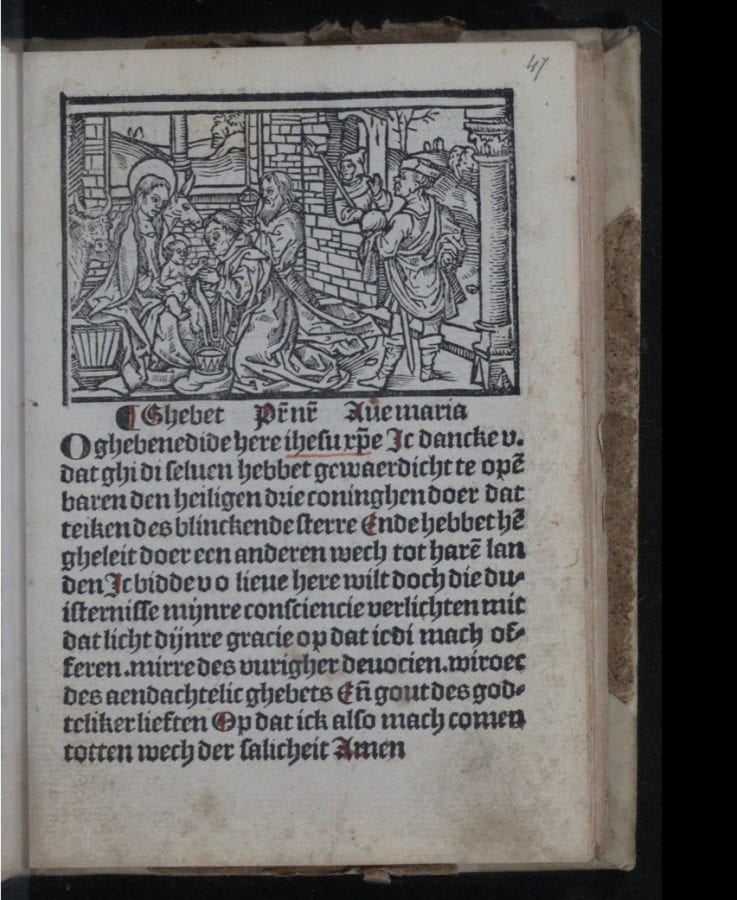

The Devote ghetiden and the prayer cycle in particular present an excellent example of how an unprecedentedly large amount of pictorial material could be integrated into the practice of prayer. Each opening—each unit of text and image—allowed readers to engage in a meditation that fully combined text and image: as they moved their eyes back and forth between woodcut and prayer, the image served to deepen their meditative prayer based on the text. All prayers in the cycle on the history of salvation follow a similar structure: the votary addresses the Godhead or Christ in a way that is in keeping with the event, speaks words of gratitude, and then reads a brief description of the event, which is also shown by the image. The votary then moves on to make a request—always connected to the spiritual model provided by the description of the event. To study the function of these texts and the accompanying pictorial images as spiritual instruments in more detail, I will discuss three examples from different episodes of Christ’s life: the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 9),50 the Crucifixion (fig. 10),51 and the Supper at Emmaus (fig. 11).52

The first prayer addresses Christ as the “king of kings, lord of lords and prince of princes (O coninc der coninghen, o heer der heren, o prins der princen)” and describes how his birth was revealed to the shepherds by an angel and to the three kings by a beautiful, miraculous star.53 This event is turned into a model for the soul’s reformation as the votary prays to Christ through the “deep, wonderful humility (diepe, wonderlike oetmoedicheyt)” he has demonstrated and taught us through this example: even though the Son of God was born in the poorest of circumstances, in a humble, smelly beast’s shed, he did not shy away from revealing his birth to the rich and powerful kings who came loaded with precious gifts and a fierce desire to honor him.54 The votary pleads that he may follow Christ’s meekness, never again regard himself highly but instead with these kings offer Christ love (gold), devout prayer (incense), and meekness (myrrh).

The close association between text and image suggests that before, while, and after reading the prayer, the votary could have moved mentally through the accompanying woodcut a number of times, focusing on different aspects of the image. Starting with the Christ Child who is revered as a king by the Magi—underpinning the initial words of the prayer—and then moving to the star, which is prominently shown in the sky as a symbol of Christ’s meekness. The king standing next to Mary seems to make a blessing gesture that points to the star as if to direct the viewer’s attention toward Christ’s honorable deed of revealing his birth. Moving back to the group in the foreground the votary would have contemplated the Christ Child, sitting naked on his mother’s lap in front of their humble dwelling, while the richly attired kings offer him their gifts. Toward the end of the prayer, the image would have aided the reader in adopting the perspective of the kings: by focusing on the king who has laid his crown—the symbol of his status—on the ground and kneels before Christ, the votary would have inwardly laid off his pride and assumed a humble position (“dat ic die oetmoedicheyt moet navolghen ende nymmermeer my selven en moet … goet achten [that I may follow this meekness and never again regard myself favorably]”), subordinating himself to Christ and sinking into prayer with the kings (“Mer dat ic met desen heylighen coninghen u offeren moet gout der minnen, wyeroeck des devoten ghebedes ende mirre der oetmoedigher ghestorvenheyt [But that I, with these holy kings, may offer you gold of love, incense of devout prayer, and myrrh of submissive meekness]”). Finally, the vessels the kings hold in their hands represent the votary’s gifts to Christ—love, devout prayer, and meekness.

The prayer that accompanies the Crucifixion with Mary and John the Evangelist (fig. 10) starts with the votary thanking God for his “pitiful hanging (deerliken hanghen)” for three hours on three blunt nails.55 The votary then prays to the Lord:

Ic bid u, liever heer, dat die aenmerkinge mijnre groter sonden, der ewigher hellen die ic soe dic daer mede verdient heb ende des bitteren doots die ghi daer voer gheleden hebt als drie naghelen mi altoes vast anden cruce der penitencien houden moghen.

(I pray to you, dear Lord, that the consideration of my heavy sins, of the eternal hell that I earned through them so often, and of the bitter death that you have suffered for them, may keep me firmly secured to the cross of penance as [if they were] three nails.)56

The three nails are clearly visible in the woodcut as large black iron pins piercing Christ’s hands and feet. Having elaborated on this aspect, the votary returns to Christ’s Crucifixion and thus to the events that preceded the pictorial scene before his/her eyes. The votary asks God to lend him/her the grace to forgive all those who have done the votary wrong, to pray for them, and to be merciful to all sinners, just as Christ prayed for those who crucified him and promised paradise, exemplifying perfection, to one of the robbers. Focusing on John and Mary, who appear on Christ’s left- and right-hand sides, the votary requests that Christ entrusts him/her to his dear mother, just as he had entrusted her to John.57 The votary also asks to be granted a desire equal to the yearning with which Christ longed for our salvation: “And just as you desired our salvation, so grant me, dear Lord, to truthfully desire to fulfill your will (Ende also als u dorste na onser salicheyt, also verleent mi lieve heer warachtelic te dorsten uwen wil te volbrenghen).” At the end of the prayer the votary expresses the wish that when all has been accomplished the votary may lay his/her soul in his hands (“that I may proffer my soul in your hands [dat ic mijn ziel dan offeren mach in uwen handen]”), echoing Christ’s last words and possibly also alluding to John resting on Jesus’s bosom during the Last Supper.58

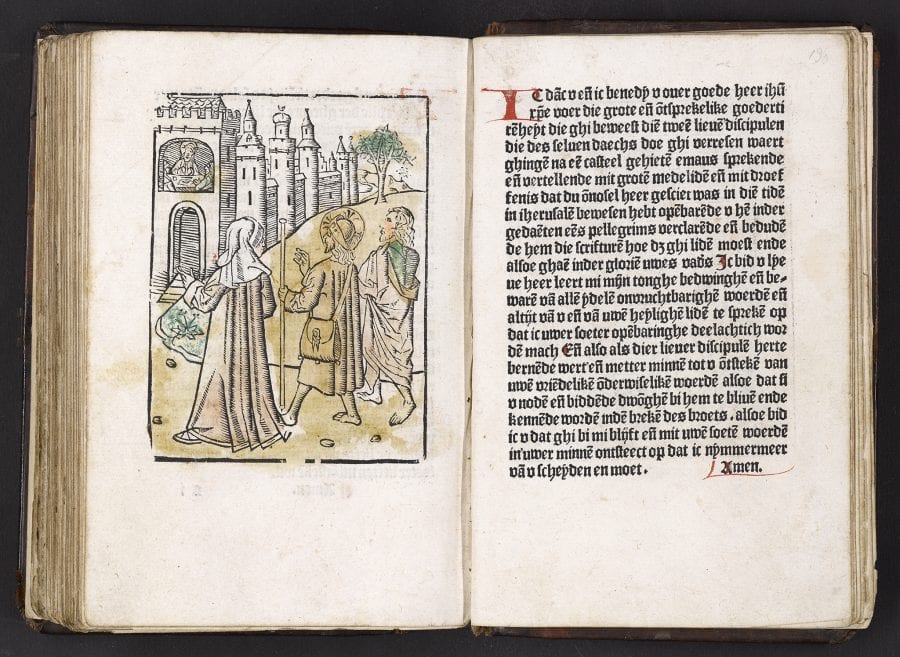

In the prayer positioned next to and thus interacting with the woodcut showing the Supper at Emmaus (fig. 11), the votary thanks Christ for the inexpressible kindness and compassion that he showed the two disciples who on the day of the Resurrection were on their way to Emmaus, talking about what had happened at Jerusalem. Christ revealed himself to them in the guise of a pilgrim and explained scripture and his own suffering to them.59 Halfway through the prayer, the votary asks Christ for help:

Ic bid u, liever here, leert mi mijn tonghe bedwinghen ende bewaren van allen ydelen onvruchtbarighen woerden ende altijt van u ende van uwen heylighen liden te spreken op dat ic uwer soeter openbaringhe delachtich mach worden.

(I pray to you, dear Lord, teach me to suppress my tongue and to keep it from all idle, fruitless words and always to speak about your holy Passion so that I may partake in your sweet revelation.)60

Just as the hearts of those dear disciples were inflamed with love through Christ’s friendly words, which made them press Christ to stay with them (“dat si u noden ende biddende dwonghen bi hem te bliven ende kennende worden inden breken des broots [that they invited and compelled you to stay with them and became knowledgeable in the breaking of the bread]”), so the votary yearns for Christ, “also bid ic u dat ghi bi mi blijft ende met uwen soeten woerden in uwer minnen ontsteect (so I pray to you that you stay with me and ingnite in me your love with your sweet words).” In that way the votary will never again have to part from God. The woodcut connects closely with the end of the prayer, describing Christ breaking bread. The text first takes the votary back to the events preceding the scene portrayed. In his/her meditative prayer the votary could mentally travel to Emmaus and enter the intimate, homely space depicted in the woodcut through the porch on the right, possibly identifying himself with the disciple standing next to the door. He could partake of the supper, sit at the table, become inflamed with Christ’s sweet words, look up to Christ through the other disciple, see his true nature, and long always to stay with Christ in this room. Having read the prayer on the right-hand page, the votary could move his eye back to the image and contemplate further his desire for the intimate closeness to Christ expressed in both prayer and image.

Although the images that illustrate the prayer cycle are conventional compositions that stem from a long pictorial tradition, when placed next to prayers containing meditations on these specific events that connect them to the state of the votary’s soul, they function as spiritual instruments in dialogue with the text. The text highlights specific aspects of the image and in turn the latter initiates, deepens, and further develops the reader’s meditation, stimulating his/her imagination such that he/she becomes mentally present in the scene and thus in more direct contact with God. In the Devote ghetiden as a whole these prayers and images serve a well thought-out function. As the author-compiler himself explains in the prologue, the meditative texts at the start of the day and the subsequent psalms were meant to make the reader repent his sins. The prayers then served as a way to obtain God’s grace.61 The Devote ghetiden thus engage the reader in a thorough program of reformation of the soul.62 The images and contemplative texts at the start of the day serve to stimulate the soul’s awareness of its spiritual condition. They strengthen the reader’s awareness of what can go—and has already gone—wrong and the consequences he/she will have to face if no actions are taken. Once the soul is drawn away from sin and cleansed by reading the Penitential Psalm, it is ready to be formed according to Christ’s example. The visual narratives and meditative prayers offer positive models the soul should strive to emulate. The prayers and images stimulate the votary to visualize and enter mentally into the events of salvation history, offering the soul models by which to renew itself, returning to its original state, when it was created in the image of God.

Changing the Scene, Altering the Experience: Variations in Print and Manuscript

In late medieval book production the relationship between text and image was by no means fixed. As woodcuts were frequently reused, recut, and combined with blocks from other series, the same text could take on a close relation to more than one image, or the other way around: the same image could easily take on a fruitful dialogue with a completely different text, especially when the author of the new text knew the image, although this did not have to be the case.63 Furthermore, text and image were not fixed to a single medium. It has often been acknowledged that the transition from manuscript to print was a gradual process during which both media functioned side by side. Quite a few examples of manuscripts containing transcriptions from printed editions and of manuscript illuminators using prints as inspiration for their work have been uncovered, but usually the interplay between manuscript and print is discussed separately for text and image.64

The fact that the Devote ghetiden also circulated in manuscript form has not to date been noted in research and provides an intriguing case for the study of the transfer of text-image units from print to manuscript (and possibly vice versa). Seven manuscripts, all dated at least a couple of years after the first printed edition, contain (parts of) the Devote ghetiden.65 The prayer cycle on the history of salvation proved to be the most popular part of the Devote ghetiden, at least parts of it being included in all seven manuscripts. In 1978 Philip Webber, unaware of the circulation of the cycle in the printed editions of the Devote ghetiden, edited the prayer cycle as an independent text on the basis of a manuscript at Princeton (Princeton University Library, Garrett Ms. 63).66 Cornelia van Wulfschkercke (d. 1540), a nun at the Carmelite convent of Sion in Bruges, produced this codex for her own devotional practice in the early sixteenth century.67 Webber’s major argument for this manuscript’s originality was “its terse style,”68 but this seems in fact to have consisted of abbreviations and changes, possibly made by Cornelia herself, to the Devote ghetiden. The fact that the large majority of the seven manuscripts contain further texts from the Devote ghetiden69—usually combined with yet other texts—is an additional indication that Cornelia most probably extracted the prayer cycle from the Devote ghetiden. Cornelia’s manuscript is exceptional not only because it contains none of the other texts from the Devote ghetiden and slightly abridged versions of all the prayers but also because it was the only manuscript made by a professed religious person.70

Focusing mainly on the prayer cycle the final section of this essay explores the complex transmission of text and image between print and manuscript and the changes in text-and-image relations insofar as they lead to a different reading and/or an alternative meditative experience.71 Such an exploration can point to a number of patterns that occur when a verbal-pictorial narrative was not only produced by printers but also circulated in manuscript.

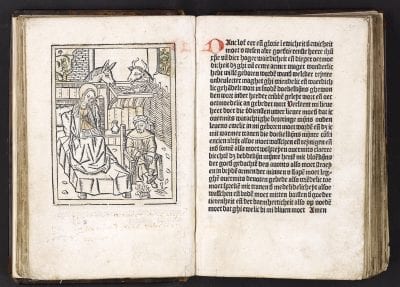

First, let us stay within the boundaries of printed book production. As mentioned above, copies exist of five printed editions of the Devote ghetiden and further editions (of which no copies have come down to us) are suggested by the existence of woodcut series that contain the full illustrational program of the text. The only edition of which a copy has survived that does not combine the text with Leeu’s woodcuts is the 1486 Haarlem edition by Jacob Bellaert.72 Even though Bellaert, a former apprentice of Leeu, borrowed printing material from his former master, for some reason he felt the need to have a new series of illustrations made for his edition of the Devote ghetiden.73 Some of Bellaert’s woodcuts differ considerably from Leeu’s illustrations. This can be partially explained by the woodcutter’s use of different models, as some compositions relate more closely to the Biblia Pauperum block book and engravings by the Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs, as is for example the case with the Nativity scene (fig. 12). Some differences, however, do not have precedents in earlier illustration cycles and might have resulted from a close(r) reading of the text. In turn, this changed the reading and focus of the votary’s meditative prayer.

The woodcut next to the Supper at Emmaus prayer, for example, changes the reader’s meditative experience considerably. The focus is not on the intimate scene of the disciples and Christ at the table (the tradition found in the work of Israhel van Meckenem and the Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs). In Bellaert’s woodcut (fig. 13) the actual meeting and the conversation between Christ and the disciples becomes the central event through which the reader’s mental presence is stimulated. The perspective of the image, Christ and the disciples are seen from the back, as if the viewer were standing on the side of the road, invites the onlooker to join the group and walk with them to Emmaus. The main focus is now on Christ’s lessons and the votary’s plea that he/she might open his/her mouth only to speak of Christ’s suffering. The actual supper is shown to the reader in the background of the image, clearly as an allusion to that earlier event. The strong sense of an evolving narrative within the image would have made the reader’s meditative prayer less static. Guided by the text the votary is able to move through the dynamic of the continuous narrative in the image and experience the various stages of the prayer more fully.

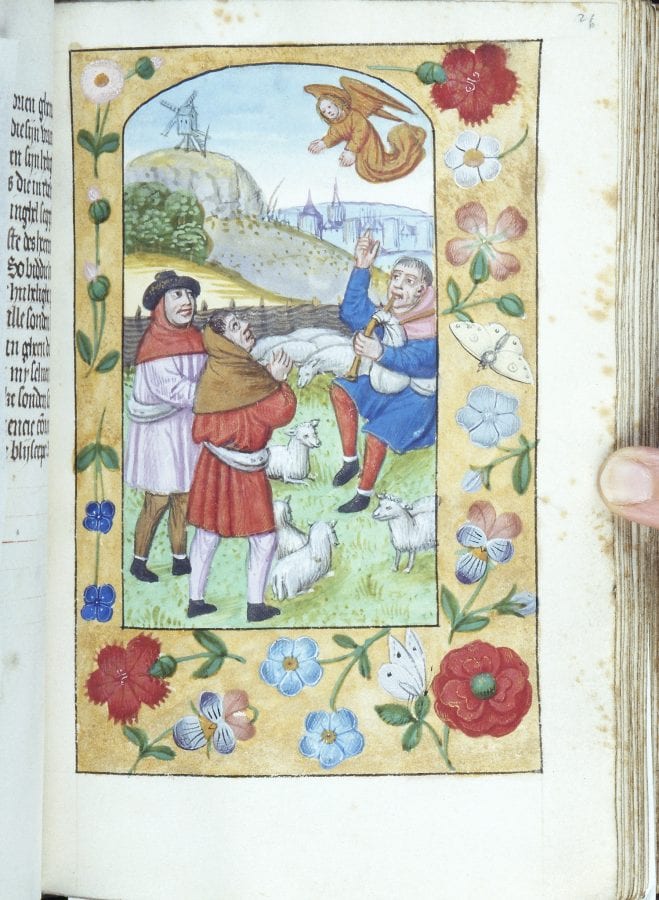

In manuscripts even more profound changes occurred in the way text and image interacted in forming the reader’s meditative experience and the renewal of his soul. On the one hand manuscripts offered more possibilities for customizing a text and tailoring a book to personal wishes. On the other hand, manuscript illumination not only had its own conventions, it was still relatively expensive and the inclusion of the same amount of visual material as was to be found in the printed editions of the Devote ghetiden, employing hand-painted miniatures on parchment, would have been very costly. This did occur, however, possibly when well-to-do laypeople of the upper echelons of society wished to integrate the exercises of the Devote ghetiden into their lives but preferred to do so by means of a lavishly decorated manuscript. An early sixteenth-century parchment manuscript at the British Library (Add. Ms. 20729), which has not previously been connected to the printed editions of the Devote ghetiden, contains the complete text illustrated with full-page miniatures and decorated with ornate borders (fig. 14).74 In the prayer cycle on the history of salvation the manuscript follows the same image-text diptych layout as the printed versions of the Devote ghetiden. An inscription on the inside of the binding, “Gulleelmo de Dene,” might point to a lay owner, probably from Flanders.75

In two other richly decorated parchment manuscripts, one illuminated by the Master of Cornelis Croesinck (The Hague, Royal Library, Ms. 135 E 19)—one of the Masters of the Dark Eyes76—and the other by the Masters of Hugo Jansz van Woerden (The Hague, Royal Library, Ms. BPH 79), the texts were probably adapted to the wishes of the patrons: both manuscripts contain the prayers to the Trinity, (most of) the prayers of the prayer cycle, and the psalms from the Souter OLV. The meditative texts at the start of each day and the Penitential Psalms are replaced by other devotional texts (Ms. BPH 79) or left out (Ms. 135 E 19).77 The former manuscript illustrates each prayer with a large washed drawing in a gold-leaf frame. Hinke Bakker has convincingly argued that they are based on a series of woodcuts made for Hugo Jansz van Woerden.78 The strict alternation of image and text found in the printed books is not maintained, however; when written by hand the prayers were apparently too long to fit on a single page. The prayers always start beneath the miniature and continue on the recto or verso page, depending on whether the miniature is placed on the verso or recto of a leaf. After the end of the prayer the page is left blank. This means that the reader was not able to move his eyes between text and image while reading the whole text of the prayer; or to connect aspects of the text to the image and let the image stimulate his meditation without having to leaf back. The images themselves, especially the ones that illustrate the Passion, evoke a meditation that is more focused on the bodily suffering of Christ: in the drawings Christ’s body is covered with drops, streaks, and streams of bright red blood (fig. 15).79

But it was not only the blood in the images that altered the focus of the votary’s meditation. The prayer accompanying the image of Mary and John beneath the cross in Leeu’s editions is replaced with a longer prayer (ca. 1,100 words) that starts with a description of Christ’s body stretched on the cross as a string drawn on a bow and hanging between two robbers (fig. 16). The reader’s intended focus on the three nails and on John and Mary is exchanged for meditations on the Seven Last Words Christ spoke from the cross. At the end of the prayer the following rubric appears: “Ende of yemant dit gebet alle dage lesen woude dair om isser int corte verhaelt wat sonderlinghes dat hier na volget in die twee ghebeden” (And in case someone might wish to read this prayer every day, therefore it contains a brief account of what is elaborated in the two following prayers). This prayer enabled readers who wanted to meditate on this central event in Christ’s Passion every day of the week to do so, providing them with more details and points to consider than the prayer in the printed editions. Again, just as in the Devote ghetiden, the epitome of late medieval lay spirituality seems to be an efficient spiritual exercise (i.e., “three prayers in one”).

The same prayer occurs in the manuscript illuminated by the Master of Cornelis Croesinck, which was probably made for a married couple (depicted on fol. 2v) and later owned by Anna Geperts.80 In contrast to the Masters of Hugo Jansz van Woerden, the Master of Cornelis Croesinck also changed the image that accompanies the text, thus altering the reader’s experience even more profoundly: instead of Mary and John praying beneath the cross, the text is now illustrated by an elaborate image of the Crucifixion showing Christ between the two robbers and beneath the cross his tormentors and friends, of course still including Mary and John, but reflecting the more diverse perspective of the prayer (fig. 17).

The Master of Cornelis Croesinck also found a different solution for illustrating the prayers in a more efficient way. Each day, before the first prayer of the cycle, he painted a full-page miniature in which he chose either to show the most important event (as was the case with the Crucifixion on Saturday) or to combine several events in a single image, by dividing the miniature into several compartments (fig. 18) or, if the narrative sequence in the prayers allowed for such a treatment, by placing the events within a landscape, sometimes adding additional compartments in the border decoration and thus combining up to five “images” or episodes on one leaf (fig. 19). Images of subsequent prayers, which he was unable to fit onto the first leaf, were placed within or next to the initial at the start of the prayer, as was the case with the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 20). This layout is, of course, far removed from the image-and-text diptych in the printed books, creating an experience that was directed rather more toward the larger narrative. The size and layout of the images made them suitable as mnemonic devices and as meditative images that let the reader travel mentally through a number of events at a time—which is quite divergent from single devotional images functioning in close relation to the text of a prayer.

In her manuscript, Cornelia van Wulfschkercke maintained the alternation of text and image that characterized the printed editions, although she placed the text on the verso and the image on the recto of each leaf. The prayer cycle, however, is not ordered according to the days of the week and, as noted above, the prayers are abridged. In making the manuscript Cornelia was most likely trying to satisfy her own devotional requirements, and it appears that the existing image-and-text diptychs did not always fulfill her needs. The inclusion of the Adoration of the Magi for example, was apparently not sufficient to support her devotion. The fact that Christ sent an angel to inform the shepherds about his birth, only briefly mentioned in the printed editions, is in her manuscript turned into a separate prayer accompanied by a miniature of the shepherds rejoicing upon seeing the angel in the sky (fig. 21). The text of the prayer, however, does not provide a clear model for the soul to emulate—the votary simply prays for protection against deadly sins, which eventually leads to eternal joy. Apart from illustrating the joy of the shepherds, the additional image might have served as a model for the joy one should feel when rejoicing in Christ’s birth, but the text does not offer any direct clues.

Instead of illustrating the prayer cycle by hand—whether with drawings or painted miniatures—another option for creating an illustrated prayer cycle in late medieval book production was the use of engravings, usually printed on loose leaves and pasted into manuscripts. A manuscript kept in Vienna starts with the last (seventh) prayer to the Trinity (which might suggest that part of the manuscript is missing) and contains the prayer cycle on the history of salvation illustrated with engravings by the Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ms. Series Nova 12909). The engravings were, however, not pasted in as loose leaves but printed on bifolia in two gatherings and arranged into a booklet.81 According to Ursula Weekes one of the innovative commercial strategies of engravers was to sell such ready-made booklets to which texts could be added later, pointing to the Vienna manuscript as the example par excellence.82 Image thus seems to have preceded text, although in this instance the text had previously been combined with a related series of woodcuts in the printed editions. A relation between the engravings by the Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs and the woodcuts for the Devote ghetiden has been briefly noted by the art historian Fritz Oskar Schupisser and needs further study, especially now it has become clear that both series accompanied the same text in late medieval books (both printed books and manuscripts).83 The situation with regard to the complex of visual material transmitted together with the Devote ghetiden in print and manuscript (Leeu’s and Bellaert’s woodblocks, engravings by the Master of the Ten Thousand Martyrs, and drawings and miniatures, which in turn are [partly] based on printed material) is too intricate and intermeshed than to allow to point to a single origin of the compositions.

In the Vienna manuscript the engravings sometimes precede the text, appearing on the left-hand side of the opening (fols. 1–26v and 55v–79v), but in all other sections of the manuscript the texts precede the engravings, which are placed on the rectos of the leaves. The makers of this codex encountered the same problem as the Masters of Hugo Jansz van Woerden: most prayers did not fit on a single page and the versos of most of the engravings were consequently left entirely blank. In the sections where the engraving is placed on the left of the opening and thus precedes the prayer, the effect achieved was similar to the printed books. In the other sections, however, the reader had to read the principal part of the prayer without viewing the image. Placing the engravings at the end of the prayers gives the impression that they are additions, afterthoughts rather than integral parts of the meditative prayers.

Finally, it is important to note that two of the manuscripts do not contain any images at all.84 Apparently the images were deemed very useful but not indispensable for a fruitful use of the text. These manuscripts suggest that the pragmatics of prayer did not necessarily demand images. The use of “external” pictorial aids such as paintings or single-leaf woodcuts cannot, of course, be ruled out.

Conclusions

With the printed editions of the Devote ghetiden Gerard Leeu catered to the taste for devotional and meditative books geared toward private use by a lay readership. The text would have appealed to the growing urban community looking for a way to engage more deeply with spiritual growth. The relative success of this text shows that several decades before the Reformation people had already become accustomed to seeking printed material that would give direction to their religious practices. Pictorial material played an increasingly important role as books with many illustrations could now be produced more cheaply. In this sense the Devote ghetiden provide an indication that the printing press did indeed bring about new forms of religious reading and meditative practice: the incorporation of large quantities of pictorial material in printed books strengthened their visual appeal and reflect the turn toward more visualization in late medieval devotion.85

When this pictorial material—woodcuts—is studied in the context for which it was made initially (or even its reuse in combination with different texts, which would be the next step) we can understand its function in lay devotion more profoundly. Although Webber states as an obvious fact that prayer cycles such as the one that was part of the Devote ghetiden were created for use within religious communities, a more in-depth reading of the Devote ghetiden shows that this was not the case.86 Neither are there indications that this text was intended for female readers in particular—the consistent neutral gendering of the prayers is just one sign that points to a mixed readership.87 The Devote ghetiden represent new attitudes toward text-and-image devotions in the transitional period between manuscript and print, revealing insights about the larger complex dialogue between text and image in late medieval devotion.

Until recently, a book like the Devote ghetiden would have undoubtedly been connected to the reform movement known as Modern Devotion.88 Studies by Koen Goudriaan have shown, however, that the large production of vernacular works with a religious character, which were intended by early printers in the Low Countries to reach a wide audience, cannot be seen as a direct result of the Devotio Moderna.89 Instead, members of the Franciscan Observance are now seen as important initiators of early publications of vernacular devotional literature. Their share in the entire production is however also limited—only about 150 out of almost 1,300 editions.90 The Devote ghetiden is a good example of one of the many texts whose origin is not absolutely clear but which did meet the demand for suitable spiritual literature among the laity and in turn influenced lay devotion at the end of the Middle Ages. The circles in which the edition came into being—the author-compiler was a well-educated priest, possibly with connections to chambers of rhetoric; the commercial printer collaborated with other creative professionals (e.g. woodcutters)—form the context in which a large part of ‘pre-Reformation’ printed devotional literature must have originated. As the Church did not have a specific strategy with regard to printing in the Low Countries, it was these kinds of creative collaborative communities that discovered a gap in the market. In meeting the demand they freely exploited a vast field of possibilities and by no means restricted themselves to reproducing texts and genres already established in manuscript circulation.91

Lay spirituality and the responsibility late-medieval people felt for the wellbeing of their souls proved commercially interesting and formed an important way for creative professionals such as printers to exercise, innovate, and develop their trade. In Antwerp, professionals of the “creative industry” avant la lettre, were united in the guild of St. Luke.92 Gerard Leeu was the first printer to become a member of the guild. Printers, painters and poets collaborated in administrative functions and creative manifestations such as city festivals.93 Their productions also dovetailed with the consumption of text and image: mainstream texts such as the Devote ghetiden could be purchased alongside paintings and sculpture in or close to the art market at Our Lady’s Pandt. It was this collaborative community and market to which Leeu brought the Devote ghetiden in 1484/5. His innovative product—combining user-friendly texts with a large quantity of images—influenced other media such as manuscripts. Jeffrey Hamburger already noted that prints had an impact on the illustration of prayer books, especially in the Lower Rhine region, with reference to two prayer books with illustrations reminiscent of prints, but not directly dependent on them.94 The case of the Devote ghetiden provides further confirmation of the influence of printing on manuscript illumination, which resulted in handwritten codices with expansive pictorial narratives that until the late fifteenth century were relatively rare in manuscripts.95

In contrast to the communis opinio, which generally regards printed books as plain, monochrome products compared to the colorful personal manuscripts of the late medieval period, and in which printers are generally thought to imitate manuscript production,96 it seems that in the case of the Devote ghetiden the influence was reversed. Printed books inspired luxurious manuscripts with unprecedented numbers of (full leaf) miniatures, making manuscript illumination ever richer. A dazzlingly colorful and sumptuous manuscript such as the London codex containing the Devote ghetiden would have been at least partly inspired by the products of the early printing press, and it cannot be ruled out that they influenced other media and visual art (paintings) as well.97

Clearly, books such as the Devote ghetiden influenced other forms of artistic expression, accelerating iconographic developments in a variety of media, but they also informed the minds of readers and viewers, influencing their perception and appreciation of art.98 They can help us understand the knowledge of the faith that laypeople had at their disposal and the way they related to, reacted to, and explained pictorial images—whether encountered in a book, a print, or a painting. The unique selling point of the Devote ghetiden lay in its ability to provide devotional guidance for busy laypeople, who did not have the time nor the strength to pray the hours contained in a traditional book of hours. This shows at once the flexibility of late medieval piety and its commercial potential.