Archival and Manuscript Sources

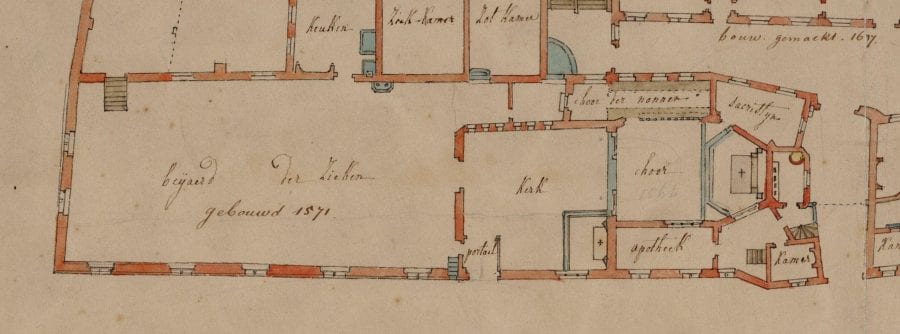

Mechelen, Archief van het Aartsbisdom Mechelen-Brussel (AAM). Gasthuiszusters Mechelen 1, Statuten en ordonnanties, 1509. Statutes of reform, May 17, 1509. “Onze Lieve Vrouwgasthuis te Mechelen.” Manuscript. Historical account of the history of Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis composed by unidentified sisters, early twentieth century.

Mechelen, Stadsarchief (SAM). Archief van de COO. OCMW 3094. Testament of Jacob Van den Putte and Margaretha Svos, April 9, 1524. OCMW 3102. Testament of Jacob Van den Putte and Margaretha Svos, April 9, 1527 [1526]. OCMW 8763. Rights of Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis to property left by the deceased, October 19, 1520. OCMW 8797-8805. Rekeningen (financial registers), Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis, 1494–1554 (registers for 1527–32 are absent). OCMW 8775. Pitantieboek, Heilige Geesttafel van Hanswijk, 1523.

The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 71 G 53 (prayer book).

Heverlee (Leuven), Abdij van Park, Ms. 18 (prayer book).

Printed Sources

Anderson, Christy, Anne Dunlop, and Pamela H. Smith, eds. The Matter of Art: Materials, Practices, Cultural Logics, c. 1250–1750. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Appuhn, Horst. “Die Paradiesgärtlein des Klosters Ebstorf.” Lüneburger Blätter 19–20 (1968–69): 27–39.

Areford, David S. The Art of Empathy: The Mother of Sorrows in Northern Renaissance Art and Devotion. London and Jacksonville, Fla.: GILES for the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens, 2013.

Augustine, The Trinity (De Trinitate). Translated with introduction and notes by Edmund Hill. Brooklyn, N.Y.: New City Press, 1991.

Baert, Barbara. “Echoes of Liminal Spaces. Revisiting the Late Mediaeval ‘Enclosed Gardens’ of the Low Countries (A Hermeneutical Contribution to Chthonic Artistic Expression).” Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (2012): 9–46.

_______. Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries: Contributions to Gender and Artistic Expression. Leuven: Peeters, 2016.

_______. “‘An Odour. A Taste. A Touch. Impossible to Describe’: Noli Me Tangere and the Senses.” In Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe, edited by Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler, 111–51. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Baert, Barbara, with an epilogue by Lise De Greff. “The Glorified Body.” In Backlit Heaven: Power and Devotion in the Archdiocese of Mechelen, 130–52. Tielt: Lannoo, 2009.

Bagnoli, Martina, et al., eds. Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Exh. cat. Cleveland Museum of Art; Baltimore: Walters Art Museum; London: The British Museum/New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Barasch, Moche. Blindness: The Story of a Mental Image in Western Thought. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Boccaccio, Giovanni. Famous Women. Translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Brodman, James. Charity and Religion in Medieval Europe. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2009.

Brown, Andrew. “Civic Charity.” In Civic Ceremony and Religion in Medieval Bruges c. 1300–1520, 195–221. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books, 2011.

Crab, Jan. Het Brabants Beeldsnijcentrum Leuven. Leuven: Stedelijk Museum Leuven, 1977.

_______. Het laatgotische beeldsnijcentrum Leuven: Tentoonstelling, Leuven, Stedelijk Museum, 6 oktober–2 december 1979. Leuven: Stedelijk Museum, 1979.

Cunningham, Andrew, and Ole Peter Grell, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700. London: Routledge, 1997.

Decker, John. “‘Practical Devotion’: Apotropaism and the Protection of the Soul.” In The Authority of the Word: Reflecting on Image and Text in Northern Europe, 1400–1700, edited by Celeste Brusati, Karl A. E. Enenkel, and Walter S. Melion, 357–84. Boston: Brill, 2009.

Decker, John. The Technology of Salvation and the Art of Geertgen tot Sint Jans. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2009.

Dony, Paul. “Les ‘Jardins Clos.’” Ecclesia 98 (May 1957): 119–26.

Eichberger, Dagmar. Leben mit Kunst, Wirken durch Kunst: Sammelwesen und Hofkunst unter Margarete von Österreich, Regentin der Niederlande. Turnhout: Brepols, 2002.

800 jaar Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis: Uit het erfgoed van de Mechelse gasthuiszusters en het OCMW. Exh, cat. Mechelen: Stedelijke Musea, 1998.

Eyler, Joshua R., ed. Disability in the Middle Ages: Reconsiderations and Reverberations. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2010.

Falkenburg, Reindert M. The Fruit of Devotion: Mysticism and the Imagery of Love in Flemish Paintings of the Virgin and Child, 1450–1550. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 1994. Falkenburg, R. L., W. S. Melion, T. M. Richardson, eds. Image and Imagination of the Religious Self in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007.

Falque, Ingrid. “Portraits de dévots, pratiques religieuses et expérience spirituelle dans la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas (1400–1550).” PhD diss., University of Liège, 2009. Forthcoming as Devotional Portraiture and Spiritual Experience in Early Netherlandish Painting. Leiden: Brill.

Franklin, Margaret. Boccaccio’s Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2006.

Freeman, Charles. Holy Bones, Holy Dust: How Relics Shaped the History of Medieval Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Godenne, W. “Préliminaires à l’inventaire général des statuettes d’origine malinoise, présumées des 15e et 16e siècles.” Handelingen van de Koninklijke Kring voor Oudheidkunde, Letteren en Kunst van Mechelen 61 (1957): 47–127.

Green, Monica. “Bodies, Gender, Health, Disease: Recent Work on Medieval Women’s Medicine.” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 4 (2005): 1-46.

________. “Gendering the History of Women’s Healthcare.” Gender and History 20 (2008): 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0424.2008.00534.x

Hahn, Cynthia. Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400–circa 1204. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

Hamburger, Jeffrey F. Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

_________. The Visual and the Visionary: Art and Female Spirituality in Late Medieval Germany. New York: Zone Books/Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1998.

Hamburger, Jeffrey F., Petra Marx, and Susan Marti. “The Time of the Orders, 1200–1500: An Introduction.” In Crown and Veil: Female Monasticism from the Fifth to the Fifteenth Centuries, edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Susan Marti, 41–75. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Hellerstedt, Kahren Jones. “The Blind Man and His Guide in Early Netherlandish Painting.” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 13 (1983): 163–81.

Hobgood, Allison P., and David Houston Wood, eds. Recovering Disability in Early Modern England. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2013.

Irigaray, Luce. “La voie du féminin.” In Hooglied: De beeldwereld van religieuze vrouwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, vanaf de 13de eeuw/Le jardin clos de l’ame: L’imaginaire des religieuses dans les Pays-Bas du Sud depuis le 13e siècle, edited by Paul Vandenbroeck, 155–65. Exh. cat. Brussels: Paleis voor Schonen Kunsten/Martial et Snoeck, 1994.

Jacobs, Lynn F. Early Netherlandish Carved Altarpieces, 1380–1550: Medieval Tastes and Mass Marketing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

James, Liz. “Hysterical (Hi)stories of Art.” Oxford Art Journal 18, no. 1 (1995): 143–47.

Jansen, A. “Losse nota’s over de merktekens op de Mechelse beeldjes (15e–16e eeuwen).” Koninklijke Kring voor Oudheldkunde Letteren en Kunst van Mechelen 66 (1962): 148–56.

Karcioglu, Zeynel A. “Ocular Pathology in The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind and Other Paintings by Pieter Bruegel.” Survey of Ophthamology 47, no. 1 (Jan.–Feb. 2002): 55–62.

“Keuze uit de aanwinsten. I: Paneeltje met Maria Immaculata.” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 56, no. 4 (2008): 474–75.

Kirkland-Ives, Mitzi. In the Footsteps of Christ: Hans Memling’s Passion Narratives and the Devotional Imagination in the Early Modern Netherlands. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013.

Kok, J. P. Filedt. “De zeven werken van barmhartigheid, Meester van Alkmaar, 1504.” Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.9048).

Kristeva, Julia. “Le Bonheur des beguines.” In Hooglied: De beeldwereld van religieuze vrouwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, vanaf de 13de eeuw/Le jardin clos de l’ame: L’imaginaire des religieuses dans les Pays-Bas du Sud depuis le 13e siècle, edited by Paul Vandenbroeck, 167–77. Exh. cat. Brussels: Paleis voor Schonen Kunsten/Martial et Snoeck, 1994.

Krohm, Harmut. “Reliquienpräsentation und Blumengarten: kunstgeschichtliche Bemerkungen zu den Schreinen in Kloster Bentlage.” Westfalen 77 (1999): 23–52. Kromm, Jane. “The Early Modern Lottery in the Netherlands: Charity as Festival and Parody.” In Parody and Festivity in Early Modern Art: Essays on Comedy as Social Vision, edited by David R. Smith, 51–62. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate 2012.

LeZotte, Annette. “Cradling Power: Female Devotions and Early Netherlandish Jésueaux.” In Push Me, Pull You: Physical and Spatial Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art, edited by Sarah Blick and Laura D. Gelfand, 59–84. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

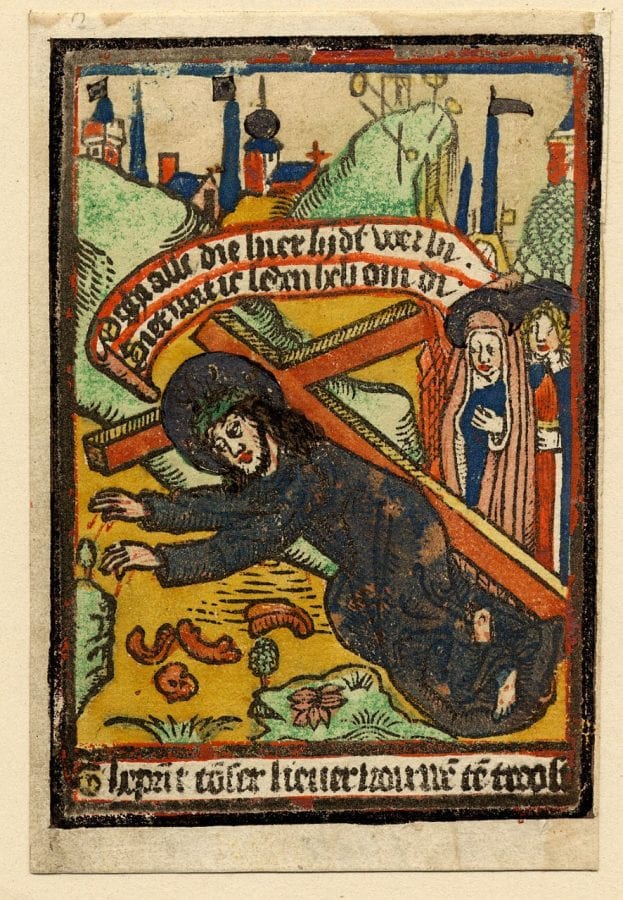

Ludolph of Saxony. Tboeck vanden leven ons heeren Jesu Christi (The book of the life of our Lord Jesus Christ). Zwolle (?): Peter van Os, 1495.

Marcus, Felix. “Die Mechelener ‘Jardin Clos.’” In Der Cicerone: Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers and Sammlers, edited by Georg Biermann, 98–101. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1913.

Marinus, Albert. “Le Jardin Clos.” In Le Folklore Belge, vol. 3, 234–57. Brussels: Les éditions historiques/Turnhout: Brepols, 1937.

Matter, E. Ann. The Voice of My Beloved: The Song of Songs in Western Medieval Christianity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

McAvoy, Liz Herbert. “The Medieval Hortus conclusus: Revisiting the Pleasure Garden.” Medieval Feminist Forum 50, no. 1 (2014): 5–10.

Mellinkoff, Ruth. Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages. 2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Metzler, Irina. Disability in Medieval Europe: Thinking about Physical Impairment during the High Middle Ages, c. 1100-1400. New York: Routledge, 2006.

________. A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Naemlyst der Zusters van O.-L.-V. Gasthuis, der Zusters van O.-L.-V. Gasthuis, sedert hare Stichting, binnen Mechelen. Mechelen: H. Dierickx-Beke, 1862.

Nuechterlein, Jeanne. “Hans Memling’s St. Ursula Shrine: The Subject as Object of Pilgrimage.” In Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe, 51–75. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Obbema, P. F. J., et al., Boccaccio in Nederland: Tentoonstelling van handschriften en gedrukte werken uit het bezit van Nederlandse bibliotheken ter herdenking van het zeshonderdste sterfjaar van Boccaccio (1313–1375). Leiden: Academisch Historisch Museum, 1975.

Ockeley, Jaak. De gasthuiszusters en hun ziekenzorg in het aarsbisdom Mechelen in de 17de en de 18de eeuw: Bijdrage tot de studie van de actieve vrouwelijke kloostercongregaties. Brussels: Archives et bibliothèques de Belgique, 1992.

_______. “Het Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis te Mechelen van de stichting tot het begin van de negentiende eeuw.” In 800 jaar Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis: Uit het erfgoed van de Mechelse gasthuiszusters en het OCMW, 7–23. Mechelen: Stedelijke Musea, 1998.

Os, Henk W. van. The Way to Heaven: Relic Veneration in the Middle Ages. Baarn: de Prom, 2000.

Os, Henk W. van, Jan Piet Filedt Kok, Ger Luijten, and Frits Scholten. Netherlandish Art in the Rijksmuseum: 1400–1600. Zwolle: Waanders, 2000.

Palazzo, Éric. L’ invention chrétienne des cinq sens dans la liturgie et l’art au Moyen âge. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2014.

Parshall, Peter, ed. The Woodcut in Fifteenth-Century Europe. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2009.

Pearson, Andrea. Envisioning Gender in Burgundian Devotional Art, 1350–1530: Experience, Authority, Resistance. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2005.

_________. “Visuality, Morality, and Same-Sex Desire: The Infants Christ and St. John the Baptist in Early Netherlandish Art.” Art History 38, no. 3 (2015): 434–61.

Pelzer, Birgit. “Reliquats.” In Hooglied: De beeldwereld van religieuze vrouwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, vanaf de 13de eeuw/Le jardin clos de l’ame: L’imaginaire des religieuses dans les Pays-Bas du Sud depuis le 13e siècle, edited by Paul Vandenbroeck, 179–203. Exh. cat. Brussels: Paleis voor Schonen Kunsten/Martial et Snoeck, 1994.

Poupeye, Camille. “Les jardins clos et leurs rapports avec la sculpture Malinoise.” Bulletin du Cercle archéologique, littéraire et artistique de Malines 22 (1912): 50–114.

Rankin, Alisha. “Women in Science and Medicine, 1400–1800.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe, edited by Allyson M. Poska, Jane Couchman, and Katherine A. McIver, 407–21. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2013.

Rawcliffe, Carole. “‘Delectable Sightes and Fragrant Smelles’: Gardens and Health in Late Medieval and Early Modern England.” Garden History 37 (2008): 3–21.

Réau, Louis. Iconographie de l’Art Chrétien. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1958.

Ritchey, Sara. Holy Matter: Changing Perceptions of the Material World in Late Medieval Christianity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9780801452536.001.0001

Robinson, James, and Lloyd de Beer, eds., with Anna Harnden. Matter of Faith: An Interdisciplinary Study of Relics and Relic Veneration in the Medieval Period. London: The British Museum, 2014.

Roo, R. de. “Mechelse Beeldhouwkunst.” In Aspekten van de laatgotiek in Brabant: Tentoonstelling ingericht door de Intercommunale Interleuven ter gelegenheid van haar vijfjarig bestaan, 420–62. Leuven: Stedelijk Museum, 1971.

Rothstein, Bret. “Gender and the Configuration of Early Netherlandish Devotional Skill.” In Women and Portraits in Early Modern Europe: Gender, Agency, Identity, edited by Andrea Pearson, 15–34. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2008.

Rothstein, Bret. Sight and Spirituality in Early Netherlandish Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Row-Heyveld, Lindsey. “‘The lying’st knave in Christendom’: The Development of Disability in the False Miracle of St. Alban’s.” Disability Studies Quarterly 29, no. 4 (Fall 2009): n.p. (http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/994/1178).

Rudy, Kathryn M. “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer.” JHNA: Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2, nos. 1–2 (2010): 1–26 https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2010.2.1.1

_______. “How to Prepare the Bedroom for the Bridegroom.” In Frauen-Kloster-Kunst: Neue Forschungen zur Kulturgeschichte des Mittelalters, edited by Carola Jaeggi, Hedwig Roeckelein, and Jeffrey F. Hamburger, 369–75. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007.

________. Virtual Pilgrimages in the Convent: Imagining Jerusalem in the Late Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.DM-EB.5.108575

Safley, Thomas, ed. The Reformation of Charity: The Secular and the Religious in Early Modern Poor Relief. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Sanger, Alice E., and Siv Tove Kulbrandstad Walker, eds. Sense and the Senses in Early Modern Art and Cultural Practice. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2012.

Scott, Anne M. “Experiences of Charity: Complex Motivations in the Charitable Endeavour, c. 1100–c. 1650.” In Experiences of Charity, 1250–1650, edited by Anne M. Scott, 1–14. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2015.

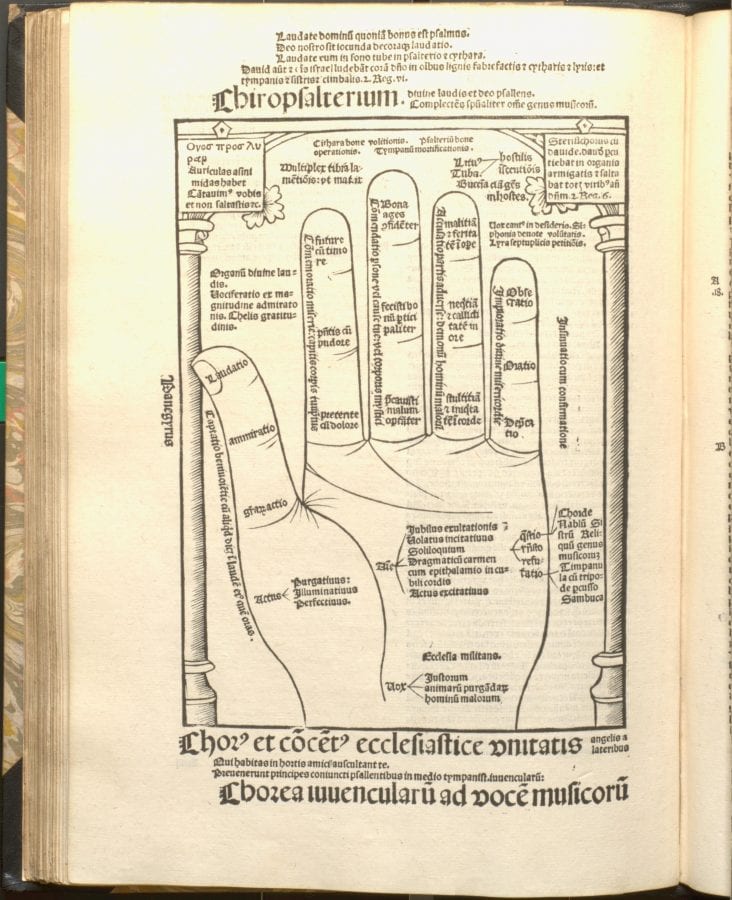

Sherman, Claire Richter. Writing on Hands: Memory and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe. Exh. cat. Carlisle, Penn.: Dickinson College, Trout Gallery; Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library/Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

Silver, Larry, and Henry Luttikhuizen. “The Quality of Mercy: Representations of Charity in Early Netherlandish Art.” Studies in Iconography 29 (2008): 216–48.

Strocchia, Sharon T. “Introduction.” In “Women and Healthcare in Early Modern Europe.” Special issue. Renaissance Studies 28, no. 4 (Sept. 2014): 496–514.

Swanson, R. N. Religion and Devotion in Europe, c. 1215–c. 1515. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Van Engen, John. Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life: The Devotio Moderna and the World of the Later Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Van Ravensteyn, Frieda. “Het hospitaal van Geel van zijn ontstaan tot 1552.” In 450 jaar Gasthuiszusters Augustinessen van Geel, edited by Frieda Van Ravensteyn, Michel De Bont, and Jaak Segers, 8–21 and 188. Geel: St.-Dimpna- en Gasthuismuseum, 2002.

Vance, Eugene. “Seeing God: Augustine, Sensation, and the Mind’s Eye.” In Rethinking the Medieval Senses: Heritage/Fascinations/Frames, edited by Stephen G. Nichols, Andreas Kablitz, and Alison Calhoun, 13–29. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Vandamme, Erik. “Het ‘Besloten Hofje’ in het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten te Antwerpen: Bijdrage tot de studie van de kunstnijverheid in de provinciale Zuidnederlandse centra omstreeks 1500.” In Archivum Artis Lovaniense: Bijdragen tot de Geschiedenis van de Kunst der Nederlanden; Opgedragen aan Prof. Em. Dr. J. K. Steppe, edited by Maurits Smeyers, 143–49. Leuven: Peeters, 1981.

Vandenberghe, Stéphane. “Besloten Hofjes.” In 800 jaar Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis: Uit het erfgoed van de Mechelse gasthuiszusters en het OCMW, 49–57. Exh. cat. Mechelen: Stedelijke Musea, 1998.

Vandenbroeck, Paul. “Tu m’effleures.” In Hooglied: De beeldwereld van religieuze vrouwen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, vanaf de 13de eeuw/Le jardin clos de l’ame: L’imaginaire des religieuses dans les Pays-Bas du Sud depuis le 13e siècle, edited by Paul Vandenbroeck, 13–153. Exh. cat. Brussels: Paleis voor Schonen Kunsten/Martial et Snoeck, 1994.

Vandermeersch, Joke, and Lieve Watteeuw. “De conservering van de 16de-eeuwse Mechelse Besloten Hofjes; Een interdisciplinaire aanpak voor historische mixed media.” In Postprints 8ste BRK-APROA/Onroerend Erfgoed Colloquium: Innovatie in de conservatie-restauratie. Brussels, November 12–13, 2015.

Vives, Juan Luis. De subventione pauperum sive de humanis necessitatibus, Libri II: Introduction, Critical Edition, Translation and Notes. Edited by Charles Fantazzi and Constantinus Matheeussen, with the assistance of J. de Landtsheer. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Vives, Juan Luis. On Assistance to the Poor. Translated with introduction and commentary by Alice Tobriner. Toronto: University of Toronto Press in association with the Renaissance Society of America, 1999.

Vives, Juan Luis. The Origins of Modern Welfare: Juan Luis Vives, De Subventione Pauperum, and City of Ypres, Forma Subventionis Pauperum. Translated with notes and commentary by Paul Spicker. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2010.

Voragine, Jacobus de. The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Weale, W. H. James. Catalogue des objets d’art religieux du moyen âge, de la renaissance et des temps modernes: Exposés à l’Hotel Liedekerke à Malines, Septembre 1864. Brussels: Charles Lelong, 1864.

Wheatley, Edward. Stumbling Blocks before the Blind: Medieval Constructs of Disability. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.915892

Wuyts, Ben. Over Narren, Kreupelen, Doven en Blinden: Leven met een Handicap, van de Oudheid tot Nu. Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2005.

Yoshikawa, Naoë Kukita. “The Virgin in the Hortus conclusus: Healing the Body and Healing the Soul.” Medieval Feminist Forum 50, no. 1 (2014): 11–32.