The maps of Brazil published during the tenure of the Dutch Republic’s possession of the territory (1630–54) share common features that demonstrate how existing conventions in rhetoric and iconography were used by publishers to convey Dutch ownership. In the maps, the land was visually controlled by ground plans distinguishing cultivated and occupied lands from uncultivated, unoccupied territory, and the texts drew upon contemporary legal and engineering theories developed from antique precedents. Texts and images of Pernambuco published by Claes Jansz Visscher and by Joan Blaeu served as important means for defining the Dutch nation by reinforcing Dutch conceptions of property rights in prints of territories abroad.

The maps of Brazil published by Claes Jansz Visscher and Joan Blaeu (figs. 1-4) present a synthesis of Dutch military, commercial, and colonial success for the West India Company (WIC). Visual cues evinced legal possession and economic stability. They defined cities and open land available for cultivation, waterways for transport, defense, and power, and stands of brazilwood and fields of sugar cane being made into commodities by the tools of human industry. These prints corroborated Dutch claims to the land and its resources by visually engaging with contemporary ideas about law and development. These views of land and law were inextricable from each other, and from the Dutch concept of civilization. The maps and associated views emphasized the ancient Roman law of possession by depicting land as being controlled by the technologies employed for government and commerce. The compositional familiarity of these maps helped readers to visualize the domestication of land abroad by means similar to those which were being used to claim territory for the Dutch in Europe.

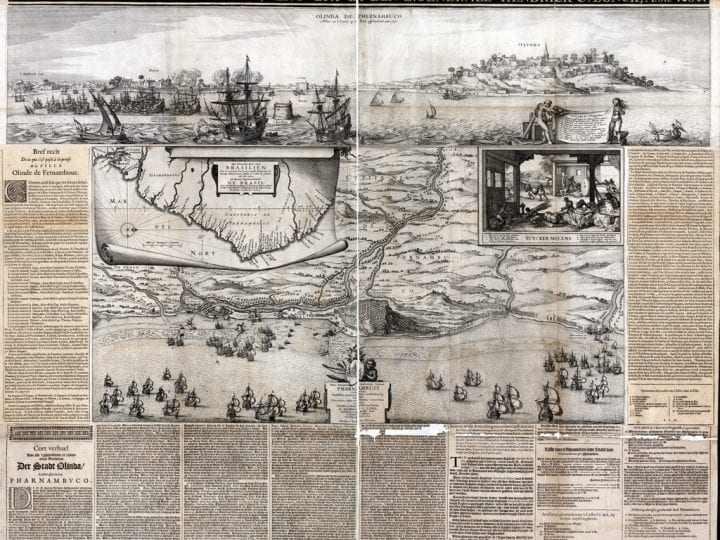

The WIC provided both Visscher and Blaeu with hand-written manuscript sources for their projects. A news map, Visscher’s 1630 map of Pernambuco (fig. 1) consists of four conjoined sheets. At over one meter square, it was meant to hang proudly on the walls of Dutch burghers’ townhouses and offices. The folio maps and views of Dutch Brazil published by Blaeu (figs. 2-4), on the other hand, were intended for a wealthy readership. Published in Caspar Barlaeus’s Rerum per octennium in Brasilia in 1647, they illustrated the glorified history of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen’s governorship.1 Blaeu also sold a multisheet wall map based on the prints bound together in Barlaeus’s folio.) Not many maps of Brazil were published during the territory’s possession by the Dutch from 1630 to 1654, but these few did provide investors and readers interested in the New World with two formats for learning about Dutch conquests in Brazil.2 Because of the militaristic nature of the initial forays into Brazil, the manuscript maps that WIC captains and surveyors brought back with them to the Netherlands remained privy to those select few with access to WIC intelligence. Visscher, however, was specifically given the rights to publish the 1630 map. In fact, he had already collaborated with the WIC’s cartographer Hessel Gerritsz on earlier maps: one depicting the conquest of Bahía in 1624 and another detailing Piet Heyn’s capture of the Spanish silver fleet off Cuba in 1628.3

Visscher was instrumental in developing these news maps into sheets that were at once pictorial and informational. Early in his career, he established a niche in the production of printed landscapes of the Dutch countryside and maps of Dutch victories against Spain.4 It was therefore logical that the WIC would authorize Visscher to create a map of Pernambuco detailing the events of the 1630 conquest, images along with texts.5 As for Joan Blaeu, he followed his father Willem’s inroads with the merchant trading companies, becoming another publisher who frequently issued maps for the WIC. His access to the WIC’s collection of manuscript maps provided much of the data for the atlases he published, many of which were geared to the educated merchant and regent class.6

Visscher and Blaeu’s respective prints suggested to investors the bounty in Brazil and the WIC’s control of it. Both publishers presented Brazil using conventions in rhetoric and iconography that helped assert Dutch possession and confirm Dutch control over natural resources.7 These images echoed important legal ideas about possession that were articulated in contemporary texts. In the first quarter of the seventeenth century, the influential Dutch legal theorist Hugo Grotius described his ideas about property and sovereignty based on natural law. Grotius’s ideas will be explored in greater detail later on, but for now, it is important to observe that, for Grotius, natural law originated in self-preservation. Man developed technology to cultivate land and provide for himself; subsequently individuals organized their respective contributions to the community (civitas) by means of government and commerce. Natural law substantiated the Aristotelian ideal of the city as the apex of civilization.8

Maps of Dutch territories visually share the language of texts that emphasized the built environment, the cultivation of land, and the strategic use of waterways. Taken together the combination of city profile, topographical view, and vignette depicted the cityas developed, that is, physically built by and of the institutions that regulated society and its products, and distinct from the uncultivated and open areas often described as deserted (terrarum deserta) or belonging to no one (res nullius). These pictorial elements reinforced the WIC’s possession of Pernambuco and its natural resources. The maps thereby presented Brazil as a secure and stable colony, a place worthy of investment. In actuality, the WIC’s control of Pernambuco was anything but certain. As we will see, these maps presented a message that belied an increasingly uncertain situation in Brazil.

Visscher’s WIC-Authorized Map of Pernambuco

The history of Dutch presence in Brazil began in the first week of September in 1624. It had taken almost three years for the fledgling WIC to obtain sufficient capital to send a fleet to South America to challenge Habsburg hegemony in the Atlantic. The WIC directors agreed that the conquest of Bahía should be their goal, since it was already an economic and operational center for the Portuguese. Admiral Jacob Willekens and Vice-Admiral Piet Heyn led the Dutch fleet to the Bay of Salvador de Bahía in May of 1624 and defeated the Portuguese. This first Dutch victory in the Atlantic provided a much-needed boost for the fledgling WIC and fueled the growth of Dutch unity and nationalism during a period of religious and political divisiveness at home. However, because they underestimated the speed and power behind the Iberian response, the Dutch lost Bahía in the spring of 1625, and it reverted to Portuguese control.9

The WIC continued to pursue control of northeast Brazil, and in 1630 Admiral Hendrick Lonck and his fleet overpowered Olinda and Recife. Visscher was again chosen by the WIC to publish the WIC’s successful military activity (fig. 1). The map includes text in French and Dutch describing the event, a coastal outline of the area, and ground plans of Recife and Olinda. The text proclaims that all this was drawn from life: “aldus na ‘t Leven op de Rede afgheteyckent anno 1630.”The island of Antonio Vaz, Recife (called Povo on the map), and Olinda are depicted in profile. Nude Native Americans hold a cartouche identifying the important locations at Recife, including the location of the yard where ships were built and repaired (1 on the key), Recife’s church (5), the sugar warehouses (6), here set on fire by the fleeing Portuguese (called “Spanish” in the key), an earthen wall with bulwarks (7), and a new wooden bridge (13). A fleet of Dutch ships commands the harbor. A vignette to the right depicts African slaves pressing sugar cane. In the central topographical view, the conquered Portuguese town of Olinda is shown in plan, surrounded by rivers that converge in the harbor between Recife and Olinda. A cartellino on the left shows the northeast coastline of Brazil.

In this map, Visscher repurposed the visual language already used for views and plans of European cities, though now for Recife and Olinda. Visscher combined profile, topographical view, and vignette, thereby “domesticating” these towns by incorporating them into the schema familiar from maps and views of established European “nations.”10 Similar maps had been published in the Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1575), and Dutch publishers used the format for maps of Dutch cities published throughout the Eighty-Years War. The proliferation of city profiles and plans published in the seventeenth century reinforced a sense of group identity that was both provincial and nationalistic.11 Here, the profile view emphasizes those buildings that identify Recife as a developed city: churches, warehouses, homes, and protective wall, each clarified by the key. That the buildings were constructed by the Portuguese before the Dutch conquest was irrelevant, the goal was to show Recife as a cultivated and organized community. Significantly however, Visscher included the destruction of the warehouses by the Portuguese. This act indicated Portuguese abandonment, and therefore, the availability of the warehouses for Dutch possession. The Dutch ships in the harbor command the port and rivers, while the vast expanse of forest extends beyond the edges of the cities.

In contrast to the details of the built city and its commercial activity, the center area presents a general topographical view of Pernambuco. The broad expanse dotted by trees signifies open countryside, an uncultivated area rich in resources waiting to be developed by human industry. The cities, defined in plan and profile, provide a visual juxtaposition of the built, organized urban environment to the open land. Linking the two are the rivers–waterways used both for transport of goods and defense–along with the framed vignette showing sugar production.

Since before the founding of the WIC, sugar had been one of the principal commodities on which Dutch traders had set their sights. The lure of sugar in Brazil was a common theme in such printed publications from the 1620s as Nicolaas van Wassenaar’s chronicles and the small Reyse-boeck van het Rijcke Brasilien . . ., published in Dordrecht in 1624. The sugar mill in Visscher’s inset is similar to the rendering of a mill pictured in the 1624 Reyse-boeck.12 Visscher enclosed the process of sugar production within a square frame that serves to separate this industry from uncultivated land at the left. Within the frame, African slaves demonstrate each part of the process of sugar production, which is also described in the key below. In the left foreground, two slaves harvest cane, to be pressed by the slaves at the mill in the background. In the right foreground, three slaves boil the juice and separate the distilled syrup from the pulpy by-product (dram). Sugar, as a product of cultivated land, is shown here being processed and made into a refined commodity by the mechanisms and labor of man and machine. This product, in turn, is controlled by the Dutch. The frame creates a legible, defined space that functions as a visual metaphor for Dutch control of the sugar industry. The vignette depicts the refining of sugar for consumption, while the river visually links the commodity harvested from the interior to the harbor below. The ships in the harbor — in both the topographical and profile view — further underscore the fact that the WIC controls whatever goods arrive at or leave the Brazilian coast.

Organizing Polities, Places, and Pictures

Maps helped to define both the territory of the Dutch Republic as well as the territories it claimed abroad. The symbolic system that contrasted defined and developed cities with open and undeveloped areas underscored the Republic’s status as a global, commercial, and civilized nation during a crucial period of national identity formation. The span of time in which the Brazil maps were published coincided with a period critical to the recognition and legitimization of both the Dutch Republic and the WIC. In 1648, Spain recognized the Dutch Republic’s sovereignty at the Peace of Westphalia, ending the Eighty-Years War, although not all of the provinces were eager to sign on.13 In 1647, after two years of deliberation, the WIC’s charter was renewed.14 The initial charter granted to the WIC by the States General in 1621 integrated the shared militaristic and economic goals of the government and the company. It gave the WIC and its officials the power to make war and peace, to enter into trading contracts, and to develop colonies.15 Both Visscher and Blaeu capitalized on the demand for nationalistic propaganda in this context.The printed maps of Dutch-controlled Brazil formed part of a confidence-building and unifying use of the print media. They also served as sources of knowledge about Dutch conquest overseas and thus contributed to and reinforced conceptions of an “imagined” Dutch community.16

Printed maps reflected the land management policies of Holland and the WIC, and their respective pragmatic and moral philosophies about land, law, and civilization. Roman law, even if imprecisely applied, provided the model by which land could be organized as property and, as such, become a commodity.17 In Roman law, ownership (dominium) was indicated by occupation (occupatio) and control (factual possession — possessio) and therefore implied boundaries. The Dutch employed a commercially oriented and legalistic “period eye” to translate contemporary ideas from Roman-Dutch law and engineering into visual maps.18 The mapping of the Northern provinces and territories abroad in profile and plan visualized what was at the same time being codified into Dutch property law. Maps served many purposes: as legal documents, as navigational charts, and as sources of knowledge. Moreover, leaders — including WIC governors — often used maps as proof of possession. By using maps that visualized their control of the land, they were able to make a better claim to territory than competing nations.19

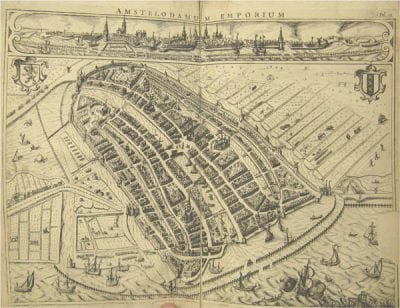

The profile view of Recife in Visscher’s map — with its church, warehouses, shops, and homes signifying the developed city (now conquered and controlled by the Dutch ships in the harbor) — resembles similar profile views in maps of Amsterdam. A good example can be found in Jodocus Hondius’s map of Amsterdam (fig. 5) in Johannes Pontanus’s Rerum et urbis Amstelodamensium historia (History and Activities of the City of Amsterdam; published in Latin in 1611 and in Dutch in 1614). This map likewise showcases the built city and its organization20 and, in the profile view stretching across the top, depicts the Amstel River penetrating Amsterdam’s dense clusters of shops and homes, separating the Old Church and the St. Antoniespoort weigh house (de Waagh) on the left from the New Church and town hall on the right. The buildings associated with institutions that serve the commonality — places of trade and taxation, government, and religion — punctuate the cityscape. Below, the ground plan is shown from a tilted, bird’s-eye view.

Such a view emphasized the organization of the city’s streets and canals as linkages that facilitated commerce. On the Amstel, boats are tied to wharves, ready to unload or load goods destined for the central shops. At the edge of the city, merchant ships bob in the harbor, just outside the palisade in the IJ. A gallows at the bottom right edge signifies the enforcement of law and regulations, such as the weights and duties measured at the weigh houses on the Dam and at St. Antoniespoort. The St. Antoniespoort gate and weigh house physically and visually bridges the division between the rectangular plots of land on the left and the shops in the city. Along with the gates, windmills project from the bastioned walls, marking the confluence of country and city created by industry. In the farmland, sluices that regulate the level of water clearly separate the land tracts. Livestock, farmers with scythes, and windmills identify the agricultural function of the land. Between the profile and the ground plan, two coats of arms show on the one hand Holland’s lion and on the other the three crosses of Saint Andrew, Amsterdam’s emblem.

In the same year as the map in Amstelodamensium historia, 1611, Visscher likewise associated Amsterdam with commerce organized by the institutions of civilization (fig. 6).21 In this allegorical profile view made up of sixteen sheets, he accompanied the view with texts that highlight the civilization and commercial rigor of Amsterdam. The cartouche in the top right includes a distich in Latin that reads:Religio, Merces, Artes, Politica, Themisque Amstelodami amplum dilatant nomen in Orbem (Piety, commerce, art and science, governance and legislation / spread the name of Amsterdam over the whole earth).The tools for those achievements are shown surrounding the cartouche (a globe, a pair of books, a painter’s palette, silver and glasswork, a music book, and the New Testament) (fig. 6a). In the picture below, Dutch citizens from North Holland and West Friesland haul a cornucopia of local fishes, meats, cheeses, and grains from the right side to meet the traders carrying their imported goods from abroad, who enter from the left. Below the panorama, Visscher included four scenes – the Dam, the bourse, the butchers’ hall, and fish market — accompanied by laudatory poems in Dutch. A key above marks forty-two buildings and churches — the institutions of the city — labeled on the map.

The texts surrounding the pictures, also in Dutch, elucidate the subjects advertised in the cartouche and provide detailed contemporary examples and comparisons to antiquity, specifically drawing the analogy between Amsterdam and Athens. Visscher’s texts articulate how Amsterdam’s foreign and domestic relations were organized and governed by wise and pious men like the ideal polis of Athens as described by Demosthenes, Plato, and Isocrates in his Areopagiticus.22 Tellingly, Visscher focused here on the institutions of the city, specifically its government, trade, and educational facilities, rather than on individual leaders. In addition, he felt compelled to mention some lacunae in his profile view: the texts include a history of the first inhabitants of Amsterdam, a description of the methods by which water was pumped away and how the town walls were built, all equally important feats. Indeed, Visscher included these subjects elsewhere in his printed oeuvre.23

The canals and streets in Visscher’s bird’s-eye view and the institutions of Amsterdam he features in the texts show the significance of engineering and organization in the city’s position as commercial center. It was no doubt because of its similarity to the Dutch capital that after the 1630 conquest, the WIC chose Recife as the headquarters of Dutch control; the city’s location and level of development maximized their superior maritime power, militarily and commercially. Recife and the adjacent island of Antonio Vaz, where Mauritsstad was built, lie barely seven feet above sea level, a geographical situation to which the Dutch engineers were accustomed. They proceeded to build dikes and canals to defend Recife against enemies and water and to assist transport to and from the interior. After the arrival of Johan Maurits, Mauritsstad was planned to amplify the twin cities’ role as commercial center.

In many ways, the plan for the city of Maurisstad followed military engineer Simon Stevin’s practical designs for military camps and cities. Stevin’s plans emphasized the use of waterways as natural defenses, and shows that he was adept at manipulating water for power via a system of sluices.24 Stevin’s city plan resembled the plans for the military camps he designed for Prince Maurits.25 He advocated that town plans be based on a grid for the purpose of defense and civic and commercial utility. In Stevin’s ideal city, the central feature was a plaza adjacent to the main church and town hall, with streets or canals serving as axes connecting it to the market exchange. It was extremely important that the waterways were controlled, both for defense and for levying tolls and duties on the import and export of goods.

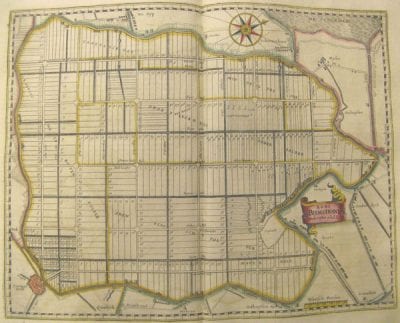

The plan for Mauritsstad (fig. 4), engraved after a drawing by WIC surveyor Cornelis Golijath from around 1643, demonstrates how Johan Maurits’s planner was influenced by Stevin in that he exploited the natural waterways to serve as extension of the axial roads, connecting the civic and commercial functions of the city. In Stevin’s “On the ordering of towns” (Van de ordeningh der Steden), [published posthumously by his son Hendrick in Materiae Politicae: Burgherlijcke Stoffen (Political Subjects: Civil Matters, 1649)] Stevin emphasized that

in newly discovered lands, where communities wish to settle . . . one looks for a fertile piece of land, situated at the mouth of a great navigable river, coming from distant countries, because such places can have two-way traffic, one from the sea the other inland. Further for the crops and crafts of the inhabitants of such vast countries to be distributed around the world, it all has to go through this river mouth. Likewise all overseas goods that such lands need, they must obtain them all through this river mouth, resulting in great trade and relations one with the other, also great incomes from tolls and duties that the goods passing through have to pay.26

As in Amsterdam (or any number of Dutch port cities) waterways increased a city’s prosperity by multiplying residents’ opportunities to trade and network with other merchants. When controlled, they also, as Stevin commented, allowed authorities to collect revenues at checkpoints such as the weigh houses in Amsterdam. Rivers and canals linked agriculture in the interior to the ships that would distribute those natural resources. Controlled waterways symbolized a physical environment set in order: they facilitated communication, allowed goods to be transported in and out, and provided drainage, defense, sanitation, and checkpoints for levying duties.

The layout of Mauritsstad-Recife shows how seriously Johan Maurits’s planner took these principles. The city operated as an emporium via which goods could be imported and exported, a place where the waterways served both defensive and mercantile functions. Indeed, Johan Maurits wrote to the directors of the WIC that “nothing is more profitable than the sugar trade, except for the large revenues from taxation, duties and tolls.”27 Most important for our purposes, the map proclaimed this new city an economic center, a “staple-town” like Amsterdam — but located abroad.28

Possession According to Grotius

Maps that pictorially distinguished developed land from uncultivated areas underscored Dutch claims that they had the right of possession according to the international law of the time. In his articulation of property rights, Hugo Grotius linked the control of land to natural law. Building on Roman principles, Grotius based his ideas about property on what he considered man’s natural desire to protect himself from injury and provide for his own well-being — a right of self-preservation that he extended to political and corporate bodies.29 Nascent international law — then understood by Europeans as the “laws of nations” — had evolved out of colonial and commercial encounters.30 Grotius’s ideas about property and possession grew specifically from the argument he was asked to construct by the East India Company (VOC) to justify their capture of a Portuguese vessel.31 In Mare Liberum (1609), Grotius argued that the VOC, partially invested with sovereign powers by the States General, had the right to claim the captured Portuguese vessel Santa Caterina and its cargo as spoils of war. He argued that the Portuguese had no sovereignty (dominium) over naturally “free” and un-possessable waters. To that end, the Dutch could justly claim the treasure — treasure that did not belong to the Portuguese, but to the king of Johore — because of its presence in the open sea (although, of course, the VOC had no intention of returning it to the king of Johore).32 For Grotius, the seas could not be possessed because they could not be controlled. Grotius refuted the notion that possession could be obtained simply by seeing something. For Grotius, the right to claim “is not merely to seize with the eye (oculus usurpare), but to apprehend.”33 Oceans, by their very nature, are mutable, and would be impossible for anyone to “apprehend.” Thus, the claim of dominium by the Portuguese over the Indian Ocean was invalid.

What applied to the oceans also applied to land — simply seeing land did not provide entitlement to it. Although “looking” from the prow of a ship did not equate to possession, picturing the land in maps that showed organization and development fixed it and showed that it was controlled, and therefore possessed. In fact, the Dutch referred to maps as evidence of their possession of territories in the Americas.34 Moreover, in Roman law the testimony of the eyewitness was the most powerful evidence that could be provided (seconded by depositions from the eyewitness sources).35 It is no surprise, then, that Dutch maps and illustrated travel accounts from the period emphasize the eyewitness (recall that Visscher advertised this below the title on his news map of Pernambuco), along with such pictorial references to control as ships, government buildings, and the organization of the city in plans and bird’s-eye views.

Grotius’s Mare Liberum (1609) set the foundation for the more substantial On the Rights of War and Peace (De Jure Belli ac Pacis,1625). In this publication, Grotius provided specific discussion of instances applicable to municipal public and private law, as well as principles that could be applied to the new territories “discovered” by Europeans, or that could be legally possessed by right of victors in war. Certainly, the Dutch considered their conquest of Pernambuco part of a just war for autonomy, and they projected their conquests abroad as they did their victories at home: pictorially. Grotius maintained that possession by dispossessing the land from enemies in war was a legitimate means by which to claim ownership. In addition to land claimed by conquest, Grotius also argued that possession could be taken of unoccupied lands (res nullius).

In Roman law, possessed territory was formally enclosed, defendable, and occupied. If an area had never been occupied or had been abandoned, it was res nullius. When the Portuguese fled Recife, the land, its buildings and warehouses were abandoned, allowing agents of the WIC to lay claim to them. That the WIC could properly defend and further develop the area exemplified an important corollary to res nullius — the idea of improvement. Land must be built upon or engineered by tools and technology in order to be rightfully owned.36

Extended to Dutch colonial purposes, Grotius’s theories suggested that only settled and cultivated land counted as possessed. Grotius argued:

if there be any waste or barren Land within our Dominions, that also is to be given to Strangers, at their Request, or may be lawfully possessed by them, because whatever remains uncultivated, is not to be esteemed a Property, only so far as concerns Jurisdiction, which always continues the Right of the sentient People . . . So we read in Dion Prusaeensis . . . that they commit no Crime who cultivate and manure the untilled Part of a Country.37

For Grotius, if land was occupied, it was a person’s duty to produce resources to fulfill his own needs, and correspondingly, to contribute to the civitas (community).38

Possession and Development at Home

The orderly, reclaimed land of the Beemster provided a parallel at home to the Dutch demonstration of industry and control in the twin cities of Recife and Mauritsstad in the New World (fig. 7). In fact, much of Amsterdam as we know it today was built on land reclaimed during the first decades of the seventeenth century. Projects like the Beemster (1607–12) provided needed grain for bread, pasture for dairy cattle, and fields for bleaching linen and textiles. These were the domestic products shown in Visscher’s profile view and in maps of Holland. Unsurprisingly, the Beemster, like other reclamation projects, was undertaken as part of a joint-investment enterprise by some of Amsterdam’s more prominent burghers. The same Amsterdam merchants who heavily invested in overseas trading enterprises began to drain the Zuyder Zee in May 1607.39 By its completion in 1612, the Beemster was the largest polder in the Netherlands, imposing a rectangular grid structure on land reclaimed from the sea.40 It was an early modern planned community, consisting of lots intersected by roads and ditches. The Beemster’s water channels and roads were designed to facilitate agriculture on the polder.41

Many maps showcasing the Beemster plan were designed to attract investors and highlight Dutch ingenuity and wealth. Joan Blaeu included maps of the Beemster and subsequent reclamation projects in his multivolume Atlas Maior (1662–67, also published in French as Le Grande Atlas), thereby proclaiming these projects’ lasting significance to Dutch readers.

The explosion of land reclamation projects undertaken in Holland between 1600 and 1640 relied on the development of windmills that scooped water.42 As early as the 1580s, windmills, along with water and sugar mills, were highlighted as modern machines of industry. Jan van der Straet presented wind, water, and sugar mills as novel to the “modern” era in his Nova Reperta (ca. 1584). As he claimed in the captions accompanying pictures in his text, “The winged mill which now wants to be driven by the winds is said to have been unknown to the Romans” and “Whoever thinks water mills were invented in antiquity is completely wrong.” The text below the sugar mill (fig. 8) explains that the picture will “teach you by what art sugar is usually made.”43 Wind and water mills frequently appear in printed and painted Dutch landscapes and maps, which were often produced by Visscher, one of the earliest promoters of the rustic landscape as a print genre.44

Of course, mills were frequent sights in the Netherlands because they served so many important purposes for development: polder mills scooped water to make arable land from the sea, post mills ground grain, and others processed hemp, oil, and leather, and not least, the very paper that then was imprinted with images of the machine.45 Significantly, Visscher also published individual prints of windmills, including the emblem of a post mill found in Roemer Visscher’s Sinnepoppen (1614) that likened the unceasing communal work of the mill to that of a good prince.46 On maps, mills served as symbols of modernity and ingenuity working for the profit of the community. They were machines that processed natural resources from home and abroad into products for sale and consumption.

Likewise in Brazil, sugar mills processed natural resources into commodities. Such machines appear on maps of Dutch territories, where they served as indicators of the control and improvement of natural resources. In Blaeu’s later map of Pernambuco, the ox-powered mill on Visscher’s map was replaced by the more productive water-powered mill. Cane could be pressed in greater quantity and with greater speed by the water-powered mill.47 Here, too, then, the Dutch could demonstrate “improvement” of industry by means of maps.

Blaeu and Barlaeus’s Representation of Brazil under Johan Maurits

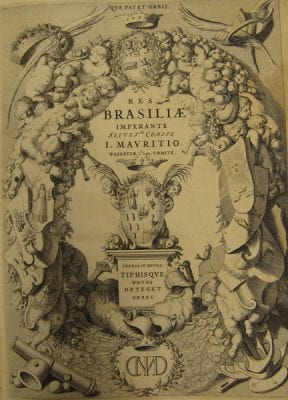

The maps Blaeu included in Rerum per octennium in Brasilia (1647) emphasize the development and control of the Brazilian landscape during Johan Maurits’s governorship (figs. 2-4).48 The WIC directors appointed Johan Maurits governor-general of their territories in Brazil in 1636, and he arrived at Recife on January 23, 1637. He was a worldly man, trained in the humanist tradition and raised as a prince with all the privileges and responsibilities such a social position entailed. His motto, qua patet orbis (as far as the world extends), showed his awareness of history and his ambitions for securing his place in it.49 Upon his arrival, Johan Maurits immediately set out to expand the Dutch presence in Brazil via both military conquest and the establishment of such visual markers as buildings and renovations.50 Yet after just seven years, in 1644, the directors ordered him to return to Holland. The reasons seem to have stemmed from his aristocratic conceptions of wealth and power, which clashed with the company’s desire for thriftiness.51

To secure his reputation, soon after his recall Johan Maurits asked Barlaeus to write a glowing history of his governorship. In addition to Blaeu’s map, the folio included fifty-five high-quality engravings after sketches of landscape views drawn by Frans Post, as well as topographical maps and ground plans after drawings by naturalist Georg Marcgraf and WIC surveyor Cornelis Golijath. Like the news maps by Visscher that included a composite of topography, plan, and profile view, Blaeu interspersed this combination of plates among the text to give a holistic sense of the landscape, one that underscored Dutch control via militaristic, civic, and commercial development, in this case specifically under Johan Maurits.

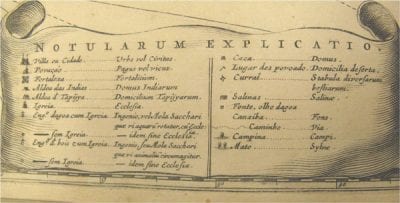

In the Brasilia, maps or ground plans are typically followed by a view of the landscape and the fort for each conquered town or region. A key in Latin and Portuguese marks the areas that Barlaeus considered worthy of rendering and clarifying for the reader (fig. 9). These include cities, churches, forts, aldeas (native villages), houses, stables, wells, the countryside (campina/campi), forests (mato/sylvae), and plantations (engenhos/ingenios), each marked by a little pictogram: for example, the countryside is marked by one tree, the forest by two trees close together. The landscape views by Post often include the diverse inhabitants of Brazil: the Dutch, Portuguese planters, enslaved Africans, and indigenous Brazilians, who generally lived in the aldeas overseen by Dutch officials.52 In ground plans and maps, the forests are represented by many trees, towns and cities’ walls and streets are outlined, and the boundaries between city and forest, cultivated and uncultivated land, are marked. The plans also provide information about the expeditions undertaken by Johan Maurits to establish military control. Dutch presence and power is reinforced by the marking of forts that the Dutch conquered or built, and by their ever-present ships shown patrolling the bays.

The first maps outline the coasts of the captaincies of Pernambuco and Paraíba. (figs. 2-3) The two maps were meant to be contiguous. They are linked by the outbuildings of the sugar plantation and symbolically, by the references to sugar on the captaincies’ respective emblems. The huts on the sugar plantation in the map of northern Pernambuco continue into the landscape of Paraíba. Pernambuco had long held the leading role as sugar producer, and Recife was the base of Dutch military and commercial operations. After the initial conquest in 1630, it was clear that the hill town of Olinda, the former Portuguese stronghold, and Recife could not both be maintained. Therefore, Dutch troops burned Olinda, preferring the rivers and harbors around Recife. Unlike Visscher’s view, which shows the Portuguese destroying the sugar warehouses and thereby relinquishing control, Blaeu’s maps do not show the Dutch destruction of Olinda. Rather, Barlaeus notes how Johan Maurits reclaimed Olinda’s masonry to build Mauritsstad.53

The act of reclaiming Olinda for Mauritsstad was highly symbolic of territorial control. As we have seen, the plan (fig. 4) shows the bounded territory of the city and its citadels, surrounded by rivers that connect it both to the interior, where sugar was processed, and to the sea. In addition to the city plan, Blaeu included views and plans of Johan Maurits’s palaces at Vrijburg and Boa Vista. These views, along with the sugar mill vignette in the map of Pernambuco (fig. 2), substantiated Johan Maurits’s development of the area. Barlaeus points out in one of the texts that Johan Maurits paid for his own palaces and adds that, as it had been for Roman commanders, it was necessary for Johan Maurits to build Vrijburg (and for it to be illustrated) as a show of power to impress and intimidate the enemy.54

Such visual intimidation proved necessary. The sugar plantations inland continued to be largely owned by Portuguese planters for various reasons: this was allowed in part to encourage peace with the enemy, but also because setting up milling operations was prohibitively expensive.55 However, the Portuguese who were unwilling to submit to Dutch authority post-1630 used the rural areas to stage guerrilla warfare, often burning their own sugar plantations to subvert Dutch rule. The Portuguese and their slaves continued their fight in the rural interior, and the inland area between Recife and Olinda grew unstable between 1630 and 1637, the year Johan Maurits arrived. His capture of Paraíba, just north of Pernambuco, formed part of his successful campaign to suppress guerrilla warfare in the countryside. In the bottom right of the map of Pernambuco the Dutch fleet is shown commanding the harbors and waterways, underscoring the superiority of Dutch military and naval power. In the map of Paraíba Dutch ships extend along the entire coastline (fig. 3).56

In the map of Pernambuco, Post’s addition updates the earlier visual motif of the sugar mill seen in Nova Reperta with details from his own sketches from life. He presents a new type of mill for the area, one that used water power to turn the sugar mill’s cylinders to press the cane.The picture emphasizes the mill as machine, relegating the human labor to small, seemingly insignificant components of the whole operation.57 (The three slaves by the mill would have pushed the cane between the moving cylinders for pressing at risk to their own limbs.) To the left, slaves lead ox-carts filled with already-cut cane to the mill. The road leading to the mill shows a Portuguese woman being carried to the plantation by her slaves, led by what must be the plantation’s owner. Behind the mill their two-story plantation house can be seen. There, more slaves raise their hands to greet the homecoming of the owners. This image provides a view of the sugar operations that sanitized and mitigated the awful reality of the forced labor necessary to run the mills; viewers are distanced physically and emotionally from the labor.58 Instead it emphasizes the military and mechanical engineering of modern civilization, where natural resources are extracted and exploited by human invention and labor. Such a pictorial emphasis corresponds to Barlaeus’s retention of the Latin ingenio and Portuguese engenho to signify plantations in the key.

The sugar mills’ mechanization parallels the silent and often unmanned mills depicted in Dutch landscapes. Both Brazilian and Dutch mills are positioned as inventions of human ingenuity and industry, machines that improve natural resources for consumption, ostensibly benefiting the common good. That some human labor was, in fact, necessary and dangerous, is hidden by the narrative of commercial enterprise, profit, and progress. In the Netherlands, the Dutch had used windmills to power their domestic economy; in Brazil, sugar mills processed cane into a lucrative commodity abroad.

Similarly, Blaeu’s map of Paraíba (fig. 3) uses pictorial means to indicate Dutch control of the interior, despite the uncertainty of Portuguese planters’ loyalty. To suggest Dutch dominance in Paraíba Blaeu chose the military expedition of Elias Herckmans to balance the picture of sugar production on the map of Pernambuco. Herckmans leads his troops under the Dutch flag, followed by indigenous Brazilians carrying provisions. According to Barlaeus, Herckmans led forty WIC soldiers and thirty-six Indians west along the Mongaguaba River into territory then unknown to the Dutch. It was as much a mission to intimidate and claim possession as it was “to explore this area and in particular its products.”59 Where no towns or ingenios existed, land was free to be cultivated by immigrants. In Barlaeus’s words:

[t]he Directors of the Company deliberated frequently about means for increasing the grandeur of the state, how they could attract immigrants, to be brought here and settled, spread out across the empty regions and uncultivated lands.60

Moreover, Barlaeus noted that on the expedition “the insignia of the Company were once more put up for the instruction and wonder of later generations,” and he concluded his description of the exploratory quest by stating:

Whoever reads this will agree that the Company, Count Johan Maurits, and the Supreme Council have left nothing undone that can promote the public good. They have sought to acquire profit by means of warfare, trade, and expansion of territory. Forests, mountains, rivers, or seas could not stop their quest for gain. Respect for money is so strong that it dares man to do the extraordinary and enables him to do the incredible, whether this means looking for hidden wealth or grasping for palpable riches.61

Here Barlaeus asserted a correlation between aggressive land acquisition and cultivation, commercial profit, and benefits provided to the community of Dutch citizens and subjects as a whole. For him, a civitas, a community developed by and for the good for all, necessarily included “warfare, trade, and expansion of territory.”

The emblems that Blaeu displayed on each map serve as a further pictorial means for asserting the “insignia” of Dutch control over sugar. In the map of northernPernambuco, a female personification of Pernambuco holds sugar cane, while the emblem for Paraíba consists of three bricks of sugar in cone shape (the cone bricks are also present in Van der Straet’s earlier engraving, fig. 8). Each emblem on the maps represents the commodities of that captaincy, and each scroll is capped by Johan Maurits’s crown and wings that figuratively extend as “wide as the world.” By picturing the commodities of the region allegorically, Blaeu used a conventional pictorial mechanism of possession, one he continued to use in the Atlas Maior.62 In maps and history books, coats of arms identified patrons and owners. The allegorical motifs of the Pernambuco and Paraíba maps, along with similar banners and decorative garlands, can also be found under Johan Maurits’s coats of arms and crowns on the title page to theBrasilia (fig. 10).

The pictorial program of the Brasilia underscored the control and development of Brazil under Johan Maurits and, by extension, the WIC. In Brazil, Johan Maurits built new forts and towns and rebuilt others. Just as important, he set up improved production and controlled the export of Brazilian natural resources, most especially sugar.

Conclusion

Although these maps by Claes Jansz Visscher and Joan Blaeu presented a view of a secure and economically stable Brazil, the historical actuality was, of course, quite different. The WIC had to use much of its hard-earned capital to maintain control of Pernambuco. Since the 1630 conquest, a complicated and expensive situation had prevailed for the Dutch company where Portuguese sugar planters were concerned. In order to increase productivity, and thereby increase duties from exports on sugar, WIC factors often sold slaves and equipment to Portuguese planters on credit.63 Furthermore, the WIC was embroiled in guerrilla warfare in the interior. In addition, although Johan Maurits was marginally successful in gaining territory in northeast Brazil and West Africa, the support he required made his governorship very expensive for the WIC. Despite — or rather, because of — their military gains, the WIC grew largely insolvent. After Johan Maurits’s recall in 1644, many of the planters’ debts came due. The planters’ desire to rid themselves of what were by many calculations impossible loans, afforded the Portuguese in Bahía the opportunity to foment revolt. Beginning in the early summer of 1645, Portuguese planters, supported by troops from Bahía, staged a series of uprisings. By 1648, the remaining Dutch officials and troops in Pernambuco were consolidated in Recife. Ultimately, the Dutch surrendered their last stronghold at Recife in January 1654.

Visscher published yet another map of Brazil in 1648 (fig. 11). The WIC’s charter had been renewed in 1647, along with a much-needed injection of 1.5 million guilders from the Dutch East India Company to support efforts in Brazil.64 Responding to these events, in this map Visscher combined views of Vrijburg, Mauritsstad-Recife, and the ground plan from the Brasilia. This map, too, is a composite that presented Brazil as a secure, stable, and controlled landscape, and it was printed for display exactly at a time when the WIC most needed to shore up investor confidence and support. As the eminent scholar of Dutch Brazil Charles Boxer has suggested, the capitulation in 1654 “came as a surprise to contemporaries, despite the pessimistic series of reports from the High Council at Recife . . . the strength of the fortification of Recife and Mauritsstad was a good deal overestimated in Europe, possibly because of books like Pierre Moreau’s Historie, which described Recife as one of the strongest places in the world.”65 It was not just such texts that claimed a strong Dutch hold on Brazil: maps were literally foundational to that view. In fact, Moreau’s l’Histoire de la Derniere Guerre faite au Bresil, entre les Portugais et les Hollandois (History of the Latest War in Brazil between the Portuguese and Dutch) from 1651 was printed in Dutch in 1652, and the frontispiece shows a detail of the very same map of Mauritsstad-Recife published by Blaeu and Visscher in 1647–48, complete with a fleet of ships in the foreground (fig. 12).

As images that helped form Dutch perception about the Atlantic world, printed maps from the second quarter of the seventeenth century were constructed using conventions informed by Dutch thinking about sovereignty, possession, and the desire for profit. The legal and political theories espoused by Dutch theorists in the early seventeenth century provided the WIC with a civic and pragmatic paradigm through which to claim and exploit territory both locally and abroad. Land and its resources were possessed in printed images that defined and emphasized how the Dutch developed, controlled, and made profitable land and its natural resources for the commonality. As we have seen, this framework for possession had its foundations in natural law, especially as articulated by Hugo Grotius. His ideas about property and natural rights prescribed order and hierarchy in the physical as well as political environment. Possessed land was land that was cultivated and controlled. Visscher’s news maps and the maps published by Blaeu in Caspar Barlaeus’s Brasilia served an important role as printed propaganda for the WIC, propaganda that helped shape public opinion about Brazil and its potential for military and commercial success. These maps proved possession and stability by all sorts of pictorial means, including the very nature of the space represented — a space that was claimed, built, developed, organized, and controlled.