This essay examines the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s use of the Dutch West India Company archives in the context of archival sources for the Dutch colony of New Netherland, which included parts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut (1621 to 1664). While the digitization of the WIC’s New Netherland Papers has provided scholars with invaluable access to information about the former Dutch colony, it has also placed undue weight on this elite, semi-private collection of documents at the expense of other archival collections.

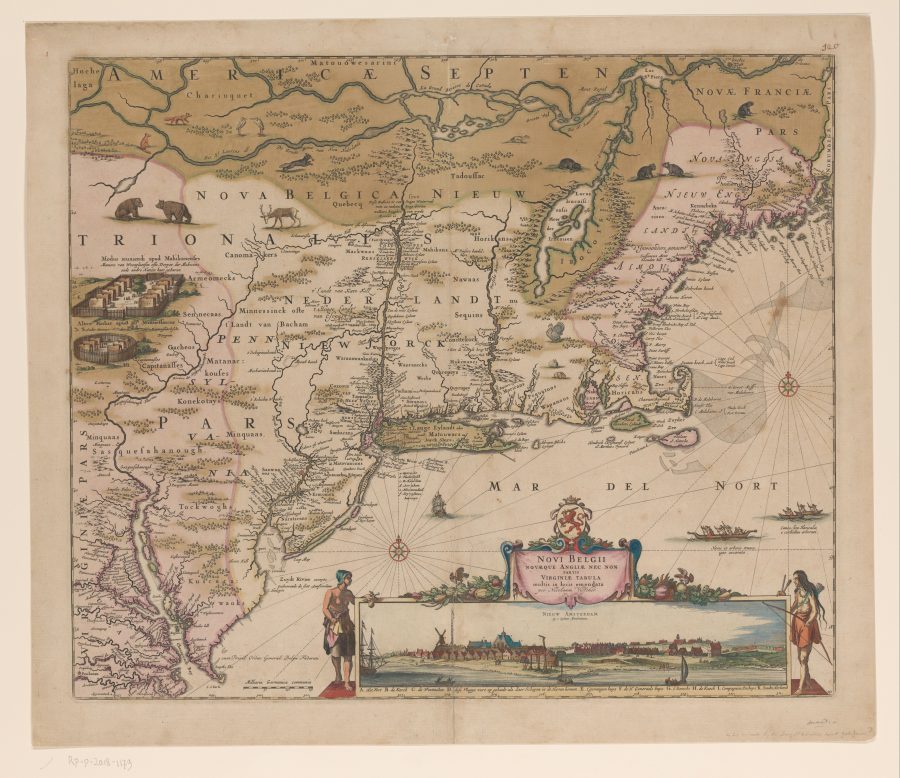

From 1609 to 1664, the Dutch claimed the North American colony that they christened “New Netherland.” Although now most strongly associated with New York, New Netherland included parts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut. Rooting their claim to New Netherland in Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage to the region under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and further articulating this claim with the New Netherland Company (1615–1618) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), the Dutch attempted to strengthen their hold on the land in the decades that followed by sending settlers over to occupy it. Although never as populous as New England or Virginia—its English neighbors on either side—the colony grew, particularly in the 1650s and early 1660s. It was also a robust node in a variety of networks, including regional inter-imperial trade and the broader Dutch Atlantic empire. With the fall of the Dutch colony in Brazil in 1654, the Dutch expended increasing energy planning for a lasting New Netherland (fig. 1). A decade later, however, the English took over the colony. Although 1664 represented a break in the political control of the colony as it moved from Dutch to English hands, Dutch culture and language remained significant presences through the American Revolution.1

In this brief piece, I aim to set the sources that the Dutch Textile Trade Project relies on—the VOC and WIC records—in a larger context. Although New Netherland is not included in the initial debut of Dutch Textile Trade Project data, which covers the period between 1700 and 1724, documents associated with the colony illuminate some of the promises and the pitfalls that arise when using company-produced archives. Carrie Anderson and Marsely Kehoe acknowledge and are well aware of the biases of company sources, as they explain in their introduction to the Dutch Textile Trade Project in this issue.2 I will not replicate their thoughtful analysis, which compellingly argues for the importance of reading documents alongside the visual and material archive and thus articulates the groundbreaking nature of the Dutch Textile Trade Project. Instead, I will focus on the issues that arise when we zoom in on one specific location within the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s broad geographical ambit and see how the project looks from that vantage point.

The New Netherland documents bear out the importance of the Dutch Textile Trade Project and its rationale: “Textiles—like the people that used them—have stories to tell.”3 When we focus on cloth, stories that lie just below the surface reemerge. To provide a brief example, cloth makes visible Jewish merchants and their trade with Indigenous people, a subject that has received minimal historical attention. Two anecdotes from the records will suffice to illustrate the point.

In 1656, Isaac Israel sued Jan Flaman, a skipper, for damages incurred when Flaman ran his boat aground in the South (Delaware) River. Israel, a Jewish merchant, had shipped a great deal of duffel (a coarse woolen cloth) in Flaman’s boat, and when the ship ran aground, the passengers used it to make tents and beds for themselves on the beach, leaving it in imperfect condition for trade.4 While the suit never mentions how or to whom Israel intended to trade the duffel, it is likely that it was intended for trade with Indigenous Americans.5 Either Israel planned to trade it directly with Indigenous people on the South River for furs, or he planned to sell it to local traders who would use it for that purpose.

Further south that same year, another Jewish merchant, anchored in Curaçao, tried to arrange trade with the island’s inhabitants. The WIC’s vice director on the island, Matthias Beck, initially tried to oblige the merchant to trade his full cargo with the WIC. The merchant refused, saying that he would only land his goods if permitted to trade freely with all the islanders. Desperate for provisions, Beck acquiesced, with the warning that the merchant could only trade with the Native people what they required “to clothe themselves” and nothing more.6 As these examples demonstrate, following cloth—which is a critical resource across cultures—gives a brief glimpse into an unanticipated link between Jews and Indigenous people in the Atlantic world.

Representative of the myriad stories likely to emerge from an exploration of cloth in the archives, these two brief accounts also raise questions about the Dutch Textile Trade Project, since they emerge from correspondence and court records in the West India Company archives rather than from the bills of lading on which the project relies. This raises questions about how to interpret the data in the Dutch Textile Trade Project, especially in the case of the Dutch Atlantic world, where the West India Company did not retain a trade monopoly (fig. 2). It also raises questions about how to gather data for future iterations of the Dutch Textile Trade Project, because company archives in the Netherlands are not the sole source of data for trans-Atlantic trade. On the contrary, non-company archives contain highly relevant material as well.

For example, the records of New Netherland include both company-produced and non-company produced documents.7 In the case of New York, where the bulk of the material resides, these documents are divided among multiple repositories across the state, with different collection access points and variable levels of catalogue description and digital access.8

The largest repository for New Netherland documents on either side of the Atlantic is the New York State Archives (NYSA) in Albany, New York.9 In partnership with the Nationaal Archief of the Netherlands, the NYSA digitized its entire collection of New Netherland documents, including the two accounts discussed above, and made them available in an open-access environment.10 This digitization represents thousands of pages of text and is an incredible achievement, especially because many of these documents sustained significant damage in the 1911 Capitol fire in Albany. The infrastructure around these digitized papers, which makes them comparatively easy to use (if one knows seventeenth-century Dutch), is minimal. Unlike the Dutch Textile Trade Project, a true digital humanities project, the New Netherland documents project is a digitization project. It is meant to give interested parties easy access to the documents and to add another layer of protection to guarantee their survival for succeeding generations. Its simplicity is also important for ensuring that the interface remains viable for as long as possible.

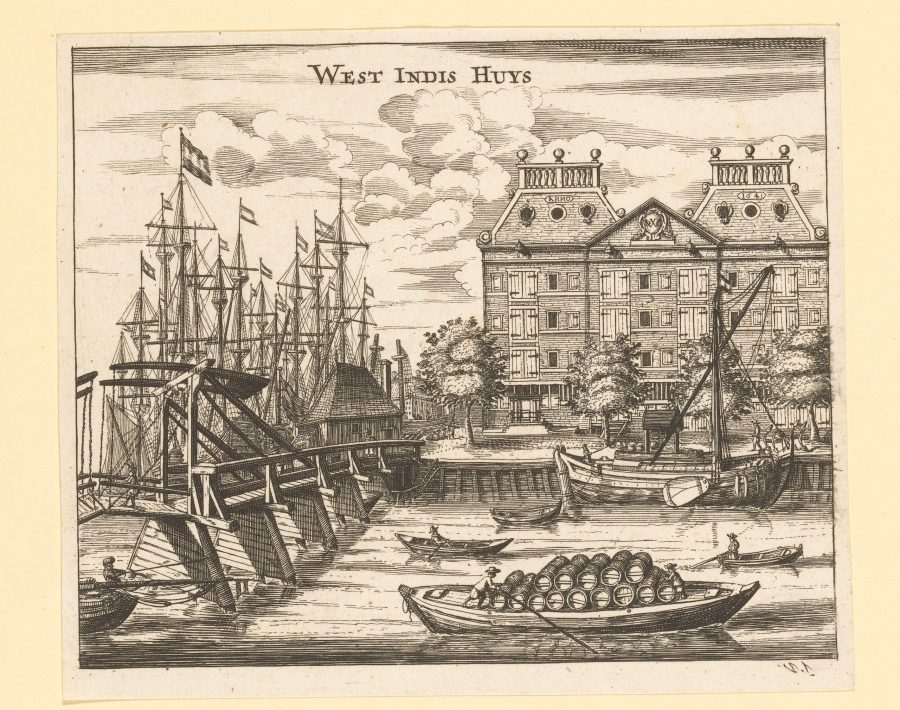

But as Anderson and Kehoe also warn, reliance on company-produced documents is fraught.11 The mission of the NYSA is to preserve the documents related to the government of the state of New York, and this mandate has been understood to commence with documents produced by the Dutch West India Company’s government in New Netherland (fig. 3). The decision to preserve these documents began with the English takeover in 1664 and continued with each succeeding governing regime. Each of these new governments preserved these documents because they are understood to be part of a paper trail that lent legitimacy to each succeeding state.

The archives related to New Netherland in the United States are vast—and this does not count the many New Netherland-related documents that exist in the Netherlands. There is a high barrier to entry when it comes to the full archival landscape, as overlapping jurisdictions produced different documents that are now housed in different locations. It is important to recognize exactly what is—and what is not—part of the NYSA’s collection. Discussing the conditions that led to the creation and preservation of this archive, and communicating all of this effectively to scholars and the public, is imperative. The Dutch Textile Trade Project may also find itself thinking about similar issues in the future.

The point of contact with the New Netherland documents for many scholars will be the archives’ website. However, the limitations of NYSA’s collection are not always clear online. The New York State Library (NYSL), for instance, is housed in the same building as—and even shares a research room with—the NYSA, the home of the digitized Dutch West India Company papers. And yet, few researchers may know of the important collection of Dutch documents housed in the NYSL called the Van Rensselaer Manor Papers. These papers, which concern the management of the Rensselaerswyck patroonship, are also numerous, but they remain in poor condition and have not been digitized. Because they were not part of the state’s mandate, they were not initially prioritized for preservation and digitization. They also contain a number of account books that, relevant to this issue’s context, contain many records of textiles.

The value that governments—whether in the United States or in the Netherlands—place on certain records above others leaves vast gaps that need to acknowledged. Both the United States and the Netherlands have prioritized company documents because these companies are precursors to modern states. The ease with which some documents may be accessed over others means that we leave the telling of those other histories only to the best resourced. For example, the focus on the governmental collection has given the impression that the use of the Dutch language in written documents ceased after 1664 in New Netherland. This is not the case with private citizens, who continued to write in Dutch in the decades after the English arrived.12 When we do not attend to these more widely dispersed and more difficult-to-access documents, which are often more colloquial and challenging to read and interpret, we miss a great deal of the story. Company-produced documents are an extremely important resource to historians, but as we draw from them, we still need to think about them in the context of other texts.

The Dutch Textile Trade Project is a major achievement from which we will glean insights for years to come. Its global view and its rejection of the conventional historical separation of the Dutch East and West Indies are some of its greatest strengths. At the same time, we still need to think about how to tell textile stories from local perspectives. This brief overview of New Netherland’s records suggests some of the ways that this might be done: by going beyond bills of lading in company documents and by going beyond company documents altogether. The trading companies and the Dutch state are not synonymous with one another, and I look forward to seeing the Dutch Textile Trade Project—which has already accomplished so much—grapple with this issue in the future.