From the refined silk used to make japonse rokken to the coarse cotton of laborers’ shirts, textiles have long been critical indicators of rank and status in the visual culture of the early modern Dutch Republic and its global networks. And yet, due to the complexity of the trade, the ways in which these textiles generated meaning is not easy to discern. With these concerns in mind, this essay debuts the preliminary findings of the Dutch Textile Trade Project (dutchtextiletrade.org), an ongoing, collaborative digital art history project that brings together four types of data (textual, material, visual, and quantitative) in an effort to advance the study of historic trade textiles and their social meanings.

Introduction: Textiles on the Move

On May 2, 1709, the Dutch East India Company (VOC, for Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie) ship Baarzande departed the port of Surat in northwest India, carrying 25,500 textiles of varying lengths and 15,081 pounds of indigo, all of which was produced or harvested in the surrounding region and acquired through Gujarati merchants and brokers in the port.1 When the Baarzande arrived in Batavia (today’s Jakarta) a few months later, the ship’s documents, including the inventory of cargo, were checked carefully by company officials and copied by clerks into the ledger of the Bookkeeper General, who noted the cargo’s value at more than sixty thousand Indian guilders. Laborers unloaded the cargo into Batavia’s warehouses to await repacking onto ships for trade or diplomatic voyages across Asia or to be divided up among the many ships of the annual fall Return Fleet to the Dutch Republic. 3,960 nickanees (a striped cotton cloth) from the Baarzande were joined by textiles from the ship Grimmestein, including 19,840 salempores (inexpensive white or brown cottons), 600 pieces of fine, hand-painted chintz, and 200 pieces of gingham taffachelas, all of which came from India’s Coromandel Coast.2

At the end of November 1710—just over eighteen months later—eleven ships left Batavia in that year’s Return Fleet, including the Mijnden, which was loaded with nickanees, salempores, chintz, and gingham among its nearly 40,000 textiles; 328,689 pounds of black peppercorns and other spices; ambergris; Persian wool and leather; and dyewoods—a cargo with a total value of 417,112 Indian guilders; 283,087 for the textiles.3 Each ship carried documents detailing its cargo, which would eventually be copied into the central records of the Dutch East India Company. Along the route around the Cape of Good Hope, these eleven ships were joined by three company ships coming from Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), and two more that left Batavia in January but caught up to the fleet. If you were in Haarlem on Thursday, August 6, 1711, you could read all about this fleet and its combined cargo by picking up a copy of the Oprechte Haerlemse Donderdaegse Courant, a two-page newspaper with news of Europe and the world. Six of the eleven ships were destined for the company’s Amsterdam chamber, and their goods were unloaded and stored at Amsterdam’s Dutch East India Company warehouse.

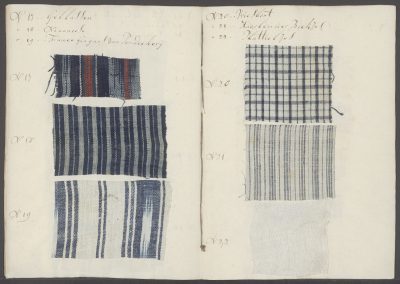

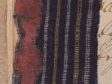

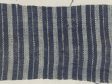

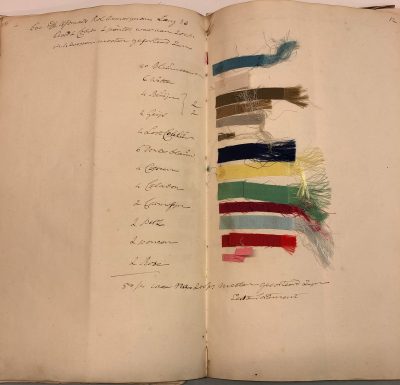

Textiles stored in the VOC warehouse were eventually purchased by merchants at auction to be sold at local cloth shops, perhaps similar to the one pictured in Matthijs Naiveu’s 1709 painting at the Museum de Lakenhal (fig. 1). Here, a well-dressed woman examines a fine piece of embroidered gold brocade, as a man and woman behind the counter prepare to record the sale in their ledger. Not all VOC textiles were sold in high-end shops like these, however. Many were purchased by local merchants to be sold to the Dutch West India Company (WIC or GWC, for Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie), and eventually loaded onto ships headed to West Africa and the Americas. In some cases, the WIC cut out the middleman and purchased goods directly from the VOC, which suggests the two companies enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship. Later sample books, like the one that traveled on the WIC ship De Vrouwe Maria Geertruida, show us what some of these more common trade textiles might have looked like, marking a striking contrast to the gold brocade in Naiveu’s cloth shop (figs. 2, 3). Notably, most of the textile samples on these pages were made in India and probably brought to the Dutch Republic on VOC ships.

Ship manifests and cargo lists carefully record the quantities and prices of these trade textiles as well as their Atlantic destinations. For example, on July 31, 1712, the WIC ship Acredam left Amsterdam for the so-called Guinea Coast (West Africa) with more than fifty-five thousand Dutch guilders’ worth of commodities in its hull, including taffachelas and nickanees (Indian-made cotton textiles), perpetuanen (a European-made wool fabric), slaaplakens (linen bed sheets), servietten (napkins), platillas (fine white European linen), and graatjes (a white cloth of unknown origin).4 Of the total 2,117 pieces of taffachelas and nickanees on board the Acredam, 1,518 were purchased directly from the Dutch East India Company. In addition to textiles, the Acredam also carried other commodities, such as iron rods, pitchers, cowrie shells (also purchased directly from the VOC), and brandy. All of these commodities—but especially the textiles and cowries—were used as currency in the Atlantic slave trade, either to purchase enslaved people from African traders or to facilitate that trade.5 The journey of these commodities—which were transported from India to Indonesia, Europe, and West Africa—illustrates the interconnectedness of the Dutch East and West India Companies, which were united by the forces of an emerging global economy.

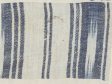

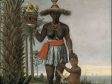

Michiel van Groesen has recently called into question the historiographical divide that has arisen between Dutch East and West India Companies, issuing a call for “new methodological possibilities for historians willing to dismantle the divide between East and West.”6 In response to this scholarly lacuna, our ongoing and collaborative digital art history project, the Dutch Textile Trade Project, recognizes textiles as one of the core commodities that connected the two companies.7 Not only were textiles avidly desired by consumers in Europe; they were critical for trade in every region of the world. But whereas the lion’s share of critical attention has focused on elite silk garments like the one worn by Amsterdam burgomaster Johannes Hudde in his portrait by Michiel van Musscher (fig. 4), we contend that more common trade textiles—like the blue-and-white cloth worn by the Javanese woman in a drawing after Andries Beeckman (fig. 5)—should be treated with equal measure, for these were the textiles that underwrote the material affluence of Amsterdam’s elite.

Across the continents, Dutch ships needed to carry an abundant supply and variety of textiles to meet the needs of a range of consumers, a testament to the already well-established global textile market. This trade was highly competitive, and success hinged on being able to provide those designs and fabrics that were most sought after by local traders. European merchants were almost always responding to local taste and demand, rather than introducing “novel” fabrics into a hungry or depleted market. Consequently, our project does not prioritize the economic-driven perspectives of Dutch VOC and WIC merchants and administrators, even though we draw from the extensive records they maintained. Rather, we seek to read against the grain of these documents in an effort to understand how shifts in textile price, quantity, color, and pattern were determined by changes in local patterns of consumption. Local consumption, we argue, can teach us a great deal about how these textiles generated meaning in the communities in which they circulated.

This essay debuts the preliminary findings of the Dutch Textile Trade Project (dutchtextiletrade.org), an ongoing, collaborative digital art history project that features a Visual Textile Glossary, interactive web applications, and twenty-five years (1700–1724) of downloadable textile data drawn from Dutch East and West India Company archives.8 The Visual Textile Glossary, which will expand as more research is completed, currently features ten illustrated entries, a fraction of the more than three hundred textile terms found in company archives. It is our contention that these textiles—like the people that used them—have stories to tell. The aim of our project is to recover these stories, many of which have been lost to the destructive forces of colonialism and the bureaucratic legacy of the archival record. In an effort to make visible the “human” in “digital humanities,” we do our best to explain the intellectual choices we have made in compiling our datasets, which—like the colonial archives from which they draw—were neither neutral nor uncomplicated. By making our choices transparent, we highlight the intellectual labor that directs the work of digital humanists in order to undermine the perceived impartiality of such endeavors.

The first section of this essay gives a brief history of the Dutch trading companies and the critical role that textiles played in trade on a global scale. The second section turns to the archival documents that provide the economic data for our project. In this section we also present both the ethical and practical challenges of working within the documentation of the two companies’ administrative systems. In the third section, we consider the challenges of working with the extant material textile record, which—due to traditional museum collecting practices—favors expensive garments worn by the economic elite over the lower-quality textiles that drove the global textile trade, a situation that ultimately reinforces certain asymmetries of power. In the fourth section, we turn toward the pictorial record, focusing on several case studies that try to disentangle pictured textiles from the iconographic conventions that bind them. In the final section, we present the Visual Textile Glossary—which has its debut in this special issue—which joins together economic, material, and visual data in order to gain a deeper, more critical understanding of the global circulation of textiles in the early modern period.

The Companies and Their Textiles

The first Dutch efforts in overseas trade were economic and political in that they began with a challenge to the Portuguese monopoly on the Asian spice trade and were forged in the context of the Dutch War of Independence from Spain.9 Following the advice of Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, who had sailed on Portuguese ships to India and Asia and published an account of his experience, in 1594 Dutch merchants began organizing a fleet to explore trading possibilities. This Eerste Schipvaart (first voyage) returned in 1597 with proof that the Portuguese monopoly could be broken. Over the next few years, more fleets were organized, and in 1602 the Dutch Republic chartered the Dutch East India Company to concentrate this effort and establish a Dutch monopoly on the spice trade. After the Twelve Years’ Truce, the Dutch West India Company was chartered in 1621, with a similar charge. The East Indies, for Dutch purposes, included everything from the Cape of Good Hope eastward to Japan, while the West India Company was limited to the Atlantic trade.

Both companies were headquartered in Amsterdam and run by boards of directors representing regional interests.10 Their charters included the right to represent the Dutch Republic abroad, to pursue treaties with local governments and use military force against competitors, and to foster trade. These companies were financially supported by private merchants and citizens who bought and traded shares of the companies. Smaller Dutch trading companies focused on specific regions or goods and negotiated with the Dutch government or other trading companies for specific rights or were absorbed into these companies. Notable examples include the Middelburghse Commercie Compagnie, which became deeply involved in the Dutch slave trade beginning in 1730, and the short-lived New Netherland Company (1615–1618), whose territory was absorbed by the WIC. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the trading companies were the primary way that the Dutch conducted business and politics outside of Europe. Only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were Dutch territories abroad absorbed into the Dutch state and officially made colonies of the Netherlands.

Although the Dutch first entered the Asian maritime trade seeking spices, it quickly became clear that Indian textiles, rather than European goods, were the primary currency of interest. Indian cottons were in high demand in Maluku (the Spice Islands), throughout Southeast Asia (island and mainland), and as far east as Japan. Woven Chinese and Persian silks were also desirable across this network, and related products, including unprocessed and spun silk and cotton fiber, were imported to Europe for use in local textile manufacture. By the second quarter of the seventeenth century, the Dutch textile market was centered on Batavia, the VOC capital, where textiles (and other goods) were warehoused for shipment to elsewhere in Asia and to the Dutch Republic. When Dutch merchants recorded their exchanges, they preserved the value of this trade in Dutch currencies, although trade was also conducted with goods and many other international currencies. Massive amounts of European silver (much from the Spanish Americas) also moved into this network, especially into China and Japan.11

Textiles were also important items in diplomacy, as the Dutch exchanged gifts with sultans, rajas, kings, and merchants across the region to obtain favorable trading conditions. These gifts, many of which are carefully itemized in VOC cargos, included expensive textiles: cottons from India and Bengal (like chintz, muslin, and salempores), Persian velvets, and European red and black laken (linens or cloths), alongside tobacco and weapons, with utilitarian dongris (a sturdy cotton cloth)12 wrapped around the gift bundles for protection and presentation. In 1711, for example, the VOC ship Gent departed Batavia for Makassar, with gifts for fifteen officials, all of which included textiles.13 The largest gift, to raja Boni, consisted of fifty-seven pieces of textiles (of both European and Asian derivation), along with some rolls and ells of the same, plus guns and tobacco, and for packing, two pieces of dongris and a chest. The smallest gifts, to the two letter-carriers, consisted of five pieces of cotton textiles: one each of sollogesjes, chintz, and muris, and two pieces of salempores, with a quarter piece of dongris for packing. When the Gent returned to Batavia in June, its cargo hold was filled with rice.14 The textiles in these gifts were counted in pieces or measured in ells (a unit that varied across Europe but was approximately twenty-seven inches, or sixty-nine cm). In contrast, when moving as trade items, textiles traded in bulk, hundreds or even thousands of pieces of a textile type moving on each ship.

In the Dutch Atlantic, Asian and European textiles were traded for local commodities like ivory, gold, tobacco, sugar, and, reprehensibly, enslaved people. Textiles also played a critical role in intercultural negotiations, where they were used to facilitate or encourage trade and to build diplomatic alliances. The following example is somewhat typical of how such negotiations proceeded. In 1701 Joan van Sevenhuysen, the Director-General on the West African Gold Coast from 1696 to 1702, sent WIC employee David van Nyendael (1667–1702) into Asante territory to create an alliance with Asante King Osei Kofi Tutu (ca. 1660–ca. 1717).15 Nyendael and his envoy were sent with gifts and “extensive instructions on how to behave,” the prescriptiveness of which suggests the importance of this diplomatic endeavor.16 The gifts to be presented to Osei Tutu and his entourage included velvet and silk textiles, a large gilt mirror, a helmet, sheets of gilded leather, and bottles of brandy.17 After presenting the gifts, Nyendael was instructed to request permission to trade freely and without impediment in the region; he was also told to provide the king and his entourage with a list of the types of products—and their prices—that would be available through WIC merchants, which included slaaplakens and other textiles, mirrors, knives, and beads, among other items.18 Not only were textiles a critical element of trade, but the presentation of textiles could constitute an important prerequisite to the trade itself. Given the importance of textiles for trade in the Dutch Atlantic—especially on the western coast of Africa—merchants attempted to supply their ships with textiles of the specific types, colors, and patterns desired in local markets.19

The textiles imported into Dutch-occupied regions of Africa and the Americas reflected the global reach of the Dutch trading companies, which—over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—circulated enormous quantities of textiles throughout the world, including Indian cottons, raw silk from Persia, and European woolens, linens, and velvet, to name only a few. But while the geographical origins of the textiles transported on Dutch ships reflected the breadth of the Republic’s mercantile interests, the destinations and the uses of these textiles-in-transit were wholly determined by the local needs of their consumers in African and American markets. For example, osnabruck—a coarsely woven linen—was preferred by the so-called Brasilianen, an Indigenous group in Brazil who were essential allies of the Dutch West India Company in their defense against the Portuguese. To maintain this critical alliance, the Dutch had to ensure that the Brasilianen were well stocked with linen, which they presented to them as both gifts and payment for their services in the Dutch militia.20 Duffel, a coarse woolen European cloth, was preferred by Indigenous traders in New Netherland because it could be wrapped around the body like a garment during the day and used as a blanket at night.21 Slaaplakens,22 which according to some European observers became incorporated into various ceremonies and everyday rituals on the west coast of Africa, were shipped in staggering numbers: between 1703 and 1724, for example, more than six hundred thousand pieces were sent on WIC ships to various locations on the African coast.23 In addition, textiles procured in Asia by VOC ships were sent to Europe, repackaged, and then loaded on WIC ships to be traded in Africa and the Americas. These included loom-patterned textiles made in India, such as guinea cloth (discussed below), which were especially popular on the western coast of Africa. Chintz also appears on WIC cargo lists, as does the occasional Japanese robe (japonse zijde rok; see Angelina Illes’s essay in this issue), demonstrating the wide range of textiles that found a market in Africa and the Americas.24 The WIC also participated in the complex and competitive inter-African textile trading networks, especially between the Benin Kingdom and the Gold Coast, shipping 12,461 pieces of the Benin cloth called mouponoqua to the Gold Coast between 1633 and 1634 and another sixteen thousand between 1644 and 1646.25

As these examples demonstrate, textiles were essential elements of trade in all contexts where the Dutch established relationships across the world, both where Dutch trading posts were built on colonized land and where Dutch merchants interacted with local brokers. European and Indian-made sailcloth propelled Dutch ships; textiles purchased in India entered into the sophisticated trading networks of Asia and Africa; and textiles were essential gifts—and packaging for those gifts—for establishing and maintaining diplomatic and economic relationships globally. The Dutch produced vast and detailed documentation of these transactions, which are a critical source for the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s datasets, discussed in the next section.

The Written Record: Documentary Evidence of the Textile Trade

The Dutch East and West India Trading Companies are known for their bureaucratic scrupulousness, having left copious records of their administrative activities in former colonies and trading posts across the globe. These documents, in turn, have been carefully preserved by the Dutch state and local archives, and in the past few years many of them have been photographed and made available online, their accessibility enhanced through the development of tools like Transkribus, which allows for the transcription of and text search within these manuscript documents.26 These records contain vast amounts of data related to the commodities trade, including quantitative information like prices, quantities, and dimensions; spatial and temporal data that chart the movement of goods between ports; and qualitative data describing goods, including some terminology that has become largely obsolete. While these data are vast, the documents are not always legible or complete, nor are they entirely consistent. Some scholars have used these data to quantify the total value and proportion of this trade, while others have worked to understand, where possible, the meaning of a specific term in a place, time, or context.27 The former approach tells us that this global textile trade is important without clarifying how and why, while the latter has been unable to tell the full story satisfactorily. Computational methods have great potential for making sense of these vast data about tradable goods like textiles, beads, weapons, tools, and enslaved human beings, the values of which were carefully and callously calculated by Dutch merchants—but doing so also threatens to reinscribe the violent history of the documents themselves.28 Put another way, there is a danger in enlisting these archival data in the service of historical positivism, for it perpetuates the excision of human agency that underpins the Dutch imperialist agenda. Many scholars have turned to these archives in an attempt to understand better how the companies contributed to early modern global trade networks, but few scholars examine how the structure of the archives themselves advanced the companies’ agendas, a consequence of global expansion that is also—and perhaps more easily—legible in contemporary artistic production, as discussed below.29

The social and cultural importance of these documents is not insignificant. In fact, we argue that the archival records of the Dutch companies comprise an important part of the “cultural archive,” which—as Gloria Wekker has conceived of it—“foreground[s] the memories, the knowledge, and affect with regard to race that were deposited within metropolitan populations, and the power relations embedded in them.”30 As Wekker has argued, the modern Dutch “cultural archive” has a deep and layered history that is inextricably bound to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which mark the inception of the Dutch colonial project. In the wake of the digital turn, it is imperative that the structural inequities of power ingrained in colonial archives are not reified and perpetuated in the emerging “digital cultural archive.” Roopika Risam has written eloquently about the important role that humanists must play in “developing and sustaining the digital cultural record of humanity,” pushing back against critics who worry that the digital humanities will “supplant that which is ‘human’ about the ‘humanities.’”31 Indeed, we recognize this project as a part of the emerging digital cultural archive and, more specifically, as part of a larger body of postcolonial digital scholarship, which collectively seeks to push back against narratives that prioritize the Global North perspective due to its relative authority and economic wealth.

Recent reexaminations of Dutch archives have foregrounded the ways in which administrative documents can both reflect and generate social hierarchies and power imbalances. Some historians and art historians are highlighting the ways in which the semantic structures of the archival record can hide or obscure long-neglected historical voices (which have also been simultaneously subsumed by the dominating narratives of “Golden Age” artists working at the height of the Dutch Republic’s prosperity).32 For example, Mark Ponte’s essay for the Rembrandthuis exhibition Here: Black in Rembrandt’s Time debuts archival research that traces a growing community of Black people—oftentimes sailors and current or former servants—living in close-knit neighborhoods in areas near Amsterdam’s Jodenbreestraat, not far from Rembrandt’s home. Ponte examines a range of documents that shed light on these communities, including registers of cemeteries where the Black servants of Portuguese Jews were buried, and especially marriage and baptismal records and wills. Similarly, the Rijksmuseum’s recent Slavery exhibition brought attention to the lives of neglected historical figures by contextualizing names mined from the archival record.33 In her work on free and enslaved women in Barbados, Marisa J. Fuentes provides a model for simultaneously building compelling and devastating stories around figures who left only traces in archival documents while interrogating how the archives have reduced her subjects to generic, objectifying, repeated terms like “slave.”34 The current project takes a different approach. Rather than reconstructing histories by providing context related to isolated pieces of archival data, we are taking what is often referred to as a “distant view,” examining large amounts of data from across many archival documents in order to see patterns not clearly visible up close, which we hope will provide a broader framework in which to situate human experience.35

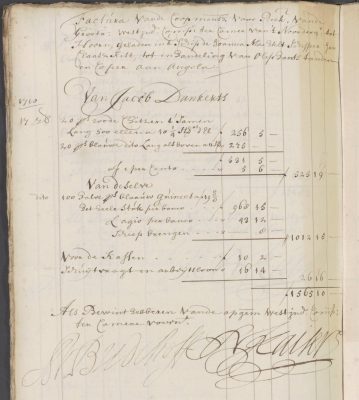

Together, the East and West India Companies produced an astounding number of administrative documents of a variety of types—1.36 kilometers of documents in the Dutch National Archives and more in archives worldwide. In this rich archival record, the textiles that were carried on company ships are quantified and priced according to their material attributes. This documentation is important because few of the textiles traded in the Dutch network during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries survive today, making it hard to identify extant samples of many cloth types, especially those with names that are now obsolete. One of the most valuable types of documents when it comes to textiles is called a factuur (pl. facturen), or invoice, an itemized list of goods describing the contents of a given ship, along with the person or entity who supplied the commodities listed. Many of these documents are preserved as manuscripts in the Dutch National Archives for both companies. The facturen and other ship documents are the sources of cargo lists compiled by company bookkeepers in journals and ledgers, of which multiple copies were made and distributed to the various company offices. The VOC compiled and published printed cargo lists for ships returning from Asia, distributing these broadsheets among merchants in the Dutch Republic. This information was even reprinted in newspaper reports, suggesting a somewhat broad public interest and relatively wide distribution.

The various versions of these documents list each textile, generally with quantities and prices for each type of cloth. The textile names are often augmented with modifiers further specifying the type of textile. Color was perhaps the most frequent descriptive category used in these documents, especially blue, white, red, and green. A factuur from the Joanna Machteld, for example, lists twenty pieces each of red and blue chintz, along with one hundred half-pieces of blue guinees (Indian cotton cloths), along with their corresponding prices in guilders (fig. 6).

Sometimes textile descriptions were further modified with indications of particular patterns, like striped (gestreept) or checked (geruit, geblokt).36 Textiles might also be described by their origin, such as “Haarlem” or “Malabar,” modifiers that must have been a clear indication of the cloth’s physical properties for merchants at the time but in many cases are incomplete or ambiguous to readers today. In another example, the textile’s origin was used to indicate its authenticity (and thus justify the price), as was the case with the 114 pieces of chintz carried by the WIC ship Adrichem in 1714, which were described as inlandse (native), presumably to distinguish them from the imitation chintz being produced in the Netherlands and England at the time.37 Size is also an important metric of value in archival documents. Lengths were typically measured in ells or the more ambiguous “pieces” (the dimensions of each piece vary by textile type and loom construction and could also vary within a given textile type).38 Textile modifiers might also correspond to tactile, material qualities, as when a textile was described as “fine” or “coarse,” attributes that were dependent on both the textile type and the density of its warp and weft.

Although the VOC and WIC archives are rich in basic adjectival textile descriptors, there is still a great deal that gets lost in translation from object to text, and thus this information must be interpreted carefully. Merchants and clerks had greater or lesser knowledge of the textiles they were describing and would have left off descriptors that were common knowledge. For example, when a given textile is described as “blue,” it might indicate a textile that was woven of white or undyed threads and then piece-dyed blue, or a textile with some threads dyed blue and then woven in a striped or checked pattern—and rarely is any indication given of the particular shade of blue. One might also be left wondering what exactly a “striped” textile looked like. Were the stripes thin? Thick? Were they evenly spaced or irregular? Unless a swatch book was included in the records—which was not common until later in the eighteenth century—this information is rarely provided.

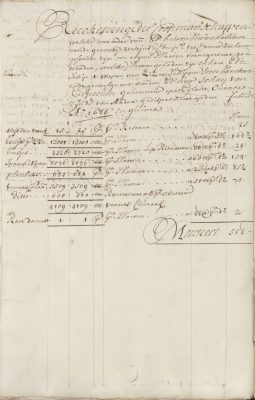

The facturen on which our dataset relies indicate value using the tripartite system of Dutch currency: guilders, stuivers, and pennigen. In colonial-occupied regions, however, value was determined by the relationship between commodities, rather than in currency—often goods were traded directly for other goods, or, when money was exchanged, it was not always in the same currencies and denominations indicated in the facturen. As the Slavery exhibition at the Rijksmuseum recently brought to public attention, both Dutch companies—East and West—were deeply involved in the Atlantic and Asian slave trades, which meant that some of the commodities against which these textiles were valued were human lives, made clear in the cold secretarial precision of documents that record the exchange of commodities.39 Figure 7, for example, shows that 684 pieces of platillas40—the white textile shown at lower right in fig. 3 and mentioned in the introduction—were worth the equivalent of 85 1/2 enslaved people. This horrific document makes clear that our choice to use the valuations system of the facturen (Dutch or Indian guilders) as a point of comparative value risks sanitizing this ugly history. We do so not to absolve this trade of its horrors but so that values can be computationally compared across time and space. It is imperative to us as scholars and as humans, however, to provide reminders that these documents and this trade were not and are not inert, neutral tools of accounting. Transparency about the choices we have made in aggregating these data into digital form is a critically important responsibility for anyone working with colonial archives such as these.

What is also left unwritten in the documents is any indication of the social significance of each textile type—either before or after it was loaded onto Dutch ships—a consideration that certainly would have been beyond the scope or purpose of the factuur, the primary concern of which was to justify the values of the commodities itemized on its pages. But while a factuur would naturally exclude any consideration of a textile’s social importance, it also draws attention to the state of latency that such documents prescribe, one in which an object’s “social life” is temporarily suspended, trumped by its commodity status.41 Slaaplakens offer an important case in point because they have a rich and rarely acknowledged history on both sides of the Atlantic—a history that is both revealed and obscured by the formal structures of WIC documents. In WIC facturen, for example, the practice of recording the merchant’s name along with the commodity reveals that slaaplakens were almost always sold to the West India Company by women, which suggests that the selling of bed sheets offered women living in the Dutch Republic the opportunity to generate household income. Of the more than six hundred thousand slaaplakens sold to the WIC between 1700 and 1725, 60 percent of them were sold by women—and likely many more.42

The critical role that women played in supplying the WIC with slaaplakens is visible in the facturen because “merchant name” is a recoverable variable. But these documents tell us nothing about how these textiles were used in an African context. For this, we are in large part dependent on European travel accounts, which are culturally biased at best and must be interpreted cautiously. For example, Pieter de Marees, the former WIC employee who wrote the 1602 text Description of the Gold Coast of Guinea, notes a preference for “Holland linen” (though not slaaplakens specifically), which was sold in a market in Elmina and local consumers cut “into strips which are only about the width of one hand and use these instead of girdles around their bodies.”43 This comment suggests that they were cutting linen to approximate the dimensions of textiles produced on an African strip loom, which was widespread at this time and which measured about seven to nine inches in width.44 While De Marees may have been referring to bolts of cut linen, later writers are more specific. Samuel Brun, a German barber-surgeon under the employ of the WIC in the second decade of the seventeenth century, wrote of his 1617 voyage to Fort Nassau in Moree (Mori) in current-day Ghana in his 1624 book. Of a local wedding ceremony, he describes “a white garment, which may consist of an old linen sheet that they have obtained from us and consider to be an elegant garment.”45 Danish West India Company employee Ludewig Ferdinand Rømer, who lived in and around the Danish headquarters at Christiansborg Castle in current-day Ghana from 1739 to 1749, writes in his 1760 text, A Reliable Account of the Coast of Guinea, that used Dutch slaaplakens were preferred to Danish ones, even though they were so thin that “you could almost blow to shreds, as you might a spider’s web.” An informant tells him that local women used them for menstrual rags.46

While the authors of European travel literature have much to say about the possible uses of linen in Africa, WIC documents reveal little. By taking a distant view of the data, however, we can learn something about local preferences. We learn, for example, that slaaplakens are consistently shipped to three African ports in our dataset—Ghana, Benin, and Angola—suggesting their value in each region. In the facturen, slaaplakens are rarely described, and when they are, modifiers are limited to “big,” “small,” “printed,” and “old.” The price of slaaplakens varies little over the course of twenty-five years, holding steady at around sixteen stuivers per piece for the most part. “Printed” slaaplakens are valued at 1.5 guilders, but there does not seem to be much of a market for them, since they are shipped in 1704 and then never sent again. Aggregating these data enables us to ask new questions about how and why different styles of European bedsheets circulated in an African context. As this project progresses, we will contribute additional context and data to the Dutch textile trade.

The Woven Record: Extant Textiles and Loss

Although archival descriptions are typically quite brief, these written accounts can sometimes be supplemented with extant textile samples or clothing. This is most often the case with garments that belonged to elite patrons, such as the eighteenth-century chintz robe (japonse rok) (fig. 8) in the Victoria and Albert Museum or the fashionable woman’s jacket (fig. 9) in the Rijksmuseum, both of which were assembled in the Netherlands with chintz produced on the Coromandel Coast in India. Chintz, or kalamkari,47 is a case in point: this textile is represented in many museum collections today, as noted in the contribution to this issue by Chris Nierstrasz.48 Garments and furnishings featuring chintz became the height of fashion across Europe, and the effort to imitate and then speed up the processing of textiles like chintz would be the major driver of the Industrial Revolution in the later eighteenth century. While examples of its use by the lower classes are rare, they can be found, whereas elite examples abound. A number of scholars have studied the provenance and use of chintz across Europe and Asia, particularly Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis, Ruth Barnes, Sarah Fee, and John Guy. These studies are made possible by the continuous taste for chintz, manifest in generous collections holdings. As a result, chintz has eclipsed the study of all the other textiles, ranging from expensive to cheap, that constitute the bulk of trade textiles but have not survived in such quantity.

Although garments made from other trade textiles are harder to come by, some merchant swatch books do exist, providing valuable insight into what these textiles may have looked like and how to interpret brief archival descriptions—even if they give no hint as to how they were configured into garments. The swatch book carried on the De Vrouwe Maria Geertruida, which traveled from the Dutch Republic to the west coast of Africa in 1788, for example, is rich with material samples of Indian-made, patterned textiles like bejutapauts, roemaals, corroots, nickanees, gingham, and inlandtse (native) chintz, all of which make frequent appearance on WIC and VOC cargo lists (see figs. 2, 3). In its brevity, the text that labels each swatch echoes the descriptions of these same textiles in cargo lists, sometimes illuminating the meaning and sometimes complicating our understanding. For example, sample numbers 4 and 5 are two examples of bejutapauts. The blue bejutapauts (“Blaauwe bejutapause”) is in fact blue-and-white checked, while the red bejutapauts (“Roode ditto”) is red, white, and blue checked. Our tentative interpretation is that the bejutapauts appearing in the documents without a modifier are the blue-and-white type, while red is a variation indicating a deviation from the norm. In these rare examples where a material sample can be read alongside a documentary reference, these two types of data read in concert, aiding in the interpretation of the evidence.

Another source of samples are the requests (called eischen, order or demand) for export textiles; for example, in one from Canton, Dutch merchants order quantities, types, patterns, and colors of silks for clothing and furnishing, to be either procured from the Chinese market or commissioned from Chinese manufacturers (fig. 10).49 In this case, the emphasis is on the colors of the silks, providing us with clear names for a range of hues and shades, which have not faded from use, as they have been tucked away out of light in the archives. These records include a wealth of textile samples that need to be examined more closely.

Gingham is a case where the material record complicates our understanding.50 A textile that is familiar today, gingham appears throughout historical documents and in historical and contemporary glossaries. Today, we know gingham as a two-colored textile woven in a balanced check pattern, the weave creating squares, typically in red and white or blue and white, but also in other color combinations. In the past, this term referred to a textile with a broader array of appearances. According to secondary sources, gingham had a woven pattern of stripes or checks. Historical gingham is sometimes described as having a texture, either from mixed fibers (cotton and wild tussur or muga silk) or from doubled threads in the warp and weft.51 The Dutch Textile Trade Project dataset from 1700 to 1724 shows a staggering range of additional terms to describe this textile, although they do not correspond to glossary definitions. Most strikingly, a number of gingham cargos are described as bleached or plain (effen), begging the question of what would make a plain white cloth register as gingham among the many white textiles circulating in this trade. Further, gingham is one of several textiles with a number of descriptors which we cannot yet fully define: sestienes, pinasse, taffachelas, and the translatable but still unclear mattress ticking (beddentijk) and underclothes (onderbroeken).

Thankfully, historical archives have yielded several examples labeled in a contemporary hand as gingham, providing insight about what this cloth was to European merchants from approximately 1720 to 1820.52 Four examples relate to the textile trade in West Africa. Two 1720 samples, both labeled “gingang,” have blue, white, and red woven stripes and are of cotton (figs. 11, 12).53 One has a white stripe running perpendicular, so this could be a checked cloth, or perhaps this piece includes part of a contrary-colored edge. The 1727 examples are two different types: “cutslies or ordinair gingang” (ordinary gingham) and “bombay stuff or silke gingang” (silk gingham) (figs. 13, 14).54 The ordinary example is blue with a repeat of three narrow white stripes. The silk gingham is dark blue with narrow white and yellow stripes.55 While in each of these four cases, additional text is provided with the samples, the terminology from the Dutch Textile Trade Project dataset does not match the language accompanying the samples, so we have no additional clarification.

In two later examples, we are either seeing entirely different types of gingham or are seeing the change in what this textile name meant decades later. The 1788 example is labeled “France gingans van Pondicherij”56 (fig. 15). This example is very different from the 1720s examples: the swatch has irregularly spaced white and blue stripes, with a blue-and-white ikat stripe interspersed.57 The 1820s example is closer to today’s gingham: a repeating check pattern of red and white, although it is formed from stripes of varying widths (fig. 16). The label includes the provenance: purchased in London. Vibe Maria Martens’s analysis suggests that it was handspun and handwoven in India, although at that date European machine-spun and -woven cottons were also circulating.58 While only one of the six samples is specifically labeled as coming from India, the others are most likely Indian gingham as well, but we should allow for a slight possibility that some could be European imitations.

In the case of gingham, then, material evidence that we can visually and physically examine today both challenges the received knowledge about this textile and provides a tangible dimension to the unclear terminology in historical documents. Each of these samples is both material and document, existing as they do within letters and books and with a pasted-on label, demonstrating a clear contemporary view of what they are. It is unfortunate that this evidence does not clarify the dataset and instead adds additional problems of interpretation, an important lesson of why we should not over-tidy data or rely on secondary sources that may reflect only a moment in the evolution of a given cloth. As the dataset grows and we add additional years of data, we are hopeful that a distant read will reveal patterns that bring some clarity or show clear change over time for textiles like gingham that show so much variety.

The Visual Record: Images and Social Context

This project grew from a desire to gain a greater understanding of how representations of textiles generated meaning in early modern Dutch paintings, prints, and drawings, especially images produced in the wake of global trade. While archival documents and extant material samples can help to determine the appearance, quality, circulation patterns, and monetary values of textiles, these sources are less helpful in understanding how textiles generated social meaning in the different geographies in which they circulated.59 In this section, we examine a few of the images that inspired this project, case studies that highlight how painted, printed, and drawn representations of garments—in conjunction with archival and material evidence—can shed light on the multivalency of textiles in the early modern global world. It is critical to concede, however, that the images discussed in this section were made by European artists, which means they are couched in an iconographical tradition that places Europe at the top of a self-generated ideological hierarchy. Instead of reinforcing these hierarchies, we read against the grain of these Eurocentric images by refocusing our attention on the deeply intercultural material histories of the textiles represented in them, which mediated social relationships both outside and inside the limits of colonialist iconographies.

Albert Eckhout’s African Woman and African Man

In the 1640s, the Dutch artist Albert Eckhout (1610–1655)—court painter to Johan Maurits, Governor-General of Dutch Brazil between 1637 and 1644—painted a series of eight life-size figures depicting the people with whom the Dutch had contact during their occupancy of northeastern Brazil in the second quarter of the seventeenth century (figs. 17 and 18).60 In 1654, these paintings were presented by Johan Maurits as a diplomatic gift to Danish King Frederik III and subsequently housed in his kunstkammer in Copenhagen. Striking in their life-size dimensions, the paintings in Albert Eckhout’s Copenhagen series are often understood as complex negotiations of visual and material culture that combine realistic renderings of flora, fauna, and artifacts with conventions of European portraiture.61 The attributes assigned to these figures help the viewer to identify their place in a hierarchy based on European conceptions of civility, the order of which—it has generally been agreed—is as follows, beginning with the least civilized: Tapuya, Brasilianen, African, and Mulatto/Mameluke, the names the Dutch and Portuguese used to denote people of mixed race.62 The garments worn by the figures in Eckhout’s series have traditionally played an important role in signaling each group’s place within this hierarchy: the Tapuya pair are covered with only the slightest foliage and string; the Brasilianen pair wear a simple white fabric, perhaps linen; the African pair wear what appears to be a loom-patterned blue-and-white–striped fabric; and the Mulatto and Mameluke pair wear sewn, rather than wrapped, white garments.63

Traditionally, the blue-and-white garments worn by Eckhout’s painted African woman and man have been classified as “African cloth”—which is a vague and somewhat meaningless designation when considered within the context of Africa’s vibrant textile industry, discussed in greater detail below. Is it possible, however, that Eckhout meant to represent a trade textile, rather than an African-made textile? If so, Eckhout’s painted representation shares many characteristics with a textile called guinea cloth,64 often described simply as guinees in WIC and VOC documents. The term “guinea cloth” refers to a category of Indian-made cotton cloths that varied in color, pattern, and quality. While company documents usually describe them only by color, extant samples and secondary sources suggest that they could be striped or checked (patterns woven on the loom from dyed yarns), or solid colored (woven and then piece-dyed) (fig. 19). Guinea cloths could be piece-dyed, bleached or raw, fine or coarse, which suggests they could be modified to accommodate different markets. Guinees shipped to Africa were usually relatively inexpensive: one piece of guinea cloth, which could range in size from thirty-five to fifty meters, cost between twenty and twenty-five guilders per piece on average, or about six stuivers per meter.65

The name “guinea cloth” suggests that these textiles were meant to be traded only in West Africa, a region that Europeans referred to as the “Guinea Coast” in the early modern period. Indeed, between 1700 and 1724, the WIC shipped more than four thousand pieces of guinea cloth to Mauritania, Ghana, and Benin, and an additional ten thousand to Angola. Blue-and-white cloths became so popular and so essential to trade that knockoffs were made: the Zeeland Archives in Middelburg houses a 1753 letter from a textile trader that included two types of blue-and-white cloths, one labeled oostindische, or East Indian—an indication of its “authentic” Asian provenance—and one labeled nagemaakte, or counterfeit (fig. 20).66

For early modern Europeans, the association of blue-and-white cloth with people from the African continent was pervasive in both travel literature and art, representing a type of social categorization whereby textiles and geography were closely intertwined. An early seventeenth-century visitor to Senegal, for example, wrote about seeing people wearing cotton robes “full of blue stripes, like feather bed tykes.”67 In 1602 Pieter de Marees similarly described the cotton shirts worn by “those in authority” as having “blue stripes, like ticking.”68 Olfert Dapper (1636–1689), on the other hand, although he had never been to Africa himself, nevertheless described a blue-and-white cloth that was woven in Benin, and other visitors describe similar cloths.69 For these Europeans, then, the patterns they reported seeing in Africa may have resembled the bedding in the background of Esaias Boursse’s 1656 painting Interior with Woman Cooking in the Wallace Collection (fig. 21) or a miniature pillow made for a dollhouse (fig. 22). Images from Dutch Brazil, like Eckhout’s African Woman and African Man, reinforced this association between blue-and-white cloth and Africa by the frequency with which enslaved Africans are depicted wearing blue-and-white–striped or checked garments.

As Colleen Kriger and others have demonstrated, the European merchants who shipped blue-and-white textiles to the west coast of Africa were responding to a preexisting preference for these loom-patterned garments, which went back to at least the tenth century.70 The association of blue-and-white garments with enslavement in European visual imagery, therefore, reveals the desire to reinforce visually the status of the people they enslaved rather than the social importance these textiles had to the local communities in which they circulated. Cécile Fromont has shown how the Kongo elite “reinvented notions and expressions of prestige in the new Atlantic context” through the acquisition of foreign objects and textiles—especially blue-and-white textiles acquired through foreign trade.71 Danielle Skeehan has likewise shown how guinea cloths circulating in the Caribbean acted as “material texts” for women and that these textiles were critical for articulating complex social identities.72 Interestingly, Liza Oliver has demonstrated that there was also a market for guinea cloths in Europe, which our data supports: between 1700 and 1724, nearly six hundred thousand pieces of guinea cloth—of various colors and qualities—were shipped to the Netherlands, but only about fourteen thousand were repackaged and sent to West Africa and Angola, suggesting that a large quantity continued to circulate in Europe.73 As Eckhout’s Brazilian paintings demonstrate, firm identifications of painted textiles are challenging, but we would argue that this complexity is truly representative of the trade itself, which was fueled by broad geographic movement, imitations, substitutions, and local adaptations.

Andries Beeckman’s The Castle of Batavia

Economic and material data can also shed light on images from Batavia, where complex sumptuary laws created sartorial hierarchies on paper that were repeatedly contradicted, challenged, or ignored in practice and images.74 Andries Beeckman’s The Castle of Batavia has long provided evidence of how garments created a visibly stratified community (fig. 23). Beeckman was a VOC soldier and artist who traveled to multiple locations in the Dutch East Indies in the 1650s and certainly spent significant time in Batavia. He produced watercolors of figures, animals, and landscapes, which also exist in anonymous copies and artworks clearly drawing from Beeckman’s originals. His best-known painting was made in Amsterdam after his return home and displayed in the VOC headquarters from 1662 until it was acquired by the Rijksmuseum in 1859. He populated the market scene in the foreground with figures from his watercolors, and a distant view of Batavia’s fort and city architecture provided the impetus for the title.

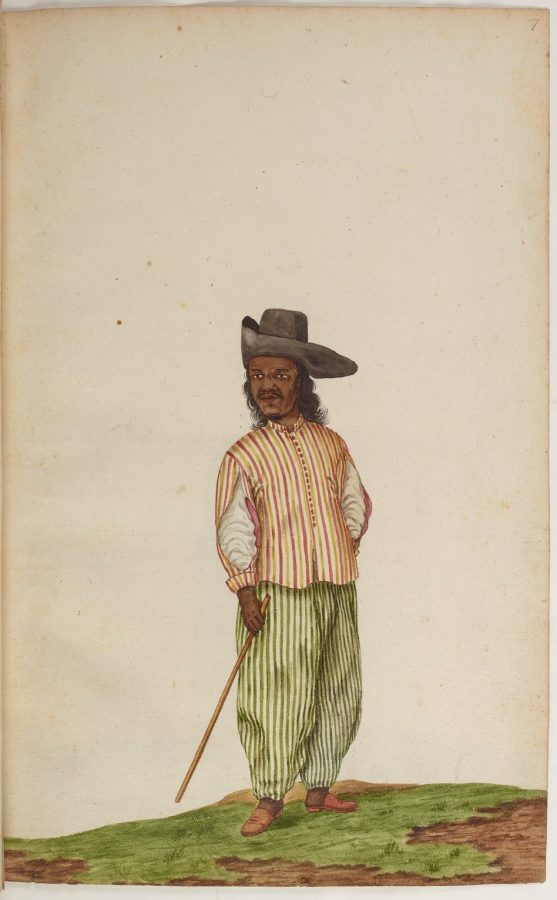

The painting is replete with examples of the ways in which garments can signify ethnic origins and social status: the Dutch merchant in European dress, walking with his Eurasian wife wearing a wrapped chintz skirt, and their servant shading them with a parasol; a number of women in white blouses and blue-and-white–checked skirts; and Chinese merchants in long robes (figs. 24, 25, 26). Here we will focus on the man in the right-center foreground wearing a hat; an orange-, yellow-, and white–striped shirt; blue-and-white–striped pants; and red shoes (fig. 27). This figure has traditionally been identified as a mardijker, a Dutch term that derives from the Portuguese mardicas, meaning free people. Mardijkers were formerly enslaved, or descendants of those formerly enslaved, from Portuguese-occupied regions of India and Bengal. Mardijkers in Batavia lived throughout the city (unlike many other ethnic/social groups, who had designated neighborhoods), generally spoke Portuguese, and were nominally Catholic. Contemporaneous accounts found their garments worthy of description, especially the striped fabric from which they were made. Johannes Nieuhof, for example, described the clothing of the mardijkers as “mostly in the Dutch style” but made with striped fabric and open sleeves with pants that go all the way down to the ankles.75 One hundred years later, Dutch travel writer Jacob Haafner wrote in a posthumously published text that the “Black Portuguese” wear “the richest clothing, with ruffles at their wrists, but bare feet, wandering along the streets with neither shoes nor stockings.”76 The mardijker pictured in Nieuhof’s book (fig. 28), derived from Beeckman’s watercolor (fig. 29), conspicuously wears shoes and stockings—which Frederik de Haan, in his much later account celebrating three hundred years since Batavia’s founding, described as typical of mardijker costuming.77

These three written descriptions of mardijker attire demonstrate both similarities and differences—the most notable discrepancy being Haafner’s nineteenth-century commentary about bare feet—which are likely a reflection of the three different centuries in which they were published, among other factors. The images—Beeckman’s watercolor, The Castle of Batavia, and Nieuhof’s engraving—are nearly identical, owing to the fact that they are all based on Beeckman’s in-situ preparatory watercolor. While Beeckman’s watercolor depicts the mardijker’s trousers with green stripes, this figure’s trousers in his painted view and later copies by other artists have blue-and-white stripes. Our analysis of the garments worn by mardijkers will focus on these three images, while also acknowledging—critically—that they represent the perspective of a single Dutch artist employed by the VOC who spent only four years in Batavia. With these qualifications in mind, how can we connect Beeckman’s images of mardijker attire to the incredible variety of textiles moving in and out of Batavia?

While there seems to be some confusion on what, precisely, was worn by Batavian mardijkers, the clothing issued to enslaved men by the VOC is clearly articulated in the documents: twice a year they were given blue-and-white–striped trousers.78 Given the similarities between the garments issued to enslaved men and the appearance of the trousers of the mardijkers in the three images discussed above, one wonders if Beeckman conflated the appearance of the VOC-issued clothing with the dress of the mardijkers in order to impress upon the viewer their formerly enslaved status. Alternatively, Beeckman may not have been aware of these sartorial distinctions. If this is the case, blue-and-white–striped garments must have been a fairly common signifier of enslaved status in Batavia, just as blue-and-white fabrics in West Africa and Brazil signaled enslavement for a European audience.

So what kind of textile was Beeckman referencing? One likely candidate is nickanees,79 an inexpensive blue-and-white–striped loom-patterned textile produced in the largest numbers in Gujarat at this time.80 We are fortunate to have a number of material samples of nickanees from swatch books—six in total (figs. 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). Recalling in some ways the striped gingham of figures 11 and 13, the nickanees have a repeating pattern of stripes of varying thickness. Noteworthy is the fact that in all but one case, the nickanees swatches are oriented so that the stripes run vertically, perhaps suggesting that this is the intended orientation when worn as a garment. There is also a remarkable similarity between the patterns of the blue-and-white vertical stripes, which are organized according to the following arrangement, with minor variations: a thick white stripe of eleven to twelve threads; a thick dark blue stripe of ten to twelve threads; a thin white stripe of two white threads; and a thick dark blue stripe of ten to twelve threads. Some swatches include an additional thin white stripe followed by a thick blue stripe. We have found one sample of nickanees from much later (1820s) with red stripes, which is labeled as “nicanees red,” whereas there is no color indicated on any of the other swatches (fig. 35). From this we have concluded that blue-and-white is the standard and red is a notable variation, as with bejutapauts.

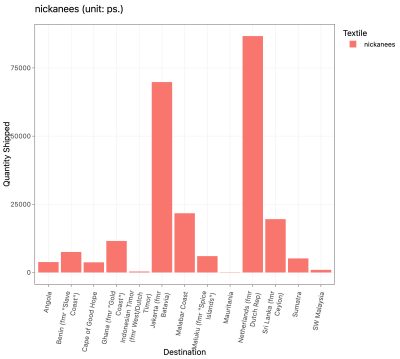

Like guinea cloth, nickanees were transported on both WIC and VOC ships during the years for which we have data, as the chart shows (fig. 36). Although secondary sources indicate that nickanees were popular in West Africa, they were also circulating in large quantities in Indonesia. In fact, almost seventy-five thousand pieces of nickanees were shipped to Batavia between 1700 and 1724. And while some of these cloths were indeed shipped back to the Netherlands, others remained in circulation in southeast Asia.

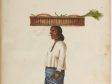

Jan Brandes’s Tea Visit in a European House in Batavia

The four women featured in Jan Brandes’s watercolor wear variations of the kebaya, a loose upper garment which is a staple of women’s dress across the Indonesian archipelago (fig. 37). This garment appears in many images of Batavian women—including Beeckman’s view of the city (figs. 23a, 25a), his watercolors of figures and the copies after these (figs. 5a, 38), Jan Brandes’s late eighteenth-century watercolors and sketches and Jacob Coeman’s portrait of the Cnoll family (fig. 39). This loose white blouse and its undetailed appearance in imagery might seem unremarkable, but these references to the kebaya, worn open in front (or buttoned or sewn shut) and sometimes sheer, reflect women’s dress in Batavia. Jan Brandes’s watercolor depicts variations on this garment (see fig. 37). From left, the gesturing darker-skinned woman, representing an Asian or Eurasian woman, wears a long kebaya with fitted sleeves, fastened at the top and spreading open over a loose, full skirt. The light-skinned European woman wears a similar kebaya, with a lace collar and cuffs, over a more structured gown. The dark-skinned serving woman, by contrast, wears a much simpler blouse, which falls only to her hips, over a wrapped skirt or sarong of red checks. If her status was not already clear by her serving tray, she also has visible bare feet. Race and skin tone are complicated in Batavia’s stratified society, where from the beginning of Dutch colonization, very few European women emigrated. Instead, Asian women bore future generations of the Eurasian populace of the city, as wives, mistresses, or enslaved servants of Dutchmen.81 While skin color did not always indicate a person’s status, dress and the many sumptuary laws regulating it assisted in the stratification of this colonial society; it was also a means for women to navigate among competing cultural forces.82

The generic white upper garment worn by the serving woman appears throughout images of women in Batavia, especially servants and enslaved women, and indicates a woman of simpler dress, modest means, and often lower status. Identifying a figure in an image as enslaved or free is a challenge, but when Caspar Schmalkalden copied Beeckman’s similarly dressed, barefoot woman (see fig. 38), he titled it “Eine Sclävin” (a slave); another copy also identifies this woman as enslaved.83 In Coeman’s portrait of the Cnoll family and their enslaved servants, the enslaved woman at right, again barefoot, wears the same white blouse over a wrapped skirt (see fig. 39).84

Beyond visually referencing cultural differences in dress, there is textual evidence of white shirts issued to women in Batavia. Miki Sigiura, writing on early examples of ready-made clothing, draws our attention to the 1750 regulations for supplying clothing to children and enslaved people in Batavia’s orphanage. These include specific mention of white or plain shirts of guinea cloth for enslaved women and for orphaned children, while enslaved men wore salempores, another plain, light cloth.85 If the shirts seen throughout Brandes’s and Beeckman’s images of women are readymade blouses, this in part explains their uniform appearance: the loose shape in the sleeves and waist, falling to the hips, with a slit at the neckline. This generic shirt is perhaps unisex, as some men in Beeckman’s The Castle of Batavia wear a similar garment.

Can we connect the 1750 regulation to imagery made in the 1660s and 1780s? Did the regulation codify a long-standing practice or introduce a new one? Can we read this shirt, like the blue-and-white textiles discussed above, as indicative of the free or enslaved status of these women, or is it a garment worn by many in Batavia, or the Dutch Indies more broadly? Finally, can we connect a loose white garment to a specific textile in the dataset? The 1750 regulation specifically indicated that enslaved women would wear a white guinea cloth shirt, which suggests a connection between that specific textile and their status. Blue-and-white guinea cloth, as we saw above, is connected to both the Africa trade and the perception of enslaved status. But where does white guinea cloth come in? Our dataset shows that 45 percent of all guinea cloth circulating in the VOC and WIC networks between the years 1700 and 1724 was white, not the blue-and-white variety discussed above. Of these white guinees, less than 10 percent were destined for the west coast of Africa. Forty-two percent of these white cloths were shipped to the Dutch Republic; about 30 percent were traded to various locales in Southeast Asia; 8 percent to Japan; 4 percent to South America (Essequibo); and the remainder to other Indian Ocean markets, demonstrating the differentiated markets for this subtype. While the people who purchased the white guinea cloth and sewed it into shirts for the orphans and enslaved women would have been aware of its texture and drape, which may indeed have differed from other white cloths circulating in this network, we, the viewers of these images, have no such insight. Guinea cloth here, in painted form, is not visually distinguishable from any other white cloth, ranging from high to low quality, from fine lightweight muslin86 or silk to coarse, sturdy cotton.87

What, indeed, differentiates the enslaved women’s shirts in see figs. 37, 38, and 39 from the billowing sails in Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom’s seascape (fig. 40)? Bleached and natural sail cloth,88 which was traded alongside many other textiles covered in this project, had an entirely different use and needed to be durable and strong to be effective.89 Again, sail cloth moved in staggering volume; approximately three to five million square meters of sailcloth (53 bales, 17,701.5 rolls, and 143,783 pieces) moved in VOC cargos between 1710 and 1715 alone. Utilitarian textiles like this rarely survive because they were used rather than collected—and the few remaining material samples of sail cloth from the Dutch early modern period are small and so removed from their context as to be virtually meaningless (fig. 41).

While images like Vroom’s enliven this textile, allowing us to see it put to use, textual references to sail cloth can provide a sense of their social purpose—including as clothing. Sigiura’s research on cheap readymade clothing is again helpful here: sail cloth is one of the textiles worn by enslaved people in Cape Colony and Batavia. Sugiura describes enslaved males in the Cape wearing doublets that were lined with cotton sailcloth.90 Used as a lining for a garment, the durable and rough white (or light-colored) textile would not be visible in imagery—but it might be reasonable to imagine this white garment lining the many striped doublets worn by men in Beeckman’s images of Batavia. Sail cloth was put to this purpose precisely to be durable but not comfortable, a reminder of the lower status of the enslaved men who were issued such garments. The implied texture of these white textiles—guinea cloth and sail cloth—is something we cannot understand from visual culture, only from material samples and brief descriptors in the textual data. However, considering these three types of evidence together enables a greater understanding of the use and meaning of these textiles in the early modern period.

The Visual Textile Glossary and Interactive Web Applications

iFrame of Dutch Textile Trade- Data Visualizations (https://dutchtextiletrade.org/data-visualization/)

As the above sections have shown, four different types of data (textual, material, visual, and quantitative) each contribute meaningfully to the picture of the Dutch Republic’s global trade in textiles, and when considered together they enable fuller interpretation of the incomplete record of this trade. Information drawn from the extensive records of the VOC and WIC shows quantities, geographical circulation, values, and types of textiles, as well as shorthand descriptions of textiles, illuminating patterns that can help us to better understand these records from a distance. When the information expands in temporal scope, it will enable extended analysis. The material record further contextualizes the data pulled from the archives, but it is scant and often lacking in context. Historic images can also assist in understanding how these textiles were used but must be interpreted carefully, since they are steeped in the prejudices and hierarchies of the cultures that produced them. The Dutch Textile Trade Project brings together these four kinds of evidence for the first time in an interactive Visual Textile Glossary91 so that they can be studied in conversation with one another.

Our Visual Textile Glossary debuts with twenty-five years of data drawn from Dutch archives (1700–1724) and ten textile terms out of the three hundred-plus that appear in the archival trace of this trade. We also include a broad range of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century images that feature trade textiles, as well as samples of the types of textiles traded on Dutch ships. Over the coming years, we will expand both the dataset and the Visual Textile Glossary incrementally until we encompass the full two centuries of extant Dutch trading documents. In the next phase of the project, we will also extend our coverage to include the Middelburgsche Commercie Compagnie (MCC) archives.

There are three primary pieces of the Dutch Textile Trade Project, all of which are available, open access, on the website: the dataset, the interactive data visualization applications, and the Visual Textile Glossary. From the user perspective, the Visual Textile Glossary is the starting point. The point of entry for each term is two paired images: a historical image that shows the textile in use, typically worn as a garment, and an existing sample of the same (or similar) textile from a museum collection or archival swatch book. These images are interactive and, as appropriate, include annotations. We then provide a short definition of the textile type, which includes spelling variations, and a brief list of related textiles, when possible. Below this basic information is the “Textiles, Modifiers, and Values” application, fed by the project dataset, where users can explore a given textile type in greater detail. For example, the interactive bar chart allows users to visualize the quantities of imported or exported textiles over time or across geographies. It is also possible to compare different types (modifiers) of a given textile. For example, a user could compare the average price of gold baftas (sturdy cotton cloth) shipped to Java against those shipped to Jakarta, or a user might compare the average prices of different-colored baftas over time. In short, the interactivity of the application allows users to ask their own questions of the data. Below the web application is an expository essay that expands on the brief definition offered at the beginning of the entry. Each essay features current research on the featured textile, which draws from archival data, extant material samples, early modern images, and secondary literature. Additional visual and material examples, beyond the pair that opens the entry, are available throughout the essay and in the frame below.

iFrame of Dutch Textile Trade- Textiles, Modifiers and Values App (https://dutchtextiletrade.org/projects/textiles-modifiers-and-values/)

In addition to the “Textiles, Modifiers, and Values” application, the Dutch Textile Trade Project website also features a “Textile Geographies” application, which lets users view textile data using geographic and infographic visualizations (explore further in the iframe below). One of the great strengths of this application is that it enables users to search the project’s entire textile dataset by a range of archival modifiers—including color, pattern, process, fiber, or quality—in addition to historic textile names. For researchers who seek to identify or learn more about textiles represented in images, having visual descriptions (blue, checked, striped) as a point of entry to the dataset is critical, because textile names are not self-evident in images, as demonstrated in the preceding section. Being able to search by modifiers also enables users to see patterns over geographic space. For example, searching by the color “blue” yields a map showing the concentrations of blue textiles—both their total quantities by piece and their values in guilders—in VOC- or WIC-occupied areas. Such maps can shed light on local patterns of consumption, shifting the focus from company merchants to local residents and drawing attention to the agency of consumers.

iFrame of Dutch Textile Trade- Textile Geographies App (https://dutchtextiletrade.org/projects/textile-geographies/)

The dataset that underlies the site is available for download as a comma-separated values, or CSV, file for further exploration. This dataset provides information about each shipment of a textile on a ship, including the following variables: document source, ship name, origin and destination locations and dates, textile name, quantity, modifiers (sorted into color, pattern, process, geography, quality, and other), the value of the ship’s cargo, the value of this specific textile, and the per-piece value. In order to make these data usable for data visualization software and for researchers, we had to make choices to “tidy” the data so it is legible and comparable. This included some structural reorganization as well as standardization in spelling to account for the many variations used by Dutch clerks. As discussed earlier in this essay, our decision to work with Dutch currency to indicate value is deeply fraught. We also made difficult decisions about geographical terminology, balancing historic realities with recognizability to users today. The geographies of this project were and—in several cases—are contested by local people, as well as colonial and imperial powers. These places also have multiple names and spellings across languages, which are not simply benign spelling variations but are indicative of ongoing shifts in power dynamics. These were not decisions we took lightly, and we recognize that, in some cases, our choices may be flawed. On the website we provide more detail about our collaborative decision-making process,92 and we welcome feedback and suggestions for improvements.