This essay explores the circulation of the japonse zijde rok, a popular ready-made garment that initially came to the Dutch Republic from Japan via the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and was much sought after by European elites. The study of these rare and expensive robes has been complicated by the fact that a variety of names are used to describe the same or similar garment types, some of which have different points of origin and may even be made from different materials, which the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data and web applications has helped to clarify. This essay also shows how the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s open-access data can be used for quantitative research inquiries and to create independent data visualizations.

Assisted by modern forms of transportation, today many textiles—and the garments made from them—easily circulate the globe, oftentimes to the detriment of our environment.1 However, the interconnectedness of today’s billion-dollar fast-fashion industry is not a modern phenomenon but instead has its roots in the early modern period. From the seventeenth century onward, the Dutch East and West India Companies (VOC and WIC, respectively) played a major role in expanding textile trade networks on a global scale.2 Ready-made garments were among the variety of traded textile goods, and none were more sought-after in the Dutch Republic than the so-called japonse zijde rok, a Japanese silk robe or kosode that was as highly priced as it was popular.3 This item signified the Dutch Republic’s exclusive trade relations with Japan and demonstrated the growing taste for Asian imports at the time.4

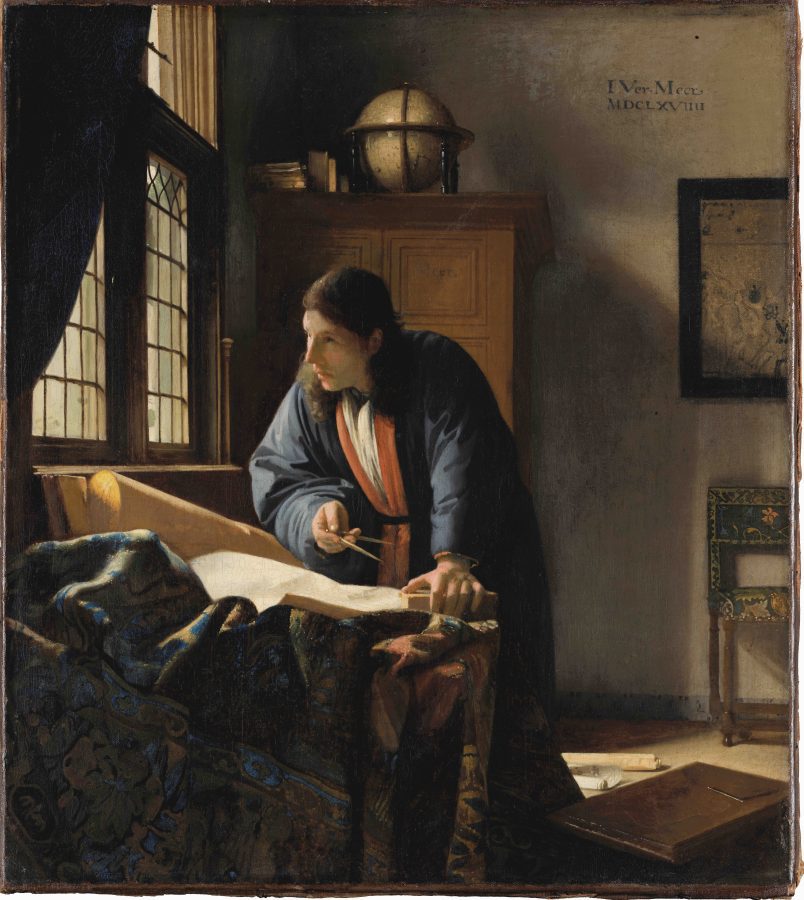

One of the few surviving gowns made in Japan for export is today part of the Newhailes collection in Scotland (figs. 1 and 2). This padded kimono-style garment was made according to Western tastes, which required larger proportions and favored a purely decorative arrangement of patterning. The blue silk—which includes Japanese parsley motifs and curious fake family crests—was woven, dyed, and stitched together in Japan before being shipped to a Western market.5 Few robes were intended for export,6 highlighting their preciousness. Compared to robes made for the domestic Japanese market, export robes are typically floor length, have wide sleeves, and are heavily padded, among other modifications. Many preserved export garments are made from colorful fabrics with eye-catching patterns, suggesting that European consumers preferred more conspicuous styles.

As the rarity of the above example demonstrates, working on early modern textiles and garments often means studying just a small number of objects that have survived up to the present day. Access to these often-fragile objects can be limited, making scholars dependent on the digitization efforts of museums and other cultural institutions. In light of these obstacles, researchers must often rely on other sources, such as visual or written evidence. By bringing together visual, sartorial, and written evidence in one digital space, the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s website and applications offer new interpretive possibilities that can contribute to our understanding of historical textiles. In particular, the project’s interactive web applications allow for user-directed exploration of the quantitative dimensions of the Dutch global textile trade.7 In this essay, I will demonstrate the benefits of such an approach by focusing on the study of japonse zijde rok. I will focus on the following questions: To what extent can these web applications clarify the relationship between the representation of textiles in painted images and the textiles themselves? How can these aggregated data help researchers link archival descriptions of textile names to the actual textiles in question? And, specific to the japonse zijde rok, when production locations shifted toward the end of the seventeenth century, did the geographical descriptions of these robes also change? What can the dataset tell us about the increasing demand for japonse zijde rokken? What kind of quantitative and qualitative conclusions can we make from the dataset?

Picturing the Japonse Rok

The question of whether paintings are a reliable source of information for historical costumes and textiles is a matter of constant debate among scholars.8 Although it is rarely the case that an extant garment can be linked directly to a work of art, some scholars mistake pictorial representation for material reality, overlooking possible interventions by the artist or patron. Other researchers, however, have used a combination of materialist and art-historical methodologies to treat costume and dress as important carriers of meaning.9 These scholars have made significant contributions to our understanding of the often-neglected relationship between garments and their representation by using a wide variety of sources to contextualize the visual material.

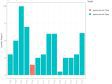

Painted garments can reveal contemporary tastes for certain styles or fabrics from a particular geographical region. This is evident in paintings from the Dutch Republic, where Japanese-styled robes started to appear in genre scenes and portraiture from around the mid-seventeenth century.10 By the end of the century, the japonse rok was not only a popular status symbol for wealthy commissioners but also an attribute for images of scholars and a mechanism for artists’ self-fashioning.11 Probably the best-known depiction of this novel garment is in Johannes Vermeer’s The Geographer (fig. 3). The male figure’s attributes identify him as a scholar, engrossed in his survey work and wearing a comfortable-looking dark-blue robe, belted around the waist. The similarity to preserved garments like the one mentioned above (see fig. 1) invites a juxtaposition that can expand our knowledge of both media. The tradition of representing scholars and artists wearing Japanese-styled gowns continued into the eighteenth century, although the choice of this precious garment does not necessarily reflect the actual working attire of an artist, as Martha Hollander has argued.12 For instance, the portrait attributed to Aert Schouman (probably a self-portrait) shows the painter pausing at his easel (fig. 4). Dressed in a light brown robe with floral decoration, the pipe-smoking painter casually stares at the viewer, perhaps reflecting a preference for less formal self-fashioning. Researchers trying to connect a specific term or actual garment to such a representation are presented with a number of significant challenges, which the Dutch Textile Trade Project may help alleviate.

Japonse Zijde Rok: A Garment with Many Names

“Japonse zijde rok” is a seventeenth-century Dutch term for robes that initially arrived in the Dutch Republic aboard VOC ships from Japan.13 These precious silk robes were a gift to Dutch traders invited to the court of the Tokugawa Shogun in Edo (today’s Tokyo).14 At annual visits, the renewal of trade relations was followed by a gift-giving ceremony.15 This is the reason why they were also called schenkagierocken (gift gowns) and keyserrocken (imperial gowns).16 The term “japonse rok” appeared in VOC documents and other written sources, such as letters or inventories, in the second half of the seventeenth century in the Dutch Republic. By 1700, various names, such as chamberlouc, japon, nachtrok, nachttabbaard, and cambaay were used to describe the japonse rok.17 In secondary literature, the name “banyan” is sometimes used interchangeably with “japonse rok,” although recent research suggests that it may have referred to a comparable fashion trend in England, where the term does not appear in published sources until the 1730s.18 Complicating matters, “banyan” could also refer to a similarly tailored garment produced in India but made from chintz, rather than silk.19 In short, the geographically derived descriptions attached to these garments by Dutch traders and merchants often signaled foreign gowns in a broad or generic sense and should thus be treated cautiously.

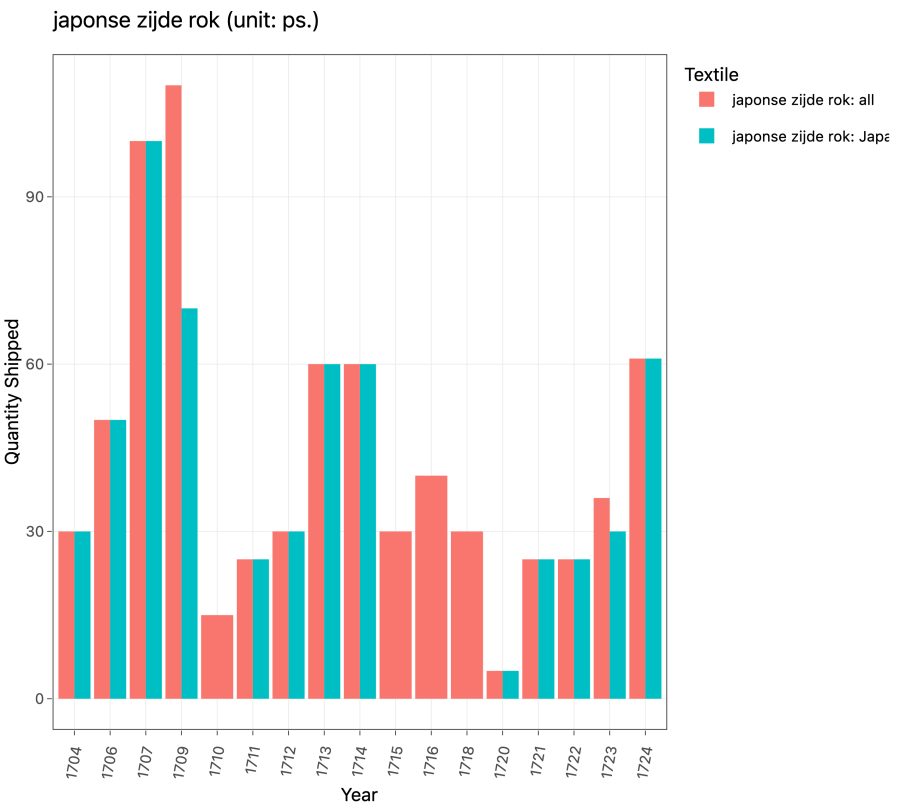

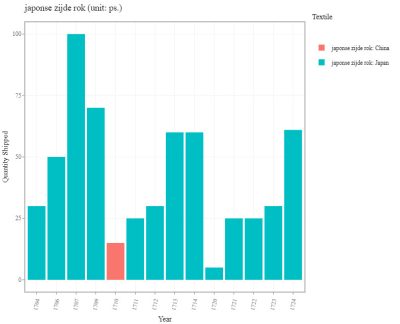

Data from the Dutch Textile Trade Project allow researchers to take a distant view of variations in textile naming conventions, which can help clarify contemporary usage. For example, the bar graph in figure 5 represents all the textiles described as japonse zijde rok in the dataset (shown in red). When the total number of japonse zijde rok is compared to those with the modifier “Japan” (shown in turquoise), it becomes clear that not all japonse zijde rokken were described with that geographical modifier “Japan.”20

In fact, as figure 6 shows, in 1710 a number of robes were described with the geographical modifier “China.” Japan and China are the only two geographical modifiers recorded in VOC records. Japonse rokken recorded on cargo lists from 1715, 1716, and 1718, as well as parts of 1709 and 1723, were assigned no geographical modifiers at all. The terms japon, rok, kleed, and mantel—which are present in the dataset as well—might also refer to japonse rokken, but it is impossible to be certain. Interestingly, selecting the term “japon”—which is often used interchangeably with “japonse rok”—yields some points of origin in Persia (with a total quantity of five hundred pieces) and the Malabar Coast in India (150 pieces). The term “banyan,” however, does not appear in the data during this period.

In the Dutch Republic, the high demand for this garment could not be met by Japanese exports alone.21 Not only did this demand stimulate the creation of domestic imitations made from imported textiles, but it also led the VOC from 1684 onward to order robes from India made of chintz.22 To see whether Japanese-styled kimonos produced elsewhere were still similarly described, the web applications of the Dutch Textile Trade Project offer helpful geographical information about the distribution of textile names. For the given time frame (1700–1724), the name japonse zijde rok was used for garments originating in the regions of Nagasaki (176), Batavia (281), and Ceylon (five), today’s Sri Lanka. Cargo data from this period suggest, however, that this name may have been used for other types of garments as well.

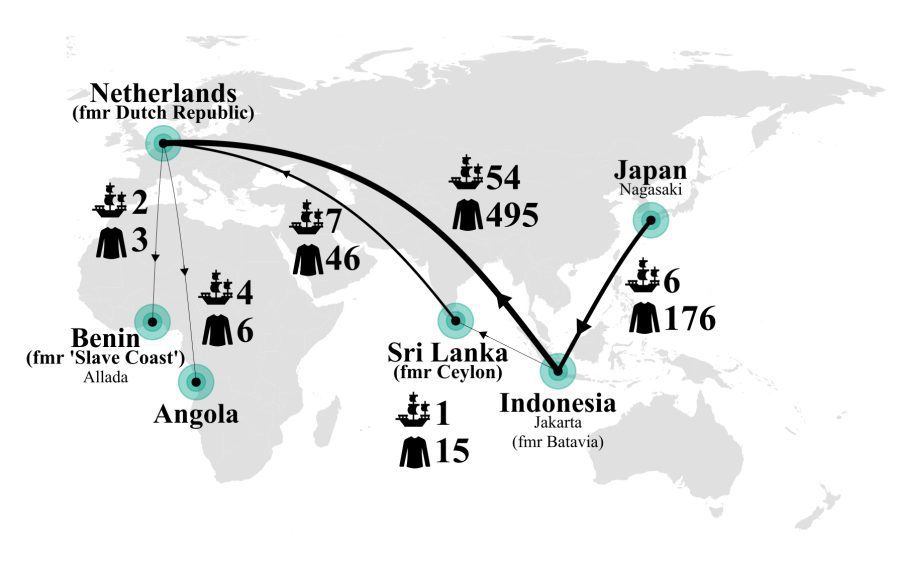

Figure 7 shows a map representing Dutch trade in japonse zijde rok between 1704 to 1724, based on the dataset.23 This map visualizes the trading ports, ship routes, number of shipments, and quantity of japonse zijde rok (by individual garment). A portion of these robes originate in Japan, where they were prepared for shipping at a factory in Deshima, an artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki.24 From there, all the shipments went to the VOC’s headquarters in Batavia, today’s Jakarta, before going on the homebound fleet. Interestingly, 495 pieces in total of japonse zijde rok were shipped from Batavia to the Dutch Republic, exceeding the number of items shipped from Japan by 319 pieces.

Figure 7 also shows the circulation of garments described as japonse zijde rokken in the VOC cargo lists. The fact that more textiles were documented at the VOC’s headquarters in Batavia than they received from Japan might have two explanations. One possibility is that stored items were shipped with a delay, although this seems unlikely due to the large difference in the number of textiles. More likely, I would argue, this discrepancy is an indication of additional garments produced elsewhere and described by other names. For instance, the term cabajen or cambayen, a finished robe made from chintz and produced in quantity in the Coromandel Coast in India,25 might be a different name for the same garment, which would have been renamed when packaged and shipped from Batavia. Further research on alternative production sites in India is needed, as it would help clarify the complexities of this global trading network.

The majority of the japonse zijde rok shipped by the VOC during this period were destined for the Dutch Republic, with the important exception of fifteen robes that were shipped to Ceylon from Batavia in 1710. During the same period, forty-six pieces in total went from Ceylon to the Dutch Republic, suggesting that additional garments were made on the model of imported japonse rokken or shipped in from elsewhere. Interestingly, japonse rokken also traveled on WIC ships from the Dutch Republic to current-day Benin (three) and Angola (six), where they were presented as gifts to the Angolan king, demonstrating the wide reach of VOC trade and the often-overlooked connections between VOC and WIC trade.26

The Dutch Textile Trade Project web applications also enable users to download the complete dataset as a comma-separated values (CSV) file, which provides even more detailed information for further investigation. For instance, these data suggest a decline in japonse zijde rok coming from Japan beginning in the eighteenth century. According to the dataset, between 1704 and 1724, six ships reached Batavia from Japan with a total of 176 pieces. While in 1707 the cargo contained fifty robes, the following shipments only had thirty and in 1723 only six. The decrease of Japanese exports of japonse zijde rokken during this period becomes more conspicuous when compared to cargoes from the seventeenth century chosen from secondary literature. In 1651, a ship leaving Japan had, among other items, two hundred Japanese silk robes as well as some silk wadding on board.27 In 1692, they received 123 gifted robes in total. Yet, depending on the mood of the Shogun, the number of gowns could change or even be eliminated entirely.28 Hollander has suggested that the decrease toward the end of the seventeenth century could also be connected to the already-established production of japonse rokken in the Dutch Republic.29 Trends like these are easily visible in the dataset without having to distill cargo entries from the abundance of literature. As the Dutch Textile Trade Project amasses more data from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, new patterns of trade are sure to emerge from the web applications, which will be an asset to researchers concerned with the global dimension of the Dutch textile trade, especially in light of the limited number of extant garments and textiles from this period.