Technological innovations and the 2020 global pandemic have increased scholarly interactions with and reliance on digital resources, leading cultural heritage institutions to prioritize initiatives that digitize and organize their collections online, aiding in their accessibility to a wider global audience. Focusing on the Montias Database of 17th Century Art Inventories, this article turns a critical eye toward digitized art-historical data that is collected, preserved, and organized by cultural heritage institutions. Using the digital art history project “Beyond ‘Exceptional’: Reassessing Women’s Participation in the Cultural Sphere of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam with Digital Social Network Analysis,” I demonstrate the potential of computational methods for mediating the biases inherent to these collections.

In 1997, Suzanne Keene published her foundational article addressing museums’ growing embrace of digital tools, notably the potential of a world-changing technology: the internet.1 Over two decades later, thanks in part to rapid advances in technology and a global pandemic, many cultural heritage institutions have embraced the potential of digital databases, prioritizing initiatives that make their vast and often hidden collections available to broader, virtual audiences. A growing number of museums, archives, and libraries have committed to providing free, unrestricted use of their online collections through open access.2 Several museums, including the Rijksmuseum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, have taken a step further by instigating collaborative projects that employ cutting-edge computational tools, notably artificial intelligence (AI), to investigate the growing body of data held in their online collections and databases.3 As scholarly reliance on digital resources continues to grow, new questions emerge on the relative neutrality of these repositories and the influence of the institutions and individuals who catalogue and steward them.4 Critically, scholars have noted that digitized data is not necessarily more equitable, and the accessibility of these resources is affected by a variety of social, economic, and political factors.5

This article begins with an overview of the Montias Database of 17th Century Art Inventories, drawing special attention to the sometimes unrecognized partiality of collected data and its subsequent organization. Through a brief discussion of the related digital art history project “Beyond ‘Exceptional’: Reassessing Women’s Participation in the Cultural Sphere of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam with Digital Social Network Analysis,” I demonstrate how computational methodologies can help mediate these biases while also optimizing searchability of and accessibility to these increasingly vital scholarly resources.

Like historical documents and art collections housed in brick-and-mortar archives and museums, digital databases are shaped by the individuals who created them and frequently reflect their aims and interests, whether conscious or not.6 This is evident in the Montias Database of 17th Century Dutch Art Inventories, one of the earliest computer databases containing art-historical information. The Montias Database was created by John Michael Montias (1928–2005), a professor of economics at Yale University who began his career studying Soviet-era economics.7 His initial inquiries into art history in the 1970s were driven by the broader shift in the field toward cultural economics in American and British universities, along with his personal love of art.8 Montias combined expansive archival work, statistics, and formal economic theory, a novel approach that led to new discoveries about notable Dutch artists, including Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675).9 His method underscored the value of inventories as a primary document for art-historical research and transformed the way art historians study artistic production and consumption.

Montias spent the 1980s and 1990s collecting and analyzing information related to seventeenth-century inventories housed in the Stadsarchief in Amsterdam, both independently and in collaboration with the Getty Research Institute.10 He carefully transcribed and collected information from 1,288 inventories housed in the archive and conducted additional archival research on prominent artists, dealers, and collectors he encountered in the records. He compiled his findings into two spreadsheets. One contained information related to the owners of the inventories, and the other included details about the objects listed in the documents, including object type, subject matter or material, attribution, location within the residence at the time of the inventory, and buyer’s name. The bulk of the inventories included in the Montias Database were drawn up by the Orphan Chamber of Amsterdam, which hosted public auctions.11 The remaining inventories consist of other auctions of goods, death inventories, prenuptial agreements, bankruptcy inventories, and documents relating to the movement of objects between individuals. In addition to publishing his research on the Amsterdam inventories in 2002, Montias gifted his “database” to the Frick Art Reference Library in New York (FARL).12 In consultation with Montias, the FARL staff, led by Louisa Wood Ruby, combined the two spreadsheets into one web-based version, and it was made available to the public at any institution that had a Star Database in 2001.13 In 2009, FARL launched a new web-based version (fig. 1) of the Montias Database, providing access to anyone with an internet connection.14

Although Montias focused on artists, artisans, and their milieu, his methodical approach to archival research also yielded information related to the lives of the local population of Amsterdam. Rather than an exhaustive record of all inventories in the city during this period, the inventories included were carefully selected by Montias based on a set of criteria he developed in consultation with the Getty, including the artworks they contained, the prominence of the inventory’s owner, and their relevance to his own research, making them a useful but limited subset for early modern researchers. While scholars have utilized the Montias Database to ask questions related to painters and collectors, individual paintings, and painting genres, there is a wealth of information beyond painting waiting to be uncovered in these data.15 For example, the Montias Database includes a variety of textiles, which were listed alongside the paintings that were Montias’s focus—to choose but one example related to the content of this special issue.

Montias’s innovative socioeconomic approach and his focus on auctions held by the Orphan Chamber allowed for the inclusion of individuals from different economic backgrounds and occupations. Through the cultivation of his database, he sought to provide vast amounts of archival information related to the various roles of auction sales, collectors, and dealers in the Amsterdam art market in an easily digestible manner for art historians to include in their own analyses. Although Montias did not organize his database to answer questions related to identity beyond religion and occupation, his commentary on each inventory is filled with insightful details gleaned from the inventories and additional archival work, including notes on individuals’ relationships and momentous milestones in their lives, such as marriages, births, and deaths. This dataset, while focused on the creation and movement of visual and material culture, is representative not just of the upper echelons of Dutch bourgeois society but also of a wider swath of the community who interacted on varying levels with the consumption, sale, and creation of fine art and material culture in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.

Due to the constraints of the gift, FARL cannot ‘clean’ or edit— remove, correct, or add information—the data housed in the current web interface.16 Although the Montias Database stands out as an unusual case among art-historical computer databases, many museum databases and online collections are similarly structured in a way that limits their searchability to a few parameters decided by the online repository’s creator(s). It is often difficult to ascertain the details surrounding an institutional database’s creation, particularly for larger endeavors that span several years and involve numerous participants. And yet these factors are critical to consider, as recent studies have demonstrated that systemic bias is present in a wide range of digitized collections.17 As many institutions’ online collections were designed to be searchable only through a restricted web interface, their structure places limitations on the ways in which scholars can engage with the data they house. Restricted searching capabilities also impact researchers’ ability to overcome these biases and fully interrogate the digital data in a comprehensive, efficient, and unimpeded manner. In 2019, to optimize the searchability of the Montias Database, the FARL, made CSV (comma-separated values) files of the Montias Database publicly and freely available on GitHub, an online software development platform that allows users to store and collaborate on digital projects.18 The flexibility of CSV files allows researchers to expand, revise, and update Montias’s original dataset on their personal devices so that it can better respond to a broader set of questions related to the production, consumption, display, and sale of fine art and material culture in seventeenth-century Amsterdam. The original conception of the Montias Database—and the scholarly arguments that shaped it—has been faithfully preserved by the FARL in these spreadsheets.

The digital documents form the foundation of my initial Frick digital art history fellowship project, “Beyond ‘Exceptional’: Reassessing Women’s Participation in the Cultural Sphere of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam with Digital Social Network Analysis.” Focusing on inventories dating to the 1630s, the project applies network analysis using Python, a standard programming language, and the NetworkX suite of Python tools to illuminate individual women and trends related to the consumption and creation of fine art and material culture that were obscured by Montias’s organization of the inventories. Network analysis is a broad, inclusive approach for assessing agency by visualizing networks that represent individuals as “nodes” and connections between those individuals as “edges.” Netherlandish art scholars and collaborations, namely Hans van Miegroet, Matthew D. Lincoln, and Project Cornelia (University of Leuven), have utilized network analysis to examine art markets, print and tapestry production, and workshop practices.19 Some of these projects, notably Project Cornelia, investigate gender as a part of their broader initiative. The individuals in this study are collectors, makers, sellers, or institutions from inventories dated to the 1630s in the Montias Database. In addition to illuminating individual women and trends, this project interrogates the inequities imposed by early modern gender norms. The 1630s are an optimal starting point because of the simultaneous rise in artistic and mercantile activity during during this decade. The incorporation of the Dutch East and West India Companies, in 1602 and 1621 respectively, led to an influx of wealth and imported materials and objects, such as Chinese porcelain, spices, and naturalia into Amsterdam. The port city was also an essential hub for artists, artisans, collectors, and art dealers. Prominent art-historical figures who appear in the 1630s network include Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), who relocated to the port city from Leiden around 1631, and ebony worker Herman Doomer (ca. 1595–1650), who created luxurious furniture pieces such as the cupboard in figure 2, embellished with imported ebony and scintillating mother of pearl.

Women do occasionally appear as inventory owners in the Montias Database. A notable example is Susanna Ruts (1598–1649), whose 1636 inventory includes a portrait of her father, Nicolaes Ruts (1573–1638) (fig. 3) by Rembrandt that is now housed at the Frick Collection.20 However, there are several instances where Montias has indicated the male spouse as the inventory’s sole or primary owner. By carefully analyzing Montias’s translations, his Dutch transcriptions, and the original document (when possible), these listings were reorganized to reflect the correct inventory owner(s) in the CSV files, returning dozens of women to their rightful role of owner and illuminating a diverse set of shared inventories that range from prenuptial to a range of different types of exchanges of goods. Individuals mentioned in Montias’s commentary who do not have inventories in the database were also incorporated to further supplement the dataset. For example, in the commentary of the 1637 death inventory of Emanuel van Baseroode, which details goods held in common with Janneken Willems, Montias includes information about the 1669 death inventory of their daughter, Anna van Basserode.21 Montias notes that this inventory included several works by Rembrandt, Jan Lievens, Hercules Seghers, and Philips de Koninck.22 Paintings by these artists are not found in Van Baseroode’s and Willems’s earlier inventory, suggesting Anna van Basserode acquired them later in life. Further research is necessary to determine if this was an independent or joint venture with one of her two husbands, Francois de Coster III or Anthonie van Beaumont.23 The inclusion of individuals and objects mentioned in Montias’s commentary expands the scope of his original dataset, further enriching the project.

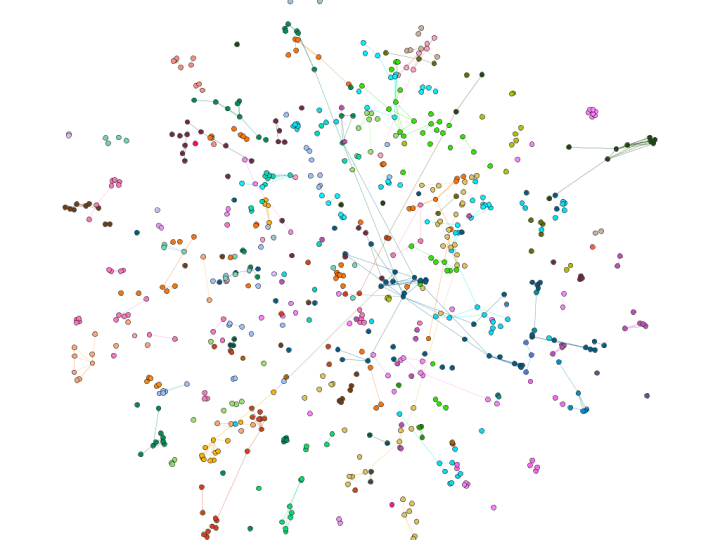

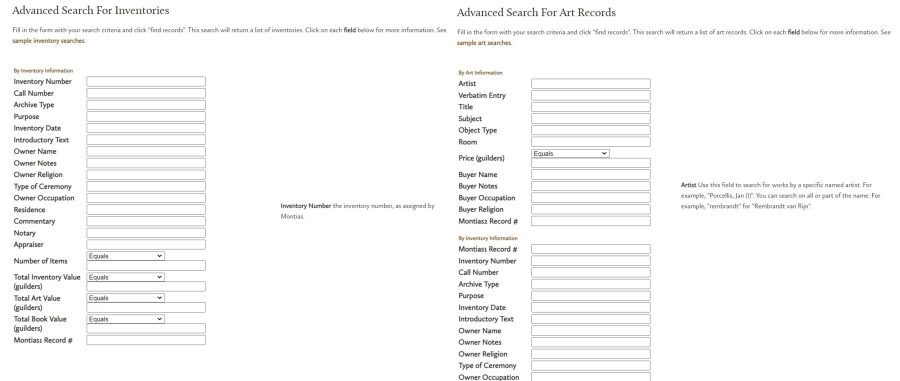

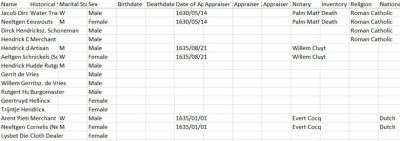

To create the network, pertinent information from the 168 inventories in the Montias Database dated to the 1630s were meticulously transcribed into two new CSV files. The first contains information related to the inventory owners and other individuals listed in Montias’s commentary, who become nodes in the network (fig. 4), and the other lists the connections (or edges) between two nodes (fig. 5). In addition to correcting inventory owners’ information and pulling data from Montias’s commentaries, categories of data were created in the files so that the information can be filtered by an individual’s sex, marital status at the time of the inventory, and nationality. In total, twenty-seven new data categories were added to the files to support a variety of research interests beyond the sex of the individual. The network created from these CSV files were analyzed in Python using code adapted from John R. Ladd, Jessica Otis, Christopher N. Warren, and Scott Weingart.24 Also with Python, a graph file was created from the nodes and edges within the CSV files that can be used with Gephi, an open-source network analysis and visualization software, to further analyze and visualize the network. The network visualized by Gephi (fig. 6) depicts the entire 1630s network, which contains 2,234 nodes and 4,915 edges. The network contains forty-eight distinct clusters or groups, distinguished by color. The clusters of closely linked nodes were detected in Gephi based on the node’s modularity class with a resolution of 1.

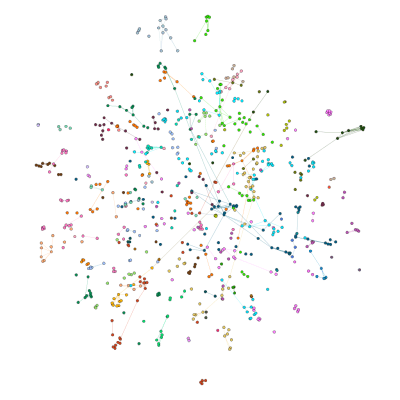

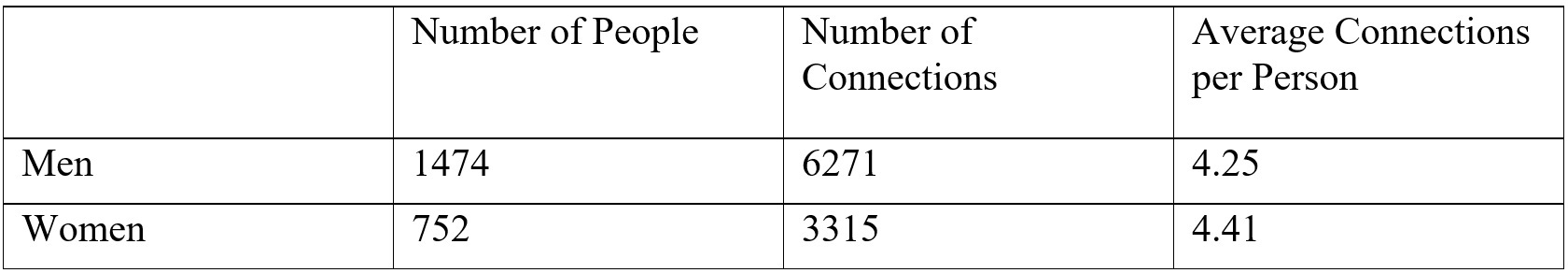

Python and Gephi both provide methods for analyzing the structure and attributes of the network, generating new evidence from which we can draw conclusions regarding women’s multifaceted roles in the cultural sphere of Amsterdam. For instance, in Gephi the graph can be filtered to display only edges (connections) between women (fig. 7). Although women make up a small portion of those represented, they are well dispersed throughout the network. Considering the connections women have with each other and with men (fig. 8), the women represented in the network, on average, have as many connections as the men. Although women are a minority of the individuals represented in the 1630s network, the project’s approach reveals that, as a group, they were deeply enmeshed within the cultural sphere of the 1630s.

In addition to providing new information about women as a group, additional methods can be applied to illuminate individual women who were particularly well connected and active within the network. One such property is centrality, which estimates how central, or important, a node is in the network.25 Gephi offers a suite of centrality measures that can be used to highlight individuals most enmeshed within this graph for further study. One such individual uncovered by the centrality metric is Catharina van der Voort. In the Montias Database, her husband, Pieter Buddens (Boddens) de Oude, is listed as the primary owner of the 1635 death inventory.26 However, the Dutch inscription notes that the inventory contains goods held in common. In the network, Van der Voort is the hub, or most connected node, in her cluster. Alongside her family members, Van der Voort’s cluster contains artisans, artists, and appraisers. A familiar name also appears in this cluster: Susanna Ruts, the owner of Rembrandt portrait of Nicolaes Ruts. In addition to the inventory of goods held in common at the time of Van der Voort’s husband’s death, Montias found another document dated May 16, 1659, in which she transferred artworks to her only daughter, Catharina Boddens.27 Both documents list a wealth of objects, such as several paintings, including a seascape by Jan Porcellius, prints, and a map.28 None of the paintings listed in the transfer document of 1659 match the ones in her husband’s death inventory, suggesting they were purchased by Van der Voort after her husband’s death. This document is one of several legal documents Montias includes in the inventory’s commentary in the database. There are also documents dated between 1636 and 1659 that suggest Van der Voort maintained some level of economic agency as a widow, since she continued to collect works and engage in legal matters.29 A forthcoming article will further examine how Van der Voort navigated society in order to exert her own economic independence and acquire works of art, and it will also detail this project’s materials, method, and results.30 It would not be possible to locate Van der Voort in the web interface of the Montias Database without already knowing of her existence. However, by creating new CSV files that reorganize these data and applying network analysis to those restructured files, dozens of women can be uncovered for continued study. In the hopes of expanding this research, the “Beyond ‘Exceptional’” Python code and CSV files will be freely available on the FARL GitHub page.31

Since women were not the focus of Montias’s research, the original organizational structure of his dataset obscures the important role they played in the cultural sphere as collectors and sellers of fine art and material culture. However, by providing open access to his data in the form of CSV files, FARL offers researchers the unique opportunity to deploy computational methods that deepen our understanding of early modern women’s cultural and economic agency and also counterbalance historical biases against women and other historically marginalized populations. This project just scratches the proverbial surface of what is still to be unearthed in the Montias Database. Several recent and ongoing digital art history projects are using a range of computational methods to explore the rich holdings of the Montias Database, which will greatly expand our understanding of the sale, collection, display, and creation of fine art and material culture in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.32

Digitized art-historical databases are becoming increasingly important in the twenty-first century and will probably continue to gain popularity as institutions embrace the possibilities of digital technologies to expand access to art-historical information. The utility of these databases is determined by an institution’s willingness to be transparent about the creation and stewardship of these digital collections. Scholars must recognize that digital repositories of primary source material are not neutral sources of information. Without transparency regarding the interventions of the cultural institutions that house these repositories, researchers can unknowingly propagate systemic bias. Although there remain barriers to making digitized material truly inclusive and accessible, there is great potential to unearth historically marginalized individuals, groups, and materials, especially when computational methodologies are deployed.

The Dutch Textile Trade Project (dutchtextiletrade.org) and its Visual Textile Glossary, initiated by Carrie Anderson and Marsely Kehoe, stands as a promising example of a database that can advance art-historical research. In the creation of their initial dataset, Anderson and Kehoe carefully considered the issues of transparency, usability, and access raised in this article. Like the Montias Database, the Dutch Textile Trade Project was born out of the founding scholars’ desire to share their materials freely with a broad audience of researchers. Both projects thoughtfully deploy technologies to best meet to these goals. Montias consulted with colleagues at the Getty on how to best structure his spreadsheets, which led to a slight favoring of documents concerning prominent artists, wealthy (male) collectors, and paintings to make these data most useful to art-historical researchers, while Anderson and Kehoe have consulted with textile historians to make sure this site is useful across disciplines. Moreover, Anderson, Kehoe, and their collaborators have recognized the fraught nature of collected evidence—both physical and digital—and are taking great care in collecting and organizing the material in a way that engages with and also critiques the historical biases present in the colonial archival records. Their incorporation of material and visual evidence alongside textual material enriches the dataset, and the addition of the Visual Textile Glossary enhances the accessibility of the database for users. The Dutch Textile Trade Project underscores the importance of new digital databases and digitized material as the field of art history increasingly embraces collaboration and digital technology.