Recent technical investigation of Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger’s Saint Jerome in His Study (1624, London, Courtauld Gallery) in combination with close study of two related works—a print and a drawing—have provided new insights into Van Steenwijck’s working methods and interests, in particular his use of prints. Neither of these subjects has received much scholarly attention heretofore. The article also covers the artistic milieu in Frankfurt where Van Steenwijck began his career at a time when Albrecht Dürer’s legacy was actively continued. And it offers clues about how Van Steenwijck made deliberate use of his background in pursuing a specific type of client in London. The discovery of an autograph letter of 1632, discussed and transcribed in the Appendix by Thomas Fusenig, further adds to our knowledge of Van Steenwijck’s professional and personal contacts.

Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger (1580–before 1640), together with his father and teacher Hendrik van Steenwijck the Elder (ca. 1550–1603), became well known as the first Netherlandish painters to specialize in depicting Renaissance palaces and the interiors of Gothic churches.1 At first glance, Van Steenwijck’s Saint Jerome in His Study (fig. 1), signed and dated 1624 (fig. 2), may not seem characteristic of the art that brought him repute. The small painting is hugely significant, however, as it touches on many aspects of Van Steenwijck’s life and career. It reveals Van Steenwijck as an artist rooted in artistic tradition and connected to a network of contemporaries. This helped him to create works that would appeal to his clients. Finding new clients must have been crucial in light of the peripatetic existence he led: Hendrik van Steenwijck was active in Frankfurt, London, and Holland, and throughout his life he was probably a regular visitor to Antwerp, the city where he was born.2

Saint Jerome in His Study stands out in the oeuvre because of its unusual composition.3 It belongs to the small part of Van Steenwijck’s extensive oeuvre that consists of figural compositions.4 Within this category of works, he took on a few subjects, including the subject of Saint Jerome, which he painted in several variations.5 A typical example is Saint Jerome in His Study from the Portland Collection at Welbeck Estate (fig. 3), which shows the saint as a small figure in a spacious setting, in a landscape format.6 It dates from 1624, the same year as the Courtauld Saint Jerome. This means that both works were probably made in London where the artist had moved by 1617.7

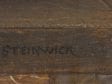

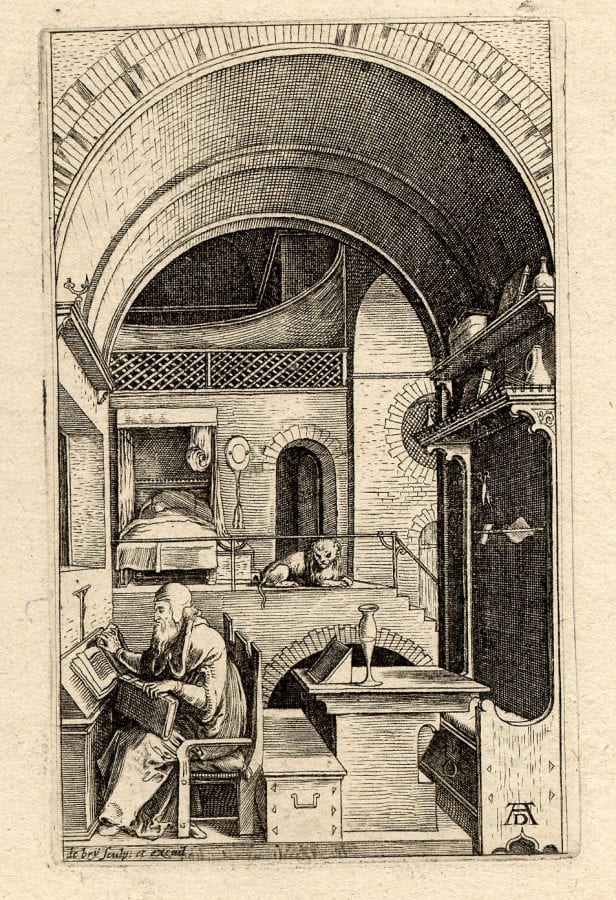

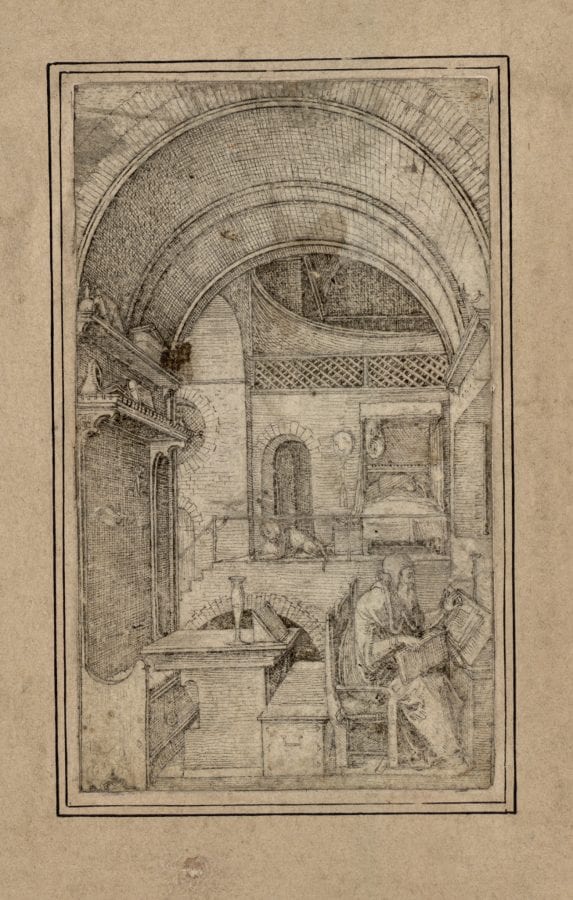

It has long been recognized that its extraordinary composition can be explained by the fact that Saint Jerome in His Study was made after a tiny engraving (fig. 4) by the engraver and publisher Theodor (or Dirk) de Bry the Elder (1528–1598) and/or his two sons, Johann (or Jan) Theodor (1561–1623), and Johann Israel (before 1570–1609).8 The De Brys were colleagues and contemporaries of the Van Steenwijcks, both father and son, in Frankfurt.9 The De Brys in turn based their engraving on a small pen-and-ink drawing, which also survives (fig. 5).10 From the “AD” monogram included in the print, it is evident that they believed that drawing was made by Albrecht Dürer.11

The Genesis and Technique of the Courtauld’s Saint Jerome in His Study12

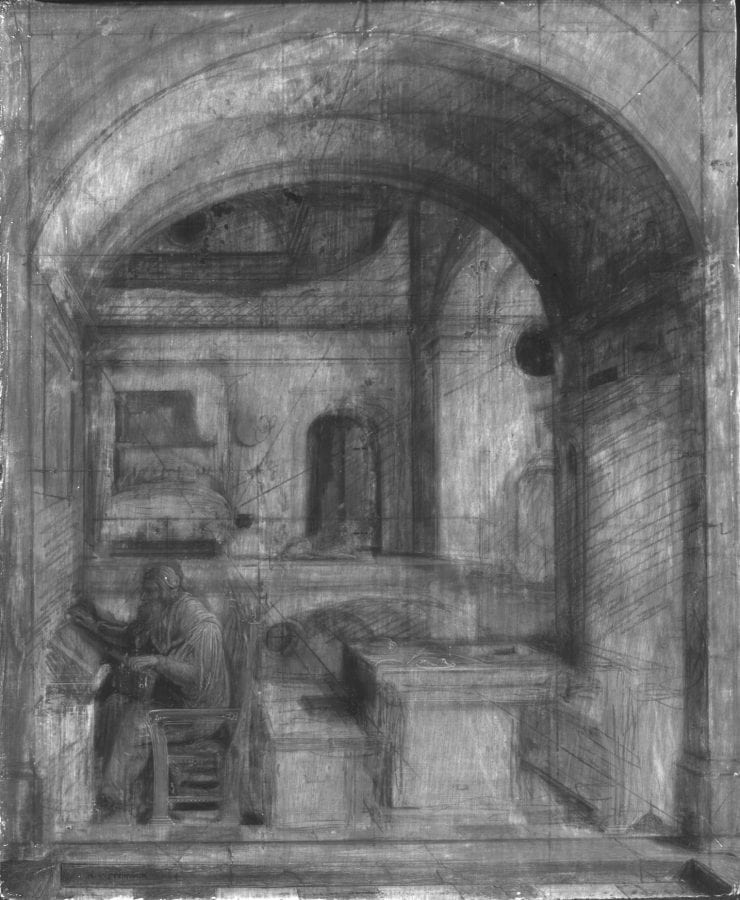

The underdrawing of Saint Jerome in His Study provides new insight into Van Steenwijck’s working methods and interests. The composition of Saint Jerome in His Study was fully and extensively underdrawn (fig. 6) in a combination of straight—apparently ruled—lines and vigorous free-hand hatching in what appears to be a dry medium. The purpose of the underdrawing appears to have been two-fold: first, to position the main elements of the composition on the panel, and second, to prepare and indicate areas of light and shadow.

To achieve the first, Van Steenwijck started mapping out the composition at the outer edges of the panel, as the underdrawn straight lines on all four sides show.13 Van Steenwijck continued “framing” the composition, top and bottom, by adding the arch and the step in the lower foreground. The latter, which achieves a gradual transition to the space of the viewer, is not present in the De Bry engraving.14 The figure of the saint was underdrawn within a separately delineated rectangle.15

In addition, Van Steenwijck made use of an elaborate system of drawn lines to replicate the way in which space is constructed in the print and also to measure and compose the composition.16 Several pinpoints are the remaining evidence of how these straight lines were made. Two of these pinpoints, in the bed, can be seen on the surface as tiny filled holes. One more can be found in the saint’s book (fig. 7). This must have been a time-consuming working method. Thanks to Edward Norgate (d. 1650), we know that Van Steenwijck indeed complained, exactly about this: “The onely Inconvenience incident to Perspective and whereof I have heard Mr Steinwicke complaine with indignation was that soe many were the lines perpendicular parralell and the rest, that another Painter, could compleate a peece, and get his money, before he could draw his Lines.”17 The underdrawing of Saint Jerome in His Study makes Van Steenwijck’s complaint appear perfectly understandable—and truthful.

The underdrawing shows that rather than resizing and transferring the composition by means of a grid, Van Steenwijck used an organized, methodical approach to transfer the small engraving (the direction of the composition indicates that it was the print, not the drawing that was Van Steenwijck’s model) onto a slightly larger wooden support.18

Van Steenwijck’s approach in developing the composition reveals a thorough understanding of architectural space. His attempt to correct and clarify the interior, occasionally conflicted with the earlier model (the sixteenth-century drawing, ultimately) upon which the painting was based.19 An example of an alteration that shows his efforts to rationalize areas of ambiguous space in the interior depicted is the correction of the niche at the left, just above Jerome’s desk. In the underdrawing Van Steenwijck followed the print, where the upper and lower parts of the niche are seen from different vantage points (from a low and high viewpoint respectively). In paint, however, Van Steenwijck strove for a more consistent rendering of the niche. As if to demonstrate its now more fully functional purpose, he placed an hourglass in the niche.

Small differences between the engraving and the painting show Van Steenwijck “updating” the composition, for example by changing the appearance of both saint and lion. He made the saint younger than the model, while the face of the lion turned out, rather comically, more human than animal. The lion’s tail, which is hanging down from the balustrade in the print, was altered at a late stage, in paint, to a position Van Steenwijck must have found more pleasing (fig. 8). The style of the furniture, doorposts, and windows was also modernized. At first sight it seems that iconographically appropriate accessories such as books and other paraphernalia of the daily life of the saint added decorative and narrative detail. Yet these small alterations also served to accentuate surfaces and emphasize a correct and rational construction of space. This demonstrates that Van Steenwijck was not content with merely imitating his model, but that he strove to improve it.

Notwithstanding such thorough preparation, Van Steenwijck painted Saint Jerome in a rather straightforward, simple manner, with thin layers of paint on top of a creamy off-white ground, stretching to the edges of the support. Shadow and highlights were added with a fine brush. Paint was applied swiftly, betraying the artist’s confidence and his great skill as a draftsman. The use of color is subdued, with sparingly applied touches of red, green, and yellowish brown. The limited palette and the painting technique—at once fine and precise but also loose and free—are consistently found in other paintings by Van Steenwijck that are of the same scale, whether on wood or copper panels.20

The De Bry Family, Frankfurt, and the Dürer Renaissance

Saint Jerome in his Study provides a revealing glimpse into the artistic milieu in Frankfurt, starting with Dirk de Bry and his sons.21 Before settling in Frankfurt, Hendrik van Steenwijck the Elder and Dirk de Bry the Elder appear to have already met in Antwerp. In 1577, De Bry was probably admitted to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as “Dierick de coopersnyer ende silversmit,” although the family name of De Bry is not given.22 Immediately preceding Dierick, the admission of Hendrik van Steenwijck the Elder (“Heynrick van Steenwyck, (de oude), schilder”) is listed.23 “Thiery de Bry” was certainly a member of the guild of Antwerp goldsmiths (which was separate from the Guild of Saint Luke) by 1582, when his children Johann Theodor and Johann Israel entered that same guild as his apprentices. Soon thereafter, Dirk de Bry left Antwerp for good, settling in Frankfurt.24 In this other important center of printing, publishing, and selling books (after Antwerp), he founded his publishing business.

When Van Steenwijck the Elder arrived in Frankfurt in 1586, he and Dirk de Bry must have reconnected.25 Many of De Bry’s contacts in Frankfurt can be traced to his Antwerp period; several were members of the Reformed community of which the Van Steenwijck family could also have been part.26 With the deaths in Frankfurt of Dirk de Bry the Elder (1598) and Van Steenwijck the Elder five years later (1603), a definitive transition to the next generation took place, with their sons continuing the family businesses.

Given the longstanding (professional and/or personal) relationship between their families, it is probable that the print of Saint Jerome came into the possession of Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger directly through his contacts with the De Brys. Assuming this was shortly before 1624, the date of the painting, Van Steenwijck must have obtained the engraving from Johann Theodor De Bry.27

As for the drawing, the way in which it came to be owned by the De Brys possibly entailed a similar personal connection between colleagues. Benno Fleischmann attributed the drawing to Ludwig Krug (1488/90–1532), a master working in the Dürer circle in Nuremberg.28 This seems plausible, despite the fact that the extant drawings by Krug almost exclusively show designs for goldsmith work.29 Interestingly, during the last decade of the sixteenth century, two goldsmiths named Krug are documented in Frankfurt.30 They appear to have been immigrants from Strasbourg, the city where Dirk de Bry had started his career. Since goldsmiths and engravers were closely related professions (thanks to their handling of many of the same materials), the goldsmith’s activity was traditionally connected to the making of prints. It seems possible that the Krug and the De Bry families, who had several things in common, either became acquainted in Frankfurt, or already knew each other. Evidence for this remains to be found, however.31

While we do not know exactly how and when the De Brys became owners of the drawing of Saint Jerome “by” Dürer, the fact that they did is not surprising. They came into possession of it during the period around 1600 that has been dubbed the “Dürer Renaissance.” This was a period that saw a great demand among artists and patrons for the master’s works, as well as for personal items. As an example, Van Steenwijck’s uncle Frederik van Valckenborch can be mentioned. Upon receiving a commission in 1607 from Archduke Maximilian III of Austria (1558–1618) to make a now lost copy of Dürer’s Heller Altarpiece (then in the Dominican church in Frankfurt), Frederik obtained copies of the original letters Dürer had written to his patron, the merchant Jakob Heller, directly from Heller’s heirs. In addition, Frederik, who had settled in Nuremberg by 1601, came into possession of Dürer’s death mask, which was made after friends opened Dürer’s grave one day after his burial in 1528.32 While interest in Dürer extended to all of his many activities, Dirk de Bry and his sons may have admired Dürer foremost as an influential printmaker and publisher and also as successful businessman.

By the time it was owned by the De Brys, the “Dürer” drawing must have been deemed a prized possession. This may have played a role in its handling.33 Comparison between the drawing and the print suggests that, proceeding in an incredibly exacting, detailed manner, the De Brys transferred the drawing by eye, reproducing it line by line. The resulting print is a painstakingly correct exact copy.34

The De Bry engraving of Saint Jerome in His Study was executed nearly a century after the drawing.35 It is typical of the tiny prints of the so-called Kleinmeister (“Little Masters”) from Nuremberg, a term that was coined by Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688), who himself received his training from Johann Theodor de Bry.36 The Frankfurt-born Von Sandrart informs us about the level of skill that allowed the De Brys to replicate their model by eye. In his own vita in the Teutsche Akademie (published in Nuremberg, in three volumes between 1675 and 1680) Von Sandrart reports that by a very young age he was able to copy in pen and quill “good engravings and woodcuts” in such a way that his mentor Johann Theodor de Bry and the latter’s son-in-law Matthaeus Merian mistook his copies for original prints.37

Undoubtedly, this kind of training, preserved through master-student apprenticeships, often in a familial context, was already in place during the preceding generations.

Von Sandrart’s remark offers an apt illustration of the level of skill artists like the De Brys (and the Van Steenwijcks) possessed, which allowed them to copy from a model. The insight provided by Von Sandrart could also explain why Johann Theodor (or, perhaps less likely, his brother Johann Israel) executed a print after a drawing by Dürer in the first place—perhaps it was made as part of his training. The importance of prints also helps explain the lack of surviving drawings by Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger: they were not necessary as preparatory material. Van Steenwijck (and his father) could work from prints (or other models), copying these by eye onto the support, then working them up in paint.

Van Steenwijck’s Use of Prints as Sources

Saint Jerome in His Study is not the only example in Van Steenwijck’s oeuvre of a painting that was made after a print.38 Another of his compositions, Saint Jerome in His Study (fig. 9), painted on a copper plate and signed exactly the same way as the Courtauld Saint Jerome (though it is not dated), is also based on an engraving by Dürer (fig. 10).39 It appears that the subject of Saint Jerome prompted Van Steenwijck to turn to an earlier model; Dürer’s famous rendition of the subject must have made him the logical choice to follow. Additionally, as students of perspective, father and son Van Steenwijck may have been particularly attracted to Dürer for his visual and theoretical explorations of the subject.40

A third work by Van Steenwijck that is modeled after a print is Two Figures in a Church (fig. 11).41 The small painting on copper is signed with Van Steenwijck’s monogram and indistinctly dated.42 It was probably made in the years around 1615.43 The source for the composition of Two Figures in a Church was an engraving by Albrecht Altdorfer (ca. 1480–1538), that other prolific German painter and printmaker (fig. 12).44 Altdorfer’s etchings on iron of the synagogue in Regensburg have been dubbed “the earliest Northern prints to have been directed primarily to recording the lineaments of an actual architectural structure.”45 This adds further support to the hypothesis that Van Steenwijck’s attraction to prints by Dürer and Altdorfer specifically originated in his recognition of their achievements in depicting architectural spaces and buildings.

Van Steenwijck must have been acquainted with prints like these from the earliest beginnings of his career in Frankfurt, through his teacher (his father), and through contacts with colleagues in Frankfurt, including printmakers such as the De Brys.46 A contemporary parallel for this can be found in Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610), who began his career in Frankfurt about the same time as Hendrik van Steenwijck the Younger. Elsheimer made several of his earliest paintings after prints by Dürer, Schongauer, Altdorfer, and Baldung.47 Elsheimer must have become acquainted with prints through his teacher, Philip Uffenbach (1566–1636).48 We know that Uffenbach, a printmaker, owned a selection of Dürer’s drawings.49

The works by Van Steenwijck that are based on prints by great past masters were never exact copies. Instead, the artist modernized and improved the models he used. Furthermore, unlike the De Brys and Elsheimer, Van Steenwijck did not turn to these prints as part of his training, or at the early beginning of his career. The Interior of a Cathedral Dedicated to a Profane Form of Worship (Kent, England, Maidstone Museum and Bentlif Art Gallery), a painting from 1624 (the same year as Saint Jerome in His Study), evidences that around this time Van Steenwijck the Younger was preoccupied with prints. Its unusual inscription—in which the father is credited as inventor and the son as author of the composition (Henri van Steinwick Inventor 1591 Henri van Steinwick Fecit 1624)—is the only instance in the oeuvre in which Van Steenwijck distinguished between the idea and the execution of a composition, first and foremost made by printmakers.50

Van Steenwijck’s decision to diversify his subject matter and start producing figural compositions may explain why he, in need of new imagery, turned to prints. In particular while preparing his move to London, Van Steenwijck seems to have specifically tailored the subject matter and style of his paintings to appeal to the interests of an elite, educated audience in England. Van Steenwijck’s turn to prints by Dürer and Altdorfer at this point must have been part of a deliberate strategy.

A Saint Jerome for an English Client?

The earliest known owner of Saint Jerome in His Study is the Honorable Major Robert Bruce (1882–1959), from Glenernie, Dunphail, Morayshire, from whose estate the work was sold at auction on June 20, 1948, where it was acquired by Count Seilern.51 Bruce was a descendent of an ancient Scottish family.52 His distinguished lineage began with Thomas Bruce (1599–1663), 1st Earl of Elgin, and Edward Bruce (d. 1662), 1st Earl of Kincardine.53 While there are many generations separating the earliest known owner of the Courtauld Saint Jerome from Van Steenwijck’s lifetime, its aristocratic provenance may nevertheless be of relevance when further unearthing the work’s first owner.54

Van Steenwijck’s depictions of Saint Jerome in His Study may have been particularly popular with those surrounding the court of King James I and, subsequently, that of King Charles I. These were the same clients who were attracted to Elsheimer’s works.55 The significance and appeal of Saint Jerome, the scholar responsible for translating the Bible into Latin, must have grown in England after the authorization of a new translation of the Bible into English by King James I in 1611. Van Steenwijck’s connections in English courtly circles appear to date from around the same time. A fictive painting by Van Steenwijck with the Liberation of Saint Peter, signed and dated 1613, can be seen in the background of a portrait of the musician, painter, and courtier Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666) (private collection) by an unidentified Netherlandish artist.56 Lanier, who was the brother-in-law of the earlier mentioned Edward Norgate, perfectly fits the type of client who would have been pleased with a painting of the scholar saint in his study.57

Identified owners of Van Steenwijck’s paintings in England show that Van Steenwijck succeeded in reaching an aristocratic, learned audience. For example: the earliest known owner of Saint Jerome in His Study from the Portland Collection at Welbeck Estate (mentioned above), Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford (1689–1741), was a grandson of Robert Harley (1579–1656), master of the mint under Charles I.58 Van Steenwijck probably sought to attract other prestigious patrons, like Thomas Howard (1585–1646), the 2nd Earl of Arundel. His interest in art and, especially, architecture—evident from his collection of books on these subjects—intersected with Van Steenwijck’s.59 Howard also had a keen interest in the work of German masters and owned prints and drawings.60 This shows that interest in Dürer was widespread, not just on the Continent, and not just among artists.61 This elite group of highly educated men, who, among other subjects, were interested in Dürer and in architecture, must have been attracted to Van Steenwijck’s work. After all, he was an artist with experience in, and knowledge of, the same subjects. This particular type of English patron and Van Steenwijck were a good match.

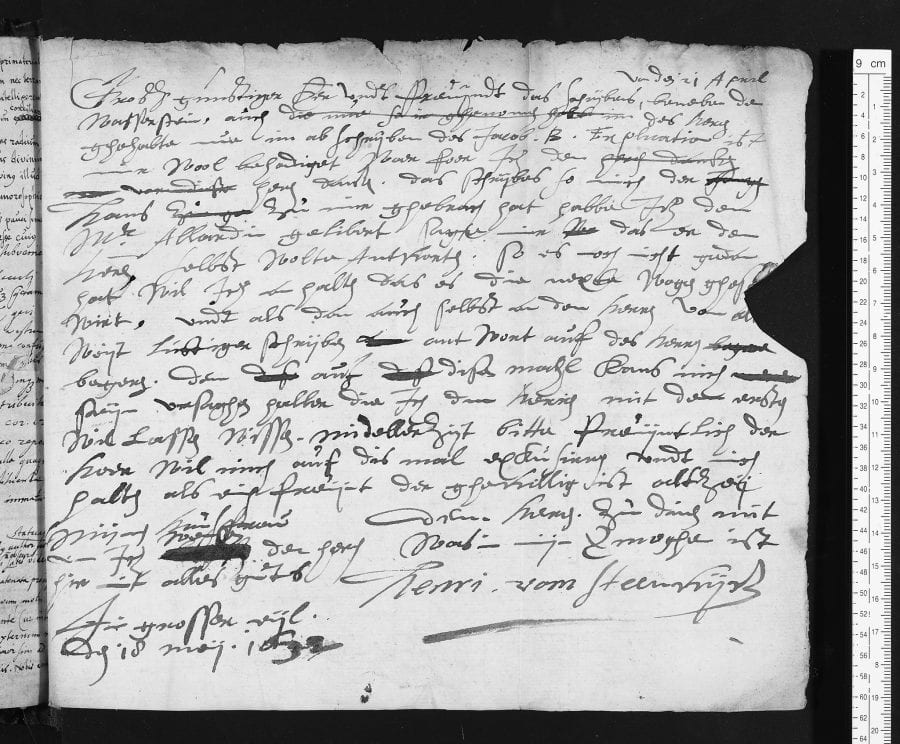

Another of Van Steenwijck’s interests is revealed by Thomas Fusenig’s discovery of an autograph letter from 1632 to the scholar Theodoricus Gravius (see Appendix; fig. 13). The letter suggests that by the early 1630s Van Steenwijck moved in circles of men with an interest in specific scientific and alchemistic knowledge.62 Van Steenwijck’s relationship with Johann Theodor de Bry may have played a role in these contacts. Following his brother Johann Israel’s death in 1609, and after moving the firm from Frankfurt to Oppenheim, Johann Theodor published works of several authors (philosophers, medics, mystics, alchemists) with a scientific/hermetic interest.63 Furthermore, one of the texts mentioned in the letter, referred to as the “Wasserstein,” was published in 1619 by Lukas Jennis, another Frankfurt publisher. Jennis was closely related to the De Brys, since Jennis’s mother had been married to Johann Israel de Bry.64

* * *

The new insights presented here into the genesis of Saint Jerome in His Study have shown that Van Steenwijck was an accomplished draftsman, skilled in the art of composition, proportion, and construction of space. Through his training and contacts in Frankfurt, which included his long-time friends the De Bry family, he was closely acquainted with Dürer’s work. The interest in Dürer, among artists and patrons alike, led Van Steenwijck to turn to prints when he was about to relocate to London. Van Steenwijck’s dealings in Frankfurt, London, and Antwerp, in combination with his peripatetic mode of existence, must have enabled him to stay in touch with an extended network of artists and scholars in different locations.65Although more evidence remains to be found, at the very least Van Steenwijck’s contacts provide an intriguing glimpse into the learned aristocratic circles in which the first owner of Saint Jerome in His Study should be sought.66