Philips van den Bossche (fl. 1604-1615) was the court embroiderer to emperor Rudolf II in Prague. After the death of Rudolf in 1612 Van den Bossche is documented in Augsburg. Apart from a dozen drawings for various purposes, no needleworks have been known to survive. Published here is the first securely attributed needlework to Van den Bossche, a rare example of a work sewn in silk.

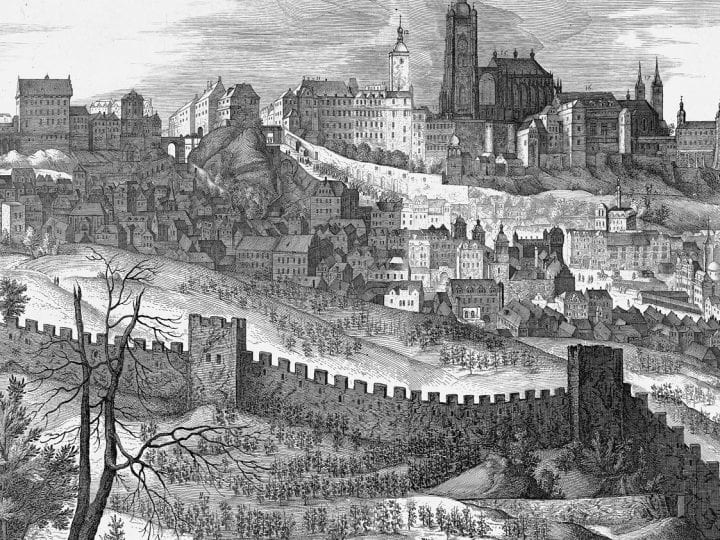

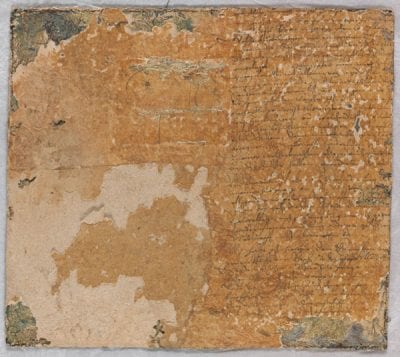

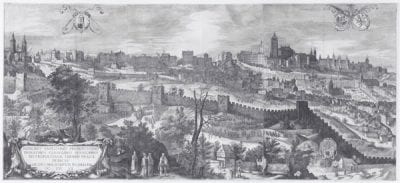

One of the many artists active in the entourage of Rudolf II (1552–1612), king of Hungary and Bohemia and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was Philips van den Bossche (fl. 1604–1615).1 Van den Bossche was active as Camer-Seidensticker (court embroiderer). Nowadays he is best known as the designer of a well-known panoramic View of Prague of 1606 (fig. 1).2 The View of Prague comprises nine separate plates etched by Hans Wechter the Elder (ca. 1550–after 1606), which when combined total more than three meters in length. The print was published by Aegidius Sadeler the Younger (ca. 1570–1629) in 1606. Over a hundred places in the city are keyed by number, all of them described in a separately printed legend. The image as a whole gives a beautiful impression of both the size and splendor of the city of Prague during the reign of Emperor Rudolf II. Of its design only a fragment survives and is kept in the collection of prints and drawings at the University of Göttingen (fig. 2).

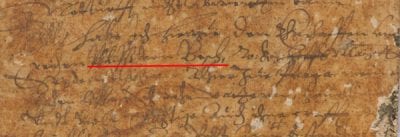

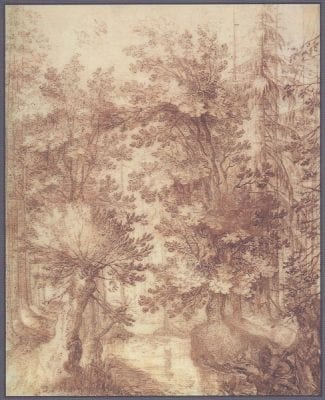

Although he was active as an embroiderer in the service of the emperor, Van den Bossche is primarily known as the draftsman of about a dozen drawings.3 He worked in a style similar to that of such artists as Paulus van Vianen (ca. 1570–1613), Roelandt Savery (1576–1639), and Pieter Stevens (ca. 1567–after 1624), all of whom were active at the Prague court. Van den Bossche’s own way of working is characterized by a strong linearity and short strokes of the pen (fig. 3). The short, often straight lines give these drawings a somewhat flat appearance. One can imagine that this drawing style was prompted by Van den Bossche’s profession as an embroiderer, echoing the short, straight stitches of the silk threads that make up the sewn paintings he was producing.

Both thematically and compositionally, the drawings fit perfectly with the fashion of the time for wooded and panoramic landscapes in the tradition of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In one or two instances we can sense that Van den Bossche had knowledge of drawings by fellow artists Stevens and Savery (fig. 4). The many prints after these artists’ designs by such engravers as the Sadelers and Isaac Maior probably also played an important role in the conception of his drawings, both compositionally and stylistically.

There is no documentary evidence of Philips Van den Bossche’s activity before 1604. It is not known where or when he was born or died. He must, however, have come from the Low Countries. As his name indicates, he was probably a native of ‘s-Hertogenbosch in the northern part of the duchy of Brabant. Like other contemporary Flemish artists, he may have gone south to one of the more important artistic centers, such as Brussels, Antwerp, or Mechelen. After training in the tradition of such landscapists as Hans Bol (1534–1593) and Gillis van Coninxloo III (1544–1607), Philips must have traveled to central Europe instead of the Northern Netherlands (as did Bol and Coninxloo). As is well known, Hapsburg and other sources of patronage in such central European cities as Augsburg, Munich, Salzburg, and Prague attracted many Netherlandish artists around 1600.4 Van den Bossche is first documented in Prague between 1604 and 1612, working as the imperial embroiderer. After that, he is known to have worked in Augsburg in 1615.

The first mention of Van den Bossche is found in the accounts of the imperial court at Prague. As was noted by the scholar Heinrich Modern, the artist entered the service of Rudolf II on July 1, 1604, as imperial Camer-Seidensticker (court embroiderer).5 His salary was set at 30 guilders per month. Apparently the artist had just arrived in Prague, since he received another 150 guilders for moving expenses on September 13, 1604. This rate was generous, as was his monthly allowance — which was more than practically any other artist received at the Rudolphine court.6 The accounts of the following years, however, indicate that Philips never received the total annual salary of 360 guilders. He earned 240 guilders in 1605, 180 guilders in 1606, and 420 guilders in 1607. (The significantly larger amount in the last year may have had something to do with his designs for the View of Prague of 1606.) In 1608 he received 180 guilders, in 1609 120 guilders. The next two years he was paid nothing. The last mention of him occurs in 1612, when he earned 120 guilders. In late January of that year he received another 30 guilders and 42 crowns for “expenses.” This last amount may be connected with the death of Rudolf II on January 20, 1612, and the period of his lying-in-state before his burial on February 5.

From the inventory of the Kunstkammer of Rudolf II–the section “Vonn Seiden mit der Nadel Geneite Gemehl und Tafelein” (paintings and scenes sewn with silk and needle)–it appears that Van den Bossche also embroidered book covers and flower still lifes.7 From the same inventory we learn that Philips had a daughter, Elisabeth, who, along with her husband, H. Cappelman, was active in the same profession. Both are listed with an embroidered flower still life.8 Although a dozen landscape drawings by Philips van den Bossche survive today, as well as the large panoramic view of the city of Prague printed after his design, scholars have not been able to make any secure attributions of embroideries to this artist.

In the past, only one surviving needlework has been attributed to Van den Bossche. The British Museum preserves a small tabernacle with a colored wax relief of a Pietà (fig. 5).9 It is a three-dimensional reproduction of a well-known painting by Willem Key (1516–1568) in Munich.10 The Madonna is dressed with cloth and the hair of Christ has been pasted onto the wax. The background of the relief is particularly interesting, as it consists of an embroidered landscape with figures, a castle, and the hill of Golgotha. The handling of the landscape and the figures (the latter do not appear in the painting by Key) is very similar to that of the extant drawings by Van den Bossche. This led Eliška Fucíková to conclude that the needlework in this tabernacle must be the work of Rudolf’s court embroiderer.11 In the inventory of Rudolf’s Kunstkammer, about fifty of these wax reliefs are mentioned.12 None of these, however, can be identified as the London piece. Although an attribution to Van den Bossche is tempting, the evidence is inconclusive.

A far better candidate for attribution to Van den Bossche is a small needlework (31.7 x 28.2 cm) in a Dutch private collection that depicts a wooded landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (fig. 6). This extremely rare and interesting needlework can be attributed to Phillips van den Bossche on the basis of both style and a contemporary letter pasted onto the back of the work. Built up with various kinds of threads, the scene is embroidered on a linen support. Different dyes have been used to color the silk threads. Silver and gold are the main constituents of the different metallic threads. The XRF and SEM analyses carried out during an investigation of the work confirm what can be suspected through examination with the naked eye, namely that Van den Bossche made extensively use of metallic threads throughout the needlework.13 Gilt silver threads of different thickness and of various manufacture have been used in different areas of the piece: in the foliage of the tree in the middle foreground a thread with a golden tone is much employed to enhance the flickering of the leaves while in the ruined stable on the right, in the part that should indicate the remains of a fachwerk (half-timbered) structure, an entwined thread with a dark, silver-like color can be discerned (fig. 7).14 The rest of the needlework uses colored silk threads to create a vibrant image of Mary, Christ, and Joseph (fig. 8). Philips Van den Bossche used different stitches to produce this precious little work, which is so complex and detailed it might be termed a “needle painting.”15 The sky, the background, and the figures were formed using a split stitch to suggest a smooth progression of the colors. The foliage of the trees and the grass are formed by stem stitches. The stable is formed by a layer of silk strand in which threads are applied on top of the structure and the stitches are alternatively sewn to suggest a brick pattern. The metallic threads are fastened to the needlework by couching stitches. By using this particular stitch it was possible to create a sparkly surface and add depth.16

The scene, with its dense forest and relatively small figures stressing the majesty and force of nature, can be compared to many examples of the landscape art of central Europe around 1600, especially that of (prints after) Roelandt Savery. A drawing in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen that can be attributed to Philips van den Bossche (with some reservation) is equally comparable (fig. 9). There we see a similar structuring of the composition, with the figures of Tobias and the angel pushed into the lower right corner. The way Van den Bossche rendered the trees and their foliage in this needlework, with short straight lines, is something also seen in the drawing from Brussels (fig. 3).

A thin embroidered black line, much of which is lost on the left side of the work, frames the whole. The object is in fairly good condition, although the colors and the glitter of the gold are much reduced by a rather thick layer of discolored varnish.17

The Landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt was at some time in the past glued on a wooden backing. The exact time and the reason for this treatment remains unknown. However, in recent years partial damage to the backing posed a possible threat of damage to the verso of the needlework itself. For this reason it was decided to remove the backing.

When this was done, a paper document, which had been pasted onto the back of the needlework, was revealed underneath (fig. 10).18 Although the handwriting of the document is quite legible, there are several lacunas in the text — a fragment of a letter the beginning and ending of which are missing. The conclusion of the letter was perhaps written on the verso of the paper or even on another sheet, since the text stops abruptly. Around 2 centimeters of blank paper remain at the bottom. On the right, approximately 1 to 1.5 centimeters of the text are missing. Nevertheless, the content of the letter is quite clear: a mandate for Philips van den Bossche to represent the scribe at the chancellery of Braunschweig in Wolfenbüttel (see the transcription in the appendix).19 The author of the letter was in the service of Rudolf II in Prague and had been charged with a capital offence. These charges had been pressed on the first of August 1608. The accused states in this document that he cannot leave Prague due to his numerous activities at the imperial court. Therefore he sends and empowers Philips van den Bossche to represent him in Wolfenbüttel (fig. 11).20 The letter seems to have been written shortly after 1608, since the word abgewichenen is used in connection with this date.

Although the letter and the needlework are not necessarily connected, it hardly seems possible that a written document which must have been in the possession of the imperial embroiderer Philips van den Bossche could coincidentally appear on the back of a needlework likely dating from the first decade of the seventeenth century. Moreover, the style and composition are related to the extant drawings by Van den Bossche, as well as to the works of such artists as Pieter Stevens, Paulus van Vianen, and Roelandt Savery. Thus, we assume that Philips van den Bossche remained in the possession of the letter and used it later to reinforce one of his embroideries.21 Supposedly he did this while he was still in the service of Rudolf II in Prague and before he moved to Augsburg after Rudolf’s death in January 1612. The 1606–11 inventory of the Rudolfine Kunstkammer mentioned above includes a small scene just like the needlework published here: “1 klein täfelin vom Philip vom Bösch ob: tapezier, ist unser fraw und Joseph in einer landtschafft, ligt in einem fütterlin von lindenholtz, von seiden mit der nadel.”22 One wonders if this could be the work published here. In any event, we should consider the needlework under discussion as the first needle painting that can be securely attributed to Philips van den Bossche. This is an extraordinary case. Embroidered paintings like this are extremely rare, and in this instance, we are even able to pinpoint its maker.