Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life.

During the 1950s, when extensive research on the Utrecht Caravaggisti was just beginning to appear, two paintings by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629) entered American collections: Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene and Her Handmaiden at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin, acquired in 1953, and a smaller canvas known as An Old Man Writing by Candlelight (fig. 1), purchased by the Smith College Museum of Art in 1957.1 Inspired acquisitions—all the more for college museums—both offer superb demonstrations of painting itself as well as a level of interpretive richness that can call forth a student’s deepest involvement.

Smaller and less widely known than the work at Oberlin, the Smith College painting has been connected to a variety of earlier pictorial types, although Dennis Weller rightly observed that it belongs among works by this artist that “defy categorization.”2 A further issue, raised in Wayne Franits’s commentary in the ter Brugghen monograph of 2007, is whether the man represented in the painting displays negative archaic qualities such as “the clawlike rendering of the hands and the set of his mouth.” Those would relate the work to sixteenth-century satirical images of elderly misers and moneylenders by Marinus van Reymerswaele and others.3 By examining the image again, this discussion proposes that not only the figure but also the painting as a whole may have another, more complex tale to tell.

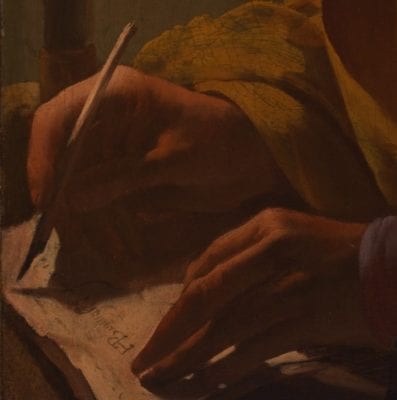

At first glance the subject seems merely another Dutch tronie, or half-length mood study of an anonymous figure, here personifying scholarly engagement. Turned in near profile toward the left, the man, who has a mustache and a bristly unshaven chin, works by candlelight, having just used his quill pen to inscribe ter Brugghen’s signature on the paper before him (fig. 2)—a detail to which we will return later. The folds of his turbanlike nightcap, touched with tones of pink, and his voluminous ocher robe, pushed back to reveal mauve under-sleeves, are powerfully modeled by shifting transitions between the darkness behind him and light from the candle just beyond his right hand. As it rises into the still air, the flame emits a thin plume of smoke, faintly wavering as if responding to the movement of the man’s hand, or perhaps his exhaled breath.

The burning candle and the figure’s designation as an old man in the painting’s current title recall the ubiquitous Dutch vanitas images that express the transience of earthly life. Yet, like a number of seventeenth-century artists—among them Rembrandt and Vermeer—ter Brugghen worked both with and against expectations, complicating any initial assumptions about his subject. Close observation of this rather modest (65.7 x 52.7 cm) canvas reveals a highly selective, closely coordinated grouping of motifs. A strong connection between the figure’s eyes and hand, or between seeing and inscribing, is immediately established by the falling curves of the robe’s wide lapels and by his downward gaze, accentuated by glittering spectacles which catch the light. Suffused with warm tonalities, the image seems to transcend what it represents, as if asking us to consider what its message really is.

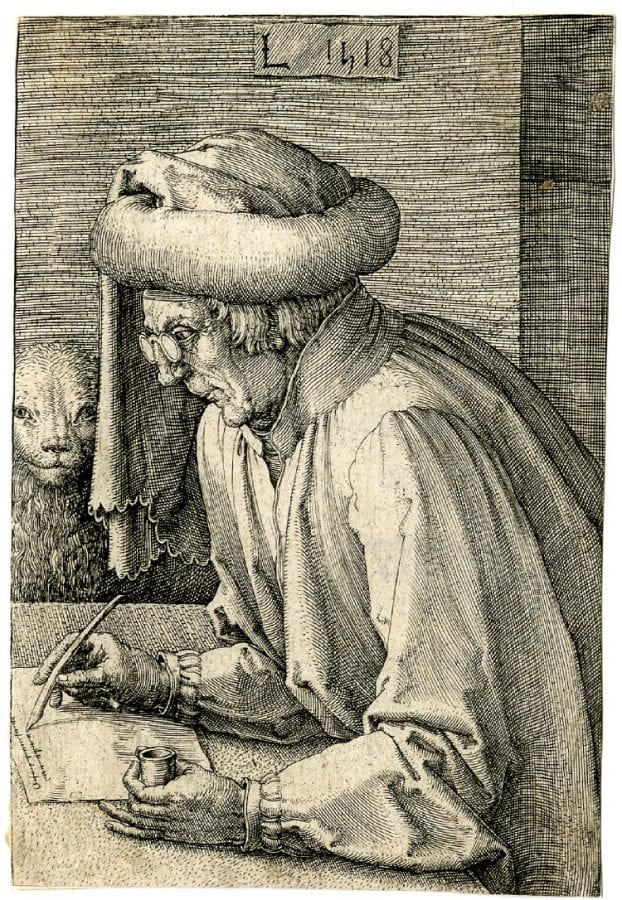

Ter Brugghen’s composition, though not its nighttime illumination, was clearly inspired by Lucas van Leyden’s 1518 engraving of a half-length depiction of Saint Mark in profile (fig. 3).4 Wearing a broader rolled turban with a scalloped tail, he writes his gospel with a quill pen (only word shapes are visible). In both print and painting highly individualized faces gaze at the text in progress through pince-nez, “nose pinchers,” without earpieces, an early form of eyeglasses made to capture light and to magnify and focus vision for both eyes.5 Van Leyden’s glasses even display a rarely depicted but scientifically correct effect: refracted light that forms a small oval of bright illumination high on the saint’s left cheek, an optical phenomenon that in ter Brugghen’s painting becomes a larger and more radiant projection just below the figure’s left eye.6

Similar spectacles appear in sixteenth-century portraits of scholars holding or wearing eyeglasses, in the satirical Netherlandish depictions of avaricious moneylenders mentioned earlier, and in daylight and nocturnal paintings and prints of scholarly saints and philosophers, which remained popular in Utrecht in ter Brugghen’s time.7 The earliest examples of such figures appear in mid-fourteenth-century depictions of scholar-saints in Italy, which became the leading center for the fabrication, sale, and export of spectacles. Germany and the Netherlands soon added substantially to that production after the invention of the printing press in northern Europe around 1450 stimulated the need for assisted vision for reading.8

By the seventeenth century more reliably ground and polished optical glass, although well below today’s standards, was becoming available for telescopes, microscopes, magnifying glasses, and eyeglasses as the lens became a major accelerant for the Age of Observation. Those with sufficient means could visit a professional brillemaaker who offered a well-crafted product.9 Almost anyone, however, could afford the cheap spectacles obtainable from street fairs or traveling peddlers.10 Yet the uneven quality of early modern lenses meant that, even as they came into wider use, they were mistrusted—hence the saying “to sell spectacles” (to practice deception).11 Artists could therefore use this motif to express very different states of mind and motivation: clear-sighted wisdom, shortsighted stupidity, distorted understanding, or even deceptive intention.

Ter Brugghen was well aware of this gamut of interpretative options, for he used men wearing eyeglasses very differently in at least six of his paintings, several of which, briefly reviewed here, offer a context within which to consider the Smith College painting. The Calling of Saint Matthew in the Centraal Museum, Utrecht, dated 1621,12 probably inspired by Caravaggio’s altarpiece of ca. 1600 in Rome, includes an old man at the left, usually identified as Matthew, who wears pince-nez. Ter Brugghen shifted the spectacles to an elderly tax collector at the right, who is clearly blind to the spiritual transformation before him. Ignoring Christ’s arrival to peer at his coins, he reminds viewers how shortsighted is the devotion to worldly richness especially for those of advanced age. In contrast, in the foreground of The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, of ca. 1622 in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, an old man witnesses the moment when the apostle Thomas insists upon testing the authenticity of the resurrected Christ by touching his wound.13 Smiling serenely, he gazes through his black-framed spectacles, his sensitive hands poised near Thomas’s probing finger to express his understanding that true belief requires no verification through sight or touch.14

Yet another bespectacled codger appears in Unequal Lovers (private collection, ca. 1623–27),15 who makes advances to a bare-breasted prostitute. His exaggerated profile recalls the sixteenth-century satiric tradition mentioned earlier along with that of the comedic theme of the “unlikely pair,” in which an unscrupulous girl fleeces a lecherous old fool.16 Here, however, the girl becomes the dupe (and the viewer too) for, as Peter Sutton was first to notice, this leering suitor is really a young man with dark hair under his cap, wearing a geezer mask with a false beard and spectacles.17 As in the Smith College painting, his pince-nez casts refracted light around the eye, but now to imply morally clouded vision.

Unlike these figures, the man writing by candlelight appears in a private moment, not as a character intended to perform, admonish, or amuse. Closely framed and facing the light, he seems vibrantly alive within his own thoughts. His immediate presence, heightened by a touch of light on his slightly parted lips, is expressed by a more deeply characterized face, less typed with manifestations of old age.18 While no longer young, he seems less advanced in years than the figures to whom he has been compared, for a patch of dark hair is visible under his cap, his hands are strong and agile, and his candle is only half consumed. His polished, finely rendered eyeglasses make him appear maturely wise and focused in both sight and thought within this wash of soft illumination. Paralleling the angle of the pen, the tapering fingers of his left hand press gently but firmly against the sheet of paper to hold it in place. As the pen in his right hand pauses, slightly lifted, a subtle play of light and dark captures it as it is momentarily silhouetted above its own shadow on the brilliant page (see fig. 2).

Ter Brugghen’s use of such delicate night-lighting effects, which he incorporated into other depictions of single figures and groups, reflects a recurring Netherlandish interest in candlelight for a variety of subjects. These indications of temporality have been used to intensify both outward dramatic actions and internal states of mind, especially intellectual concentration and spiritual inspiration. Such effects are powerfully presented in a forerunner of the Smith College painting: a work of ca. 1520 in the Rijksmuseum, attributed to Aertgen van Leyden, Saint Jerome in His Study by Candlelight (fig. 4). In it the saint’s musings on the transience of human life seem to take on material form in the candle, burning down beside him, whose softly wavering light reveals his slumped pose and melancholic expression.19 In the seventeenth century new secularized candlelight scenes emerged in Utrecht in the works of ter Brugghen, Gerrit van Honthorst, and Matthias Stomer, but also in Leiden, where Gerrit Dou and his gifted student Gottfried Schalcken expanded the range of single figures pursuing night work to include hermit scholars, doctors, schoolteachers, astronomers, and artists, all subjects of interest in this university center.

The origins and varied implications of working during the dark hours, as interpreted by Dutch artists, have been explored by scholars not only in relation to transience but also to other meanings and associations that may offer additional understanding of the Smith College painting with its presentation of a solitary figure concentrating on his own work. Justus Müller Hofstede has discussed night work as an expression of the virtue of diligence (Diligentia), which allows the fullest use of one’s mortal time. He traced this idea to antiquity: adages by Horace that cite men rising early or working late at night by candlelight to convey the advantages of rejecting a life of dissipation in favor of involvement in intellectual labors.20 In the early seventeenth century Otto van Veen’s Emblemata Horatiana, first published in Antwerp in 1607, would circulate these ideas with printed illustrations throughout the Netherlands.21

Night settings and candlelight have also been used more pointedly to express aspects of artistic training and practice, as implied in antiquity in Pliny’s account of the mythical origin of pictorial representation in shadow silhouettes, projected by candlelight, which may have inspired the earliest drawings of forms in outline.22 Renaissance drawings and prints, as well as Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century, further illustrate how night classes taught young artists to model forms in three dimensions by drawing sculptures or plaster casts dramatically illuminated by candlelight within a dark ambience.23 For students and mature artists alike the depiction of such lighting effects also became a way to demonstrate advanced levels of artistic virtuosity. An artist was expected to achieve even more than simply capturing an evanescent stream of radiance across the forms of living faces and hands. Simultaneously, visual substance must be given to the flame that emits light, the candle that absorbs it, and the surrounding air that holds light in suspension as it gradually diminishes away from its source. Godfried Schalcken, who worked into the late years of the century, used candlelight effects so often that they almost became his signature, especially when the painter gave the figure emerging from shadow his own features.24

Within the masterfully evoked nocturnal atmosphere of Man Writing by Candlelight, one feature of the painting, has been occasionally noted but never fully discussed. This is ter Brugghen’s prominent signature: HTB [in ligature] brugghen fecit (see fig. 2), which the raised pen has just completed, along with the first two digits of an unfinished date (16 . . .), highlighted between the nib and its shadow.25 Authorial inscriptions in paintings or prints, which affirm their creation by a certain person at a particular time, are common and usually inconspicuous, although an artist’s declaration of his own authorship can inspire a bolder announcement. Simon Bening’s little 1558 self-portrait on vellum in the Metropolitan Museum, for example, shows the great illuminator in his studio, spectacles in hand, having proudly named himself in Roman letters on the plaque proclaiming his seventy-fifth birthday.26 Livelier and more pointed inscriptions often link the name with the word or abbreviation for fecit (made it), and the year, written in the artist’s distinctive hand, as seen in Rembrandt’s self-portrait prints.27

The situation ter Brugghen depicts is more unusual, however, because the person in his painting is seen to be in the actual process of inscribing the signature and date himself. It is not surprising that such rare “signing” inscriptions are more likely to appear in depictions of artists and writers in the graphic media since both professions involve making marks or lines whose manipulation can alternatively produce images or words. An upside-down example appears in a drawing by Jacques de Gheyn II of a young man writing at a table (fig. 5), probably his son Jacques III, who was also an artist, as he has just written IDGheyn III in.28 Similarly, Samuel van Hoogstraten’s self-portrait (fig. 6), the frontispiece of his 1678 treatise on art, features a block of text below the figure, proclaiming the author’s equal adeptness with “pen en penseel” (pen and brush).29 Above it is the man himself, whose artistic power is confirmed by the imperial gold medallion and chain he was awarded by Frederick III and by the Atlas figure lifting the world at the left. Confronting us directly with his level gaze, Hoogstraten holds the pen, which has just inscribed his initials and age below his portrayed self, identifying him as both the person who wrote the text and the artist who delineated the image.

Nicolson described the figure in the Smith College painting as “forging ter Brugghen’s signature,” but it seems more likely that he is in the process of finishing his own work, signing and dating a document on his desk in a way that ingeniously refers to the painting too.30 As Müller Hofstede observed, showing the actual process of inscribing a signature can demonstrate an artist’s professional zeal in having finished a manifestly completed work.31 Are we therefore to conclude that this man is ter Brugghen himself, displaying his diligence and virtuosity to the viewer? Since the work has been dated toward the end of his life (he died in 1629 at the age of forty-one), at a time when people aged faster and died earlier than they do today, it could conceivably represent him in middle age. Yet the figure does not present himself to be looked at, as portrait subjects like Hoogstraten normally do. Leaving aside the absence of a reliable comparison to verify likeness,32 this painting seems less a literal depiction of its maker’s appearance than an expression of his thinking about himself and his profession, recalling the Italian adage “ogni pittore depinge sè” (every painter paints himself).33

As seventeenth-century Dutch artists strove to raise the status of painting from its classification as a manual craft, the trope of the learned painter, or Pictor Doctus, emerged in self-portraits of artists writing or contemplating attributes of knowledge.34 A reversal of that notion might be applied to this artful scholar (Doctor Pictus) in the Smith College painting, who wields a pen and signs his work with the painter’s name in the presence of powerful allusions to the sense of sight: the candle flame which brings tangible forms from darkness into visibility and the lens of his spectacles which pulls incorporeal light into that radiant refraction beside his eye.35 Prints of this period that show art students working by candlelight, alone or in night classes, are reminders of the intensive training and practice needed to master evanescent lighting effects—a point perhaps implied in the Smith College painting by the juxtaposition of the man’s working hand with the candle.36

Interestingly, additional parallels between artists and writers were emerging in ter Brugghen’s time in the taste for beautiful virtuosic calligraphy and pennetrekken (pen pictures), which were displayed in both printed publications and live demonstrations.37 As Ann Adams has discussed, graceful italic script of the kind used for ter Brugghen’s inscription reflects a new development in artists’ signatures intended to express culture and learning while signaling a shift from authorial anonymity or the plain workshop stamps of earlier times—the latter perhaps invoked in the block letters which begin this inscription.38 That it trails off into an uncompleted date intensifies the effect of a fleeting moment within the creative process, as well as the power of painting to enduringly capture both its own process and the culmination of it.

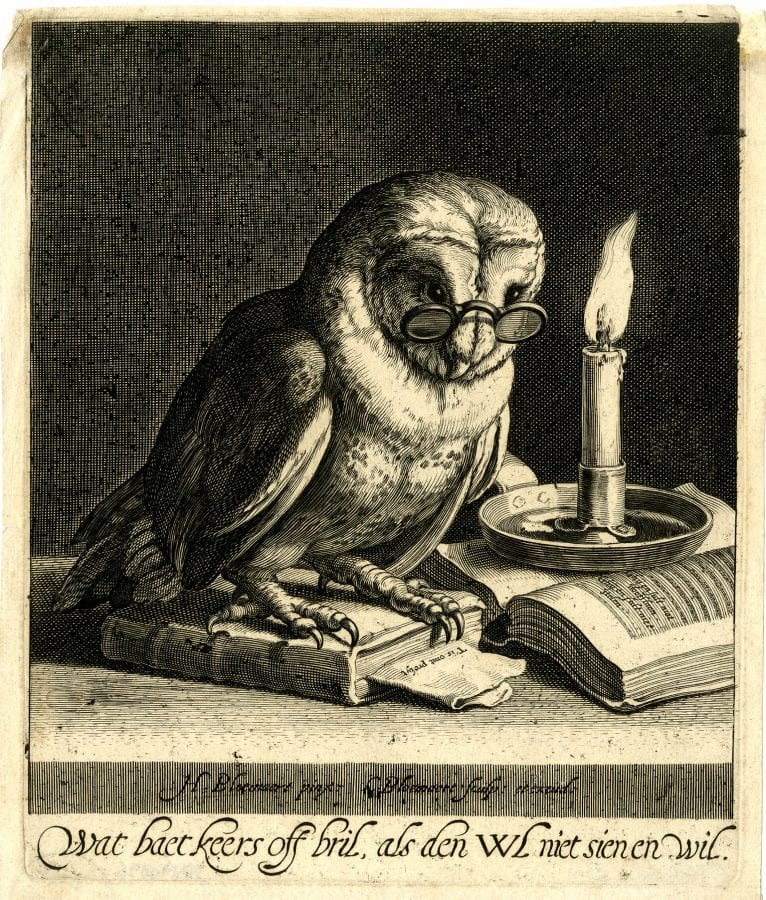

In its expressive fusion of light and sight Man Writing by Candlelight conveys the ambiance of a period in which the quest to receive and process visual experience, often enhanced by optical aids, led to a deepening of thought in art, in science, and even in people’s reflections about their everyday life.39 A constellation of motifs, strikingly similar to those in ter Brugghen’s painting, appears in a witty emblematic print by Cornelis Bloemaert (fig. 7). Here an owl, absurdly supplied with pince-nez and candle, perches on a closed book above the adage: “Wat baet keers off bril, als den WL niet sien en wil?” (What use are candles and spectacles if the owl refuses to see?).40 The message—that the ability to “see” (to be wise) can only be self-generated and that no visual aid can make it happen without internal motivation—becomes in ter Brugghen’s painting a vividly experiential image which arouses and celebrates the sense of sight so fully that the artist’s fineness of perception and his joy in expressing it immediately become our own.