Hendrick ter Brugghen painted two versions of the Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John: one is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the other in a private collection in Turin. The latter canvas, although cut down, is much larger than its New York counterpart. An examination of the relative stylistic qualities and provenances of both canvases leads the author to raise the question of whether the Turin version might possibly be the primary one and not the picture in New York, thus reversing long-standing assumptions concerning their relationship to one another. The essay concludes by examining the recent attribution of several paintings to ter Brugghen’s Italian period.

There are two surviving paintings of the Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John by the Utrecht Caravaggist Hendrick ter Brugghen. The first, the best known of the two, hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) in New York (fig. 1), and the second is in a private collection in Turin (fig. 2). It is highly fitting to examine them in this issue of the JHNA dedicated to the memory of Walter Liedtke since Walter and I discussed these two pictures extensively while each of us was engaged with large projects: the MMA’s Dutch paintings catalogue and the late Leonard J. Slatkes’s monograph on ter Brugghen.1

In his masterful entry on the MMA Crucifixion for the Dutch paintings catalogue, Liedtke argued for this canvas’s primacy among the paintings of this subject associated with ter Brugghen.2 He addressed its oft-commented-upon archaic qualities but insightfully remarked that ter Brugghen’s crucified Christ was “almost graceful” compared to his counterparts in German and Netherlandish art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Liedkte perceptively argued in favor of construing the Christ figure as “a Baroque emulation of earlier art, not the untempered imitation of an older model.”3 The figures of the adoring Virgin Mary and Saint John were likewise cited for their sophistication and contemporaneousness.

As for the Crucifixion in Turin, Liedke admitted that he had never actually seen it. But this fact did not prevent him from taking the unusual step of adjudging it a copy after ter Brugghen solely on the basis of a photograph. To the contrary, Leonard J. Slatkes believed that the Turin Crucifixion was an autograph replica (with some variations) of the MMA version; like Liedtke, he, too, considered the latter the prime one.4 Slatkes called attention to Christ’s altered pose in the Turin version, most evident in the position of his legs vis-à-vis Saint John’s garments: a substantial section of his shin bone touches the saint’s robe, while in the MMA version only Christ’s knee makes contact with it. Both pictures contain footrests in the form of wooden planks for Christ’s feet. The wooden plank in the Turin version is quite large and situated at a lower point on the cross, running the entire width of the vertical beam. It supports both of Christ’s feet, which are depicted almost side-by-side, as opposed to the MMA Crucifixion wherein one foot is completely under the other. In effect, this shifts the angle of Christ’s legs and to a lesser extent that of his upper body and head, thereby causing the visual discrepancy between the two canvases.5 In part, this explains Slatkes’s observation that the crucified savior’s overall compositional position relative to that of the Virgin Mary and Saint John is higher in the Turin version than in the MMA version.6 Curiously, he speculated that this figure of Christ had been overpainted “most likely after it [the canvas] had arrived in Italy” in order “to moderate some of the more Northern European qualities.”7 This very same claim was made for the sky because it features dramatically illuminated and striated clouds versus the cloudless, starry sky in the MMA version. Nevertheless, Slatkes was unable to muster any technical evidence to support his hypothesis concerning the picture’s supposedly altered state.

What prompted Slatkes’s speculations was the slightly broader brushwork of the figure of Christ, a technique he associated with a northern Italian mode of execution. The present writer examined the Turin Crucifixion in detail in July 2015. Beyond the aforementioned deviations between it and the MMA version in Christ’s altered pose and position with respect to the two figures below, the Virgin Mary wears a different colored garment beneath the large swatch of drapery enveloping her form and the same is true of her headband. Saint John’s pose diverges subtly from his counterpart in the MMA version in that he does not crane his neck as acutely to view the crucified Christ. His shoulder is also lower. Moreover, the streams of blood flowing from Christ’s nail-punctured hands are not only heavier, as Slatkes noted, but considerably longer than what is seen in the MMA Crucifixion.8 And Christ’s body in the MMA Crucifixion exhibits a distinctly greenish hue lacking in the Turin version.

With respect to the picture’s execution, an ever so slightly broader or looser touch of the brush is indeed evident in the figure of Christ and the light-streaked sky. But the picture offers absolutely no evidence of having been overpainted. Rather, these passages simply display a more spirited technique on ter Brugghen’s part. And most significantly, other passages very directly recalled the MMA version, for example, the alabaster highlights in the hands of Saint John and the Virgin Mary,9 while still others display a slightly harder facture, best evidenced in the contour of Saint John’s face compared to that of his MMA counterpart. In the end, the degree of broadness or smoothness inherent to this brushwork varied in both canvases.

Both Liedtke and Slatkes noted the size discrepancies between the two Crucifixions, which were once even more dramatic, for the Turin version has been cut down on all four sides, most drastically at the bottom.10 Even a casual glance at the picture confirms this: Saint John’s robe abruptly ends at the right edge of the canvas, while the Virgin Mary’s robe touches the left, and both figures are terminated at their thighs. Christ’s cross likewise fits uncomfortably within the space: its top with the banner bearing the inscription INRI—cartellino-like in the MMA version—is missing.11 At the opposite end, the foot of the cross with the skull and bones, the latter, a poignant vanitas motif in the MMA Crucifixion, was long ago cut away. This loss seems critical because ter Brugghen signed and dated the MMA canvas in precisely this location. Despite its rather severe truncation, the Turin Crucifixion still measures 188 x 173 cm. If it were uncut and hence depicted full-length figures and a complete cross, it would measure approximately 300 x 185 cm, making it two times the length of the MMA version and by far the largest painting in the artist’s entire oeuvre. Possessing such dimensions, it could only have been intended as an altarpiece.12

Since 1964, the Turin Crucifixion has hung in several private collections in that northern Italian city in the province of Piedmont. But prior to that date, it was thought to have hung in a private chapel in the small town of Casale Monferrato due east of Turin.13 Noting the picture’s earlier location and its relation to Italian conceptions of style, Robert Schillemans considered the Turin Crucifixion unique and assigned it to the artist’s perplexing Italian period.14 Ter Brugghen probably left Utrecht for Italy during the summer of 1607. Although the exact date of his arrival there is uncertain, scholars are on much firmer ground concerning his departure from Italy: an archival document places the painter in Milan during the summer of 1614 noting that he and a colleague came to the aid of a young painter there while en route to the Netherlands.15 Interestingly, Casale Monferrato lies just over a hundred kilometers southwest of Milan. However, the crucial question of the year in which the Crucifixion was possibly installed in a private chapel in that small town cannot be answered owing to the absence of documentation.

Problems of provenance aside, what really militates against the theory of an Italian-period genesis for the Turin Crucifixion are its figural types. In comparison to those found in the earliest indisputably authentic ter Brugghen religious paintings made after his return to Utrecht—and here I am thinking of the Le Havre Calling of Saint Matthew, the Lublin Pilate Washing His Hands, and the Amsterdam Adoration of the Magi—their conception is just too far advanced.16 They can be more convincingly linked in body type, facial features, garments, and so forth to such canvases with sacred subjects as the Rotterdam Penitent Saint Jerome, the London Jacob Reproaching Laban, and the Berlin Esau Selling His Birthright.17 These works all date to around 1624–27, and two of them similarly manifest ter Brugghen’s renewed attention to Italian conceptions of style, some ten to twelve years after he had departed Italy.18

So what conclusions can be drawn from the preceding discussion? First and foremost, the canvas in Turin is certainly not a later copy of the one in the MMA by an as yet unidentified artist, as Liedtke surmised. Slatkes was correct in considering the Turin Crucifixion an autograph work sent to Italy years after ter Brugghen’s return to Utrecht. Compared to the MMA Crucifixion, certain passages of the Turin canvas, most notably the body of Christ, exhibit a slightly looser execution, but other passages, among them the contours of Saint John’s face, are somewhat more tightly treated than in the MMA picture. Still, there is no evidence of the Turin Crucifixion having been altered in any way upon its arrival in Italy in order to moderate its supposedly Northern European qualities. Rather, ter Brugghen must have conceived of it, undoubtedly a commission, with Italian tastes in mind. Furthermore, the canvas’s original location in Italy is unknown. As noted above, although it was thought to have hung in a chapel in Casale Monferrato prior to 1964, no documentation exists to verify precisely when it might have been installed there. The current state of the Turin version is the result of its having been trimmed on all four sides. In this respect the loss of the bottom of the canvas is particularly frustrating because this is where the MMA version was signed and dated by the artist; presumably, a signature and date were once visible on the Turin version as well.

The last digit of the date of the MMA Crucifixion is no longer visible, but it is generally thought to have been painted circa 1624–25, a period to which the Turin version can also be assigned.19 The MMA painting is also sharply reduced in size in relation to its Turin counterpart, all the more so if the latter had retained its initial impressive dimensions. Liedtke thought that the MMA Crucifixion was destined for a clandestine Catholic church in Utrecht. However, his hypothesis is problematic because it is difficult to reconcile with the picture’s earliest recorded provenance in the stock of a Delft art dealer in 1657.20 It is not very likely that a hidden church would have sold such a valuable painting within twenty-two years of its commission.21 To the contrary, the MMA canvas must have initially been in private hands. Given its reduced size and probable early history, one wonders whether the MMA Crucifixion is an autograph replica (with some minor deviations) of the Turin version.22 Unfortunately, just such a chronology for the two paintings is impossible to confirm, but it is well worth considering.

Schillemans’s theory of an Italian-period genesis for ter Brugghen’s Turin Crucifixion is not the only instance in which a picture has been assigned to this perplexing phase in the artist’s career. His approximately six-year stay in Italy has remained shrouded in mystery for the simple fact that beyond the Turin Crucifixion, not one of the precious few paintings that specialists have attempted to tie to those years has been unequivocally accepted as autograph. The problematic nature of these attributions holds true, in my opinion, for three additional paintings that have more recently been associated with ter Brugghen’s earliest development. Incidentally, it is telling that none of these three works resemble one another.

A recent claim of this sort involves a very large painting portraying the Denial of Saint Peter. Auctioned at Tajan in Paris in 2007 as an authentic painting by ter Brugghen, this canvas is presently in the Spier Collection in London (fig. 3).23 In the spring of 2015, this picture was on view in an exhibition at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence principally devoted to Gerrit van Honthorst. In his catalogue entry, Gianni Papi dates the Denial of Saint Peter to circa 1611–12, praising it as a unique and decisive picture from ter Brugghen’s Italian phase.24 Moreover, he notes its close visual relationship to the artist’s painting of the same subject, dated circa 1626–27, in the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 4). Papi also ties its light effects to the earliest phase of van Honthorst’s activities in Italy even as he opines that this master’s works lack ter Brugghen’s crude application of color and facially deformed figures.

I have examined this “new” Denial of Saint Peter twice: in March 2014 when it was at a restorer’s studio in London and, for a second time, at the Uffizi exhibition. Neither occasion convinced me of its authenticity. Its relationship to the Chicago Denial of Saint Peter cannot be doubted, but its brushwork, particularly that of the maid’s dress and sleeves, is far too schematic for an authentic painting by ter Brugghen. The relatively crude paint application along with the awkward anatomical details of the figures bespeak a picture painted by another hand sometime after the one in Chicago, even if one recent reviewer of the Florence exhibition inexplicably hailed it as a masterpiece of the artist’s Italian sojourn.25

Gert Jan van der Sman has raised the intriguing possibility that the Spier Collection canvas might be a later copy after a now-lost painting, “L’historia di S. Pietro e l’ancilla by “Enrico d’Anversa,” recorded in the 1638 inventory of the famed Giustiniani Collection.26 Giustiniani had made reference to this very same Enrico in a letter he composed before 1620; this mysterious artist has since been identified as ter Brugghen himself.27 The dimensions of the Spier Collection Denial of Saint Peter approximate those of the lost Giustinani picture, thus lending support to van der Sman’s hypothesis.28 The striking light effects of this painting and such captivating passages as the almost abstracted smoothness of the legs of the slumbering soldier in the right foreground are reminiscent of paintings by Georges de la Tour from the latter 1630s and 1640s. Perhaps this work was made by a Franco-Flemish or Italian artist active in Rome in the 1630s or beyond. The Chicago Denial of Saint Peter would thus constitute a reworking of the lost original in a different format.

Another painting allegedly belonging ter Brugghen’s Italian period is a Fortune Teller (fig. 5), first published by Mina Gregori in 2011 and featured in the exhibition Roma al tempo di Caravaggio 1600–1630, held in Rome in 2011–12.29 Despite Gregori’s claims to the contrary, it bears no resemblance to any authentic painting by ter Brugghen from any period in his career. Her attempt to link it to a painting depicting the Beheading of the Baptistin Edinburgh is suspect in that this latter picture is clearly a crude old copy of a now-lost work.30 The basis for Gregori’s attribution of the Fortune Teller to ter Brugghen lies in the fascinating inscription on the back of the canvas: aegiptia. credulo. divx. / enrico. ter. bruggo. flamo. pinxit. ad. mdcxii.31

A similar inscription, with almost identical lettering, can be found on the back of a canvas now given to Simon Vouet (Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica) of the exact same subject. Rossella Vodret made that discovery on the occasion of that painting’s restoration in the mid-1990s and later convincingly traced its provenance to Cassiano dal Pozzo’s collection.32 The presence of both Fortune Teller canvases in the dal Pozzo collection prompted Gregori to propose that both Vouet and ter Brugghen had been asked to paint this Caravaggesque theme so that the collector could assess their skills as neophyte artists.33 But it seems to have never occurred to Gregori, or, for that matter, to Vodret, that these inscriptions, added as they were as late as the eighteenth century, might be incorrect.34 After all, stylistic traits should form the basis for attributions, not inscriptions.35 In fact, Richard Spear questioned the authenticity of this so-called ter Brugghen Fortune Teller in his review of the exhibition, as did Gianni Papi.36 This picture’s high-key palette and pronounced painterly facture makes one wonder whether it could be more suitably placed in the orbit of an artist like Johann Liss, who worked in Venice after 1622.37

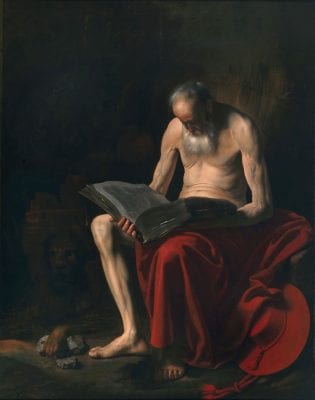

One final picture to be considered is a Saint Jerome first auctioned as an Italian-period ter Brugghen in 2006 (fig. 6) on the basis of an attribution by Marco Gallo.38 In his view, several anatomical deficiencies in the figure of Saint Jerome indicate an early date for the painting, perhaps as early as 1610 (but no later than 1615), but it is nonetheless said to reveal ter Brugghen’s exposure to Roman art. Much like Gregori, Gallo summons a questionable ter Brugghen with which to compare and corroborate his discovery, in this instance the Toledo Supper at Emmaus, wherein the physiognomies and drapery renderings are said to recall those of Saint Jerome. However, specialists do not universally accept the Supper at Emmaus as a bona fide ter Brugghen despite its having retained the remnants of a date of 1616.39 I agree with Gallo’s supposition concerning the painting’s Northern European authorship but see no compelling reason to associate it with ter Brugghen given the marked stylistic differences between it and authentic works by the master. It therefore comes as no surprise to learn that Gallo’s initial attribution (in 2006) has already been challenged: when Saint Jerome appeared again on the auction block in 2013 it was simply ascribed to a “Caravaggesque painter.”40 I believe a similar fate awaits the other “ter Brugghen” paintings discussed here should they ever again come up for sale.