This article explores the ways in which the Dutch Textile Trade Project contributes to broader discoverability of terms by employing and contributing to a taxonomy and expanding controlled vocabularies.

Introduction

On a daily basis, we come in contact with vocabularies (ways of describing and contextualizing our world) in a technical sense; and we can recognize the value of controlled vocabularies and ontologies (structural models using hierarchical, controlled vocabularies) even if we are unfamiliar with the technical implications of the terms. Web search engines use an ontological model all the time because it enhances the relevance of a user’s search results. For example, an ontological model returns a search for the term “Venus” with categorized results for Venus Williams (under News), Venus de Milo (Arts and Culture), or razors (shopping).1 For example, searching for “textiles” on Google will yield 1.08 billion results in less than a second, but these results are extremely broad and include textile sellers, Wikipedia definitions, and instructional videos, among other topics. Adding the term “Dutch” to “textiles” refines the search to 4.5 million. But what are “Dutch textiles” here? Industrial textiles made in the Netherlands? Historic textiles in Dutch museum collections? Adding the term “trade” gets a user closer to the topic of this special issue. A controlled vocabulary—a set way of spelling the term “textiles,” for instance—ensures that the results are consistent.2 So, for example, when a user types “textiles” (plural), the search engine will also return all results referring to the term “textile” (singular). Adding the context of “Dutch” and “trade” helps an end user understand what a textile is in relation to other variables.

A taxonomy, or system of classification, defining “textiles” allows for greater discoverability because it places a term in a hierarchy.3 Hierarchical taxonomies can also help us understand the relationships between different types of textiles, while ensuring consistency within a given type. For example “sailcloth” is part of the following (simplified) hierarchical structure:

Materials

>materials by physical form

>fiber by product

>textile

>canvas

>sailcloth4

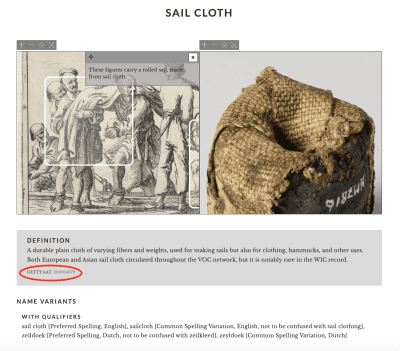

The defined terms create a set of statements and words that make up a controlled vocabulary.5 While these terms can have name variants (like “sail cloth”), the primary term is consistent, and most importantly, it possesses a unique identifier (most often numeric or alphanumeric), meaning that if the term is updated, the words will still resolve to the same term. Even if the term “sailcloth” evolves to “cloth(sail),” its unique identifier (300014079) will ensure that both versions lead those seeking to the same term. Further, any name variants such as and including misspellings, or the same word in other languages, can be captured and documented in that same record for end users to correlate in the future

Controlled vocabulary terms connect with related terms to build out semantic ontology—that is, a collection of hierarchical, controlled vocabularies (taxonomies) which give context to something. An ontology is built on a knowledge graph, based on human understanding and contextualizing of multiple attributes. As such, an ontology can employ multiple controlled vocabularies in a defined domain. The Dutch Textile Trade Project’s visual glossary seeks to illuminate the context for these many textiles as they relate to geographic circulation, price, quality, and visual characteristics.

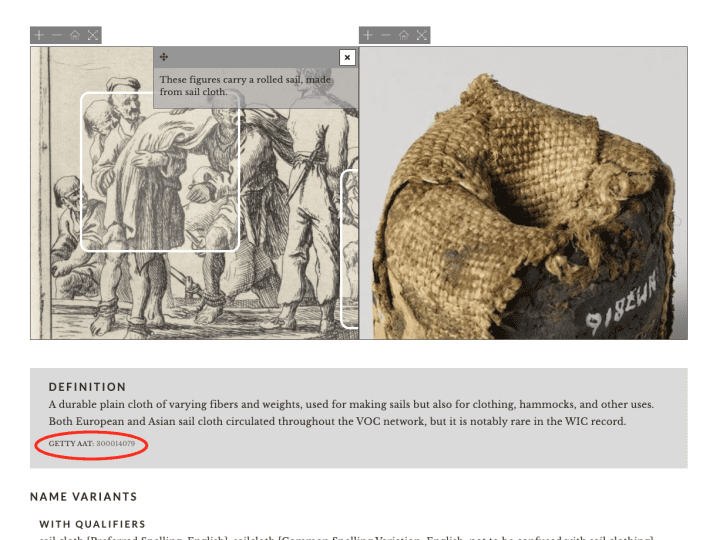

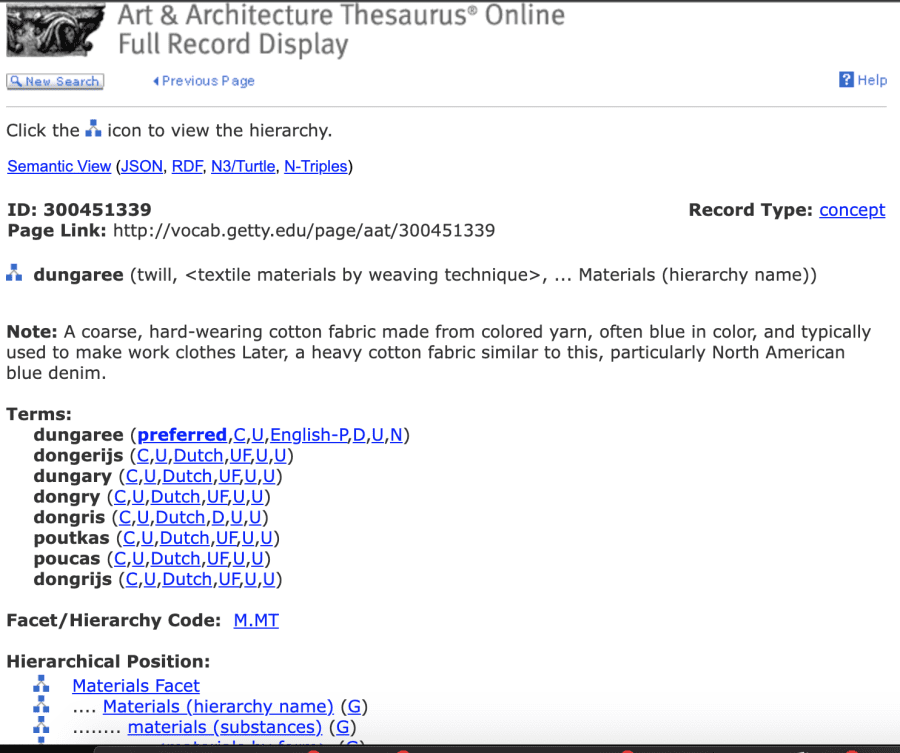

Many of the textile terms and materials studied and documented by Carrie Anderson and Marsely Kehoe lack any sort of cohesive or consistent definition, which complicates their discoverability (some of these challenges are explored in their essay in this issue).6 In the context of controlled vocabularies, these textile terms have not had a firm, hierarchical scope and definition. For instance, how can an obsolete term like “dongris” be accurately placed in a taxonomy and described when its use, fiber type, and physical qualities are unclear? In an effort to bring clarity to these historical terminologies, Anderson and Kehoe have constructed a visual textile glossary—which will expand over time—in order to advance the study of these critical commodities.7 Considering the many ways data can be mined, this glossary is composed of words (terms), images, and material samples, which bring a greater depth of knowledge to the materials used in trade by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Dutch West India Company (WIC). Primary textile names serve as the title for each visual glossary entry, while name variants appear below, as in fig. 1.

The name variants themselves take their cues from archival and secondary sources and include a host of linguistic references, such as Dutch, English, Danish, and Portuguese, as well as alternative misspellings. These variations are invaluable when mining the archives because they facilitate comprehensive consistency.

Benefits of Using a Controlled Vocabulary

Published vocabularies like the Getty Vocabularies, the Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (RKD)’s Iconclass, and the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) provide permalinks to set terms, available via API (Application Programming Interface) or manually placed, so that museums, universities, and independent projects can deliver consistent naming and definitions for cultural heritage objects, artists, and the like, without the additional overhead of having to maintain the definitions. So, for example, a U.S. museum’s database might note a seventeenth-century Dutch painting as being on “canvas,” but a Dutch museum database might describe the same material support as “doek” (cloth). Ensuring that both searches return the same result is the benefit of using a well-maintained controlled vocabulary (see fig. 2).

There is also a symbiotic relationship between what Anderson and Kehoe establish with the Dutch Textile Trade Project and the common art-centric vocabulary resource of the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT).8 Noticing a lack of available terms relevant terms to textiles in the AAT, Anderson and Kehoe devised their dataset around the terms themselves and are working on building structured definitions. Ultimately, they will deliver their submissions to the AAT team to add to the growing body of research on these terms.

Additionally, as the Getty Vocabularies ingest new terms, each term is assigned a uniform record identifier (URI) as a permalink, ensuring that there is a persistent marker to track a textile term and a uniform way of referencing not only the primary term but also any name variant recorded to date. The Dutch Textile Trade Project’s site has the back-end infrastructure to utilize these URIs to connect these textile terms back to the AAT, which will also facilitate additional connections to other textile sources, projects, and archives.

The application of terms to these textiles ensures that textile historians will be able to discover this content with authoritative definitions but also that economists, art historians, and historians alike will be able to uncover and learn about a textile, purely based on the descriptive tag placed on the term.

Expanding the Vocabulary

The absence of Dutch trade textiles from the AAT is not necessarily surprising, as textile research has been marginalized in broader art history until recently.9 The AAT’s baseline came from the art historical foundations in archives, largely focused on references to European Old Master paintings (Renaissance though modern), for which documentation has been fairly standardized since the inception of art history in the nineteenth century. The ways materials—particularly more industrial materials—were documented was less consistent. Contributing vocabularies of these widely circulating yet often lower-cost materials will enhance the AAT’s efforts to be a more inclusive lexicon. The AAT vocabulary was built originally from the perspective of “western” art history as its foundation, a perspective that advanced a hierarchy of materials. The Dutch Textile Trade Project is working to expand the AAT’s textile vocabulary to include global trade textiles, broadening its material and geographical scope. Addressing racial and gender inequities in metadata standards is at the forefront of conversations in the digital humanities, and the Dutch Textile Trade Project seeks to contribute to this important work by expanding the aperture on vocabulary. These new AAT terms should engender a more democratized view of the textiles themselves and invite a more diverse array of interdisciplinary scholars to contribute to the vocabulary, not only elevating and expanding the terms but also inviting a more inclusive scholarly rank to them.

Conclusion

The visual glossary of the Dutch Textile Trade Project is a sustainable starting point—one that will grow and evolve just as the Getty AAT continues to do. Tethering these terms to an institutionally-managed controlled vocabulary that uses unique identifiers to manage names and name variants as they come to light affords this project some future-proofing by offering ongoing organizational support and maintenance. The terms presented reflect the current state of research, but the underlying architecture of the site allows for future name variants not currently reflected in the Dutch Textile Trade Project site to be captured and managed by the Getty. Importantly, this integrated approach to the study of historic textile terminology can deepen and broaden its utility by connecting and contextualizing these concepts for a wider and more diverse readership.