The subject of this article is the collector Henry Gurdon Marquand (1819–1902), banker and railroad financier, and a noted member of the burgeoning class of newly prosperous business magnates of Gilded Age New York. An exceptionally civic-minded patron, Marquand set out in the early 1880s to assemble a group of first-class Old Master paintings for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This paper explores Marquand’s acquisitions, especially the Flemish and Dutch paintings he bought. Focusing on Marquand’s 1889 gift of thirty-seven Old Masters to the museum—the first gift of its kind—this paper also considers Marquand’s aspirations, not only as a major private collector but especially as a leading donor to the institution, whose second president he became in 1889.

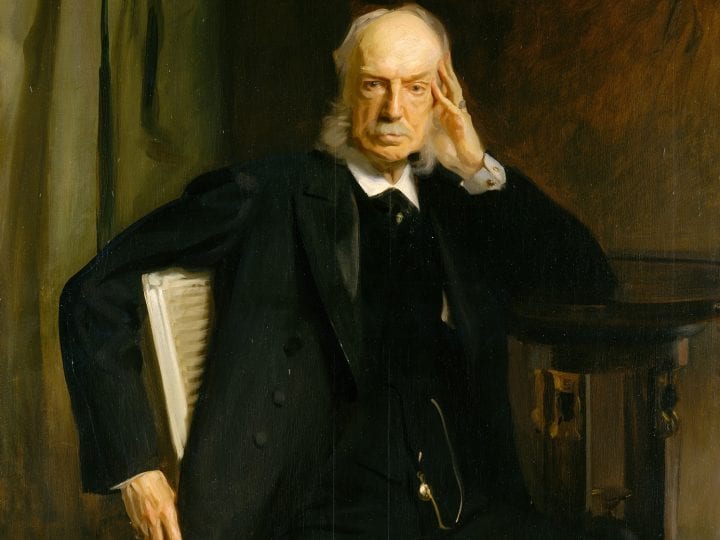

Henry Gurdon Marquand (fig. 1) was one of the great art collectors and philanthropists of late nineteenth-century New York.1 Ambitious, civic-minded, and unusually generous, he gave his support to the Metropolitan Museum of Art from its earliest days onward, making his mark both through his many gifts and his remarkable vision for the institution. A prominent tastemaker, Marquand was, according to his contemporaries, also responsible for the Old Master craze that swept New York in the final years of the nineteenth century. His tastes and aspirations have shaped the history of the Metropolitan Museum and, more indirectly, the history of many other museums in America.

A banker, broker, and railroad financier, Marquand was an eminent member of the emerging class of newly prosperous business magnates of Gilded Age New York. Born in the city in 1819, he left school when he was sixteen years old and started working in his family’s silversmithing firm, Marquand & Company. After his father’s death, in 1838, the firm was sold and Marquand went into various other branches of business, including real estate investment and banking. In 1868, he also became involved with the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad, serving as its vice-president from 1875 to 1881, and then as its president for a year. The sale, in December 1880, of twenty thousand shares of stock in the Railroad left Marquand with $1 million, then an enormous fortune.

Marquand was well traveled—he first visited Europe in 1843, when he was in his mid-twenties, and reportedly it was during this trip that he became interested in the arts. He began collecting art in the 1840s or 1850s, initially concentrating on contemporary paintings and decorative objects. Over the years, he built friendships with many artists, among them a large number of expatriate Americans, who also advised him on his art purchases. Marquand’s collecting and his interests in the arts were characterized by a strong sense of public purpose: he was, in 1869, a member of the so-called Provisional Committee to establish a museum of art in New York, becoming a trustee of the newly founded Metropolitan Museum in 1871 and its treasurer in 1882.

The museum’s founders, Marquand among them, aimed to assemble an encyclopaedic collection, comprising paintings and sculpture as well as decorative arts, and even industrial arts. Marquand not only made large financial donations to the institution—including, for example, in 1886, $10,000 for the acquisition of sculpture casts and, the following year, $30,000 for the endowment of a museum art school—but he also presented gifts to virtually every curatorial department. His first nonmonetary gift to the museum dates to 1879, when he donated a collection of pre-Columbian Native American ceramics, known as Mound-Builders pottery. Several other gifts followed, among these, in 1881, the donation of the Jules Charvet collection of so-called ancient glass. Marquand’s first gift of a painting took place that same year, when he donated John Trumbull’s Alexander Hamilton.2

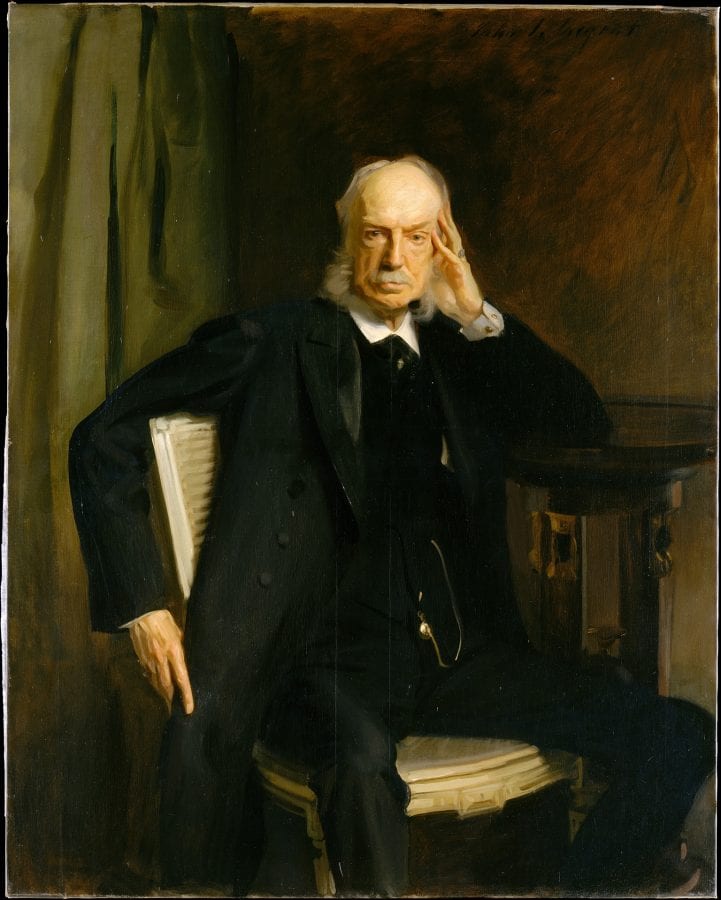

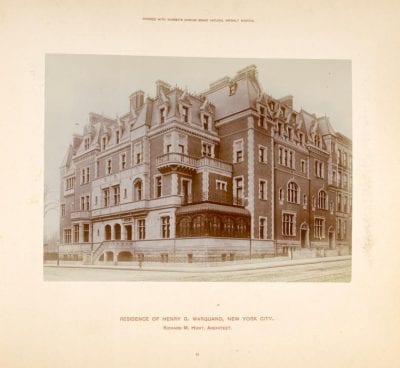

In the meantime, Marquand had also built a private picture collection, which, by the later 1880s, comprised a large and eclectic group of works, mostly British portraits, French landscapes, and contemporary British and American paintings . He kept his collection at his grand four-story mansion at 11 East Sixty-Eighth Street, on the corner of Madison Avenue, not far from “Millionaires’ Row” (fig. 2).3 The exterior of Marquand’s house, designed in the French Renaissance style by his friend Richard Morris Hunt, then New York’s most sought-after architect, was completed in 1884. Its interior, influenced by the Aesthetic Movement and executed in a variety of styles, took several years longer to finish. Unlike some other leading collectors’ residences in the city—for example, those of Alexander T. Stewart and William H. Vanderbilt—the mansion did not have a separate art gallery; Marquand’s many paintings, his sculptures, and other art objects formed an integral part of its interior decoration. The centerpiece of Marquand’s private collection was A Reading from Homer of 1885, a large history painting commissioned from Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.4

6But Marquand was also the owner of what can be described as a second collection.5 In the early 1880s, after his retirement from active business, he had assigned himself an extraordinary mission: in order to enhance the picture holdings of the fledgling Metropolitan Museum, he had set out to assemble a group of first-class Old Masters. After all, only a few Old Masters had been added to the group of 174 works—of varying quality—that had come to the Museum in 1871, as its founding collection, known as the “Purchase of 1871.” Marquand, as a contemporary later wrote, “felt sure that a group of paintings of the highest order would be unique and invaluable.”6

The domestic market for Old Masters was still small and Marquand, like most of his collecting contemporaries, bought the majority of his Old Masters in Europe. He did this with the help of a large network of agents and advisers, which included expatriate painters such as George Henry Boughton, Francis Davis Millet, and J. Alden Weir, as well as London dealers such as Martin Colnaghi, Thomas Humphry Ward, and Charles Deschamps. Marquand often profited from the dire financial circumstances of the Old World’s aristocrats, many of whom sold off their most esteemed artistic possessions in order to keep their estates. A strong contender in the market, he was willing to pay high prices for paintings he desired. In 1883, he purchased—for a steep $25,000—Portrait of a Man (fig. 3), perhaps the first authentic painting by Rembrandt to come to America.7 Rembrandt was arguably the most coveted Old Master on both sides of the Atlantic about this time, and Marquand’s acquisition may well have been inspired by the lack of a Rembrandt in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. As George Henry Boughton wrote to Marquand at the time, “by bringing such a magnificent example of such a splendid master to our country you have done every lover of art there a lasting service, for which they should be ever grateful.”8

Three years later, in 1886, Marquand bought the painting that many of his contemporaries considered the highlight among his Old Masters, Anthony van Dyck’s James Stuart (1612–1655), Duke of Richmond and Lennox (fig. 4). Van Dyck, like Rembrandt, was one of the most admired Old Masters in the Gilded Age, and Marquand paid an exorbitant price, $40,000, for the portrait. (Reportedly, the cost of the construction of his opulent mansion was $125,000). Among Marquand’s other notable Old Master acquisitions of the 1880s were, for example, Johannes Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (fig. 5), probably the first Vermeer to come to America; Filippo Lippi’s Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement, bought as a Masaccio (fig. 6); and Portrait of a Man, bought as a self-portrait by Velázquez though now considered a workshop piece, perhaps a self-portrait by Juan Bautista del Mazo.9

Over the years, several authors have written that Marquand’s Old Masters went straight to the Metropolitan Museum upon their arrival in America and never even entered his residence.10 In fact, that was not the case, as is evident from the observations of the critic Montezuma (pseudonym of Montague Marks), who visited Marquand’s mansion in 1887.11 In its entrance hall, Montezuma saw some of Marquand’s most prized Old Masters: on the left wall, van Dyck’s “splendid” portrait of James Stuart was flanked by Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man (see fig. 3) and a portrait presumably by Velázquez; on the opposite wall hung “two upright Constables.”12 Clearly, Marquand used the entrance hall as a showcase for some of his most precious acquisitions. Montezuma also visited the mansion’s music room, a gray-and-gold drawing room, also known as the Greek room, designed by Alma-Tadema in the neo-Greek–Roman style. Still unfinished, the room was already “much-talked-of,” as Montezuma noted. On its walls, he saw “many modern paintings” as well as “several old masters”—including “a Franz Hals, a Van der Meer of Delft, a Terborg, a Van der Meer of Leyden, and a portrait of a young lady, full of style and delightful in color by Gainsborough.”13 The residence was not open to the public.

In December 1888, eager to show his recent Old Master purchases to a larger audience, Marquand lent a group of thirty-seven works to the Metropolitan Museum, where they were exhibited in its new South Wing.14 The loan effected a sea change in the way New Yorkers—and, in a broader sense, Americans—were able to view art, as it introduced them directly to the works of some of the most celebrated Old Master painters, which until then only a fortunate few would have been able to see in person on their European travels. “Those who have seen the examples of Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Constable, Turner and other masters which are owned by Mr. Henry Marquand will appreciate the value of the opportunity offered by their public exhibition,” wrote the New-York Tribune on December 18, 1888, the day of the South Wing’s opening. “These paintings . . . furnish an illustration of great art such as we have not had before. We trust that it may not be injudicious to express a hope that these superb paintings may remain at the Museum.”15

The public’s enthusiastic response to the exhibition soon led to Marquand’s greatest act of philanthropy: On January 10, 1889, less than a month after he had lent his paintings, Marquand donated them to the Metropolitan Museum. In a letter to its Executive Committee, he wrote that he had noticed the interest with “sincere pleasure,” and announced that his pictures would be “of far greater service to the public to remain where they are, and in a public gallery, rather than in a private house.” Requesting that they be kept together “as much as practicable,” Marquand offered the works unconditionally to the museum, hoping that they would prove to be “of lasting service to the public.”16 A month later, he was elected the museum’s second president, a position he would keep until his death. Soon, a gallery on the museum’s second floor was named the Marquand Gallery (fig. 7).

It was Marquand’s wish that the American public, and artists in particular, benefit from his collecting efforts for years to come. At the same time, however, his charitable act was meant to serve as an example for his collecting peers, as Marquand felt compelled to use his riches to improve society and thus justify his expenditures on art. After all, as his acquaintance and fellow philanthropist Andrew Carnegie also argued in his essay “Wealth”—published in June 1889, months after Marquand made his gift—the best way of dealing with the phenomenon of wealth inequality was for the rich to give away their fortunes during their lifetimes, in such a manner that they would be redistributed responsibly and thoughtfully.17

Marquand’s generosity did not end with his great gift of 1889; for a short time, he continued buying pictures at a swift rate, donating two smaller groups to the Metropolitan Museum in 1890 and 1891, respectively. Included in these gifts were such works as Girl with Cherries, bought by Marquand as a Leonardo da Vinci, but now attributed to the master’s collaborator Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis; a small Lamentation, bought as by Jan van Eyck but now ascribed to Petrus Christus; and an excellent Frans Hals, Portrait of a Man.18 After 1891 Marquand made only a few more purchases for the museum; ironically, the market for Old Masters that he had helped to create only a decade earlier was now quickly becoming too expensive for him.

In 1893, Wilhelm Bode, the renowned director of Berlin’s Royal Gallery and one of Europe’s great tastemakers for Old Masters, came to America, where he visited several of its “new” museums—among these the Metropolitan Museum—as well as a number of private collections. Bode was “surprised” by what he saw in New York, as he confessed to the New York Times: “The public feeling for art, the architecture, the fortunes spent in public and private collections, the general interest in doing things that are magnificent, are the characteristics about which I constantly think.” Gifts were much more frequent in New York than in Berlin, Bode observed, and he was much impressed by what he saw at the Metropolitan Museum. As the New York Times wrote, “the treasures gathered by Mr. Marquand made [Bode’s] eyes scintillate.”19

After Marquand’s death, in 1902, the New York Times described him as “the steadiest and most persistent benefactor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” And indeed, it was through Marquand, and through others who followed his lead, that the Metropolitan Museum has become “really one of the museums not merely of the United States, but of the world,” as the New York Times wrote more than a century ago.20