This article proposes that Rembrandt created his Satire on Art Criticism in response to the 1644 publication Momenta Desultoria by Constantijn Huygens that included several disparaging epigrams about the artist’s portrait of Jacques de Gheyn III. This catalyst explains some of the peculiar inscriptions and illuminates many of the idiosyncratic visual aspects of the drawing.

Rembrandt’s motivation for creating his puzzling sketch A Satire on Art Criticism (fig. 1) in the Robert Lehman Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has yet to receive a satisfactory explanation.1 It is no wonder, since the state of finish is rudimentary and the scratchy annotations that might clarify the artist’s intentions defy transcription.2 Several scholars, including Jakob Rosenberg, Jan Emmens, and Ernst van de Wetering, have seen the sketch as a personal polemic made in response to criticism, but as yet no idea has adequately elucidated the circumstances that lie behind this apparently acrimonious drawing.3 While a full explanation of this unusual allegory and its context may still be elusive, and a complete consideration of the nuanced landscape of reception and criticism that surrounded Rembrandt is beyond the scope of this article, a proposal is presented here that the drawing was indeed stimulated by a specific criticism directed at the artist.

Without dwelling on the sheet’s attribution to Rembrandt, which has been unanimously supported in recent literature, it may be said that the peculiarities of the handling can perhaps be ascribed to the unusual circumstances that brought it into being.4 Its purpose is not readily apparent. It is unlikely to have been intended as a preparatory study for a painting, since Rembrandt rarely employed such allegorical imagery in paint, although a print may have been envisioned. It looks hastily composed, but a certain amount of forethought must have preceded its creation because the image blends allegorical motifs with contemporary representations, and it demonstrates a familiarity with traditional visual and literary themes of art criticism.

First, it is necessary to identify the figures and to clarify their actions. There are two main characters whose essential identification is generally agreed upon: a man at the far left with ass’s ears poking out of his hat is a foolish critic, while the crouching figure at the lower right is the artist whose work is being scrutinized by the critic and who replies by defecating.5 The gesturing critic holds a pipe in his left hand and motions toward two paintings that are placed before him, one lying on the ground and another standing vertically. The pipe and barrel are traditional vanitas elements, alluding to the fleeting and empty character of the critic’s words.6 The ass’s ears on the critic signify his foolishness and poor judgment.7 The Midas-like ears, particularly in the context of a slandered artist, and the snake wrapped around the arm of the critic, symbolizing envy, also relate to the tradition of the Calumny of Apelles.8 Artists often made use of this imagery when taking a shot at their critics–one recalls not only Apelles but also Michelangelo, who audaciously used this combination of a serpent and ass’s ears in his portrait of Biagio da Cesena at the base of the Last Judgment.9

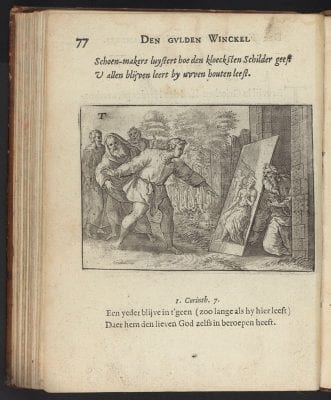

Turning now to the defecating figure, as Van de Wetering pointed out, Rembrandt gave considerable thought to the placement of the vertical panel, changing its position so that he seems to crouch behind the panel.10 This arrangement corresponds to the theme of Apelles and the shoemaker, another story of criticism and rebuttal, as seen in an emblem from Joos van den Vondel’s Den Gulden Winckel of 1613 (fig. 2). The crouching man wipes his bare behind with the pages of a book that lies before him. His actions do not draw the attention of any other figure, and he alone turns to address the viewer as if to comment upon the present action.

Among the remaining figures the most significant is the centrally placed person wearing a large chain necklace. I. Q. Van Regteren Altena, in correspondence with the Metropolitan Museum, and Emmens saw him as a bode or knecht (a guild servant). Egbert Haverkamp Begemann suggested that the chain might be a chain of honor, granted by royal patrons to worthy servants, and that this figure might also be a painter. If this is correct, then he may be seen as the type of painter who seeks the recognition of royalty and public critics, in contrast to the crouching figure who disdains such interest. A slightly different identification seems more likely, though: the figure could be the personification of painting, Pictura, one of whose attributes is a golden chain. In Rembrandt’s image, the jaw of this figure is rigidly drawn, which I take to be a shorthand indication of the band that covers Pictura’s mouth to indicate her role as silent poetry, as in the title-page personification from the 1644 Dutch edition of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (fig. 3).

Finally, standing directly behind the character with the chain is another person of indeterminate sex and debatable purpose. Haverkamp Begemann’s identification of the figure as Minerva fits with the pose and attributes and accords as well with a traditional role of the Goddess of Wisdom, that of protecting the arts from ignorance (as in a drawing by Federico Zuccaro [ca. 1541–1609], fig. 4).11 Rembrandt indicated a high helmet on her head, and she rests her right hand on her hip, elbow akimbo, while her left arm raises a shield. Minerva shields the critic from two men on the far right who wear contemporary clothing of the 1640s and perhaps embody the public-at-large.

A more precise interpretation of the drawing is dependent on deciphering the inscriptions, a task that for the most part has eluded scholars. The most easily understood line of the text is the one at the bottom of the sheet which reads “den tijt 1644” (literally, in the time 1644). This inscription is significant in dating the creation of the drawing, of course, but its form is highly unusual; i.e., it is not a date as normally seen accompanying a signature. The phrase seems to indicate that the event shown in the drawing refers to something topical that happened in that year. Several writers have seen it this way and attempted to relate the drawing to Rembrandt’s personal circumstances. Rosenberg saw the drawing as “coming at a time (1644) when the artist’s popularity began to wane.”12 Emmens tried to be more specific, identifying the critic as a portrait of Franciscus Junius, whose Der Schilder-konst der Oude (a Dutch translation of his De Pictura Veterum) appeared in 1641, but this suggestion has found little support in subsequent literature because the date of Junius’s book does not accord with the inscription on the drawing, and in any event Junius did not directly address Rembrandt. Neither do the writings about Rembrandt by J. J. Orlers, Philips Angel, or Joost van den Vondel seem to fit, as they were all published earlier and either praise the artist or deliver only the mildest criticism.

Other scholars have been content with a generic identification for the critic and have taken the scene to represent more of a climate of criticism rather than a specific incident. One could support this reasoning with reference to Samuel van Hoogstraten’s commentary expressing mixed feelings about Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, extolling its powerful presence amongst the militia pieces in the Kloveniersdoelen, while at the same time suggesting that it had been painted too dark.13 Even though his book was not published until 1678, it would come as no surprise if Van Hoogstraten’s remarks reflected sentiments expressed when the painting was first installed in 1642, since he was a pupil of Rembrandt at that time.

In addition to written criticism, we also know that Rembrandt was involved in a number of disputes with patrons regarding money, timeliness, style, likenesses, and decorum.14 It is serendipitous that these incidents are documented, and it is not at all unlikely that other major disputes went unrecorded or were not preserved.

I do believe the critic in the drawing was intended to depict a specific individual, however, both because of the peculiarity of the inscription and because the rendering of the critic, while certainly not portraiture in a pure sense, has a measure of specificity that one often sees in caricature. He is portrayed as a contemporary figure of significant status, wearing a gentleman’s vest with broad sleeves and a wide flat collar. A strap runs diagonally across his chest, indicating that he may have a sword behind him, and he wears a wide-brimmed hat. His pose is equally aristocratic, with the left elbow extended akimbo. Furthermore, even though he is perched on a barrel, his edge-of-the-seat, spread-leg sitting position was common for gentlemen of rank. There is a person who fits all of the relevant criteria: Constantijn Huygens.

Huygens was private secretary to Prince Frederik Hendrik of Orange, Stadhouder of the United Provinces.15 The secretary’s political influence was widespread, particularly in attaining accords with England and France while advocating the war against Spain. His greatest influence, however, was undoubtedly in cultural affairs. He was the Dutch embodiment of the gentleman courtier (honnête homme), espoused in international court circles of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His cultured erudition was vividly expressed in music and in poetry, where he exhibited equal facility in Dutch, Latin, and French, while his fluency in Italian and English is testified by his letters, diplomatic ventures, and literary translations. Because of his writings and advice to the prince on numerous commissions and acquisitions, Huygens is generally regarded as one of the most astute critics of art in the seventeenth century.

As early as 1629–30, Huygens recorded an autobiographical account of his life, including commentary on many contemporary painters in notes that went unpublished until the end of the nineteenth century.16 A prominent section was reserved for two young men of Leiden, Jan Lievens (1607–1674) and Rembrandt. Huygens’s economical and insightful characterizations of their respective artistic styles and aptitudes still resonate in today’s histories. In the midst of his praise, however, he lamented that Lievens and Rembrandt did not follow his advice, which he had also conveyed to Peter Paul Rubens, to keep a register of all their works, indicating “by what plan and what judgment they constructed, ordered and worked out each item.” Certainly had such a record been kept it would have rendered the present inquiry redundant.

More significant to the present study is Huygens’s opinion of these two young artists’ character when presented with criticism, and here he did not flatter. Huygens wrote of Lievens, “I used to reprehend that one fault of his–a danger risked not just once–namely, that he either flatly rejected every criticism or took it once admitted with a bad spirit because of a certain rigidity based on too much confidence in himself.” Huygens elaborated on one consequence of this stubbornness, as he saw it, with respect to both artists: “I can scarcely tear myself away from talk of such outstanding young men without turning again to that one fault for which I already censured Lievens–they are carelessly content with themselves and till now have not thought Italy of such great importance, though they need to spend a few months traveling there.” It is quite clear that Huygens thought these two young men, Lievens in particular, were insolent and defiant when it came to good counsel and criticism of their work.

Rembrandt’s relationship with Huygens is one of the most intriguing puzzles in Rembrandt research, because of its importance and because the facts available raise more questions than they answer. It is beyond the scope of this brief essay to consider the nuances of Huygens’s patronage, but certainly he had a hand in Rembrandt’s early court commissions, especially the series of Passion paintings made for the stadhouder. Rembrandt’s seven surviving letters to Huygens about these paintings reveal that he had delayed completing them for some time and that he had requested far greater remuneration than he was eventually granted. The letters do not demonstrate any open animosity between the two, even though Huygens declined to accept a large painting that Rembrandt offered him as a gift.17 It is generally believed that Huygens grew to dislike Rembrandt’s art, favoring instead the international classicizing styles newly introduced into the Republic, and by the 1640s he turned his attention increasingly to Flemish artists and Dutchmen with experience abroad.

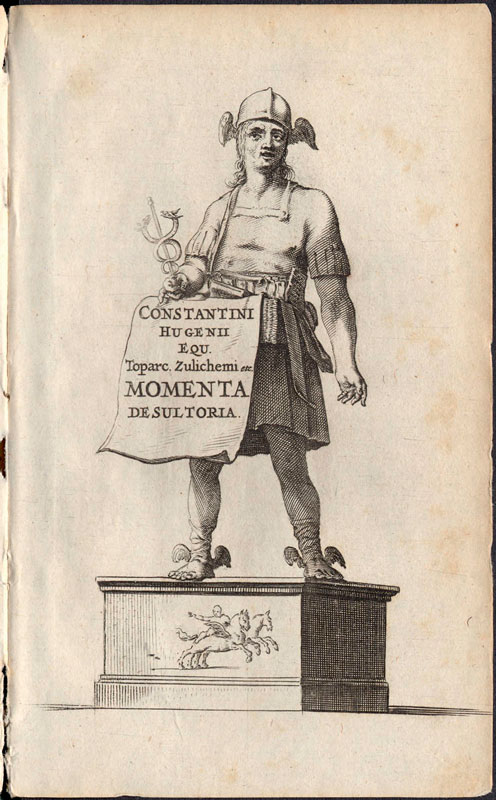

We can be more specific, however, with regard to the point of intersection with the Lehman drawing. In the year 1644, as scribbled by Rembrandt on the Satire on Art Criticism, a different and more candid sentiment expressed by Huygens about Rembrandt entered the public stage by its publication in Amsterdam. In a volume of his collected Latin poetry called Momenta desultoria, featuring a title page with an image of Mercury designed by Huygens himself (fig. 5), the secretary addressed Rembrandt’s Portrait of Jacques de Gheyn III (fig. 6) in seven brief epigrams. As Inge Broekman has recently pointed out, Huygens’s poetry, especially these exercises related to portraits, was primarily aimed at expanding and reinforcing his social network.18 He did not likely intend to insult Rembrandt but rather to glorify the sitter. De Gheyn, a painter and neighbor of Huygens in The Hague, also had close contacts with Rembrandt in the 1630s.19 These epigrams were originally penned in January and February of 1633, but they were kept private initially and were not published until eleven years later. For this reason, the publication date has gone largely unnoticed and has never before been tied to the Lehman drawing. The publication can hardly have escaped Rembrandt’s attention, however, and even though the poems were meant to be jokes, it is difficult to believe that he would have lightheartedly disregarded them.

The epigrams read as follows:

IN JACOBI GHEINIJ EFFIGIEM PLANE DISSIMILEM, JOCI

(On Jacob de Gheyn’s portrait, which is not like him at all; jokes)Talis Gheiniadae facies si forte fuisset

Talis Gheiniadae prorsus imago foret.

(If de Gheyn’s face had happened to look like this,

This would have been an exact portrait of de Gheyn.)(ALIUD)

Haereditatis patriae probus Pictor

Invidit assem Gheinio, creavitque,

Quem recreet semisse posthumum fratrem.

(The worthy painter has begrudged de Gheyn his father’s full inheritance, and has created a posthumous brother to gladden with the half of it.)(ALIUD)

Quos oculos, video sub imagine frontem?

Desine, spectator, quaerere, non memini.

(Whose eyes and whose face do I see in this portrait?

Stop your questions, Viewer, I cannot remember.)(ALIUD)

Gutta magis guttae similis fortasse reperta est,

Tam similis guttae non, puto, gutta fuit.

(Perhaps a drop has been found that more resembled a drop. I think a drop has never been so [little] like a drop as this.)(ALIUD)

Geiniadem tabulamque inter discriminis hanc est

Fabula quantillum distat ab historia.

(There is as little difference between de Gheyn and the painting as between myth and history.)(ALIUD)

Tantum tabella est, si tabella quae bella est,

At haec, tabella bella, bella fabella est.

(It is only a painting, though a lovely painting,

but this lovely painting is a lovely myth.)(ALIUD)

Cuius hic est vultus, tabulam si jure perculij

Quisque suam possit dicere, nemo sui?

(Whose face is this, that anyone can call his own for money, but no-one on the grounds of likeness?)

An eighth epigram was included in Huygens’s diary but was left out of the Momenta desultoria, and from this piece we can be certain that the portrait under ridicule was painted by Rembrandt:

(ALIUD)

Rembrantis est manus ista, gheinij vultus;

Mirare, lector, et iste Gheinius non est. Eod. die.

(This is the hand of Rembrandt, the face of de Gheyn; look in wonder, reader, it also is not de Gheyn. On the same day.)

These jocose word-plays (such as tabella, bella, and fabella in the sixth poem) are moderated slightly by their self-description as “jokes,” but they cannot be taken as flattering toward the artist in the least. To suggest that a portrait failed to capture the spirit, personality, or glories of a sitter was standard rhetoric, but to assert that a portrait failed to capture a likeness was another matter entirely, especially when conducted in the elitist form of disparaging Latin witticisms. Such public assaults on a single picture are rare in Dutch poetry and art criticism. When it came to publishing these poems, Huygens clearly tempered the impact of his banter by omitting the final epigram where Rembrandt’s name was mentioned. Still, the painter surely would have understood that he was the butt of the jokes.

In the Lehman Satire, the critic is dressed as a contemporary gentleman, as discussed above. Huygens’s status as secretary to the Prince of Orange and a knight in his own right make him an appropriate candidate for this clothing. Furthermore, the facial features of the critic are consistent with those of Huygens, whose visage is known from numerous contemporary portraits, including full-length portrait of 1627 by Thomas de Keyser (1596/97–1667) (fig. 7), where he is seated in a similar gentlemanly manner, and an engraving by Paulus Pontius (1603–1658) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) (fig. 8) distributed in the 1630s, where his features are likewise translated into a graphic medium. Huygens was consistently shown sporting a broad mustache and a trim stroke of beard, and his hair is shoulder length and slightly disheveled, just like the figure in the Lehman sketch. Furthermore, Rembrandt drew a pair of eyeglasses on the ground before the critic’s left foot, and Huygens bemoaned his own poor eyesight, returning to the issue several times in his autobiography.20 He wore glasses regularly from the time he was sixteen years old, but he was never depicted wearing them or with them by his side. Glasses were often ridiculed in Dutch literature and art, and by placing them on the ground Rembrandt reinforced the notion that the critic is blind and therefore unfit to judge art.

Even though the other inscriptions on the Satire are largely illegible, a portion of the two lines beneath the critic can be read: “dees . . . van d kunst / is [hortich?] gunst (this . . . of art/ is [contrary?] favor).”21 The rhyme kunst (art) / gunst (favor) was fairly common in Dutch poetry, and especially so in literature about the patronage of painting. Huygens’s position as both critic and patron poignantly corresponds to this inscription. The fact that Rembrandt made a rhyme reinforces the connection to poetry as the source of his grievance. The paintings being scrutinized in Rembrandt’s drawing appear to be portraits, especially the one on the ground, just as Huygens’s remarks about Rembrandt were directed at a portrait. Moreover, Rembrandt’s defecating artist may have been directly inspired by a particular aspect of Huygens’s poetry. In the fourth epigram, the secretary made a play on the word guttae (droplet). In humorous contexts this word commonly referred to dung, and Rembrandt may well have been turning the tables on the poet with a scatological pun of his own.

Finally, the most direct and convincing connection between Rembrandt’s drawing and Huygens’s Momenta desultoria is the 1644 date. The question at the heart of this examination has been whether Rembrandt’s Satire was prompted by a specific criticism directed at him. The publication of Huygens’s epigrams fits the timing and accords with the clues provided in the drawing itself. If this hypothesis is correct, such a catalyst helps to explain the content and overall character of the drawing. In a situation like this, Rembrandt could not complain to the guild or other arbiters, nor could he insist on being paid his due or assert the quality of his completed product, as he did in other disputes. The only rebuttal open to Rembrandt was to reply in kind to Huygens’s paragone between painting and poetry, to create an equally witty ut pictura poesis of his own, in his own medium. In the end, however, Rembrandt’s temper seems to have died down and the drawing remained a private statement, never distributed publicly, and never recognized in later times for the specific circumstances that brought it about.