Rembrandt’s use of works by earlier artists as formal inspiration for his own is well-known. This essay examines Rembrandt’s little-recognized appropriation of poses, compositions, and even methods of handling light and dark from Martin Schongauer’s engraving Christ Carrying the Cross. Rembrandt returned to Schongauer’s print at various moments in his career, most notably for the creation of one of his most ambitious etchings, The Hundred Guilder Print.

Rembrandt’s use of works by earlier artists as formal inspiration for his own is well-known.1 We often recognize in his drawings, prints, and paintings motifs from the Renaissance compositions of such artists as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Lucas van Leyden (ca. 1494–1533), and Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431–1506), among others, as well as from works by such seventeenth-century artists as Jacques Callot (1592–1635) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). In contrast, works by fifteenth-century artists like Martin Schongauer (ca. 1420–1491), such as his masterpiece of early engraving, Christ Carrying the Cross (Lehrs 9) (fig. 1), with its nervous, animated drapery, unstable poses, and teetering setting, may be among the last pieces that come to mind when considering sources for Rembrandt’s imagery.2 Peter Schatborn, however, recognized one instance in which Rembrandt turned to Schongauer for inspiration. Rembrandt looked at Christ Carrying the Cross for the figure of Christ in a drawing of the same subject in Berlin (Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. no. Kdz 1554). In that sheet, which dates to ca. 1635, Rembrandt took over the main motif and conceived a Christ upon hands and knees similarly weighed down by the cross.3 Rembrandt’s inventory of 1656 indicates that he owned prints by Schongauer, so it would not be all that surprising to find that, on occasion, he would have drawn inspiration from works by his great predecessor in printmaking.4 This essay proposes that Rembrandt consulted Schongauer’s work, and specifically the Christ Carrying the Cross, often and at various moments in his career. It also proposes that Rembrandt looked to this engraving not only for specific compositional motifs but also as a model for variations in handling and for strategizing the depiction of similar large multifigured compositions. It influenced most notably the creation of one of his most ambitious etchings, The Hundred Guilder Print, ca.1648 (Hollstein 74) (fig. 2).5

The Hundred Guilder Print is among Rembrandt’s most engaging and complex compositions. The artist wove together individual episodes of the Gospel of St. Matthew to illustrate the entirety of chapter 19 in a horizontal format. He conceived an exquisite puzzle of darks against lights and lights against darks that draws the eye across the image.6 The figures progress into the composition from the area under the arch on the right toward the center, where Christ anchors the scene. Throughout the piece, the degree of handling shifts from figures in bright light, depicted in almost pure outline, to ones in shadow, heavily worked in etching and drypoint burr. Two states of the print exist, but the differences between them are minor.7 It is generally thought that Rembrandt worked on the etching over a period of several years. The many visible adjustments to figures and background, evident already in the first state, indicate that Rembrandt considered numerous variations to the image before the impressions of the currently recognized first state were printed. For instance, residual lines indicate that the man in the left background, who wears a skullcap was originally wearing a turban and his hand was raised (see fig. 10). Additionally, Christ’s left arm, which was once pointed down, is now raised, and the woman carrying the baby in front of him was first positioned further to the right (fig. 3). Several drawings associated with the print have survived, and all of these relate to the group just to the right of Christ, but Rembrandt’s thought process in assembling the rest of the image has remained unclear.8 Christopher White conceded that only a few generally relatable earlier sources have been identified, ranging from Leonardo (1452-1519) to Annibale Carracci (1560–1609), as well as Lucas van Leyden.9 Schongauer’s large and masterful Christ Carrying the Cross, however, offers more convincing evidence as a source for borrowing as he conceived the etching.

The clearest evidence for Rembrandt’s reliance on Schongauer’s engraving can be found in correspondences between figural and background motifs in both prints. Both display a boy viewed from the back with a dog at his feet at the bottom left. The stance of that boy in the Schongauer–upright, his feet turned out, one slightly in front of the other (fig. 4)–seems to have influenced the position of the feet of the turbanned woman holding a child on the left of Christ in Rembrandt’s etching. She also turns her back to the viewer and stands with one foot bent in front of the other, her right arm crooked to cradle the infant. The lightly indicated tassle on her back and belt at her waist correspond to the tassle and belt on the boy. This woman can be seen, in fact, as having been inspired by two figures in the Schongauer, not only the small boy but also the man with a turban just to the right of Christ who bends his leg and arm in similar ways (fig. 5). Rembrandt seems to have also referenced the braid that emerges from the man’s turban in the piece of cloth that falls from the woman’s headdress. In another example, on the right of Rembrandt’s etching an old blind man leaning on a stick is helped by a woman whose face appears slightly lower and to the far side of his (fig. 6).10 A parallel pairing can be found in Schongauer’s print on the right, where a man leans on a walking stick and the head of a boy appears to his far side, just slightly lower than his head (fig. 7).

This last example indicates that Rembrandt looked to Schongauer not merely as a resource for poses but also as a reference for ways of clustering figures within a larger mass. He created few compositions that include large numbers of figures. It should not be surprising to find that Rembrandt might have examined the work of earlier masters such as Schongauer to see how they might have handled similar compositional challenges.

The group of three Pharisees engaged in discussion in the left background of Rembrandt’s etching suggests as well that he consulted Schongauer’s engraving in just this way. The background group is composed of a row of men. The three main protagonists among them consist of a bearded man on the left wearing a skullcap, depicted in strict profile, who is in discussion with another man to the right, who sports a large beret and leans over as he turns his head toward the first. A third man, just to their right, bends over to listen in to their conversation. Ludwig Münz suggested with reason that two of the figures relate to a pair leaning on a ledge in the background of Lucas van Leyden’s print The Adoration of the Magi (New Hollstein 37) (fig. 8).11 It seems quite likely, however, that the Schongauer was the initial source. Rembrandt’s cluster of three men, two discussing and another looking on, corresponds in a general way to the three men on horseback in the upper right of Schongauer’s print (fig. 9). There, we see, in reverse order, a bearded man wearing a turban in strict profile in discussion with another who sports a beard and a large pointed hood. To their left, another man turns to listen in on their conversation; in other words, the same combination of two men in conversation and a third listening.

The connection between the figures in the Rembrandt and the Schongauer becomes more evident when we examine the print more closely. An early but unevenly wiped impression of the second state in the British Museum allows a clear view of some of Rembrandt’s pentimenti, which are often obscured in more richly printed ones (fig. 10).12 A careful examination of that impression reveals that Rembrandt’s original conception for the profile figure with a skullcap was of a man wearing a large turban. Rembrandt changed his mind about the headdress and carefully hatched over the turban, the outline of which is visible in the first state of the print. The deleted turban relates the figure in profile to the corresponding one in Schongauer’s engraving and, granted, also to the one in the Lucas print, both of whom wear turbans of slightly differing shapes. The large rounded shape of the turban that juts well past the forehead visible in the Rembrandt, however, comes closer to that in the Schongauer. Another detail points us to the German engraving as a source. As mentioned above, Rembrandt adjusted the gesture of this man’s right hand at some point before he printed the first state. The initial raised position of the hand reflects that of the right hand of Schongauer’s man in a turban. Rembrandt then redrew it so that the hand now points downward, much as in the man leaning on the ledge in Lucas’s engraving. Perhaps he first turned to Schongauer for inspiration and then looked further to Lucas as he adjusted his initial conception.

One peculiar element that appears in The Hundred Guilder Print is the dark shape in the background behind Christ. This form is more or less the shape of a brimmed hat that is tall and flat in the center and juts out at the bottom on the right and left. Its role, aside from bringing further attention to Christ, is unclear. It does not have enough depth to be a cave and is a bit hard-edged to have been intended as a shadow, but what else it might be is not immediately evident. Its peculiar shape may have its roots in the Schongauer engraving. There, Christ is placed directly beneath some dark arched mountains that help to isolate and highlight this central figure within the bustling throng that surrounds him. This cluster of monoliths behind Christ in Schongauer’s engraving, wide at the bottom and less so at the top and positioned substantially above Christ’s head, seems to have been taken up by Rembrandt as a way of giving focus to his own figure of Christ.13

Beyond the mere connections of figures and surroundings, Rembrandt’s etching shares a more general compositional affinity with Schongauer’s engraving. While the two prints differ in subject, their basic schemes are similar. Schongauer’s engraving is a large horizontal image depicting a procession that moves from right to left. Despite the views into the distance, the entire scene is rather two-dimensional and close to the surface of the picture plane. Jam-packed with figures, it is anchored at its center by Christ, who draws the viewer’s attention with his inescapable stare. Similarly, Rembrandt’s etching depicts an assemblage of many figures, and the group on the right proceeds in from the side. It is likewise anchored by Christ at the center. Like Schongauer’s scene, Rembrandt’s also occupies primarily a single plane.

Furthermore, Schongauer’s engraving can be viewed as a carefully mastered exercise in the alternation of darks and lights within a horizontal composition. The highly defined figures on horseback on the right are placed in front of an area of the sky and landscape that are defined merely by outline. In contrast, the figures in the background on the left are mainly created from outlines, and they are placed in front of the hatched section of the sky. And so it goes throughout the scene, densely hatched areas appear in front of less hatched ones, guiding the eye across the scene by means of this alternation. Rembrandt, clearly fascinated by effects of chiaroscuro from his earliest works, seems to have fixed on this element in Schongauer’s print. In The Hundred Guilder Print, he created a similar alternation of juxtaposed dark and light areas. In the left background, the figures in bright light are delineated merely by outline placed against a dark background, while figures on the right are more densely hatched but set against areas of light. On the far right, where the dark figures proceed in through the archway, there is light coming in from behind them, and so forth. Describing figures in pure outline to suggest bright light is a method that we closely associate with Rembrandt, but it seems to have had its roots in the artist’s study of Schongauer.

A closer look at the pentimenti suggests that Rembrandt might initially have been considering even more correspondences with Schongauer’s print, which he later reconsidered. For instance, an examination of the scumbling in the lightly etched background on the left of The Hundred Guilder Print reveals a series of horizontal curves that have been etched over. Could they have once indicated a hilled landscape similar to the ones in the right and left backgrounds of Schongauer’s engraving? Additionally, to the right of the dark shape above Christ, Rembrandt sketched some dangling branches with leaves. Their appearance and placement evoke the cluster of clouds that divides the dark and light areas of the sky in Schongauer’s piece. Should this theory prove correct, one might read a certain degree of uncertainty on Rembrandt’s part in this strong overall reliance on Schongauer’s composition as he began to compose this large and complex print.

Rembrandt may have consulted one further print by Schongauer in delineating the pensive rich man on the left who questions whether to give up his riches to follow Christ (fig. 11). His pose, seated with his hand over his face, resembles in many ways that of Schongauer’s peasant in A Shield with Wings Conjoined in Base, Supported by a Peasant (Lehrs 101) (fig. 12). While Rembrandt’s inventory does not reveal which specific prints by Schongauer were in his collection, he no doubt had several and it would have been natural for him to peruse the works housed together.

A number of other pieces by Rembrandt show the influence of Schongauer’s Christ Carrying the Cross. In the etching Abraham and Isaac, 1645 (Hollstein 34) (fig. 13) we find a turbanned Abraham in strict profile, raising his far hand in speech. His head with its beard turned up bears some resemblance again to the turbanned figure in profile on horseback who raises his far hand on the right of the Schongauer (see fig. 9). A possible relationship between these two prints becomes even more tantalizing if we compare the figure of Isaac sporting a pageboy haircut and a calf-length tunic to the boy with the dog in the bottom left of the Schongauer, who, while not identically posed, does display a similar haircut and dress (see fig. 4). The two figures in Schongauer’s print are situated on opposite sides of the composition, yet their lines of sight are linked as though they are looking at each other, as the figures do more directly in the Abraham and Isaac. Here Rembrandt extracted a figural group of sorts from Schongauer and intensified their psychological interaction.

His next large multifigured print, Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves (The Three Crosses), 1653 (Hollstein 78) (fig. 14), also relies on Schongauer. As in The Hundred Guilder Print, Rembrandt’s treatment of figures here varies from those highly finished with hatching to those suggested merely by outlines. Furthermore, the soldiers on horseback with their spears raised to the left of the cross seem to have been loosely inspired by the figures on horseback on the right of Schongauer’s print. In particular, the horse with a raised leg facing left in the Rembrandt group bears a strong resemblance in pose to the foremost horse among Schongauer’s mounted horsemen. In addition, the group of figures gathered around the fainting Virgin to the right of the cross refers to a similar group around the fainting Mary in the far left background of Schongauer’s print.

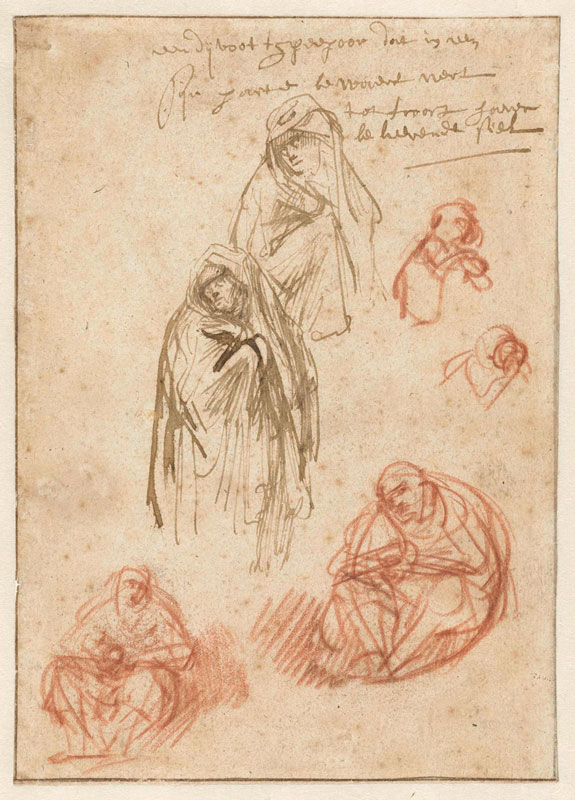

The works mentioned above all date to the 1640s, but there is evidence that Rembrandt looked at Schongauer much earlier as well. In addition to the drawing in Berlin touched upon at the start of this essay, there is the Sheet of Studies of Grieving Mary, 1635–36 (fig. 15) of about the same time, considered a study for Rembrandt’s painted Entombment (Pinakothek, Munich).14 At the top of the sheet are two figures of Mary drawn in brown ink. In both, she is wrapped in a cloak, which covers her head and one hand, and her head twists in the opposite direction of her body. This figure closely resembles in reverse Schongauer’s Mary, who stands in the left background just to the right of the horse with a braided tail (fig. 16).

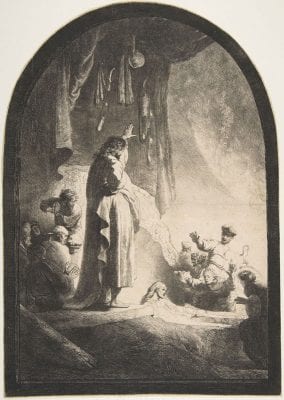

Another possible use of the Schongauer by Rembrandt, one that admittedly requires more of a leap than those mentioned above, may be found in his early etching, The Raising of Lazarus, ca. 1632 (fig. 17). In this print, Christ looms over the tomb with his back to the viewer, one arm raised on the far side of his head and the other arm bent at the waist, where a swathe of drapery gathers and billows behind him. This unusual pose, the far arm raised and the other arm bent, along with the swathe of drapery that waves behind, comes quite close to the figure of the man holding a rope just to the right of Christ in Schongauer’s print (see fig. 5). If this connection is correct, it may add a further piece of evidence to the discussion of the ordering of several related works, the painting and etching by Jan Lievens and Rembrandt’s painting of the same subject (Los Angeles County Museum of Art).15 Rembrandt’s painting depicts Christ with one hand raised and the other on his hip but viewed facing forward. Could the etching pre–date the painting?

Whether one accepts this last example or not, it is clear that, from a relatively early point in his career, Rembrandt consulted Schongauer’s work, and specifically Christ Carrying the Cross, and that the print continued to interest him over several decades. This should hardly be surprising, as it was one of the great masterpieces of printmaking which preceded him. It offered a wonderful array of figures in oriental costume that must have appealed to Rembrandt as he created his own biblical scenes. Yet, he did not so much look to Schongauer for exotic costumes as he did for poses, compositional ideas, and methods of handling light and dark in print. These borrowings were meant as blueprints, starting points, which Rembrandt would rethink and redraw as he further considered the composition. In early work, his use of sources seems to have focused on specific poses and he chose sources that related in subject to the work that he was in the process of creating, while in later ones he was intrigued instead by general compositional solutions to be found in the engraving, such as the dispersal of light and dark and methods of clustering and interrelating figures. Schongauer’s lightweight, unsteady figures full of Gothic movement at first hardly seem the stuff to have inspired Rembrandt’s solid figures seemingly based on everyday life studies. Yet this image, chock-full of exotic people both rich and poor, who noisily interact with each other, seems to have spoken to Rembrandt’s own artistic interests at various stages in his career. No doubt further references to Schongauer’s print within his oeuvre can be identified, and they should reveal more about Rembrandt’s borrowings from unexpected works and how his close study of earlier masters infused his own art.16