Three children play at the center of the Amsterdam Holy Kinship, which is attributed to Geertgen tot Sint Jans or his workshop. This seemingly quotidian subject is remarkable because it shows future martyrs engaged in a game of make-believe using the implements of their torments. In this paper, I argue that the activity occupying the boys offers an invitation to spiritual play that addressed viewers and asked them to find joy in the promise of God’s divine mercy and justice despite life’s hardships. Given the subject matter and the identity of the artist’s primary employer, it is probable that the audience included the Knights of St. John Hospitaller, an order of crusading monks, also known as the Johanniters, in Haarlem. The invitation offered in the panel not only addressed the daily work of being a monk but also offered encouragement to the Haarlem knights during a controversial period.

The Holy Kinship in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, usually attributed to Geertgen tot Sint Jans (fig. 1), depicts the interior of a church bustling with activity. In the nave, young mothers care for their infants, pious women attend to their devotions, small clusters of men stand in quiet conversation, an altar boy ensures that all the candles on the rood screen have been extinguished, and a trio of well-behaved children plays. The figures assembled here do not attend a Mass but, instead, appear to inhabit the church as a communal space in which everyday, albeit pious, activities take place. That a gathering like this should be depicted is not surprising as churches often acted as social meeting places in the late Middle Ages and early modern period. This particular group seems quite at home in the space, and the familiarity with which they treat the sanctuary raises three related questions: who are these people, which church is this, and what might the image have meant to its likely patrons?

Each of the figures depicted in the image, including the altar boy, belong to Christ’s extended family. Anna, the Virgin Mary, Elizabeth, Mary Cleophas, and Mary Salomas, along with their husbands and children, constitute the so-called Holy Kinship. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Christian belief held that Christ’s closest disciples were his cousins, who were the products of Anna’s trinubium (three marriages).1 The interior depicted in the panel cannot be identified definitively. The view onto a walled garden or orchard visible in the left middle ground and the sacristy space shown to the right of the nave may be indications that the sanctuary is an idealized version of the Church of St. John in Haarlem.2 Although there is some continued dispute over the identity of the painter, recent scholarship holds that the panel was executed by someone in the atelier of Geertgen tot Sint Jans, perhaps the master himself, who worked for the Knights of St. John Hospitaller in Haarlem at the time of the painting’s completion.3 In addition, not only does the architecture bear some resemblance to the Church of St. John, the image also gives the young Baptist (patron saint of the Johanniters) a place of prominence in the foreground. If the image indeed makes reference to the Church of St. John, then the Haarlem branch of the Knights Hospitaller would be a strong candidate for its commission. The compositional choices in the panel seem directed toward satisfying this particular group’s preferences, a point to which I will return later.4

The theme of the Holy Kinship was well established by the time this panel was painted. Other versions, such as an anonymous Holy Kinship from 1470 (Sint-Servaaskerk, Maastricht), or the rendition by the Master of 1473 (St. Maria zur Wiese, Soest), show Anna’s family gathered together. The adults and children in both these panels, like those in the Amsterdam version, display the quiet dignity expected of future saints and martyrs. Unlike these panels, however, the Amsterdam painting places a scene of children interacting with various objects near the center of the image. The three boys (Simon, James the Greater, and John the Evangelist) engage in, what Johan Huizinga might have termed, a serious game of make-believe in which they occupy themselves with the implements of their future deaths.5 Rather than the objects simply being signs for identifying each figure, or morbid prefigurations of their future torments, the scene appears to show children absorbed in a bit of recreation. This differs from the boys depicted in the 1470 rendition, who primarily are immersed in their reading, and from the three youngsters in the foreground of the 1473 version, who hold, but do not necessarily acknowledge, their attributes.6 While the concept of martyrs at play seems out of keeping with the seriousness that their sacrifices demanded, the activity enacted at the center of the panel does not diminish the gravity of their fates. The boys in the Amsterdam panel, for example, differ from the children playing with books of hours in Quentin Massy’s Saint Anne Altarpiece of 1507–8 (fig. 2). In Massy’s rendition, one of the youngsters apparently has torn pages out of the manuscript he handles and in doing so acts more like an undisciplined child than a future saint and martyr.

Other scholars have provided compelling interpretations of the Amsterdam Holy Kinship as a meditation on the sacrifice of Christ, a complex explanation of the Eucharist, an object involved in the ongoing debate over the Immaculate Conception, and a variation on the theme of the Ecce Agnus Dei.7 The analysis that I offer here works in combination with these already established readings. My aim in this paper is to nuance our understanding of the work by delving into a motif running parallel to the main subject of the image (i.e., the boys engaged in a game of make-believe). In what follows, I argue that the activity which occupies the boys at the center of the painting is an invitation to engage in a pleasurable spiritual exercise which was addressed the panel’s patrons and encouraged them to maintain confidence in the hope of eternal salvation despite life’s hardships. This invitation to holy play–a form of recreation that helped to inculcate virtue–was particularly important for the Knights of St. John in the period around the panel’s creation.

Veneration of Anna in the North

According to dendrochronological analysis carried out in 2001 during the panel’s restoration, the Holy Kinship was painted, at the earliest, in 1496.8 This date is significant as it places the panel’s creation during the heyday of the cult of Anna in northern Europe (ca. 1490–1520).9 This time frame coincides with the production of a number of Latin and vernacular tracts dedicated to the saint and her family written and printed in the regions containing modern-day Germany and the Low Countries. These tracts, the confraternities that sprang up with them, and the imagery created in concert with the cult spread throughout the north. The city of Strasbourg was an epicenter for this veneration.10 The Knights of St. John maintained a commandery in that city, which may have acted as a conduit for Anna devotion among other houses of the order.11 Strasbourg was not the only possible point of contact however. Paris, Bruges, Ghent, and Leuven also contributed to the dissemination of the cult.12 For devotees, one great benefit of venerating Anna was the possibility of being counted as a member of her family. Notionally, the Virgin became the votary’s “sister” and Christ became a “nephew.” In other words, the saints produced by Anna’s three marriages were no longer remote women and men who occasionally granted favors, they were close members of the family to whom the votary could turn whenever necessary.13 The Johanniters already had one association with the family of Anna thanks to their patron saint, John the Baptist, son of Anna’s niece Elizabeth. While the monks at St. John’s in Haarlem might simply have venerated John, the popularity of the cult of Anna would have made it appealing to turn to the rest of her family.

Anna veneration was widely available to the faithful and appeared in the works of Jacopo de Voragine, Ludolf of Saxony, and Jean Gerson–well-known authors who were represented in the Haarlem commandery’s library.14 Further, members of the houses of Valois and Hapsburg, with whom the Johanniters had a special bond, were ardent members of the Brotherhood of Anna.15 Charles the Bold, and his predecessors, belonged to the Brotherhood in Ghent. This particular organization was important for the Knights of St. John because their founder, Godfrey of Bouillon, had donated the relic of Anna that was its centerpiece.16 Maximilian I, the driving force behind recent social and political changes in the Low Countries, was also an ardent devotee of Anna. Not only was he a member of the Ghent brotherhood, he also attended a consecration of the order in Worms in 1496 and had an image of Anna-with-the-Three (i.e., her trinubium) emblazoned on the imperial banner.17 Showing veneration for the saint may have been a means of asserting the Haarlem house’s loyalty to the Burgundian dukes, which given the events of 1491–92 (which I will discuss in more detail later) may have been to the knights’ social and political advantage.

One of the main reasons for the cult’s popularity, though, was the belief that the saint had the ability to change one’s fortunes.18 The Johanniters may have seen a particular benefit in this aspect of Anna veneration. The period leading to 1496 was tumultuous for the Knights of St. John in general and for the Haarlem house in particular. The ever-present threat from the Ottomans, as well as other events, tested the strength and commitment of the order. The cost of defending the Holy Land, and especially the knights’ stronghold on Rhodes was enormous. After withstanding a siege in 1480, the fortifications on the island were in shambles. To raise funds, the Grand Master decreed that all houses in the order must send money. Around 1482, the commander of the Church of St. John in Haarlem (Jan Willem Janszoon) responded to this request by seeking to make use of all the indulgences granted to the order by various popes. In 1487, the Haarlem commandery received support from David of Burgundy, bishop of Utrecht, who drafted a letter giving the Johanniters broad rights to sell those indulgences.19 This, however, proved to be a point of contention with the other churches in Haarlem, especially the main parish church of St. Bavo. Not only did the pastor at St. Bavo refuse to participate, he also actively tore down the advertisements for the indulgences that the knights offered and publicly denounced the commander as a “deceiver of souls” from the pulpit.20 The dispute between these religious houses endured until the parliament in Mechelen ended the disagreement by ruling in favor of the knights (ca. 1500).

In addition to the need to support the priory in Rhodes and the ongoing dispute with the pastor at St. Bavo’s, the Haarlem house along with every other establishment in the city was effected by the “Bread and Cheese Revolt” of 1491–92. Coming on the heels of the end of the war between the competing political factions known as the Hooks and the Cods, the revolt injected more instability into a region already in social, political, and economic upheaval. The food shortages that resulted from droughts and local conflicts, as well as the ducal devaluation of currency (up to 66 percent) in 1489, had a chilling effect on the economy.21 When Maximilian demanded a new tax for keeping his armies in the field–the so-called Ruitergeld–the populace in North Holland reached a tipping point. In 1491, a protest broke out against the tax in Alkmaar and quickly spread beyond that city to Haarlem and, eventually, Leiden. When the uprising reached Haarlem in early 1492, the city initially held off the rebels. With the aid of fifth columnists, however, the mob made its way into the city through the Kruispoort. They moved along the Kruisstraat, which ran behind the commandery, to the nearby Groote Markt. Once they reached Haarlem’s center, they stormed city hall (fig. 3) and killed three people, including Claes van Ruyven, who was tax collector for Kennemerland. According to legend, one of the rebels (Walich Dirkszoon) cut up van Ruyven’s body and sent it to the dead man’s wife in a trunk along with a morbid poem.22 The mob then turned its attention to the homes of wealthy citizens and to local institutions.

Maximilian instructed Albert III, duke of Saxony, whom he had left in charge in his absence to quell the revolt. Albert made ample use of German mercenaries and stopped the rebellion in late 1492. The consequences were severe, especially for the citizens of Alkmaar and Haarlem, because Albert held them all responsible, even those who were not part of the mob. He removed all privileges and rights and made both cities totally subservient to his command. To recoup the money expended quashing the rebellion, Albert demanded 24,000 golden St. Andrews-guilders. In addition, he held the citizens of Haarlem responsible for van Ruyven’s death and ordered them to erect a memorial window in the church of St. Bavo and to pay restitution to the tax collector’s widow.23 Meeting these demands resulted in a new series of taxes on all goods in the city. These increased costs, in turn, drove a large portion of the population to leave town, which put even greater burdens on those left behind.24

As a powerful religious institution, and the legal possession of an internationally recognized principality, the commandery of St. John likely had some immunity from the taxes levied across Haarlem, though it is difficult to say how insulated they were. Absorbing the increased costs of goods not produced on the commandery’s grounds, for example, would have been an added burden on their coffers.25 In addition, a decree issued by the city council in 1496 exacerbated the Johanniters’ financial positions. Specifically, the council prohibited the alienation of inheritable property through gifts to religious institutions by stating that henceforth no one, whomever he may be, either through testament or otherwise, will be allowed to instruct, remit, sell, or transfer in any manner any houses or inheritances within the aforementioned city of Haarlem to any convents, beguinages, or monasteries standing within this city.26

This was not the first time the city council had worried about the habit of lay people giving churches and monasteries gifts of land, houses, livestock, and cash, often to the detriment of their heirs as well as to the city’s tax receipts. This particular prohibition, in fact, was originally issued in 1440 but was not strictly enforced. The financial woes facing the city in 1496 made it a priority to reiterate the law as a means of protecting its tax base. The fine for violating the law was rather steep–60 pounds for each infraction–and it is unclear from the statute’s wording who (the donor, the receiving institution, or both) was responsible for paying it.27 The Haarlem commandery had a long history of accepting such gifts and through them had built a substantial portfolio of income properties that helped support the monks.28 This prohibition, from which the knights had no exemption, removed one of the Haarlem house’s major sources of income. When coupled with higher prices on goods throughout the city and the drop in money generated by indulgences, thanks to the ongoing dispute with the priests at St. Bavo, the economic losses caused by the enforcement of this statute may have strained the commandery’s resources. Considering the financial hardships and social upheavals that hit all Haarlemers, plus the conflicts recently endured by the knights themselves, the cult of Anna’s role in overcoming past misfortunes may have been, from the Johanniters’ point of view, particularly attractive.29

Variations in Form and Content

The Amsterdam Holy Kinship offers a fairly typical rendition of the subject but differs subtly from other versions. In part this was because there was no fixed orthodoxy for depicting Christ’s extended family.30 As a result, the Amsterdam composition includes two significant points of departure that are worth closer inspection. These differences potentially shed light on how this particular version of the subject matter may have addressed the contemporary concerns facing the Knights of St. John

The first variation is the prominence afforded Elizabeth and John the Baptist, which seems to be a straightforward matter of adjusting the subject to meet the specifications of the panel’s most likely patrons, the Johanniters. John the Baptist was the patron saint of the Knights of St. John and, unlike other versions of the Holy Kinship, he and his mother Elizabeth are featured prominently in the foreground in the Amsterdam rendition. Elizabeth, clothed in expensive garments, is equal in size and placement to the Virgin and Anna. John emphatically points toward the Christ Child, underscoring his role as the Messiah’s forerunner, and Christ returns that gesture by reaching toward his cousin.

Records regarding the image are scarce and archival traces of the original patron no longer exist. Recent scholarship argues for the Amsterdam panel having been housed either in the Church of St. John or in the hospice located on the commandery’s grounds. While it is difficult to pinpoint the panel’s original location with any certainty, it seems more likely that it was housed in the main church rather than in the hospital.31 I base this conclusion on the specific manner in which the image addresses the monks rather than their guests in the hospice. The location normally posited for the panel is the Heemsteder Chapel located in the transept of the Church of St. John. The chapel was dedicated to Saints Simon and Jude in honor of Saint Anna.32 While Anna, Simon, and Jude are all present in the Amsterdam Holy Kinship, the dedication of this chapel to these saints is only firmly datable to the mid-sixteenth century. This dedication may have reaffirmed a long-standing tradition for the space, or it may reflect a more recent change in the chapel’s use.

While I concur with those scholars who affirm the Johanniters as the patrons of the Amsterdam Holy Kinship, I think it worthwhile to acknowledge the other possibilities that have been suggested. For example, scholars have opined that the panel was made for the Dominicans in Haarlem. This view rests primarily on the association between the Dominicans and the Confraternity of the Rosary with its strong Marian elements. The Holy Kinship, however, focuses on the family of Christ rather than the veneration of the rosary and does not seem completely apt for that particular devotion. Geertgen, and his atelier, worked for various patrons in Haarlem on an ad hoc basis and completed a rosary-themed panel for the Dominicans.33 That panel was not the Holy Kinship but was the so-called Institution of the Rosary by Saint Dominic (after 1478), which coincided with the establishment of the Confraternity of the Rosary in Haarlem (ca. 1478).34 In addition to the confraternity, the Haarlem Dominicans also appear to have established an association dedicated to “Our Beloved Lady and the Worthy Mother Anna” (ca. 1480).35 It is unclear how successful this particular organization was in comparison to other Anna-centered cults.

Both the Johanniters and the Dominicans had reasons to possess the Amsterdam panel. Another Haarlem group, however, also had in interest in the subject of Anna’s trinubium: the Carmelite order claimed intimate connection with the story of the life of Anna. In the various accounts of the saint’s life circulating in late-medieval Christianity, the monks of Mount Carmel–forerunners to the Carmelites–played a major role in the story of her nativity. Specifically, these narratives credited the monks with being instrumental in brokering the marriage of Anna’s parents, Emerentiana and Stollanus.36 The Carmelites took this story seriously and used it to position themselves among the various advocates of Anna veneration at work in the late medieval and early modern periods. Although various Carmelite churches established active Anna cults, as Maximilian’s presence at the 1496 dedication of the Brotherhood of Anna at the Carmelite church in Worms makes clear, there is no evidence that the Haarlem Carmelites oversaw an Anna confraternity or ordered such an image.

Although other groups in Haarlem were associated with Saint Anne, the prominence afforded Elizabeth and John the Baptist supports the prevailing hypothesis of the Johanniters as the patrons for the Amsterdam panel. This brings me to the second point of departure in the composition, which is more complex than the first and speaks to how the image might have helped the knights manage their current woes. Unlike the 1470 version, or that of 1473, which situates Anna, the Virgin, and Christ at the center of the composition, the Amsterdam rendition shifts these figures to the sides. The space created by this displacement contains an intriguing pairing. A polychromed sculpture of the Sacrifice of Isaac stands atop an altar (fig. 4). Isaac kneels in prayer as he impassively awaits the imminent killing stroke that Abraham readies above him. Directly below the altar, three boys sit engaged in a game of make-believe (fig. 5). Simon, with his falchion, watches as James the Greater pours liquid from a cask into a goblet held by his brother John the Evangelist.37

Like the rest of the children depicted in the image, these boys were to become apostles and martyrs. Their specific vitae may help explain why they, rather than the others, occupy the center of the composition. James and John, the children of Mary Salomas, were known as the Boanerges (Sons of Thunder) for their fiery preaching. James the Greater was the first of the apostles to die and his cult was venerated at Compostela.38 De Voragine’s Golden Legend identified James as being instrumental in the conversion of Spain to Christianity, albeit posthumously and through miracles.39 Between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, Christians associated the saint with being a crusader and defender against the Moors.40 The recently completed reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula (1492) reinforced this image of James. John was the beloved of Christ and author of an eponymous gospel as well as the Apocalypse. According to Christian belief, God intervened to save John from certain death so that the saint could continue to preach. One of the attempts made on the apostle’s life involved his drinking from a poisoned cup.41 Simon, son of Mary Cleophas, was martyred in Persia by means of a falchion.42 According to the Golden Legend, the saint’s name “means obedient, or one who bears sadness.”43 Taken together, the trio puts a great deal of emphasis on preaching, the defense of the faith against infidels, and on obedience–all important traits for the Knights of St. John as members of a crusading order of monks.

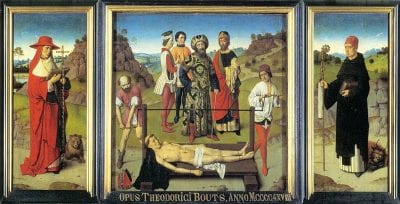

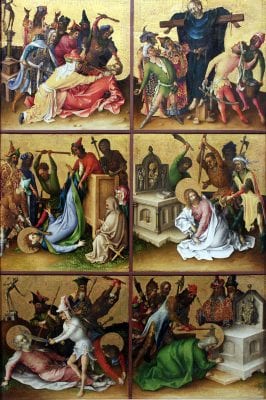

Saints, Suffering, and Stoicism

Rather than appearing as the men mentioned in the Golden Legend, these three saints are depicted as children. In preparation for what awaits them, they busy themselves with the attributes of their future sacrifices. The boys use the implements of their martyrdom as toys and show no sign of apprehension as they engage in a potentially dangerous game of make-believe. They, like the statue of Isaac on the altar, already display the impassivity that was a hallmark of Christian martyrs in works like the Golden Legend.44 Hagiographies recounted the stories of saints who underwent horrific tortures without betraying their religion. As heroes and heroines of the faith, martyrs were required to face bodily destruction without fear or signs of outward pain. Images like Dieric Bouts’s Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus of 1458 (fig. 6) or Stephan Lochner’s Martyrdom of the Apostles Altarpiece of 1435–40 (fig. 7), for example, showed pious viewers how the saints endured such torments with stoicism.45 Rather than wailing in agony, the martyrs meet their deaths with calm, and sometimes even joyous, acceptance of suffering. In the fifteenth century, the faithful could draw upon numerous stories of saints who died happily for their faith. The story of Saint Lawrence was perhaps one of the best known thanks to the martyr’s culinary simile regarding his own condition. After being placed on the gridiron, the saint taunts his tormentors:Laurence said to Valerian [who oversaw his torture]: “Learn wretched man, that your coals are refreshing to me but will be an eternal punishment to you . . . I have confessed Christ, and being roasted I give thanks!” And with a cheerful countenance he said to Decius [the emperor who ordered the torture]: “Look, wretch, you have me well done on one side, turn me over and eat!”46

Not only does the saint willingly accept his death, he jokes about it to demonstrate that his corporeal suffering means nothing to him. The casual manner with which James, John, and Simon play with the implements of their future deaths evokes a similarly humorous response–rather than fearing these objects, the boys turn them into toys. Humor, however, was not the only–or even primary–way that martyrs met their fates. The deaths recounted in hagiographies record feats of extreme stoicism in which the victim turns the tables on the tormentor by bearing each punishment without complaint.

In the Amsterdam Holy Kinship, the figure of Isaac thematizes this form of ideal impassivity. He acts as a typus-Christi who embodies the patience and obedience required of those in religious orders. The degree of his stoicism is made all the more evident when juxtaposed with the narratives in the choir screen behind him (fig. 8). Unlike Adam and Eve who disobey God and give in to sin in the Temptation scene, to the left, Isaac meekly complies with divine will. The failure of the primordial pair in the garden, according to Christian belief, necessitates the sacrifice of Christ, which Isaac’s act prefigures. In the Expulsion scene, to the right, Adam and Eve gesticulate wildly as they flee the angel who brandishes a sword in warning. Their lack of stoicism amplifies their moral and spiritual weakness. Isaac, in contrast, does not flinch as Abraham prepares to administer a mortal blow–a gesture that mimics the raised sword of the angel banishing Adam and Eve–but instead prays quietly as he awaits death. Isaac’s impassivity acts as a marker of his virtuousness and spiritual rectitude. His calm, prayerful response to what awaits him, and his willingness to die if it is God’s will, echoes outward (and forward through time) as it amplifies the monastic and crusader virtues of the trio assembled below him. Although not yet as stoic as Isaac, the three boys in the Amsterdam Holy Kinship approach the instruments of their bodily torment in a joyous manner that contrasts with the horror that Adam and Eve display in the face of the punishment they have earned. Rather than being a sign of childishness, like the book-defacing boy depicted in Massy’s 1507–8 version (see fig. 2), the playful attitude of John, James, and Simon (fig. 5) allows them to face their future deaths as calmly as Isaac because they have faith and hope in God’s mercy and in the eternal salvation that rewards their sacrifices.

The game of simulated martyrdom that the three young saints play prepares them for what awaits them as adults. In other words, their activity is not idle but, instead, is a form of “serious play,” to borrow Huizinga’s formulation. The pairing of Isaac and the three saints, located at the center of the image, constitutes a visual gloss on the virtues expected of monks like the Johanniters. As such Isaac and the saints act as exemplars for the viewer; John, James, and Simon mediate their exemplarity through the lens of virtuous play. Their activity, in theory, extends an invitation for the viewer to join them and learn obedience, sacrifice, and patience. For the Haarlem Knights of St. John, the virtues that James, John, and Simon embody may have helped the Johanniters deal with their travails in a patient and virtuous manner. Like the saints, and Isaac, the knights could also place their faith and hope in God’s divine justice and mercy. The presence of the knights’ patron saint in the foreground, pointing to Christ as the Messiah, made evident in whom they should put their faith as they endured life’s trials and tribulations. This raises an important question: how could playing at virtue make one virtuous? The answer, in part, depended on how one played.

Virtuous Games: The Concept of Eutrapelia

Games and play, in all their forms, were ubiquitous, even in monasteries.47 Monks were expected to live austere lives away from the world, but this did not preclude them from experiencing joy, especially if it was instrumental in bringing them closer to God.48 For some churchmen, like Bernard of Clairvaux and Francis of Assisi, those in religious orders were God’s fools whose choice not to abide by the norms of secular life constituted a sacred game.49 Churchmen divided play into two sorts–licit and illicit–and discouraged playing games that involved chance or gambling as a waste of time and as the work of the devil. The suspicion regarding pastimes had a long history in the Church dating to at least Augustine if not earlier. Augustine expressed contempt for public games and the theater His objections, noted, for example, in his Confessions and the City of God, are strongly Platonic in nature in that he sees games and the theater as deceitful and as threats to the mind and soul.50 As such, they are deleterious to the commonwealth and disastrous for the faithful. Further, he sees Roman-style gladiatorial games and Greek-inspired tragedies and comedies as being particularly harmful because they do not elevate the mind but, instead, draw the soul to pagan ideas that put the spectator in the thrall of evil. As monks living under the rule of Augustine, the Haarlem knights were likely aware of the concerns surrounding various forms of amusement. They possessed many of Augustine’s writings in their library, including the City of God and Confessions, and were probably cognizant of his cautions against such problematic activities.51

Augustine, however, was not the sole authority on leisure, and by the fifteenth century the Church’s views on games and pastimes had evolved to allow for licit forms of entertainment. Approved games were those that lifted up the spirit, eased the mind, and led one to virtue rather than vice. Images of the Christ Child playing with bells, flowers, or balls gave the faithful ample evidence of the existence of licit pastimes. In the north, the custom of carrying dolls of the Christ Child to church during Nativity celebrations offered the entire community a chance to engage in sacred play.52 As the priest sang and rang sacred bells, the congregation would rock and sing to the dolls they had brought with them.

For play to be effective and meaningful in a religious context, it had to be directed toward elevating the mind and the spirit. Within these parameters, even diversions usually considered suspect could be worthwhile if they were in the service of a noble goal. A good example of this is Ingold of Basel’s Little Book of Golden Play (ca. 1432). In his moralizing tract, the author provides a list of pastimes designed to make the player a better person. Although some of the games could be detrimental if played incorrectly (i.e., for the wrong reasons), Ingold recommends:chess versus pride, board games against gluttony, card games versus promiscuity, dice games against parsimony, shooting versus fury, dancing against sloth and, finally, playing stringed instruments versus envy and hate.53

For proponents of these sorts of pastimes, morally beneficial games fell under the category of eutrapelia, or play that inculcates virtue.54 Viewed though this lens, the game of make-believe the boys play in the center of the Amsterdam Holy Kinship could be termed eutrapelic as it focuses on edifying concepts such as obedience to God’s will and hope in his mercy.

The Haarlem Johanniters were likely familiar with the concept of eutrapelia as their library included works by Aristotle and Boethius, as well as Aquinas’s Summa Theologica and de Voragine’s Golden Legend, each of which contains references to virtuous play. Aristotle discusses the concept of eutrapelia in the Nicomachean Ethics. The sixth-century philosopher Boethius transmitted the Aristotelian idea to Europe in his work titled On the Hebdomads. Thomas Aquinas revived the idea for late medieval and early modern Christians in his Exposition of the “On the Hebdomads” of Boethius.55 In his explanation of Boethius’s short theological pronouncements, Aquinas provides a robust defense of play, as long as it is directed toward the apprehension of wisdom. For the learned Dominican, this type of play is a process that begins with drawing inward to the “house” of the soul. He states that, “one must consider that the contemplation of Wisdom is suitably compared to play . . . because play is delightful and the contemplation of Wisdom possesses maximum delight.”56 Aquinas’s observations on the subject of eutrapelia were not limited to his explanations of Boethius. In his magnum opus, the Summa Theologica, the author offers his thoughts on the matter and acknowledges Aristotle’s approbation of the term eutrapelia.57 Recreation, Aquinas notes, could be useful and licit as long as it was employed with moderation and did not interfere with the completion of one’s primary tasks.58 Such relaxation, however, should not be undisciplined. Aquinas (quoting Tully) argues that for rest and diversion to be acceptable, they must be regimented.Tully says that, “just as we do not allow children to enjoy absolute freedom in their games, but only that which is consistent with good behavior, so our very fun should reflect something of an upright mind.” . . .we must be careful, as in all other human actions, to conform ourselves to persons, time, and place, and take due account of other circumstances, so that our fun “befit the hour and the man,” as Tully says (De Offic. i, 29).59

Further, Aquinas notes that licit relaxation was especially necessary for those occupied in contemplation, which could weary the soul.60 He underscores his assertion by noting that certain forms of leisure have apostolic roots. Aquinas relates the story of John the Evangelist, who scandalized onlookers by relaxing with his disciples. The saint explained his actions by drawing a metaphor between the mind and a bow kept in tension too long. Just as a bow will eventually crack if it is never relaxed, the mind will also break if it is denied release. This same anecdote also appears in the Golden Legend. In de Voragine’s version, the Evangelist explains, “we would have less strength for contemplation if we never relaxed . . . the human spirit, after it rests a while . . . is refreshed and returns more ardently to heavenly thoughts.”61 John was not the only saint credited with using the metaphor of the bow to justify holy play. De Voragine also records an event in the life of Saint Anthony Abbot that closely mirrors the Evangelist’s story. Like the Evangelist, Anthony acknowledged the necessity of revitalizing the mind and soul in the course of doing God’s work. Both examples, the Evangelist and Anthony, were readily accessible to fifteenth-century Christians and provided justification for licit pastimes.

When placed in this larger context, the young Evangelist’s membership in the trio of boys at the center of the Holy Kinship would seem to support reading their activities as being the type of recreation needed to refresh the mind for heavenly pursuits. They play at make-believe in a well-behaved manner that, following Aquinas, appears to be moderate, disciplined, and reflective of the uprightness of their minds. Their activity provides an engrossing diversion that offers a moment of rest and refreshment for saints and future martyrs whose lives were dedicated to God’s plan of salvation. For the Knights of St. John, who were also dedicated to the Church’s mission of redemption, the need to find respite from daily concerns was more than just an abstract, theoretical concept.

At the heart of the commandery’s grounds was a large, gated orchard, which was a contemplative place of rest from their cares, where the brothers could take walks and find solace.62 The Amsterdam panel may make explicit reference to this space in the landscape just visible through an open doorway in the side aisle on the left. The trees and meadow depicted screen off the view of the outside world, leaving only a glimpse of a step-gabled building (perhaps the hospice?). Like the architecture of the church, this view is not an exact portrait of the orchard but an evocation of a place known to the monks. The pairing of the contemplative relaxation available in the orchard with the meditative acts occurring in the panel’s foreground further inflects the activity in which the boys at the image’s center are engaged. It also makes clear that the orchard was not the only outlet the Johanniters had for devotional activities that provided rest and refreshment for their souls and minds. The commandery contained many devotional images (like the Holy Kinship itself) that provided the knights with ample opportunity to “relax the bow.”

The Amsterdam Holy Kinship is a complex image that supports multiple readings. The various threads woven throughout it–Eucharistic, Christological, Marian, and hagiographical–provided the knights with multiple routes of inquiry capable of sustaining prolonged meditation. The need for such contemplation is enacted in the image itself, which shows pious men and women absorbed in thought or quiet conversation after the completion of the Mass (signaled by the extinguishing of the candles on the rood screen). Each of the saints depicted in the image had the potential to lead the Johanniters to a greater understanding of their faith. Contemplating the image, and assembling the various mnemonic and devotional catenae it facilitated, constituted a sacred game in which the monks could engage whenever they wished. In theory, playing such a game could lead a pious viewer to ruminate on Christian doctrine by working through the multiple meditational routes available in the image. For Aquinas, such contemplation resulted in “maximum delight” because it was in the pursuit of divine wisdom.

Though not the largest figures in the panel, the boys at the heart of the composition concretize the pursuit of virtue that the contemplation of the image encourages. Their own observance, and adoption, of Isaac’s example becomes a model for the devout viewer and offers a paradigm for dealing with travail. In the context of the holy game of make-believe they play, their impassivity and obedience are the outward signs of their internal virtues and their belief in the eternal salvation offered to those faithful to the Church. For the Knights of St. John, these moral characteristics were the same as those required of monks and were worthy of adoption in daily life. The three playing saints in the Holy Kinship established that adversity–like the troubles the monks had endured in the past–should be embraced in the service of furthering God’s glory. They also demonstrated that engaging in the sacred play appropriate to those dedicated to holy pursuits could give the Johanniters more strength for, and from, contemplation.

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are mine and I alone bear responsibility for any errors.