One of the most intriguing commissions of a painting by Rembrandt came from Antonio Ruffo in 1653 (now in New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art). This article analyzes the contradictory identifications of the subject of this work, from the very moment it arrived in Messina. With a novel focus on three layers of intrinsic and contextual information that are fundamental to identify the figure, it concludes that Rembrandt did not depict Aristotle or Albertus Magnus or any other historical figure, but instead the universal philosopher.

“To me this is one of the monuments of Western culture. We have Aristotle as a philosopher with a central, moral problem of human experience. We see Aristotle in his late years and he is thinking, will I be remembered like I remember Homer? Material things, honor, fame, so what? Did I say anything important?”1

With this poetic statement, made in 2013, Walter Liedtke professed his reverence for the painting by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669). Indeed, the work, made in 1653, is not a customary depiction of a classical philosopher (fig. 1). Rembrandt made use of “modern-day” dress and added particular attributes, highly unusual both in the Netherlands—where it was created—and also in Spanish Sicily, where it was commissioned. In fact, the portrait is so curious that it casts into doubt the very identification of the subject as Aristotle. This uncertainty is further exacerbated by the fact that even the commissioner of the portrait was uncertain about who was ultimately represented in the painting.

In this article, I will analyze the Sicilian commission of Rembrandt’s painting and the various identifications of the figure that have been made, from the earliest sources into the present. A new question that presents itself is how the perception of the figure in Messina can be equated with the perception of classical philosophers in Amsterdam, and on what level the latter is applicable to Rembrandt’s choice of subject. In that respect, Rembrandt would have been informed by Spanish artists’—in particular Ribera’s—handling of classical philosophers, which was so fundamentally different from the standards in the Netherlands. With a new focus on three layers of information that are crucial to the identification of the subject (Ruffo’s autonomous request for a figure in 1653; the link between Rembrandt’s three paintings for Ruffo; and the context of Ruffo’s series of seven paintings), my conclusion is that Rembrandt depicted not Aristotle in particular, as has generally been stated, but rather the universal image of the philosopher.

Ruffo’s Commission

Very soon after Rembrandt’s painting arrived at its destination in 1654, it was described as a half-length figure of a philosopher made in Amsterdam by the painter Rembrandt, probably representing Aristotle or Albertus Magnus.2The owner was Antonio Ruffo (1610/11–1678), a wealthy aristocrat who owned a palace in the city of Messina on the island of Sicily, then under Spanish rule. He collected paintings from various artists from all over Europe; his inventory lists works by Titian, Ribera, Poussin, Dürer, and Rubens.3

The note referenced above gives a rare and crucial insight into how Rembrandt’s painting was perceived at the time. Unfortunately, the only documents to this effect that remain are from Ruffo’s milieu, so we can only wonder as to Rembrandt’s intentions. Some of the information in this 1654 note triggers specific questions: first, did Ruffo request a half-length figure of any type, or did he expressly ask for a philosopher?4 And second, more importantly, why did conspicuous confusion about the identification given in Ruffo’s inventories persist for more than a century (see Table 1)?5 Saying that the figure could be Aristotle or Albertus Magnus is like saying he could be Galileo Galilei or Stephen Hawking. In other words: Ruffo had no clue. So what happened here?

| Table 1 Overview of the different identifications of the figure in Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (here identified as The Philosopher) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Name | Identification | |||

| 1654 | Van Goor | Painting | |||

| 1654 | Inventory Ruffo | Philosopher: Aristotle or Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1657 | Note Ruffo | Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1660 | Letter Guercino | Half-length figure | |||

| 1660 | Letter Guercino | Physiognomist | |||

| 1661 | Letter Preti | Half-length figure | |||

| 1662 | Letter Van Hol | Aristotle | |||

| 1668-77 | Inventory Ruffo | Albertus Magnus or Aristotle | |||

| 1668-77 | Inventory Ruffo | Aristotle or Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1670 | Letter Brueghel | Half-length figure | |||

| 1671 | Brandi | Painting | |||

| 1678 | Inventory Ruffo | Aristotle | |||

| 1689 | Inventory Ruffo | Aristotle | |||

| 1710 | Inventory Ruffo | Aristotle or Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1783 | Inventory Ruffo | Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1810 | Auction Christie’s | Sculptor | |||

| 1815 | Catalogue London | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1824 | Nicol | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1836 | Smith | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1838/54 | Waagen | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1877 | Vosmaer | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1883 | Von Bode | Portrait of a Man | |||

| 1885 | Dutuit | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1893 | Catalogue London | Pieter Cornelisz Hooft | |||

| 1894 | Michel | Portrait of a Man | |||

| 1895 | Bredius and Hofstede de Groot | Portrait of a Man | |||

| 1897 | Six | Torquato Tasso | |||

| 1897-1906 | Von Bode | A Bearded Man | |||

| 1900 | Von Bode | Portrait of a Scholar | |||

| 1900 | Glück | A Dutch Poet or Scholar | |||

| 1903 | Marguillier | A Poet or Scholar | |||

| 1904 | Rosenberg | A Portrait of a Scholar | |||

| 1905 | Neumann | A Man | |||

| 1906 | Rosenberg | A Portrait of a Man of Letters / Savant | |||

| 1907 | Von Bode | Portrait of a Savant | |||

| 1908 | Grant | Philosopher or a Student | |||

| 1909 | Valentiner | The Savant / Virgil | |||

| 1909 | Kruse | Torquato Tasso | |||

| 1910 | Waldmann | Virgil | |||

| 1914 | Ruffo | Aristotle or Albertus Magnus | |||

| 1915 | Schmidt Degener | A Poet / Virgil / Tasso | |||

| 1916 | Hofstede de Groot | A Bearded Man | |||

| 1917 | Hoogewerff | Aristotle | |||

| 1918 | Ricci | Aristotle | |||

| 1919 | Ruffo | Aristotle | |||

| 1923 | Meldrum | Portrait of a Man of Letters | |||

| 1924 | Neumann | Aristotle | |||

| 1925 | Backer | Aristotle | |||

| 1928 | Exhibition London | A Savant | |||

| 1929 | Washburn Freund | Aristotle | |||

| 1930 | Exhibition Detroit | Aristotle | |||

| 1935 | Bredius | Aristotle | |||

| 1947 | Mahon | Aristotle | |||

| 1953 | Slive | Aristotle | |||

| 1956 | Benesch | Aristotle | |||

| 1957 | Saxl | Aristotle | |||

| 1962 | Rousseau | Aristotle | |||

| 1968 | Emmens | Aristotle | |||

| 1969 | Bredius | Aristotle | |||

| 1969 | Gerson | Aristotle | |||

| 1969 | Held | Aristotle | |||

| 1976 | Valentiner | Aristotle | |||

| 1984 | Deutsch Carroll | Aristotle | |||

| 1984 | Schwartz | Aristotle | |||

| 1986 | Tümpel | Aristotle | |||

| 1995 | Giltaij | Aristotle | |||

| 1995 | Von Sonnenburg, et al. | Aristotle | |||

| 1997 | Giltaij | Aristotle | |||

| 2002 | Golahny | Aristotle | |||

| 2003 | De Gennaro | Aristotle | |||

| 2004 | Liedtke | Aristotle | |||

| 2005 | Giltaij | Aristotle | |||

| 2005 | Van de Wetering | Aristotle | |||

| 2006 | Crenshaw | Aristotle or Apelles | |||

| 2006 | Moormann | Aristotle | |||

| 2006 | De Winkel | Aristotle | |||

| 2007 | Liedtke | Aristotle | |||

| 2014 | Bikker | Aristotle | |||

| 2016 | Sheers Seidenstein | Aristotle | |||

We can assume that Ruffo had not asked for a specific philosopher, or he would not have had to guess. Considering other commissions made by the patron, it was more or less his practice to be non-specific. But if Rembrandt were only asked for a half-length figure, then looking at his oeuvre, with its many biblical figures, wouldn’t it be more reasonable to suspect an apostle or a saint? There is only one other philosopher known by Rembrandt, which is mentioned in a collection in The Hague in 1752. This piece, which is overlooked in the literature, is called a life-sized three-quarter-length figure (kniestuk), a description that would have been suitable for the painting in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection as well.6 Most likely this was a type of general philosopher similar to the one ordered by Ruffo. It makes sense that Ruffo would have commissioned a philosopher by giving hints as to his wishes to the two mediators of this transaction, Giacomo di Battista in Messina and Cornelis Gijsbertz van Goor in Amsterdam.7 But Rembrandt clearly made it difficult to identify the picture.

The current title of the painting, Aristotle with the Bust of Homer, raises some questions with regard to Ruffo’s understanding of the painting. It is hard to believe that this classical bust originally would have been mistaken as anything but the image of the famous poet. After all, the particularities of a blind man with a headband as identifying Homer could be seen even in seventeenth-century illustrated encyclopedias.8 However, evidence that the bust was not recognized as Homer lies again in the confusion regarding the identification.9 The classical Greek Aristotle and the thirteenth-century Albertus Magnus—who studied and worked in Cologne, Paris, Padua, and Bologna among other cities—shared a common interest: the natural sciences.10 Therefore, the two figures do share a connecting thread and if the bust had been clearly recognized by Ruffo as the image of Homer, then there would have been no logical reason to match it with Albertus Magnus.11 Aristotle shares a more obvious connection to Homer, although he certainly has no exclusive rights to a relationship with the poet.12

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the question as to whether the portrait featured Aristotle or Albertus Magnus seems to have been forgotten. Leaving aside the classical bust, various writers have found the leading clues to the philosopher’s identity in the figure’s clothing, which is a mixture of “classical” white drapery, an invented black sleeveless tunic, and a sixteenth-century hat of the sort that was also worn by seventeenth-century scholars.13 This combination resulted in alternative identifications of the figure as Virgil, Torquato Tasso, or, a figure even closer to Rembrandt’s own time, Pieter Cornelisz Hooft (see Table 1). Some authors did not wish to burn their hands on a false identification and titled the work merely as a “savant” or a portrait of a scholar or a bearded man (of letters). From 1929 on, however, only one of the two original identifications continued to be associated with the picture. Since then, Rembrandt’s figure has been consistently identified as Aristotle. To see if this is justified, let us take a closer look at the image of this philosopher.

The Image of Aristotle

Contrary to what might be expected, Aristotle—despite being one of the most famous philosophers—is quite absent from seventeenth-century painting. This is particularly noteworthy in the Netherlands, where anecdotes about classical thinkers were (literally) popular. Owing to the rise of easily accessible commonplace and emblem books in the vernacular, nonacademic readers were able to read (and view) stories of Alexander the Great visiting Diogenes or of Hippocrates diagnosing Democritus. Joost van den Vondel’s Gulden Winckel (Amsterdam, 1613), for example, includes many philosophical praatjes bij plaatjes (conversation pictures). Plato and Socrates play a small role in his book, but Aristotle never once appears.14

So how did the seventeenth-century art lover recognize the philosophorum princeps? A strong possibility is through illustrated encyclopedic overviews. In André Thevet’s Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres (1584), Aristotle is depicted en profil with long curly hair, a long beard, a hat, and a cape (fig. 2).15 This type—with or without an elevated hand—was characteristic for both the Middle Ages and the early modern period and was also circulated in separate prints by engravers such as Enea Vico (1523–1567) (fig. 3). Another type of depiction was as a beardless youth derived from an en profil relief, which is known from a print in Fulvio Orsini’s Imagines et elogia vivorum illustrium (Rome, 1570).16 Thirdly, as can be seen in a drawing by Theodoor Galle (made after a bust), Aristotle is shown with short hair and a short beard.17 Another bust look-alike was included in Joachim von Sandrart’s famous compilation of 1675–80, Academia todesca delia architectura, scultura e pittura: in a set of six medallions, Aristotle is depicted with a long beard, loose locks of hair, and a linen head cover (fig. 4). In frontispieces we find a fifth variant, with Aristotle as a bald-headed graybeard (fig. 5). Given this broad spectrum, it would have been relatively important to add Aristotle’s name to a title or description of a work to identify him.

From natural history to astronomy, from rhetoric to poetics, the reception of Aristotle was shaped by many disciplines, but the tendency to question the authority of the philosopher was made especially urgent by new scientific approaches and experiments. Borelli was in conflict with Aristotle as a result of his research on the movements of animals; Swammerdam disagreed with the Aristotelian notion of spontaneous generation by insects; Descartes’s mechanistic worldview was an explicit replacement of the older Aristotelian paradigm; and Galileo came to alternative conclusions in the lively debate on gravity. The latter was perfectly visualized in the frontispiece of a publication in 1641, with Galileo’s opponents Aristotle and Ptolemy representing the old and his fellow thinker Copernicus the new (see fig. 5).18

In the humanities, Aristotle’s ideas caused less conflict. Aristotle’s Poetica continued to play a role, as evidenced in publications by Gerardus Vossius and Daniel Heinsius. Vondel, among others, was inspired by strict Aristotelean rules in theater plays.19 Aristotle was also visible in Diogenes Laertius’s frequently published and translated biography of the classical philosophers. Aristotle’s moralist sayings, as derived from these works, were in return used for comptoiralmanakken.20 These wise epithets were common even in the decorative arts.21 Therefore, despite a lack of (consistent) depictions of the ancient philosopher in art, and his controversial role in science, it can be assumed that Aristotle was not completely absent from the minds of the people of Amsterdam—Rembrandt included. The artist owned a bust of Aristotle and must have known about the philosopher even as a schoolboy in Leiden.22 But did this familiarity lead to the philosopher’s depiction?

Rembrandt’s Choice

As argued above, it is logical to assume that Ruffo specifically requested that Rembrandt paint a philosopher (and not just a half-length figure).23 The result, however, was not a response to popular philosophical themes in the Netherlands at the time. Only a year prior, Caesar van Everdingen had depicted the popular story of Diogenes and Alexander the Great at a market.24 In his own early years Rembrandt was inspired by the Caravaggesque movement in Utrecht and was therefore aware of the frequently depicted pendants of the laughing Democritus and crying Heraclitus, as well as the more stoic image of the dying Seneca. His own teacher, Pieter Lastman, depicted Hippocrates visiting Democritus in 1622.25 But Rembrandt chose none of these for the subject of his painting.

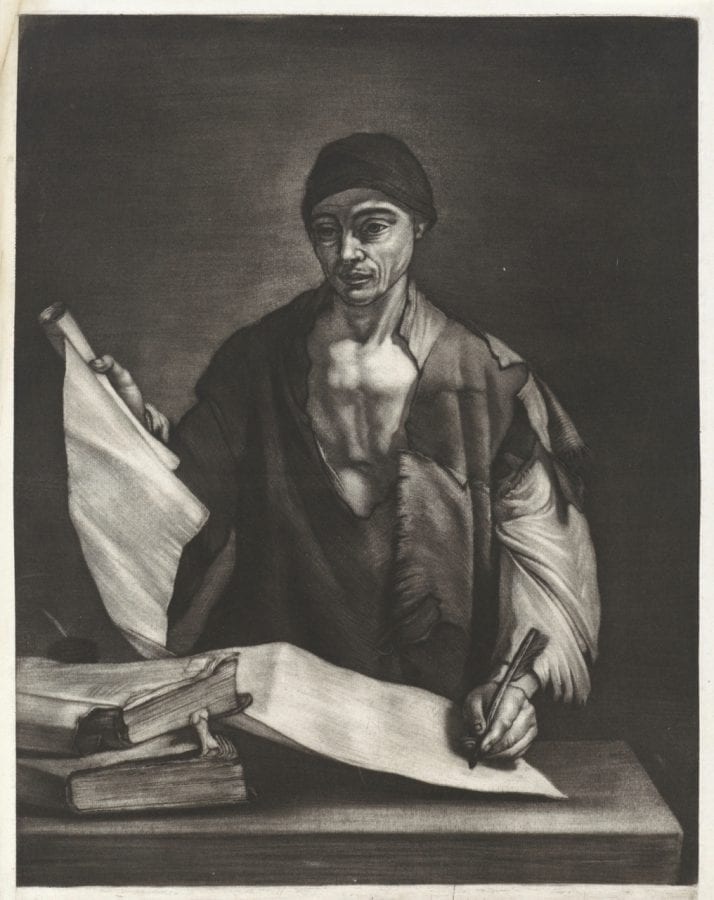

Instead, Rembrandt must have investigated or been in some way aware of the Spanish approach to representing philosophers. One particular artist is noteworthy here: Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652). His work, an example of which Ruffo bought in 1647, was also to be found in Amsterdam collections from 1639 onward: Gysbert van Goor (son of Rembrandt’s agent Cornelis Gijsbertz van Goor) and Rembrandt’s relative by marriage, Gerrit Uylenburgh, owned paintings by Ribera; the latter even owned a painting of a philosopher.26 Ribera, known in the North as Spanjolet, was famous for a series of philosophers that were put into print by Bernard Vaillant. Vaillant made, for example, a reversed mezzotint of a philosopher that was once entitled Aristotle—defining the precise subject is difficult in many of these unspecified images of classical thinkers (fig. 6).27 This series was produced in 1672 and could therefore not have been seen by Rembrandt. He did, however, own a boeck with (reproductions of) Ribera’s etchings.28 We do not know if this “book”—likely a bound compilation of prints—contained philosophers, but the well-known Southern formula of a life-sized isolated man in a dark room, standing at a table with books, papers, pens, or specific scientific tools, appears to be more of a prototype for Rembrandt’s figure than the Northern tradition of depicting the philosopher in an active interaction with other people, often situated outdoors.

Yet Ribera’s type was not entirely sufficient as a model for Rembrandt’s philosopher. Rembrandt ignored the beggars’ tatters typically worn by the Spanish artist’s subjects. Instead, he chose to depict the figure in a rich black and white dress, which Ruffo associated with guisa di monaco (the dress of a monk), in particular that of the Dominican order, which was the religious background of Albertus Magnus.29 Apparel consisting of white “classical” drapery, a black sleeveless tunic, a golden chain, and a hat was often used by Rembrandt and his students for unidentified scholars, but none of these attributes have anything to do with Aristotle or any other classical figure in particular. The facial characteristics are likely taken from a model and not, by contrast, from the bust of the philosopher owned by Rembrandt or other extant visual sources on Aristotle, since they have little in common with those discussed previously.30 The only telling, but small, reference to Aristotle might be the ring in his ear and the one on his finger, since this jewelry is described in textual sources, but it should be noted that Rembrandt gave such accessories to a few generic images of scholars as well.31

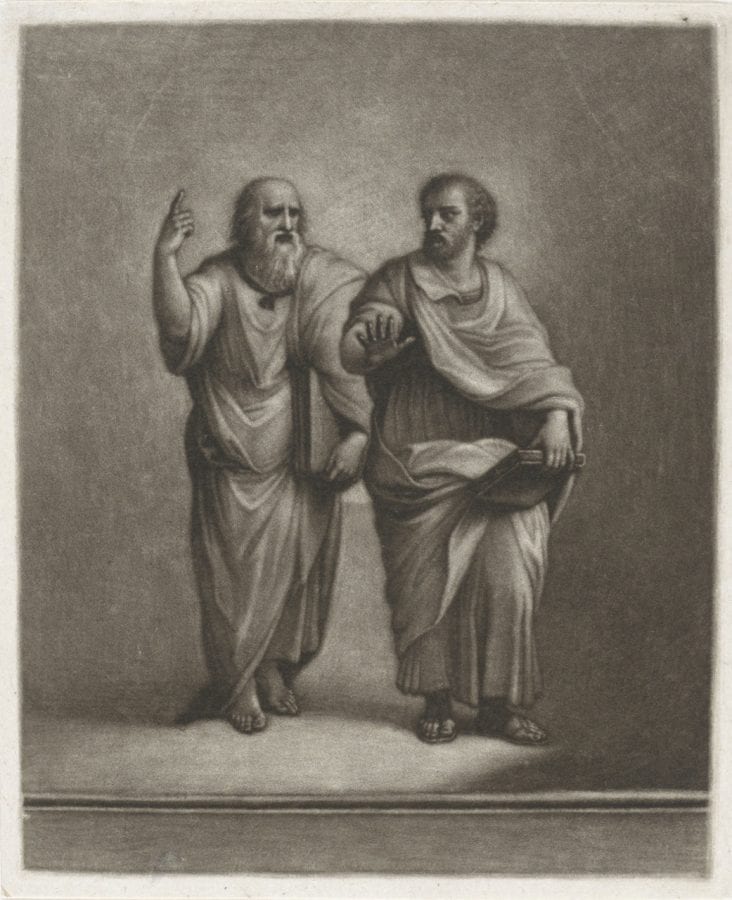

Attention must also be paid to the philosopher’s arm, which is not elevated as is typical of Aristotle (see fig. 2).32 This gesture is represented most famously in Raphael’s School of Athens (1509–11, Vatican), where Aristotle is shown in complement to his teacher Plato, both referring with their gestures to their own opposing philosophies of the ideal and the visible world (fig. 7). I argue, however, that Rembrandt gives his figure, with the hand resting on the sculpted head (and therefore the mind), a different pose altogether. This gesture can instead be ascribed to the ultimate image of thinking: the central activity of the philosopher.

Conclusion

In later years Ruffo sought pendants for Rembrandt’s figure and asked the seventy-year-old painter Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino, to comply. In 1660 Guercino wrote to the nobleman that he would be honored to make a cosmographer to accompany Rembrandt’s “physiognomist.” Guercino based this surprising identification on a sketch made of the painting. Ruffo had said nothing more about Rembrandt’s choice than to specify its size, and that Guercino’s painting had to be a half-length figure.33The description of the figure without any further reference to the content or identification can also be seen in a letter from 1661 by the artist Mattia Preti, following Ruffo’s request for another work to accompany Rembrandt’s painting, and again in a letter of complaint by Abraham Breughel to Ruffo in 1670 (Table 1).34 They both mention only a half-length figure when referring to Rembrandt’s painting. Thus it can be assumed that the content of the pendants was not Ruffo’s primary concern: first and foremost they had to look good in line with one another and preferably be symmetrical when displayed together in his palace.35

Ruffo continued to collect by commission for this particular series, most probably with the same request: a half-length figure being more or less specified. In 1661 Rembrandt made an Alexander the Great, Mattia Preti finished a Dionysius of Syracuse in 1662, and Rembrandt’s Homer arrived another year later. The desire to identify the philosopher in the work under discussion has often been connected with finding an intrinsic link with Rembrandt’s latter two figures. However, the 1653 philosopher needs first and foremost to be understood as an autonomous painting: only eight to ten years later did Rembrandt create the other two.36 From Ruffo’s perspective this addition was to complement his series of half-figures executed by the great masters of his time. From Rembrandt’s perspective he was only aware of the paintings that he himself had made for the collection. So in a way, it is justified to retrospectively search for a link among the three. Indeed, Alexander and Homer can be combined with Aristotle, as was done by the shipmaster Nicolaes van Hol in an addition to the receipt for the latter two works in 1662 (see Table 1).37 However, this combination is only known in textual sources such as Plutarch.38 The combination of the three is simply absent in art.

More important and neglected over time is the evidence that Ruffo continued to question the identity of the philosopher (see Table 1) and ignored a unique link with the other two paintings as well.39 He proceeded to expand the series with an Archita Tarantino done by Salvator Rosa in 1668 and finally a painting sent by Giacinto Brandi in 1670, which was defined as the philosopher or as Saint Jerome—another proof that Ruffo struggled, or didn’t particularly care, to expressly define the subject matter. Considering the broad range of this series, it is hard to believe that Ruffo’s commissions were content driven, and Rembrandt’s three paintings therefore should not be seen with a privileged meaning. In short, there are three layers of information that can be considered in an effort to define Rembrandt’s philosopher: Ruffo’s autonomous request for a painting made in 1653; the link between Rembrandt’s three paintings; and the context of Ruffo’s series of seven paintings. Trying to find evidence for the identification of Aristotle, as scholars have done from the early twentieth century until now, means a focus only on step two and neglects several key aspects. This ignores the idiosyncrasies of the figure of the philosopher, its iconographic elements, and the place of the commission in the context of all the paintings displayed in Ruffo’s palace.

Finally, to return to what is actually depicted by Rembrandt, neither the identification of the bust nor the figure on the medal attached to the philosopher’s chain appears to play a specific role in documents from Ruffo’s time.40 Yet Rembrandt incorporated these classical attributes on purpose. Without these elements the figure is merely a seventeenth-century scholar or—if one prefers—a Dominican scientist like Albertus Magnus.41 At the same time, however, these elements are not sufficient evidence to lead to an exclusive association with a specific philosopher from the classical period, such as Aristotle. The result, as depicted by Rembrandt, provides instead the universal image of the philosopher.

The intricate manner of depiction, and the space it leaves for such a case of mistaken identity, compels me to fully identify with Walter Liedtke, who described the painting as follows: “There is more packed into the meaning than usual in a Rembrandt, but I am drawn to it initially because it is compelling. I sort of got it in my gut or my heart.”42