Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ (ca. 1480, Alte Pinakothek, Munich) has one of the most complex narrative structures found in painting from the fifteenth century. It is also one of the earliest panoramic landscape paintings in existence. This Simultanbild has perplexed art historians for many years. The key to understanding Memling’s narrative structure is a consideration of the audience that experienced the painting four different times over the course of a year while participating in the major Church festivals. The goal of Memling’s painting, like that of the liturgical drama which took place in the same setting, was to encourage the revelation that Jesus is the Savior of the participating audience. I propose that it was the panoramic setting that carried this message from the painting to the immediate viewing context. Finally, I suggest that the ultimate goal of Memling’s complex narrative discourse was to help a viewer to experience and reexperience the revelation of Christ.

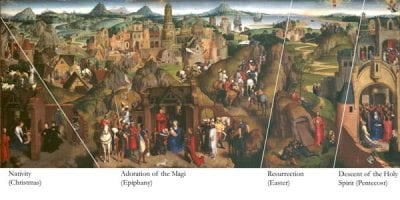

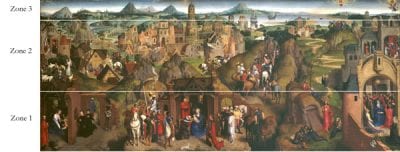

Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ, ca. 1480 (fig. 1), has long been an enigma to art historians because of its complex narrative structure. The large painting, measuring approximately three feet high and six feet wide, simultaneously displays twenty-five events from the life of Jesus and Mary. This type of image, a Simultanbild, is a genre unto itself: an image in which scenes that follow one another in a narrative are put together in the same space where a viewer can see all of the events at the same time.1 Memling painted one other Simultanbild, his Scenes from the Passion of Christ, ca. 1470 (fig. 2), and its narrative follows a clear and regular pattern. The narrative in The Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ, however, is far less easy to follow–its many vignettes seemingly arranged in a random and asymmetrical manner.2

But Memling’s arrangement only appears to be overwhelming and difficult to comprehend. This is because, I will argue, the artist did not intend for a viewer to assimilate the entire painting at one time. Rather he created a convoluted narrative scheme that could communicate with a viewer four different times a year and engage with the liturgy of the four major Church festivals: Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, and Pentecost, each signaled by the four events pictured in the foreground of Memling’s composition. Furthermore, a journey through the vignettes of Memling’s Simultanbild places the viewer within the drama, enabling him or her to feel that the events are happening hic et nunc (here and now), an experience from which comes a revelation of Christ as Savior of the world.3 Memling’s narrative structure is far from being random and irregular, and it works together with the liturgical references and the splendid landscape to bring the lessons from the biblical past into the time and space of the viewing audience, creating a link between the lives of the viewers and the history of salvation, within the context of the liturgical rites taking place there.

The Patron and the Setting

The tanner Pieter Bultinc, alderman of the city of Bruges, commissioned the Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ in 1480.4 He kneels in prayer at the lower left, with his son Adriaan behind him and his coat of arms nearby, and peeks through a window at the Nativity; his wife, Katelyn van Rybecke, kneels near the scene of Pentecost at the right side of the painting. An inscription on a lost frame identified both donors and provided more information about the painting:

In the year 1480 this painting was donated to the tanners’ guild by sir Pieter Bultinc, son of Josse, tanner and merchant, and by the lady Katelyne, his wife, daughter of Godevaert van Rybecke; the chaplain of the guild must after each mass recite the Miserere and De profundis [masses for the dead] for all souls.5

Bultinc’s donation would have hung in the tanners’ chapel, which was near the high altar in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk in Bruges, and been visible from the nave;6 the tanners’ chapel was also the easternmost chapel, which might help explain Memling’s emphasis on the Star of the East.7

The masses for the dead associated with the painting suggest that it had a memorial function, and one can view this work of art as a painted epitaph.8 As was typical for a memorial image such as this, Memling broke down the boundaries between heaven and earth, especially in the tiny scenes of the Ascension and the Assumption, where Jesus and Mary are lifted up to the heavens. Also characteristic of a memorial image is the focus on spiritual intimacy, seen here in the placement of the patron, who is privy to an intimate view of the sweet scene of the Nativity.9 In fact, Bultinc seems to have arrived before the shepherds and thus appears to be the first to experience the revelation of Christ. We can imagine that Bultinc has just witnessed the care with which Mary placed the infant Jesus upon her blue mantle. He can look into the face of Mary and see her expression of awe; he can mimic the angel’s gestures of prayer and reverence, and thus demonstrate his own piousness. To appear in such close proximity to a scene of the Nativity is the prerogative and privilege of the patron and his family; this is what money could buy.10 A painting such as Memling’s demonstrates the patron’s piety and casts him as a model for devotion. He is the viewer’s guide, and he knows what to do. Viewers can follow in his footsteps as he walks within the landscape among the holy figures; he can lead viewers through the narrative so that they can become participants in the events that connect to the liturgy and receive the message of revelation as well.

Disentangling Memling’s Narrative

The involved narrative in Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ has invited several different scholarly interpretations, although there are surprisingly few articles dedicated to this impressive work of art. Ehrenfried Kluckert declared that the main theme of the Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ derives from the vignettes with the stories of the Virgin that bracket the other themes and establish their context, placing the message of salvation in Marian terms and emphasizing her vital role in the redemption of human souls.11 Norbert Schneider applied a “historic-exegetic” analysis to propose that the main motif of the painting is forgiveness and absolution from sin, a complex reading that relies upon a tiny detail, the image of the Ascension, which he misidentified as Christ the Judge.12 Recent literature on fifteenth-century Netherlandish pictorial narrative provides further insight into Memling’s narrative devices.13 Lew Andrews investigated the paradoxical increase of polyscenic narratives in the fifteenth century in the context of artists’ development of three-dimensional space and the invention of linear perspective.14 He theorized that fifteenth-century artists placed polyscenic narratives in illusionistic space in order to imply the passage of time via movement in space, and that artists created simultaneous narratives in an effort to aid the functioning of memory, and thus make viewing an act of devotion.15 Alfred Acres expanded upon Andrews’s conclusion in his article, “The Columba Altarpiece and the Time of the World,” where he proposed that Rogier van der Weyden’s manipulation of time provided “openings” within the narrative that allow a viewer to meditate backwards and forwards through salvation history.16 Ultimately, the details link the events of the painting in biblical history to living experience; this pictorial process is similar to Memling’s and is essential to the narrative function of helping viewers experience revelation.17

Memling’s narrative scheme can also be disentangled in the light of narrative theory. In Six Walks in the Fictional Woods, Umberto Eco proposed an analysis that distinguishes three levels of narrative: story, plot, and discourse.18 For Eco, the story is the events as they occur in chronological order and the plot is the order in which these events are told, which might be rearranged to emphasize one or just a few events.19 Discourse is then the manner in which the story and plot are told so that they are understood in a particular way.20 Discourse is the active level of expression and interpretation; as such discourse is the element of narrative that leads the reader to better understand the author’s intent and the meaning of the narrative. In Eco’s model, the discourse helps the reader to understand the essence of the plot, elaborating upon its purpose. Paul Ricoeur’s work on narratology supplements Eco’s model.21 For Ricoeur, the story is a sequence of actions that cause a character(s) to change, or to which the characters react. He defines the plot as a nonchronological aspect that exists outside the episodic dimension of the story: it is a construction of meaning, the result of a “grasping together” of successive events that is very much bound up in the act of retrospection.22 It has the character of a judgment and involves encompassment. It requires a point-of-view and necessitates reflection.

Even though Memling’s narrative derives from the different gospels in the Bible, each with its own issues of story and plot, it can be analyzed on its own, regardless of its sources.23 The story in Memling’s panorama is the succession of vignettes that moves from the background to the foreground and back again, often skipping broad sections of time. One half of this story is given over to scenes from Christ’s infancy, and the other to events after his Resurrection. It begins in the left background with the Annunciation, then proceeds forward to the Annunciation to the Shepherds, and the Nativity in the left foreground (fig. 3). After that, it jumps to the center horizon to recount the tale of the Magi, where the three kings stand on the top of three mountains and look at the Star of Bethlehem. Their story continues as they move toward Jerusalem at the center; passing the scene of Herod meeting with the scribes before he has an audience with the Magi in the heart of the city.

The Magi then migrate toward the scene of the Adoration of the Magi in the foreground, before heading home again, moving toward the distant horizon on the right, where one can see the Embarkation and Departure of the Magi. The related story of the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt moves behind the shepherds, from the Massacre of the Innocents and Miracle of the Harvest in the left middle ground, toward the far left where the stories of the Fallen Idols and the Miracle of the Palm Tree appear (fig. 4). Memling’s story then skips ahead to the Resurrection in the center right foreground and meanders into the background with the different appearances of Christ, including Noli me Tangere, the Supper at Emmaus, and Christ Appearing at the Sea of Tiberias, concluding with the Ascension (fig. 5). The final events in Memling’s story concern the end of the life of the Virgin, cloistered at the right side of the painting. Chronologically, they begin with the Appearance of Jesus to His Mother in the middle ground, followed by Pentecost in the right foreground.24 We then move back again for the Death of the Virgin, and behind that her Assumption (fig. 6).

While Memling’s story might seem difficult to follow, his plot is clear. The key to the meaning of the painting is the plot, which Memling organized to emphasize the four scenes spread across the foreground of the panel–the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Resurrection, and the Descent of the Holy Spirit. He structured the plot this way because these four large and prominent scenes make direct reference to the major festivals of the Church (fig. 7). Keeping Ricoeur’s specifications for plot in mind, these four foreground scenes, and the Church festivals to which they refer, would have provided viewers the means by which, through retrospection, they could “grasp together” the other vignettes and construct meaning in the image.

Following Eco and Ricoeur, narrative discourse is the manner in which the story and plot are told so that the viewer is led to better understand the meaning of the narrative.25 For Memling the manner of discourse would be those descriptive details of the composition that are beyond what is essential to recount the events in the story. For example, the landscape setting helps reinforce the theme of the revelation of Christ as Savior of the world: the rock formations on either side of the Departure of the Magi shield them from the city of Jerusalem, thereby indicating the secret nature of the kings’ intent to avoid Herod and bring the news of the birth of Jesus back to their respective countries. Other details serve the plot established by the four foreground scenes–connecting those scenes to the immediate viewing context and the liturgical dramas taking place there. Significantly, the four main scenes and all but possibly one of the episodes connected to them in the background are the same as those that were enacted in late medieval liturgical dramas. Like the liturgical dramas that the clergy performed in the same space, Memling’s painted narratives helped a participant to visualize the sacred events that were the foundation for the solemn rites of the Church and to recognize anew the source of his or her own salvation.

The Rhetoric of the Landscape

Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ is one of the earliest extant panoramic landscape paintings, and while he did not invent the Simultanbild, Memling was one of the first to set it in such a wide, panoramic landscape. His work differs from early fifteenth-century German examples that set additional vignettes around images of the Crucifixion, such as the Wasservass Passion (fig. 8)26 or Konrad von Soest’s Crucifixion (parish church, Bad Wildungen). His work also diverges from earlier Netherlandish examples that relied more heavily on architectural structures to compartmentalize the scenes, such as the Southern Netherlandish Passion tapestry from ca. 1410–25 (Museo de Tapices de La Seo, Saragossa) or the Scenes from the Life of Christ by the Bruges painter Louis Alincbrot (fig. 9). Indeed Memling seems to have been the first to create a wide, unbroken view of the landscape that extends in all directions.

With Memling’s composition the landscape becomes so prominent that it attains a narrative function. His panorama is not simply a setting for the vignettes but is part of the narrative discourse. It has a job to do: it serves a plot that emphasizes the four major Church festivals, a theme reemphasized by the stage like settings and liturgical garments. He arranged the events that correspond to the four major Church festivals across the foreground, each carefully framed by natural and architectural structures. He then organized the rest of his landscape into horizontal zones that move back into space in a way that assists a viewer in dividing the narrative into sub- or concurring plot lines (fig. 10). Just beyond the main scenes, in the middle ground, are those stories that are secondary to the plot, including episodes from the liturgical rites that support the foreground liturgical event. Figures, roadways, and walkways meander from the foreground into the distance, creating narrative courses that Memling carefully separated from one another by mountains, rocks, city walls, and townscapes. The final zone includes the vast horizon of the panorama–the mountains and sea and all the tiny details that are barely visible to the naked eye. This is where the discourse of the painting moves out of the frame and into the future. Viewers can imagine themselves moving in time like the actors in Memling’s painting or the actors in the liturgical dramas, an effort which brings the lesson of the biblical event to their personal journey through time and through life. Memling’s sophisticated organization of vignettes creates knowledge and activates meaning. His pictorial arrangements make things explicit that are only implicit in verbal form, where the visual relationship of the vignettes and their proximity to one another emphasize ideas that are beyond the text.27

By separating the stories into sets that correspond to different liturgical events, Memling engaged his viewers on a personal level. He encouraged them to identify with the subjects, and to acknowledge the broad relevance of these to his or her own life. The visual journey in time through the twisted story enables this dual reaction in an audience and is crucial to the personal message of redemption.28 The panorama in Memling’s painting therefore substantially contributes to the narrative discourse by carrying the messages beyond the “text” to a viewer’s world.

The architecture and landscape in the foreground function on a metaphorical level in a rather standard fashion. For example, the broken-down stable symbolizes the deterioration of the Old Law with the Advent of Jesus, and the enclosed garden symbolizes the purity of the Virgin, who is essential to salvation history in this particular context. The landscape in the middle ground has a similar metaphorical function: Jerusalem, with Herod pictured inside, is the locus for the Old Law that will reemerge as the center for the New. The signifying function of the landscape then changes as one moves deeper into the background, the area that leads a viewer’s thoughts out into the world. Each mountain and king, together with the corresponding minute pictograph of a city, have a synecdochical function–they are representatives of entire continents and civilizations. So, too, the small expanse of sea, with the Magi’s ships sailing into the distance, representing a world of seas. In its entirety, the panoramic horizon symbolizes the rest of the Christian universe, including the heavens that open up in the sky to receive Jesus and the Virgin at the right. This area of the sky carries a viewer forward to the fifteenth century, joining him or her to the celebration of the liturgy in the church space.

In the Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ, the landscape does the hard work of the narrative discourse, allowing the viewer to follow the episodes of the story and grasp their broader significance. Each viewer is given a view similar to that enjoyed by the three Magi atop the mountains in the distance. Memling’s network of pathways and moving figures encourages a viewer to move within a panoramic model for the Christian world, built around the revelation of Christ and the salvation of humankind. A viewer sees the world from the perspective of a Christian who acknowledges the pivotal role of Christ and the Virgin. Through the process of looking this viewer can see the individual scenes and consider the role that the event had in the history of salvation and its relevance to his or her own life.

The Painting and the Liturgy

Scholars frequently have compared the vignettes in Memling’s Simultanbilder to public theater because they are suggestive of medieval stagecraft.29 The people of late medieval Bruges celebrated many of the events depicted in Memling’s narrative in the form of public theater and processions.30 The records of these performances help to reconstruct a fifteenth-century viewer’s experience with these subjects and what he or she might bring to a viewing of Memling’s painting.31 While Bruges was home to a major dramatic spectacle each year, its Holy Blood Procession, the official liturgical dramas staged in the church where Memling’s painting originally was displayed, are more relevant to Memling’s Munich panorama.32 While Memling’s audience brought their devotional experiences with public theater to their encounter with his painting, when they were in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, they witnessed and engaged with the official liturgical drama, which was an entirely different experience.

In order to understand Memling’s narrative strategy, it is important to recognize that the ideal viewer, what Eco might call a “model reader,”33 was one who viewed the Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk during each of the four Church festivals illustrated in the painting’s foreground. Such a viewer would have realized that Memling’s narrative structure, the four main scenes and the episodes connected to them, are the same as those being enacted within the building where the painting was hung. Indeed all but one episode shown is included in some extant example of official liturgical dramatics performed during each of the four major religious holidays signaled by the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Resurrection, and the Descent of the Holy Spirit in Memling’s image.34

The clergy generally performed in the liturgical dramas, which were sung in Latin, and most dramas followed the framework of the liturgy, which combined music and drama in a way that could blur the distinction between the ritual and theater.35 No two versions of a given liturgical drama are identical, and each records local preferences and practices.36 Liturgical plays are recorded in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk going back to the early fourteenth century, but the dramatic texts themselves apparently are lost. Nevertheless, we can piece together some idea of those performances by looking at extant liturgical dramas from other churches and monasteries in Bruges and other cities in Western Europe.37

Inherent in all of the extant liturgical dramas was the simultaneous visibility of all the events.38 The presence of actors in the vicinity of the playing space who do not participate in a given scene is a characteristic of medieval staging.39 Liturgical theater was polyscenic, just like Memling’s painting. Also similar to Memling’s painting is the thematic focus on revelation. Lynette Muir wrote that the dialogue sung at the beginning of Easter Day Mass–the Quem queritis? (Whom do you seek?) and its answer, Jesum Nazarenum, O celicole (Jesus of Nazareth, O heavenly ones)–generates the mystery and revelation of the religious rite.40 The Church reused this brief exchange in a variety of liturgical contexts over the following centuries, and revelation remains the goal of these other dramas, each of which appears as part of the celebration on the four feast days accentuated in Memling’s narrative structure.

Advent begins the liturgical year, and the Nativity with its corresponding episodes is the first important event in Memling’s plot.41 The Annunciation is the first episode from that story; it obviously came much earlier, and its feast day normally falls on March 25. But many European churches, including Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, St. Donatian, St. Gilles, and St. Savior’s in Bruges, moved the celebration of the Annunciation to the Advent season, either on December 18 or on the Wednesday of Ember Days before Christmas.42 Memling did the same thing in his panorama, adhering to his local liturgical calendar rather than the chronology of the story from the Scriptures.43

Only three official liturgical plays of the Annunciation survive, one of which comes from sixteenth-century Tournai.44 That manuscript describes two platforms with curtains that the clergy placed on either side of the high altar, one for the Archangel Gabriel and the other for Mary, who had a cushion to kneel upon as she read. After a mass was sung, the curtains were pulled away to reveal the clerics playing Gabriel and Mary. The celebrant or deacon would sing the narrative part of the gospel, and the clerics then sang their words in turn. When the wordsSpiritus Sanctus super veniet in te (The Holy Spirit will come upon you) were spoken, someone lowered a dove on a cord with candlesover Mary’s head.45 Memling’s image of the Annunciation also includes a double arcade, and Gabriel is shown wearing liturgical garb as the dove of the Holy Spirit descends. These liturgical references help convey the mystery of the Eucharist46 and would have helped involve a viewer in the liturgical event and prompted him or her to consider its greater meaning of the revelation of Christ as Savior.

The story of the Nativity and the Annunciation to the Shepherds are the two episodes in Memling’s painting that are associated with liturgical plays from Christmas Day.47 Twenty manuscripts with that drama, called the Officium Pastorum, survive, dating back to the eleventh century.48 In these plays, the high altar stood for the manger, and the focus was again upon discovery and revelation of the infant son of God.49 Typically, as is evidenced in fourteenth-century liturgical manuscript from Rouen, an angel announced the birth to shepherds, who then walked toward the high altar. In the Officium Pastorum manuscripts the Quem queritis? dialogue from the Easter liturgical drama appears as a standard feature, with the choir singing to the shepherds, Quem queritis in praesepe, pastores, dicite? (Whom do you seek in the manger, shepherds, say?), to which the shepherds reply, Salvatorem, Christum Dominum infantem pannis involutus secundum sermonem angelicum’(The Savior Christ the Lord, a child wrapped in swaddling bands as the angels said).50 As in the Annunciation drama, the action of the liturgy was organized so that the actors suddenly revealed Jesus to the audience.51 Again Memling reemphasized the common Eucharistic meaning of the Nativity, this time by drawing a parallel between the Infant Christ and the sheaf of wheat in the foreground.52

In the late Middle Ages Epiphany was a more sacred and elaborately celebrated holy day than Christmas because it was the manifestation of Christ to the world and as such it was the most important feast day of the year.53 The purpose of its liturgical celebration was to commemorate this recognition of Christ as the Savior, and so the liturgical dramatization of the Magi’s story, the Officium Stella, again focuses upon revelation with the now ubiquitous trope, Quem queritis?54 Without a doubt, the dramatics for the Officium Stella were the most elaborate in the late Middle Ages, having the most theatrical elements,55 but initially only the Magi’s journey was dramatized. This was the case for a Epiphany performance from 1330 in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, where the three kings, represented by boys, offered their gifts at the high altar, singing the antiphon Hoc signum; thereafter, the choir sang the antiphon Tria sunt munera.56 By the fourteenth century, the Officium Stella had expanded to include the story of Herod, including the meeting between Herod and the Magi, the angel’s warning to the Magi, and the Massacre of the Innocents.57

In accordance with the significance of this holiday, the Adoration of the Magi and related episodes occupy the largest part of Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ, with nearly two-thirds of the painting dedicated to these events.58 His expansion of the narrative and his choice of individual scenes mirror the liturgical dramas performed on Epiphany. To the left of the Magi’s departure is the Massacre of the Innocents and the related scenes of the Miracle of the Harvest, the Fallen Idols, and the story of the Miracle of the Palm Tree; while these events relate to Innocents’ Day, December 28, they were performed, as they are in Memling’s painting, as part of the story of the Magi on Epiphany.59 The artist connects these different episodes by a network of roadways and moving figures that further correlates with the movement of the performers between these scenes in the church.60

The liturgical celebration of Easter was actually the first that the Church expanded into drama, and it remains the best documented in text.61 This drama established the pattern for the Quem queritis? dialogue and the focus upon the revelation, which became a fixed feature in the other liturgical dramas.62 The earliest plays simply dramatized the visit of the three Marys to the sepulcher of Jesus, usually staged at the high altar of the church, where a cross was “buried” on Good Friday and “resurrected” on Easter morning.63 Sometimes curtains surrounded the altar, and less often a temporary structure covered it. The Marys would move to the altar from a short distance away, hear about the Resurrection, and reveal the empty grave cloth to the congregation.64 Amysterium resurrectionis may have existed already in Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk by 1350, and in 1432 there is a record of payments the church made to actors playing Jesus, Mary Magdalene, two other women, an angel, and Thomas, among others.65

While the Easter play began with a dramatization of the story of the three Marys, it also came to include other episodes, such as the Supper at Emmaus Christ’s meeting with Mary Magdalene, or Noli me Tangere.66 There are thirteen extant texts of Emmaus plays, thePeregriunus, dramatizing Jesus’ meeting with Cleophas and Luke, the supper at Emmaus, and again the theme of revelation at that meal.67 By the late Middle Ages in Rouen, the stagecraft included a “room,” raised on a platform with chairs, to represent Emmaus.68 In Memling’s painting, the episode is staged similarly and includes details like the liturgical vestments that are a part of the discourse, referring as they do to the liturgical experience.

The Easter liturgical season concluded with reenactments of the Ascension, and this event is also pictured by Memling.69 Extant stage directions from the late Middle Ages for the liturgical celebration of the Ascension are rather elaborate.70 In Moosburg in the fourteenth century, clerics raised an effigy of Jesus as they lowered an angel, while other clerics representing Mary and the Apostles surrounded the area in a circle.71 The medieval drama required that, like the Virgin in Memling’s image, Mary wear the headdress of a widow.72 In the image and the liturgy, this event ends the celebrations for this season. Correspondingly, in Memling’s painting the Ascension leads the narrative into the sky and out of the picture.

The last events of the liturgical year that Memling painted in his Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ are all associated with the Virgin. These images are clearly and carefully confined to architectural spaces at the right,and each event pictured in this part of the painting was celebrated within the liturgy on or in connection with Pentecost. The sequence begins with the scene in the foreground, the Descent of the Holy Spirit.73 This image illustrates the events of Pentecost, the seventh Sunday after Easter, which is the last important festival of the Church year before the cycle begins again in December. The surviving liturgical plays record different ways of dramatizing the Descent of the Holy Spirit; the clergy of Bruges’s St. James Church used a dove to symbolize the Holy Spirit in 1464.74 Memling’s sequence ends with the Assumption of the Virgin, and that event also marks the end of the Church’s important festivals for the liturgical year.75 In Bruges, the clergy sang a magnificent antiphon on the day of the Assumption at Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk.76 Elsewhere the day was celebrated with liturgical dramas that adopt the Quem queritis? trope from the Visitatio Sepulchri.77 In Memling’s painting, this final image leads a viewer up and out of the painting to end the story.

The Appearance of Christ to His Mother is the only episode in Memling’s entire composition that does not clearly correlate with liturgical dramatics. It is also the only scene that appears out of chronological sequence: Christ first appeared to Mary after the Resurrection, before he appeared to anyone else, but Memling repositioned the episode at the “end” of the story, after the Ascension. Perhaps Memling included it in this position to be a mirror image of the Annunciation. These two events mark the first human and divine appearances of Jesus, and their arrangement also sets the entire liturgical cycle of the year in a Marian context, ultimately emphasizing her essential role in redemption.78

Conclusion

Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ, his Simultanbild, with its broad panorama and winding stories seems to be an endless tangle of tributaries that flow without any rhythm or rhyme, but nothing could be further from the truth. Memling painstakingly executed his vast, detailed, and complex composition so that a fifteenth-century visitor to Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk could experience revelation just as he or she did when witnessing the liturgical dramas during the four major festivals of the Christian year. It was not enough for Memling to illustrate the singular events–the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Resurrection, and the Descent of the Holy Spirit–that visitors to the church celebrated during the festivals. Engaging the audience to experience and reexperience revelation as it pertained to these events in an ideal manner required much more of the liturgical drama and much more of Memling. The fifteenth-century audience could be ushered toward the events central to the plot of the painting and the liturgical drama by the vignettes that wind their way through the middle ground of Memling’s expansive landscape or the liturgical dramatics moving down the aisles of the church. Either way, they would arrive at revelation. With the help of Memling’s structured panoramic landscape, viewers could move toward the sunset on the horizon and carry the message to another time and another place. The simultaneous narrative set in the panoramic landscape with the goal of renewing the process and history of salvation through revelation was Memling’s invention.