Identifying Jan van Eyck as Hand G of the Turin-Milan Hours depends substantially on the identification of Duke John of Bavaria as sometime owner of the manuscript. Although the Turin-Milan Hours contains the arms of Hainaut, Holland, and Bavaria, the duke had legal claim only to parts of Holland. Neither the Estates of Hainaut nor Countess Jacqueline of Bavaria, heiress of John’s brother, recognized his sovereignty in Hainaut. The arms on fol. 93v are likely those of the still-unknown owner. The manuscript was probably finished in one campaign circa 1450 in Bruges, not in the several campaigns of work that scholars have usually proposed. Jan van Eyck was therefore not among the illuminators.

The manuscript known as the Turin-Milan Hours needs only a brief introduction to the readers of this journal. This book of prayers and masses for lay use forms part of an originally larger manuscript containing prayers for the liturgical hours and other occasions.1 This larger manuscript of about 350 leaves was initiated circa 1385–90 or shortly afterward. Albert Châtelet and Maurits Smeyers have suggested that from the start, this manuscript’s parts—a book of hours finished by 1410 and a calendar with images of a later date (now Bibliothèque Nationale de France, nouvelle acq. lat. 3093), plus leaves completed after 1410 that are housed elsewhere—were meant to be complementary but separate volumes,2 since a single thick book would have been unwieldy to bind and use.

The Turin-Milan Hours is the name given to leaves in two volumes. One, containing prayers to be said during masses and during the liturgical year, entered the Trivulzio Library in Milan from the Agliè collection and is now in the Museo Civico d’Arte Antica of Turin (inv. no. 47). The second, containing calendar and prayers, was housed circa 1720 in the royal library of King Victor Amadeus of Savoy (as Ms. 34)3 and later in the Biblioteca Nazionale e Universitaria in Turin (as Ms. K. IV. 29); these leaves were almost completely destroyed by fire in l904.4 Additional leaves are in the Louvre (inv. nos. RF 2022–2025) and the J. Paul Getty Museum (Ms. 67; this leaf originally appeared after fol. 75). I follow here the universal practice of referring to the Milan and Turin portions of the manuscript, no matter where the pages are now.5

Distinguished scholars have claimed at least five and sometimes seven of the Turin-Milan Hours’ painted leaves for Jan van Eyck, postulating that they were created when he worked for Duke John of Bavaria at the latter’s court in The Hague in 1422–24.6 Fewer scholars have held that these leaves postdate the artist’s death in 1441.7 In this essay I will support the minority view by disconnecting the manuscript from Duke John of Bavaria, redating the calendar in Turin to the period before Jan van Eyck’s arrival there in the 1420s, and proposing that was only one campaign of illustration, circa 1445–52, after Van Eyck’s death.8

By 1413 Jean de Berry had traded a “tres belles heures de Nostre-Dame, escriptes de grosse lettre de forme, declairees ou IIc XLIIIe fueillet du livre desdix comptes precedens” to Robinet d’Estampes, his garde des joyaux, in exchange for another book.9 Our manuscript has been connected to this courtier because the arms of a female member of the Beauvilliers family, perhaps Marguerite, later Robinet’s daughter-in-law, appear on page 2 of the portion in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (fig. 1).10 Another Beauvilliers lady could, however, have bought the manuscript.11 Smeyers proposed that the larger manuscript, containing the Turin-Milan Hours, was auctioned with other ducal goods when Jean de Berry died in 1416 and was not given to Robinet as a gift.12 He denied that this manuscript was the duke’s “tres belles heures” because ducal inventories always indicated if a manuscript consisted of more than one part; since only one part was recorded for the “tres belles heures,” it should not be our manuscript, which has two parts. However, since many leaves in the second part lacked images, it must have remained unbound. The first part thus may still be the manuscript listed in the duke’s inventory. No one knows where the Turin and Milan portions were before they reached Turin (by 1720) or entered the Agliè collection (by the mid-nineteenth century).

Other scholars maintain that both the calendar and the text of the Bibliothèque Nationale portion of the manuscript were made for Jean de Berry, although the calendar postdates the initial project. It is written on thinner parchment with more lines per page, smaller letters, and less decoration than we see on the other leaves. The calendar contains references, ending in 1404, to the duke’s family, and it includes Saint Hilary of Poitiers, a saint pertinent to the duke and his lands. Millard Meiss summarized other reasons for identifying this manuscript as the duke’s Très Belles Heures de Nostre-Dame: the text is written in the type of letters described in the ducal inventory and not seen in any other known and eligible manuscript; the manuscript in Paris contains the duke’s portrait and his arms in a picture of a funerary chapelle ardente; and a relative of Robinet d’Estampes owned it.13

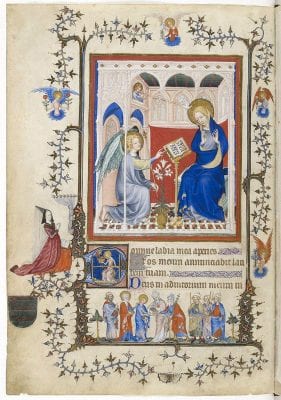

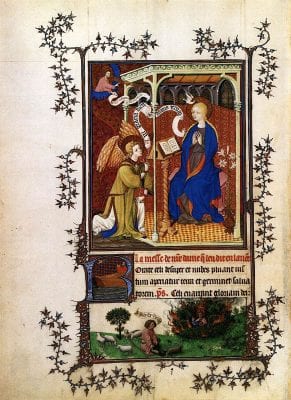

Since the early twentieth century, the calendar in Turin, the seven miniatures, and some bas-de-pages in the portions in Milan and Turin have often been dated between 1417 and 1425. Georges Hulin [de Loo] attributed the images to Hand G, one of the manuscript’s anonymous miniaturists, whom he labeled Hands A through K. Hands A through E worked before 1410 and do not concern us; much of their work is in the Bibliothèque Nationale portion of the manuscript. The artists grouped as Hand F depended upon the Bedford Master, an artist employed in Paris by John, Duke of Bedford, who was regent of France between 1422 and 1435; the Bedford Master’s followers or former associates can be traced into the 1460s, as can their movement into the Low Countries.14 Hands G and H are related in style to Jan van Eyck and may earlier have worked as helpers in his atelier. Three miniatures given to Hand G are in the surviving Milan portion, while the other four were destroyed in Turin two years after their publication in black and white.15 Hands I, J, and K are universally thought to have worked in the 1440s.

The connection of Jan van Eyck to this manuscript in the early 1420s is based on the presence of Eyckian stylistic elements and supported by circumstantial evidence. Those stylistic elements could have originated with Hubert van Eyck, but miniatures given to Hand G depend upon models that postdate Hubert’s death in 1426.16 The Eyckian elements include deep space accommodating well-populated scenes, a harmony of rich colors emphasized by delicate atmospheric and light effects, extraordinary detail, including reflections on metal, and the supposed intellectual sophistication of the content in two images—Cavalcade on the Seashore (fig. 2), and The Birth of Saint John the Baptist (fig. 3).17

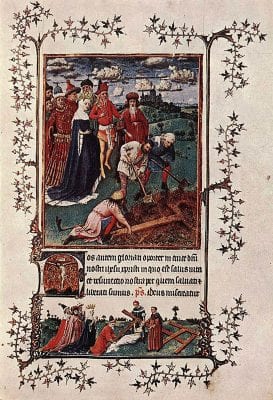

Those who attribute the manuscript to Jan van Eyck often place its creation during his service as varlet de chambre to Duke John of Bavaria (died 1425), between 1422 and 1424.18 Historical and circumstantial evidence seems to corroborate that attribution: the arms of Bavaria quartered with those of Holland and Hainaut appear in reverse on a banner in the seaside cavalcade on Turin fol. 59v. A second miniature showing mourners around a coffin under a chapelle ardente in a church choir (fig. 4) includes arms that Paul Durrieu recognized as those of Hainaut and Holland, though not of Bavaria (fig. 5). John’s father, Duke William VI of Bavaria-Straubing-Wittelsbach, who was also Count of Holland, Zeeland, and Hainaut (died 1417),19 had inherited Hainaut and other territories from his father, Duke Albert I. The praying leader of the cavalcade wears the collar of the Order of St. Antoine de Barbefosse, an order that Albert initiated.

Scholars who date Hand G’s miniatures to 1422–24 because of the heraldry on the banner and the catafalque also connect the calendar destroyed in Turin (fig. 6) to Hainaut, since its saints would be suitable for an owner in Hainaut, which John claimed. The belief is that the calendar was originally meant for Hainaut, and that the entire original manuscript was perhaps intended as a gift for one of Jean de Berry’s relatives there, although the gift was neither completed nor given in his lifetime. Duke Albert is one potential recipient; he died in 1404, when the last death notice of Jean de Berry’s relatives appears in the calendar attached to the Bibliothèque Nationale manuscript. Albert’s lands included two dioceses in Hainaut, and as a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, he was also engaged with the neighboring territories.20 Sometime early in the fifteenth century work on the manuscript halted and is thought to have resumed at John of Bavaria’s court in The Hague.

The connection between a possible Hainaut owner of the manuscript and John of Bavaria is tenuous, however. As has long been acknowledged, the French royal arms seen on Turin fol. 77v do not indicate a French king’s ownership nor do the arms in the background—those of Brabant, Charolais, and Burgundy—indicate ownership by Philip the Good, since he became duke of Burgundy only in 1419 and this page does not antedate 1419.21 The meaning of all these arms is now lost, as is that of the arms of France and Flanders in the bas-de-page, where they float above armies fighting oriental enemies. The arms shown on Turin fol. 59v (see fig. 2) and Milan fol. 116 (see fig. 4) need not indicate ownership, either: they appear in scenes of past public events. The main image on Turin fol. 59v accompanies a king’s prayer, but no king is shown. Furthermore, William and John, along with the local nobility, must have been members of Albert’s Order of St. Antoine de Barbefosse, but no one else in the cavalcade wears that collar. The events alluded to in this manuscript need not be close in date to the manuscript’s painting; Smeyers pointed to the Montfort Hours of circa 1450 (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibiliothek, Cod. S.N. 12878), where fol. 62 portrays Jacqueline of Bavaria, who had died in 1436.22 The banner on Turin fol. 59v probably refers to William, who was dead when Jan van Eyck worked for John of Bavaria, William’s brother. For reasons now lost, the banner was meant either to commemorate William’s deeds and, on Milan fol. 116, his death, or else the artist appropriated these compositions for new purposes. Hand G may have found these scenes suitable for conversion to related subjects or used them because the patron of the later phases of illustration had a connection to William’s house.

A connection of the calendar to Hainaut is also far from certain. Many saints named on the rectos (the only sides of the leaves photographed in 1902) were also venerated in the dioceses of Münster, Cologne, and Utrecht,23 and Waudru, Hainaut’s important local saint, is missing.24 Hulin noted Saint William’s absence from the calendar, although Jacqueline’s father, William, ruled Hainaut. A later owner who obtained this calendar and part of the manuscript could have found most of his local saints in it. Anne van Buren suggested that “if the book was still intended for use in worship, the patron was not expected to pay much attention to the calendar.”25

A date of circa 1420 is, moreover, too late. The calendar is instead coeval with the initial creation of the manuscript. Its frames and format match those of the other illuminations. The borders and script differ from some others only in omitting small figures and angels near the ivy sprigs that appear in the Bibliothèque Nationale portion of the manuscript. But angels are also missing from most leaves in the Turin and Milan portions, even though the pages were prepared and supplied with text before any miniatures were begun. Angels are also missing from most leaves with miniatures by the artist active before 1420 who painted Turin fols. 78v and 80v and Milan fols. 1v (fig. 7), 16v, 20v, 90, and 106. The Turin calendar’s borders are less lively than those of some other pages, but no more static than those of page 194 of the Paris manuscript, Turin fol. 14v, and Turin fol. 75v—each thought to have been given miniatures, initials, and bas-de-page images at different times. Since the borders in the Bibliothèque Nationale’s portion are not uniform, either, a modest change in pattern does not denote a change in date. The calendar’s lettering also appears contemporary with that of the rest of the manuscript. To create the calendar pages in the 1420s, those who assembled the manuscript would have had to locate or commission pages of the right size, whether blank or with existing frames. By the early 1420s, this style of border design was outmoded, although an older artist could have reproduced it; the scribe, too, would have had to imitate models of decades earlier.

It is therefore more plausible to date the Turin calendar to the time when the manuscript was first prepared. It was not bound with the Bibliothèque Nationale’s portion because of errors in numeration and because the bas-de-pages were not yet painted.26 If the manuscript in Paris was assembled quickly, an existing calendar referring to the Duke of Berry’s relatives might have been preferred despite its different lettering and lack of room for bas-de-page images.

Accepting the Turin calendar as original to the initial phase of the manuscript eliminates the need to explain how and why anyone around 1420 would copy an earlier page format and older borders. A coordinator of work at that time would surely not have ordered painstaking imitations of older frames without providing for their efficient completion with bas-de-page images, but the bas-de-page scenes clearly postdate 1440. As for missing angels, a few marginal figures among the spiky fourteenth-century-style leaves could have been copied easily and quickly from other pages if anyone cared to do so. Only one artist in a later campaign did. The Turin portion’s first miniature (fol. 14, fig. 8), includes an angel in the style of the 1440s in the left margin, an idea evidently derived from earlier half-angels, such as those on Turin fol. 39v or Milan fol. 4 (fig. 9).

The Turin calendar margins are therefore original ones that lacked bas-de-page images. After one artist in the later 1440s experimented with enriching the border on Turin fol. 59, everyone abandoned efforts to modernize the older marginal decoration. I conclude, then, that neither the surviving calendar in Paris nor the burned one in Turin supports a connection to Jan van Eyck at the court of John of Bavaria or a campaign of work in the 1420s.

The manuscript’s connections to Hainaut and to John of Bavaria are as questionable as was John of Bavaria’s rule over Hainaut. John resided in The Hague after ousting his niece, Jacqueline of Bavaria, from parts of her inherited lands in Holland and Zeeland, and after claiming Hainaut.27 William of Bavaria had willed his territories to Jacqueline, his sixteen-year-old daughter, bypassing John, his brother. But when William died in 1417, John of Bavaria attempted to usurp his niece’s patrimony, and Sigismund of Hungary, king of the Romans (later Holy Roman Emperor), agreed that John was William’s proper heir, since Holland and Zeeland were held in fief from the Holy Roman Empire in which women could not inherit land. But the empire’s rule had been broken before and Hainaut did not require male succession.28

In order to overcome the prohibition against female succession in Holland and Zeeland, Jacqueline married Duke John of Brabant. Since John of Brabant was Jacqueline’s cousin and her mother’s godson, only a papal dispensation could permit the marriage. Pope Martin V signed dispensation on December 22, 1417 but revoked it fourteen days later.29 A council of nobles in The Hague during that month held the marriage to be permissible, since functionaries had not affixed the papal seal to the revocation until after the betrothed couple received their dispensation.30 Jacqueline married John of Brabant at court on March 10, 1418, and on April l0 in church.31 This made John of Brabant governor of Jacqueline’s territories on her behalf, even though Sigismund claimed the authority to confer Hainaut, Holland, and Zeeland upon John of Bavaria.32 Only three cities and some territories in Holland and Zeeland accepted John of Bavaria’s rule, and all of Hainaut refused,33 leaving his right to display the arms of Hainaut and Holland in doubt, despite his de facto rule over parts of Holland and Zeeland.

John of Brabant, characterized by Burgundian chronicler Enguerran de Monstrelet as “weak in body and mind,”34 feebly tried to stave off John of Bavaria’s military incursions by signing the Treaty of Woudrichem in 1419, giving the two Johns shared governance of Holland, Zeeland, and Hainaut until 1424.35 Jacqueline objected to the treaty and to subsequent secret negotiations between the two Dukes John, as did many of her subjects. She fled to Hainaut, where she convened the Estates to present her grievances. Despite Sigismund’s endorsement of John of Bavaria as William’s heir in Holland and Zeeland, Hainaut did not require a male ruler. Jacqueline became convinced that her marriage was invalid, and that John of Brabant consequently had no right to sign agreements regarding her lands. She crossed the English Channel in early March 1421 to seek English support for her cause and was met at Dover by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother to King Henry V.36 In England she received an annulment or some form of divorce from the anti-Pope Benedict XIII37 and then married Humphrey by October 25, 1422.38 Pope Martin, however, affirmed on May 27, 1424, that Jacqueline was legally still married to John of Brabant.

During this time, John of Bavaria’s hold on some parts of Holland and Zeeland was in doubt legally, and he still did not rule Hainaut, although he did exercise distant authority over it through John of Brabant in Jacqueline’s absence. Humphrey and Jacqueline invaded Hainaut in October 1424 and by December 5 had secured the Estates’ recognition of Humphrey as Count of Hainaut and regent on his wife’s behalf. The Estates released John of Brabant from his earlier oaths regarding governance of the county, thereby denying him the right to treat with anyone about Hainaut. At least from the Estates’ viewpoint in late 1424 neither Duke John ruled there legitimately, although any enthusiasm for Humphrey and Jacqueline was tempered by fear of fighting and disruption to commerce in the towns. Parts of the rest of William’s territories remained loyal to Jacqueline, who was consistently called Countess of Hainaut, sometimes also—in England—Duchess of Holland.39

Because of this history, one may doubt that John of Bavaria included the arms of parts of a disputatious territory in a miniature made for him, even if he claimed authority over them. Moreover, the miniatures’ arms omit Zeeland, another of his disputed lands. John may have styled himself “sone van Henegouwe van Hollant ende van Zeelant,” but that expression had no status or authority in Hainaut (Henegouwe), where Jacqueline and her new husband still held the title of count and countess.40 John also issued coins to proclaim himself “Dux Bav et filius Holl” (Duke of Bavaria and Son of Holland), but those coins do not mention Hainaut and were issued only in Luxembourg, which he ruled through Elisabeth of Görlitz, whom he had recently married.41 Indeed John of Bavaria’s possession of Holland, Zeeland, Hainaut, and Frisia was so incomplete that he is unlikely to have ordered only the arms of some of Jacqueline’s territories to be depicted in a manuscript made for him, rather than the arms to which he was clearly entitled by heredity. John could have specified the inclusion of the arms of more compliant territories or those that he and his wife, Elisabeth of Görlitz, clearly owned and ruled. All this makes doubtful the identification of John of Bavaria as patron of the Hand G miniatures that inconsistently include the arms of Hainaut and Holland.

***

Who, then, owned the manuscript? L. M. J. Delaissé proposed a nobleman at the Burgundian court, Frank van Borsselen (1396–1450).42 In 1428, Jacqueline, abandoned by Humphrey and the pope, became a prisoner of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy, in which duchy she married Van Borsselen in 1432. She was forced to declare Philip her heir and died childless in 1436. Delaissé proposed Van Borsselen as the final patron in a campaign of work done between Jacqueline’s death in 1436 and 1445 (see fig. 3; the arms could have been placed on her catafalque to show the extinction of her line), when he received the Order of the Golden Fleece, which does not appear in the patron portraits in this manuscript. Alternatively, Van Borsselen could have acquired the unfinished Turin-Milan manuscript through Elisabeth of Görlitz, if she had inherited it from her husband. Shortly before 1439, Van Borsselen became the temporary receiver of Elisabeth’s valuables, but she retrieved her property in 1441 or 1442 in exchange for land.43 If Elisabeth of Görlitz left the unfinished manuscript behind when she moved from Burgundy to Trier, it could have been returned to Van Borsselen, who would then have altered an earlier program of painting to emphasize his and Jacqueline’s history.44

Nevertheless, nothing but the questionable heraldry indicates that John of Bavaria or Elisabeth or Van Borsselen ever owned the manuscript. Van Borsselen is known only for commissioning metalwork, and later stained glass,45 and his arms are not shown in the manuscript. No evidence connects him or Jacqueline to its ownership even though the armorials on Turin fol. 59v and Milan fol. 116 relate to the House of Holland-Bavaria, to which she belonged. Only one owner was depicted in the 1440s (or even the early 1450s): a young man shown at prayer in several initials (Turin fols. 14, see fig. 8, 60v, Milan, fol.124, fig. 10), in two large miniatures (Turin fols. 46v, 47v), and also on other leaves. His clothing varies, but it could be the same man with costumes differentiated by the artists’ ideas about suitability for the context. This man is far too young to have been Van Borsselen after Jacqueline’s death in 1436—the only time he could have had himself alone presented as owner.

If we look for heraldry to identify the young man, that of Milan fol. 93v is more promising. Unexamined in detail since Hulin wrote a footnote about them are tiny coats of arms in the window of John the Baptist’s birth room (fig. 11).46 At the viewer’s right the arms are or à trois boules (or tourteaux) gueules. The only family known to have used three red boules on gold in the fifteenth century was that of the Gronsveld, whose lands lay in the Duchy of Limburg, across the Meuse from Maastricht. I have not been able to identify a female member of that family who would have had a young adult son in the late 1440s or just afterward, but the family is not fully recorded in reliable sources.47 Several families used three red disks (tourteaux) on gold in the fifteenth century. The most likely from a geographic viewpoint are the Doncourt of Flanders and the Thévenin de Tanlay of Burgundy.48 At the viewer’s left, we now see only blue, and no family using azur plein is known to have married a Gronsveld, Doncourt, or Thévenin, although the records are fragmentary. Hulin referred to “azur à un meuble indistinct d’argent (la harpe de David?).” He identified the base of the other arms as argent, so unless he was referring to silver foil representing window glass, he did not have the leaf at hand when he wrote the description and could have made more than one error. David’s harp is irrelevant symbolically, as this scene does not refer to Mary’s ancestry.

Another reason for preferring the owner of these arms as patron of the manuscript is that the arms are small but painstakingly executed, and in precisely the place where fifteenth-century people placed their heraldic devices.49 James Marrow, noting other arms in the manuscript, concluded that neither those arms nor the ones in the window could be used to identify the manuscript’s patron.50 But arms in a window, painted minutely with considerable effort, and on the first page of the suffrages, differ in function from those in scenes of public activity.51

Most scholars separate the campaign of decoration that included the Birth of Saint John the Baptist from the campaign that produced the images of the young man, but it is likely that Hands F through K worked at the same time. Eberhard König and Albert Châtelet explained the arrangement of quires and offered ideas about the various artists in each quire.52 While most scholars believe that the later parts were painted in several temporally discrete campaigns, the visual differences may have another explanation: miniaturists of different origins at work simultaneously could finish work started by others, share workshop models, or take ideas from leaves painted by someone they knew.

All scholars agree that several artists collaborated on individual pages. The miniature of Saint Julian (fig. 12), for example, with its moving waves and attention to landscape, is artistically superior to the bas-de-page that shows Julian hunting on a stiff horse in monotonous terrain. Work by the Bedford group, Hulin’s Hands F 1–3, is now often thought to be contemporary with pages painted by G (seen as one person), and perhaps also H, I, and J, although there is little agreement about how early H, I, and J were active or how many individuals should be included under those letters.53 I and J are sometimes conflated. Everyone agrees that the latest images were executed by the K artists circa 1445 or soon afterward (see fig. 4). Within the K group, several scholars distinguish two tendencies, one related to an artist known as the Llangattock Master (Anne van Buren’s Master of Folpard van Amerongen) and the other to an artist affiliated later with the circle of Willem Vrelant (although the figure styles differ from Vrelant’s).54 The K group is distinguished by spacious settings, lively and detailed storytelling (often of unusual subjects), a prosaic approach to the events depicted, and unrefined but usually energetic execution.55 While F through J might have slightly preceded the K artists, we shall see that the process of painting suggests that K completed a painting campaign and did not inaugurate a later one. It would be tiresome to repeat the various attributions to each hand; Delaissé commented that “to judge from Hulin’s publications, no other manuscript could so often have left the hands of its successive owners to be illuminated by such an unbelievable number of miniaturists.”56

The number of miniaturists is believable if we count workshop assistants as well as masters. Several small ateliers, working collaboratively, could have finished the manuscript efficiently for one patron in one campaign shortly before or after 1450. This kind of effort was made earlier as well as at mid-century.57 In Bruges, there was probably a street or district where miniaturists and manuscript craft workers lived near each other, as there was in Paris.58 Workshops joined forces to execute commissions that one workshop could not finish efficiently. Miniaturists might even have solicited assistance from unemployed painters of small panels who could work on parchment or vellum.

Delaissé suggested that we ask questions about the manuscript’s final owner and the sense that the manuscript might make as a totality.59 Would the final owner want to glorify his family, emphasize his piety, his personal history, or his territories? Now we may ask: Could an interim owner in a long series of owners have done any of this if he bought a manuscript only partly finished by various hands? If there were multiple campaigns of illustration, did the artists follow subjects originally specified, and if so, how did they learn what the subjects were? To deal with these difficulties, we recall Delaissé’s doubts about the number of campaigns. I propose that after the manuscript was divided, with part of it bound as the present Bibliothèque Nationale de France, nouvelle acq. lat. 3093, there was only one campaign of work, with appropriate subjects specified by the organizer of the work, such as a libraire.

Imagining a single campaign with a multitude of executants employing various styles solves several puzzles. First, the Hand G pictures do not fit into Jan van Eyck’s known career, a question that has perplexed every scholar. Second, all the artists’ groups except those around Hand F (Bedford) derived at least some inspiration from panel paintings in Jan van Eyck’s circle. Even F may have absorbed aspects of Jan’s rounded modeling. Third, Hand G painted late enough to have known two pictures by Rogier van der Weyden from the second half of the 1440s or slightly later.60 Fourth, the illustrative program may have been devised around the time when the vernacular translation of the Speculum humanae salvationis was completed in 1446; Smeyers pointed to this connection.61 Fifth, the traditional history of acquisition and decoration in multiple campaigns seems excessively complicated. Sixth, when Hulin saw the Turin portion, he noted that metallic details were not tarnished.62 This detail suggested to him that the manuscript had not often been opened and used.

If Jan van Eyck is not Hand G, then the first puzzle is solved, and the others fall into line.

As for the second puzzle, the Hand F (Bedford) artists declined to copy Eyckian models, perhaps because they considered their originally Parisian ones to be superior or at least acceptable for patrons in the Low Countries. It was also easier to use familiar models than to adopt new ones. Maurits Smeyers and Bert Cardon wrote of “work sketches which probably remained in circulation for thirty years.”63 Group F apparently had no opportunity to imitate Eyckian paintings. These artists were employed only to paint bas-de-pages and to modernize existing older miniatures.

Miniatures made from Eyckian models were most likely executed in Bruges, where those models were available, as were other panel paintings, and miniatures from Utrecht and Paris. Petrus Christus also worked there, and Turin fol. 14, the first miniature in that section of the manuscript, has been attributed to him (see fig. 8).64 The imitation of entire panel painting compositions differs from borrowing individual motifs and suggests new ideas in workshop practice in which complicated pictures were copied for eventual reuse on both panels and manuscripts.65

Separating Jan van Eyck from Hand G also solves the third puzzle: how the miniaturist could have painted late enough to have known two works by Rogier van der Weyden that postdate Van Eyck’s death in 1441. One is the three-part composition showing the life and death of John the Baptist (fig. 13) and the other is the Seven Sacraments altarpiece commissioned by Bishop Jean Chevrot of Liège circa 1446 (fig. 14).66 Chevrot also commissioned the Cité de Dieu manuscript (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale Albert I, Ms. 9015-9016) dated 1445, in which the frontispiece (fig. 15) shows the hill and tree of Turin fol. 59’s bas-de-page (fig. 16) as well as the cityscape of the Rothschild Madonna (New York, Frick Collection). Mutual knowledge of sources could mean a similar period of work. That Hands H, I, and J based some of their miniatures on Eyckian models implies that their images postdate ca. 1435, when enough of Jan van Eyck’s art would have become available.67 These groups worked simultaneously, not several years apart. Scholars variously give Turin fol. 77v to Hands H, I, J, and, tentatively, to the young Barthélemy d’Eyck. Several other pages were painted by more than one master (such as Milan fols. 30v and 106), so it is reasonable to think that the G through K groups were contemporaries.

If Hands F through K painted in a single program in the late 1440s or later, it solves the fourth puzzle, which has to do with the subjects shown. The program of illustration was prepared by an adviser who was familiar with the Speculum humanae salvationis. Typological correspondences between the main miniatures and the bas-de-pages appear in the works of Groups F and H through K. A French translation of the Speculum prepared for Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy by Jean Miélot in 1446.68 would have been one convenient source for typological imagery, although the text was known earlier in other languages.69 Sermons and sources such as the Biblia pauperum, and the Rota in medio rotae alsooffered material for typological presentations.

The spaces available for illustration did not always demand the specific scenes that we see.70 The images do not all follow common patterns of manuscript illustration. Using John the Baptist’s birth as the main miniature on Milan fol. 93v (fig. 2) would have challenged an artist because the Baptist’s birth scene is not known earlier in large miniatures in Northern manuscripts. Hand G, who therefore had to invent the scene, had difficulty representing it logically; one may conclude that he did not suggest the subject.71 Someone had to suggest the subject of the Cavalcade on the Seashore miniature (fig. 1), which the artist could not make intelligible to us today. Someone had to approve the seated Virgin among standing virgins, another new subject for the Low Countries. Not all artists were sufficiently educated to decide upon the typological parallels or the hierarchy of scenes to be placed in the large miniatures, initials, and bas-de-pages. An adviser conceived the subjects, which required religious knowledge beyond that of the lay owner.

The list of subjects must have been known simultaneously to all artists (F through K), since it was followed by each group despite differences in style. One reason for thinking that Hand G’s work preceded that of Hands H through K, is that Hand G’s pages show no typological symbolism in the initials and bas-de-pages, although this symbolism appears in some works by the F and H through K artists. But the inventor of the illustrative program did not require it in all the initials or on the pages showing Saint Thomas Aquinas (Turin fol. 73v), Christ Blessing (Turin fol. 75v), the prayer of the French king (Turin fol. 77v), and others. Because of an artist’s superior talent, prestigious models, or the need for speedy execution, the program adviser sometimes approved an inconsistent treatment of subjects, as in the Arrest of Christ on Turin fol. 24, usually attributed to Hand G, that opens the Passion cycle in which the other pages show typological symbolism (fig. 17).

A single program of work also solves the fifth puzzle: why would several successive owners have bought and then sold only partially illustrated unbound leaves, having ordered just a few new images during each term of ownership and having left others blank even in the same quire? Not all the supposedly earlier pages are thematically significant enough to have warranted early painting, although König and others tried to discern the importance of the text passages and their position in the book.72 A single campaign accords with the usual practice described by Christopher de Hamel: “Gatherings could be distributed among several craftsmen working simultaneously . . . not even in order.”73 This leads directly to the sixth puzzle, the lack of tarnish in the metallic accents of the Turin portion, which led Hulin to suggest that it was seldom handled. Had there been several painting campaigns, the pages would more often have been opened and moved around. The final product, moreover, need not have been intended for daily use; I suspect that the manuscript was primarily an objet de luxe, possibly prepared for a special occasion in the life of a young male owner.

The reconstructed quires in the Turin portion show that few pages had images on both recto and verso, and few were painted on the same side of the bifolium before it was cut and bound. Those with paintings on the same side are fols. 59r and 60v, attributed often to G and H, and fol. 42r and Louvre 2025 (originally a verso), painted by the Llangattock (van Amerongen) artist in the K group. Of the bifolia painted on both recto and verso, the Turin portion had fols. 57 and Louvre 2023, the same artists having worked on both sides (also fol. 59 if G painted both sides of it, which is not certain; 60v is given to Hand H). Assigning an entire bifolium to a given atelier distributes the work logically.74 But other leaves show several hands and a given quire was not completed by one artist or group. It is therefore possible that sheets were spread out in several small nearby workshops at the same time. That explains some of the difficulty in separating individual hands. Even if artists in the K group came somewhat later to the enterprise, they could have been part of the same pictorial campaign. But as the K artists predominate in the parts of the Turin portion that precede the prayers in the Milan portion, they were employed from the start if work was handed around as it usually is, from the beginning of the text.

In the bifolium including Milan 93v and 100v, both images were begun earlier, as underdrawings show. Hand G finished only 93v in this bifolium. Fol. 97 is by an artist of the K group. This suggests the confiding of a single quire to artists working simultaneously. The quire with fols. 109 to 116 is more heterogeneous, including work by at least three different artists—one or more K artists, including the Llangattock Master, and Hand G on fol. 116 (see fig. 4). The final quire is also heterogeneous, containing images begun early on fols. 120 and 122, the True Cross picture often associated with G on fol. 118 (fig. 18), and work by the K group or the Llangattock Master on fol. 124. It makes sense to see the bifolia needing completion being assigned to contemporaries. A procedure for assigning miscellaneous pages to artists in multiple campaigns is difficult to imagine.

The miniatures are not all framed identically. Frames surround the miniatures on BNF n. a. lat. 3093, pp. 162 (fig. 19), 225 and 240, Turin fols. 24v, 73v, and 75v; and Milan fols. 14, 38v, 97, 111, 113, and 116 (see. fig. 4). The frames on Paris pp. 203 and 216, Louvre RF 2025 (fig. 20); Turin fol. 55v, and Milan fols. 94v, 93v (see. fig. 3), and 118 (see fig. 18) may have been widened slightly. Frames recalling those of the preceding century are on Turin fol. 49v and Milan fols. 30v (fig. 21), 106, 120, and 122. The frames were designed according to no order discernible today. There seems also to be no order to the bas-de-pages’ skies—unpainted, blue with or without clouds, or pale with flying birds. The lack of tight control or uniformity suggests haste in finishing the painting.

The working procedure was probably determined in part by the presence of images on several pages dating from the campaign of ca. 1400-10. Some were left alone (such as Turin fols. 39v, Louvre RF 2024, the main miniature on fol. 78v, and Milan fols. 4v and 87). Eberhard König remarked on the overpainting of other pages.75 Milan fol. 77v (fig. 22) shows a heavy-set Magdalen in the initial’s Noli me tangere scene who is physically unlike the three Marys, the angel, or the bas-de-page figures, but Jesus is rendered with the proportions, delineation, and lively brushwork of the boatman and Jonah in the bas-de-page. The figures of Jesus in the bas-de-page on Milan fols. 111 and 122 are identical, but the figure on the former is attributed by Buren and König to the Llangattock Master in Group K, and there is uncertainty about the artist of the bas-de-page on Milan fol. 122.76 The similarities among parts of various images suggest that the miniaturists knew each other’s sources and each other’s work, and that they painted simultaneously or nearly so.

The page attributed to Petrus Christus (see fig. 8) might also fit into this single campaign of work. Maryan Ainsworth and Maximiliaan Martens described Petrus Christus as using “significant borrowings” from manuscript compositions and motifs “showing his intimate knowledge of the art form.” They traced to manuscript painting Petrus Christus’s interest in “the development of a rational perspective” that affects the “relationship between image and viewer.”77 Panel painters and miniaturists, sometimes the same people, reused existing compositions.78 Ainsworth and Martens found that the “close study of the small-scale paintings [by Christus] reveals a remarkable resemblance to the technique and handling of manuscript painting.” Ainsworth emphasized the similar types of brushstrokes used and observed that in his small pictures, Christus used little or no underdrawing, as did many manuscript painters. She observed black contour lines at the edges of the forms in both Christus’s work and the Trinity composition on RF 2025.79

Hand G seems to have been in Christus’s vicinity, where borrowings from Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Robert Campin are evident. The upper right portion of the diptych showing the Crucifixion and Last Judgment at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has also been seen as a miniaturist’s work.80 Dominique Vanwijnsberghe identified a manuscript frontispiece in which the artist used a painter’s technique and affirmed that Campin and other artists in Tournai practiced both panel and miniature painting.81 At mid-century, so did Simon Marmion. That we cannot find G’s hand in other manuscripts could be due to his early death or to the well-known loss of many works of art from this region and time.

The K group artists responsible for Turin fols. 42 and 43 and Milan fol. 111, eager to paint deep spaces, saw similar spatial constructions in works by Rogier and Christus. The manuscript’s more rigid drapery and figural types are unlike those of Christus, suggesting that these artists were not his colleagues but only familiar with his work. The growing prestige of panel paintings around mid-century affected the taste for imitating large-scale works in this manuscript. This relates to the patronage of rich burgesses, clergymen, and some noblemen.

The young patron of the Turin-Milan Hours came from a family bearing arms, but not one conspicuous enough to have its heraldry recorded in sources known today. He appears at least five times.82 His willingness to obtain a partly finished older manuscript could reflect the prestige attached to its possible former possession by the Duke of Berry. Moreover, even as a manuscript fragment, the pages offered handsome writing, delicate borders, and several refined existing images.

I refer to only one patron. Although his cheeks look rounder in the Turin initials and his clothing changed from red and blue to gold on a dark tone in the final miniature in Milan (fol. 124, see fig. 10), the owner is consistently shown as a slender young man with a short haircut. There is no compelling reason for thinking that two young men of similar appearance, apparently still bachelors, owned the manuscript at different times, especially as clergy and women were the principal patrons for devotional manuscripts. Differences in the patron’s appearance could result if more than one artist painted the initials, the bas-de-page, and the miniatures in Turin showing the patron at prayer. The manuscript’s artistic supervisor specified the subjects with the patron’s approval and let the artists decide how to depict them.

***

I hope to have shown that the Turin calendar was created at the start of work on the original Turin-Milan Hours and that Duke John of Bavaria’s inability to claim Hainaut legally nullifies the historical claim for connecting Turin fol. 59v and Milan fol. 93v to Jan van Eyck, who in 1422–24 was working as that duke’s varlet de chambre. The presence of potentially more revealing heraldry on Milan fol. 93v, and the likelihood that Hand G worked in the 1440s or early 1450s free us from having to connect the work of Hand G to Jan van Eyck. This, coupled with the customary procedures for making manuscripts, supports the proposal that Hands F through K worked in one campaign.