In 1631 Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange and stadhouder of the United Provinces, became involved with an urban planning project for The Hague which survives in a series of twelve drawings today in the Nationaal Archief. The drawings tell an intriguing story of negotiation, deal-making, and the exertion of power at the center of the city. They also illustrate how the fabric of The Hague’s urban center became a locus for conflicting visions of what the city should be. The eventual implementation of a design based on the Prince’s principles provides insight into his visual and aesthetic ideas as well as his political vision.

In 1631 Frederik Hendrik (1584–1647), Prince of Orange and stadhouder (governor) of the United Provinces, became involved with an ambitious scheme to rework the central administrative district of The Hague. This urban-planning project is recorded in a series of twelve drawings which are today in the Nationaal Archief in The Hague.1 As site plans, the drawings provide a case study in the fraught territory of city planning. They tell an intriguing story of negotiation, of deal making, and of the exertion of power at the center of the city and at a pivotal moment in Dutch political history. They also illustrate how the fabric of The Hague’s urban center became a locus for conflicting visions of what the city should be. The divergent goals of both the States representatives and the stadhouder are revealed within the plans. The eventual implementation of a design tailored to the desires of the prince provides insight into his visual and aesthetic principles as well as his political vision. Attending to the role of Prince Frederik Hendrik in this debate illuminates the political implications of urban planning in the Dutch Republic.2

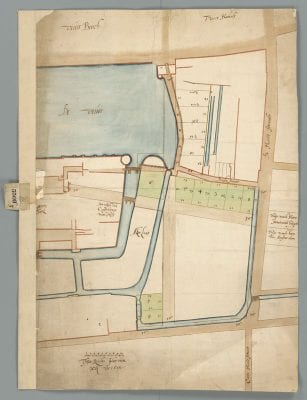

The twelve site plans concerning the redesign of The Hague Plein can be dated to 1632–34. As a group, the plans detail a variety of ideas and options regarding the rearrangement, subdivision, and use of the open space situated directly to the east of the Binnenhof (the governmental complex at the heart of The Hague) (fig. 1). This area had long held the Stadhouderstuin, the stadhouder’s private (but little used) pleasure garden. Bounded on all sides by a small canal and accessible by footbridges, the original garden contained paths, hedges, arbors, and small groves of trees. Directly west of the Stadhouderstuin, between it and the Binnenhof, was the Akerland, a long, L-shaped piece of land, also demarcated by canals. In 1631 the States of Friesland and Holland took up consideration of a proposal to subdivide the Stadhouderstuin and sell the resulting lots for housing.3 The motivations were financial and self-serving. A resolution dated December 14, 1631, established a subcommittee to explore ways to obtain “het meeste profijt” (referring to both financial outcome and overall worth), as well as to serve the “honor” of the land and provide improved accommodations for the States representatives.4 As stadhouder, however, Frederik Hendrik had a say in the disposal of this land, and he also had an opinion about how to express the “honor” of the city in visual terms. In January 1632 Frederik Hendrik protested against the planned subdivision. By summer, the States had ceded control of the project, adopting new resolutions in June 1632 that authorized the subcommittee to finalize the plans in conjunction with Frederik Hendrik.5 Frederik Hendrik’s opinion and approval (“goed vinden”) thus became essential to the project, and the move to a grander and more open design in the later drawings can be attributed to the prince’s direct intervention in the process.

The plans are large in format, colored with wash, and consistently labeled, as befits presentation drawings. Establishing a sequential dating of the individual plans is difficult;6 here, I group the plans into two sets, which match the two administrative stages of the project. The first set contains five plans (3306, 3308C, 3307A, 3307B, and 3307C) focused on the subdivision of the Plein proper. Each of the plans in this set provides a different option for the layout of parcels of land, streets, and access. The plans represent the States’ initial intentions to maximize profit while also providing civic improvements and new official accommodations. The second set contains seven plans (3309A/B, 3308E, 3305, 3308D, 3308A, and 3308B) that work out six different ideas for the Plein, as well as for the tract of land occupied by the St. Sebastiansdoelen, situated directly to the north along the east side of the Vijver lake. In these drawings, Frederik Hendrik’s ideas about visual dignity and a grand urban morphology are evident, as is his concept of a public urban experience within the republic of the United Provinces.

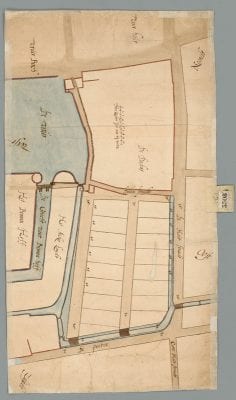

The first set of drawings, focused on the subdivision of the Plein itself, provides insight into the States’ goals and aspirations for the project. Plan 3308C (fig. 2) shows the existing layout of the area, as well as the simplest and most direct solution to the task of subdividing the Plein. The designer, probably the Hague surveyor Floris Jacobsz. van der Salm, has parceled the former garden into two city blocks and added a new street running between them.7 Sixteen full plots (and one partial) are inscribed into the space. Expanding the canals to the south (along the street known as de Pooten) and to the west (along the Akerland) and building new bridges would allow for improved transportation of goods and people in the area. Along the Houtstraat, to the west, the plans call for the canal to be filled in to make room for bigger housing plots.

In his manuscript Domus, Constantijn Huygens recorded the prince’s (and his own) distress upon looking at this plan.8 The design does meet the need for salable plots and it does create potential sites for government representatives to occupy: both were central needs expressed by the States. It also improves access by water to the areas to the south and west of the Binnenhof. But it permanently gives up the open spaces of the Plein and the visual possibilities of that square. The plans in this group are concerned only with manipulating the size, spacing, and regularity of the plots on the Plein (to a maximum of twenty-six salable plots) (fig. 3). As the drawings organize and rationalize the Plein along commercial lines, focusing on the efficient use of space for housing and transport, they also capture the resolutely practical orientation of the States’ agenda. Huygens noted that the parcels were divided “met inhalige hand,” thus identifying financial gain as the motivating force.9 From the prince’s perspective, such an approach was a failure. Without an increase in visual dignity or grandeur, the plans for a renovated Plein did not increase the “honor” of the city or embellish it in any way. Frederik Hendrik’s rejection of the plans was definitive: he declared the initial subdivision an “outrageous crime” that would “deform” The Hague for future generations.10 Huygens commended his “invincible prince” Frederik Hendrik for standing by his vision of a generous open space in the city center instead of the States’ alternative, subdivision into small parcels that Huygens scornfully described as diminutive “mouseholes.”11

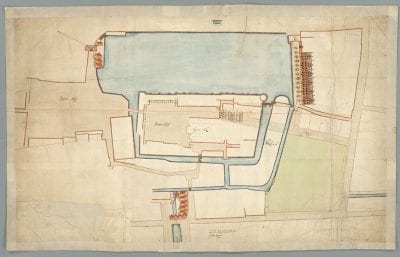

The second set of drawings presents an entirely different vision of the city’s center, one closer to the prince’s ideas. The ideal layout of the Plein and its surroundings that appears in these seven plans is steeped in classical thinking, conveying concerns for axiality, uniformity, and aesthetics which are clearly connected to the prince’s own experience, learning, and values. Thus this set appears to have been completed after June 1632, when the States gave Frederik Hendrik the deciding say on the project.12 The project now encompasses the larger context of the Binnenhof, including the Plein, the St. Sebastiansdoelen lands to the north (which were then occupied by guild’s shooting range), the Akerland, and the Vijver itself. An overview plan of the site, 3309B (fig. 4), provides the conceptual blueprint for the second stage of the project.13 With only eleven parcels for houses (five in the northern part of the Plein and six along the Vijver), this plan abandons the goal of mass subdivision in favor of aesthetic outcomes, such as openness, regularity, and visual dignity.

An intriguing feature of 3309B is the thin red line inscribed across the axis of the Binnenhof, stretching from the Buitenhof all the way across the Binnenhof to the Houtstraat. The line, clearly drawn with a straight edge, makes no concessions to the vagaries of the elements it intersects, whether the bridge on an angle or the sloping canals, or even obstructing buildings. The line is a conceptual device that illustrates a new philosophy: it shows that axiality mattered as a means both of organizing access and egress and of providing linkages between the spaces of the city center. Such an axis connects to new morphologies that were developing in many of the grand cities in Europe during the seventeenth century, which the prince knew from his youthful travels to France, England, and Germany.14

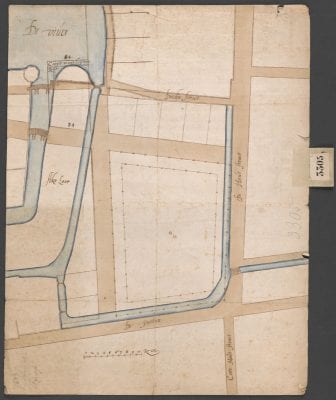

The remaining plans register the struggle to reconcile the conceptual ideal of axial relationships with the reality of the existing structures. One compromise adopted is a broad new avenue between the Binnenhof and the Houtstraat. The new avenue is drawn at the expense not only of part of the Akerland but also of several existing structures within the Binnenhof (a washhouse, a peat shed, and part of the old kitchen gardens). It replaces the old narrow, twisting passageways into the Binnenhof with a broad and open passageway, complete with new and bigger bridges over the Akerland canals (see Plan 3305, fig. 5). Huygens recorded the prince’s support for a similar broad avenue along the Vijver and the west side of the Plein (visible in fig. 5), which Huygens says he and the prince laid out together.15 Throughout this plan, roads and waterways have been straightened, corners given rectilinear shape, and roads broadened, providing uniformity, regularity, and visual access throughout the city center.

Similar concerns for regularity are visible in the concept drawing 3309B (fig. 4). Here, along the Vijver, van der Salm has sketched six proposed houses with matching symmetrical facades and stepped gables, fronted by a broad tree-lined avenue. There is a pronounced contrast between these stately residences along regular and generous boulevards and the small, jumbled houses precariously sketched in on the other side of the Vijver. Even the lake has been regularized, its uneven eastern bank rigidly straightened to make room for the frontage road. This plan calls for major alterations to the fabric of the city, including the filling in of a substantial chunk of the lake, the closure of the ring canals around the Plein and the Akerland, the straightening of the Doelenstraat, and the regularizing of the rounded end of the Akerland into a rectilinear shape. With the cooperation of the guild of St. Sebastian, Frederik Hendrik’s requirements were executed in the final plan (3308B), despite the scale and expense of the engineering commitments involved with these alternations (fig. 6).16

Plan 3305 and Plan 3308B, the final version, share the prince’s vision of the Plein as an open area. In 3305, the space is made ceremonial by the addition of a set of a double colonnades or bollards. In 3308B, green wash highlights the new housing plots to the north and southwest of the Plein, where they make up an imposing block. Similarly, five plots along the Vijver share an axis as well as a presumably uniform treatment. The addition of three new plots on the Akerland (numbers 6, 7, 8) not only adds more salable properties but also allows for these grand residences to encircle the Plein, with the existing dignified townhomes on the east side completing the monumental framing of the open space.17

In both scale and exposure, these were significant properties. The plots sold quickly, during March 1633, for between 2,810 and 3,550 pounds, despite a set of restrictions applied to all owners.18 These included an agreement that only single family homes would be built, that the buildings would be completed within two years, that owners would cover the cost of improvements to the Plein (including filling in the encircling sloot and leveling the ground), and that they would never dump household waste on the Plein or the Doelenstraat.19

The new owners of these residences represented a mix of society in The Hague, including aristocrats such as Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen (plot no. 6, for 3,550 pounds; this is the site of the Mauritshuis today) and locals such as Gerrit van Druvesteijn (plot no. 5, 3,550 pounds) and Wijer Gerrits Overmeer (plot no. 3, 2,810 pounds).20 Plan 3308B shows that two properties were set aside for governmental administrators on the east side of the Houtstraat. The northern of the two plots is marked “thuijs vande Heere Secretaris Huygens.” The southern space, marked “Thuis van de heere van Amsterdam,” was designated for the Amsterdam representatives, thereby fulfilling one of the original goals of the project. However, in March 1634 Frederik Hendrik departed from this plan, and gave both plots 7 and 8, prime pieces of real estate, to his secretary Constantijn Huygens. The gift shows that the prince’s reach extended well into the execution of the project; not only did he have the initial right of approval of the plans themselves, but he also selected his closest allies to occupy the most visually crucial spaces. With the prince’s encouragement, Huygens built on that site a house renowned for its strict application of classical principles.21 Frederik Hendrik consulted with Huygens on the design of his house, and letters and accounts show that he visited the Plein building sites frequently in person during construction; in many instances, Huygens wrote of his conversations about architecture with the prince, whom he considered to be an authority on the subject.22 Like Huygens, and court-affiliated architects Jacob van Campen and Pieter Post, the prince was educated in the ideas about classical architecture currently circulating in treatises by Sebastiano Serlio and Vincenzo Scamozzi; these styles appear in many of the prince’s other buildings.23 The Plein thus carries the visual “brand” of the prince, while housing his supporters and presenting his ideas about the nature of the city.

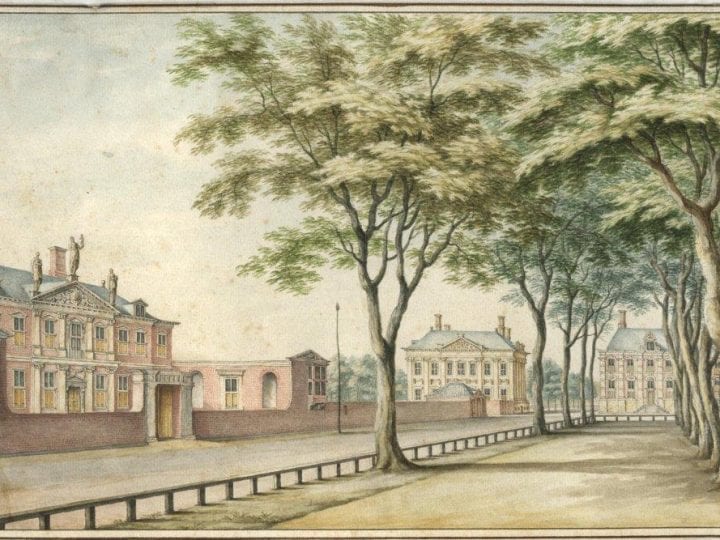

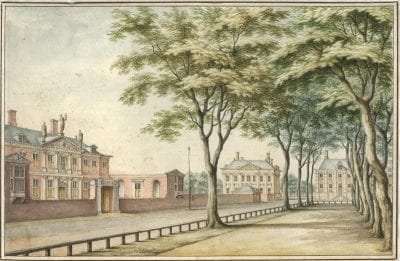

A drawing of ca. 1690 (fig. 7) shows the final result of the prince’s plans and supports Huygens’s enthusiastic description of the new Plein as a green, spacious, and “regulated” space with pleasant views.24 Although it provides only a partial view, the drawing captures the effect of the Plein as an urban oasis. It is a leafy, verdant park, surrounded by a generous avenue and flanked by a stately procession of grand mansions. The houses do provide an impressive frame for the new park, with Huygens’s house (at left) and Johan Maurits’s urban palace (built by Jacob van Campen) setting a high standard of classical magnificence. As Huygens wrote: “I ask myself, if there is a more elegant, distinguished, and stately sight in the world.”25

The prince’s agenda for this unusual space derived from his experiences as a young man at the court of King Henri IV of France, his godfather. Frederik Hendrik spent almost a year, between 1598 and 1599, in Paris, and made further trips in 1610–11. He would have witnessed firsthand Henri’s architectural ambitions in the rebuilding of the Louvre, his remodelings at Fountainebleau, and the planning of the Place Royale (fig. 8).26 Begun in 1605, the Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges) was the first planned square in Paris. Hilary Ballon has shown how the Place Royale drew together disparate social and economic needs into a unified urban space supported by and overseen by the king himself.27 Combining industry (in the form of ateliers and factories for silk production) with commercial activity (in the form of shops on the ground floor) and residential needs (in the form of houses for both nobles and bourgeois above) within an enclosed space marked by symmetrical architecture, the Place des Vosges acted as a grand experiment in urban and civic planning.28 Of course, Frederik Hendrik did not enjoy the same monarchical power as Henri IV; however, the correspondences between the two projects suggest that Frederik Hendrik deployed similar ideas about architecture as a shaper of urban identity at The Hague Plein. Like his godfather, Frederik Hendrik was an active and engaged patron of architecture. As discussed above, contemporary evidence, such as Huygens’s account of the project, reveals that Frederik Hendrik was a hands-on patron with a specific vision for the redevelopment of the Plein.

The concepts expressed in the plans suggest a flexible view of society that navigates between the republican principles of the Dutch nation and the institutional vagaries encoded into its structure. William Temple characterized that structure as having the following components: “The main ingredients [which have gone] into the Composition of the State, are the Freedom of the Cities, the Sovereignty of the Provinces, the Agreements or Constitutions of the Union, and the Authority of the Princes of Orange.”29 The “mixed” government of the United Provinces contained structures that drew from monarchical systems (the stadhoudership itself), republics (the system of representation on the provincial and federal levels) and democracies (the principle of election).30 Frederik Hendrik’s own anomalous position as both elected servant and, for outsiders at least, de facto leader of the nation is a microcosm of the competing elements contained within the Dutch republic.

A similarly nuanced view of social and political reality is evident in the plan for the Plein. The spaces of the new Plein do not cordon off the court or the government from the people. In fact, by leaving the square open and accessible, the Plein reintroduces public space for citizens at the heart of the governmental area and organizes appropriate venues for the various components of a republican system. The avenues, bridges, and plots of land occupy visually accessible and spatially logical positions that clarify the relationships between the court and the government, the courtiers and the burghers, and the people and the city. Unlike the explicitly commercial agenda that motivated King Henri’s Place Royale (and the States’ design for the Plein), Frederik Hendrik’s design registers instead a concern for access (both visual and physical), for uniformity, and for regularity. Citizens could linger in the park or walk unobstructed through the Binnenhof spaces, all the while rubbing shoulders with members of the court and elected representatives from across the United Provinces. In his political career, Frederik Hendrik accomplished a similar feat.

As a politician, Frederik Hendrik was known as a moderate who navigated between polarizing positions with consummate skill. In the early 1630s he was managing problems with individual cities and the States General, undertaking negotiations with the provinces for the stadhoudership of Friesland, executing the sieges of Maastricht and Ghent, and agitating for reunification of the North and South Netherlands, all while working with the government of France on an alliance during the long-running war with Spain and preparing for an eventual peace.31 Although historians have long debated the prince’s own desires regarding assuming the role of Count of Holland (and thus becoming a hereditary ruler), in his public actions the prince remained committed to the principles of republicanism, however irritating, inefficient, and cumbersome they often were.32 Indeed, the balance between the power of the stadhouder and that of the burghers was a central factor in the political functioning of the United Provinces; Frederik Hendrik’s ability to maintain, even promote, that balance becomes clear upon considering the less moderate stadhoudership of his son, Willem II.33

Frederik Hendrik’s plans for the remodeling of The Hague Plein manifest republican principles in design. The plans reframed a formerly restricted princely space as a venue for celebration of The Hague’s elite classes – while also offering pedestrians from lower social classes the chance to partake in the increased visual dignity and magnificence of the city center. For observers and visitors from abroad, the new Plein also made a visual case for the importance of The Hague, which not only contained the residences of the Prince of Orange and his court but also represented the authority and identity of the new republic. As these plans attest, in the 1630s The Hague was no longer a provincial outpost. It now boasted a civic, residential, and governmental center that architecturally rivaled others in Europe, reflecting the growing stature of the United Provinces. The principles of this upstart nation could be witnessed in the very fabric of the Plein. Similarly, the changes of design shown in the plans testify to the connections between urban planning and political process. The Plein designs capture in visual form the sometimes opposed ideas of the prince and the States’ representatives. In the end, Prince Frederik Hendrik’s innovative design for The Hague’s city center codified the delicate political balance between the Dutch court, the government, and citizens. The history of these designs also bears witness to the prince’s recognition of the power of the visual environment he occupied.