Just after his arrival in Amsterdam, Lairesse painted an impressive series of six paintings on the infancy of Jesus. This article argues that the series must have been made for the Catholic South, presumably for an ecclesiastical institute in Liège or vicinity. Its character connects his painted cycle with the Counter-Reformation. Lairesse involves the viewer closely with the religious content, encouraging meditation, contemplation, and reflection. Despite his flight to Protestant Amsterdam, and his joining (as a full member) the Francophone Walloon Reformed Church, Lairesse continued to maintain warm links with the highest circles in his native Liège. In the Infancy of Jesus, Lairesse thoroughly studied the engravings of Goltzius’s Life of Mary (as well as Rubens and Rembrandt). He always added grace, idealism, and decorum to a setting and composition that he himself described as “genuinely Antique.”

Introduction

The name Gerard de Lairesse prompts art historians to think primarily of cabinet pictures, ceilings, and chamber paintings, with subjects from classical mythology, Greek and Roman history, pastoral literature, or complicated allegories. Until Lairesse arrived in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, religious subjects were the mainstay of the output of successful history painters, but they are in the minority in Lairesse’s oeuvre. Moreover, a considerable proportion of his paintings with religious themes were destined for customers in Liège, the main city in the Prince-Bishopric of the same name, where he had been born and educated.

In addition to a few large altarpieces, which he painted, both before and after his arrival in Amsterdam, for churches and monasteries in Liège and the surrounding area, the most exceptional work is a series of six paintings depicting scenes from the infancy of Jesus. Lairesse preferred to select fairly unusual subjects for his paintings and he encouraged his fellow artists to do the same in his Groot Schilderboek.1 For these works, though, he had to delve into conventional biblical themes. Studying prints was an essential part of this. Lairesse was, however, fervently against recognizably borrowing compositions and motifs, lashing out against some of his colleagues who “rarely do anything that has not been taken in its entirety from the prints or drawings of others.” As he put it, “taking an arm from one, a leg from another, a face here, an item of clothing there, the body from another, and thus patching together their entire composition.”2

Studying the Infancy cycle offers an opportunity to examine how Lairesse handled biblical subjects that had a long pictorial and iconographic tradition. Was he able to withstand the temptation of “misusing” prints in the way he described? After a brief summary of Lairesse’s religious work in the context of his faith, the focus will be on an analysis of the six paintings with scenes from the infancy of Jesus.

A Change of Culture and Faith: From Liège to Amsterdam

In Liège, which was not only Lairesse’s birthplace but also the city where he achieved his first successes, the Catholic Church was omnipresent. Painting had to spread the message of the Catholic faith. Seventeenth-century Liège was just as Catholic as Antwerp, but in terms of politics, government, and cultural orientation, there was no comparison. In Antwerp, Rubens, his pupils, and their followers had a central place in Counter-Reformation painting. Rubens was capable of steering the old iconographic traditions in the direction set by the new ideological thinking. In contrast to Antwerp, where Catholic reconstruction had been diligently undertaken from 1585 onward, the iconoclastic fury and the Reformation had bypassed the Prince-Bishopric of Liège. As part of the Holy Roman Empire, it was not involved in the Eighty Years’ War, although it did suffer in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48): Liège was besieged and severely plundered in 1636.3

Art in Liège was strongly oriented toward Rome thanks to the influential figure of Bertholet Flémal (1614–1675).4 Flémal was a pupil of Gérard Douffet, who had trained in Rome, and he also spent his formative years in Rome, where he was greatly impressed by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). Once back in Liège, Flémal became the Prince-Bishop’s court painter. His work helped shape Lairesse’s education as a painter.

In April 1664, when he was twenty-five, Gerard de Lairesse’s life was turned completely upside-down by a stabbing. To escape prosecution, he had to flee with his beloved Maria Salme. During that flight, they were married, soldier-style (à la soldatesque) in the Spanish fortress of Navagne, on the border with the Dutch Republic.5 In April 1665, they had their first-born son baptized in a Catholic house-church in Utrecht.6 Moving to the Republic meant adapting to a society where Protestantism and burgher merchants held sway, not to mention a different language, culture, and religious practice.7 The Catholic Church was merely tolerated there. Its places of worship had been confiscated and the episcopal hierarchy had disappeared. Mass was held in house-churches. The Dutch Republic had become a missionary country as far as Rome was concerned, in which the successful Catholic Counter-Reformation was only slowly making headway.

The move from Utrecht to Amsterdam was then followed by a striking step: in August 1666, the couple became full members (lidmaten) of a Francophone church, the Walloon Reformed Church. It is difficult to say whether they chose the church for pragmatic reasons or whether they already felt drawn to the Reformed faith.8 Becoming members meant that the couple placed themselves under the authority of the church council and its strict discipline. Full members were a minority inside the Reformed Church. The majority chose the role of sympathizers (liefhebbers). They attended the services but could not participate in the Lord’s Supper.

If it was the hope of commissions in particular that drew the ambitious emigrant to the Republic, his expectations were indeed fulfilled. Lairesse had plenty of work in Amsterdam and was soon in great demand as a versatile and celebrated artist. That success encouraged him to let his brothers, who also painted, share in his good fortune and bring them into his studio. Jacques (1643–1690) and Jan Gerard (1645–1724) both moved to Amsterdam in 1676. It is noteworthy that they, too, in 1677 chose to join the Reformed Church. Their mother, who relocated with them, was registered as a member in 1676.9

Gerard’s relationship with Catholicism was becoming awkward throughout his years in Amsterdam. This can be concluded from his refusal to give his consent for his son Johannes to marry a Catholic, Cornelia van Westhaven. As well, Gerard was absent from the betrothal (ondertrouw) of his son Abraham to Johanna van Beveren (presumed to have been Catholic).10 He did not, however, let his private feelings guide his choice of clients. He continued to produce altarpieces; it is remarkable that—as far as we are aware—these were not intended for house-churches in the Northern Netherlands but were exclusively commissions from his native region.11 Lairesse did paint a double set of organ shutters for the Reformed Westerkerk church, though.12

Lairesse’s Religious Works

Roughly 15 percent of Lairesse’s surviving oeuvre of over two hundred and forty historical pieces are religious in nature: there are thirteen compositions from the Old Testament, seventeen from the New Testament, and seven religious works representing saints and church fathers. This does not include engravings and drawings.13 This output of religious paintings can be further subdivided into ecclesiastical commissions and works that were primarily destined for private homes.

The earliest of the seven altarpieces dates from 1660. That was the year when Lairesse left Liège in order to paint a Martyrdom of Saint Ursula for the St. Ursula Church in Aachen.14 Around 1663, he produced a Coronation of Mary for the church at Aywaille.15 During the same period, Lairesse was commissioned by the Ursuline convent in Liège to paint the Conversion of Saint Augustine and the Baptism of Saint Augustine.16 While in Amsterdam, he completed a prestigious commission in 1687 for the main altar of the cathedral at Liège with an Assumption of Mary.17 His finest altarpiece, a Transfiguration, dates from the same period, along with a Crucifixion that was probably made for the same—unknown—church.18 A smaller-format Crucifixion and an Ecce Homo may also have served as altarpieces or devotional works.19 His Saint Cecilia and a clearly Counter-Reformation painting such as Saint Theresa in Ecstasy were also probably made for ecclesiastical settings.20

A religious piece from his time in Liège that will more likely have been made for a private home is an unusual depiction of John the Baptist (fig. 1). The strikingly naturalistic way in which the body is represented makes it look like an academic study of a posed nude model that was then transformed into a figure of John the Baptist. A more difficult item to explain is the addition of a relief showing a struggling young boy who is being circumcised; a unique composition as far as is known.21

Belgium, Fondation Albert Vandervelden (artwork in the public domain) [side-by-side viewer]

The Noli me tangere dated to 1675, the Holy Family, the Old Testament Jael and the tondo with Judith painted in around 1687 were almost certainly for private homes.22 The last of these paintings, a commission from the mayor of Liège, shows the warm links that Lairesse continued to maintain with the highest circles in his native city. Another example is the recently discovered Anointing of Solomon, which most probably was made for the Prince-Bishop of Liège, Maximilian Henry of Bavaria (fig. 20 in the Sluijter essay in this compilation). An etching of it from 1668 is dedicated to this prince.23

The biblical pieces from his time in Amsterdam include a work (fig. 2) where the subject matter was probably chosen by Lairesse himself, not so much for its religious content but because he could then compete with his great example, Poussin (fig. 3).24 Through his Death of Ananias, Lairesse enters into dialogue with both Poussin and a famous invention by Raphael (fig. 4), both of which he must have known from prints (fig. 5). In the Ananias, he shows how he can stand out not only by the warm use of color and subtle shadows but also by the more viewer-oriented variety in movement and emotion.25

A number of works give a clear idea of the position Lairesse adopted in the religiously pluralistic city of Amsterdam. Lairesse stated in his Groot Schilderboek that he preferred depicting God in human form rather than as a symbol. Even so, he was careful about this from 1665 onward, undoubtedly because of the value placed on the second commandment in the Dutch Republic.26 For a painter, the human form is more of a challenge than the “soulless shape of the Triangle.” And as a former Catholic, he was familiar with “God the Father as a merciful old man.”27 Lairesse did not paint God often, though: God only features prominently on the altarpiece in Aywaille.28 But the drawing Baptism of Jesus and the etching after it made by Johannes Glauber (figs. 6–7) show that Lairesse was not dogmatic.29 In that drawing, Lairesse depicts God in human form whereas in the etching, God has disappeared. This illustrates that Lairesse adapted the Catholic iconography to take account of Protestant viewers. His pragmatic approach can also be seen in the final paragraph of his chapter on the portrayal of the Trinity: “But in all this, a Painter must act with moderation” and must “not misuse” his authority, granted by the Bible and the Church Fathers.30

This desire for moderation can also be seen in Abraham Entertaining the Angels (fig. 8).31 Genesis 18:1–2 states that “The Lord appeared to Abraham” in the form of “three men.”32 The visitors are usually represented as three angels or three men. Rembrandt and Aert de Gelder diverged from this, emphasizing a single individual within the group of three; in his etching of 1656, Rembrandt gave that figure various attributes of God, and Aert de Gelder copied this approach.33 By contrast, Lairesse shows them as three young men of equal status dressed in classical style, thereby avoiding any reference to God or the divine. The humble pose of Abraham, who is carrying a plate of food to the already richly laden table, emphasises the Old Testament hospitality that Calvin highlighted and focuses less on the divine promise of a son (Genesis 18:3–8). A painting such as this was therefore ideal for a client who wanted to stress his own hospitability in his reception room.

Infancy of Jesus

As stated above, the series of paintings on the infancy of Jesus has a special place within Lairesse’s oeuvre.34 This cycle consists of six large canvases, the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Circumcision, the Adoration of the Kings, and Simeon’s Song of Praise (figs. 9–14). The individual subjects may be thoroughly traditional, but a painted cycle is a great rarity. Series of prints are more common. The most famous is the six-print series by Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) from 1593–94, which was also known as the Life of Mary.35 This influential series of prints includes the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Circumcision, the Adoration of the Kings, and the Holy Family with John the Baptist (figs. 15–20). Thus five of the themes match those in the series by Lairesse. Mary is present in all pictures in both series and, as we will see, Lairesse had studied Goltzius’s prints carefully.

There is one painted series that Lairesse could have seen during his time in Amsterdam. It is thought that Hendrik Uylenburgh (1584/9–1661) possessed such a series in 1627, painted by his brother Rombout (1580/85–1627/28) using the grisaille technique.36 This series consists of the Visitation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Circumcision, the Adoration of the Kings, and Jesus Disputing in the Temple (figs. 21–25). The cycle, which owes a great deal to Goltzius, is thought to have been larger. Rembrandt in turn produced a series of six small etchings in 1654 with scenes from Christ’s infancy (figs. 26–31). Five of them are almost identical in size, but the Adoration of the Shepherds is somewhat larger.37 Rembrandt chose different subjects and extended the series further than Uylenburgh. In addition to Jesus Disputing in the Temple there is also the Holy Family Returning from the Temple. Of the six scenes, only two have the same subject matter as the paintings in the series by Lairesse (the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Kings) and they show no borrowings from Rembrandt’s etchings. The series by Goltzius, a Catholic, with their dedications to the Catholic Wilhelm V, duke of Bavaria, bear a clear Counter-Reformation stamp.38 This probably shows the context in which the cycle by Lairesse should be placed. More about that later.

Apart from the Uylenburgh series, I am not aware of any painted Northern Netherlandisch Infancy cycles, although there are some from the Southern Netherlands. An anonymous series that is currently in Saint Etienne comprises the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Presentation in the Temple, and Jesus Disputing in the Temple.39 A second series from the south, attributed to Artus Wolffort (1581–1641), contains the Visitation, the Circumcision, the Presentation in the Temple, and the Adoration of the Kings. It is not known whether this series always consisted of four compositions or whether two have been lost.40 A cycle attributed to Abraham Willemsen (1605/10–1672) also consists of four scenes: the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Circumcision, and the Presentation in the Temple.41 It is striking that almost all the various series from the Southern Netherlands and the one by Lairesse contain the Annunciation, the Visitation, and the Presentation in the Temple. Although none of these series has anything like the quality of Lairesse’s, they do suggest that the cycle by Lairesse must have been commissioned by someone in the south.

Originating from Huy?

Information about the provenance of Lairesse’s Infancy series is limited: it turned up in 1984 in a private collection in Portugal.42 One nineteenth-century source—an inventory of art stolen during the French occupation (1794–1815) and partly subsequently repatriated, recorded in 1883 but based on a lost list from 1815—mentions such a series by Lairesse in the collegiate church of Notre Dame in Huy, some thirty kilometers southwest of Liège.43 Although the Huy series was taken by the French, the same report states that it never reached Paris and there had been no trace of it ever since. This begs the question of whether the Huy series is the same as the Infancy series being discussed here. The report describes the series as follows: “Six large paintings presumably by Lairesse, representing the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, and probably the Presentation in the temple, the Flight into Egypt, and another, Mystery in the Annunciation: the Virgin is wearing a straw hat in the Visitation or the Flight into Egypt, she is represented bent and leaning on a stick; height 3 to 4 feet, over a width of 2 meters.”44 (Six grands tableaux présumés de Lairesse, représentant l’Annonciation, la Visitation, la Nativité, et probablement la Présentation au temple, la Fuite en Egypte, et un autre, Mystère dans l’Annonciation: la Vierge est couverte d’un chapeau de paille dans la Visitation ou la fuite en Egypte, elle est représentée courbée et appuyée sur un baton; hauteur 3,5 à 4 pieds, sur une largeur de deux mètres).

This report therefore indicates that this was a series of six paintings, four of them with the same subjects as the series discussed here. The fifth subject, the Flight into Egypt, is different and the sixth subject remains unnamed in the report (“et un autre, Mystère dans l’Annonciation”). I would argue that “Mystère dans l’Annonciation” is the term used for the entire cycle. After all, the Annunciation initiates the mystery of God’s incarnation.45 The specific descriptions of Mary’s straw hat, posture, and stick do not, however, match the current series, and the dimensions are different (some 105 to 120 x 200 cm, as opposed to 148 x 186 cm). Can these discrepancies be explained by the chaotic situation during the French occupation, when a French clerk drew up the lists that the author of the 1815 list used, someone who had never seen the paintings himself? What is crucial, in my opinion, is that a series of six large paintings depicting the Mystery of the Annunciation by Lairesse hung in the church at Huy. That theological description fits very neatly, at least with the start of the series we are discussing.46

Dating

The attribution of the series being discussed here is not disputed, although none of the paintings is signed or dated. Roy asserts that the religious iconography points to Lairesse’s period in Liège, whereas the style would indicate his early Amsterdam period. Roy places greater weight on the latter and dates the series to 1668–70. Because of the similarities to the Liège paintings, I would prefer to date them as originating in 1665–67.47 Similarities can be found to the above-mentioned Baptism of Saint Augustine of 1663: the architectural background resembles that in Simeon’s Song of Praise (see fig. 14) and the same also applies to the staircases and the figures in the Circumcision (see fig. 12) that are cut off mid-torso.

The Visitation (see fig. 10) has compositional elements that are similar to Thetis and Achilles from 1664–65, with sharp outlines, solid architecture, and dark colors.48 In terms of the coloring, the Annunciation (see fig. 9) bears a close resemblance to the altarpiece in Aywaille from ca. 1663. Lastly, the engaging children on the left in Simeon’s Song of Praise are akin to the ones in the Temple of Honor from 1665–68.49 In some parts, a foretaste can already be seen of a lighter and more airy palette, but there are still too few Amsterdam-style components present to date the series to ca. 1668–70. Dated works from that time, such as the Allegory on the Peace of Breda (1667; fig. 15 in the Sluijter essay in this compilation) and the Allegory of the Senses (1668; fig. 3 in Wenley essay in this compilation) already show a more emotional relationship between the figures and more convincing spatial qualities.50 Eric Jan Sluijter has demonstrated that stimulus from the art in Amsterdam was a defining factor for this stylistic period.51 The Infancy series has to be dated to just before that phase.

Annunciation

The series commences with the Annunciation (see fig. 9). Lairesse has painted Mary in the traditional humilitas pose, with her hair covered and her hands folded humbly.52 Lairesse seems to have derived the descending angel as a mirror image of the engraving by Francesco Villamena after Mario Arconio (fig. 32).53 We do not find in that engraving, however, the putti scattering flowers; albeit new to the Dutch Republic, they correspond to the tradition of the Southern Netherlands.54 Lairesse’s Mary follows the tradition of depicting her with arms crossed in front of her breast, signaling the words of consent marking the conception of Christ: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord: let it be to me according to your word.”55 The book Mary was reading—according to tradition, Isaiah’s prophecy of a virgin birth—sits on the lectern.56 The Annunciation initiates the mystery of the incarnation of Jesus, and is a subject that is not found in the series by Uylenburgh and Rembrandt. Subject matter that puts Mary in the center was clearly more appealing to Catholics than to Protestants.57

A few years later, Lairesse painted a second version of the Annunciation (fig. 33).58 The composition is a mirror image of the earlier version, but Mary’s attributes—the sewing basket and lectern with book, which seem to have Goltzius’s engraving as the source (see fig. 15)—are unchanged. They refer to her domestic work and her knowledge of the Old Testament. In the earlier painting, the light is shining from the left onto the floating angel, reflecting on the half-illuminated Mary; she is surrounded by darkness. In the later Annunciation, the divine light that enters the room with the Angel Gabriel and the Holy Spirit is shining fully on Mary and casting a striking shadow on the rear wall. The divine light, interpreted as the word of God, has already reached her. In this work, the many cherubs are subordinate to the majestic archangel, who is depicted as a true authority from heaven.59 Gabriel appears in a whirlwind of light, clouds, robes, and cherubs. The soft contours of the angel, the voluminous shapes, and the warmer colors add to the emotional relationship between the figures. Roy dates this version to 1668–70, which would seem to be correct. The convincing sense of depth and the unity of color and light are elements of Lairesse’s style that appear from 1667–68. The angel and in particular the billowing robes that have been captured in motion are reminiscent of the Amsterdam paintings from the 1660s by Adriaen van de Velde (1636–1672) and Karel Dujardin (1626–1687).

Visitation

In the Visitation, Zacharias is watching from his home as his pregnant wife Elizabeth and kinswoman Mary greet each other (see fig. 10). The meeting between Mary and Elizabeth is frequently shown taking place on a staircase, but Lairesse adds a variant to this by abruptly cutting the staircase off. As a result, the stairs largely belong to the visual space of the viewer as if he or she were climbing it, first past a conspicuously placed pumpkin that is undoubtedly a symbol of the new lives that Mary and Elizabeth are carrying. Elizabeth has descended toward the same level as Mary, though she is still a little higher up. Various representations of the Visitation seem to have different ideas about the relative positions of Mary and Elizabeth. In Dürer, Goltzius, Rubens, Lievens, and Rembrandt, Mary is looking down on Elizabeth. In contrast, Jordaens and Lairesse have Elizabeth above Mary, a striking choice given that Mary is more important in God’s holy plan.60 Elizabeth realizes this too: “Who am I, that the mother of my Lord should visit me?” (Luke 1:43–44). But Mary is humble, which could be the reason for showing her bowing more deeply. Lairesse also portrays Elizabeth as taller in his etching of the Visitation, but there he does so by placing Elizabeth one step higher (fig. 34).61 Mary almost kneeling and Elizabeth standing upright reflect the postures Goltzius used, although Lairesse has swapped them.

Lairesse is also responding here to Rembrandt’s Visitation of 1640 (fig. 35).62 He takes the diagonal defined by the figures—starting from Zacharias supported by a small boy in the door opening through to the raised area where Mary and Elizabeth are standing—in the same way Rembrandt did, but as a mirror image. In Rembrandt’s work, the head of the older Elizabeth is inclined toward Mary, whereas in the Lairesse, the younger figure bows to the older woman. The similarities in composition make the differences all the more obvious. Lairesse has contrasted his ideas on decorum and the importance of beauty with Rembrandt’s “from life” ideology. He has enhanced every element of the architecture, clothing, and figure types. Rembrandt depicted Mary in sombre green and brown shades; Lairesse portrayed her in red and blue, as was customary in the Catholic world. Lairesse left out the stick that Rembrandt used to show that Elizabeth was already elderly. In the Rembrandt painting, the somewhat scruffy small dog is barely responding to the visitors, but—like Goltzius—Lairesse includes a purebred dog springing up excitedly to greet Mary. Lairesse must also have recognized that Rembrandt’s figure of Joseph climbing the stairs was a reference to Goltzius’s engraving (see fig. 16). Following Rembrandt’s example, however, Lairesse turns Goltzius’s modest staircase into an important compositional element. His version also involves incorporating Joseph, a man shown in the prime of his life, into the scene more integrally than in the Goltzius. The emphatic reference to Rembrandt’s composition shows Lairesse was consciously emulating Rembrandt’s example in his new “antique” style.

Adoration of the Shepherds

In the Adoration of the Shepherds, Jesus is revealing himself to the Jewish people (see fig. 11). Lairesse has not represented elderly or rustic figures with weather-beaten faces, as would have been customary in the Netherlands. He wanted to portray decency, beauty, and grace, so he painted strikingly youthful women here. Goltzius placed two women in the background (see fig. 15); Lairesse has them at the front. He depicts elegant, excited young shepherdesses and a shepherd who delight in the birth.63 Unusually, Lairesse did not adhere to “antique” clothing for these shepherdesses, but instead dressed them in the customary pastoral apparel, with a bodice and skirt that are clearly idealized contemporary elements. The girl turning to face the viewer and bringing a lamb as a gift—a motif that refers to Jesus, who will die as the Lamb of God so that mankind can be reconciled with God—is how Lairesse involves the viewer as a participant in this encounter with Jesus.

Illuminated by the heavenly glow, Jesus is surrounded by a white cloth that reflects the light, creating a contrast with the dark background. Mary is revealing her child by unfolding this cloth. Lairesse thus presents Jesus as “the light of the world” (John 8:12). This became a familiar motif thanks to the print by Goltzius (see fig. 17) and a well-known engraving after Abraham Bloemaert.64 The motif was also attractive for the way that the cloth presages the shroud in which Jesus would be wrapped after his crucifixion. Another popular motif is the woman with the basket on her head: she is particularly recognizable from a print by Lucas Vorsterman after Rubens.65

As far as is known, this is the only time that Lairesse—in line with a long tradition—tackled a nighttime scene. The group of figures has been convincingly highlighted against the darkness in which a few half-illuminated secondary figures disappear. An ox and a donkey are traditionally present in this scene, symbolizing the groups for whom Christ’s message is intended: the Jews and the gentiles. In the seventeenth century, that association—which embroiders upon texts from the Old Testament—fell into disuse. Whereas Goltzius did depict the traditional ox and donkey, Lairesse only has a cow behind Joseph.66 The example of Goltzius is particularly important because of the Holy Family’s configuration, which Lairesse took over in a mirror image.67

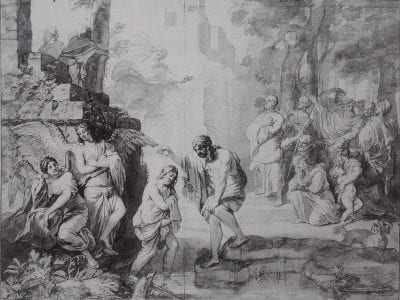

Circumcision

Mosaic Law stipulates that every Jewish boy should be circumcised eight days after birth (Luke 2:21). The theological meaning of this portrayal is twofold: the parents have accepted the Laws of Moses; and circumcision also makes clear that Jesus is a human being. The pain and the loss of blood are a foretoken of his Passion. Generally, as in Goltzius (see fig. 18), both Mary and Joseph are shown as pious onlookers. Lairesse diverged from this by having them respond differently to the circumcision (see fig. 12). Also in Rubens’s Circumcision Mary is looking away uncomfortably.68 Mary’s presence in the temple, although customary, is not correct in biblical terms. This is because the circumcision took place on the eighth day and, according to Jewish proscriptions, Mary would not yet have been welcome in the temple on that day.69 Rembrandt must have been aware of that when he set his etching of the Circumcision of 1654 in a stable (see fig. 27).70 The work by Lairesse has one striking parallel with Rembrandt’s Circumcision, painted for the stadtholder in 1646, which still located the scene in the temple: both have a kneeling child to the right of the main scene who is looking round at the viewer.71 Another figure in Lairesse’s painting looks outward: he has used the mother with a child on the left side to arouse empathy by involving viewers in experiencing relief once the circumcision is over.

The Jewish priest is carrying out the circumcision on an altar table (which evokes associations with the mass).72 Lairesse has portrayed the scribes as a disputatious group in the foreground to the right (whereas Goltzius still has them behind the main scene), thereby once again enhancing the viewer’s involvement. The chandelier above Jesus and the figure seen from behind with the large candle are also variants on the same motifs in the print by Goltzius. The isolated depictions of Mary and the man in the background in the center bowing his head—whom Lairesse transformed into Joseph—seem to be based (as mirror images) on a study of an engraving by Francesco Brizo after Ludovico Carracci (fig. 36).73 Lairesse placed the scene of the circumcision in an alcove inside the temple. His temple contains two pedestals above either side of the alcove, on which we can see the feet of statues. Although Lairesse must have known that the Mosaic Law forbids idolatrous graven images, the traditional representation, which rarely depicts a bare temple, seems to have been more important than decorum.

Adoration of the Kings

The extraordinary encounter between worldly powers and a family with a special child had already been depicted innumerable times, so there was no possibility of surprise.74 In the Adoration of the Shepherds, Lairesse added a certain degree of individuality in the playful yet elegant young shepherds and shepherdesses. He elaborated on this in the Adoration of the Kings (see fig. 13), with the engaging youngsters kneeling in the lower left corner, one of whom—along with the boy with the censer—is encouraging the viewer to become part of the spectacle. Lairesse will have seen something similar in the engraving by Lucas Vorsterman after Rubens’s Adoration in Mechelen, which also played a key role in working out the placement of the kings (fig. 37).75 The African king, in a somewhat isolated position in front of the evening sky, has been copied from Vorsterman’s print after another Adoration by Rubens, now in Lyon (fig. 38), that situates the scene inside a stable.76 Lairesse preferred an “antique” setting. Similarly to Goltzius’s print (see fig. 19), he chose to locate the event in the ruins of the palace of King David, referring to Jesus’ royal lineage. It is above all Goltzius’s comparable enclosure by the architecture that must have been going through Lairesse’s head when portraying the structures that surround the group, but he gives the figures more space and air, making his composition more balanced. His Mary, reminiscent of Van Dyck, and the red-cloaked king show his desire to depict a gracious ideal.77 This is how Lairesse responds to a number of prints in order to create an elegant and uplifting scene, appropriate for kings making the acquaintance of Jesus as God in human form.

The Adoration of the Kings is the only one of the series that was also issued as a print (fig. 39).78 Bringing the African king and the enclosing architecture further forward and cutting them off at the top gives the composition a relieflike quality with less depth. Lairesse also painted a second version in 1673 (fig. 40) that is almost square in shape and is structured more rigidly, parallel to the plane of the painting; the main figures have been given more space and the contact with the viewer has been broken.79 In this work Lairesse has adopted a more classicist approach. This has also taken him a step further away from Rubens. The cloaks, which were previously reminiscent of medieval princes, have acquired a Roman look; only the African king still reminds us of the Flemish master.80

Simeon’s Song of Praise

According to Luke, Jesus was presented to God forty days after his birth.81 To this end, the family went to the temple. The same visit also served for the ritual purification of Mary by sacrificing two doves. Lairesse depicted the events that preceded this presentation (see fig. 14). In the temple, Mary and Joseph first met Simeon and then the prophetess Anna. Both recognized Jesus as the promised redeemer, expressing their delight and praising God (Luke 2:30–32). Because the high priest is absent and because Simeon is not acting as a Jewish priest—as for example in a print by Paulus Pontius after Rubens (fig. 41) that will be discussed later—this scene does not depict the Presentation in the Temple but instead Simeon’s Song of Praise. Lairesse has thus shifted the scene from a Jewish ritual to the acknowledgment of the divinity of Jesus (Epiphany).82

The engraving by Pontius, based on the side panel of Rubens’s famous altar of the Deposition in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, was undoubtedly the source of inspiration for Mary’s pose, Simeon with Jesus, and the combination of Anna and Joseph, kneeling so that their heads are close together. Lairesse borrowed the figure of Simeon with his gaze raised heavenward but changed his liturgical clothing, perhaps for reasons of decorum. He turned Rubens’s prophetess Anna into a more idealized woman, and his Simeon also has a more youthful skin. Moreover, Lairesse’s composition exhibits a striking similarity in a number of ways to the engraving of the Presentation by Rémy Vuibert (1607–1652) from 1640 (fig. 42).83 The rounded shapes of the architecture in the background and the column with the curtains are similar, but he has also added the girl on the altar step and the standing figure next to her as figures that draw the attention to the main scene.

In contrast to Vuibert, Rubens, and a number of versions by Rembrandt, Lairesse chose to portray a temple without Jewish activities.84 Simeon is standing by a balustrade in front of an imposing piece of furniture. This must be a structure with the Ark of the Covenant, although it does not look much like it (see Lairesse’s representation of the Ark in his Heliodorus, fig. 43).85 The shape seems more to have been inspired by Jean Boulanger’s engraving after the altarpiece by Simon Vouet in the Minimes Convent in Paris (fig. 44).86 The heavily twisted “Solomon’s columns” do evoke direct associations with the temple of Solomon.87 The black area between those columns contains the tablets with the Laws of Moses and the (poorly legible) text of the Ten Commandments. The room is therefore recognizable as a Jewish temple. However, the lack of any reference to Jewish activity—plus the association with a Catholic altar—implies that Lairesse has in fact imbued an unspecified ambience of antiquity with “Christian” significance.

There is therefore a risk of anachronism, which Lairesse strongly disapproved of because of its violation of decorum, at least in his Groot Schilderboek.88 In his later Expulsion of Heliodorus (1674), he placed the Ark in the top left as a symbol of the temple of Solomon (see fig. 43).89 It radiates light, symbolizing the glory of God (shekhinah). A Jewish temple has unmistakably been depicted in this case and Lairesse has satisfied the requirement of decorum.

Around 1665, probably shortly before the series by Lairesse was produced, the Reformed artist Jan van Neck (ca. 1635–1714) was working on an altarpiece with the same subject for the Francophone Catholic church in Amsterdam. Originating from Liège, Lairesse would have been an ideal candidate for this commission, but perhaps he arrived in Amsterdam too late or was not interested. It is not known what became of the altarpiece itself; only Van Neck’s presentation drawing has been preserved (fig. 45).90 Van Neck stayed much closer to the example of Rubens in his altar design than Lairesse did. One striking iconographic difference is that a boy kneels with a large candle on the left of Van Neck’s drawing. He is dressed more as an altar boy than a temple servant and refers to Catholic worship and the procession of light, which is celebrated in honor of the purification of Mary as Candlemas. Although this boy also appears in the engraving after Rubens that both Van Neck and Lairesse studied closely, this motif referring to the liturgy is absent in the Lairesse work.91 He replaced him by the figures who draw the viewers’ attention, within and outside the picture, to the events taking place. Joseph and Mary are focusing exclusively on Simeon’s words, acknowledging their son as the promised redeemer. In Van Neck’s composition, Joseph hands over the offering. He is concerned about the obligations of Jewish law and therefore seems to be missing Simeon’s message.

Theological Meaning of the Infancy Cycle

Lairesse uses gestures and facial expressions in all the paintings. This is still somewhat understated in the Annunciation, but in the Adoration of the Shepherds a child and the woman with the basket on her head are looking at the viewer. In the Adoration of the Kings, a young page, the soldier on the left, and the African king are making contact with the viewer. Various figures act as intermediaries in Simeon’s Song of Praise. A young boy directs us to the main event where Joseph kneels and seems to have come from our world. Stairs also link our world with that of the painting, as in the Circumcision. The various ways that intermediary figures are used to create a relationship with the world outside the painting is typical of these works, scarcely playing any role elsewhere in his oeuvre. Lairesse uses this approach multiple times in a refined way in this series, seductively drawing the viewer in, with a smile. This lets him involve the viewer closely with the religious content of the paintings, encouraging meditation and contemplation. First of all, the viewer experiences joy at the birth of Jesus. This delight can also be seen in both the Jewish shepherding folk and the gentile kings. That joy is then tempered. In the Circumcision, a believer realizes that Jesus is suffering pain for the first time here and that it will culminate thirty-three years later in his ultimate suffering on the cross. And Simeon’s Song of Praise will make a biblically schooled viewer think not only of Simeon’s prophetic words but also his foretelling of Mary’s sorrows.

The theological meaning of the Infancy cycle is primarily the miracle of the incarnation of God (Annunciation, Visitation). Then there are witnesses of his birth as God in human form (the shepherds), and the Circumcision also confirms his human nature. The magi, who have been upgraded to kings, are honoring Jesus as the King of the Jews, and their gifts also symbolize both his divinity and his human nature. Simeon and Anna, finally, confirm that Jesus is the redeemer they have been promised. The believer experiences all these dogmas of faith through the eyes of those witnesses.

This religious and emotional identification links the series by Lairesse to the beliefs of the Counter-Reformation world. Unfortunately, we do not know for which ecclesiastical setting the series was produced, but one very likely candidate would be an ecclesiastical context such as that of Huy, where this series or a similar one must have hung on the wall to encourage both compassion and Catholic beliefs and values.

Conclusion

In the Infancy of Jesus, Lairesse produced an exceptional series of paintings for which there were few precedents. The series plays powerfully on the religious feelings of the viewer and is intended above all for Counter-Reformation reflection. Traditional iconography is essential for that end. As with Goltzius, Mary received all the attention because she is the mother of God incarnate; this would have been appropriate for a Counter-Reformation series for the Catholic south. Artistic considerations will also have encouraged Lairesse to make intensive use of the engravings by Goltzius. Lairesse attempted to improve on the example of Goltzius in his own unique way, doing the same things with compositions and motifs that he knew from Rubens and Rembrandt, which would seem to have stimulated his thinking on certain topics. He always added grace, idealization, and decorum to a setting and composition that he himself described as “genuinely Antique,” although he did not always adhere to it as strictly here as he did later. In his Infancy series, Lairesse seems to have looked at French or Italian graphic art only on rare occasions. One such exception is the print of the Annunciation by Villamena after Arconio, which Lairesse borrowed from fairly literally. This borrowing balances precariously on the verge of the “misuse” mentioned in the introduction, but he was otherwise very careful in inventing things for himself with his knowledge of many prints. He thus complied with what he would later describe in his Groot Schilderboek as “the proper, yes the necessary use” of prints: “The purpose that one has in inspecting and contemplating prints and drawings is twofold: first, to soothe and please our eyes; and second to enrich our thoughts.”92 This sequence of conventional religious subjects, in which Lairesse probably had to meet closely prescribed expectations, is an early high point in his religious oeuvre. Mislaid at some unknown moment, the series is now not only a reminder of the Catholic view of the world in the seventeenth century but also proof of the virtuosity with which the young Lairesse was once again able to bring well-known stories into the limelight.