This essay examines View of Ambon (ca. 1617), the earliest documented commissioned painting to adorn the Amsterdam headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The painting commemorates the VOC’s conquest of the South Pacific island of Ambon, showing the captured Portuguese fort at near center and, in the lower right, a medallion-like portrait of VOC officer Frederick de Houtman, who provided the map on which the painting was based. Investigating the combination of cartographic projection, perspectival recession, and portraiture in View of Ambon and related newsprints, this essay elucidates how the layering of seemingly objective pictorial modes constituted a visual rhetoric of reality and a sense of good order and governance overseas. Viewed in the VOC’s contentious sociopolitical landscape, however, View of Ambon ultimately illustrates how seemingly objective modes of picturing were inflected to express conflicting corporate and individual self-imaginings.

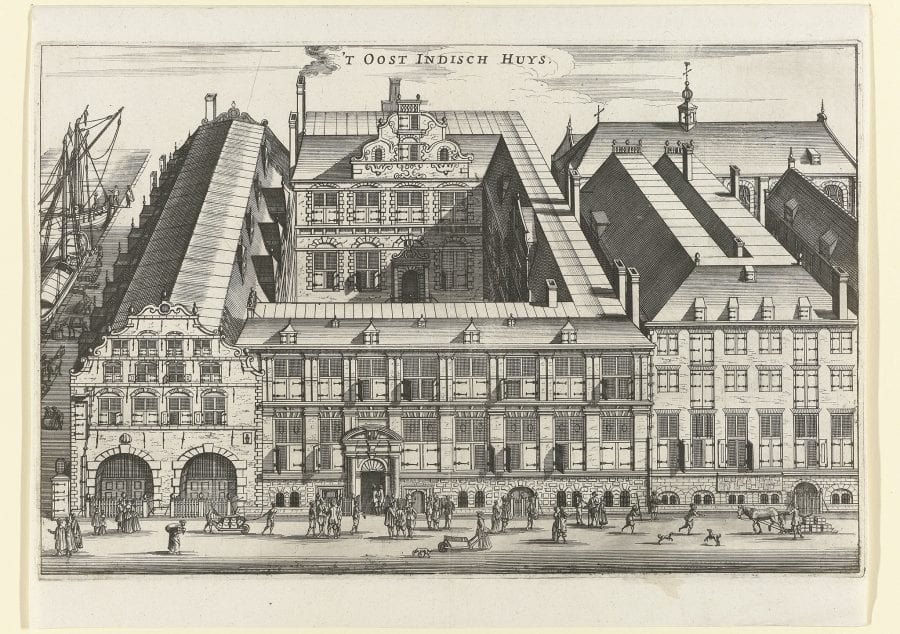

In 1617, the directors of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) commissioned a large-scale oil painting, presently known as View of Ambon (ca. 1617), for the Great Hall of their Amsterdam headquarters, the Dutch East India House (fig. 1). For nearly two centuries (1602–1800), the commercial, military, and diplomatic enterprises of the VOC, the world’s first joint-stock global trading company, would yield access to luxury Asian commodities in abundance. Dutch trade in such treasures as Chinese porcelain and silk, Japanese lacquerware, Indian pepper, and Ambonese cloves both fed and fueled European interests in all manner of exotica.

View of Ambon offered the VOC directors based in Amsterdam an all-encompassing, bird’s-eye view of newly conquered commercial territory. Ambon, one of hundreds of so-called Spice Islands in the South Pacific, is shown from above in the painting, blown up to monumental proportions and rendered with remarkable cartographic accuracy. For more than a century, this View of Ambon hung prominently beside the hearth in the Great Hall of Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House, commemorating the VOC’s 1605 victory over the Portuguese at Ambon and its first major overseas territorial acquisition.1

View of Ambon is the earliest recorded VOC-commissioned painting. Its production and early reception are remarkably and unusually well documented in the VOC archives in The Hague. The commission called on Frederick de Houtman (1571–1627), the former VOC governor of Ambon, to order “a skillful map” (eene bequame karte) “made of the island, the fortresses and the villages, with a perfect scale and compass orientation.” The work sheds crucial light on the VOC directors’ aesthetic prerogatives and the value ascribed to authentic, accurate, and “perfect” (perfecte) representations of the VOC’s overseas operations.2 Authorized and authenticated by de Houtman, an avid mapper of the southern hemisphere’s seas and stars and a faithful company servant, View of Ambon also testifies to the indispensable role that the VOC’s itinerant officers played in shaping a public image of the company’s overseas order and governance from an early date.

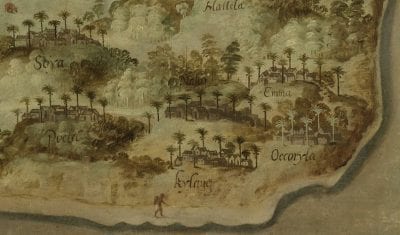

View of Ambon is painstakingly detailed, with a conspicuous air of pictorial objectivity. In the painting, the captured Portuguese trading post Fort Victoria resolutely occupies the near-center of the composition. Confidently rendered coastlines invite viewers to trace a slow, methodical course around Ambon’s lush clove-producing landscape. Details of Ambon’s flora, fauna, and fortifications are rendered in perspectival recession, giving order to the landscape and the pictorial space of representation. Noticeably absent are any sensationalizing details of Dutch conflict with Portuguese traders or indigenous inhabitants. Instead, minuscule calligraphic inscriptions, identifying local polities with which the VOC had or had not yet reached desired trading agreements, draw viewers close to the painting’s surface. Viewers are encouraged to dispassionately “read” the painting as they would an official VOC document (fig. 2).

While galleys and other vessels are depicted in Ambon’s politically troubled waters, a medallion-like cartouche frames an inset portrait of Governor de Houtman in the lower right corner, just to the right of a swordfish in profile (fig. 3). The portrait is evidently based on a three-quarter-length portrait that de Houtman himself likely commissioned upon his return from the East Indies (fig. 4).3 The painted portrait shows de Houtman wearing the gold chains awarded to him by the VOC, with a terrestrial globe at his elbow. It effectively conveys both de Houtman’s knowledge of the world and his commanding position in global commerce. The presence of the inset portrait in View of Ambon seems to credit de Houtman with both authorship of the map and administrative authority on the island.

Combining portraiture with cartographic and perspectival orientations and explanatory inscriptions, View of Ambon is a comprehensive, commanding, and decidedly corporate image of the VOC’s new territory. It is an image so multilayered that it evokes early modern Dutch cartographers’ processes of synthesizing numerous diverse source materials to produce a single, reliable, and “skillful map.”4 Not bound to any single, subjective point of view, View of Ambon may at first glance appear to provide an objective view of conditions on the ground on the island. However, by offering viewers a vantage point impossible to inhabit in the real world, View of Ambon departs from dispassionate documentary reportage and depicts the VOC’s operations from a considerable conceptual distance. Seen in historical perspective, what is most striking about View of Ambon is the extent to which its sober and seemingly objective visual rhetoric served both to signify stability abroad and to stabilize and support the rarified social and professional atmosphere that surrounded VOC directors and officers at home in the Dutch Republic.

This essay draws on scholarship by Kees Zandvliet, Elizabeth Sutton, Christi M. Klinkert, and others on the propagandistic potential of seventeenth-century Dutch cartographic prints and paintings.5 It explores what, in the context of VOC power and politics at the time, this grand hybrid composition concealed and revealed about the VOC territory of Ambon and its administration. Using View of Ambon as its starting point, the essay investigates the contentious sociopolitical landscape that led VOC directors to tighten their grip on the company’s public image around the time of the painting’s commission. It articulates how the VOC’s orderly and “matter-of-fact” modes of pictorial self-representation were, in fact, “made-to-order.”

View of Ambon abided by the a priori pictorial conventions of cartography, perspective, and portraiture, all of which were long esteemed for providing true and trustworthy likenesses of their subjects. In doing so, View of Ambon promised an authoritative view of the VOC’s administrative order overseas. This was a view that would order and shape viewers’ perceptions of the VOC’s enterprises. Hung beside the hearth of the Great Hall in Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House until the late eighteenth century, View of Ambon was, however, subject to the pressures of the sociopolitical landscape that it inhabited. Archival sources reveal that the made-to-order painting elicited debate—even disorder—within the walls of the VOC’s Amsterdam headquarters.6 VOC Admiral Steven van der Haghen (1563–1621), whose fleet conquered Ambon in 1605, was incensed by the inclusion of de Houtman’s portrait in the painting and, in 1620, demanded comparable representation in a company painting—and in company history.7 Amply documented debates about the painting’s skewed portrayal of historical facts reveal keen awareness of the indispensable role of art in both company and individual self-image formation and illuminate the extent to which this “skillful map” was “made-to-order” public opinion.

Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House

By the time of the installation of View of Ambon (ca. 1617), Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House was the well-established administrative headquarters of the Amsterdam Chamber of the VOC. Beginning in April 1603, the Amsterdam Chamber rented the imposing Arsenal on the Kloveniersburgwal from the city of Amsterdam as its base of operations, auction site, and meeting place for discussions about trade policy in the East Indies.8 Built in the mid-sixteenth century and formerly occupied by one of the city’s civic guard companies, the Kloveniersdoelen, the Arsenal underwent a series of extensive additions and renovations to suit its new identity and functions as the Dutch East India House. In particular, the 1606 addition of a new wing, probably designed by esteemed city architect Hendrick de Keyser, afforded ample office and meeting space for the chamber’s board of directors (Bewindhebbers).9

The board of directors, an elite group of top VOC shareholders, met two or three times each week in the building’s Great Hall, where View of Ambon was displayed.10 Dutch designer and printmaker Simon Fokke’s 1768 etching of the Great Hall, the only known print to show the hall’s early modern interior decoration, provides a sense of its extravagant furnishings and of the privileged social and professional milieu of the VOC directors (fig. 5). The esteemed directors not only decided vital commercial, military, and diplomatic matters but also deliberated on aesthetic aspects that shaped the VOC’s public image, to which the 1617 record of the commission of View of Ambon attests.

Although the Amsterdam Chamber’s business was largely conducted by an exclusive group of directors behind closed doors, the Dutch East India House was a highly visible civic landmark and tourist attraction from the early seventeenth century on. In the same year that the Amsterdam Chamber first rented the building (1603), the old city walls beside it were demolished, leaving ample canal access for small vessels and for the loading and unloading of global commodities to proceed in public view.11 A mid-seventeenth-century print portraying the Dutch East India House’s exterior gives a sense of the monumental scale of both the building and the company’s commercial operations, showing several ships moored at the building’s side (fig. 6). Horse- and hand-drawn carts, shuttling heavy bundles, are dwarfed by the building’s formidable and stately facade.

With newly constructed spacious basements and attics, the Dutch East India House was the primary storage site for the VOC’s most precious commodities. It burst with expensive textiles and fragrant spices, until larger warehouses were constructed elsewhere in city.12 Interestingly, the frequently cited 1701 description of Amsterdam as “the warehouse of the world, the seat of opulence, [and] the rendezvous of riches” resonates with much earlier published accounts of the sights and smells in and around the city’s Dutch East India House.13After visiting all the “marvels” of Amsterdam in 1617, the year of the commission of View of Ambon, French writer and traveler Pierre Bergeron recorded that it was to the Dutch East India House, with its long halls “full of spices, pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, mace, cinnamon and others,” that the city owed all of its “grandeur, riches, & magnificence.”14

The stately decoration of the Dutch East India House’s interior caught the eyes and moved the pens of early seventeenth-century visitors as well. Paintings depicting “new” Asian lands and places of interest (“nieuwe ghestaltenissen en overzeesche ghestichten”), including the imperial court of China (“het hof des Conincx van China”), adorned the walls of its Great Hall as early as 1611. This we know from seventeenth-century Dutch historian Johannes Isacius Pontanus’s multivolume history of Amsterdam, Rerum et Urbis Amstelodamensium Historia (Latin edition 1611; Dutch translation 1614).15 Pontanus’s history of Amsterdam is remarkable for its inclusion of a chapter devoted solely to the Dutch East India House and its activities. The chapter is situated within the section devoted to the city’s other monuments of civic pride and, particularly, to the city’s loci of social and economic welfare, including its orphanage, Rasphuys and Spinhuys (correctional institutions for men and women, respectively), and Waegh (Weigh House). The presence of the Dutch East India House in this section reveals not only how civic and company pride were deeply entangled at the time but also how the company and its commerce were esteemed for contributing to Amsterdam’s general well-being.

The frontispiece to Rerum et Urbis Amstelodamensium Historia echoes these themes, depicting the entrance of the so-called Indies onto Amsterdam’s civic stage (fig. 7). In the frontispiece image, barrels and bundles of trade goods lie at the foot of a pedestal in the image’s upper register that supports traditional heraldic emblems of Amsterdam: a cog ship, three Saint Andrew’s crosses, and the imperial crown of Maximilian I. Traditional emblems are prominently accompanied by a cross-staff and quadrant—essential instruments of early modern Dutch overseas navigation. Emerging from darkness, at the far left and right sides of the composition, generalized “Indian” and “Eskimo” figures personifying the realms to the far north and east that Dutch fleets had only just recently endeavored to reach sneak a peek at Amsterdam’s purported greatness. The frontispiece testifies to the reknown of Amsterdam’s global trading enterprises, which at the time were centered nowhere more conspicuously than at Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House.

The VOC’s Administration of Representation

Paintings installed in the Great Hall surely impressed visitors to Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House from an early date. Interestingly, however, Prince Johan Ernst of Saxony, who visited the Great Hall in 1614, was reportedly not impressed by many of the paintings that he saw. More to his taste was the hall’s large sea chart, in which “the Asian navigation with all winds and harbors was depicted, beautifully drawn on parchment with pen and partly painted.”16 Sea charts and other cartographic artifacts occupied considerable wall space in the Great Hall and figured as prominently as the paintings of Asian landscapes in the VOC’s self-promotional visual rhetoric. As historian Kees Zandvliet explains in his seminal study of early modern Dutch cartography and Dutch global trading companies, the painted and printed maps adorning the “geopolitical theaters” of VOC boardrooms blurred the boundary between cartography and art. They not only facilitated the decision making of the VOC directors but also aestheticized and celebrated the company’s overseas operations, commemorated events, and impressed distinguished visitors.17

Given the popularity of the Dutch East India House among foreign dignitaries, it is worth considering how the maps and charts of Asian trading centers on display figured as extensions or projections of a sense of European ownership of the East Indies. The multilayered perspectives offered by cartographic works, including View of Ambon, could position European viewers in the exotic space of the East Indies while simultaneously holding that space at a distance, as an object of viewers’ rational consideration and “cognitive possession.”18View of Ambon was surely intended to fit an already established decorative scheme that privileged cartographic descriptions as the means of both representing and rationalizing the VOC’s operations.

The VOC directors’ administrative decisions, in and around 1617, concerning the production of maps and sea charts bear directly on the commission and the cartographic depiction of View of Ambon in the same year. At the time, the directors at Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House oversaw not only the VOC’s essential commercial and financial operations but also set the rules regulating the recording and reporting of geographical information by the VOC’s overseas officers. The VOC had naturally been concerned from the start with collecting and compiling geographical information for navigational, practical, and tactical purposes, employing numerous cartographers and surveyors at home and abroad. As early as 1604–5, the company equipped ships’ pilots with sheets of paper bearing predrawn compass lines, facilitating the production of collatable cartographic knowledge of southern seas and coastlines. In fact, little-known shores were sketched on the VOC’s prelined paper during the voyage of the VOC fleet led by de Houtman’s eventual adversary, Steven van der Haghen, in 1604–5.19

The 1610s witnessed increased concern about the VOC’s modes of cartographic representation and their regulation. In January 1614, VOC Accountant-General of the East Indies and later infamous Governor-General Jan Pietersz Coen wrote a plea to VOC directors for the production and verification of a “padrón real”: a large-scale map of the full extent of the VOC’s chartered trade zone (octrooigebied). Evidently Coen envied and sought to emulate the regulated cartographic productions of Portugal’s state-sponsored overseas trading enterprises, already well underway in the early sixteenth century.20 Such a document would aid in organizing and implementing Coen’s plans to secure and safeguard a clove monopoly in the Moluccan Islands and a nutmeg monopoly in the Banda Islands via diplomacy or, in some cases, unbridled force.21

Zandvliet identifies the years from 1614 through 1619 as most crucial in the development of the VOC’s mapmaking agency in Amsterdam. In these years, the company issued several ordinances concerning the collection and dissemination of geographic information. Overseas pilots were instructed to make “perfect observations” and collect geographical knowledge on a daily basis, in order to further the company’s goals of military and commercial control in Asia. A newly drafted labor contract in August 1616 reflected the directors’ proprietary attitude toward the textual, pictorial, and cartographic representations of geographic information. Articles 121 and 122 demanded that all overseas officers’ documents be handed over to the directors in the Dutch Republic. In a revised December 1616 labor contract, Article 39 instructed company officials to keep logbooks of their voyages, to leave copies of their observations in Bantam on Java (a rendezvous point for the VOC), and to hand in their original logbooks upon returning to the Dutch Republic, without exception.22

In addition to commissioning View of Ambon in 1617, the VOC directors appointed Hessel Gerritsz, a mapmaker and modest investor (600 guilders) in the Amsterdam Chamber, as the first official cartographer of the VOC in that year.23 It was to Gerritsz that all overseas officers’ journals, maps, and drawings would be sent, so that Gerritsz could collate and correct navigational and administrative maps and charts of the VOC’s area of operations. In 1619, the VOC gained further control over the representation of geographic information when it received an exclusive privilege from the States-General for the production and reproduction of maps and descriptions of its area of operations. No such map or description was permitted to be published or copied without the express permission of the VOC directors. Anyone who flouted this rule stood to incur an impoverishing fine of 6,000 guilders.24 Clearly, the VOC’s endeavors to control and keep secret the collected information echoed the policies of Portuguese traders, whose initial commercial successes depended on secrecy and “the monopolization of logistical and navigational information” relating to southern maritime trade routes.25

View of Ambon’s “Face Value”

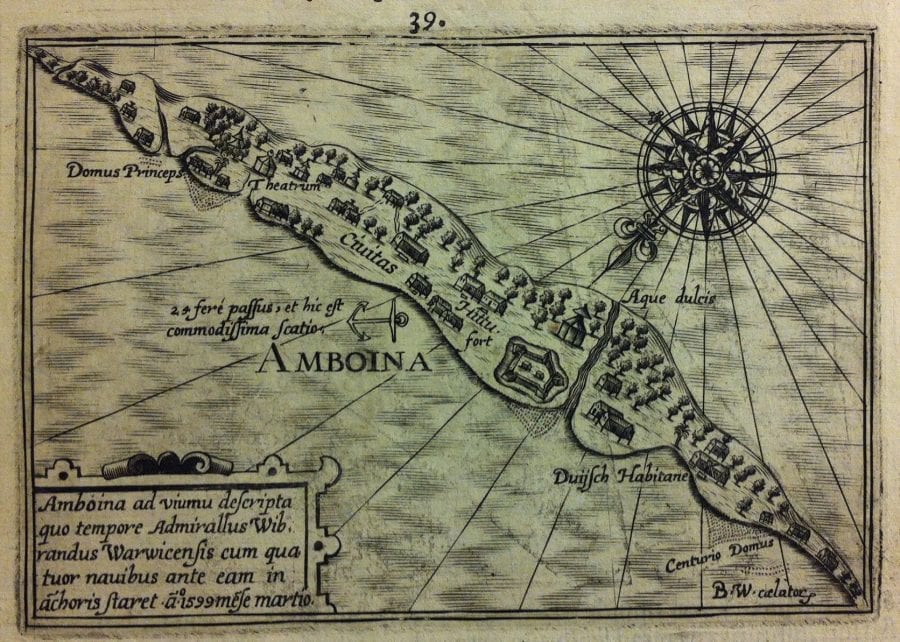

The VOC’s 1605 conquest of Ambon was hardly kept secret from the Dutch public, however. As the VOC’s first major overseas territorial acquisition, news of Ambon spread quickly. Pontanus’s above-discussed history of Amsterdam (1611, 1614) includes a brief account of the conquest made by VOC Admiral Steven van der Haghen, as well as a quasicartographic image of Ambon (fig. 8). The image is best characterized as a highly schematic imagining of the island rather than an accurate or objective representation. It shows only the island’s lower peninsula, foregoing cartographic accuracy in favor of aesthetically pleasing symmetry.

A newsprint issued almost immediately after the conquest similarly combines a fantastical rendering of Ambon with a brief textual account. Captioned “a true and memorable depiction of the conquest of the island and castle of Amboina” (1606), the multisheet print was issued by VOC bookkeepers in Amsterdam, Barend Lampe and G. Kick.26 The print’s profile View of Ambon’s mountainous coastline is crowned by a calligraphic inscription and celebrates the VOC’s suppression of the Portuguese fleet and the capture of Ambon’s Nostra Senhora de Annunciada, the Portuguese base of operations that the Dutch promptly renamed Fort Victoria. Lampe and Kick, who issued the print on their own private initiative, dedicated the print to Amsterdam’s VOC directors as well as to van der Haghen, the admiral who not only led the victorious fleet at Ambon in February 1605 but also captured the Portuguese fort on nearby Tidore in May 1605. The print and, perhaps, the high honor accorded van der Haghen in the print’s inscription evidently displeased the VOC directors. Although the Amsterdam directors paid Lampe and Kick 50 Flemish pounds (300 guilders) for their initiative, they halted production of the print and instructed the bookkeepers not to take the company’s image making into their own hands again.27 Van der Haghen’s conquest, however, was a historical fact that the directors would have to contend with later, when in 1620 van der Haghen raised a protest against View of Ambon.

Ambon is an island in the Moluccan archipelago located to the east of the islands of Sumatra and Java in the South Pacific. Named Amboina by the Portuguese, who arrived in the second decade of the sixteenth century and claimed it as territory in 1527, Ambon was a primary source for cloves and a nodal point on Eurasian trade routes. Dutch seafarers first conducted trade there in 1599, when four Dutch ships commanded by Wybrand van Warwijck and Jacob van Heemskerk safely reached the island’s shores.28 Shortly thereafter, in 1601, the published travel journal of officer and explorer Jacob van Neck, who traveled with that fleet, presented Dutch readers with schematic images of Ambon’s topography and inhabitants.29 The bird’s-eye View of Ambon from van Neck’s journal offers a simplified depiction of the island, with its diverse residents pictured and labeled in the foreground (fig. 9).30 In the text of his journal, van Neck amply describes the many “things there to be had marvelously cheape,” writing that on the island “a man may have 80 oranges for a button.” Evidently astonished by the gracious hospitality of Ambon’s inhabitants, van Neck lauds Ambon and the East Indies generally as a place of paradisiacal abundance—a place where “so great store of all sorts of fruites” could be obtained for the meager price of “one Tinne Spoone.”31

VOC Admiral Steven van der Haghen was similarly received by the Ambonese population on two occasions. In 1600 and 1605, local rulers gave van der Haghen a warm and generous welcome and promised to grant monopoly contracts on cloves to Dutch merchants.32 Portuguese traders’ attempts to force the island’s clove trade into their hands had weakened their relations with the island’s population, who by this time viewed Portuguese missionaries’ efforts at Catholic conversion with contempt. Van der Haghen’s method of operations struck a positive note with Ambon’s inhabitants. He operated by negotiation and contract, rather than by force, whenever possible. When van der Haghen’s fleet arrived in 1605, local rulers recognized the Dutch sailors and soldiers as fellow enemies of Portugal and offered support for a Dutch assault on the Portuguese fortress on the island.33 The time proved ripe for the VOC’s establishment of a permanent base of Dutch operations on Ambon, and van der Haghen’s fleet successfully drove the Portuguese from their territory in the same year. VOC directors then appointed Frederick de Houtman, not van der Haghen, as the company’s first governor of Ambon (1605–11).

Because the VOC’s cartographic archive was well guarded, it was not until the creation of View of Ambon that a large-scale, semipublic image accurately depicted the island’s coastal contours. View of Ambon’s cartographic and conceptual contours reflect the observations, calculations, and craftsmanship of two VOC affiliates. The first was de Houtman, retired governor of Ambon and a leading figure in the charting of seas and stars of the southern hemisphere for the so-called voorcompagnieën (precompanies) and the VOC alike. The second, David de Meyne (1569–before 1620), was the engraver and mapmaker to whom the painting is attributed.34 Following de Houtman’s return to Holland, Amsterdam’s VOC directors in 1617 commissioned him with the task of providing “a skillful map” (eene bequame karte) of Ambon, “with a perfect scale and compass orientation.”35 As the earliest recorded commission for the decoration of the Great Hall of Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House, View of Ambon testifies to the ways in which cartographic accuracy and seeming objectivity served not only the VOC’s practical and tactical purposes but also its self-promotional visual rhetoric.

View of Ambon shows the island as though viewed from above. The viewer’s eye passes easily over what was, in reality, quite mountainous terrain.36 Close inspection reveals that the island’s villages are neatly labeled for identification, so that the island’s local rulers and power centers are, in a manner, represented on the map. The village of Hyto (also Hitoe, Hietto, or Hiettoelamma) in the upper left possesses a number of large buildings that signal its significance in the local political landscape. Thirty other Ambonese villages acknowledged Hyto’s authority around the time of the painting’s creation.37 Larger-than-life and at near-center in the composition stands Fort Victoria, surrounded by neatly laid streets, buildings, and groves at the end of a long perspectival axis. Layered cartographic and perspectival pictorial modes abide no single, subjective viewpoint and thus present a seemingly objective view of the island. Textual inscriptions and overlapping orientations work against viewers’ perceptions of spatial recession, enhancing the painting’s two-dimensional and documentary character. The painting elicits an impression of information dispassionately collected, collated, and laid out on a surface. The well-ordered assemblage of cartographic and commercial information ultimately reflects and represents the all-encompassing vantage point of the VOC’s formidable corporate body of authority.

The pictorial order and seeming objectivity of View of Ambon certainly assured seventeenth-century viewers that the island was held in good administrative order by the VOC and, particularly, by the island’s first Dutch governor, de Houtman. Conspicuous in the painting is the space devoted to de Houtman’s portrait, framed by an elaborate cartouche that claims more pictorial space than the depiction of Fort Victoria. Flanked by dolphins and trumpeters and surmounted by the figure of the sea god Neptune, de Houtman gestures with his cane to Ambon’s fort complex. His cane aligns with the complex’s perspectival axis and thus aligns the painting’s pictorial order with a sense of de Houtman’s capacities for administrative order.

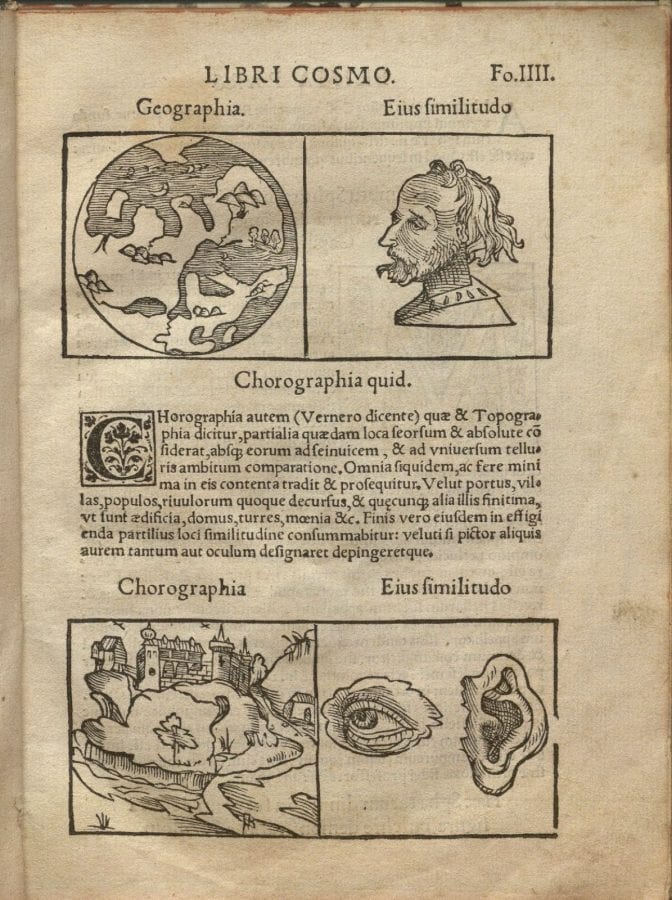

With its inclusion of de Houtman, View of Ambon not only combines cartographic and perspectival orientations but also merges two pictorial modes that were long esteemed for providing true and faithful likenesses of their subjects: mapmaking and portraiture. Indeed, the painting’s given Dutch title, Gezicht op Ambon, echoes this merger of modes, as the Dutch term gezicht can signify a “view” or a “sight” as well as a “face” or “countenance.” The link between mapmaking and picture making dates to antiquity—to at least as early as Ptolemy’s Geography (ca. 150 CE). Importantly, it is treated not only in scholarship on the history of cartography but also in scholarship on early modern Dutch visual culture and, particularly, in Svetlana Alpers’s study of Dutch art, The Art of Describing (1983).38

As Alpers writes, in his Geography Ptolemy aimed to articulate and “distinguish between the measuring or mathematical concerns of geography (concerned with [representing] the entire world) and the descriptive ones of chorography (concerned with [representing] particular places)” via an analogy with picture making. Ptolemy’s analogy, that “geography is concerned with the description of the entire head, chorography with individual features such as an eye or an ear,” evokes portraiture, and the training and skills of practitioners of geography and chorography correspond to those of the mathematician and the artist respectively.39 Renaissance humanist and mathematician Petrus Apianus gave pictorial expression to this analogous relationship in his Cosmographia (first edition 1524), in which the illustration of geography is achieved by pairing images of a world map and a head in profile, and the illustration of chorography juxtaposes a city view, an ear, and an eye (fig. 10).

For Alpers, Ptolemy’s analogy offers an antique pedigree for her ambitious argument concerning the overall descriptive nature of seventeenth-century Dutch art. She maintains that Dutch pictures and modes of picture making blur the distinctions between measuring, recording, writing, and picturing in a manner that is resonant with early modern understandings of the relationship between seeing and knowing.40 Klinkert, a scholar of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed Dutch news-maps that frequently combine cartography and portraiture, addresses the antique tradition of chorography as well, noting that Ptolemaic “chorography implies objectivity and precision.”41 Worthy of emphasis here is the fact that Ptolemy’s geography and chorography are not offered as analogous to picture making generally but rather to the specific artistic genre of portraiture, a genre esteemed for its capacity to preserve true and factual likenesses of its subjects at least since Pliny’s Natural History (ca. 79 CE). This detail goes unmentioned in the scholarship of Alpers and Klinkert. For this essay, the connection underlines the notion and perhaps the early modern viewer’s understanding of View of Ambon as a gezicht (view, face): a true and accurate likeness intended to be taken at face value.

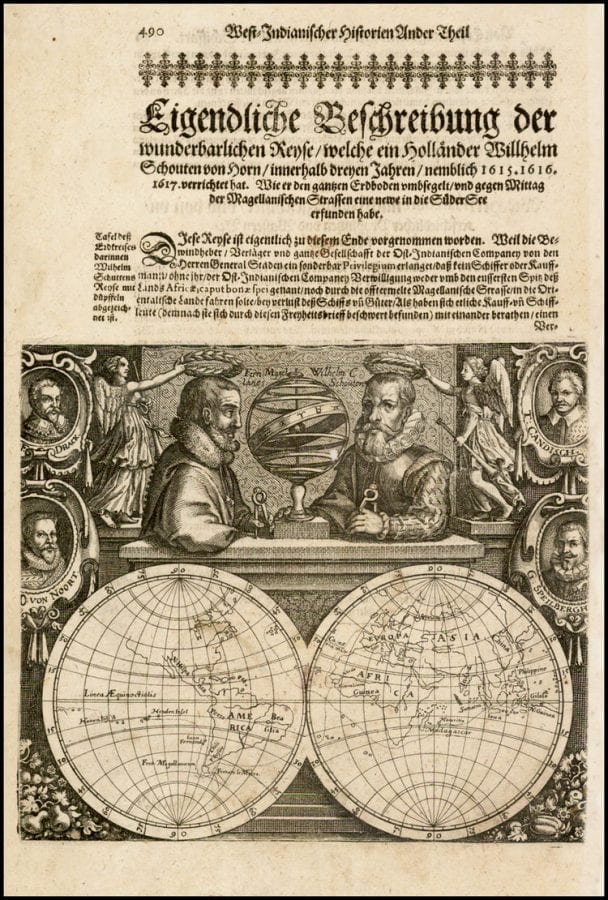

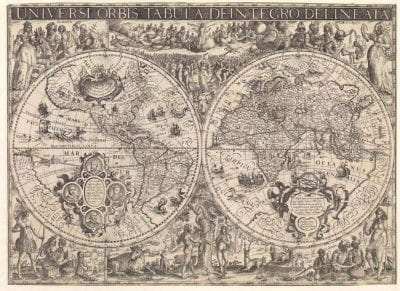

In Dutch prints predating View of Ambon, the merger of cartography and portraiture did often promote a reliable likeness of a group or corporate identity. Such prints could also serve to commemorate singular individuals’ contributions to specific corporate objectives. Engraver and mapmaker David de Meyne, credited with co-authorship of View of Ambon, surely understood the potency of this hybrid pictorial form, as his earlier printed works combine maps, views, and portraits. In 1610, for example, de Meyne issued Universi Orbis Tabula De-Integro Delineata, a large world map embellished with inset portraits of the world’s circumnavigators (fig. 11). In de Meyne’s composition, the first Dutch circumnavigator Olivier van Noort (circumnavigation of 1598–1601) joins the good company of his predecessors Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake, and Thomas Cavendish. The mens’ four faces, framed and united by an elaborate cartouche and laudatory inscription, largely fill the space of the wide Pacific Ocean that they famously traversed. Van Noort, Magellan, Drake, and Cavendish are thereby inscribed into the new, more accurate, and more comprehensive worldview that their commercial and exploratory voyages helped to create.

De Meyne’s format echoes that of the perhaps better known world map on Mercator’s projection that was issued by Jodocus Hondius the Elder (1563–1612), Nova et exacta totius orbis terrarum descriptio geographica et hydrographica (1608) (fig. 12). Here, the portraits of the four circumnavigators are joined by Ptolemy and are arranged chronologically in linked cartouches, with inscriptions of the dates of their voyages. Miniature inset maps show their routes and the changes made to the “world picture” as a result. Inhabiting the space of the map given over to the largely unknown and unmapped Antarctic, the portraits arguably serve to fill an information gap and aesthetically balance Hondius’s composition.42 Such portraits, however, provided much more than mere filler or decoration. The consistent addition of portraits to Dutch printed maps in the seventeenth century would elevate Holland’s illustrious seafarers to heroic and legendary status in the emerging nation’s history.43

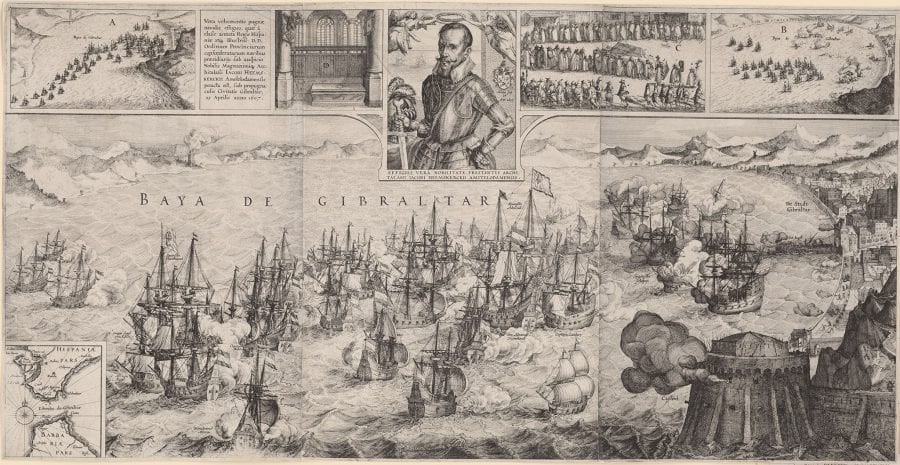

Roughly coeval with the world maps by de Meyne and Hondius, Claes Jansz Visscher’s large newsprint, The Battle of Gibraltar (1607), similarly combines a portrait, a map, and multiple bird’s-eye views to commemorate maritime heroism (fig. 13). In this case, the figure honored is Admiral Jacob van Heemskerk. Van Heemskerk was employed in 1599 by Dutch merchants and was among the first Dutch seafarers to set foot on Ambon’s shores. In 1607, he commanded the Dutch fleet that took Spanish ships by surprise at the Bay of Gibraltar and ultimately decimated the Spanish fleet. Visscher’s newsprint presents a profusion of visual information ordered and organized by a framing apparatus, uniting diverse parts of the battle narrative into a cohesive whole. The exacting pictorial logic of each of the newsprint’s component parts appears to echo and uphold the decisiveness of the Dutch military victory.

Paying tribute to van Heemskerk, whose victory in the Battle of Gibraltar cost him his life, Visscher’s 1607 print includes a centrally placed portrait of the admiral. It honors van Heemskerk’s singular and unique contribution to a corporate objective and thus resonates with the composition of View of Ambon, installed in the Dutch East India House only ten years later. View of Ambon, combining cartographic and perspectival views of a contested site with the portrait of a figure of seemingly singular importance in the territory’s administration, warrants consideration alongside these printed precursors. Its composite character conveys the geographic reach of a corporate entity, while also distilling the deeds of many into a single body. In the case of View of Ambon, a corporate view is advanced via the inclusion of a single face—that of Ambon’s first Dutch governor, de Houtman.

A View “Made-to-Order”

View of Ambon was purpose-built for its original location in Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House, and its aim was to convey a wealth of cartographic and chorographic visual information in an accurate, orderly manner, which could favorably shape and orient viewers’ perceptions of the VOC’s good order and governance overseas. Not everyone, however, took the painting at face value, and it became the subject of heated controversy among company officers in 1620. How could the calculated contours of “a skillful map” convey anything other than dispassionate and factual geographical information? Could the painting’s faithful portrait of Governor de Houtman conceal historical facts pertaining to Ambon’s conquest?

When the VOC directors commissioned View of Ambon, they demanded from de Houtman “a skillful map” with “a perfect scale and compass orientation.”44 Reading between the lines of the text of the painting’s commission, and in light of scholarship on de Houtman, we might posit that, for de Houtman, the words “skillful map” connoted not only faithful replication of geographical reality but also the suave sheathing of historical fact in a veneer of self-glorifying visual rhetoric. De Houtman was not only a faithful company servant but also a skillful self-promoter. The above-discussed three-quarter-length portrait of de Houtman, posed with gold chains and a globe, attests to this. In the map of Ambon that he co-produced, we must note that the directors’ demand for “a perfect scale” goes unheeded. The island’s fortifications, groves, and commercial traffic are increased to monumental proportions in View of Ambon. De Houtman’s portrait occupies the corner that might otherwise display the map’s scale in duytsche mylen (Dutch miles). No portrait is mentioned in the text of the commission, and it is entirely possible that de Houtman himself insisted on its inclusion, as a measure of his self-perceived magnitude in the VOC’s sociopolitical landscape.

Intriguingly, close inspection of View of Ambon reveals that the contents of two cartouches, below and beside the portrait of de Houtman, are overpainted. Did they bear inscriptions lauding de Houtman’s service and his representative status in Ambon, in the VOC, and in the painting? Their conspicuous erasure suggests that, in spite of the pictorial order of View of Ambon, conceptual closure in the painting is not achieved. Zandvliet and others maintain that inscriptions in the cartouches were obliterated in response to a two-year-long protest, launched in 1620, by Admiral Steven van der Haghen, the conqueror of Ambon.45 He confronted the VOC directors, presumably in the Great Hall, in an effort to inscribe himself into View of Ambon and into VOC history, in de Houtman’s place. Archival records of van der Haghen’s protest reveal that the made-to-order visual information contained in View of Ambon could be erased, overwritten, or made subject to omissions according to the desires of its patrons, creators, and, importantly, its viewers. Like the geographical domain that it represented, the representational surface of View of Ambon was itself a site of contestation.

Shortly after returning from a VOC mission in 1619, van der Haghen likely saw View of Ambon in the Great Hall of Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House and grew justifiably alarmed. Van der Haghen had played a more critical role in the conquest of Ambon and in the establishment of Dutch trade on the island than did his fellow VOC serviceman de Houtman. Slighted by the absence of his own presence in View of Ambon and evidently concerned with “losing face,” van der Haghen protested the inclusion and prominence of de Houtman’s portrait in the painting. A crucial source for van der Haghen’s protest is the journal of VOC lawyer Arnoldus Buchelius (1565–1641) who, in the early 1620s, commented on van der Haghen’s opposition to the skewed historical facts portrayed in View of Ambon.46 Buchelius’s journal entries point out the directors’ failure to produce a true and factual likeness of Ambon while documenting company officers’ keen awareness of art’s indispensable role in shaping both corporate and individual self-imaging. Moreover, they reveal the extent to which the VOC’s made-to-order pictorial rhetoric could be made to express discrepant corporate and individual self-imaginings.

In service to the VOC from 1619 to 1621, the scholar and lawyer Buchelius had a privileged, insider’s view of VOC operations, both the reality and as represented in the painting. We know from his personal journal that, by the summer of 1620, Buchelius had visited the Great Hall to admire View of Ambon with its “true-to-life” portrait of Frederick de Houtman.47 Evidently inspired by the painstakingly precise renderings of Ambon’s flora, fauna, and fortifications, Buchelius kept sketches of the painting in his journal. On numerous dates over the course of roughly one year, he penned paeans to Steven van der Haghen, Ambon’s indisputable conqueror. In the summer of 1620, for example, Buchelius wrote that van der Haghen was “the first conqueror of Ambon and several of the Moluccan islands in the name of our United Netherlands . . . in his voyages he performed exemplary service.” “With wonderful good fortune and God’s grace,” Buchelius wrote, “he [van der Haghen] conquered King Philip the II’s mighty and magnificent fort of Amboina, restored expelled Ambonese citizens, and brought the whole island of Ambon and its neighbors in the archipelago under Dutch rule.”48 A 1621 journal entry laments that van der Haghen’s conquest was “the fruit and profit of another.” “For all of his service he [van der Haghen] has not received recompense while the Company has regaled and celebrated de Houtman as the protector” of Ambon.49 The magnitude of this oversight is expressed in a 1621 journal entry in which Buchelius remarks that de Houtman himself acknowledged it. “Even de Houtman,” Buchelius wrote, “admits that van der Haghen was the conqueror.”50

Precisely why van der Haghen was not represented in View of Ambon is still a mystery. Zandvliet and others have posited several likely reasons. First, the VOC’s directors were surely upset by the fact that, in 1605, van der Haghen conquered Ambon in the name of the States-General, rather than in the name of the VOC. Whether this was an innocent misstep or purposeful slight on van der Haghen’s part is unknown. In Zandvliet’s view, this explains why the Amsterdam directors forbade the issuance of the above-mentioned 1606 newsprint, commissioned by VOC bookkeepers Lampe and Kick, which honored van der Haghen’s role in the conquest and establishment of Dutch trade on Ambon.51

The Amsterdam directors may have withheld honors due to van der Haghen for another reason: van der Haghen’s affiliation with opponents of the VOC’s military enterprises. At the time of the painting’s commission, van der Haghen was suspected of opposing the unrelentingly militant policies of the then-reigning VOC governor-general of the East Indies, Jan Pietersz Coen.52 In the 1610s, Coen’s insistence that the VOC establish monopolies on spices by force undermined the pacifist stance of Coen’s superior, VOC governor-general and doctor of law Laurens Reael, whom van der Haghen supported. Both Reael and van der Haghen left the East Indies in 1619. Coen took the city of Jakarta by force in May of that year and decimated the indigenous population of the Banda Islands shortly thereafter.53 Van der Haghen’s approach to trade with indigenous populations, as mentioned above, was entirely different, relying on negotiation, contracts, and diplomacy whenever possible.

Finally, van der Haghen was perhaps denied representation in View of Ambon—and in VOC history—as a result of his suspected “papist sympathies.”54 Mere suspicion of this offense could have ruffled Amsterdam’s staunchly Calvinist VOC directors. Some or all of the above-discussed factors may account for the absence of van der Haghen’s visage in View of Ambon—and in any other known painting, for that matter. His likeness is, in fact, known only from a mid-seventeenth-century print, in which he bears a striking and suspicious resemblance to a confirmed papist and protagonist in the expansion of Portuguese global commerce, King John III of Portugal (r. 1521–57) (figs. 14 and 15).

Although van der Haghen was the indisputable conqueror of Ambon, de Houtman was an indispensable administrator, and the many ways in which de Houtman was worthy of recognition must also be noted. As early as the 1590s, de Houtman and his brother Cornelis undertook risky missions to acquire cartographic and navigational knowledge of the southern seas. Their undertakings were funded by ambitious Dutch merchants prior to the founding of the VOC. In 1592, the brothers returned to the Dutch Republic from a particularly productive commercial and cartographic espionage mission in Lisbon.55

For de Houtman’s overseas enterprises before his period of VOC service, Pontanus’s history of Amsterdam proves again to be a crucial source. Pontanus’s chapters are sparsely illustrated until the reader reaches the section concerning Dutch navigation and the early Dutch voyages to Asia. Chapter 24, in particular, is richly illustrated with maps and images of Asian flora and fauna that add luster to the account of the first-ever Dutch fleet to reach the East Indies in 1595—an account compiled largely from the letters of the fleet’s admiral, Cornelis de Houtman, Frederick’s brother.

Both de Houtman brothers participated in the famous first fleet. The roundtrip voyage proved that Dutch overseas navigation and trade were possible and provided the impetus for subsequent exploratory and commercial ventures. The brothers’ second voyage together departed in March 1598. On this voyage, Frederick de Houtman fell captive to the sultan of Aceh in northern Sumatra and was held prisoner for nearly two years. Nevertheless, he managed to undertake scholarly and scientific investigations during his captivity on Sumatra, contributing significantly to the advancement of Dutch technologies of commerce, communication, and navigation.

Upon his release and return to the Dutch Republic, de Houtman took it upon himself to make his findings public. In 1603, he published a Dutch-Malay dictionary, which included an appendix detailing his latest astronomical observations of the southern skies.56 His role in identifying twelve new southern constellations earned him a place of honor on one of the earliest celestial globes to picture the constellations. The 1603 globe issued by cartographer and publisher Willem Jansz Blaeu, who would later attain the post of official mapmaker to the VOC, included a dedicatory cartouche with de Houtman’s name.57 Clearly, de Houtman’s years of overseas service provided him with ample opportunities to enhance the reputation of the Dutch nation on the world stage, as well as to elevate his own status and renown.

Nevertheless, van der Haghen’s protest against de Houtman’s presence in View of Ambon elicited serious and sustained attention from Amsterdam’s often unmovable VOC directors. Their concern was so great that, in December 1620, they agreed to grant van der Haghen a meeting to settle the matter. At the meeting, it is recorded that van der Haghen submitted both a written complaint and his personal travel journals as evidence of his worthy service to the VOC. On December 30, 1620, the directors issued a striking decision. They conceded “that he [van der Haghen], at the expense of the Company shall have a similar map of the territory of Amboina made.” The directors approved the inclusion of a cartouche depicting his victory over four Portuguese galleons, which would serve “as a memory of the above-mentioned admiral,” as well as a “portrait with an inscription as having been the conqueror and the first governor of Amboina.”58 As both conqueror and first governor of Ambon, van der Haghen was assured a place in VOC history, though in a made-to-order map that, like View of Ambon, skillfully departed from historical fact.

Van der Haghen’s belated appointment to the post of governor of Ambon was perhaps a strategic public relations move on the part of the directors. At the time, the enormous financial costs of Governor-General Coen’s overseas military operations were of increasing concern to Amsterdam’s prominent company shareholders, who impatiently awaited large returns on their investments. Disgruntled shareholders asserted that the VOC must be an instrument of commerce, not conquest.59 The directors’ proposal for a new painting and inscription honoring van der Haghen’s fictitious governance would serve to retain the original painting’s emphasis on good administrative order in Ambon, at a time when war and conquest in the East Indies were unpopular with investors. Van der Haghen’s demand for self-representation would be met and his status enhanced. Or so it seemed.

Ultimately, the directors failed to keep their promise of producing a new painting. Buchelius’s journal entries concerning the lack of proper acknowledgment of van der Haghen continue for a full year after the December 1620 resolution. Writing at the turn of the eighteenth century, VOC lawyer Pieter van Dam maintained that no map bearing van der Haghen’s visage ever materialized, and he speculated that its production was impeded by other undocumented circumstances.60 Zandvliet writes that, although a revised View of Ambon was never made, the increasingly moderate political climate of the 1620s did lead to the erasure of laudatory inscriptions in the cartouches beside de Houtman’s portrait in the original View of Ambon.61 The whitewashed spaces today testify to the VOC’s willingness and power to face—or efface—its history.

Conclusion

That de Houtman, not van der Haghen, held his position as the public face of the VOC in View of Ambon testifies to the VOC directors’ power to write, revise, and rewrite the script of company history as it was unfolding. Indeed, van der Haghen would not be the only seafarer snubbed by the VOC. The remarkable overseas enterprises of Jacob le Maire, son of mutinous VOC shareholder and protester Isaac le Maire, would for years go without due pictorial recognition. This further demonstrates how much seventeenth-century Dutch seafarers stood to gain or lose depending on the company they kept.

In 1615, Isaac le Maire, recently ousted from the VOC’s administration for opposing the VOC’s profit-draining military operations and for divulging trade secrets to King Henry IV of France, financed and dispatched a rogue exploratory voyage. His son Jacob was at the helm. Jacob le Maire led his small fleet westward across the Atlantic, in search of a new route to the riches of the East Indies. Just south of the Strait of Magellan at the southernmost tip of South America, le Maire’s ships successfully navigated through a narrow, previously undiscovered and unnamed strait, now known as the Strait of le Maire. Continuing westward, le Maire safely arrived in VOC-administrated territory, though he and his crew were met with indignation rather than celebration. The then accountant-general and later governor-general Jan Pietersz Coen confiscated le Maire’s journals and held le Maire and his men captive. They were forced to return home on the next VOC return ship. Unfortunately, Jacob le Maire would not survive the trip.62

It was just shortly after his son Jacob’s death that Isaac le Maire was shocked to learn of an Amsterdam publisher’s plans to print and profit from an account of his son’s voyage. Publisher Willem Jansz Blaeu, maker of the 1603 celestial globe honoring de Houtman’s role in identifying new southern constellations, had somehow obtained Jacob’s journal from the VOC’s archives. Blaeu’s publication of the journal was ultimately blocked by legal challenges, but he was unwilling to disappoint a ready buying public. In 1618, Blaeu opted to publish the journal of Willem Schouten, a less controversial figure in the rogue fleet and a subsequent servant of the VOC.63

In the frontispiece image of Blaeu’s publication of Schouten’s journal, medallion-like portraits of circumnavigators Drake, Cavendish, van Noort, and Joris van Spilbergen flank the larger central figures of the composition (fig. 16). Willem Schouten assumes what was surely the rightful and central place of le Maire in the image. Posed behind a stone ledge in courtly attire, Schouten grips a pair of dividers. A winged Victory crowns him with a laurel wreath, while the legendary figure of Magellan looks on admiringly. Only after much legal wrangling did Isaac le Maire retrieve his son Jacob’s journals and see the due representation of his son in text and image. Four years after Blaeu’s publication, Amsterdam publisher Michiel Colijn issued Spieghel der Australische Navigatie (1622), which included a portrait of Jacob le Maire proudly holding a map that showed his discovery (fig. 17).64

Made-to-order and hung prominently next to the hearth in the Great Hall of Amsterdam’s Dutch East India House, View of Ambon offered itself for close inspection on the part of VOC administrators and distinguished visitors for more than a century. It invited viewers to methodically trace and retrace its cartographic contours and to read its surface like a document. In so doing, it came to embody VOC positions and practices abroad. The meticulously rendered particulars of Ambon’s geographic, political, military, and commercial situation certainly assured viewers that this critical trading post was closely observed, methodically mapped, scrupulously surveyed, and, most importantly, well administered by the VOC’s most perspicuous and dutiful servants.

Combining the matter-of-fact pictorial modes of cartography, perspective, and portraiture in a corporate gezicht, View of Ambon conveyed and consolidated the VOC’s public image of authority and legitimacy. In reality, however, the VOC’s first decades were turbulent. Around the time of the painting’s commission, the company’s profits were uncertain, and the directors’ capacities and willingness to generally represent the interests of shareholders and officers were unclear.65 The inclusion of Governor de Houtman’s portrait in View of Ambon invited viewers such as VOC lawyer Buchelius to reflect on the man—or men—who made this composite and corporate image possible. In his private journal entries, Buchelius accounts for the ways in which View of Ambon was, in fact, not the “perfect” and “skillful map” that the directors’ had commissioned.

The feud that ensued over proper representation in View of Ambon evidences the awareness among VOC officers of art’s role in both corporate and individual self-representation. This awareness was surely shaped by the precedents in print discussed in this essay. The Amsterdam directors’ willingness to hear and assuage van der Haghen’s demands for inclusion in View of Ambon and in VOC history demonstrates that, while the VOC securely held the territory of Ambon, its dominion in the realm of representation in Amsterdam was not complete. Additionally, it reveals the extent to which the VOC’s rigid and made-to-order pictorial conventions could be inflected to express divergent corporate and individual self-representations.

In the end, van der Haghen’s face-saving efforts were to no avail. De Houtman’s visage remained the face of the VOC, though View of Ambon’s empty cartouches conspicuously picture the company’s powers of effacement.