This essay reveals humor’s centrality and function in depictions of Saint Joseph from the fourteenth through the early sixteenth centuries, and it reconciles two strands of interpretation that have polarized the saint’s image into distinct early and late manifestations—one comical and derogatory and the other idealized. This faulty division is rooted in our misunderstandings of the reasoning behind—and the functions of—late medieval religious humor. Arguing for the influence of contemporary and earlier medieval satirical treatments of the fool, peasant, and unequal couple, as well as the role of laughter in veneration, the following offers an alternative to the theory of education as the sole explanation for humor’s presence in religious imagery. It encourages a more nuanced understanding of images used for private and public veneration, acknowledging not only the presence but also the purpose of visual jokes in such works.

The period of transition bridging the late Middle Ages with the Renaissance reveals a fascinating moment in Christianity’s past, one for which humor and satire were very much relevant, and even beneficial. Although theological and ecclesiastical history does not divulge much about the function of satire in religious veneration, surviving art, legends, hymns, and plays tell a different story. A case in point is Saint Joseph of Nazareth, whose popularity as an object of veneration rose exponentially between ca. 1300 and 1600, while artists and patrons produced and consumed devotional images that sometimes highlighted the hilarity of the saint’s circumstances with surprising verve. This material evidence shows us that for his early modern devotees Joseph could be, simultaneously, a beloved, revered, venerated, and hilariously ridiculous figure. Because of our distance from medieval and Renaissance humor (and often because of our eager separation of the early modern from the medieval),1 it is exceedingly difficult to imagine a devotee laughing at and venerating a saint at the same time. But humor, laughter, and the religious experience must be conceptualized according to the cultures under study and not today’s experiences. Artworks from the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries reveal how religious experiences, humor, play, and laughter could be intertwined, sometimes in ways that defy modern logic and rationalization. An iconographic approach, based upon Erwin Panofsky’s principles of iconographic and iconological interpretation,2 is necessary to understand Joseph’s humor in art. But this essay offers an alternative to interpretations of northern Renaissance art as solely visualizing the theologically complex, as oriented toward the intellectual and aesthetical elite. Rather, depictions of Joseph are considered in relation to their associated “popular” productions and beliefs,3 an approach, I argue, that does not counter the theological richness of many works but instead amplifies it.

Art and texts that existed outside of the official support and sphere of the papacy not only reveal the strength of Joseph’s cult as early as the thirteenth century, but they also allow us to reconcile two strands of interpretation that have polarized the saint into distinct early and late manifestations, one comical and derogatory and the other idealized. From about 1300 through the sixteenth century, depictions of Saint Joseph attest to the humorous and bawdy as inextricable parts of the saint’s cult, even as he came to be taken more seriously as an object of popular devotion. But scholars of the saint’s history, and of early modern history in general, have often treated the power and purposes of humor too categorically, seeing no accord between the saint’s humorous representations and his role as exemplar; he becomes therefore either a figure of pure derision or one completely devoid of humor. Laughter and the bawdy—considered in prior scholarship to constitute merely “low” culture—have been too often deemed appropriate to the laity and irrelevant to the sacred.

Scholarship about Joseph’s rise through the efforts of elite ecclesiasts alone has created an image of a saint who, throughout most of the Middle Ages, was viewed solely as a subordinate and comical figure.4 His perceived marginalization before the Counter-Reformation is predicated upon the assumption that any humorous depiction of the saint was intended only to be deprecatory. Johan Huizinga’s The Autumn of the Middle Ages, first published in English in 1924, contends that the late fourteenth- and fifteenth-century veneration of the saint was more “subject to the influences of popular fancy rather than of theology.”5 Huizinga includes three poems that he interprets as entirely irreverent toward the saint, characterizing him as ridiculous and foolish. Louis Réau likewise falls into the trap of total derision, claiming that the verses of the French poet Eustache Deschamps (1346–1406) indicate that Joseph, “le rassoté (the fool or the weary),” had little respect in the late Middle Ages and that a major change in how Joseph was perceived only took place in the seventeenth century, with the saint marginally significant until then.6

But the depictions that angered the French theologian Jean Gerson (1363–1429)7 for their characterization of the saint as a doddering old fool are perhaps not only deprecations but also celebrations of the comedy of his circumstances, and even a form of veneration. Because late medieval theologians attempted to suppress this cultural production by relegating it to the realm of the sacrilegious, the flowering of Joseph’s cult is thought not have occurred until the late fifteenth century,8 and then only as a result of the efforts of Gerson’s earliest theological texts in praise of the saint, requesting the establishment of the Feast of the Engagement of Joseph at the Council of Constance (1414–18). But veneration of Joseph had already begun to increase in the twelfth century, fostered by a contemporaneous rise in devotion to the Virgin Mary. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) provides one of the earliest expositions on Joseph’s importance in his Advent Homily on the Missus Est, extolling the saint’s virtues as a descendant of the house of David and the protector/nourisher of Christ.9

In 1489, Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) composed a treatise entitled De Laudibus S. Josephi.10 The campaigns of these late medieval theologians, including Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly (1351–1420), finally culminated in the official ecclesiastical establishment of the saint’s cult in 1479, with the introduction of Joseph’s feast day on March 19 into the liturgy of the Catholic Church under the Franciscan pope Sixtus IV (1471–1484). The feast was not fully authorized, however, until the sixteenth century.11 By the end of the seventeenth century, Joseph had become one of the most venerated saints of the Catholic Church.12

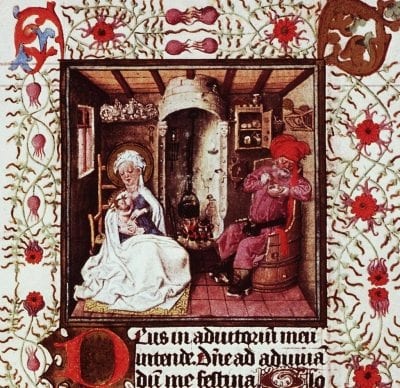

Scholars like Carolyn C. Wilson, Sheila Schwartz, and Pamela Sheingorn have contributed a crucial corrective to interpretations of Joseph’s depiction and cult that focused exclusively on the derision directed at him. Wilson’s St. Joseph in Italian Renaissance Art and Society aims to “dispense at last with the seemingly compulsory repetition of the notions that St. Joseph’s cult either did not exist during the Renaissance or was merely a local phenomenon and that Joseph was typically portrayed as a figure of no consequence or of derision.”13 Her discussion of northern images, however, attempts to cleanse Joseph of his humor, stressing the necessity of rethinking “any modern assumption of an artist’s intent to ridicule Joseph in scenes that portray the saint cooking or performing other charitable and parental acts.”14 Sheila Schwartz’s work likewise sanitizes Josephine imagery that is clearly not without humor. She argues that Conrad von Soest’s Wildunger Altar of 1403 “disproves a demeaning intent in the artist’s presentation of Joseph, for in the [Adoration] scene, Joseph stands reverently behind the Virgin as the Magi adore the Child.”15 But her example itself demonstrates the possibility of Joseph appearing as a comical, beloved, and venerated saint all at once on a high altarpiece. Joseph’s animalized depiction in the Nativity scene—crouching on all fours before a cooking pot (fig. 1)—is probably not a humble enactment of Byzantine proskynesis, the act of prostrating oneself before a ruler, as Schwartz suggests.16 Such arguments often discount the widespread influence of popular literature and thought within late medieval religious culture. Schwartz concedes that Joseph functioned as a base figure of ridicule in German Nativity plays, but her assertion that such “coarse entertainment for the lower classes that flourished in the absence of a strong ecclesiastical authority . . . exerted no influence upon the higher levels of literature and art,”17 must be incorrect, for humor appears even in devotional works executed for the Burgundian Duke Philip the Bold (r. 1363–1404) and his circle.

Joseph is primarily studied as a Counter-Reformation saint who only began to rise in public esteem during the Renaissance because of Church doctrine and theological writings. Outside of the official lines of discourse, however, Joseph’s cult probably had a strong following by the early thirteenth century, the approximate date of the appearance of the saint’s most important relic at Aachen Cathedral: the saint’s Hosen, variously translated in text and image as stockings, pants, or even boots, and believed to have been the swaddling clothes of Christ. The earliest fixed date tied to the relic is its placement in the Marian shrine of Aachen Cathedral in 1238–39.18 The widespread fame of the relic has been largely ignored in Joseph studies, although it reportedly was visited frequently by pilgrims after its appearance at the cathedral. Various mystical writings, Christmas hymns, and fourteenth- through sixteenth-century chronicles mention the holy Hosen themselves and their exhibition at Aachen, and they appear also on several pilgrim flasks and medallions.19 Beginning in 1349, the four great holy relics of Aachen—the swaddling clothes/stockings of Joseph, the tunic Mary wore when Christ was born, the loincloth of Christ, and the shroud of John the Baptist—were all displayed in the cathedral during the “great pilgrimage,” which took place every seven years.

Because the relic was believed to have been sewn from Joseph’s stockings, it became the epicenter of a large oral and visual tradition that celebrated the saint’s care for the Christ Child in the face of destitution, while often poking fun at the man for losing his pants. In addition to drawing hordes of pilgrims to Aachen’s cathedral, the story of Joseph relinquishing his clothes inspired raucous scenes in cradle plays (Kindelwiegenspiele), Nativity plays that share the central motif of Joseph rocking the cradle and singing to the baby.20 The doddering character of Joseph in these plays is most often interpreted as pure debasement for the purpose of comic relief, but the more recent readings of Rosemary Hale, Stephen Wright, and Pamela Sheingorn have demonstrated that the inherent comedy could have served a higher purpose.21 In the Hessische Weihnachtsspiel of Friedberg, dated between 1450 and 1460, in a nod to the famous Aachen relic, an impoverished Joseph sacrifices his old, worn stockings to swaddle the Christ Child. He then proceeds barelegged to an inn to solicit help with the cooking of the baby’s porridge. He meets the maids Hillegart and Gutte there, who scorn him, demanding, “What do you want, old goat-beard?”22 Hillegart and Gutte then begin to beat the old, barelegged Joseph. After this initial confrontation, however, it is Joseph who ultimately mediates a second fight between the two kitchen maids, and as a result, he, the two women, and their landlords enthusiastically direct their attention to singing, leaping about, and rocking the cradle, an action derived from the liturgical origins of the Kindelwiegenspiele.23 He therefore serves as an important “bridge to the act of joyous worship within the drama,”24 and as Wright indicates, the very fact that it is the chorus of Jews and the kitchen and nursemaids who chastise Joseph for his inabilities should indicate that the audience was fundamentally on his side. 25

From the very beginning, therefore, Joseph’s rise in importance as a figure of veneration was tied to the laughter he elicited in hymns, plays, and art as the well-meaning but unenlightened old fool. This is precisely why Joseph’s early modern history remains so controversial and misunderstood; his earliest veneration was steeped in humor, which continued through the Renaissance. The impact of humor and of the Hosen seems most prevalent in the art and texts of Germany but is strong in the Low Countries and France as well, and particularly in regions in closer geographical proximity to Aachen. Perhaps our difficulty in acknowledging that medieval and Renaissance artists, patrons, and viewers could have revered a saint whom they sometimes ridiculed stems from our familiarity with today’s more sober understandings of the Catholic saints, which arose out of the Counter-Reformation.

But while it is true that Western Europe was hegemonically Catholic and believed in the importance of saints as tangible manifestations of God’s presence and favor, for many devotees, there existed no problem with laughing at a saint like Joseph. Laughter might be understood as a method of venerating him, while acknowledging his faulty humanity. His sometimes comical faults were, for many, what made him most important as the head of his holy family, for Christian belief taught that the saint was biblically cuckolded by God Himself, and at a very old age, unequally paired with a very young, pregnant, and intangibly holy virgin (a fact that was also satirized). In the Bible he does not fully understand the importance of his role—he remains dumbfounded—until after the child is born. Joseph’s lack of enlightenment, his old age, his concern for the mere worldly details of caring for his family in the only ways he knows how, recounted in legends, stories, plays, and hymns—these were readily humorous to an audience familiar with the challenges of parenting and surviving in a difficult world. But Joseph’s “imperfections” were at once his doctrinal perfections. He needed to be old and chaste, so that Mary might remain pure in the eyes of all. And Joseph’s delayed enlightenment regarding the importance of his foster son may have allowed medieval and early modern Christians to relate to him in a way they rarely could with other saints, for they, too, remained in search of enlightenment as followers of the Church and its mysteries.

What we know of late medieval devotion suggests that laughter and play could have naturally influenced the fabrication and experience of sacred art. Many have questioned the assumption that the presentation of symbolic meaning through recondite symbols was considered the most important artistic achievement of art during this period.26 Period discussions of devotional works of art in fact focus on how an image works in relation to the beholder, rather than what it depicts specifically. Narratives of Christ’s life and devotional handbooks reveal this shift in interest from the theologically recondite to personal practice, particularly in visualizing one’s own personal response to religious events.27 Sixten Ringbom related this visionary tendency in the late medieval religious experience to images, arguing that such experiences sought primarily to commune, in a very visceral and direct manner, with Christ and the saints in their most humanized form. Art could stimulate this sense of personal engagement in a number of ways. Illusionistic art—that which could “eradicate or deny the distinction between the painted image and that which it represents”28—could establish a tangible connection between the beholder and the divine subject. This intensity of experience is what Ringbom describes as the “empathic approach” to image theology, which is not guided by a need for edification or adoration alone, but by a “deep emotional experience.”29

The viewer’s experience of sanctity in art was therefore not focused upon the mere search for “concealed” theologically complex symbolism. Much of the symbolism that is so recondite to the modern viewer was probably common knowledge for much of the laity, varying, of course, according to their social standing and associated level of education.30 Historical analyses of religious life indicate that the laity were more interested in trying “to ‘see’ the consecrated host as a vision of the Christ Child, and going on both real and imaginary pilgrimages and processions, mingling superstition and personal desires with more officially recognized activities.”31 The humanization of Joseph, even in his most playful or bawdy forms, is directly symptomatic of this desire for direct contact with the Holy Family.

The Influence of Secular Satire

A small, painted wooden panel from a Mosan (or South Netherlandish) tabernacle of ca. 1400 (fig. 2) presents a blatantly humorous image of the old father in its scene of the Flight into Egypt. At first glance it appears that the artist compressed the composition so much that Joseph’s head was overtaken by the ass’s ears; of course, the artist certainly could have instead raised the terrain of the right-hand side to present the saint’s face more clearly. The image is probably nothing less than a demonstration of satirical humor at its finest, comparing the poor, weary foster father with the ass, and thus with the popular contemporary type of the fool with his ass’s ears, in contrast to the youthful perfection of his wife. A similar visual play appears in an Adoration of the Magi by the Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece of ca. 1500 (fig. 3), a seemingly innocent juxtaposition, until we place it within the wider context of contemporary artistic and literary treatments of derided characters. These reveal just how popular and clear the risible meaning of such a comparison between beast and human could be for an early modern audience. The conspicuous prominence of the ass’s ears near Joseph can be understood as an unequivocal reference to foolishness, a form of mockery. The most common characteristic of the ridiculed country bumpkin in late medieval society was his affinity to animals like the ass, both in terms of physical appearance and morals. French fabliaux and German Schwankliteratur characterized peasants, for example, as easily tricked and cuckolded because of their bestial stupidity.32 German literature before 1400 tended to describe rustics as boorish or exhibiting uninhibited, animalistic, and frenzied behavior, while the peasant was depicted in art in a variety of ways, as Paul Freedman has shown, some “as a familiar subordinate, lowly in a normal way, perhaps ill-dressed, bent over, or dark . . . while others . . . [are rendered] as a disturbing inhabitant of a world apart, [often] subhuman.”33 In any of these cases they could be presented as animals. But the draft animal, and especially the donkey, was the most common selection for the less threatening, yet still ridiculous, toiling peasant—the one who knows his place.34 Strong visual links between Joseph and the ass and ox of the Nativity, as well as the donkey in Flight into Egypt scenes (which were relatively uncommon on altarpieces before the late fourteenth century), emerge out of this preexisting tradition of peasant imagery.

The characteristics for which peasants, rustics, and fools were ridiculed during this period included bestial stupidity and intemperance with drink and food. It cannot be pure coincidence that these very traits colored many depictions of Saint Joseph, although his character may, as in the Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece’s Adoration, be dignified in the same image. By the fourteenth century, the theme of the raucous peasant wedding had already been established,35 although many of its characteristics, such as the parallels between the behavior of the unruly, gluttonous peasants with their beasts of burden had appeared earlier in thirteenth-century manner books.36 By the fifteenth-century, carnival plays like the German Fastnachtspiele, which attend to bad manners, sexual and scatological offenses, and deformity and ugliness, were already an established form of humorous entertainment as well.37 By the second half of the fifteenth and the early sixteenth centuries, although rustics were derided in prints and paintings for the same bestial qualities as they were in earlier images, extreme exaggeration frequently rendered their debasement even more explicit. Even members of the bourgeoisie could become implicated in the lack of decorum38. The rise of an art market for broadsheets, prints, and paintings that ridiculed character types, including the peasant, the poor, the vagabond, the profligate, the miser, the money-changer, and the hen-pecked husband, documents the extent to which an interest in humorous types also permeated the burgher classes. In addition to the popular satirizing of peasants, rogues, Jews, Landesknechten, artisans, and innkeepers, no authoritative figure was safe from ridicule, including the priest, noble, and merchant. Jörg Wickram’s charming tale of the monk who brayed like an ass makes this apparent:

In Poppenried there lived a monk, who oversaw its parish. He had an exceedingly abrasive voice; when he stood on the pulpit, whoever had not heard him before thought he had lost his senses. One day he had been crying out rather pitiably when a godly old widow in the church beat her hands firmly together and wept bitterly; the monk observed this well. After the sermon was finished, the monk asked the woman what had moved her to such devotion. “Oh dear sir,” she said, “my beloved, deceased husband, as he parted from this life, knew well that I must share his goods and property with his relatives; therefore he bequeathed me in advance a handsome young ass. But not very long after my blessed husband’s death, the ass died too. This morning, as you began to cry out on the pulpit with such a great and painful voice, you reminded me of my darling ass; he had rather the same voice as you.” The monk, who himself had expected a kind compliment from the old woman, or a praise greater than that of which he was worthy, found a disdainful answer, just like her comparison between himself and an ass. Thus it befalls in common all those greedy for commendation; when they think to obtain great praise, sometimes the greatest of mockeries comes instead.39

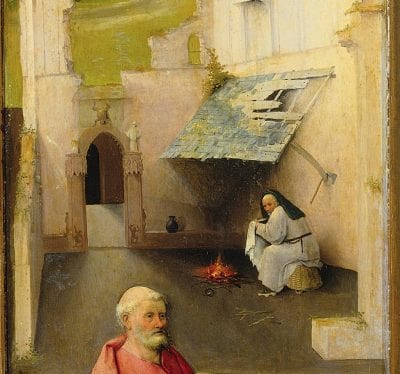

For someone exposed to the visual and literary language of derision, an audience that grew especially large in the fifteenth century with the circulation of cheaper, mass-produced satirical prints and broadsheets, the humor of Joseph’s comparison to the ass would probably have been explicit. A number of depictions affiliate Joseph with his bestial companions in ways both overt and implied. These include the Hamburg Altarpiece of Saint Peter by Master Bertram (fig. 4), in which Joseph appears to tear into a wineskin or piece of bread with his visibly protruding front teeth.40 His portrayal on the same diagonal, performing the same action, teeth bared, as the ass in the lower left corner hints toward derision.41 Like the Christ Child at Mary’s breast, the two are feeding in what appears to be a charming familial scene. Nevertheless, careful examination of the composition reveals that the baby looks toward Joseph, while Mary casts her eye toward the dull beast below, who mirrors the behavior of her less gracefully portrayed, self-nourishing husband. The common visual parallel of Joseph with the ass, as well as the ox, is likewise apparent in an Adoration of the Magi by the Boucicaut Master and his workshop (fig. 5), in which a seemingly perplexed Joseph, an ass, and an ox lean over the shed’s wooden fence to view the baby. And a German Adoration of the Magi from ca. 1525 (fig. 6) appears to play upon Joseph’s “horned” status as cuckold. An Adoration of the Magi by the Master of the Legend of Saint Barbara (fig. 7) presents, in pose and action, a complementary vision of bent-over saint and ass.

Artists often render the parallels between ass and saint through compositional construction, but these are most clear when the two exhibit similar behavior. Depictions of an ungraceful, self-nourishing or “guzzling” Joseph abound in early Netherlandish, German, and French art, as in Veit Stoss’s Flight into Egypt scene (fig. 8) from the high altarpiece of Bamberg Cathedral and a Flight into Egypt scene from the Buxtehude Petri-Altar (fig. 9), executed by Meister Bertram’s workshop. Again, the visual vocabulary of these presentations derives from the base behavior of the animal-like rustic. A painting of the Rest on the Flight into Egypt of ca. 1500 by a follower of Martin Schongauer (fig. 10) presents a fumbling Saint Joseph and the ass in true bestial fashion. Their facial expressions, both with mouths open and a dumb, uncomprehending stare, probably did not fail to amuse, since the depiction of an open mouth with exposed teeth was considered particularly demonstrative of baseness, as suggested by both physiognomic thought and standards of behavioral conduct outlined by popular thirteenth-century books of manners.42 In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, one’s external appearance was still believed to correspond to inner character, with physiognomy determined by one’s astrological horoscope. If a person’s features were imperfect, this indicated an inclination toward specific vices, which one could succeed in resisting, if virtuous enough.43 This medieval understanding of physiognomy was closely related to the classical one, with physicians often well versed in the Aristotelian thought found in popular scientific physiognomies.44 The anonymous Aristotelian treatise Physiognômonika from the third century BCE supports the interrelatedness of appearance, inner character, and status, as do the Pardoner’s, Reeve’s, and Miller’s Tales of Chaucer, revealing the widespread late medieval popularity of such “medical” thought.

Josephine humor could function as something more than merely derisive joke making. Often interpreted as a space-filling device,45 or “an afterthought,”46 the humor of Joseph’s rusticity overshadows his prominence in many interpretations. Ruth Mellinkoff notes that “an excessive love of drink was attributed to Joseph and elaborated in some of the German dramas, and it is sometimes reflected in the visual arts,”47 and describes the Buxtehude Petri-Altar’s Joseph as “a peasant boor who drinks too much.”48 But the image of Joseph “guzzling” is an important motif in the aforementioned cradle plays. Toward the end of the Schwäbisches Weihnachtsspiel, when Mary asks Joseph to take her and Jesus to Egypt, Joseph replies:

Maria, I will do that very gladly, for your child gives a very good reward. And so I will put the cradle upon my back, but it will weigh me down quite heavily. And I’ll wash my old windpipe with a drink from my bottle.49

In the Ludus in cunabilis Christi, which forms part of the Erlauer Weihnachtsspiel, Joseph also drinks and offers wine to visitors, Mary, the midwife, and even the child, to help him sleep.50 In the Sterzinger Weihnachtsspiel, Joseph himself drinks frequently and offers the midwife wine —“gueth wein, dapey magstu woll frelich sein.”51 In addition to equating Joseph’s behavior with that of the uncouth, intemperate, animal-like rustic, these medieval plays also make clear that Joseph’s drinking and conviviality are implicit in his important role as the faulty, yet well-intentioned caretaker of Christ and Mary.52 He is not only a drinker but also a devoted father, provider, and host, and in these characteristics he is a model of familial love and responsibility.

The medieval understanding of poor, old Saint Joseph’s purity, and the incongruity of his marriage to a teenage wife who is carrying a child that is not his own but rather that of the omnipotent Father, resulted as well in a variety of comic depictions. The centrality of the erotic and bawdy in late medieval comic art and literature is overwhelming by today’s standards, frequently occupying what many today would consider the realm of base or “low” humor. Yet the recurrence of bawdy jokes in prints appealed to the moneyed classes who collected such objects. The jokes and puns that appeared in these images, as well as in the comic tales of the time, could have easily shared features with artistic creations that made fun of Joseph’s cuckoldry and old age, particularly in juxtaposing his bumbling, foolish nature against that of his young, pregnant, divinely elevated wife. The juxtaposition of such “unequal couples” was itself a highly popular theme in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century prints and paintings,53 so we should look also to this trend to understand the humor of these depictions of the Holy Family.54

The theme of the unequal couple allowed for ample visual ingenuity in mocking the type of the old, impotent cuckold who marries or lusts after a young girl. Even as the truth of Joseph’s unequal marriage remained central to Christian theology and devotion, sacred scenes of the prototypical unequal couple were not at all divorced from the profanity of popular carnival plays, stories, tales, and secular art dealing with ill-matched pairs, which flourished particularly from around 1470 to 1535. An intensified fifteenth-century focus on domestic scenes of the Holy Family that facilitated the engagement of the beholder probably in turn spurred the popularity of such profane equivalents. The theme of the old cuckold and fool paired with or tricked by the young beauty, however, finds its roots as early as the third century BCE in the comedies of the Roman poet Plautus (ca. 251–184 BCE) and emerges throughout the Middle Ages in such works as the twelfth-century short poems of Marie de France and the thirteenth-century Roman de la Rose (begun ca. 1237). From the second half of the thirteenth century, Franciscans and Dominicans used moralizing exempla in their sermons that mocked and warned against marrying old men and women for money. Fourteenth-century sources like Boccaccio’s Decameron (begun ca. 1350), Netherlandish farcical sotternieën (Feasts of Fools), Chaucer’s “Merchant’s Tale” (begun 1386–89), and Miroir de Mariage by Eustache Deschamps (d. 1406?) all engage with the theme, as do fifteenth-century German manuscripts and carnival plays like Vom Heiraten Spil. Boccaccio’s Ameto tells the story of the young Agapes, whose marriage to a repulsive old man (rife with snoring and impotent lovemaking) drives her to seek her pleasure with a handsome younger rival. Von einem plinten, dated to ca. 1425–76 and sharing its sources with Boccaccio and Chaucer, tells of how an old blind man’s young wife climbs into a fruit tree with her young male friend, whom she enjoys while her husband wraps his arms around the trunk, thinking he is preventing the young man from climbing up. All of a sudden Saint Peter and Jesus walk by and decide to restore the old man’s sight, forcing the wife to explain herself. But the old cuckold’s stupidity saves the day, since he gratefully accepts her tale that her only intention had been to restore her husband’s vision.55

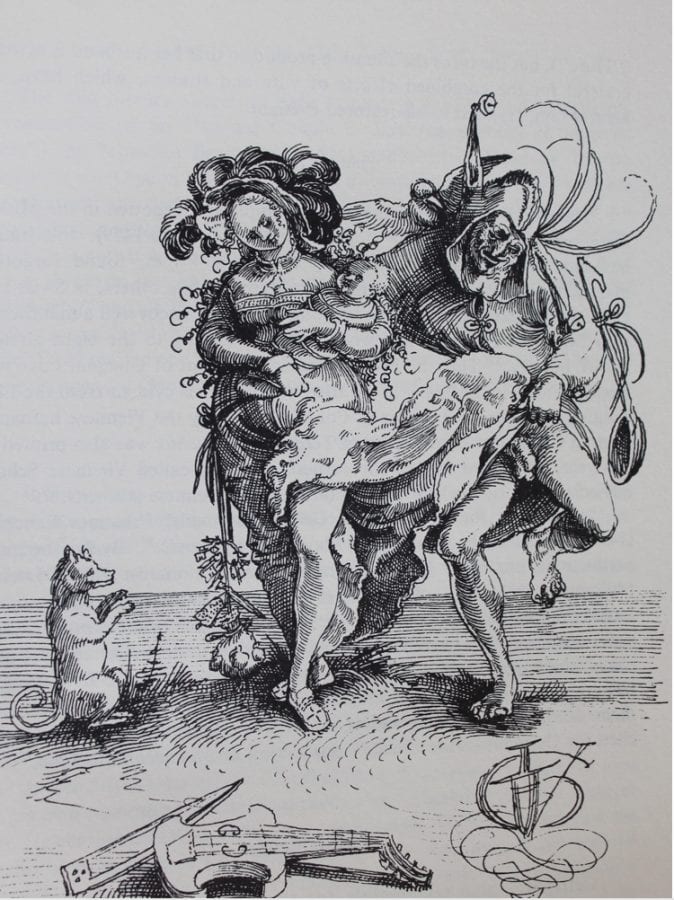

Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools (1494), Erasmus’s Praise of Folly (1509), and Hans Sachs’s poems and plays from the first half of the sixteenth century all include sets of unequal couples, and all incorporate the figure of the fool from fifteenth- and sixteenth-century moralizing tales, plays, and folk festivals like the Netherlandish sotternieën that mock such ill-matched pairs.56 In Sachs’s poem “Zweierlei Ungleiche Ehen,” written in 1533, a young woman encourages the lust of an old man in order to gain his money. He, like so many other old people in Sachs’s work, wears a fool’s cap with ass’s ears to signify his stupidity. Urs Graf’s drawing (fig. 11) depicts the often recounted theme, with the old pant-less fool with his ass’s ears being a telling exaggeration of one of Joseph’s most frequently depicted comical attributes, the holy stockings, depicted in a devotional polyptych commissioned by Philip the Bold (fig. 12). The iconographic pairing of the old man and young woman appears as early as the fourteenth century in English and Franco-Flemish manuscripts, while the medieval tale of Phyllis riding Aristotle became a popular theme on early fourteenth-century French ivories, and in later prints as well. Mid-fifteenth-century engravings and drypoints by the Master E.S. (active 1450–1467), the Housebook Master (active ca. 1470–1500), and Israhel van Meckenem (ca. 1440/45–1503) satirize such pairings (fig. 13), while sixteenth-century prints and paintings took up the theme with fervor; an early sixteenth-century etching by Lucas van Leyden depicts an old fool with a sagging purse embracing the young object of his affections.57 Such images and tales enliven our understanding of Joseph’s own endowments and their positioning in sacred iconography.

The strength of late medieval bawdy humor appears, for instance, in the Master of the Saint Barbara Legend’s Adoration (see fig. 7), in which Joseph drills persistently into the makings of a mousetrap. This lay not in a situation’s sexualization but in the success of what Howard Bloch defines as a linguistic substitution or deflection, in this case made visual. The highest form of eroticism in the highly popular fabliaux and other comic tales tends to arise from “a profuse celebration of the body, and especially of the sexual organs.”58 Most often “naughty” body parts are discussed using euphemisms that are quite frank, such as the “tool” worn by the apprentice of a blacksmith. The example of the purse (bourse) as a metaphor for the male genitalia is particularly common, not only in word but also in images, as in the miniature of January in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (fig. 14).59 The expressions “to hammer,” “to pierce or penetrate,” and “to pound or strike a blow” are among the most frequent figurative expressions used in the discussion of sex. In the Master of the Saint Barbara Legend’s Adoration scene, the old man’s persistent drilling away at a passive piece of wood (perhaps in an attempt to trap the elusive furry “mouse,” the linguistic substitution for “vagina”) could have easily been understood as funny by its contemporaries, who were mostly well versed in such popular word play, as Louise Vasvari points out.60

Like the mouse/vagina trap, the “tool” and “stick” are readily taken up in images of Joseph the carpenter at work that also mock his lack of sexual prowess as an old and chaste cuckold living with his beautiful young wife. In the Hoogstraten Joseph’s Repentance of His Doubt (fig. 15) from a series on the saint’s life, thought to be a copy of Robert Campin’s lost Life of Saint Joseph of ca. 1425, the saint kneels before his pregnant wife, surrounded by an overflowing pile of useless oversized tools. His pouch, tools, knife, and sword are presented rather limply in another depiction, The Doubt of Joseph in the Musée de l’Oeuvre Notre Dame of Strasbourg (fig. 16),61 with the exception of a single stout knife that protrudes from the dense, unyielding wood of the table that divides the old man from his young wife. The Strasbourg Doubt of Joseph is rather reminiscent of contemporary prints satirizing the young sword-wielding dandy’s advances on the chaste knitting girl whose cat rests conspicuously near her ring-shaped basket of yarn. An example is Israhel van Meckenem’s Visit to the Spinner (fig. 17) from his Scenes of Daily Life engravings, dated ca. 1495-1500. The young dandy’s phallic sword is notably larger than poor Joseph’s diminutive knife.

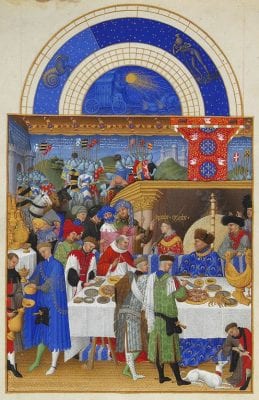

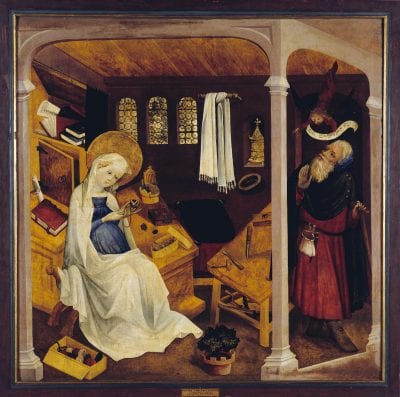

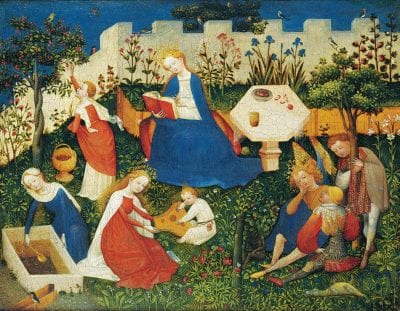

The Strasbourg Doubt of Joseph has been attributed to the Master of the Little Garden of Paradise, also known as the Upper Rhenish Master, and the painter of the Frankfurt Städel Museum’s charmingly diminutive garden scene of Mary and Jesus surrounded by saints and their various attributes (fig. 18). Humor and play are prevalent, and sometimes irreverent, throughout this tiny devotional panel. Saint George’s dragon lies prostrate and belly-up in the sun, while Saint Michael’s chained-up ape/devil glares boldly at his master, the bored courtier, who chats lackadaisically with a third saint (presumably Sebastian), who nonchalantly wraps his arms around a tree. The artist blends the humor and charm of more secularized gardens depicting the romping nobility with a devotional scene of Mary and Christ in the hortus conclusus, a kind of fusion of sacred and chivalric themes that mirrors the meeting of veneration with humor in many depictions of Joseph. The link between the Little Garden of Paradise panel and the Doubt of Joseph is likewise evident through the artist’s inclusion of a tiny potted bush reminiscent of a walled garden in the Strasbourg scene, certainly a symbol of (or play on) Mary’s virginity. Despite what some might consider the crudeness of these humorous visual puns, jokes on the impotency of Joseph could be simultaneously charming, as in the Holy Family at Supper miniature from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves (fig. 19), in which Joseph’s “dagger and pouch” lies uselessly limp, in contrast to those of the phallic cupbearers in the January miniature of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (see fig. 14).62

Laughter as Veneration

Of the scholars who note the inherent comical nature of much of Joseph’s Renaissance iconography, only two have accepted its potential ability to mirror the saint’s importance for the history of salvation. Louise Vasvari first pointed out that visual puns on Joseph’s cuckoldry are sometimes present in images of the saint that have been interpreted as theologically rich in symbolism. To explain her astute observations on the sexualization in the Mérode Altarpiece, however, she makes a distinction between medieval clerical culture and what she calls the “popular-oral consciousness of lay religiosity,”63 which probably was not so distinct during the late medieval period—for what would preclude the clergy from laughing at cuckoldry? As if to excuse her excellent arguments, which could be perceived as “sacrilegious,” she writes that “the fifteenth century Joseph was as yet very far from achieving sainthood.”64 This was not the case, however, considering the extensive evidence of pilgrimages to Aachen to see the Hosen, as well as the already well-established oral and visual culture surrounding that relic.

Francesca Alberti’s essay on the “divine cuckolds” Saint Joseph and Vulcan underscores Vasvari’s contributions and notes that “the comic persona of Joseph played an important role in the theology of Incarnation as it was able to communicate basic doctrine to a large public that was not particularly acquainted with religious matters.”65 But the issue of Mary’s pregnancy by God and Joseph’s foster-paternity was known by all viewers—jokes on his cuckoldry could not have functioned for the purpose of enlightening an uneducated public. Furthermore, many of the images that satirize Joseph’s role were created for the personal devotion of the educated elite of the early modern world. Perhaps most importantly, this hypothesized uneducated public was probably far more educated on religious matters than the majority of today’s Christians, as Carol Purtle has pointed out.66

While Alberti rightly acknowledges the presence of a potential function for humor in a religious image, she notes that “a derogatory allusion to the satirical tradition of the willing cuckold . . . would certainly not have been appropriate for a saint.”67 Yet many representations of the saint evoke contemporary derogatory secular and profane prints, paintings, and tales, often focusing on cuckoldry, while pant-less Josephs (see fig. 12) and diaper-drying Josephs (fig. 20) suggest a link to popular preoccupations with gender relationships, which take shape in “battle for the pants” imagery that mocks subservient husbands (fig. 21). Josephs who clutch and ogle golden treasures poke fun at the Christian caricature of the miserly Jew, while simultaneously evoking the importance of personal profit for the nuclear family, an idea echoed in Saint Bernardino of Siena’s sermons on the importance of Joseph’s role as financial head of his family.68

Instead of looking toward education as an explanation of humor’s function in early modern Josephine imagery, or shying away from acknowledging satire’s influence, one context that we should first consider lies in the preceding medieval trend of “play in the margins.” This took shape in the form of visual puns that first graced the column capitals, walls, misericords, and exteriors of great cathedrals and proliferated throughout religious books. The idea that the humor of contemporary jokes and satirical prints, panels, plays, and tales would infuse religious representations of Saint Joseph accords with an already existent and strong medieval trend of holy laughter on the margins, which Keith Moxey argues influenced Hieronymus Bosch and “the humanist artist’s new claim to artistic freedom.”69 This trend can help us understand the centrality of humor as well as its possible function in Renaissance religious imagery and how humor transcended such categories as sacred and secular, or lay and clerical.

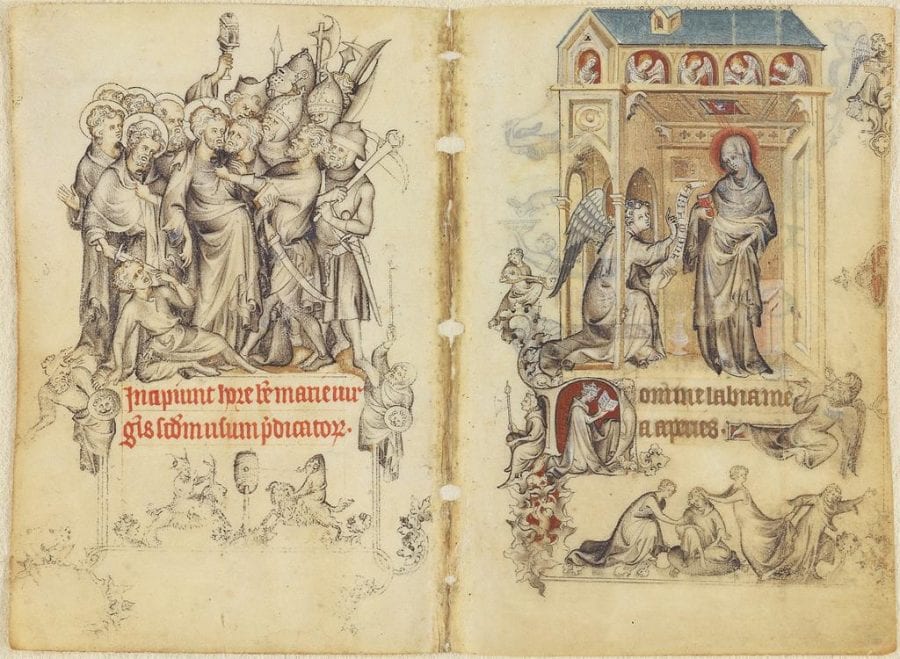

Of interest here is the interaction between what today we would consider irreverent commentary in the margins of manuscripts or church buildings and the sacred events depicted at center stage. Michael Camille revealed for us this interaction of the margins with the center, not just in terms of their meaning, as Lilian Randall has successfully established, but with respect to the margin’s function in conveying meaning for the whole. The center, Camille wrote, is dependent upon the margins for its existence because “things written or drawn in the margins add an extra dimension, a supplement, that is able to gloss, parody, modernize and problematize the text’s authority while never totally undermining it.”70 Courtly conventions like the service of ladies were satirized in the margins of manuscripts as well, with the marginalia of romances often being self-referential, functioning as a spectacle for the delight of the courtly viewer, while satirizing the social practices of the aristocracy. By interpreting marginal and monstrous forms as crucial to the visual product as a whole, Camille adduced the images’ ability to convey meaning to both lay and clerical viewers simultaneously.

In his discussion of a procession of monstrous creatures on the south door of the church of Saint Pierre at Aulnay-de-Saintonge, Camille drew an important distinction between “ambiguity” and the “ambivalent”: “while ambiguous things cannot be defined in terms of any specific category, things that are ambivalent belong to more than one domain at a time.”71 The marginal imagery in monastic foundations and cathedrals therefore existed in two interpretive spaces, but according to this reading, they do not overlap. For the monks at Aulnay, the violent and greedy procession over the south door could have signified the vulgar rabble of the illiterate layfolk traveling on pilgrimage. But for the laity, the same images, particularly the ram-bishop and harp-playing ass, served to critique clerical greed and illiteracy.72 This ambivalence is latent in many of the images that adorn churches, altarpieces, paintings, and manuscripts—any of the spaces in which sacred and secular concerns intertwined in the late Middle Ages—and this phenomenon was a constant for any God-fearing individual. But the realm of the ram-bishop, for example, may be extended beyond lay interpretation alone. A critique of greed within the church would have been just as poignant for a lesser cleric; throughout the Middle Ages the ecclesiastical elite were criticized in literature written by and for the clergy in Latin, a language few laymen could read at the time.73

Humor and satire could be present in works that reflect sincere devotion, as in the Betrayal and Annunciation miniatures of the Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux (fig. 22), in which the bas-de-page includes a bawdy mock-joust with the participants mounted on goats, the object of which is to “pierce the barrel” in the center, a visual pun on the vagina or womb.74 The expression, “aforer le tonel a quelqu’une (to broach someone’s barrel),” is common in Old French fabliaux in the discussion of sex.75 But this scene does not detract from its related central image across the page in the Annunciation scene; it may have entertained the young Jeanne, but it also reiterates what occurs at that moment, when Christ is incarnated in Mary’s womb. Similarly, the playful game of Froggy in the Middle mirrors the betrayal and mocking of Christ on the opposite page. We may interpret motifs that poke fun at Joseph’s foolishness or cuckoldry analogously, as a kind of playful adornment of and refocusing upon central tenets of the Christian faith. Joseph’s role as nutritor Domini in the Hamburg Petri-Altar’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt scene, Sheila Schwartz’s primary focus in her article on the altarpiece,[iii] is really not negated, or even reduced, by the saint’s portrayal on the same diagonal, performing the same action, teeth bared, as the ass in the lower left corner. Furthermore, the humorous reading does not preclude clerical laughter—play did not belong to the realm of the laity alone. 76

Humor for Laity and Clergy

Humorous depictions of a saint like Joseph reveal the problems of categorizing the “sober” clerical and “irreverent” popular consciousnesses as occupying separate realms in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. With an understanding of late medieval joke making, we are able to perceive humor in prayer books and churches not as solely subversive but rather “at once against the law and on the side of the law,”77 according to Howard Bloch, who wrote on the genre of medieval fabliaux. The restorative nature of the joke, according to Mary Douglas, makes it “frivolous in that it produces no real alternative, only an exhilarating sense of freedom from form in general.”78 Laughter in the late Middle Ages could operate within the controlled and acceptable framework of society, creating freedom from fear and the other. This is made manifest particularly in the gargoyles of Gothic cathedrals, once “intended to turn away evil . . . [they] tend to become mere comic masks; by the fifteenth century the process is complete and, instead of threatening, they are intended to amuse.”79 René Girard writes about laughter and crying as closely related, in that both respond on some level to a loss of control.80 For carnival revelers, for example, all hierarchy and social control are suspended through celebration. The loss of social order and control, writes David Smith, is at once socially recuperative because it “evokes a special kind of sociable laughter, one that at its best frees us from the norms, fears and constraints that ordinarily rule our lives, but to the extent that it entails reversal, it’s also deep laughter, in that it means defeating some of our deepest fears.”81

Humor on the theme of the “world upside down” flourished within the aristocratic court centers of the High Middle Ages, perhaps arising from the desire or need for social order, an affirmation of cultural values in the face of chaos. As Keith Moxey and Michael Camille theorize, satire of traditional sex roles, chivalric attitudes, or the clergy could occur only in circumstances in which the status quo was not actually questioned.82 In the iconographic inversions of the marginalia, we see a loss of social order occur in the form of donkeys dressed like monks and knights fleeing snails (a clever play on words in Middle High German, in which schnell can translate to “fast” or “valiant”). While the world is turned upside down for the reader and laughter is elicited, the chaos is simultaneously contained, in a kind of inoculation from fear, including that of actual societal upheaval, as Jonathan Alexander suggests occurs with peasant imagery.83 In a way, therefore, apotropaism could be at work.

Satirizing Saint Joseph’s old age, marriage arrangement, and lack of enlightenment to the point of highlighting his cuckoldry, impotence, and foolishness did not, it seems, undermine the saint’s veneration because the very qualities in question were biblically necessary in order to ensure Mary’s purity. The aforementioned scholarship on the cradle plays reveals that laughter at the doddering saint bound not only the holy figures and subsidiary characters in the rocking of the child but also joined the saint to his audience by creating a pathway of relation. As a model of parenthood and piety, Joseph’s humorous imperfections created an avenue of empathic identification and self-affirmation, and were thus integral to—in fact, inextricable from—the saint’s elevation and veneration as a cult figure.84 The status quo, therefore, was in no way questioned or undermined by such characterizations. Like the knights fleeing snails of medieval marginalia, motifs that poke and prod at the chivalric conventions that the reader herself would have upheld, Joseph’s inversion is contained within the safe realm of his own religiosity. Laughing at Saint Joseph could become the equivalent of reinstating his important theological role—laughter could be a form of veneration in itself.85

No matter what the source, humor and play were central components of religious and civic life in the late Middle Ages.86As scholars like Aron Gurevich and Camille have rightly demonstrated, no strict separation between the Church and the social dynamics of popular culture actually existed.87 In fact, reversal and transgression appear to have permeated the festal behavior and humor of both clerical and lay higher and lower orders. Similarly, the idea that secular jokes and satirical prints, paintings, and tales would infuse religious imagery, even occupying the center of a sacred scene and underscoring its theological symbolism, should not be surprising within this context.

The most bawdy, raucous behavior during religious festivals like carnival and kermis were likely considered, even by clerical and civic authorities, to serve an important overall function. The humor of the “world upside down” engaged the clergy in the inversions of carnival festivity, as well as in smaller inversions like that of the Boy Bishop of Constance, the original setting for the Schwäbische Weihnachtsspiel of ca. 1400, one of the surviving cradle plays. The play incorporates a choirboy from the cathedral school who had been selected to be the schuler bischoff. Equipped with cope and crosier, he temporarily reigned supreme over the ludic cradle play’s performance several times a day and during the festivity of the Twelve Days of Christmas. The Feast of Fools, a festival typically celebrated on Innocents’ Day or on the Feast of the Circumcision, typifies an instance in which the clergy themselves sanctioned societal inversion, when the lower ranks of clergy were allowed to run wild. Despite many accounts of clerical participation in such celebrations, the festum stultorum, festum fatuorum, and asinaria festa were suppressed by the Church hierarchy as early as 1207, the year that Pope Innocent III condemned deacons who wore masks or participated in other revelries.88 This does not mean at all that clerical participation ceased to exist. The problem particularly incensed Jean Gerson, writing on March 12, 1445, as chancellor of the University of Paris:

Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the Hours of the Office. They dance in the choir dressed as women, panders or minstrels. They sing wanton songs. They eat black puddings at the altar while the celebrant is saying mass. They play dice there. They cense with stinking smoke from the soles of old shoes. They run and leap through the church, without a blush at their own shame. Finally they drive about the town and its theatres in shabby traps and carts; and arouse the laughter of their fellows and bystanders in infamous performances with indecent gestures and verses scurrilous and unchaste.89

Even the most bawdy forms of humor were readily employed by the educated and wealthy citizens of late medieval and Renaissance Europe, who participated as writers, performers, and audience members of rhetorical competitions like the Brabantine Landjuweel. The facetiae of such competitions were filled with familiar erotic puns like the sexual entreatment of male market-goers to unbutton their purses.90 In his study of the social significance of Shrovetide and carnival, which Sebastian Franck described as those “three mad days”91 immediately before Lent, and their associated hilarities for the late medieval German city, Eckehard Simon employs accounts written by town authorities who tried to keep the revelry in bounds, as well as those of chroniclers, playwrights, and satirists. Such town-wide celebrations began in the thirteenth century and continued to increase in “madness” until the Reformation, with town authorities intensively involved in promoting and sustaining them, insisting each year that the various guilds and performers participate, lest they be fined. The town government likewise financed the stage plays, dances, tournaments, and games, each a particular social expression of the city’s prosperity. Yet they also apparently could not control the widespread obscenities of revelers; the Nuremberg constabulary was ordered to prevent the public from employing “bawdy words and indecent gestures,”92 while many cities, including Nuremberg, insisted that only the upper classes could wear masks to conceal their identity.93

Sebastian Franck’s Weltbuch, published in 1534 and based on the humanist Johannes Boemus’s De omnium gentium ritibus (ca. 1520), which describes carnival behavior at Mainz, reveals the centrality of the bawdy and erotic in carnival’s ritual games and practices. Franck attests that people frequently “ran through the streets naked, completely bare, without any shame.”94 Revelers were also wont to carry around a likeness of their genitalia, while in 1492 in Nördlingen, Hanns Geyr of Kemnaten and Michel Geissler of Augsburg costumed themselves, one cross-dressing as a woman, and proceeded through the city streets performing “unchaste acts in front of the people.”95 Outside of carnival, this was considered a very severe offense. In 1348, the Nuremberg council exiled Ulrich the purse maker for five years for exposing his “tool” (geschirr) to some ladies.96 Apparently just as common were the practices of cross-dressing, dressing as old people, or wearing clothes backwards or upside-down. An ordinance of the Goslar council in 1450 insisted that “no man is to dance in a woman’s dress and no woman in a man’s outfit.”97 In 1482, the Franciscans of Ulm apparently also ran about the streets in womens’ clothing during Shrovetide. Like exposing oneself in public, cross-dressing was considered a severe infraction outside of carnival, particularly for women.98

Throughout all of these activities and rituals, and their underlying strand of social inversion, obscene behavior—in various forms, including lewd gestures and gluttonous eating and drinking—was at the forefront of Shrovetide. But despite the Bakhtinian desire to link carnival revelry to the lay folk alone, exclusive of the town and ecclesiastical authorities, church and council played an integral role, reminding the guilds each year of their respective roles in the upcoming carnival days, thus supporting a not-so-separate framework for societal inversion and release.99 Religious plays, inclusive of lewd behavior, occupied central stage, while these and other performances conveyed relevant political and moral messages to their audience.100 Lübeck’s wealthy merchant class occupied the center of carnival dancing in the streets, their abundance attesting to the city’s past and future prosperity. Hilarious, obscene, and bawdy behavior during carnival was thus part of the city’s continuous religious and civic functioning and prosperity and intertwined rich and poor, sacred and profane.101 The liberation, parody, and social inversion of religious rituals and festivals could have an inoculating rather than infectious effect on society and the city, in that through the containment of transgressive actions or reversals, the city’s institutions could be strengthened.102 In such practices, a kind of immunity was granted to those doing the reversal, such as friars dressing as women and wealthy burghers playing peasants; in other words, their performance, although it transgressed social norms, did not provoke punishment or censure while it was contained within an already allocated space or time.103 The creation by a society of set spaces and times for societal inversion to take place seemingly occurs because the result of such temporary disorder is innocuous or apotropaic. It is believed to drive away dangerous disorder.

The iconographic trends in private devotional and public images of Saint Joseph cannot be explained only by recourse to the functional roles of humor. The development and popularity of religious images had much to do with the nature of late medieval religious practices. Even the most public form of religious image, the altarpiece, was typically commissioned by a member of the laity and decorated with particular attention to the layperson’s salvation and devotional concerns, despite the piece’s liturgical function as a prop for the celebration of the Eucharist. Thus, even the more secularized, comical iconography relevant to Joseph would not be out of place on an altarpiece, whether in a parish church or cathedral. But this fact is not even necessarily relevant to the explanation of the presence of humor on a functionally religious altarpiece. Once we accept that humor and play were in fact central to late medieval religious life for both laity and clergy, and that jokes both obvious and subtle are present in a large number of religious depictions of Saint Joseph, we can begin to see that play and humor are present in all kinds of religious commissions. What we formerly might have considered an artist’s weakness—for example, a rather diminutive dragon of unconvincing ferocity held prostrate by the foot of a Saint Michael—becomes instead a comical display of the artist’s wit in reducing a fearsome demon to an accessory.

Humor and satire are also present on altarpieces that were painted by members of the clergy, revealing that such forms of play cannot be explained away by citing the concerns of the laity—and certainly cannot be understood as a form of education alone. The high altarpiece of the Franciscan Göttingen Barfüsserkirche, which now resides in the Niedersächsiches Landesmuseum, Hannover, was probably painted by one of the brothers in 1424, and commissioned by a family with close ties to the order. Miniaturized scenes of a hunting group and a pilgrim playing the bagpipe satirize the human weakness present in the central religious imagery, while tiny dogs cavort throughout the panels, and a ridiculously small midwife cooks porridge beneath a vision of Christ that conforms to the papal-endorsed doctrine of the Nativity described by Saint Bridget of Sweden. Humor, play, and theology were in no way irreconcilable for this artist.

Multivalence in the Mérode Altarpiece

The Mérode Altarpiece (fig. 23), a work that exemplifies early modern lay devotion to Saint Joseph and to the Holy Family, may also reconcile play and theology. The mousetraps, one on the table and one on the windowsill, as we learn from Meyer Schapiro, have been invested with the Augustinian metaphorical meaning as being snares for the devil. The inclusion of Joseph, therefore, serves to highlight his marriage to Mary as a trick to fool the devil, masking the divinity of Christ’s birth.104 Yet the most common analogies with respect to mousetraps, drilling, holes, prominent (or noticeably small) tools, and the coupling of old men with young women had much to do with the humorous sexual themes of French fabliaux (Schapiro himself points out the multiplicity of mouse/vagina/Satan metaphors). When considering this intimate depiction of the Holy Family, and the Virgin as the Madonna of Humility,105 it is not so difficult to imagine that Campin’s mousetrap could have been intended as a kind of linguistic deflection made visual, or that Joseph’s drilling carried undertones of a witty pun on the “carpentry” of sex, and that the Ingelbrechts might have been able to find some humor in such imagery, in addition to theological symbolism. The aforementioned copy of Campin’s lost Life of Joseph (see fig. 15) itself hints at the potential for wittiness on the part of the artist, at the very least. Whether such wit is intentional or not, the drilling Joseph of the Mérode Altarpiece does mirror the risible Joseph of the Master of the Legend of Saint Barbara’s Adoration of the Magi (see fig. 7), in which a mousetrap is also present (and in which the donkey apes the saint’s pose).

In the Mérode Altarpiece specifically, the trapping of the elusive mouse is exactly what is missing in Joseph’s panel, while the central panel depicts the most important consummation of father (God) and mother (Mary) in Christian history.106 This potentially playful reference to the cuckoldry of Saint Joseph is perhaps a witty reiteration of Christian doctrine, suggesting that early modern humor, when present, did not detract from religious significance. But this witty play does not emerge without context or precedent; the marginalia of Jean Pucelle’s Annunciation miniature in the Book of Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux (see fig. 22) similarly play on the sexual undercurrent of Mary’s impregnation. An iconographic reading that acknowledges humor and play in the presence of the mousetrap, similarly, does not negate the arguments of Meyer Schapiro, Charles Minnott, and Cynthia Hahn107 but rather reinforces them, for the mousetrap could have functioned as a kind of multivalent image, harboring both theological and humorous implications.

As a prominent figure and responsible caretaker/laborer in the Mérode Altarpiece, Joseph does indeed perfect the marriage model of the Holy Family, as Hahn writes. But Joseph himself was also understood to be imperfect, as reflected in the Bible, plays, legends, hymns, and art, which tell of his old age, cuckoldry, drinking, and bumbling as he attempted to care for the Son of God despite his incomplete enlightenment. When we consider Joseph’s cult within the context of the lesser laity and clergy, we are able to move beyond the all-too-common assumption that in art and in literature, Joseph was portrayed in either one of two roles that are “mutually exclusive. . . . In some Gothic representations he was depicted as an old, tired buffoon, a butt of jokes. Alternatively, he was conceived of as the hard-working foster-father of Christ, the worthy companion and helpmate to Mary, and the strong, capable head of his household.”108 When we look to evidence beyond the theological writings of such giants as Jean Gerson, Pierre d’Ailly, Bernard of Clairvaux, Ambrose, and Augustine, we begin to see that these roles in late medieval representations often did not contrast, nor was there a clear-cut break in the early fifteenth century towards more sober representations of Joseph because of the saint’s ecclesiastical champions. Joseph’s dually comical and virtuous nature did not exist in separate, distinct manifestations but rather cohered in single artworks,109 suggesting that the saint’s importance for medieval and early modern peoples can be reconstructed from more than theological discourse alone. Jean Gerson’s insistence that Joseph was a strong, handsome man of about thirty-six when he married Mary clearly fell flat in the eyes of many artists, and his arguments were relatively contemporary. If humor appealed to the Duke of Burgundy in his personal tabernacle, where a barefoot Saint Joseph is depicted knitting his stockings together,110 or in the retable he commissioned for his oratory chapel, in which Joseph is overshadowed by ass’s ears, it may have infused the Ingelbrechts’ commission approximately twenty years later.

Late medieval and Renaissance images of Joseph reveal an important point to us: rather than focusing exclusively upon theological symbolism, the religious experience of images could also privilege humor as a central, reinforcing component of sanctity, and not for the laity alone. This is proven by humor’s presence not only in manuscripts and private devotional panels and polyptychs but also in works used for liturgical practices, including large-scale altarpieces; it seems that humor was not necessarily more common in works used for private devotion. Like the marginalia of medieval manuscripts, humor and irony could amplify theological symbolism in Renaissance art. Humor’s relevance to Joseph’s veneration may have functioned much like illusionism, in serving to familiarize the saint to the viewer and devotee desiring to experience the divine in human terms, providing a kind of tangible, affective pathway. But it also served many other functions, social and rhetorical, that merit further exploration.111 Visual jokes about Joseph’s cuckoldry and bumbling introduced socially binding mirth for those doing the laughing. But more importantly, rather than detracting from the saint’s veneration, they might be understood as vehicles for highlighting his most important virtues—his chastity, old age, and care for the Son of God despite his incomplete understanding of the situation—thus emphasizing the most important aspects of his sainthood that the viewer would have known to be truths. Laughter, in this sense, may be understood as a form of veneration itself, in that it reinforced the central tenets of the Christian faith with respect to Joseph’s role in the salvation of mankind.