A group of seventeenth-century Dutch portraits depict their subjects awkwardly hunched or bent over, many in the process of rising from a chair. These appear to contradict the upright posture and graceful movement promoted by early modern conduct books. They may be understood, however, in light of the pressures to more precisely measure time that were being promoted in commercial circles and the debates concerning the nature of time raging in academic ones. This article argues that instead of awkwardness or lack of social grace, seventeenth-century viewers must have experienced the momentary quality of these portraits as intensifying the presence of the portrayed and reducing the psychological barrier created by the painted portrait as a physical object.

In the fourth century Saint Augustine asked himself, “What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it to one who asks me, I know not.”1 My interest in time and Dutch portraiture originated in the observation that over the course of the seventeenth century, Dutch artists produced images that display an increased awareness of temporality. It is a commonplace of art historical formal and iconographic analysis that flower still life paintings open the century as relatively stiff bouquets of flowers in full blossom and close the same century as lush blooms, drooping petals, spent of their life, emphasizing the passage of time — underscored, in some works, by the addition of an open pocket watch. Around 1600 foodstuffs are arranged in orderly fashion across table tops, while after 1650 table cloths are wadded, lemons peeled, and beakers careen wildly or are thrown over entirely. Vessels in seascapes arrive on calm seas until the second half of the century, when wild storms threaten ships with whipped waves; hulls are occasionally split entirely into two. History paintings move from passively relating narrative to actively engaging a particular moment of contemplation or the horrifying moment of death, blood squirting before our eyes. While sixteenth-century group portraits present row upon row of heads and shoulders arranged like vegetables displayed at the local farmers’ market, a seventeenth-century innovation was the production of animated moment — such as Rembrandt’s depiction of Captain Frans Banning Cocq delivering marching orders to his men in the Nightwatch (fig. 5).

Nowhere is this increased sense of temporality more puzzling to me, however, than in a number of seventeenth-century Dutch portraits. How could seventeenth-century Dutch men, and a few women, commission from well-known artists, for substantial sums of money, portraits of themselves depicted in what appear to us to be comically awkward poses? Was the musician portrayed by Thomas de Keyser a hunchback, or just lurching about the room (fig. 1)?2 Why did the man painted by Rembrandt in 1633 want to be remembered for waving at the viewer while rising from his chair (fig. 2)?3 Did the preacher pictured by Bartholomeus van der Helst actually mean to be recorded as if he had just seen a ghost (fig. 3)?4 And did Jacob de Wit in Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp really want to be preserved — for all time — with his neck protruding from his collar in a pose that resembles nothing so much as a chicken about to pluck a kernel of corn from a feeding-trough (fig. 4)?5 These are only a sampling of similarly awkward poses created over the course of the century by artists including Werner van den Valckert, Nicolaes Eliasz Pickenoy, and Bartholomeus van der Helst for other sitters — or half-standers as they appear to be.

One element linking all of these paintings is that the figures are caught in a moment of time so short as to be almost instantaneous, an instant so brief that only in the twenty-first century do we have a suitable term for it: a nano-second. With this in mind, I here examine some of the varieties of time, both as idea and as experience, as embodied by a number of seventeenth-century Dutch portraits — some that are less familiar and a few widely known classics. While iconographic study of images unpacks the associations of objects, my interest here lies in the cultural associations of the visual representation of a theme: gesture, movement, and the temporality they imply.

When mentioned at all, awkward animation in group portraiture has largely been credited to the naturalism demanded of narrative. Noting the “outlandish figure . . . who is fiddling with his top boot” in Govert Flinck’s Civic Guardsmen of the Company of Captain Joan Huydecoper and Lieutenant Frans van Waveren (fig. 6), Riegl observed: “it seems to the modern way of thinking to be the product of poor taste. What on earth, one wonders, could the artist possibly have been thinking when, in the midst of the dignified, ‘official’ posturing of the three officers, he unabashedly inserted the figure of a man who apparently had nothing better to do than adjust his footwear? The answer is simply that he intended this very effect. . . . Flinck wanted the painting to be seen clearly as a genre scene, whose ordinary subject matter would be comfortably familiar to any viewer’s subjective experience.”11 Similarly, early descriptions of Rembrandt’s Sampling Officials of the Drapers’ Guild explained the bent-over pose of Volkert Jansz, caught mid-air as he rises from his chair, as responding to an interruption from the room (fig. 7).12 Preparatory drawings and an X-ray reveal that Rembrandt originally portrayed this figure standing as the others sat, subsequently working out his precise location and half-standing pose.13 In his critique of this narrative explanation, Henri van de Waal argued that the pose was instead a clever solution to the formal problem of giving sufficient space and attention to each of the five men around the table. Finally, most commentators on portraits of single individuals depicted in motion echo Jakob Rosenberg’s praise of implied naturalism in the work of another artist: “Frans Hals’s success in overcoming the limitations set by portraiture and saving it from dull conventionalism, was largely due to . . . his amazing emphasis upon momentary expressions, causing his figures to palpitate with life and gaiety.”14

Academic concepts of time, pressures to measure increasingly smaller units of time, and the resulting subjective experience of time underwent radical transformation over the course of the seventeenth century. This paper suggests that some of the very novel and experimental qualities of these portraits provide a material and accessible visual counterpart to, and in some cases precedents for, pressures to more precisely measure time that were promoted in commercial circles and the debates concerning the nature of time raging in humanist and academic ones.

My discussion of these portraits is divided into three — albeit overlapping — kinds of representations of the body in time which, in turn, produce different temporal relationships between the viewer and the portrayed. These are: first, duration or what we may term God’s time — eternity or cosmological time. While eternity can be neither pictured nor fully experienced, it is an idea that can be represented through iconographic motifs, which, as we shall see, change over the course of the century. Second, sequential time, or what may be called the represented subject’s time. This is produced through apparent narratives created by dividing time into pieces and picturing a moment that implies segments of time: a “before,” a “present,” or an “after.” Third, arrested time, or what may be called the viewer’s time. This is an isolated segment of narrative time which, in its pictorial form, so vividly and self-consciously engages the viewer that she or he no longer can simply contemplate the subject but is compelled to psychologically interact with the subject in present time.

Duration: God’s Time

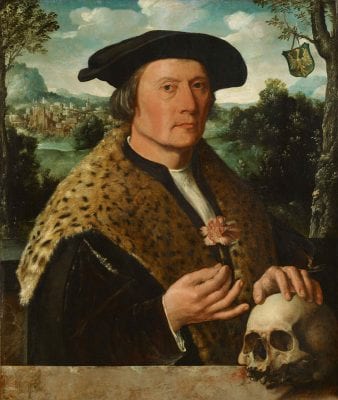

The Christian concept of eternal time is ultimately based upon a system articulated by Aristotle, who in the fourth book of his Physics explained the world of the senses as being linked to, and produced by, the motion of the celestial spheres.17 This was a timeless system, outside of, and extrinsic to, man’s limited sense experience. Christian eternity, implied by the world landscape viewed over Occo’s shoulders, existed before he was born and will continue after his death.

This reference to God’s eternal time, and the viewer’s steady participation in it, continued to figure in portraiture through the middle of the seventeenth century. Frans Hals employed it in his portrait of a sixty-year-old man holding a skull (fig. 9). While, to use Harry Berger’s term, this subject “poses” for us, his gesture asks the viewer to contemplate man’s life as but a small segment of the larger unbroken Aristotelian–Christian time of eternity.18 Life is linked to the cosmological order which can be contemplated in time but whose duration is not itself broken into discrete moments.

During the first half of the century, the mechanical pocket watch begins to accompany the skull as an iconographic reference to cosmic time, as in a still life by Pieter Claesz from 1630 (Mauritshuis, The Hague), where a winding-key is attached to the watch by a rich blue ribbon.19 Gerard and his sister Gesina Terborch centrally located a pocket watch on the table beside their brother Moses in their portrait of him painted shortly after his death in the Second English-Dutch war (fig. 10). The ubiquitous skull is almost hidden in the lower right. Here, too, I would argue we are intended to experience eternal or cosmic time: Moses is physically dead, yet stands before us as he was in life, as he remains in the memories of his beloved siblings, and as he exists resurrected in eternal life. As in all such portraits, the reference to eternity is iconographic, and the relation to the viewer one of duration, time stilled. As the viewer surveys the portrait she is offered the opportunity to contemplate Moses’s life on this earth as well as her own transience and promise of eternal life to come.

Time in the Seventeenth Century: Man’s Time

Until the middle of the seventeenth century, the measurement of time was notoriously inaccurate. Time was what we might call “soft.” The best that timepieces could manage was to keep approximate track of the hour, the unit by which time was measured. Clocks, such as those installed on the tower of the Zuiderkerk in Amsterdam, finished in 1614, or the new Amsterdam Town Hall, completed in 1655, originally bore only a single hand marking this hour, and this hour hand could gain or lose up to fifteen minutes a day.

The precise measurement of time, however, was rapidly becoming an important issue in commercial life. The clock held promise for increasing the accuracy of determining a ship’s location on a long voyage, essential for avoiding shipwreck, as well as for reducing the voyage time — and attendant costs — of merchant fleets. For several centuries, navigators had been able to ascertain a ship’s latitude — its position relative to the equator — by using a quadrant to take measurements based upon the horizon and the location of the sun or stars. However, establishing its longitude — the distance traveled around the earth — was more difficult and necessitated knowing the time of day with precision. While the creation of a water-resistant, suitably accurate timepiece had to wait for another one hundred years, merchant adventurers and the Dutch East and West India Companies, as well as governments, were all madly working on the task.20

Among the most creative minds to tackle the problem was Christiaan Huygens, the monumentally talented scientist who, among other things, discovered Titan, the first of Saturn’s moons, argued that light consists of waves, and played a central role in developing today’s calculus. Huygens revolutionized timekeeping by applying to the clockwork an observation about the regularity of a pendulum first made by Galileo.21 In 1656 Huygens commissioned clockmaker Salomon Coster to create a pendulum clock to his design, which made possible a radically more accurate timepiece. Coster’s first pendulum clock had a separate smaller dial with which to register the minute hand, boasting of its high degree of accuracy.

The tempo of public life became increasingly regular. In the realm of transportation, for example, trekvaarten, or horse-pulled barges, moved about the countryside on a regular schedule.22 From Amsterdam one could depart for Haarlem every hour, south to Gouda twice, and to Utrecht three, times per day, north to Hoorn twelve times daily, and east to Naarden or Weesp six times each day. Bells were rung to announce the departure time, and many barges were equipped with hourglasses. A skipper faced heavy fines for failure to keep to the timetable. Barges’ schedules became so reliable that by the third quarter of the century they were printed. Perhaps the most telling indication of their temporal reliability was the observation made at the turn of the nineteenth century by English visitor Benjamin Silliman, who wrote that “on account of the equal motion of the Schuits [canal barges], the Dutch reckon their distances in time.”23

The increasing temporality of external life played a role in the internalization of the day-to-day experience of time. Time began to be experienced in personal, subjective terms in and on the body; duration was moved from the abstract and mathematical realm of celestial bodies to the intrinsic movement of self and objects through the course of the day. The ability to measure time more precisely affected everything from professional and personal relationships — the convenience, for example, of being able to meet a friend or family member at a specific hour — to clocking the length of sermons.

This kind of attention to the passage of personal time began to be noted in personal life as well. On July 18, 1643, philosopher René Descartes sent his watch to his friend Gerard Brandt to have it fitted for a chain. On the outside of the letter Descartes supplemented the address with the location and time of posting: “In the 12th hour, on the Rokin, by the Beurs, at Amsterdam.”24 The personal diary kept by Constantijn Huygens of his trip to Venice in 1619 to 1620 records the time of events over the course of his day. On April 25, 1620, he recorded: “Around the second hour in the afternoon, we rode out of the Hague in six carriages. In the evening toward the seventh hour we came to Bodegrave, where we spent the night.” The following day he wrote “The 26th, Sunday, . . . around the ninth hour we were finished with breakfast, and around hour ten we left where, after almost three hours, we arrived in Utrecht.”25 The Hague schoolmaster and poet David Beck similarly noted the hour and duration of his activities, along with the weather, in the diary he kept for the year 1624. On May 17, for example, he wrote: “Glorious weather, neither too warm nor too cold, with a cheering rain in the evening around hour 8, lasting but one-half an hour. . . . In the evening around hour 8 I paid a visit with grandmother to Roeltin, ate an apple omelet [Appelstruyf] with sweet cream, talking together over a thousand little things, came home at last around 11 and one half hour, and then went directly to sleep.”26 As contemporary historian of time Stewart Sherman has noted, recording time in a private diary is a way of owning it.27 Time was becoming privatized, appropriated for personal experience.

While pocket watches became ever more available, their inaccuracy was a constant frustration with which individuals struggled. The account book of the Utrecht patrician Carel Martens, for example, included a line on May 21, 1642, for the annual fee of 3 guilders, 3 pennings, that he paid to his watchmaker to keep his pocket watch running on time.28 Only three decades later Christiaan Huygens again transformed time with the balance-spring clock, which permitted the miniaturization of the minute movement for pocket watches.

Accompanying the increasing importance of time in commercial life, and the awareness of time in the private sphere, was the debate among academics about the impact of Copernicus’s heliocentric universe upon Aristotle’s conception of time as the indivisible and eternal product of the movement of the heavens around the earth. In his Institutionum Metaphysicarum written in 1623, University of Leiden professor Franco Petri Burgersdijk wrestled with Aristotle’s concept of time, distinguishing tempus realie (real time), or the continuity of existence that exists outside of the mind, from tempus imaginarium (imaginary time), or time as measured by the mind’s comparing different instances of motion.29 These two understandings of time may be described by what I have termed God’s time and man’s time. I would now like to turn to two forms of the latter in imagery that we might distinguish as the portrayed subject’s time and the viewer’s time.

Narratives of Action: The Portrayed Subject’s Time

Individuals had thus begun experiencing and recording time in discrete units that had their origin in the personal perception of changes in the material world. This internalization and privatization of time had important consequences for a new understanding of temporality. Time was no longer only an eternal continuum but was now understood as being created by the moments into which it could be broken in man’s mind. It is thus not surprising that artists began to experiment with new forms of temporal expression. I would like to suggest that the interest in “liveliness” evidenced by seventeenth-century Dutch portraitists was grounded in, perhaps even generated by, a new awareness of temporality.30

Earlier group portraits, such as Dirck Jacobsz’s Men of the Harquebusier Militia of 1529, depict their subjects in a variety of poses and gestures but, as Alois Riegl discerned, each is affectively unrelated to those of the other figures (fig. 11).31 Articulating this in terms of temporality, we observe that within the confines of a single frame the pose of each figure is a discrete event of unspecified duration; temporally it may be said to be linked to the external and universal time of the cosmos. The Nightwatch (see fig. 5) also pictures men in various poses. Indeed, it even includes what has been described as a narrative in the sequence of figures loading a musket, firing a musket, and blowing off the pan, a sequence which, as Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann has elaborated, brings to mind the images in the instructional handbook Jacques de Gheyn designed for the army of the Prince of Orange.32 But in contrast to earlier group portraits, these movements are pictured as occurring simultaneously and, as Riegl noted, all are subordinated to the central action: Captain Banning Cocq giving the order to march out. His gesture divides time into the discrete moments of a narrative that includes a “before,” a “present,” and an “after” — moments that the viewer’s mind must stitch together. Here time may be said to refer to the time of the figures portrayed, or the subject’s time.

Arrested Time: The Viewer’s Time

I now wish to return to those individual portraits whose apparently awkward poses have so puzzled me. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, I have always wondered whether Thomas de Keyser’s portrait of a musician and his daughter of 1629 described a physical deformity (see fig. 1). While such unstably posed figures are more readily absorbed into the imagined temporal narratives that inform group portraits, when employed for a single figure these poses are similarly arresting. Recent discussions of the impact of figural stances in history painting may be productive for our thinking about these portraits. With reference to seventeenth-century texts on art, Eric Jan Sluijter and Thijs Weststein have argued that animation was understood to bring historical figures, and the narrative, into the present affective life of the viewer.33 Instead of awkwardness or lack of social grace, seventeenth-century viewers must have experienced the momentary poses of these portraits — particularly those that were most unstable — as intensifying the presence of the portrayed and reducing the psychological barrier created by the portrait as a physical object. Thomas de Keyser’s musician may well have a spinal deformity; at the same time, the emphasis on his awkward splayed-knee stance and half-lifted lute thrusts him into our space and time for just an instant, producing a sense of embarrassment on his behalf that instills in us an awareness of viewing in our time.

Conclusion

While along with Saint Augustine, we may find it difficult to explain time in words, images have the ability to palpably invoke the experience of time. Just as Christiaan Huygens was working on his pendulum clock, Christiaan’s father Constantijn mused about the relationship of portrait painting and time:

God’s handiwork, which I can visit, own and see

I need no copy of it from human hand.

However, there’s one part of painter’s art can please me:

That piece which lays its hand to slow the wheel of time,

And places the grandfather of my father’s sire

Now in my sight, as if he lived today or yesterday

And allows the children of my children to inherit

The countenance that goes with me to death and to decay.

Is painter’s skill not more the master than is time?

Yes, it preserves in oil these perishable things.34

While nearly a century later Gotthold Lessing was to write, “bodies . . . are the peculiar objects of painting” and “actions . . . the peculiar subjects of poetry,”35 Dutch seventeenth-century portrait painters took time implied by movement as their subject, with moving and memorable result.