Jerónimo Nadal’s meditative treatise Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia of 1595 is a foundational Jesuit propaedeutic, for it taught the order’s scholastics how to convert the Gospels into exegetical images, which could then be utilized for prayer, preaching, and evangelization. Nadal invokes the term sublimis sparingly yet powerfully at five points in his treatise. My paper examines what it is about Christ that Nadal considered sublime, and how his understanding of the sublime as a rhetorical category is bound up with the Jesuit project of visualizing the verba Christi (words of Christ) and Christ as Verbum Dei (Word of God).

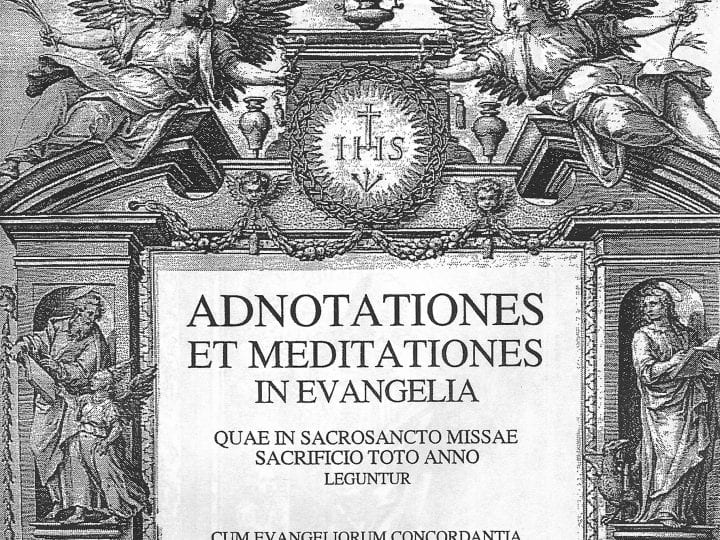

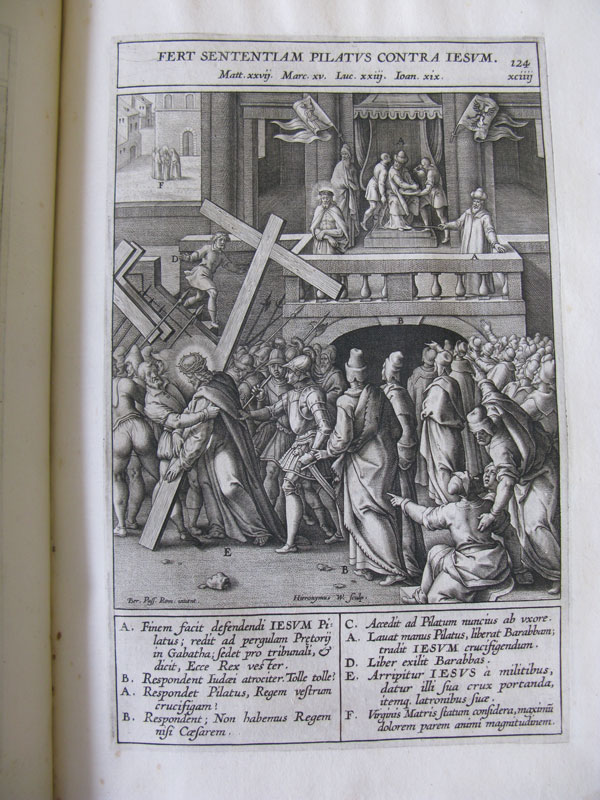

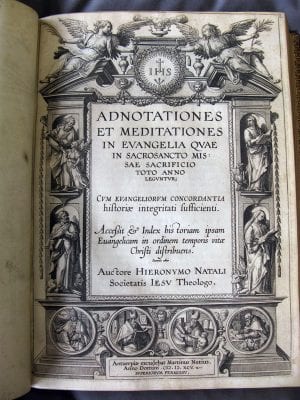

Composed by the Jesuit Jerónimo Nadal, S.J., at the behest of the order’s founder Ignatius of Loyola, the Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia (Antwerp: Martinus Nutius, 1594/95, editio princeps; Antwerp: Joannes Moretus, 1607, editio ultima), consists of 153 folio-size images, mainly engraved by the Wierix brothers of Antwerp, each of which is keyed to four species of complementary text: captions (adnotatiuncula), pericopes (evangelium missae), annotations (adnotationes), and meditations (meditationes) describe and interpret events from the life and ministry of Christ, as codified in the liturgical Gospels (fig. 1).1 The 153 chapters are generally made up of an image and these four species of text. Letters attach constituent scenes within the image to equivalently lettered textual passages within the corresponding chapter. If, say, the image is subdivided into scenes A to H, this same set of letters will be found embedded in the captions, then again in the pericopes, and yet again in the annotations. The sequence of topics thus established determines the topical order of the meditations that follow (figs. 2–5, 6–9). Whereas this device clearly derives from the tabular lettering of maps and atlases, Nadal’s jointly verbal and visual apparatus, comprising titular headings, pictorial images, and textual commentaries, springs from the tripartite arrangement of the emblematic motto, picture, and epigram. The Adnotationes et meditationes fulfilled multiple functions: it supplied Jesuit scholastics with exegetical spiritual exercises coordinated with the celebration of Mass from Advent through Easter; it provided the order’s schools, colleges, and worldwide missions with a potent machina (pedagogical apparatus) whereby the doctrinal truths encoded in the Gospels could be made discernible through a process of interpretative visualization; and, perhaps most importantly, it facilitated the production of scriptural imagines Christi that might serve as guides for the imitation of Christ in thought, word, and deed.

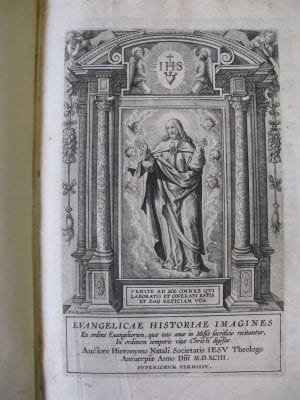

The Jesuits initially retained control of the 153 plates, having published the images alone in 1593 (Evangelicae historiae imagines) (fig. 10).2 Joannes Moretus, successor of Christophe Plantin at the Officina Plantiniana, acquired the plates in 1605 and published a second edition of the Adnotationes et meditationes in 1607, distributing the book through his extensive commercial networks. It qualifies as one of the most lavishly produced and beautiful books issued in Antwerp at the turn of the century and must surely have also circulated in the Republic, as Els Stronks has recently argued with reference to Willem Teellinck’s Ecce Homo, ofte ooghen-salve of 1622:

As shown in the case of Teellinck, the Republic’s culture should not be viewed from a national perspective and in isolation. The images of the crucified Christ that Teellinck opposed were seldom produced in the Republic at this time, but they had been especially popular in the Southern Netherlands ever since Antwerp was captured by the Spanish in 1585. Teellinck’s readers had access to this imagery because inhabitants of the Republic could travel to the Southern Netherlands somewhat more freely during the Twelve Year’s Truce and because books and prints produced in the Southern Netherlands were most likely also available in the Republic. An important specimen of this production is Jerome Nadal’s Evangelicae historiae imagines, printed in Christophe Plantin’s workshop in 1593.3

The chief nodes for importation and distribution of the Adnotationes et meditationes would have been the extensive network of Jesuit stations that operated under the nominal jurisdiction of the Dutch Mission and its vicar-general. Equally significant were the four Jesuit colleges active in the Generality lands: Maastricht (1575–1773), ’s-Hertogenbosch (1609–29), Roermond (1611–1773), and Breda (1625–37). Finally, wealthy Catholic families in Amsterdam and elsewhere who sheltered Jesuit missionaries would have also been able to procure copies of the book.4

Nadal, who was the founder of several Jesuit colleges and composed the Adnotationes et meditationes for the order’s rhetorically trained scholastics, utilizes the term sublimis very sparingly: it appears twice in chapter 102, “On the Events that Took Place after the Erection of the Cross before [Jesus] Gave Up the Ghost” (imago 129), twice in chapter 116, “On the Same Day [Jesus] Appears to the Disciples, Thomas Alone Being Absent” (imago 142), and once in the chapter “The Same Things Said about the Church, Are Said about Mary,” which forms part of the book’s long appendix, “On the Praises of the Virgin Mother of God” (fig. 2, fig. 6, 11–14).5 In all five places, sublimis is used to designate a characteristic peculiar to scripture and to Christ, the fulfillment of scripture, who brings both covenants to completion. We might put this as follows: Christus rhetor, when he wishes to signify the great mysteries of faith, speaks instructively in the simple style (genus subtile) and yet produces an effect so powerful that he seems also to speak movingly in the grand style (genus vehemens). This paradox proves even richer, for his diction, even when it appears most austere, is in fact replete with figures of thought and speech more typical of the grand and temperate styles (genera grandia et temperata), the most richly ornamented of the genera dicendi.

Nadal’s understanding of the term sublimis originated from his familiarity with Book 4 of Augustine’s De doctrina christiana, Longinus’s Peri hypsous (On the Sublime), and Hermogenes’s Peri ideon (On Types of Styles) and correlates to the doctrine of the three genera dicendi distilled in such handbooks as Cyprien Soarez’s De arte rhetorica libri tres, ex Aristotele, Cicerone, et Quinctiliano deprompti praecipue deprompti,first published in 1568. It is first of all important to note, as Dietmar Till has lately pointed out, that prior to the publication in 1674 of Nicolas Boileau’s Art poétique and translation of Peri hypsous (Traité du sublime), the term sublimis, as a stylistic category, was usually subsumed into the terms grandis, gravis, magnis, or vehemens.6 It was seen, in other words, as compatible, if not identical, with the doctrine of the tres canones and, specifically, with the third and most elevated of these canons. Soarez summarizes the form and function of the stylus gravis as follows:

It is clear that one genre of speech is desirable for small matters, another for middling, and yet another for weighty. . . . Since then the orator’s offices should be three—to teach, to move, and to please: let the simple be used in proving [subtile in probando], the moderate in delighting [modicum in delectando], the vehement in disposing [vehemens in flectendo]. . . . In this genre [viz., gravis] stylistic vigor has either a maximum or minimum of sweetness. Ample, grave, copious, and ornate, this style truly exercises the greatest power, for it either forces itself or steals into the senses, implants new opinions, uproots old ones. Herewith will the orator [viz., Cicero] raise the dead, as in the case of Appius Caecus [through whom Cicero speaks in Pro Caelio]. In this style will the fatherland call upon someone, addressing him (as did Cicero in his senatorial speech against Catilina). This style exalts a speech through amplification and further elevates it by virtue of hyperbolae. As, for example: “What Charybdis so voracious?” [Philippic II.27] Or: “The ocean itself, by heavens!” [Philippic II.27] This style will inspire anger, compassion; it shall say: “I saw you and wept, and implored.” [Institutio oratoria XII.10] And it engages all the passions. . . . For it is proper that an eloquent orator speak about small things simply, middling things temperately, and great things gravely.”7

Longinus’s conception of the sublime style and its sources complicated this paradigm of the stylus gravis. The equation between genus sublime and optimus stylus (viz., gravis) appears explicitly, as Marc Fumaroli has shown, in Marc Antoine Muret’s Roman oration, De via et ratione ad eloquentiae laudem pervendiendi, delivered in 1572; his protegé Francesco Benci, S.J., then assimilated Muret’s Longinian variant of Ciceronianism into the rhetorical program and usage of the Collegium Romanum.8 Longinus, as is well known, enumerates five sources of sublimity in literature, two of them natural (viz., bestowed more by nature than by art), three technical (viz., artificially constructed): first, the tendency to think grand and noble thoughts; second, the influence of strong emotion; third, the use of figures and tropes, especially phantasiai (visualizations); fourth, the choice of lofty language rich in metaphor and ornate in diction; and fifth, the dignified and rhythmic arrangement of words.9 Whereas sources three to five are easily construed as stylistic in Soarez’s sense of the term, sources one and two make style a function of criteria that transcend the canonical categories of subtile, temperatum, and vehemens. As Longinus puts it; “I would confidently lay it down that nothing makes so much for grandeur as genuine emotion in the right place. It inspires the words as it were with a fine frenzy and fills them with divine spirit. . . . No, a grand style is the natural product of those whose ideas are weighty.”10 For an example, he paraphrases Genesis1:3 and 1:10: “so, too, the lawgiver of the Jews, no ordinary man, having formed a worthy conception of divine power and given expression to it, writes at the very beginning of his Laws: ‘God said’—what? ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light, ‘Let there be earth,’ and there was earth.”11 These simply formed lines nonetheless become epitomes of the grand style because they issue from the grandeur of Moses’s thoughts about God and are informed by his awe and admiration at the power of the Lord. The notion sublimis, thus applied, in allowing one canon (subtilis) to be construed as another (vehemens), provided the warrant for Nadal’s use of the term to describe the potent effect of the profoundly simple yet densely wrought words voiced by Christ from the cross and later, after the Resurrection, spoken to the disciples assembled behind closed doors in Jerusalem.

The interstylistic dynamics set forth by Longinus found additional support in Hermogenes’s Peri ideon, a text widely disseminated within advanced rhetorical circles, as Till has demonstrated.12 Among the seven basic “types” or “ideal forms” of style, Purity (Katharotēs, one of the subtypes of Clarity, Saphēneia), the narration of simple facts in a clear and familiar manner, is presented as indivisible from Dignity (Axiōma) and Grandeur (Megethos), the majestic and dignified portrayal of divine beings and things, as well as of human affairs having to do with divine matters (such as the immortality of the soul) or with heroic undertakings (such as the bridging of the Hellespont).13 Hermogenes, like Longinus, treats as axiomatic the identification of style with both language and thought; simple thoughts and simplicity of “approach” are seen as compatible with grand thoughts and grandeur of approach:

It is only natural to discuss Grandeur after the discussion of Clarity, for it is necessary to interject Grandeur and a certain amount of majesty and dignity into a clear passage. . . . The first order [of solemnity], as I have said, are those thoughts that discuss the gods as gods. The second order of solemn thoughts are those that discuss truly divine things. . . . The third order of thoughts that produce Solemnity are those dealing with matters that are by nature divine but are often seen in human affairs, such as the immortality of the soul or justice or moderation or other such concepts, or inquiries into life in general or what is law or what is nature or other such questions. . . . The fourth order of thoughts that produce Solemnity are those that deal with entirely human affairs, but those that are great and glorious.14

Moreover, implicit in the discussion of Clarity and Grandeur is the tacit acknowledgment that human and divine affairs may on occasion be comparable or analogous. This assumption would have made Hermogenes particularly attractive to Nadal, who implicitly utilizes the term sublimis to characterize the mystery of the Incarnation; because he was incarnate, argues Nadal, Christ could suffer in the flesh during the Passion, and, as a consequence, that same flesh could be glorified by the Resurrection.

Equally important to Nadal would have been chapters 18 through 26 in Book 4 of Augustine’s De doctrina christiana, in which he expounds the three styles: calm and subdued; graceful and temperate; exalted, majestic, and vehement. Augustine, perhaps responding to Longinus, argues that the “majestic style of speech,” unlike the temperate, which is always highly ornatus, can be simple in form, similar in this respect to the “calm and subdued” style, but differing from it in that majesty must perforce issue from passion of thought:

The majestic style of speech differs from the temperate style just spoken of, chiefly in that it is not so much decked out with verbal ornaments as exalted into vehemence by mental emotion. It may use, indeed, nearly all the ornaments that the other does; but if they do not happen to be at hand, it does not seek for them. For it is borne on by its own vehemence; and the force of the thought, not the desire for ornament, makes it seize upon any beauty of expression that comes in its way. It is enough for its object that warmth of feeling should suggest the fitting words; they need not be selected by careful elaboration of speech.15

He adduces the example of Galatians 4:10–20, altogether majestic though written in the austere style, almost without any ornamentation:

Again, in writing to the Galatians, although the whole epistle is written in the subdued style, except at the end, where it rises into a temperate eloquence, yet he interposes one passage of so much feeling that, notwithstanding the absence of any ornaments such as appear in the passages just quoted, it cannot be called anything but powerful: “Ye observe days, and months, and times, and years. I am afraid of you, lest I have bestowed upon you labour in vain. Brethren, I beseech you, be as I am; for I am as ye are: ye have not injured me at all. . . . My little children, of whom I travail in birth again until Christ be formed in you, I desire to be present with you now, and to change my voice; for I stand in doubt of you.” Is there anything here of contrasted words arranged antithetically, or of words rising gradually to a climax, or of sonorous clauses, and sections, and periods? Yet, notwithstanding, there is a glow of strong emotion that makes us feel the fervour of eloquence.16

The same holds true of the temperate style, as used by Cyprian to sing the praises of virginity in his famous encomium on this subject.17 Whereas in theory the simple style is used to teach, the temperate style to give praise or blame, and the majestic style to sway reluctant minds to do what is right, in practice the three styles interpenetrate.18 Sometimes, for instance, the same topic may be treated in all three ways in a single speech, “quietly when it is being taught, temperately when its importance is being urged, and powerfully when we are forcing a mind that is averse to the truth to turn and embrace it.”19 For Augustine, the three styles appear functionally to diverge more in degree than in kind: the quiet style, when it teaches people to accept as true something they had previously thought incredible, in fact facilitates a change of heart, even though, unlike the majestic style, it is not actually “mak[ing] them do what they knew they ought to do but were unwilling to do.”20 Furthermore, even the grandest, most awe-inspiring mysteries, such as the nature of the Trinity, when they are being taught, will be presented simply, clearly, and quietly. The student will surely be moved by the grandeur of this mystery, and, in a sense, he will also have been moved to do something—namely, to learn about the Trinity.21 The quiet style here differs in its effect from the majestic only to the extent that the student is receptive not resistant to his teacher. Augustine’s account of the three styles of sacred literature and oratory offered Nadal a flexible system that set off formal differences, even while allowing for significant elisions and overlaps of effect. The unifying purpose common to all three was, of course, the rhetorical effect of persuasion:

For as the function of all eloquence, whichever of these three forms it may assume, is to speak persuasively, and its object is to persuade, an eloquent man will speak persuasively, whatever style he may adopt; but unless he succeeds in persuading, his eloquence has not secured its object. Now in the subdued style, he persuades his hearers that what he says is true; in the majestic style, he persuades them to do what they are aware they ought to do, but do not; in the temperate style, he persuades them that his speech is elegant and ornate. . . . We, however, ought to make that [temperate] end subordinate to another, viz., the effecting by this style of eloquence what we aim at effecting when we use the majestic style. For we may by the use of this style persuade men to cultivate good habits and give up evil ones, if they are not so hardened as to need the vehement style; or if they have already begun a good course, we may induce them to pursue it more zealously, and to persevere in it with constancy.22

Nadal took this supple Augustinian doctrina rhetorica and attached it to the Longinian and Hermogenean category of the sublime, in order to demonstrate how the verba Christi become forceful conveyors of the mysteria fidei at the two key moments of salvation history, respectively commemorated on the first Sunday after Easter (chapter 116, imago 142, “On the Same Day [Jesus] Appears to the Disciples, Thomas Alone Being Absent”) and on Good Friday (chapter 102, imago 129, “On the Events that Took Place after the Erection of the Cross before [Jesus] Gave Up the Ghost”).23

The designers of imagines 129 and 142 made every effort to show Christ speaking; they thereby emphasized that his verbal ministry continued even during the Passion and after the Resurrection. The Roman draftsman Livio Agresti drew the first set of modelli in the early 1560s under the supervision of Nadal. He based his oblong drawings in pen and ink on the scripturally precise woodcut prints by Lieven de Witte featured in Willem van Branteghem’s gospel harmony, the Iesu Christi vita, iuxta quatuor Evangelistarum narrationes, artificio graphices perquam eleganter picta (Life of Jesus Christ, according to the four Evangelists, very elegantly portrayed through the art of drawing)(Antwerp: Mattheus Crom, 1537). De Witte often diverges from the pictorial tradition, instead preferring to cleave closely to the Gospel texts, and his meticulous attention to scripture was surely what attracted Nadal to these images. In fact, Nadal seems to have composed the Adnotationes et meditationes with De Witte’s images in view.24 After Agnesti’s death in 1580, the Jesuits, probably guided by his erstwhile amanuensis Jacobus Ximénez, attempted to bring his drawings into more precise alignment with Nadal’s manuscript. The Jesuit Giovanni Battista Fiammeri produced a series of red-chalk drawings between 1579 and the early 1580s, in a vertical book format, but these were deemed insufficiently detailed. In the mid-1580s, the master draftsman Bernardino Passeri, working after the drawings by Agresti and Passeri, completed the modelli ultimately utilized by the primary engravers, Jan, Hieronymus, and Antoon Werix.25

At every stage of this process, the imagines became more descriptive and in this sense evidentiary: the engraved settings, for example, are very detailed and correlate precisely to Nadal’s detailed accounts of the Holy Land; this is equally true of figural attitudes, gestures, and facial expressions, as also of the more ephemeral effects—time of day or night, atmospheric conditions, and kinds and degrees of illumination, both natural and divine—upon which Nadal occasionally dwells. The Adnotationes et meditationes possessed unimpeachable credentials: dedicated to Pope Clement VIII, approved by the imperial theological faculty at the University of Louvain, sanctioned by the Roman censor Franciscus Toledo, and protected by papal interdict against illicit vendition or reproduction, the book’s images, though novel in many respects, were considered orthodox and authoritative. They functioned as a virtual canon, launching new iconographies and establishing new pictorial traditions, as the proliferation of paintings and prints depicting the raising of the cross, all based on imago 128 (chapter 101), testifies.

Imagines 129 and 142 respectively focus on the words spoken by Christ from the cross and in the closed room in Jerusalem where he first reunites with the gathered disciples after the Resurrection. Engraved by Hieronymus Wierix after the drawing by Passeri, imago 129 forms part of a series of eight imagines in which Christ’s interaction with the Holy Cross is exhaustively described, starting with the laying of the cross upon his shoulder soon after Pilate casts sentence (imago 124, chapter 94) and ending with the Deposition (imago 132, chapter 105) (see figs. 15–16). Here the cross functions as the platform for Christ’s seven final verba (words, in the sense of short speeches), as the seven letters ranged along the cross-beam, each keyed to a verbum, indicate. That four cluster above the wound in his right hand, three above the left, implies that it is not merely Christ’s voice but also his very wounds that speak. The position of his head, inclined toward John, Mary, and the holy women, as well as the good thief, and indeed, toward all the representatives of earthbound humanity ranged in a circle around the cross, perfectly accommodates the tenor and tone of his final utterances. Engraved by Antoon Wierix after the drawing by Passeri, imago 142 portrays Christ twice: in the foreground he shows the disciples the wounds in his hands and feet, thus confirming that the man now speaking to them is Jesus himself, who died on the cross; in the background he stands farther from them to indicate that his speech is no longer conversational, but rather, formal, declamatory, and sacramental. He points toward the locked and bolted door to emphasize that in instituting the sacrament of Penance, he empowers or, better, obligates the disciples to go forth into the world and preach the gospel of the remission of sin. The gesture also serves to demonstrate that his words issue from a body different from the one they knew before: having been rarefied, it can now pass through solid matter without suffering any material impediment. Finally, his head is raised to signify that the words he enunciates constitute a breathing out of his spirit upon them: his speech blesses, enjoins, and establishes in equal measure.

It now remains to be seen how and why the words spoken by Christ in chapters 102 and 116 (imagines 129 and 142) were characterized by Nadal as sublimia. Let us begin with chapter 116, which posits a link between verba Christi and Verbum Dei that proves fundamental to Nadal’s usage of the term sublime. Imago 142 depicts the closed room in Jerusalem where the disciples, their faith bolstered by the eyewitness accounts of Peter and the women, await the appearance of the risen Christ (A) (see fig. 2). He materializes suddenly, greeting them with the words of reconciliation, “Peace be to you” (B). Startled they take him for a spirit (A bis), so he reassures them, showing various signs of his humanity, not least his wounded hands and feet; further to indicate that it is truly he, he asks to eat with them (B bis). Having been offered a piece of broiled fish and a honeycomb (C), he eats and then distributes the leftovers (B ter). Throughout all this, the doors remain firmly bolted to indicate that his body, now divinized and glorified, was subject to no material impediments (D). Finally, he again wishes them, “Peace,” confirms them in their mission to evangelize, expounds the scriptures, and, breathing upon them, institutes the sacrament of Penance (E). Positioned on an axis with the room’s closed doors, Christ’s attitudes and gestures are those of a teacher calmly discoursing: in B, B bis, and B ter he addresses the disciples and at the same time displays proofs that it is he, the risen Christ, who interacts with them. The pictorial emphasis on his dual action of speaking and showing serves as a platform for the annotations that parse his words, starting with the six, “Pax vobis. Ego sum. Nolite timere.” These words, counsels Nadal, must be heard as if voiced within the heart, where they have the power firmly to confer the peace of Christ (“Peace be to you”), sweetly to implant true knowledge of him (“It is I”), and strongly to dispel idle fears (“Fear not”), instilling timor Dei, salutary fear of the Lord, in their place.26

The three paired words, especially “Ego sum,” as Nadal avows in the adjoining meditatio, are sublimia dona (sublime gifts) that transmit an interior sense of the divine benefactions attendant upon the mystery of the Resurrection. They are sublime, first of all, in their profundity, for they penetrated the disciples interiorly and deeply, working in tandem with the bodily image of Christ revealed by his apparitio.27 In annotation B bis, Nadal had explained that this apparitio operated externally, in the manner of a bodily sensation: “Vision is wont to be construed as a kind of bodily sensation, judgment and certitude having been brought to bear.”28 This is why Christ, soon after his initial words, commanded the disciples both to see and to touch him, or, more precisely, as Nadal implies, subsumed the sensation of touch into that of sight: “‘See,’ he says, ‘my hands and feet, and know that I myself am here. Touch, and see, for a spirit hath neither flesh nor bone, as you see me to have.’”29 But conversely, he wished to touch them internally, to “throw open [their] hearts” to the “living and joyful presence of eternal salvation,” the workings of which are made manifest in his person (corda vestra . . . erat illa adaperturus . . . salus aeterna interius etiam, laeta & vivida praesentia & operatione).30 His opening words initiate this process of internalization which leads ultimately to the realization that Jesus, having risen, is now discernibly present as both God and man and, as such, embodies the promise of salvation and reconciles humanity and divinity, flesh and spirit: “It is yours, great Jesus, to stand with us, for you are God, infinitely steadfast and immutable: and yours it is to stand amongst us, for you are the mediator, both of God and of men [solus es Dei & hominum mediator]. Thus you stood in both ways, as God and as man, amidst the disciples, that is, amidst your Church.”31 The fuller meaning of such reconciliation is adduced by the blessing, “Peace be with you.” That these mere words also convey the blessing they enjoin speaks to their sublime efficacy as instruments of the Word, whence issues the promise of divine peace, as also the guarantee of its fulfillment: “And nor did you speak peace upon those disciples only, but also upon all generations who are or shall be of the Church: for your voice, your words, even though they were created things, yet belonged to the immensity of the Word and possessed divine power and the virtue of everlasting peace.”32

Sublimity inheres as well in the words, “It is I,” which Nadal interprets as the unfolding of the great mystery implicit in the name Jesus, “God is salvation”: “Nor did you say this alone, holy Jesus, but you added: ‘Ego sum.’ You revealed the power of your name, and what you had withheld from Abraham, and merely signified to Moses, you evinced to the Church, [showing her] the mystical sense of this immeasurable truth.”33 Sublime too are the words, “Fear not,” spoken not merely to instruct but rather to transform the disciples, whom fear, anxiety, and disquiet have rendered incapable of recognizing Christ, let alone of using his many spiritual gifts to spread the Gospel: “Attend, my disciples, I have stirred your hearts with joy, and have come to bestow my light and gifts: be assured, not timid, cast off the sorrows that have hindered you from doing your duty. . . . Christ added these things not only for the eternal instruction of the Church, but to amend the disciples who were using imperfectly the gifts they had received thus far: for they were troubled and fearful, and thoughts were arising in their hearts.”34 Nadal adds that the admonition, “Fear not,” like the blessing “Peace be with you” and the assertion “It is I,” was an external sign (externum signum) of his power to quiet storm-tossed spirits and to confirm in them a spiritual sense of his consolatory presence.35 When Christ then charges them to behold his hands and feet, he is exhorting the disciples to conjoin the sharpness of external vision and the internal acuity of spiritual vision, thereby enabling them to discern that as he died on the cross, so he now stands before them.36 His words—“Pax vobis. Ego sum. Nolite timere”—when seen in this light, bear witness to the Resurrection, giving access to a spiritual experience of this great mystery: “Whence the spiritual experience [spiritualis experientia] of my Resurrection will penetrate your hearts and abide in the Church and in all pious men.”37

In sum, Christ’s vox and dictio creata are sublime because they issue from and indexically signify his status as the Word, whence originated all creation. They are signa of the Godhead. The connection between verba and Verbum constitutes an implied allusion to the mystery of the Incarnation, as Nadal’s reading of “Pax vobis” indicates: the status of Christ as “solus Dei & hominum mediator” is tacitly analogized to his power of reconciling in himself the human faculty of speech and his singular identity as Verbum Dei. Similarly, Nadal’s reading of “Ego sum” discerns in this simple phrase the mystery of redemption latent in the salvific name of Jesus. And when “Nolite timere” is attached, the tripartite sentence can be understood to convey the promise of salvation guaranteed by the mystery of the Resurrection. These six words, then, are sublimely pregnant with divine meaning. Nadal adverts to Augustine when he states that Christ is both teaching and converting, in the sense of impelling, the fearful and hesitant disciples bravely to embrace their gospel mission.38 The implication is that the calm and subdued quality of his speech (a restraint evident from the way he is portrayed in imago 142) possesses an efficacy more typical of the majestic style.

The linkage between verba and Verbum, vox and mysteria, fulfills the first criterion of the sublime—namely, sublimity of thought having to do with God—adduced in both the Peri hypsous and Peri ideon as an essential source of sublime expression. Indeed, all three phrases—“Peace be with you. It is I. Fear not”—since they make allusion to salvation wrought by the divinity of Christ, precisely correlate to two laudatory passages in Longinus about sublime thoughts: his praise of Homer’s sublimely conceived verba which “represent the divine nature as truly uncontaminated, majestic, and pure” (Iliad 13.18–19, 27–29; 20.60);39 and praise of Moses for “having formed a worthy conception of divine power and given expression to it,” in a manner pithy but puissant (Genesis 1:3, 1:10).40 Christ’s first two phrases, in particular, designed as they are to elicit meditative “visualizations” of him—firstly, as a steadfast mediator who stood amidst the disciples and now stands firmly with the votary, secondly, as visibly bodying forth, then and now, the messianic promise implicit in his holy name—anchor Nadal’s usage of sublimis in the Longinian dictum that “weight, grandeur, and urgency in writing are very largely produced . . . by the use of phantasiai (image productions).”41 Longinus repeatedly celebrates the emotional power that imaginative pictures give to speech and writing, as in his paraphrase of Homer’s ekphrastic image of Hera’s celestial steeds: “so supreme is the grandeur of this, one might well say that if the horses of heaven take two consecutive strides there will then be no place found for them in the world. Marvellous too is the imaginative picture of his Battle of the Gods.”42 For Nadal, all verbal phantasiai are grounded in the pictorial image supplied by an engraved imago, which is then imaginatively amplified and animated by means of verbal figures that activate the faculty of spiritual vision. The imago Christi, revisualized in light of Nadal’s reading of “Pax vobis. Ego sum. Nolite timere,” gradually transforms into an enhanced phantasia of Christus redivivus, whose divine empowerment, made newly apparent by his apparitio, is the primary theme of chapter 116. Imago 142 is a kind of mise en abyme: the calm yet robust reaction of the disciples to the apparitio Christi (A), stands for and prompts the votary’s response to Nadal’s pictorial image of this apparition (see fig. 2). The image of Christ speaking becomes a template for our visualization of him as originary Verbum and source of the sublime verba addressed to us. Underlying this joint reliance upon pictorial imago and verbal phantasia is Longinus’s notion of the supreme power of visualization in oratory:

What then is the use of visualization in oratory? It may be said generally to introduce a great deal of excitement and emotion into one’s speeches, but when combined with factual arguments it not only convinces the audience, it positively masters them. . . . And then, to be sure, there is Hyperides on his trial, when he had moved the enfranchisement of the slaves after the Athenian reverse. “It was not the speaker that framed this measure, but the battle of Chaeronea.” There, besides developing his factual argument the orator has visualized the event and consequently his conception far exceeds the limits of mere persuasion. In all such cases the stronger element seems naturally to catch our ears, so that our attention is drawn from the reasoning to the enthralling effect of the imagination, and the reality is concealed in a halo of brilliance. And this effect on us is natural enough: set two forces side by side and the stronger always absorbs the virtues of the other.43

Nadal concludes with an extended speech in the voice of Christ that demonstrates how densely packed with sublime mysteries were his words confirming the apostolic vocation and conferring the sacrament of Penance (John 20:21–23). These mysteries signify the larger mystery—the Resurrection—that constitutes their true point of origin: “O sublime mysteries of divine effects! Accordingly, great Jesus, by many exceedingly great benefits you have made your Resurrection, adorned with the splendor of measureless glory, manifest to your Church.”44 These corollary mysteries not only represent this grander mystery; they are representative in another sense, for they propagate the mimetic logic of the imitatio Christi. When Jesus enjoins the disciples, “As my Father sent me, so I send you,” he licenses them to imitate his lifelong ministry and sanctions their efforts to mediate between him and the Christian faithful, as he mediated between God and men:

My mission to the world is now complete: through preaching the truth and confirming it by miracles, through my labors, Passion, and death, I conferred eternal salvation upon humankind; but in this selfsame mission I received the power of making you similar to myself, a power I now exercise by divine authority and virtue, as mediator between God and men. For through me God reconciled the world to himself; and through me he placed in you the word [of peace] and ministry of reconciliation. Behold you are my apostles, my legates to mortal men. Understand this truly: the nature of the mission given me by the Father must be imitated by you.45

Christ by his appearance to them, by his admonitory words, and by his election of an apostolic vicar (viz., Peter) makes discernible the mystery of their conversion into living likenesses of himself, united with him as he is with God, at one with his vicar as he is one with the Father (ut similitudinem meae & vestrae missionis agnoscatis).46 When he breathes upon them and grants the authority of absolving or retaining sins, he bestows their priestly function of imitating the Trinity, whose power of absolution and retention they merely instrumentalize: “and in your absolving the sins of men, our Trinity shall absolve; in your refusal to absolve, we shall likewise retain.”47 As these mysteries involve the imitation of divine prerogatives, so they represent the greater mystery upon which eternal salvation is premised and that thereby makes possible all these other benefactions.

On this account, the sublime effect of the mysteria results from a doubling of mimetic phantasiai: a sequence of words and conjoined actions allows us to visualize various analogies between God and men, Christ and his disciples, and these analogies, in parallel with the image of Christ’s visitation, enables us better to grasp the sublimity of the Resurrection. Since engagement with a pictorial imago initiates this process, it might be more accurate to say that the “image productions” are tripled not doubled. Nadal’s conception of the sublime here closely derives from Longinus, who insists that sublimity requires the poet (he is thinking of Sappho) densely to layer the ideas (viz., thoughts) he wishes to express and, more specifically (now thinking again of Homer), to make his text “dense with images drawn from real life.”48 Of course, like Longinus, Hermogenes, and Augustine, Nadal here operates under the assumption that divine mysteries, like God himself, are never fully comprehensible. What can be known is the spiritualis experientia of the sublime that evokes the nature of God, enabling appreciation of his otherwise fathomless mysteries.

If chapter 116 and imago 142 reveal how the sublimity of Christ’s words emanate from the mysteries they express, chapter 102, more fully than any other chapter, and imago 129 parse the form of these verba, showing how his final words from the cross exemplify three further criteria of the sublime advanced by Longinus: first, the “inspiration of vehement emotion”; second, “the construction of figures of thought and speech”; and third, the ennobling of language through the “use of metaphor and elaborated diction.” His words, in their capacity jointly to teach, to praise, and to move, are also shown inimitably to reconcile the simple, temperate, and majestic styles of Augustine. Imago 129 (see fig. 6), as the captions make clear, depicts the crucified Christ’s seven last words: he prays for his crucifiers (A); pardons the repentant thief (G); designates Mary John’s mother, and John her son (I); pronounces himself forsaken by God (K); states that he thirsts (L); declares that all has been fulfilled (N); and commends his spirit to God (O). Ranged across the transverse bar of the cross, these letters attach to Christ, the position of whose head, tilted to his right, indicates that he is speaking to Mary and John, as well as to the good thief. This speaking gesture is thus made to stand for the full spectrum of his utterances from the cross.

The annotations emphasize that Jesus spoke with great eloquence, his rhetorical gifts unabated. His every word was persuasive, not only to God but also to the people around him, even if circumstances might seem to suggest otherwise: “But why then were the Jews not instantly converted? First, because the effect of hearing a speech is not wont to show itself immediately, but rather, when divine providence so disposes. Shortly thereafter, many felt remorse, and they returned [to Jerusalem] striking their breasts. And that the majority of the Jews were [finally] swayed, we see in the Acts of the Apostles.”49 In spite of the devil’s wiles and the promptings of their rulers, the multitude remained attentive to the things Jesus did and said from the cross.50 Jesus, as Nadal points out, was speaking potently in a mixture of styles capable of seizing and sustaining attention. In asking God to forgive his tormentors, he spoke with great reverence and dignity (reverentia & dignitate).51 In declaring himself forsaken, he spoke with the utmost pathos, revealing how intensely, as a mortal man, he longed to be succored (hac voce expressit humanitatis commiserationem, & auxilij implorationem vehementissime).52 Commiseratio is that part of an oration intended most acutely to arouse compassion.53 Vehementissime betokens the wellspring of vehement emotion that impels his speech. As Nadal invites us to infer, Christ was conducting an internal dialogue with himself in two voices, the one vehemens, designed to move, the other subtilis, designed to explain (as Soarez might say); his moving outburst forthwith elicited a tempered response more explanatory than impassioned: “And yet Christ at once answers [himself]: These are the words of my afflictions, which I the gentle and most innocent lamb of God bear; for this cause do I suffer dreadfully—because monstrous and numberless are the sins of men which I absolve, on account of which I languish.”54 Even a single word, sitio (I thirst), connoting both physical thirst and a spiritual thirsting after human salvation, has the potential arrantly to transform the receptive auditor, as Nadal asseverates: “But herewith open your heart, letting that word, ‘sitio,’ penetrate your spirit; there let it spread mightily and presently gather strength. Great was Christ’s external craving for water, greater still his internal craving for our salvation!”55 As will be evident, the annotations utilize rhetorical terminology deriving from the sources we have been examining, all of which redound to the sublimity of the “septem verba dicta in cruce.” Jesus speaks nobly (dignitate), passionately (vehementissime), in a manner interiorly quiet yet exteriorly potent, his every word apt for piercing the heart and turning it spiritually. These are characteristics of the sublime style, as defined by Longinus and Hermogenes; the septem verba subsume elements from what Augustine called the subdued style and Soarez the simple, in a mixing of stylistic resources licensed by the Longinian notion that the sublime transcends the traditional genera dicendi, and by the Augustinian warrant given to elisions of form and function among the three styles.

The meditatio functions as a paraphrasis of Christ’s words, elaborating upon their nature and purpose, according to criteria borrowed from Longinus. The power of the septem verba issues from their singular identity among all the things he said during his life: this is because they are phantasiai of real things—not simply expressive of his suffering but coexistent with his wounds and torments. When Jesus speaks, it is these appalling vulnera that we envisage and see speaking to us. As Nadal puts it in his paraphrase of “Father, forgive them” set in the voice of Christ: “Look not upon their guilt, Father, which they fail to acknowledge, which I both acknowledge and feel, perceiving from my suffering and death how great is the offence of their sins; for my torments and death exhibit to me both the failure and fault of all sins. Those [torments, that death] are the words, the utterance of the transgressions belonging to others that I made my own on account of you; this is the roaring of my transgressions, which declares the magnitude of sin.”56

Nadal dwells specially on two of the verba, “Amen I say to thee, this day thou shalt be with me in paradise” and “I thirst.” The former enunciates an effect that is simultaneously rendered in visual form as an exemplary phantasia: in tandem with what imago 129 shows, the words prompt us imaginatively to visualize how Jesus draws the good thief to himself and converts his former disdain into penitent discipleship (see fig. 6). Nadal commands Christ’s crucifiers and with them, all who sin against him, to bear witness to the exemplary benefaction that here transpires before their eyes (Videte rursum vestri consilij exitum).57 It has the power to attract all humankind to Christ, for as Nadal asks, “what sinner is not called, invited, drawn by that merciful example?”58 Focusing on the final phrase, “in Paradiso,” he then discloses how skilled is Christ’s oratory. Jesus utilizes a figure of thought (paradoxon) that takes the form of a figure of speech (antithesis). Abject and crucified, Christ yet demonstrates that his is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, for he elevates and saves the penitent thief. A base sinner is changed into one of the elect, the low is made high: “‘In Paradise.’ What Paradise, Lord Jesus? The celestial Paradise, yet here amidst the depths of the earth. O ineffable sacrament! How worthy of adoration, Christ Jesus, is your power and benignity! Truly it is yours to conjoin the lowest and the highest; man to God, death to life eternal, hell and heaven: in which things your divine mercy shines forth, and your infinite potency is revealed.”59 The power of the figura extends transformingly to the votary, who is urged to apply it to his situation, refashioning himself into a living image of the good thief:

O, holy Lord Jesus, dying you bestow Paradise, wherefore by your death you give access to eternal life, and at the same time cause me in spirit to supplicate as did the thief from the cross. Even more than he, I stand before you, in the sight of my transgression, which you know. . . . Look at me as a friend, reprove me as a son, receive me as a brother. . . . If you grant this . . . I shall hear your spirit saying sweetly in my heart: “Amen, I say to thee . . . ,” and shall feel those words addressed to me in spirit, and your kingdom and immortality initiated [inchoari] in my mortality.60

The verb inchoari (to begin to be spoken) stresses that it is Christ’s verba and, specifically, his figurative usage that brings this effect to life. The elevating grandeur of his words to the thief, which turn upon the allied figures of paradox and antithesis, recall Longinus’s dictum that “figures seem to be natural allies of the sublime and to draw in turn marvellous reinforcement from the alliance.”61 That Nadal must rely upon an extended paraphrasis to tease out the complex workings of this otherwise unnoticed figure identifies it as a special case of the corollary dictum that “a figure is always most effective when it conceals the very fact of its being a figure.”62 This effect, like that of Christ’s words, is both verbal and visual, as Longinus emphasizes by recourse to the simile and metaphor of painting:

sublimity and emotional intensity are a wonderfully helpful antidote against the suspicion that accompanies the use of figures. . . . We see something of the same kind in painting. Though the highlights and shadows lie side by side in the same plane, yet the highlights spring to the eyes and seem not only to stand out but to be actually much nearer. So it is in writing. What is sublime and moving lies nearer to our hearts, and thus, partly from a natural affinity, partly from brilliance of effect, it always strikes the eye long before the figures, thus throwing their art into the shade and keeping it hid as it were under a bushel.63

Equally evident in Nadal’s argument that Christ’s words are directed not at the good thief singly but also at us is the presence in these words of another figure conducive to producing a sublime effect. Longinus describes this figure succinctly as the substitution of one person for another: “Change of person gives an equally powerful effect, and often makes the audience feel themselves set in the thick of the danger.”64

The other example of sublime figuration upon which Nadal expatiates is Christ’s declaration, “I thirst.” Embedded within this short statement is layer after layer of complementarily figured meanings. Most obviously, Christ announces that his every faculty is nearly spent: only the fundamental humor shared by every mortal body (radicalis humor universus), its need for water, is still intact.65 His utterance is also exegetical: it alludes to the prophecy of the Crucifixion in Psalm 21:15–16: “I am poured out like water: and all my bones are scattered. . . . My strength is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue hath cleaved to my jaws: and thou hast brought me down into the dust of death.”66 Additionally, he signals that it is time for the drink of vinegar, placing it among all the other meritorious afflictions he has thus far endured (scis futurum, ut ingratissimum potum tibi propinent carnifices tui).67 And finally, he declares that he is ready now to drink the bitter drink of death, having foreseen it all the days of his life (sitio tamen ipsam mortem, & hunc calicem bibere amarissimum quidem . . . hunc semper prae oculis mentis habui quoad vixi).68 At the same time, he affirms that in accepting this drink, he quenches the thirst for human salvation, making it possible for the water of grace to circulate between himself and humankind: “For indeed, this thirst, whereby I thirst for the salvation and life of mortal men, is most desirable even if most bitter: I call upon them to give me to drink; I fashion out of my life the drink of their salvation, and command that they give me to drink from that water of grace and celestial donation which I produced from out of my thirst and my death. I offer this to all, that they may quench my thirst.”69 This final construal of sitio, by showing how grace comes sweetly to flow from the vinegar of Christ’s Passion, identifies the verb as an epitome of catechresis, a “harsh” metaphor involving the unexpected use of a word beyond its normal sphere of reference.70 The meaning of sitio is elevated, its figurative weight increased, even as Christ’s usage, in formal terms, contracts austerely, consisting of but one single word. This exemplifies how sublimity, though it sometimes arises from figurative amplification, can also proceed from elevating simplicity. Longinus states his case as follows: “The definition given by writers on the art of rhetoric does not satisfy me. Amplification, they say, is language which invests the subject with grandeur. Now that definition could obviously serve just as well for the sublime, the emotional, and the metaphorical style, since these also invest the language with some quality of grandeur. But in my view they are each distinct. Sublimity lies in elevation, amplification rather in amount; and so you often find sublimity in a single idea, whereas amplification always goes with quantity and a certain degree of redundance.”71

Nadal, however, wants also to demonstrate the impressive range of Christ’s sublime oratory, and so he interpolates extended paraphrastic elaborations upon the septem verba, voiced in the first person to show how extensive is the Lord’s command of ornate diction. These paraphrases comply with the Longinian dictum that “the combination of several figures often has an exceptionally powerful effect, when two or three combined cooperate, as it were, to contribute force, conviction, beauty.”72 Take the amplification upon John 19:26–27, “Woman, behold thy son . . .” This passage contains litotes (“neque enim debui etiam absenti meos dolores non significare”), assonance (“Duplices dolores dolui hactenus & doleo, & donec hanc vitam vivam dolebo”), anaphora (“Vidi quae iam inde ab horto passa es, quae nunc patiaris propter me contemplor, & quae passura es donec spiritum emittam”), hyperbaton and anastrophe (“& tamen hos etiam meos de te dolores necessario esse mihi ferendos video, quos ego, ut summa cum amaritudine sentio, ita summa cum animi mei voluntate recipio”), among other figures of syntax.73 It is also replete with figures of thought and speech: in one passage, bitterness of sensation is made to precede the willingness to receive pain (hysteron proteron);74 in another, the relation of acerbitates to patior is reversed by that of patior to cruciatus (chiasmus);75 in this same passage, acerbitates escalate into cruciatus (climax); or again, Christ’s sorrows and torments pierce the Virgin’s soul, “ut gladij crudeles traijciunt,” and then, her sorrows like counterblows cut him to the quick, “traijciunt simul tui meam” (chiasmus);76 in yet another passage, Mary’s presence, rather than consoling her son, instead augments his pain when he descries her great suffering, “tu in has angustias me tradidisti, ut unde mihi dolor esset minuendus, inde etiam augeatur” (antithesis).77 Many other figures are woven into the fabric of Christ’s expansion upon his terse speech, which is thereby shown to be exalted in its simplicity, yet potentially ornatus in the figurative amplification it accommodates. It is thus seen dually to fulfill the Longinian criteria of intensive simplification and figurative elaboration.

The septem verba, then, are epitomes of the sublime, but more than this, they exemplify all three categories of style and function set out by Augustine. Their figurative richness, paradoxically encoded into their simplicity, qualifies them as paragons of the temperate style that pleases even as it compels, by deploying ornaments that seize and sustain attention. Their grandeur and elevating simplicity make them paragons of the majestic style that chiefly aims to move and compel. These same characteristics confer the clarity and instructive force more commonly associated with the subdued style. Indeed, immediately after concluding the first part of his meditation, which stresses how emotionally stirring are the septem verba, Nadal starts over again, this time focusing on their function of instructing souls: “You invested your Passion and Cross, great Jesus, with the divine power of all good things; but in these same words you also offered our souls special and salutary instruction.”78

Nadal explicitly circles back to the question of what makes Christ’s septem verba sublime, soon after considering his final words, “Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.” His death, like other aspects of his person—the immense light of his divinity (lumen esse immensum), his infinite virtue (virtutem infinitam), his sempiternal glory and life everlasting (gloriam & vitam sempiternam)—are sublimia beyond the human capacities of understanding and speech (haec esse supra quam dicere possetis vel intelligere sublimia).79 In spite of this, through such devices as his words from the cross, Jesus allows us to discern the spiritual significance of these mysteries. As they are comprised by the conjunction in him of simplicity of essence and infinity of being, so, Nadal implies, the simplicity and majesty of the septem verba signify spiritually to us his essential sublimity. Nadal apostrophizes the filiae Sion, who stand for all “pious souls” (animae devotae): “And yet you sense the spiritual significance of these dignities of God, which lies in his most simple essence and infinite being [simplicissima essentia infinita & esse]. You acknowledge that you are sustained by these truths [viz., by the sight of Christ crucified and his words from the Cross], supported by them, which is a thing of immense substance and truth: and howbeit, him who is this truth, this substance, you see dying on the Cross.”80 For Nadal, the phantasia of Christ crucified, along with the sublimity of the septem verba, work in tandem to secure for us or, better, in us, a spiritual sense (significationem spiritus) of the sublimely mysterious death of Christ, in which inhere his light, virtue, and everlasting glory.

The Passion, concludes Nadal, is immensely sublime also in its persuasive effect, for it inspires and motivates us, in the Augustinian sense, to do something we may have been reluctant to do—namely, suffer and die for the faith, in imitation of Christ. Here, Nadal is explicitly conflating Longinus’s criterion of sublime thought with Augustine’s linked categories of granditer dicere (De doctrina christiana 4.19.38) and convertere (ibid.), the former formal, the latter functional. His topic is disciplina, the penitential discipline of self-mortification: “But your singular benevolence also teaches us the sublime discipline [sublimem . . . disciplinam]: for you did not expressly commend your spirit to God the Father, until you had brought to completion all your other sufferings, so that death alone was all that remained. For by your prior suffering Sin had been repeatedly slain: whence we are taught repeatedly to bear our suffering, and to mortify our sins: just as death followed upon your Passion, so you merited for us that from our mortifications, there should follow the death of our sins and victory over our passions.”81 The sublimity of Christ’s Passion, exemplified by the forestalling of his final words, “Father into thy hands . . . ,” produces that most sublime of effects—the transformation of the votary into an epigonus Christi. Christ thus demonstrates consummate mastery of the Longinian sublime: “For the effect of genius is not to persuade the audience but rather to transport them out of themselves. Invariably what inspires wonder, with its power of amazing us, always prevails over what is merely convincing and pleasing. For our persuasions are usually under our own control, while these things exercise an irresistible power and mastery, and get the better of every listener.”82

Epilogue

What then of the brief appearance of the term sublime in the Marian appendix, “On the Praises of the Virgin Mother of God”? Nadal’s use of the term here accords with its sphere of reference in chapters 102 and 116, where it connotes the transmission of divine mysteries. The emphasis now shifts, however, from delivery to reception, from the manner of these mysteries’ bestowal to that of their cognition. The topic being discussed, as part of the subsection “The Things Said about Mary Are Said Too about the Church,” is the meaning of Revelation12:2, “And being with child, she cried travailing in birth, and was in pain to be delivered”: “But what means it, that this woman is said to have cried out in labor and felt pain in giving birth? There is need here of sublime discernment [sublimi hic intelligentia opus est]. This crying out belongs to Mary, this labor, this travailing in birth, but neither in her conception nor gestation [of Jesus], or in her delivery [of him]; seek not to find these things in Mary, in whom none is to be found.”83 It is rather in her prosopopoeial bodying forth of the Church that Mary is understood to have cried out and felt the pangs of birth, and furthermore, in the words of Revelation 12:4, to have sheltered her newborn child from the satanic dragon: “Who, pray, cries out? The Church, and through her, Mary. But where? Not in the mystery of Mary’s conception and birth [of Jesus], no, not in these; but in the mystical meaning of the [Church’s] conception and birth of the sons of God, which is expressed by the battle with the dragon and by the perennial conflict waged against the mother and son, against the Church, already from heaven [viz., by Lucifer and the rebel angels]. For Lucifer, in striving against truth and God, strives against Christ, against his mother, against the Church. Christ was specially predestined ever to be in God, in Mary, and in the Church: in and through them, God permits himself and his truth to be embattled.”84 This is an extended metaphor, and as such, an epitome of Longinus’s dictum that “figurative writing has a natural grandeur and that metaphors make for sublimity.”85 The metaphor is presented in Augustine’s quiet or subdued style, to foster “accuracy of distinction,” but it also hearkens back to the majestic style, for the analogy of Mary and the Church (which mobilizes both similitude and dissimilitude) effects a change in the reader, who is thereby persuaded fervidly to venerate Mary, knowing that she represents, even as she transcends (through her participation in the mystery of the Incarnation), a nurturing, threatened, and yet indissoluble Ecclesia.86 The capacity to engage with this highly visual figure of thought, to divine its significance by reconciling and distinguishing between Mary as party to the mystery of the Incarnation and as mystical metaphor of the Church, initiates a kind of subliming operation that secures a fuller understanding of the exalted status of the mater Dei and the mater Ecclesia. Sublimis intelligentia can therefore be defined as the ability to respond to Marian sublimia not only in heart but also in mind and spirit, through a process of conversion that changes the votary into a fervent accolyte of Mary. That the imagery of Maria Ecclesia, being scriptural, issues ab ore Dei, qualifies it as yet another instance of rhetorica divina in the sublime style.