This article situates the gallery spaces of House of Orange palaces in the seventeenth century amidst broader European strategies of display. Starting from the position that interior decorative ensembles speak directly to the identity of the resident, it is argued that Orange galleries can be used as a means by which the agendas and ambitions of the Princess of Orange, Amalia van Solms, can be examined in the absence of direct archival evidence of such practices. Since galleries served different purposes based on location and intended audience, a comparative study of galleries used by the same resident discloses the multiplicity of motives for their decor. A central case study of the gallery at the Stadtholder’s Quarter in The Hague reveals the idiosyncrasy of the space and the personal agendas of the resident, while also making clear the methodological necessity of approaching interiors from an integrated perspective.

Introduction: The Art of Display as Representational Strategy

In the early modern period, artworks and decorative objects communicated vital information about the identity of their owner.1 Collections constructed narratives in tandem with their sites of display, spaces that were themselves central elements in the staging of the identity of the collector. Vincenzo Scamozzi explicitly linked the design of residential buildings with identity in L’idea dell’architettura universal (1615): “Just as we judge a man by his face, these external signs inform us that this is the house of a nobleman.”2 If Scamozzi’s claim is extended to include the arrangement of such signs in an interior, representation becomes an elastic discourse in which any combination of elements that invokes the identity of an individual can be construed as a type of portrait. Identity was not only performative for the subject but also experiential for the viewer, relying on the viewer to assemble and interpret the space and its contents.3 Since early modern elite space was structured around rigid practices of social etiquette mapped onto and enforced by architectural planning, nuances of the identity of the subject were communicated through the experiences granted to the viewer.4

Strategies of display were central to the palaces of the House of Orange. Although the Dutch Republic was governed by the States General, a representative republican assembly, its aristocracy continued to play a notable role in artistic and political life. Galleries built and renovated by the Prince and Princess of Orange in the first half of the seventeenth century at the palaces of Honselaarsdijk and Ter Nieuwburch (among others) were significant aspects of dynastic agendas: they advantageously situated the prince and princess within a European monarchical community to which they did not and could not actually belong while simultaneously aligning them with more local agendas. Princess Amalia van Solms, (1602–1675) seems to have been particularly sensitive to strategies of display in her galleries (fig.1). The gallery in Amalia’s apartment at the Stadtholder’s Quarter in The Hague diverges from the established typology of galleries visible in her other residences. It presented more unconventional and personal connections rather than grand dynastic narratives aimed at a wider public.

The gallery at the Stadtholder’s Quarter in the Binnenhof illustrates how spaces intended for a restricted audience used portraits to promote Amalia’s agendas and to map her social networks separately from those of her husband, Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange (1586–1647).5Isolated attention to Amalia’s apartments prioritizes her role as a patron at a time when her name would not frequently have appeared in textual documentation. Studying female patrons is often hampered by the way in which records were kept and payments were made. As art historian Roger Crum observed about his own family, even though his mother’s decisions dictated the selection of housewares, a future historian would assume that the “patron” was his father, who wrote the check.6 The gendered nature of early modern record keeping has proven detrimental to the study of Amalia van Solms, since little of her agency as a patron is directly documented.7 Such a study is further complicated by the loss of the majority of her household archives.8 By focusing on spaces that fell within the domestic sphere of the princess and contrasting them with both the space associated with the prince and those that were more accessible, some hypotheses about Amalia’s own practices and preferences can be proposed. Her galleries make visible the multifaceted role of the Princess of Orange during a complex moment in Dutch history and simultaneously reveal both Amalia’s actual social networks and the status to which she and her husband aspired.

The surviving inventories of the House of Orange are familiar resources to those interested in elite patronage, offering not only a snapshot of a collection but also a record of a series of spatial experiences.9 Since the majority of spaces are no longer intact and the majority of the art collections have been dispersed, viewing the inventories in a holistic manner allows for broader hypotheses about court space, in both its built architectural and social aspects. This approach follows Daniela Bleichmar’s assertion that “objects in early modern collections cannot be understood in isolation from one another and from the space in which collectors displayed and viewers encountered them.” She argues “for the need for thinking of collections as spaces that constructed narratives.”10By combining the study of collecting with strategies used in architectural history to foreground issues of circulation and access, I suggest that it is at the intersection of the architectural, social, and decorative aspects that Amalia’s collections functioned.

Elite residential spaces across Europe were hierarchically structured, and the access to and functionality of each room reflected the relative social standings of resident and visitor.11 As a visitor penetrated further into a suite of rooms, s/he would encounter spaces that were decorated in accordance with an ever-narrowing audience. By granting or denying visual access to the (sovereign) body, the placement of portraits constructed and maintained hierarchical relationships. The contrast of public sites and Amalia’s personal apartments gives insight into her artistic tastes and practices independent of her husband. In Orange palaces, galleries could be tools of state diplomacy, but they could also reflect the differing tastes and individual agency of their occupants. A comparison of the relatively restricted galleries of the Stadtholder’s Quarter with other Orange galleries reveals the range of functions of a gallery in the Dutch Republic more broadly, while also elaborating on particular aspects of Amalia’s identity as the Princess of Orange and as a patron of art and architecture.

Patrons and Portraits: Frederik Hendrik and Amalia van Solms

Together, Frederik Hendrik and Amalia (fig. 2) forged a new court culture in The Hague, inspired by the examples of Elizabeth (Stuart) of Bohemia, Frederik Hendrik’s youthful experiences in France, the precedent set by Frederik Hendrik’s mother, Louise de Coligny, and the deliberate mimicry of European princely practices in their architectural and artistic commissions.12 Although Frederik Hendrik’s role as stadtholder was reasonably well defined, the role of the stadtholder’s wife was not. The Prince of Orange was a servant of the state and a military leader, but the expectations for his wife had no clear precedent. Increasingly, the House of Orange used artistic commissions to further its own interests: the preservation of the status and influence of the Orange dynasty. Artistic ensembles also helped to clarify, even entrench, Amalia’s role as consort and matriarch in the public consciousness.

Born to a German noble family, Amalia van Solms (1602–1675) came to The Hague as part of the retinue of Elizabeth of Bohemia in 1621, seeking political asylum.13 Amalia was a noted beauty at the court-in-exile and came to the attention of Frederik Hendrik. Following a three-year courtship, they married in 1625. For nearly fifty years, Amalia was a powerful voice in promoting the House of Orange at home and abroad, raising five children to adulthood and arranging their advantageous marriages. The princess was seen by some as essential to diplomacy in The Hague. To gain access to the stadtholder himself, it was often useful to appeal first to Amalia.14 Contemporaries like the British ambassador William Temple even claimed that he knew of no woman with so much ingenuity and so sound a grasp of political affairs.15 Even after the death of the prince in 1647, letters written by ambassadors document Amalia’s ongoing role in international relations.16 She maneuvered on behalf of her favorites, whether playing matchmaker for her children and her sisters, coordinating the education of her grandson Willem III, or ensuring the appointment of her preferred candidates to political and military positions.17 Her artistic patronage has been harder to pinpoint, however. Recent scholarship has taken more seriously her role as a discerning collector as well as an active agent in the management of the couple’s estates, a discussion to which this article aims to contribute in the realm of the strategic use of portraits.18

Portraiture should be taken seriously as a central element in Orange visual agendas owing to the sheer amount of money spent on them by the prince and princess. The transactions recorded in the surviving payment registers of the Nassause Domeinraad demonstrate that portraits were one of the mainstays of interior decoration in the palaces of Amalia and Frederik Hendrik; they made up a large percentage—perhaps as much as a half—of overall Orange artistic patronage of paintings.19 Between 1637 and 1650, consistently large payments for verscheyden conterfeijtsels (assorted portraits) were made to numerous painters, including Gerard van Honthorst, Adriaen Hanneman, and Gonsales Coques.20 However, while portraits depicting Amalia van Solms and Frederik Hendrik have been the subject of some study, the ways in which they displayed and manipulated their collection of portraits has not.21

The way portraits were discussed in letters helps establish the significance attached to where portraits were hung for early modern viewers. For example, Frederik Hendrik indicated in a letter of 1624 that the presence of a portrait of the young Amalia van Solms in his private apartment had prompted salacious gossip. It was not the content of the portrait but the location of the image in proximity to the prince’s private spaces that implied an inappropriately intimate relationship between owner and sitter. 22 By reframing an analysis within the relationship between viewer, the viewed, and the site of viewing and by shifting attention from the portrait as an autonomous object to the portrait gallery as a curated whole, we isolate the owner-collector’s strategies for situating themselves within particular matrices. Portrait galleries actively construct the identity of the resident and stage claims about personal alliance, family allegiance, and artistic patronage.

The Gallery as an Architectural Type

By the seventeenth century, a gallery was a requisite part of a palace, though it was not necessarily consistent in form or function. It served as a space to take exercise in cold weather or speak with visitors away from prying eyes.23 Although such spaces have been widely studied in other national traditions, there has been little discussion of the seventeenth-century Dutch gallery.24 Perhaps this is reasonable: after all, the gallery was an architectural feature particularly associated with royalty and aristocracy. The stately implications and grand size of galleries run counter both to the republican rhetoric of the United Provinces and the space available for building. However, the galleries of the House of Orange reveal how the agendas of the family resonated with European elite practices while navigating conflict with local politics.

The gallery originates in late medieval castle planning. According to Volker Hoffman, the word galerie first appeared in French in a construction document of 1315 to describe an open portico connecting the chapel to the salle in the residence of Countess Mahaut d’Artois at Conflans.25 Resembling a hallway in form, longer than it was wide, the late medieval gallery was a private space, appearing most often as the culminating space in an apartment and not connected to other spaces. For example, at the Hotel Bourbon, built around 1390, the gallery ran along the Seine and played no role in the circulation of visitors through the building since it could only be accessed from the rooms of the duke.26 Barbara Gaetghens, Jean Guillaume, and Sara Galletti have argued that even the Rubens Gallery at the Palais du Luxembourg could only be visited by being escorted through the chambers of Marie de Medici herself.27

By the late seventeenth century, the gallery had been transformed from a space of retreat into a much more accessible space. As the rooms that composed the elite apartment grew more complex, to enhance the prestige of the resident envoys and ambassadors were required to pass through more spaces, and the gallery took on a more public function. This is reflected in both architectural treatises and built examples: Giuseppe Leoncini, writing in 1679, perceived the gallery as the border between the public and private spaces of an apartment.28 In addition to the most grandiose case, the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles, other examples such as the Château d’Anet and Château de Beauregard indicate the public, performative nature of the space by deploying grand architectural elements: stately staircases might deposit a visitor into a gallery or an impressive fireplace might grace one wall.29

The gallery acquired its second aspect as a room for paintings only after its establishment as an architectural type. Even within the tradition of the portrait gallery, there are conventional types of galleries, each with its own unifying theme and purpose. A gallery might demonstrate the erudition and breeding of the resident through the presence of portraits of illustrious or learned men, it might situate the resident within the circle of courtly feminine graces in a gallery of beauties, or it could make visible the ancestral ties from which the standing and legitimacy of the resident derived.30 Although all of these types were utilized in the palaces of the House of Orange, it is the ancestral gallery that is most commonly in evidence. As a tool for staging family identity, it formed what Rebecca Tucker has called “the organizational backbone” of the Orange estate of Honselaarsdijk, the chief architectural embodiment of Frederik Hendrik’s status as landed nobility.31

As a way to lay claim to political legitimacy, female patrons in particular may have stood to benefit the most from portraying their lineage and allies. In the Burgundian Netherlands in the sixteenth century, for example, Margaret of Austria’s residence in Mechelen boasted a long space furnished as a library that also functioned like a gallery, decorated with dynastic portraits and battle scenes.32 As Dagmar Eichberger and Lisa Beaven have demonstrated, the systematic display of family portraits in the more publicly accessible Première Chambre of Margaret’s residence emphasized her legitimacy as regent of the Netherlands.33 The choice of subjects was twofold: portraits functioned as a visual family tree, emphasizing her genealogical right to rule, while images of her allies by marriage and treaty further supported her claim to political agency, a critical tactic at a moment of social change. The display both reflected the reality of the resident and generated a new image of the relationships that she had actively sought to cultivate. The dual function of the gallery for a female patron demonstrated by Eichberger and Beaven serves as a powerful parallel for the later Dutch case.

The Stadhouderlijk Kwartier

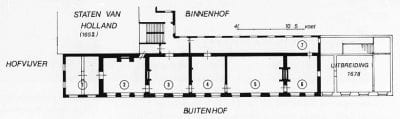

The Stadtholder’s Quarter (Stadhouderlijk Kwartier) in The Hague was distinct from the other spaces inhabited by the prince and princess (fig. 3). The building itself was the property of the States General and a suite of rooms at the heart of the seat of government was traditionally placed at the disposal of the stadtholder.34 The rooms inhabited by Frederik Hendrik and Amalia would not have previously accommodated female residents, since there had been no princess of Orange during the stadtholdership of Maurits, his unmarried predecessor. Alexander le Clerq and controlleur Jan Herwouters inventoried the rooms in 1632.35 This inventory is the first surviving document to record rooms decorated specifically for, or arguably by, Amalia van Solms. It stands as an early marker of Amalia’s ambitions, since in 1632 the couple was still establishing their artistic policies and prestige. The galleries at the Stadtholder’s Quarter are also, paradoxically, the most private of the galleries they commissioned, despite being in their most “official” residence.

The galleries in the Stadtholder’s Quarter are seldom discussed in the literature on Orange portrait practices. Tucker asserts that it is distinct from other palaces built by Frederik Hendrik and Amalia as it is the only residence lacking a clearly defined portrait ensemble. In her view the decorative scheme spoke to artistic rather than political agendas. She attributes this potentially to the fact that the prince and princess did not own and plan the space since it functioned merely as their state rooms. She suggests that it may have been inappropriate for them to make grand claims about lineage in such a space.36 While Tucker is correct in identifying the galleries as lacking a unifying theme consistent with the pan-European typology of galleries discussed above, the very fragmentation of standard decorative schemes makes a distinctive artistic agenda more visible.

The earliest section of the Stadtholder’s Quarter was built primarily in 1620 and constituted a long set of rooms in nine bays extending thirty meters from the five-story tower built by Maurits at the corner of the Binnenhof.37 The wing had a cellar, a ground floor, and two levels of living spaces, with the prince housed on the first floor and Amalia above (fig. 4). In 1632, the year of the inventory, these rooms were lengthened on the Hofvijver side of the tower. The inventory is specifically dated to August and was most likely made after the expansion, since it refers to “new” rooms in the apartments of both the prince and princess.38 Although the inventory records what type and how many rooms were in use, the precise floor plan of the apartments in 1632 is unclear since a fire in 1635 prompted renovations that lasted at least into the early 1640s.39 The inventory walks the reader through connected spaces, even commenting on connecting passageways with relatively little in them. Although it is impossible to make definitive conclusions based on the rooms listed in the inventory (the writer does not record, for example, stairs), movement from one space to the next seems to have been consistent with broader European spatial practices.

The prince’s chamber presents a typical arrangement of rooms in keeping with the spatial practices of French and Italian residences: his more private rooms in the Mauritstoren and the 1632 extension included a garderobe, a small “chamber,” and a bedroom. These connected to a more formal set of rooms in the 1620 wing consisting of two voorkamers, an audience or reception room, a cabinet, and a gallery.40 While the first four rooms were all aligned along the Buitenhof, the gallery ran the length of the rooms on the “inside,” facing the Binnenhof. In the inventory, the relatively secluded cabinet preceded the gallery. According to Konrad Ottenheym’s 1993 reconstruction, the gallery connected both to the stairs and the prince’s cabinet, suggesting a range of uses.

Access to the gallery appears more restricted on the second floor where the princess lived. The inventory indicates that Amalia had two “cabinets” in her apartment, both significant spaces. The first was decorated with Turkish carpets, a Rubens painting over the mantelpiece, and other expensive furnishings. The second cabinet, the culmination of the formal rooms, held even more luxurious materials: gold leather wall coverings, mirrors, and Japanese cabinets. The gallery, above that of the prince, is preceded in the inventory by a cabinet termed “the cabinet of the Princess of Orange between the two galleries,” making the linking of spaces explicit.41 Access to the gallery, like that of Marie de Medici at Luxembourg Palace, was only through the restricted spaces of Amalia’s chambers. This suggests that it was a space of retreat and controlled access.

The galleries of the prince and princess were identical in shape and size, were clad in similar tooled and gilded leather wall coverings, and had matching Honthorst mantelpiece-paintings depicting shepherdesses.42 However, the broader decorative schemes reflected different preferences. The prince’s gallery held a wealth of paintings, including landscapes, religious scenes, and nymphs painted by Honthorst,43 and a Moses by Pieter Lastman,44 as well as paintings by Cornelis van Poelenburgh, Pieter Bruegel, and Antony van Dyck. Altogether, there were fifty-four paintings in the gallery, all overseen by a mantelpiece-painting of Diana with a shepherdess and two winds by Honthorst. However, there were only four portraits: his parents, Willem the Silent and Louise de Coligny; his esteemed guest Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia (fig. 5); and his wife, Amalia van Solms.45 His preferences were otherwise courtly and allegorical subjects, a trend consistent with inventories of his chambers at other palaces. Amalia’s gallery, on the other hand, was dominated by portraits: there were no fewer than nineteen portraits in that room alone, not to mention the numerous portraits found elsewhere in her suite. The sitters for the portraits in the gallery included her son Willem II and two of her daughters; twelve paintings of the queen and eminent lords of France; the marquises of Verneuil and Marmontye; the Countess of Bouillon; and “Mevrouwe Stranges.”46 There is no unifying theme to these portraits consistent with the typologies of portrait galleries. Why then were these paintings selected, and what statement were they making about Amalia?

Comparative Cases: Oude Hof at Noordeinde, Huis ter Nieuwburch, and Honselaarsdijk

Before analyzing Amalia’s gallery, we should consider the possible models for such spaces available to her in The Hague. Directly following her marriage in 1625, she temporarily lived in the Oude Hof (Noordeinde), which was later inventoried in the same document as the Stadtholder’s Quarter. The previous resident, Amalia’s mother-in-law Louise de Coligny, had taken up residence in the Oude Hof following the assassination of her husband Willem the Silent in 1584 (fig. 6). Although she ultimately died in France in 1620, the rooms she inhabited in The Hague were clearly associated with her at the time of our inventory, some twelve years after her death. Her apartment included a voorsaele, a reception area termed de groote benedensael, a camer used for receiving visitors (here titled De camer daer mevrouw de princesse hoochl mem. plach te logeren), a cabinet (directly following in the inventory, titled Het cabinet van tselve quartier), and a gallery. The gallery’s appearance in the inventory after the garderobe invites comparison with other examples noted above where the gallery is a space of retreat and limited access.

Louise made her social and dynastic alliances visible in order to strengthen relationships. The portraits in her cabinet were her closer relatives, including her grandmother Louise de Monmorency, her parents Gaspard II de Coligny Chatillon and Charlotte de Laval, and some of her stepchildren.47 Notably included was Louise Juliana, daughter of Willem I by his second wife, whose marriage to the Elector Palatine Frederik IV may have been brought about through the intervention of the diplomatic Louise de Coligny herself.48 Continuing into the gallery, the subjects of the portraits shifted, instead representing a broader network of family and social alliances that stretched across Europe.49 The portraits functioned in two ways: they reflected existing relationships and they attempted to cement newer connections. While portraiture established her personal connections through the inclusion of her relatives, more importantly, it tied her visual identity to the very highest European nobility through the inclusion of crowned heads of state, including Henri IV of France, Louis XIII of France, and James I of England alongside her own portrait.

As Jane Couchman has proposed in an analysis of Louise’s epistolary practices, her letters functioned as a conscious, visible reminder to relatives of the plight of the widow and her children, and of the (financial) responsibilities of those relatives to the struggling family. Couchman argues that Louise’s extensive letter-writing activities “brought her from virtual isolation in the Netherlands . . . to a position of considerable influence within the context of an affectionate and often admiring family.”50 These epistolary practices directly parallel the relationships reflected in her selection of portraits. This particular set of portraits made a strong statement about how she wished to be perceived.

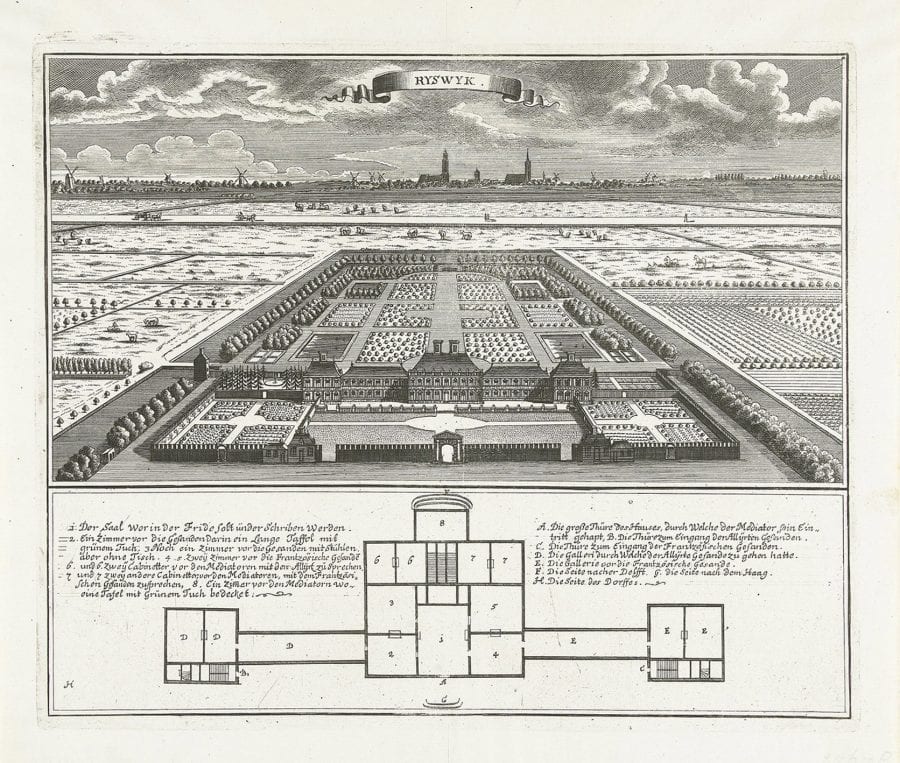

Elsewhere, too, Frederik Hendrik and Amalia used the galleries in their palaces to stage similar narratives. At Huis ter Nieuwburch in Rijswijk (fig. 7), the galleries built visual and spatial associations through strategic placement of portraits. The palace was built as an entirely new construction on land purchased by the prince in 1630; it became known for its claims to originality rather than renovation.51 The building consisted of a central pavilion connected via galleries to the chambers of Frederik Hendrik in one direction and Amalia van Solms in the other. The decoration of the space cannot be discussed in precise detail, since not only was the palace razed but contemporaneous inventories are fragmentary.52 Though H. H. Heldring and Marieke Spliethoff argue that the galleries consisted exclusively of portraits of European monarchs accompanied by allegorical scenes, it is hard to say with certainty who was represented in these galleries. Scholars have generally agreed that one document written in Frederik Hendrik’s hand likely provides the identities of the sitters, and if that is the case, Amalia and Frederik Hendrik associated themselves visually with the very highest levels of European nobility.53

The portrait galleries at Rijswijk were the dominant architectural elements in the progress of a visitor through space. When visiting the house, a guest entered through the central pavilion and passed through a main salle, where a life-size double portrait of Frederik Hendrik and Amalia by Gerard van Honthorst hung over the fireplace (see fig. 2).54 A visitor then proceeded through the gallery to the rooms of the resident they wished to visit. Portraits of male rulers lined the gallery of the prince’s wing, while female rulers appeared in the gallery approaching Amalia’s rooms.55 By forcing the visitor to process past images of the queens and princesses of Europe to arrive at the chambers of Amalia van Solms, the unknown designers of the decorative scheme effectively inserted the princess into the elite coterie of women represented in paint on the walls. The architecture and the decor insist that a viewer consider the House of Orange in such august company.

Rebecca Tucker’s analysis of Honselaarsdijk provides the most elaborate comparative example of sites of portrait display. At Honselaarsdijk the Prince of Orange built a palace of sophistication unparalleled in the Dutch Republic. West of The Hague, it was the location of the ancient castle of Honsel, which had been the property of the counts of Aremberg.56 The renovation and decoration of Honselaarsdijk remained a central interest of the prince throughout the 1630s. As Tucker has argued, the palace was a critical component of the stadtholder’s image as a nobleman.57 The galleries included both dynastic statements and galleries of worthies, though the selection of sitters was more dynastic and less learned than other comparable examples.58 Although the seventeenth-century inventories are inconclusive, accounts from the visit of the Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin in the 1680s make it apparent that the prince’s audience rooms were reached by traversing a gallery filled with portraits of the crowned heads of Europe, echoing the sequence at Huis ter Nieuwburch and the Oude Hof.59

The palace in its entirety stressed the elite identity of the residents and was deeply invested with the formal, pseudo-monarchical aspects of courtly life. The galleries thus likely resembled comparable galleries at the palaces of other European monarchs into which the Prince and Princess of Orange had worked to insert themselves. In 1631, Frederik Hendrik and Amalia sent a pair of full-length portraits to Charles I of England, with whom they hoped to build a stronger relationship. The portraits first appear in an undated inventory kept by Abraham van der Doort, where he recorded that they were hung together in the Bear Gallery at Whitehall.60 Such a placement situated Charles visually amidst those he regarded as his allies and equals: it held at least thirty other portraits, including the king of Spain, Henry IV of France, Charles V, James IV of Scotland, Queen Ann, and Marie de Médicis. Jerry Brotton sees the decoration of the Bear Gallery as a means for Charles to communicate his lineage, his legitimacy, and his personal loyalties.61 It is precisely in this manner that the Orange galleries also functioned.

Interpreting the Stadtholder’s Quarter:

When compared with Whitehall, Honselaarsdijk, and Ter Nieuwburch, Amalia’s gallery at the Stadtholder’s Quarter seems even more unusual. Amalia’s rooms were, as Tucker noted, inconsistent with other residential spaces of the House of Orange. Yet that very inconsistency merits further analysis. A visitor invited into the gallery in 1632 would have experienced a space with no parallel at other palaces. Although there is no documentation to confirm who selected the images for the gallery, if the decor was planned as an ensemble, or how precisely the paintings were arranged, the nature of the images suggests the involvement of the princess herself. Given the relative obscurity of Amalia’s agency during these years, any indication of her patronage should be exploited to advance understanding of how her court functioned.

Amalia’s gallery held more portraits than the corresponding space in her husband’s apartment, suggesting a preference for portraiture. The specific sitters in the portraits reflect Amalia’s personal and familial objectives. At the time of this inventory, Amalia’s chief concerns were the promotion of her own role as wife of the stadtholder, her influence owing to that position, and the social standing of the family. The least surprising portraits in her gallery are the paintings of her children, represented by two examples. The first depicts the very young Willem II nude and leading a leopard by a ribbon accompanied by two of his sisters; Marieke Spliethoff identifies this with the Honthorst portrait recently returned to Apeldoorn (fig. 8).62 Consistent with Amalia’s courtly tastes but unusual for elite portraiture, a historiated portrait of the nude prince would likely only be hung in a private space. The second portrait again emphasizes Amalia’s pride in producing a male heir for the Orange dynasty, as it represents Willem II by himself.63 The birth of a male heir had coincided with an increase in popular support for the Orangist faction and reinforced her social and dynastic significance.

Other portraits on the walls in the Binnenhof stand as evidence of Amalia’s keen understanding of the need to map her network of relatives and connections. At the outset, the collection seems consistent with the francophilia seen elsewhere in the patronage of the prince and princess: the queen and the elite of France were represented in twelve portraits. This selection of portraits made visible Amalia’s desire to be counted among such company. However, given the comparatively private nature of her gallery, its primary function was not about broadly aimed statements of political status and influence. Instead, she chose portraits that gave evidence of her relationships with women who played unusual but significant social roles. These included “Mevrouwe Stranges,” the Hertoginne of Bouillon, and the marquise de Verneuil. In the absence of any existing study of letters written by Amalia, analyzing her portrait collection provides a better understanding of female court dynamics.

The first of the idiosyncratic relationships documented by the portraits in the gallery is that of “Mevrouwe Stranges,” referring to Charlotte de la Trémoille. A granddaughter of Willem I, she married the seventh Earl of Derby and later played a significant role in the English civil war.64 Charlotte had known her uncle Frederik Hendrik since her childhood, noting in a letter of 1609 that he had given her New Year’s presents.65 In 1626, she was in The Hague during the negotiations surrounding her marriage. Indeed, it was in The Hague in July of that year that her marriage to James Stanley, Lord Strange took place.66 Following her subsequent move with her husband to England, she appeared briefly as a lady in waiting at the court of Queen Henrietta Maria and was therefore privy to court activity. Perhaps more relevant was her return to The Hague in the spring of 1632.67

The painting of Charlotte listed in the inventory of Amalia’s gallery has been identified as a panel by Gerard van Honthorst, now in the Dutch Royal Collection, which shows Charlotte dressed as Minerva (fig. 9).68 Not only was the historiated portrait very much in vogue in the early 1630s, but most of the comparable traceable historiated portraits of Amalia van Solms were owned by close female associates.69 Amalia’s choice of this type of portrait in her gallery strengthens the visual tie between the two women. Their relationship is further signaled by a work most likely commissioned for Honselaarsdijk in which the two women are portrayed together on the same canvas in the guises of Diana and a nymph (fig. 10). Amalia’s ownership of multiple portraits of her husband’s niece speaks to the coterie of young aristocratic women present at The Hague court in the 1630s. Moreover, the commissioning of a copy by Charlotte and her husband for display in their own home would have visually strengthened the connection in the eyes of foreign audiences as well. 70

A second unusual portrait in the gallery represented the “Hertoginne van Bouillon,” Elizabeth of Nassau, daughter of Willem I, and therefore the half-sister of Frederik Hendrik. In 1595 she married Henri de la Tour, duc de Bouillon and marshal of France. Their marriage was one of alliance between the French Huguenots and the Protestant United Provinces. Elizabeth had even sent her son to learn the art of war under Maurits, Prince of Orange and Frederik Hendrik’s predecessor, much as Frederik Hendrik himself was sent to the court in France. This reflects the cultivation of close relationships between the children of Willem I that continued well into the seventeenth century. In addition, Elizabeth’s husband was the leader of the French Protestant faction, a useful political tie for the Dutch Republic to cultivate.71

The presence of Elizabeth of Nassau and Charlotte de la Trémoille in Amalia’s portrait gallery suggests that these noble women formed their own informal networks of exchange, channels through which favors and information could flow. In a fashion similar to the networks displayed by Louise de Coligny and supported through letter writing practices, both of these women are to be found in Elizabeth of Bohemia’s letters to Sir Henry Vane, written from The Hague during 1632. Elizabeth often mentions the women in contexts that suggest they served as unofficial channels for the transfer of information. In a letter of April 22, 1632, Elizabeth states “By the next you shall haue all the newes out of England by my Ladie Strange if the winde holde.”72 Elizabeth also noted that both Elizabeth of Nassau and Charlotte de la Trémoille were in The Hague by May 6, at which point they became godmothers to Isabella Charlotte of Nassau, further strengthening their bonds with the Dutch elite.73 The tone in which Elizabeth discusses the women suggests that they were intimates, up to date with the daily events at court in both the Dutch Republic and England. The presence of their portraits in Amalia’s gallery suggests a similar relationship, except that Amalia also had the leverage of closer family ties.

The third and most perplexing portrait depicted the marquise de Verneuil, Henriette Balzac d’Entrangues, a figure with no apparent connection to the House of Orange. Born in 1579, she became the mistress of Henri IV and even extracted a written promise of marriage from him should she give birth to a son.74 She is described as quick of wit and charming of manner. All accounts also depict her as single-mindedly fixated on becoming the queen of France, despite Henri’s marriage to Marie de Médicis in October 1600. She was ultimately implicated in conspiring against Henri and died in 1633. Why precisely Amalia van Solms owned her portrait remains unclear, but we might surmise either that it represents some otherwise undocumented connection or that the inventory was in error. It is also possible that Henriette was known to the prince from the time he spent at the court of Henry IV. All three women in these portraits were active in their own local politics, maneuvering to protect and advance family agendas. Elizabeth had been serving as regent of her deceased husband’s territory and traveling extensively in the company of Charotte de la Trémoille, while Henriette managed to secure a marquisate for herself through her manipulation of Henri IV. Could Amalia have been aware of the extent of their activity and regarded them not only as relatives but also as allies?

Amalia’s gallery thus makes visible a narrative in which her sphere of influence stretched into the past through lineage (both social and familial), connected with other notable contemporary women, and looked into the future through her descendants. Her gallery reflected her pride in and affection for her children, as well as her connections to other women. It stands in stark contrast to the galleries found in other Orange palaces, which, lacking the relative seclusion of this space, highlight for her a more depersonalized role as consort. The galleries at the larger palaces were spaces in which she had little demonstrable agency due to their conventional structure. Rather than any individual object, it is precisely the unconventional combination of images, styles, and sitters in her gallery at the Stadtholder’s Quarter that suggests her personal involvement in selecting and displaying the paintings. This is furthered by the presence of other art objects and decorative elements including the porcelain that she collected so avidly.75 The gallery at the Binnenhof makes evident the necessity of Bleichmar’s proposition: we must consider the contents of a room as a whole to truly understand the impact of any individual object.

Conclusions

As Marten Delbeke observed about Barberini palaces, “[the gallery] aims to produce a continuous and unified narrative out of a diversity of objects by creating a coherent and attractive visual display . . . the gallery invites one to see both the object and its framing.”76 By applying this insight to Amalia’s gallery, we see that, individually, the portraits hung there may not have represented the highest levels of society or been consistent with her decorative choices elsewhere. However, when we consider the physical and conceptual framing of the gallery as a whole, the portraits contribute to a unified ensemble that reveals a different aspect of the princess. They presented a network that spoke to the agendas and audiences of the gallery’s decorator. Each aspect of Amalia’s identity—as wife, ambitious consort, courtier, or mother of a dynasty—was dependent on the specific site of display. In galleries more clearly associated with formal state functions, Amalia was presented solely amidst queens and consorts. In her own less accessible chambers in the Stadtholder’s Quarter, she saw herself at the center of a network of familial and female alliances.

By reconsidering the contents and accessibility of the gallery at the Stadtholders Quarter, this essay has shown how portrait galleries can provide a rich resource for understanding networks of influence. Approaching portraits within their sites of display allows us to understand the spaces themselves as critical components of the reception of the portrait, even in the absence of the specific portraits that were displayed. The variety of relationships visible in her gallery is both evidence of and witness to Amalia van Solms’s activities as a patron and collector.

But more remains to be done. Although it is beyond the scope of this essay, the recent digitization of numerous letters written by early modern women will allow future historians to bring knowledge of more social and family networks to bear on art historical undertakings. Although much of Amalia’s own correspondence has been lost, more than two hundred of her letters are now digitally available to scholars.77 This resource opens doors for new fields of study surrounding a woman who worked tirelessly to promote the interests of both the Orange family and the Dutch Republic. Through parallel examinations of her letters and her surviving artworks and decorative objects, future scholars may be able to make explicit what has long been elusive: the breadth and depth of the cultural and political agency of Amalia van Solms, Princess of Orange.78

Appendix of Inventory Transcriptions

Taken from: http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/retroboeken/inboedelsoranje/ – page=221&accessor=toc&source=1

Footnote 45

Item 45. een schilderije van Prins Wilhelm hoochl mem., staende in een ebben lijst

46. een schilderije van mevrouwe de princesse hoochl mem. In een ebben lijst

47. een schilderije van de coninginne van Bohemen met den hangende hayre

48. een schilderije van Haere Excie Mevrouwe de princesse met den hangende hayre

Footnote 46

Op de galderije van mevrou de princesse

229. een schilderije van prins Willem ende twee jonge princeskens leydende eenen tijger,verciert met verscheyde fruiten. 245. twaelff contrefeytsels van de coniginne ende groote van Vranckrijk, verciert met geslepe steenkens.

246. twee stucxken, het eene de marquise de verneul end het ander marquise Marmontye.

247. een contrefeytsel van de hertoginne van Bouillon

248. een contrefeytsel van mevrouwe Stranges op de maniere van Palas off Minerve

249 een contrefeytsel sonder lijst, d’effigie van…

250. het contrefeytsel van ‘t prinsken Willem sittende op tapijt.

Footnote 47

Het cabinet van tselve quartier:

517. een kleyn schilderijken d’effigie van Louyse de Monmorency

518. een schilderike, d’effigie van de princesse de Condé.

519. een toevouwent schilderie daerin d’effigie van d’admirael de Chastillon ende zijn gemael.

520. vier kleyne schilderijkens met platte bonnetten op het hooft Fransche heeren, ons onbekendt.

521. een schilderije, d’effigie van de Rijngravinne.

522. een schilderij van den hertoch van Buckingham.

523. een schilderij van den marquis Spinola.

524. een schilderie van den grave van Holland

525. een schilderie van den ambassadeur van Engelandt, millord Vahne.

526. een schilderie van den cardinael van Richelieu.

Footnote 49

De galderije van ‘tselve quartier.

589. een schilderije zijnde effigie van den admirael Chastillon

590. een schilderije, d’effigie van den cardinael Chastillon.

591. een schilderije zijnde d’effigie van d’Andeloo (Francois de Coligny)

592. een schilderije van Hendrick de Borbon, coninck van Vranckrijk.

593. een schilderije van Louys, koninck van Vranckrijk.

594. een schilderije van den hertoch van Bouillon.

595. een schilderije van d’hertoginne van Swartsenburch (sister of Willem 1)

596. een schilderije van de princess van Orangien hoochloffelijker memorie.

597. een schilderie van den prince van Conde

598. een schilderie van Mons. De Chastillon.

600. het contrefeytsel van Jacob, coninck van Engelandt.

601. het contrefeytsel van prins Phillips

602. het contrefeytsel van den graeff van Hohenloo.

603. het contrefeytsel van den hertoch van la tresmouille in ‘t geheel.

604. het contrefeytsel van de marquise de Mirbeau

605. het contrefeytsel van de paelsgravinne van den Rhijn

606. het contrefeytsel van den prins van Walles

607. het contrefeytsel van Henry de Valois, Koninck van Vranckrijk

608. twee kleyne contrefeytsels vanden prins van Conde, vader ende soon.

609. een van de graeff van Soison.