This historiographical essay explores the ways in which scholars—both historians and art historians—have studied the production of and trade in textiles in the early modern period in quantitative and qualitative ways. It discusses not only how textiles were a critically important commodity for both the English and Dutch East India Companies but also how a digital, data-driven approach can enhance our understanding of this complex trade.

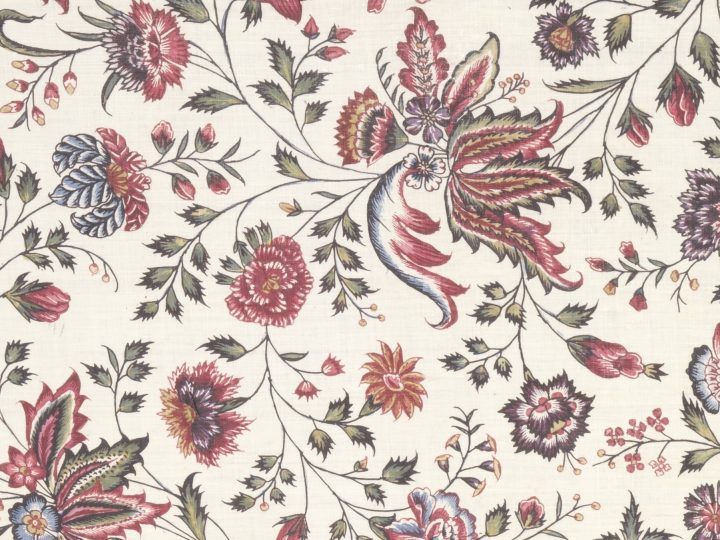

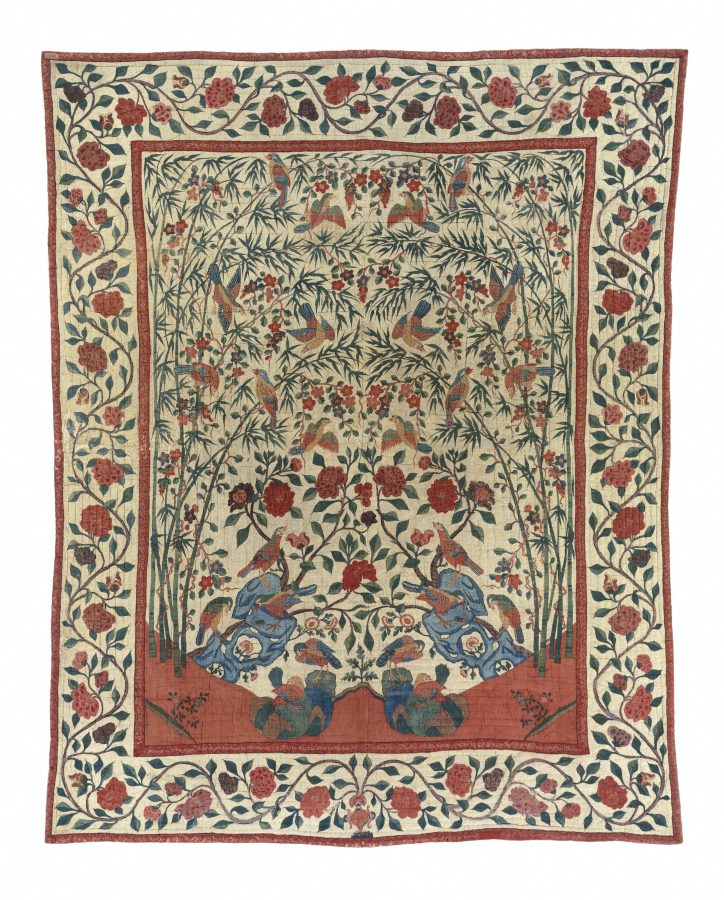

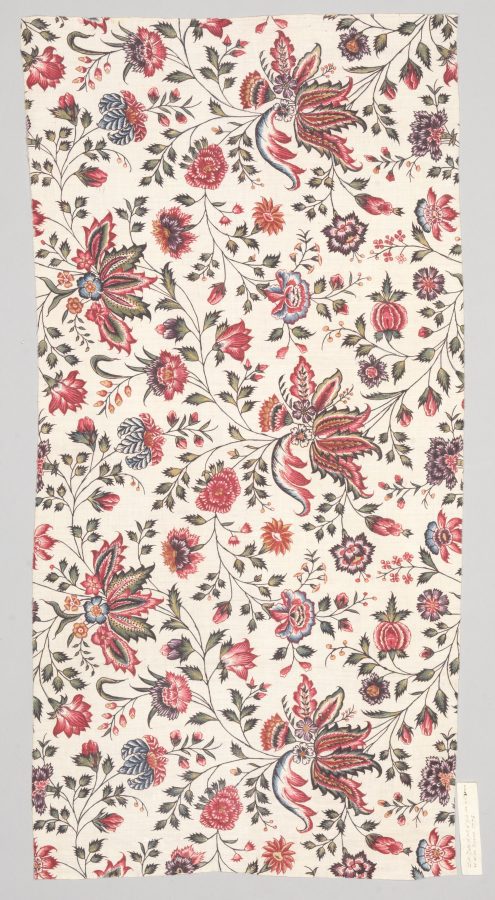

The 2017 exhibition entitled Sits (“chintz” in English) at the Fries Museum shed light on the lasting aesthetic appeal of this popular Indian-made textile.1 Understandably, the exhibition focused on one of the most beautiful and colorful varieties of Indian textiles: chintz, a high-quality luxury product. Notably, however, the Dutch traders and consumers featured in this exhibition were relative latecomers to this specific commodity. Only an understanding of long-distance trade can help us understand how sits became a prominent feature of the traditional Frisian woman’s costume, as highlighted in this exhibition (see, for example, figure 7 in Sylvia Houghteling’s essay in this issue).2 Sold by merchants from all over the world in American, African, and Asian markets, Indian textiles of many types commanded a global market long before Europeans became involved in this trade from the 1550s onward (figs. 1 and 2). For historians, examining European participation in the Indian textile trade provides insight into the social and technological ramifications of this larger network of global trade. It is no wonder that these textiles are the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s object of study.

This essay introduces the major issues, questions, and literature of textile history from the perspective of (economic) global history instead of art history. Broadly speaking, a historian makes sense of this trade by attempting to understand the historical context of the great variety of traded textiles mentioned in primary source documents. In contrast, an art historian takes artworks as their starting point, using historical documents, archives, extant textiles, and knowledge of artistic production to understand how these images and objects have generated meaning over time.

Despite their different approaches to textile history, both historians and art historians agree that Indian textiles were widely diffused among consumers from all layers of Dutch society in the eighteenth century. As we have seen, museums in the Netherlands tend to focus on sits, or chintz, which was a colorful variety integrated into the traditional clothing of Frisian women in the Netherlands. Extensive remaining examples of such garments and their representations in illustrations of that time make it clear that Indian textiles were incorporated into traditional clothing by women at all layers of Frisian society (figs. 3 and 4). Indian textiles were also present elsewhere in Dutch fashion: Anne McCants, for example, has studied the diffusion of Asian commodities in Amsterdam and its surroundings. She found traces of Indian textiles even in the probate inventories of the poor.

Historians might find inspiration in such interesting overlaps with art history, but their object of study is not an image of a textile or the textile itself, but rather the archival trade records that document the circulation of textiles. This is where the trouble starts for historians. These documents shift the attention away from tangible objects and people represented in museums to the more abstract perspective of global trade. The archives of the European East India companies that traded these textiles to Europe and within Asia mention a wide variety of Indian textiles far beyond chintz, and only rarely do these documents give us samples or illustrations of any of these textiles. There are hundreds of textiles with different names and subvarieties that were brought to the Atlantic market or were traded in Asia by European companies. All these names represent textiles with differences in fineness, fiber, and ornamentation, such as the way they were painted or printed in different colors and with different designs. Most of these historic textiles have left no physical trace, so we have to depend on limited written or pictorial sources to know what fiber they were made of and what they might have looked like. Historians are therefore left mainly with written records of quantities, qualities, and prices but little in-depth knowledge of the actual textiles behind these numbers, a problem made more challenging by the inconsistency of written archival descriptions of textiles. The situation is further complicated by the setup of European workshops that printed cottons or mixed fabrics, which—although usually of a lesser quality than Indian textiles—were also often called sits or chintz. In the case of the Dutch Republic, this industry was successful from 1650 onward, but went into decline after around 1765.3 Consequently, the initially straightforward story of the beautiful textiles in museum collections morphs into a complex story that is hard to understand and difficult to bring to life, although historians certainly have tried and succeeded in doing so.

Historians have moved beyond the national discourse of the consumption of Indian textiles only within the Dutch Republic, demonstrating that Dutch traders were indeed catering to a global market. For instance, merchants traded Indian textiles to obtain enslaved people in Africa and spices in Southeast Asia. All of these topics have received scholarly attention, which has helped to situate the textile trade within global networks.4 Many studies have ignored the great variety of Indian textiles in written sources in order to analyze prices and quantities, which is indicative of the way economic historians approach these issues via agglomeration—whereas art historians are more likely to emphasize particularity. In order to avoid this trap, several authors have tried to compile lists of textiles with definitions. In his classic book on the English East India Company (EIC), K. N. Chaudhuri gives a list of textiles’ names and their definitions derived from EIC archival sources.5 Ruurdje Laarhoven has done the same in her dissertation on the Dutch East India Company (VOC) trade in Indian textiles with Southeast Asia.6

Such attempts are often based on archival sources of individual East India companies, like the English or Dutch ones, although links have also been made to museum collections and a wider palette of source material. For example, the Europe’s Asian Centuries project, based at Warwick University, published a new list of definitions in 2012, with documents and material samples where possible.7 This time the research was not just based on the archives of one particular East India company, but rather on several companies and other source material in different languages, such as contemporary dictionaries of trade. The research team also consulted scientists and museum curators. Colette Establet’s Répertoire des tissus indiens importés en France entre 1687 et 1769 (2017) is an even more recent example of a similarly successful attempt to connect names to remains of Indian textiles.8 Also useful are the annual VOC and EIC order books from Asia, which indicate how people defined and envisioned these textiles. This research has been insightful, but even individual textile varieties substantially change over time—a conclusion Femme Gaastra had already reached in 1996, in his work on the impact of European fashion on the appearance of Indian textiles imported by the Dutch East India Company.9 The Dutch Textile Trade Project stands on the shoulders of these foundational projects, further advancing the study of historic textiles.

If historians and art historians want to arrive at new questions, they will need to understand the rich variety of Indian textiles. There have been several efforts to understand this diversified and complex market, but differences exist in the methods and sources used to quantify varieties imported into Europe. First, Sergio Aiolfi used the definitions and statistics from Chaudhuri to calculate the proportion of white and colored textiles imported into Europe by the English East India Company. He concluded that the great majority of imported textiles were white and not beautifully adorned and colored.10 More recently, my own work has focused on eighteenth-century English customs records—which specify the textile types that were allowed entrance into England—in order to calculate the proportions of white, muslin, and colorful (often prohibited) textiles included in EIC and VOC imports. The VOC preferred and obtained colorful textiles, while the EIC increasingly purchased white textiles and muslins. The larger price rise in white textiles and muslins shows that competition for these uncolored textiles was fiercest.11

It is only when all this work has been done that historians and art historians can move on to the big debates about textiles. One position long held in textile history has argued that the Industrial Revolution was a revolution of production followed by a revolution in consumption. The fact that long-distance trade with Asia already provided access to these essential products well before the Industrial Revolution gives credence to the argument that the Industrial Revolution found its origins in an upsurge in consumption, turning on its head the traditional reasoning.12 However, Aiolfi’s work, and my own, additionally suggest a process of import substitutions as competition for white calicoes to be printed in Europe resulted in higher prices and scarcity. In the context of Dutch trade, the intra-Asian trade in Indian textiles generated profits for the Dutch East India Company, since Asian consumers—especially in the spice-rich Indonesian archipelago—preferred beautiful Indian cottons (used in religious ceremonies) over silver in exchange for spices. Laarhoven has demonstrated a decline in the textile trade as the eighteenth century proceeded, leading to a process of import substitution toward locally produced batiks, or colorfully printed Indonesian cotton textiles, in the middle of the century.13

Economic historians have long been concerned with the relationship between the arrival of Indian textiles in Europe and the Industrial Revolution in England. The connection seems quite obvious at first sight: British manufacturers reproduced an already existing commodity—Indian textiles—in all its facets, namely in fiber (cotton), low price, beauty, durability, and washability, seizing the opportunity to replace Indian textiles in an already existing global market. They were only competitive if they used powered machinery. Giorgio Riello and Prassanan Parthasarathi have drawn a two-step connection between the trade in Indian textiles and the onset of the Industrial Revolution. First, European manufacturers wanted to make their textiles as beautiful as Indian textiles by trying to improve their methods of textile printing. Next, they embarked on the mechanization of the production of textiles (the more traditional view of the Industrial Revolution).14 Parthasarathi further argues that explanations for the Industrial Revolution that focus on demand and supply of spun thread in England are in fact a concerted effort to write the connection to Indian textiles out of the explanations of the Industrial Revolution.15 Joseph Inikori has similarly claimed that the demand for textiles in Africa and the English inability to supply these textiles for the African market were responsible for the Industrial Revolution.16 John Styles and Beverly Lemire have provided more sophisticated accounts of the popularization of cotton textiles in general, which highlight the shift from Indian-made textiles to textiles produced in England.17 Some of these studies allow room for connections to the Dutch trade in Indian textiles, including Dutch import substitution through the development of a textile printing industry in the Dutch Republic during the later seventeenth century. However, in large part these findings are particular to the path-dependent development of England toward the Industrial Revolution.

The Dutch Textile Trade Project’s interactive web applications will help us ask new questions about the early modern textile trade and also help give better answers to our old ones. Especially promising is the possibility that these data and applications will give us more clarity about the different varieties of textiles. Apart from distinguishing between varieties, it will also allow a better understanding of the destinations of these varieties of Indian textiles. In any case, Sergio’s Aiolfi’s distinction between white and colored textiles has served its purpose, as we need a more nuanced distinction between fabrics. Hopefully, this new understanding of the great variety of textiles will help us to understand better the relation between the consumption of Indian textiles in the eighteenth century and the onset of our own society.