The prints of Sebald Beham and his brother Barthel were the subject of a recent exhibition titled Gottlosen Maler at the Albrecht-Dűrer-Haus in Nuremberg (March 3–July 3, 2011), where this essay was included in the exhibition catalogue in German. Revised and expanded for publication in this journal in English, the essay addresses Beham’s biography and historiography and argues that Beham should be viewed as a highly creative and productive entrepreneur and as one of the first “painters” (to use terminology of the time) to specialize in prints. Between 1520 and 1550, he produced a prodigious number of prints.

Sebald Beham (1500–1550) was a highly creative artist who has recently begun to be appreciated for his contributions in the area of printmaking.1 Until the 1980s, many scholars valued Beham most as a “godless painter,” a term attached to him during his trial before the Nuremberg city council, a sensational event that takes center stage in many accounts of his career. In actuality, he was a prolific and important contributor to the expanding area of printed images (fig. 1).2 Beham is one of many understudied artists of the German Renaissance-Reformation period. Such artists as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, and Hans Baldung Grien have received far more scholarly attention, as indicated by the substantial bodies of published literature focused on their work. Beham belonged to the next generation after Dürer (b. 1471) and Baldung (b. ca.1484). His work stands somewhere between that of Dürer, his putative master, and Baldung, whose wild, excited horses reveal, in woodcut form, an artist grappling with demonic forces. Beham learned much from Dürer, including his graphic style of making lines, but his prints tended to push the social and publishing boundaries of the time more in the manner of Baldung.

Yet in contrast to both, Beham stressed prints far more than paintings, tipping the balance in ways rarely seen before, not only in the percentage of his work devoted to prints but also in the sheer number of prints he produced (Martin Schongauer was an even earlier exception–his prints greatly outnumber his known paintings).3 This essay explores Beham’s life and the ways in which he has been portrayed in published studies. It will suggest as well areas for future exploration that acknowledge Beham’s large contribution to both the burgeoning new medium of prints and to new subject areas.

Sebald Beham produced his prints, paintings, and drawings before the advent of the specialization and professionalization of the printmaking industry around the middle of the sixteenth century. In the years between 1530 and 1535, the names of designer, woodcutter or block cutter, and printer or publisher (if different from the block cutter or Formschneider) were only beginning to be recorded, if sporadically, on German woodcuts, and it was not until mid-century that Hieronymus Cock’s publishing house in Antwerp, The Four Winds, began to document the hands involved in the production of an engraving–designer, engraver, and publisher. Beham, who began his career in the 1520s and died in 1550, anticipated some of these developments–for example, putting his monogram on some of his prints–but he appears to have produced his large number of engravings on his own, without a printer other than himself. Beham’s print production as a whole, in engraving, etching, and woodcut, constitutes an early exploration of the genre of secular imagery. His scenes from everyday life anticipate trends in painting that would become a major emphasis in the seventeenth century.4

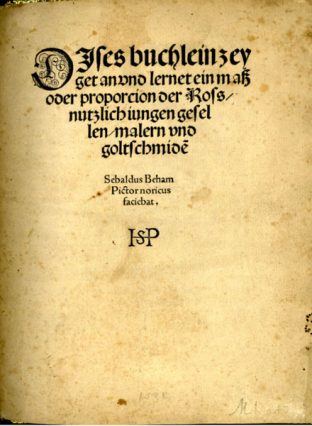

Before giving an account of his life, a note should be made about Beham’s name. Often (mistakenly) called Hans Sebald Beham in modern literature, the artist signed his work “Sebald Beham” (figs. 1, 2, 8), the name also used in contemporary documents connected with his activities.5 Sebald’s monogram may unwittingly have supported the modern misunderstanding of his name. Because the Franconian dialect of his hometown of Nuremberg pronounced a “b” as “p,” he used the monogram “HSP” until 1531. After moving to Frankfurt, he used “HSB.” The “H” appears to indicate the second syllable of his last name (Beham), in the manner of the “G” in the “AG” monogram of his contemporary Heinrich Aldegrever (1502–1561), who was active in Westphalia. It is also possible that Beham wanted to create a monogram that was clearly distinct from the “BB” of his brother Barthel.

Biography

According to many art historical accounts, the most decisive event of Sebald Beham’s life was the trial of 1525 before the Nuremberg town council, which will be discussed below.6 This episode was indeed crucial, but it was not all defining. The event does, however, raise the interesting issue of the scant survival of biographical information for Beham and his contemporaries. Scholars fixate on the trial because it is documented, unusually so for the time. But if this set of records had not survived, how would discussions of Sebald Beham, his brother Barthel, and their contemporary Georg Pencz, all accused of “godlessness,” be framed? The trial occurred at the halfway mark of Sebald’s life and functioned as a pivotal point in his career. Before the trial, he was active as a painter, engraver, and designer of woodcuts and stained glass, who had been trained in the Nuremberg tradition of Albrecht Dürer (fig. 3). During this time there are no records of any panel paintings in oil by Beham, although he was a prolific designer of stained-glass panels. Whether such glass panels were considered to be “painting” in Beham’s day cannot easily be answered, but it is clear that his activity designing Nuremberg stained glass increased beginning in 1522.

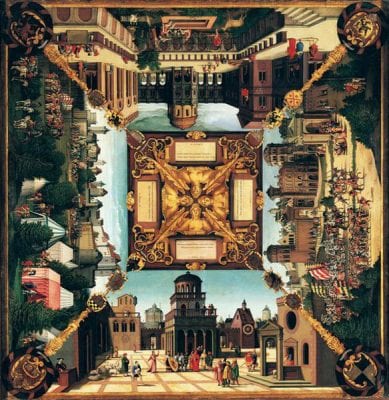

After the trial of January 26, 1525, Beham was exiled along with the other two defendants; they returned to Nuremberg nearly eleven months later on November 16. Beham appears to have left Nuremberg again soon thereafter (his brother Barthel did the same and settled in Munich), moving possibly to various towns in the region. In 1531, Sebald settled in or near Frankfurt, where he continued his successful career as a print designer and painted his one surviving panel, a painting for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, as well as numerous illustrations for a prayer book for this same patron (see figs. 1, 14). In this Frankfurt phase, which continued for some twenty years until his death, Beham appears to have perfected his graphic style in both woodcuts and engravings; he created some of his most interesting work during this period (fig. 4).

Beham was born in Nuremberg two years after Dürer had achieved international success with the publication of his Apocalypse in 1498. A landmark in the history of prints, this work undoubtedly increased the demand for Dürer’s superb printed works on paper and created an interest in the medium that helped the next generation of Nuremberg print designers (to which Beham belonged). No written documents exist to confirm that Beham was apprenticed to Dürer, although visual evidence, beginning with his early dated works, strongly points to such a connection. Lack of documentary evidence might suggest that Beham emulated Dürer’s style without ever having set foot in his shop. But it is important to keep in mind that much evidence from the period, both visual and textual, has been lost or was never recorded.

Because of the absence of guilds in Nuremberg, the crafts were overseen by the town council and the craft office (Rugsamts), with painters and engravers belonging to the so-called Freie Künst (craft organizations). Such organizations were regulated rather severely by the town council, down to such details as overseeing the sealing of letters. Those in the “free arts” had workshops employing apprentices and journeymen, who could become masters. Citizenship was usually required for admission to these organizations, as was marriage; foreigners and children were not accepted. In Nuremberg, a trial piece rather than a masterpiece was required and this was placed in the Rathaus in the room called the Regimentstube.7

The visual evidence linking Beham to Dürer begins in 1518 with a pen-and-ink drawing of various heads in Braunschweig.8 It shows Dürer’s influence in the use of curved lines to model forms, seen notably in the arcs of cheek and neck, an approach that is also evident in a small engraving of a young woman signed “HSP” and dated 1518.9 Around this time, Beham made a drawing in roundel form for a stained-glass panel showing an amorous peasant couple holding cheese and eggs, which exists today as a copy.10 The composition appears to have been based on a workshop drawing exercise for Dürer’s apprentices. Using such visual evidence, along with other clues, Beham’s apprenticeship to Dürer can be dated approximately to the years between 1515 and 1520.11 The few surviving documents indicate that in 1521 Beham was a Malergeselle (journeyman painter) and that by 1525 he was a painting master with his own shop in Nuremberg.12

Dürer taught his apprentices, who included Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Schäufelein, and probably Beham, the important skills required by the German Renaissance painter: grinding pigments and making various paints; preparing and smoothing wood panels and applying oil paint to them; making preparatory drawings for paintings and stained glass; designing and cutting engravings and etchings into copper and iron plates and printing them on a cylinder press; and designing and perhaps cutting woodcuts and printing them on a flatbed press. Beham would also have learned to make and use a variety of printing inks and to differentiate among the types and qualities of different handmade papers that were produced from linen rags in both local and distant paper mills. These may have included the mill run by the heirs of Ulman Stromer, who established the first paper mill in Germany at Nuremberg in 1390, which is shown in the Nuremberg Chronicle dated 1493.13 From Dürer Beham also undoubtedly acquired a sense of the print market–which print subjects were popular and suited the artist’s talents, as well as the sizes that worked best for particular subjects.

At the time of Beham’s apprenticeship, Dürer had just completed his master engravings of 1513 and 1514, including his Saint Jerome in His Study and Melencolia I, and he was still overseeing his enormous woodcut project The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I, which measured at least 357 x 295 cm when assembled from nearly two hundred woodcuts. Beham began designing large woodcuts approximately a decade later, another indication of Dürer’s early influence. Dürer had also produced a few etchings on iron during the 1510s that show the complexity and difficulties of the technique. Because the plates were made from iron, they rusted. Beham worked with etchings for a brief period a few years later (fig. 5), around 1520, and his plates also rusted and showed evidence of production problems: false biting is present in several impressions.14

Nuremberg records do not indicate whether Sebald worked together with his younger brother Barthel, although their prints do reveal a close relationship with regard to artistic approaches and styles (figs. 3 and 6). Both Behams made engravings early in their careers, yet each soon specialized in different but complementary areas. In addition to designing woodcuts, Sebald concentrated on designs for stained glass, while Barthel emphasized engravings and panel paintings, especially portraits. By working in diverse media, the brothers followed in the path of Dürer, who worked in the same variety of printing and painting techniques, in addition to pen-and-ink designs enhanced with watercolor. Until his trial in 1525, Beham is believed to have been a prominent, and perhaps the leading, designer of stained glass in the years right after the death in 1522 of glass designer Hans von Kulmbach.15

Color was still an important aspect of the aesthetics of the visual arts during Beham’s early years when designing stained glass belonged to the activities of a painter. Beham’s prints may have been colored more often than is generally acknowledged. A case in point is his Feast of Herod woodcut from ca. 1530–35. In the impression displayed for the Gottlosen Maler show at the Dürer-Haus (fig. 7), color was applied by hand over every area of the print. Such extensive use of color is often thought to have been unusual at a time when, it is believed, most prints were selectively colored, if at all.16 But another impression of the same work in Berlin’s print collection was also colored heavily throughout, resulting in two of the three known impressions giving the appearance of contemporary panel painting.17 In Beham’s time, such coloring may have meant the work was thought of as a “painting” or the work of a “painter.” Although the dividing line between prints and paintings is firmly drawn today, in the early sixteenth century, it may have been more fluid. Designing stained glass and hand-colored prints may have sufficed to earn the designation “painter,” especially if the artist was trained as a painter, even if paintings on panel were not central to his activities.

In 1525, Sebald and Barthel Beham were twenty-five and twenty-three-years-old respectively. Their training was typical for the time in Germany, apprenticing at roughly age fifteen and becoming a master and setting up shop at twenty-five. Similarly, Dürer was apprenticed to his goldsmith father until 1486, when he was fifteen, then with the painter Michael Wolgemut from 1486 to 1489. Dürer became a master at age twenty-three in 1494 after marrying Agnes Frey. In 1525, both Behams were young enough to be caught up in the excitement and turmoil of the changing religious and political scene in Reformation Nuremberg, where, since 1520, Martin Luther’s new ideas questioning the tenets of the Catholic Church had been making inroads in society.

In January 1525, two months before Nuremberg officially became Lutheran, both Sebald and Barthel Beham were brought before the town council, along with the painter Pencz, for their radical proclamations on religion and local politics. The Behams’ repudiation of the outward manifestations of the Christian religion, particularly the traditional Mass and the sacrament of baptism, has been directly linked to the spiritualism of Hans Denck, the schoolmaster of the church of St. Sebald and an acquaintance, perhaps friend, of Sebald’s.18 Denck, in turn, is believed to have been influenced by Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, who called for expanding communion to the laity by offering both wine and wafer.19 Beham appears to have become more closely acquainted with another radical reformer and spiritualist, Sebastian Franck, whose Chronicle of the Turks, printed in 1528, maintains that spiritualists desire an invisible church based on inner beliefs rather than an external church emphasizing show and ceremony. In the same year on March 17 Franck married one Ottilie Beham, probably Sebald’s sister, thereby becoming part of his family. Luther stated that Franck’s radical spirit had been blown into his ear by his wife, Ottilie.20

The timing of Beham’s trial, two months before Nuremberg adopted Lutheranism as its official religion, was unfortunate. Nuremberg was an imperial city directly responsible to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Deviations from Catholic orthodoxy were unwelcome and the new Lutheran ideas needed to be expressed carefully. The attitudes of Sebald and his brother were thus radical enough for Nuremberg’s town council to expel them from the city for most of that year.

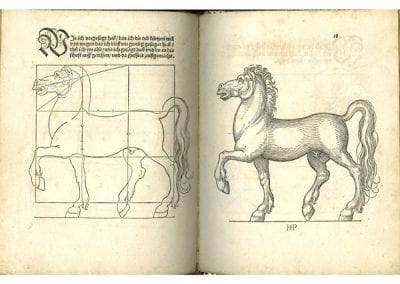

In the following years, Beham once again ran into trouble in Nuremberg. On July 22, 1528, the town council prohibited Beham and his colleague “Iheronimus formschneidern,” probably the printer-woodcutter Hieronymus Andreae, from publishing Beham’s book on the proportions of horses (figs. 8–9) until Dürer’s book on human proportions was published posthumously by his widow, who was the manager of Dürer’s workshop. The fact that Beham fled town quickly when summoned by the authorities (which resulted in his wife having to send his coat to him)21 might suggest that he was indeed guilty of plagiarism, as charged, although his guilt has been neither proved nor disproved. But it is also possible that Beham left posthaste because he feared he would be imprisoned or expelled, having previously experienced the power of the Nuremberg authorities to do just that. An impartial study of the historical situation, including unpublished sources in Nuremberg, might provide insights into Beham’s innocence or guilt, especially if it placed the case within the context of a time when copying visual works and texts was common practice.

Judging from the towns in which his book illustrations were published, it appears that Beham may have moved from place to place over the next few years, visiting or staying in Nuremberg during 1526, 1527, and 1530, in Ingolstadt in 1527, 1529, and 1530, and Augsburg in 1529 and 1530. In 1530, Beham was in Munich, probably with his brother Barthel, a resident there, for the entry of Emperor Charles V, an event for which he designed a large woodcut.22 Thus Ingolstadt, Augsburg, Munich, and Nuremberg are all possible locations where Beham might have been living between 1525 and 1531.23 However, because designs for book illustrations could be sent by courier and could thus have been designed off site, confirmation of his residency in these locations requires confirmation from other sources. A fresh study of Beham’s whereabouts during these years could confirm or refute such possible locations and determine whether Beham was still living in Nuremberg.

Why Beham left Nuremberg and settled in Frankfurt is a centrally important question that needs consideration from several perspectives. Nuremberg was a socially conservative town with a powerful town council dominated by the patriciate, which regulated life for its residents, including the personal and professional lives of artists like Beham. And Beham had experienced several conflicts with the council over time. Frankfurt, by comparison, may have been attractive to Beham for several reasons (all of which require research). He could start fresh there and leave his “godless painter” reputation behind; Frankfurt may have been less socially restrictive than Nuremberg; and it offered new possibilities in the area of printmaking. Specifically, a new book publishing industry appears to have just begun in Frankfurt for which Beham could design illustrations. In addition, very little engraving seems to have existed there before Beham’s arrival. Beham may have been invited to come work in Frankfurt by one or more of the town’s publishers. The likely candidate for having made this invitation is Christian Egenolff (1502–1555), one of the first book printers in Frankfurt, who would work with Beham repeatedly over the next two decades.24 Thus Beham appears to have moved into a town that lacked real competition in the areas where he would soon flourish: engraving and designing book illustrations.

A learned man, Egenolff was important for Beham’s later years in Frankfurt and possibly his early ones there as well. Younger than Beham by two years, he was one of the first book printers to move to Frankfurt, arriving there in 1530 and becoming a citizen in 1532. This more-or-less contemporary dating suggests that Beham and Egenolff were setting up shop and establishing themselves professionally in Frankfurt at the same time.25

Beham’s brother Barthel had moved to Munich shortly after his exile from Nuremberg in 1525, resulting in an additional possible reason why Nuremberg held less attraction for Sebald. During his years outside Nuremberg, between 1525 and 1531, he may have experienced first-hand the problems involved with moving from town to town in search of work and a place to settle. Beham may have witnessed such difficulties on the part of his brother-in-law Sebastian Franck and his friend Hans Denck (who died from the plague). Each was an exiled spiritualist traveling in search of a permanent residence in his last years.26

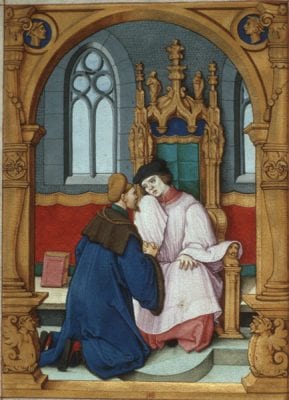

Beham’s move to the Frankfurt am Main area may have been facilitated as well by Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg. Beham’s painted projects for Cardinal Albrecht, archbishop of Mainz, which are securely dated 1531 (fig. 10) and 1534 (figs. 1, 14),27 may have provided just enough start-up security for him to make the move. Frankfurt was an imperial city under the spiritual jurisdiction of the cardinal and located near the cardinal’s residences at Mainz and Aschaffenburg, the latter just east of Frankfurt.28 It is possible that both Egenolff and Cardinal Albrecht made Beham’s move attractive by ensuring work for him, as suggested by events of 1538 and 1539, when Beham designed woodcut illustrations for two books published by Egenolff that Franck wrote in German. One final reason for Beham’s move appears to have been the Frankfurt book fair. In 1547 Beham was living at St. Leonard’s Gate on the Buchgasse in the doorkeeper’s residence next to the site of this great book fair.29 In short, the economic possibilities of working with at least one printer in Frankfurt and vending his works at the annual fair may well have been the main reasons for Beham’s settling and then staying in the city permanently, after some initial assistance from the cardinal.

Personal reasons may have also entered into Beham’s move, although known facts in this area are few. No information is known about his parents, nor whether Sebald was married and had children during his years in Nuremberg, although marriage was a requirement for his becoming a painting master in that city. In 1528, Beham may well have had a family with three daughters, for documents indicate that in March a painter named Sebald was ill and his three daughters were cared for in the foundlings’ house until he recovered. The painter in question may have been either Sebald Beham or Sebald Greiff, another painter about whom little is known.30 In 1540, Beham was indeed married to a woman named Anna, according to stone models for medals designed by Matthes Gebel, today in Berlin, on which both Sebald and Anna are shown in profile (fig. 11), he with short hair, she with hair covered by a net. Sebald’s age is given as forty, Anna’s as forty-five.31 After Anna’s death, Beham married again in 1549. This new wife was named Elizabeth; she was the daughter of Matthes Wolf from Büdingen, a shoemaker (Anna’s father was also a shoemaker).32

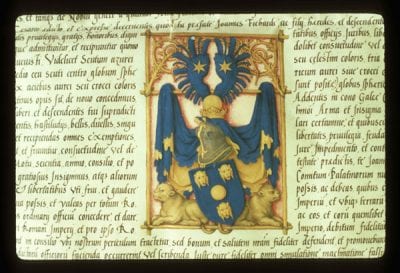

Lack of work does not appear to have been the cause for Beham’s move away from Nuremberg, even though at this time other painters, like Hans Holbein the Younger, were relocating great distances for work. Drawings by Beham point to his attracting ample patronage in Nuremberg from Catholics and Lutherans alike. Nor do Beham’s personal politics seem to have been an issue with his patrons, including Cardinal Albrecht, even though they had been for Nuremberg’s town council. In the early 1520s, before his exile, Beham designed stained glass for an imperial patron and for Elector Frederick the Wise, duke of Saxony.33 The elector was a protector of Luther (a professor at Frederick’s university), who gradually changed his own devotional practices. Beham also worked with various printers in Nuremberg (Albrecht Glockendon, Niklas Meldemann, and Hans Guldenmund) and woodcutters, including the highly skilled and renowned Hieronymus Andreae, notably in 1528 and between 1531 and 1535, and possibly earlier. In Frankfurt, Beham continued this mix of patrons during the last decade and a half of his life. During this time, he worked for new members of the nobility, including Johann Fichart and Justinian von Holzhausen for whom he painted patents of nobility or coats of arms, today in Frankfurt’s Stadtarchiv (fig. 12).

The large woodcuts Beham designed for Nuremberg printers may have helped him finance his move to Frankfurt. The designs Beham made for the Large Kermis woodcut dated 1535, for example, published by Albrecht Glockendon at Nuremberg, could have been delivered by courier from Frankfurt rather than in person, with the designs drawn on separate sheets of paper or directly onto the blocks.34 Alternately, Beham may have delivered some of the designs when he appeared in person to relinquish his citizenship on July 24, 1535 at Nuremberg’s town hall. After 1535, Beham stopped designing woodcuts for Nuremberg publishers but continued providing illustrations for books published by Egenolff. He also increasingly turned to making very small engravings in series at Frankfurt.

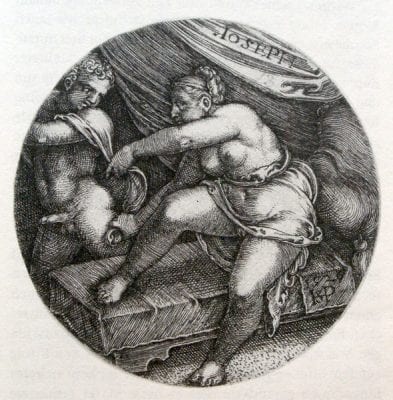

Beham’s move to Frankfurt may have offered him an opportunity to avoid the strictures of a town censor. In Nuremberg, this censor was required to review and approve printed works before their publication. Given the newness of its book publishing industry, it is unclear whether Frankfurt had a similar system of censorship in place or needed one. The existence of censorship in Nuremberg perhaps provides another reason for Beham’s move. It seems possible that his representation of sexuality and the human form were an issue for the censors. His small engraving Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife dated 1526 (fig. 13), only 5.3 cm in diameter, possibly made in Nuremberg, shows Joseph fleeing in an aroused state and Potiphar’s wife attempting to delay him, both with exposed genitals, unusual details for the time. An impression in the Albertina includes pink coloring added by hand to Joseph’s erection. Beham’s designs for a wallpaper depicting nymphs and satyrs also show an emphasis on sex. Two woodcuts datable to around 1520–25 offer a large-scale, wall-size rendering of phalluses and pudenda and point to an artist possibly interested in pushing the boundaries of acceptability.35 In Beham’s small engravings of peasant festivals made at Frankfurt during the late 1530s to late 1540s, he stresses adultery, groping couples, and vomiting and defecating peasants. Such emphasis on the body appears to have been unusual for an artist of the high caliber of Beham.

Although Beham’s most unusual images stress the body, his prints include a wide variety of traditional themes derived from the Bible, saints’ lives, and mythology. Other new themes include genre scenes showing everyday life and subjects that combine genre and religious subjects. Beham’s scenes of nudes, sex, and the body reveal an artist who was inventive in his own moment and willing to strike out in new directions. Such independence and inventiveness were requirements for success in an open print market that offered no steady income from patrons at a time when traditional religious imagery was increasingly questioned due to the Reformation. This open market encouraged artists to produce new imagery, including tiny engravings that appealed both to a small, selective audience of collectors of images and to a large audience for whom subjects from daily life like bathhouses and peasant festivals were deemed interesting enough to be hung or tacked on walls.

In Frankfurt, Sebald reused motifs from his own large woodcuts as well as specific engraved compositions from his brother Barthel and several of his own series of small engravings. Sebald reworked the latter just enough to make them marketable as new. Although his reuse of his brother Barthel’s plates has been viewed as pirating, thus confirming Sebald’s reputation as the godless bad boy of the German print world, he probably inherited Barthel’s plates and workshop upon the latter’s death in 1540. It was customary at the time to pass the woodblocks used for printing woodcuts from one printer or publisher to another and to pass intaglio plates among family members.36

The rather large distance involved in Beham’s move from Nuremberg to Frankfurt, 228 km (142 miles), was not unique for the time. Dürer traveled over the Alps to Venice and down the Rhine to sell his prints. Lucas Cranach moved from Vienna to Wittenberg, and Hans Holbein the Younger relocated the farthest, from Basel to London. Like these artists, Beham proved himself to be a mobile, adaptable artist who exploited the relatively new interest in prints and then popularized the subject of scenes from everyday life for audiences in Germany and throughout Europe.37

Although “printmaking” had not yet become a term used in Beham’s time, his specialization in prints shows that he was a transitional figure between earlier painter-engravers like Schongauer and etchers like Daniel Hopfer, who increasingly emphasized prints while leaving painting behind. For just as Beham had turned away from his large woodcuts toward small engravings, Christopher Plantin in Antwerp turned to intaglio plates, both engravings and etchings, for the book illustrations he made beginning in the mid-1550s.38 Seen within this larger historical context, Beham’s contributions to printmaking indicate he was a pivotal figure in the move toward prints as a viable area of professional specialization.

Historiography

Beham has long been overshadowed by his older contemporary Albrecht Dürer, resulting in a picture of him in the literature as a less talented imitator of the master. However, publications from the last few decades offer a new and much more positive image of Beham.

Research on German art of the first half of the sixteenth century has focused on Dürer, Hans Baldung Grien, and Hans von Kulmbach, a younger painter from Nuremberg, who trained in Dürer’s workshop and died in 1522.39 Even Beham’s younger brother Barthel has been the subject of a recent monograph by Kurt Löcher.40 All of these artists were more deeply centered in painting, the medium art history has favored. By contrast, most of Sebald Beham’s painted works were made in other forms: as designs for stained glass and book illustration, usually on paper but occasionally on vellum, and individual coats of arms for new members of the nobility (fig. 12). Only one of his panel paintings has survived, a tabletop dated 1534 now in the Louvre (fig. 14).41

Beham’s print production was vast. His engravings, etchings, and woodcuts number over 1,500 existing works. Each print has survived in as many as a half or a full dozen impressions located in museums and collections across Europe, the U.S., and beyond. That Beham’s oeuvre as a whole has not been studied in an overarching monograph may be explained first by his preferred medium of prints, and second by his enormous output. A single study would constitute an overwhelming task. Beham’s drawings, too, have never been studied as a group. Often preparatory to his designs for stained glass in Nuremberg and possibly in Frankfurt, they are–with a few exceptions–all that survives of his output in the fragile medium of glass, which is prone to suffering from the vicissitudes of time and the ravages of war.42 Given that a single publication addressing all Beham’s prints, painted works, and drawings would be of tremendous size, it is no wonder that a comprehensive monograph has not yet been written.

Another possible reason why Beham has not been studied more thoroughly is that no single work by Beham stands out as his masterpiece. There is nothing comparable to Dürer’s Melencolia I, Schongauer’s Temptation of Saint Anthony, or Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Furthermore, prints have been considered over the centuries less important than paintings in part because the materials involved, paper and ink, were less expensive than the wood and oil paint necessary for a panel painting. Because prints were cheaper to purchase than other art forms, and remained so into the twentieth century, the modern perspective has deemed them less fine and less worthy of study than paintings and sculpture of the early modern period.

Publications on Beham began in 1875 with Adolf Rosenberg’s book addressing the works of both Sebald and his brother Barthel as Renaissance painters, reflecting the traditional art historical preference for painting.43 Rosenberg treated Beham’s life and work chronologically; especially noteworthy is his assertion that Beham left Nuremberg and established himself in Frankfurt in 1534, rather than a few years earlier. This contradicts the date 1531 on the prayer book for Cardinal Albrecht, which bears Beham’s Frankfurt monogram (see fig. 10). Also of interest is Rosenberg’s helpful appendix of Sebald’s works, the earliest comprehensive attempt at compiling a list of his paintings, drawings, engravings, and woodcuts. Rosenberg also listed engravings for Barthel but no woodcuts. (Attributions to Barthel for woodcut designs have subsequently see-sawed in the literature between the two Behams, but such attributions to Barthel remain unconvincing.)44 One of Rosenberg’s entries is particularly worth highlighting. Sebald’s book on the proportion of horses was published at Nuremberg in 1528 without the name of the publisher, Hieronymus Andreae (figs. 8–9). At a time when books and pamphlets published in the city were legally required to carry them (although they were not always included), the omission of the publisher’s name must have been intentional to protect the publisher’s identity, since Beham had been forbidden to publish the work by the city council.45

In an article from 1897 on the subject of Beham’s move to Frankfurt, Alfred Bauch made the case that this move took place in 1535, basing his assertion on the irregularity of Beham’s use of his old and new monograms during the early 1530s.46 But Bauch cited no specific examples to support his ideas nor have such irregularities in Beham’s works been discovered by the present author. Although Rosenberg and Bauch made the case for Beham’s move to Frankfurt in the mid-1530s, neither author’s argument is convincing in light of the inclusion of Beham’s Frankfurt monogram “HSB” on the prayer book illustrations dated 1531 mentioned above.47

The next important work on Sebald Beham was Gustav Pauli’s monumental and impressive catalogue of prints published in 1901 (fig. 15), with an addendum in 1911; both were reprinted in 1974.48 Pauli’s work remains the gold standard for organizing Beham’s prints both in print collections and in such standard print catalogues as the Hollstein series on early modern prints.49 Pauli explored each printed image by Beham, providing dimensions and locations of the known impressions and the visible artistic influences. Written to supplement Pauli, Heinrich Röttinger’s book on Beham, published in 1927, pales by comparison because of the uneven rigor of its scholarship and quality of argument.50 Pauli’s work continues to be a tour de force of print scholarship, produced at a time before reproductions were commonplace, and is an indispensable resource for the study of any printed work by Beham.

By and large, the literature on Beham has viewed the artist and his work from distinct, fragmentary perspectives, in tandem with changing methodological approaches in art history. Pauli’s early-twentieth-century book parallels the endeavor to catalogue works of art in museum collections by artist, a system for sorting and organizing that was characteristic of the discipline of art history in its early years. The next major publication on the artist, Herbert Zschelletschky’s Die drei gottlosen Maler von Nürnberg, was written over fifty years later, in 1975, when Germany was divided.51 Zschelletschky’s views on Beham as a politicized, radical artist should be understood within the context of East German politics. His argument aligned the issues of the Peasants’ War and Lutheran conflicts with Beham’s unorthodox ideas, as articulated during the trial of 1525. Thirteen years later the approach to Beham changed yet again in a exhibition catalog edited by Stephen Goddard.52 This more ideologically balanced work addressed the engraved prints of Sebald and Barthel within the context of the Little Masters circle, a group of Nuremberg and German engravers from the generation following Dürer whose name derived from their prints’ small size. Goddard’s catalogue, which includes excellent biographical notes on the artists, and the volume of essays that resulted from the exhibition symposium are important contributions to a more balanced study of prints by both Behams.53

As art history began to emphasize theoretical approaches for interpreting visual works over an artist’s biography, Keith Moxey countered Zschelletschky’s political interpretation in an article from 1982. Moxey argued that at the time Beham made his prints, social and market forces would have encouraged artists to produce subjects that sold well.54 Moxey asserted that it was historically implausible that Beham’s political views could have influenced the contents of his prints; instead Beham’s work mirrored contemporary attitudes that derided peasant festivals. Moxey’s article received great acclaim for its clearly articulated theoretical approach and critical interpretation of the peasant festivals.

In publications dating from 1983 to 2008, I interpreted those same peasant festival woodcuts by Beham as conveying diverse meanings, including positive ones.55 This approach paralleled, albeit unconsciously on my part, the rise of multivalent interpretations in art history. The woodcuts themselves were studied in tandem with a variety of contemporary sources, including town council documents, popular and elite literature, historical and religious events, folk customs, and the work of various contemporary artists. This broader set of sources resulted in an acknowledgment of the multiple ways Beham’s work could be interpreted and the various aspects of contemporary culture that underlay his creative subject matter.

Positive understandings of Beham and his work reach back to the beginning of Beham scholarship with Rosenberg. Pauli documented Beham’s rich sources and viewed him as an epigone of Dürer. Christian von Heusinger took a similar position in his important publication of 1976 on large-scale woodcuts, Riesenholzschnitte.56 In 2007, Jürgen Müller offered a different approach in his discussion of Beham’s Fountain of Youth woodcut from 1531.57 In a highly original understanding of Beham’s print, Müller interpreted it as an indication of Northern European anxiety and suspicion of Italy as the cultural center of the European West. Müller continued this approach to Beham and Dürer in Die gottlosen Maler von Nürnberg exhibition he organized in 2011, in its accompanying catalogue, and in a recent article on Dürer’s peasants for the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art.58 In Before Bruegel in 2008, I presented the view of Beham as a creative entrepreneur and inventor of peasant festival imagery, an artist who reused and rethought his own prints, while developing an ever-expanding market for them. I explored various peasant festival subjects, first the woodcuts, then engravings, from a representation of a spinning bee to the various kermis woodcuts Beham designed.

In 2010, Mitchell Merback addressed the meaning of Beham’s engraving titled Impossible of 1549 within the context of the artist’s thinking during his later years.59 Merback stressed paradox, Christian freedom, self-knowledge, and the conflict of living in an era of reform as seen through this engraving, which shows a man attempting to pull a tree out of the ground. In a book from 2010 edited by Karl Möseneder, various authors–primarily advanced graduate students at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg–argued that several small print series engraved by Beham and the Nuremberg Little Masters spread new imagery to both princely courts and the middle class. The authors emphasized that the engraved series were intended for contemporary collectors, served as models for objects made by artist-craftsmen, gave rise to a new formal language, and originated from the meeting of artists in the circles of Dürer and Raphael.60

The exhibition catalogue Die gottlosen Maler von Nürnberg of 2011 mentioned above (fig. 16), edited by Jürgen Müller and Thomas Schauerte, focused on the Beham brothers’ prints. Essays on Sebald Beham and Hans Denck (by this author and Michael Baylor) addressed two important individuals in the circle of the artists known as the godless painters. Other essays addressed the questions of how godless the “godless painters” were (Gerd Schwerhoff) and transcribed the documents from the trial of the Beham brothers and Georg Pencz (the exhibition displayed the documents translated into contemporary German). Yet, other essays included the topics of patriotism (Jessica Buskirk), the fool and the scatology-vulgarity of the time (Birgit Ulrike Münch), the peasant (Jürgen Müller), peasant festivals (Bertram Kaschek and Wolf Seiter), the fountain of youth (Jan-David Mentzel), and Christian Egenolff, who completed Beham’s Kunst- und Lehrbüchlein book of 1552 (Sabine Peinelt). The leitmotif of organizer Müller, running throughout the introductory essay, was that of the “subversive picture” (das subversive Bild). Behams’ prints, he asserted, have the same skeptical and daring, even cheeky, spirit (frechen Geist) that appears in the two brother-artists’ testimony during the Nuremberg trial.61

All of this scholarship has done much to enhance and expand our understanding of Sebald Beham, recognizing his many talents in inventing and marketing new subjects and seeing in his staggeringly large number of prints compelling evidence of his role as a print entrepreneur. In 1547, three years before Beham’s death, Johannes Neudörfer acknowledged Beham’s importance as a printmaker when he stated that both Sebald and Barthel Beham were very famous and that their entire print oeuvres, as well as individual prints, were available in good supply. Three years later, the Frankfurt city council awarded twelve talers to Beham for a triumphal arch he had presented to the city as a New Year’s gift; the previous year they had given him the same amount for an also now-lost panel painting with an inscription in verse.62 How ironic, given his youthful difficulties with the Nuremberg authorities, that in the last year of his life Beham should be so honored by his adoptive hometown. Whether Beham had changed in his later years or whether it was Nuremberg’s more conservative climate that had posed the problem from the beginning are questions that await further study.