The Courtauld Gallery has three works by Peter Paul Rubens depicting the Conversion of Saint Paul, all dated to ca. 1610–1612: a compositional drawing, an oil sketch, and a finished painting. The serendipitous survival of these works provides insight into Rubens’s creative process and has long been a topic of discussion for art historians. Recent technical study and improved imaging techniques have highlighted Rubens’s extremely fluid approach to the development of the design and revealed complex reworkings of all three compositions. These findings suggest a much longer gestation of these ideas than the 1610–1612 date proposed, and they cast light on Rubens’s broader working practice and his ceaseless striving for aesthetic perfection, combined with a pragmatic approach to the reuse and reworking of his compositions. Building on research done by E. Melanie Gifford, the complex changes revealed by X-ray; by infrared, transmitted, and raking light; and by microscopic examination can be explored using enhanced image tools and navigation. Readers can compare works of art with each other and with their technical images using the “IIIF multi-mode viewer” to better understand Rubens’s artistic exploration of ideas and aid their own research.

Introduction

Rubens’s artistic practice employs a variety of drawings, painted studies and compositional sketches in order to devise the final work, and the immediacy of Rubens’s preparatory works has long encouraged art historians to use them as a window into the artist’s creative process. The Courtauld is fortunate to own three related works—preparatory drawing, large sketch and finished painting (figs. 1, 2, and 3)—all purchased separately by the scholar and collector Count Antoine Seilern (1901–1978). An astute connoisseur, Seilern had a special interest in Rubens’s working method, and the gathering of these works offers a particular insight into this process. Similarly, technical study permits us to see further into the intermediary stages of the painting’s creation, giving additional tantalizing glimpses into the development of its composition. By overlaying images created using infrared reflectography or x-radiography with those taken using different light sources, such as transmitted light or raking light, we can glean new insights. Using the possibilities afforded by new technologies, we are now able to share these images at high resolution (fig. 56) and carefully registered with one another, allowing us to peer virtually into Rubens’s studio, or perhaps over his shoulder at the easel, to see the step-by-step progression of his ideas.1

Rubens painted the subject of the Conversion of Saint Paul several times during his career; his first attempt, dated to ca. 1599–1601, is in the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein (fig. 4).2 A later version, formerly in Berlin, is now destroyed but known via print and painted copies as well as its oil sketch in the Ashmolean, dated to ca. 1621 (fig. 5). The Courtauld group represents an intermediate version and traditionally has been dated to 1610–1616. In all three versions, Rubens shows the saint after his Damascene conversion, having fallen, blinded by heavenly light, to the ground. Both the Liechtenstein and Berlin compositions show Paul falling forward over the neck of his horse, while the Courtauld compositions show a different solution, with Paul falling backward. In the Liechtenstein and Courtauld paintings Paul is shown with a sword and helmet to indicate his status as a soldier persecuting Christians, while the Berlin painting replaces these with a breastplate. The location of the miraculous event, on the road to Damascus from Jerusalem, is indicated by the presence of turbaned figures and, in the earliest version of the subject, a camel train. Over the course of his career Rubens reduced the cast of figures from a crowd, in the earliest version, to a few figures struggling to control their frightened horses around the body of the prostrate saint, in the final compositional idea. He reduces the didactic detail, increasing the emotional power and emphasizing the figure of Paul. The artist’s journey to this final treatment is by no means straightforward, and close study of the Courtauld works demonstrates his constant experimentation and exploration of pictorial ideas, something paralleled in E. Melanie Gifford’s recent study of The Fall of Phaeton.3

In the Courtauld series of works depicting the Conversion of Saint Paul, we can see Rubens making major revisions to his sketches, both drawn and painted, which might be expected. Most important, however, we see the large-scale reworking of the finished painting. This reworking, and its relationship to the preparatory sketches, allows us to explore more fully the creative process of the artist and hypothesize over the motivations for this change. The final painting of The Conversion of Saint Paul appears to have enjoyed a long period of gestation in the studio, with multiple revisions, including carpentry additions to the panel—a practice more often associated with Rubens’s personal, late landscape paintings. Cumulatively, these changes point to the Courtauld works being a much more complete bridge in Rubens’s evolution of the scene, from the Liechtenstein version to the lost Berlin painting, probably over a much longer period than has previously been considered. This study adds to a growing body of evidence that, at this point in his career, Rubens worked not in a straightforward, linear way—developing his design in drawings and subsequently fixing the composition in an oil sketch before tackling his final painting—but through an interactive back-and-forth, constantly revisiting motifs and reworking ideas in all formats, regardless of the level of finish expected. As Gifford’s detailed study of The Fall of Phaeton has emphasized, this seems to be a product of the artist’s personal evolution during a period when he was absorbing the many lessons learned from his European travels.4

Exploration of the changes to the drawing and the oil sketch also aids our understanding of how these preparatory works functioned within Rubens’s studio practice. Julius Held described this oil sketch as an “unusually tentative bozzetto,” recognizing the lack of finish and legibility in the composition.5 This type of oil sketch has been considered to be of a more personal, exploratory character within the artist’s oeuvre, distinct from the more didactic works (often described in Rubens literature as modelli) that were prepared to communicate designs to both patrons and workshop assistants, and which could also later serve as a record of finished designs.6 These two types of sketches are often distinguished by their level of finish and the extent of their compositional differences with the final painted work. Our discoveries, relating to the appearance of the Courtauld oil sketch as well as to its relationship with the final painting, prompt the question of how well the work fits into either category and, indeed, the wider reconsideration of whether such distinctions are actually helpful to our understanding of the complexities of the artist’s practice. In addition, comparing the oil sketch and drawing for the Conversion raises evidence that these different forms of preparatory works were retained within Rubens’s studio, which is of particular relevance to subjects that he returned to repeatedly over his career. Such works could be altered, reworked, or repainted at any point, rather than presenting a snapshot in time of his thoughts.

The exact dating and chronology of the Courtauld Saint Paul series has long been discussed, and, although these works have not previously been subjected to a full technical study, partial x-radiography on the final painting was undertaken and published by Count Seilern as early as 1955.7 Referring to the many pentimenti visible in the X-ray that relate to the drawn version of the composition, he proposed a sequence of “oil sketch, drawing and final painting,” all completed in a short space of time around 1615.8 Held subsequently acknowledged that Seilern’s chronology of the works could be correct, although a sequence of “drawing, oil sketch and final painting,” more typical of Rubens’s practice, was equally plausible.9 In his discussion of Rubens’s oil sketches, Held noted that complex surfaces of both the sketch and the painting show evidence of reworking and suggested that x-radiography might be similarly pertinent to the oil sketch.10 Dating the group to 1610–1612, Held suggested that parts of the final painting could have been reworked much later, perhaps around 1620.11 Finally, in his discussion of the group for the Corpus Rubenianum, David Freedberg argued that the oil sketch could be a quickly painted intermediary stage between drawing and painting and may even have been produced during the evolution of the composition of the final painted work.12 Freedberg dated the preparatory works and majority of the painting to 1610–1612 and agreed that Held’s dating of the further reworking was plausible. All three scholars discussed the link between the final painting and its possible pendant, The Defeat of Sennacherib, which share the same provenance until the Saint Paul painting was deaccessioned from the Alte Pinakotek in Munich in the early twentieth century (fig. 6). Our study aims to clarify the chronology of the works once and for all in order to better understand how the artist’s reworkings might be dated.

Finally, our findings on the Courtauld Conversion of Saint Paul group shed light on the commercial practices of the artist. While the existence of both a compositional drawing and a painted oil sketch might point to a commission,13 our hypothesis is that the painting was developed over many years in the studio, suggesting that it was in fact made for the art market. In particular, we propose that, having languished unsold, the painting (fig. 7) was revised to form a pendant to The Defeat of Sennacherib, a sales technique that may have a precedent in the written negotiations between Rubens and the British ambassador Dudley Carleton.14 Indeed, the complex development of the composition indicates that the creative function of the drawing and oil sketch, rather than their contractual use, was paramount.

The Oil Sketch

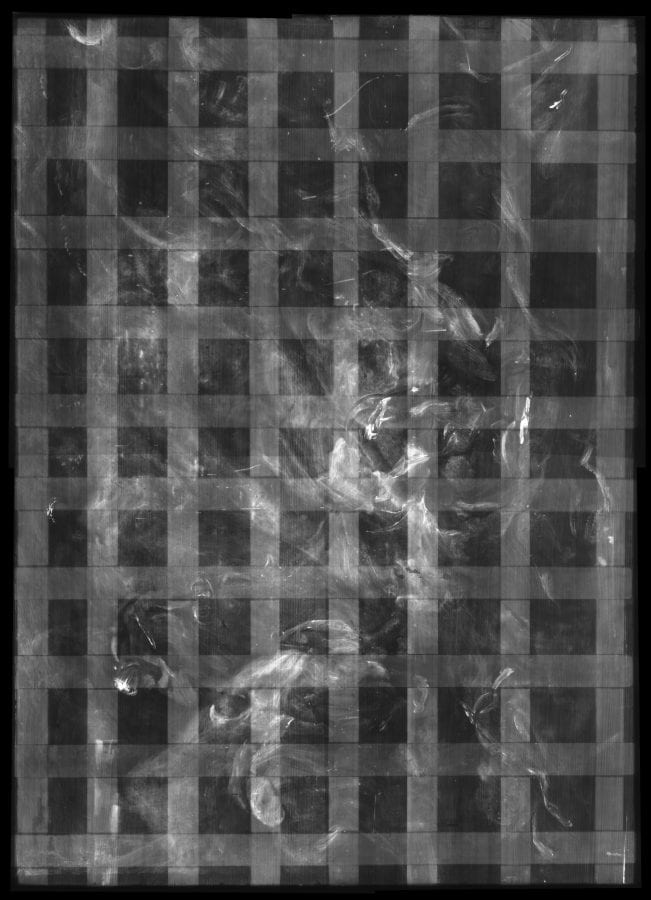

The oil sketch reduces the number of figures from the large cast of the Liechtenstein version and pushes them out to the corners of the panel so that there is little room for the sky or background landscape (fig. 8). The stricken saint falls from his horse into the picture plane, his prone figure lying stretched along the bottom edge. As Held noted, raking-light examination of the surface shows textural differences, which usually indicate major changes in the composition. Recent x-radiography (fig. 9a) and infrared reflectography (fig. 9b) of the sketch, however, has revealed that this is not the case: the sketch is painted thinly, with no changes, over the top of an unfinished painting of a large-scale seated female nude. The first composition was painted in a portrait orientation, and the head of the female figure lies beneath what is now the top right of the painted sketch for The Conversion of Saint Paul. The legibility of the upper image is compromised by the barely concealed composition beneath, which has become increasingly visible with age as the overlying oil paint becomes more transparent. It is clear that the upper paint layer, rather than having been extensively revised and reworked, is more spontaneous, capturing a single compositional idea, and that the image below is entirely unrelated.

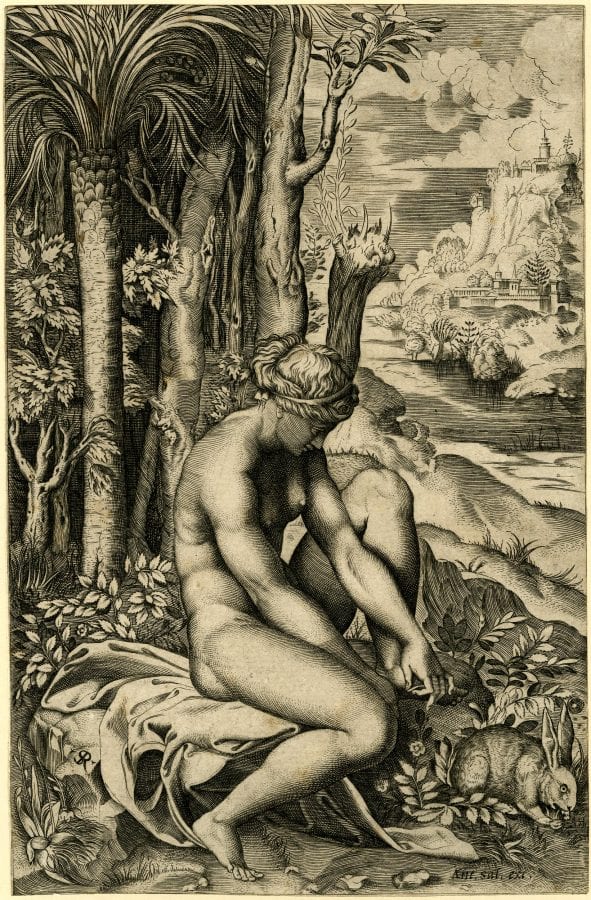

Using infrared reflectography, the underlying composition can be seen to depict a woman with her hair fastened up in a braid around her head, looking downward. She is seated with one raised knee, both hands in her lap or holding one foot, while the other leg is seen in side view, bent at the knee, beneath her. Her pose is copied from an engraving after Raphael’s Venus Wounded by a Thorn made by Marcantonio Raimondi’s assistant, Marco Dente da Ravenna (1493–1527), from Raphael workshop drawings (fig. 10).15 Rubens is known to have made painted copies after Italian engravings, with the early Adam and Eve (Rubenshuis, 1597–1600) and The Judgement of Paris (fig. 11) similarly based on Raimondi engravings after Raphael.16 Rubens’s lifelong practice sees him borrowing motifs from Renaissance masters; however, this close copying of complete compositions seems to be confined to the period during which he worked as a student of Otto Van Veen, in the last years of the sixteenth century.

The pose of the Venus figure is not repeated in any known painted work by Rubens, although it must surely be connected to his subsequent interest in both the antique Spinario and Crouching Venus sculptures (fig. 12). He saw the sculptures during his time in Italy and recorded them in his pocketbook, later adapting their poses for his early painting Susanna and the Elders (about 1606) in the Galleria Borghese (fig. 13).17 Indeed, his 1608–1610 painting Venus Wounded by a Thorn (USC Fisher Museum of Art, Los Angeles) arrives at a far more dynamic solution for the pose of Venus, which has been connected to sculptural, rather than engraved, prototypes.18

If the painting of the female nude belongs to this early period, the panel may have traveled with Rubens to Italy. There is some evidence that Rubens traveled with other unfinished paintings on panel: another early oil sketch, after Michelangelo’s Leda and the Swan, is painted on a reused panel. Underneath the Leda composition is a painted oval that has been linked to portraits of emperors painted by Rubens before 1600.19 These instances of reuse would seem to be driven by the limited availability of oak panels while traveling, or thrift on the part of the young artist who had perhaps no further use for the initial design. Paintings also traveled back with Rubens in the opposite direction; Gifford has argued that The Fall of Phaeton traveled back from Italy to Antwerp with Rubens, while the oil sketch that relates to both the Fermo and Antwerp paintings of the Adoration of the Shepherds could have traveled back from Italy to provide a source for the later Antwerp painting.20 Alternatively, the Courtauld Saint Paul panel may also have been among the paintings left behind in Antwerp in Rubens’s mother’s house and subsequently mentioned in her 1606 will.21 Rejecting Raphael’s Venus in favor of studies of classical sculpture made on his travels, Rubens may have decided to reuse the panel immediately on his return to Antwerp. In this context, it is relevant to note that among the oil sketches produced by Rubens for Samson and Delilah, a commission for Nicholas Rockox, is another reused panel, now known as The Capture of Samson. This panel, now in the collection of The Art Institute of Chicago, was turned upside down and reused, with Rubens painting over an initial design for The Adoration of the Magi (see fig. 27). The Adoration of the Magi was commissioned in 1609, and The Capture of Samson is dated to the same or the following year.22

Unfortunately, technical evidence cannot conclusively point to when the Courtauld panel was reused for the sketch of the Conversion of Saint Paul composition, whether in Italy or Antwerp. However, a high-quality green, celadonite earth has been detected in the center landscape, a pigment that is more usually found in Italian paintings and less commonly in Rubens’s palette. Rubens tended to use locally available materials, something commented on by Gifford in her observations on the priming and pigments employed in The Fall of Phaeton, and it is interesting to note that this green earth is known to come from Monte Baldo, near Verona.23 This might seem to link the oil sketch to the artist’s sojourn in Italy, whether he used the pigment while he was abroad or brought it back with him on his return to Antwerp. The Saint Paul composition is painted directly on top of the seated nude in what appears to be a single, rapidly painted layer, with no attempt at repriming, and no pentimenti to the uppermost composition could be detected in the complex X-ray and IRR. This seems to indicate the quick setting down of an idea rather than a more planned compositional sketch (fig. 14).

Consideration of Rubens’s early oil sketches suggests that they could have been made to explore compositional ideas, rather than—in the more usual way of his later practice—to present a composition for a specific final painting. Certainly, the sketch for Saint Paul is painted extremely loosely and rapidly and would have been of little didactic usefulness for a patron or studio assistant in beginning the final painting. The sketch diverges from all other versions of the composition in that it shows Paul’s horse in more dynamic motion, running away and not yet caught by the groom. While Paul’s pose was initially used for the subsequent final painting, the fleeing horse seems to have been entirely discarded, with all future versions of the subject showing Paul’s horse standing still in an otherwise tumultuous melee. Recent discussion of the group of preparatory works connected with the Samson and Delilah theme similarly acknowledges that, there too, Rubens appears to be working in the oil sketch form at an earlier stage in his creative process than might be expected, while still working out compositional ideas.24 This may also be connected with the decision to reuse panels previously painted with other compositions. Thus, oil sketches seem to have had a more fleeting purpose and have been more readily disposable at this moment in the artist’s development.

The Drawing

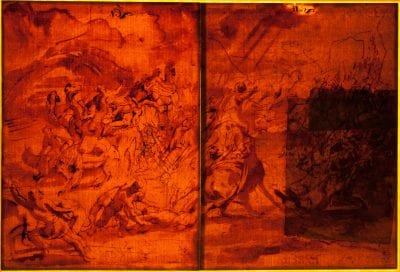

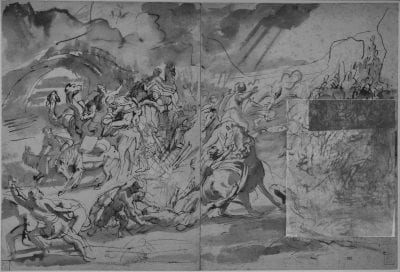

Though hasty, schematic, and sometimes hard to interpret, the drawing for the Saint Paul subject, unlike the oil sketch, represents a more fully developed composition, with a number of revisions (fig. 15). It depicts a denser, more drawn-out crowd and includes more of the landscape and sky, with an indication of rays of heavenly light and, at the left, the addition of a simple bridge like the one depicted in the early Battle of the Amazons (private collection, 1603–1605). Although the painting and the drawing do not now share the same compositional design, the X-ray study undertaken for Seilern in the 1950s by Stephen Rees-Jones at The Courtauld revealed that they were initially much more similar. Like the painting, the drawing has also been revised, with figures erased and pieces of paper pasted over sections of the composition. Technical study has allowed us to explore the first conception of the drawing in order to assess how it compares to the earliest version of the large-scale painted composition.

The drawing is made with iron gall ink on two sheets of laid paper, each now lined onto further sheets of laid paper and joined at the center seam. The drawing is recorded as two separate sheets from the seventeenth century onward, and the two pages were separated for over a century before being reunited in the Seilern collection. The drawing has long been recognized as being from two opposite pages of a sketchbook, and our study confirms this: transmitted infrared reflectography reveals that the two papers are of a similar type, with similarly spaced chain lines, but were not once a single sheet, since a watermark can be seen bisected by the central cut on the right-hand sheet (fig. 16). This watermark shows a motif within a circle, centered on the chain line, reminiscent of those commonly used on Italian papers of the period but not thus far recorded on any other papers used by Rubens.25

Before the sheets were rejoined at the center seam in the Seilern collection, each of the sides appears to have been lined at an early date. This explains why a loosely drawn rendering of a camel and two riders or fleeing figures on the reverse of the top right of the sheet has not been noted by previous writers, although it can now be seen using transmitted light (figs. 17 and 17a). This second quick sketch further differentiates this sheet from Rubens’s final painted depiction of the scene, which eliminates the camels in favor of horses.

This drawing on the reverse is further evidence that the sheets came from a sketchbook, and their dimensions suggest that the sketchbook may have been prepared from a number of recute or “crown”-sized papers bound in quarto.26 Subsequently, the drawing was cut from the sketchbook, and all but two of the sewing holes were trimmed away at the center.27 The drawing may have been one of several larger compositions cut in this way that found their way into the seventeenth-century collection of Canon Jan Philip Happart of the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp.28

While a number of Rubens’s drawings have been grouped together as belonging in bound sketchbooks, very few show evidence of having been drawn in a bound volume and could instead have been bound together by Rubens as a means of preserving important visual ideas.29 It is perhaps important to note that the 1612–1614 Bayonne drawing of the Death of Hippolytus is also composed of two sheets and is of almost the exact dimensions as the Saint Paul drawing.30 As Gifford explains, Rubens is likely to have been working concurrently on the Death of Hippolytus theme while developing the composition of Saint Paul.31

As is readily apparent in the transmitted-light image of the Courtauld Saint Paul drawing, additional sheets of paper, perhaps of a slightly lighter weight, were pasted on to facilitate changes to the design. The two additions appear on the right-hand sheet and include a larger square piece and a smaller rectangular piece. The smaller piece overlaps the square piece at the top (see fig. 17). These pieces both have deckle edges32—an artifact of the manual papermaking process—partially present, suggesting they may have been offcuts from other trimmed sheets. At the edge of these added papers, on the left-hand side, the protruding leg of an underlying figure has been erased using white bodycolor, which has now become quite thin and transparent (fig. 18a). Bodycolor erasing has been similarly used on the left-hand sheet: the group around the camel train originally included a figure leaping onto one of the camels (fig. 18b), and the group surrounding the saint featured a figure seen in profile, bent over with his left arm lowered toward the saint (fig. 18c). The figure appears to have been wearing a helmet, comparable to the armored man in the final painting. It seems likely that these changes were all made at the same time, rather than in two separate campaigns. These interventions demonstrate both the value of these drawings to the artist and his constant development of his designs at all stages of the artistic process.

Using image processing to compare the reflected- and transmitted-light images, it is now possible to visualize Rubens’s initial drawn conception of the scene (fig. 19).33 Surprisingly, this first design has rather more in common with the final painting of the Courtauld series than the drawing as it now appears. Beneath the paper additions are the bucking rear legs of a horse moving into the picture plane at the far right. In addition, a series of vertical hatchings suggest the outstretched neck and mane of another horse moving out of the picture plane. This horse has at least one rider, whose disembodied lower leg and foot is covered over with bodycolor at the left edge of the paper correction (see fig. 18a). A possible figure being trampled beneath can just be made out at the right-hand side. While the bucking horse seen from the rear appears in the Liechtenstein version of the composition, these “dueling” horses can be compared to the artist’s earlier drawing The Battle of the Greeks and Amazons, dated to ca. 1602 (fig. 20). They reappear, separated to either side of the composition, in the final painted version of the subject.

The changes to the drawing could have been made as part of the initial design process but, equally, could date to sometime later—certainly the compositional solutions do not seem to have been adopted in the painting (fig. 21). If, as it seems, the drawing came from a sketchbook of compositional designs, it may have been referred to and altered over the course of Rubens’s career. Certainly, the drawing provides clear evidence of Rubens’s iterative method of ceaselessly developing visual ideas to express favorite subjects.

The Painting

The painting, like the drawing, shows Rubens revising and refining the composition. The sky is further expanded and the vision of Christ is introduced, while the figure group is reduced and the attendants around the fallen saint are brought to the foreground. However, as in the drawing, substantial revisions were made to the composition of the final painting. Seilern recognized these thanks to the partial X-ray studies made at The Courtauld in the 1950s, which also acted to confirm the good condition of the paint layers generally.34 Infrared reflectography and new x-radiography of the entire painted surface have been undertaken for this study, alongside careful microscopic examination. Dendrochronology determined a precise felling range of between 1596 and 1605 for the painting’s oak panel, suggesting that work on the final painting, like the upper paint layer of the oil sketch, could have begun immediately after Rubens returned to Antwerp from Italy.35

The relationship between the painting’s pentimenti and the motifs found in the drawing have been discussed by Held and Freedberg, who noted the presence of the saint’s raised arm, the attendant figure shielding his eyes, and the central shying horse in both the first design for the painting and in the drawing (figs. 22 and 23).36 Our examination, however, has discovered that the initial version, revealed beneath the full-scale painting, had much more in common with the preparatory drawing in every element of the scene.

The camel train seen in the oil sketch and drawing had initially been included in the full-scale painting, as indicated by the long neck of a camel visible as a gray silhouette in the IRR (fig. 24). Its rider, with one arm on his hip and the other raised, can also be identified. Further study of the x-radiograph reveals the presence of a woman with two children strapped to her torso, and a composite image of both X-ray and IRR (fig. 25) shows that their relative positions exactly mimic the drawing (fig. 26). We can refer to Rubens’s first painting of the Conversion of Saint Paul scene to imagine how these painted camels might have appeared (see fig. 4), or perhaps to the 1609 Adoration of the Magi (fig. 27), which also features a retinue of camels.

The IRR also reveals a further rider in the middle distance, silhouetted against a light patch of sky to the left of the camel group (fig. 28). The possible existence of a long train and a distant vista, like that in the drawing, is also suggested by dark patches reminiscent of smaller figures at the left-hand side, as well as shapes on the horizon suggesting buildings.

Rubens, The Conversion of Saint Paul (fig. 1), microphotograph detail (A2) from the sky showing the dark, azurite-containing paint applied over the lighter, ultramarine sky in broad brushstrokes that do not conform closely to the cloud forms at the left edge. The shape of the brushstrokes suggests the use of a flathead brush typically used for spreading paint quickly and evenly.

[IIIF multi-mode viewer]

Rubens, The Conversion of Saint Paul (fig. 1), microphotograph detail (A2) from the sky showing the dark, azurite-containing paint applied over the lighter, ultramarine sky in broad brushstrokes that do not conform closely to the cloud forms at the left edge. The shape of the brushstrokes suggests the use of a flathead brush typically used for spreading paint quickly and evenly.

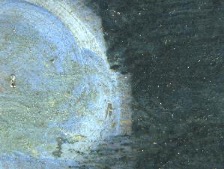

[IIIF multi-mode viewer]The sky was initially painted a pale, bright blue, using ultramarine. This can still be seen at the edges of forms, particularly the clouds (figs. 29a and 29b). Azurite paint was then brushed rather raggedly over this sky, eliminating the distant vista and the camel train. This dramatically altered the tone of the sky, placing the divine apparition in higher contrast and shifting the scene from day to night. This treatment of the sky mirrors the changes made to The Fall of Phaeton, where the paler, ultramarine sky was rather carelessly and rapidly applied around the figures over the original, blackish sky paint.37

In the center middle ground, the X-ray clearly indicates the central shying horse of the drawing, which was initially eliminated by the repainting of the sky and then subsequently replaced by the white horse with a pink mane, seen in sideview (figs. 30–34). The introduction of this horse in sideview also necessitated changes to the bay horse on the extreme left (fig. 35): the bay horse was originally conceived in a more dramatic pose, with its head lowered to the ground as it bucks its rear legs (as in the Liechtenstein picture, see fig. 4), which would have clashed with the forelegs of the white horse. The rider’s left arm can be seen more fully in the X-ray, with his fist gripping the reins that stretch down to the horse’s lowered head (fig. 36). His right arm also appears more dramatically posed, reaching out of the picture plane with fingers splayed, encircled by swirling draperies. This figure would have formed a more direct mirror to the rider whose horse runs forward at the right, with the two together forming the dueling horses group that was originally planned on the right hand side of the drawing (see fig. 19).

As noted by Freedberg, in the middle ground alongside the rider at the extreme left, the X-ray reveals a second painted-out figure, who is looking upward, apparently wearing a turban (see fig. 36), now also visible in the IRR.38 This figure was originally riding a horse whose head was placed where the head of the bay horse on the left-hand side now appears (see fig. 35). A preparatory drawing (fig. 37) for one of the turbaned figures found on the right of the final painting is found on the same sheet as figures for the Adoration of the Shepherds in Fermo. This drawing, reversed, could equally form a model for this revealed figure at the left (fig. 38).39

The group including Saint Paul has undergone numerous radical changes, only some of which have been described previously. The present group differs principally from the oil sketch and drawing in the position of the saint, who is shown in a strongly foreshortened pose, face brightly lit by rays of light, almost spilling out of the picture plane. Yet, in the X-ray, an arm can be seen rising from what is now the center of his torso (see fig. 23). This is not the saint’s right arm but his left, as indicated by the position of his thumb, and so this cannot be explained as a simple alteration to the saint’s arm position. Comparison with the drawing suggests that the saint was originally lying across the picture plane. In the X-ray, the saint’s bent right leg can be seen around the rump of the horse, hooked into drapery in the same manner as the preparatory works. Using IRR, this drapery can be identified as an animal skin, distinguished by leopard spots that appear dark across the rump of the horse (fig. 39).

This animal skin is subsequently reinstated in a new position to indicate the saint falling sideways rather than backward from his horse in the final painted image. The former position of the saint’s head cannot be readily distinguished on the X-ray, but what may be the outline of his helmet is partially visible through the upper paint. It is clear that the position of what is now his left arm was something of an afterthought, painted only thinly on top. It may be that the position of this arm approximates the original right arm of the saint, as seen in the drawing and oil sketch. Alterations to this area and the interlocking arms of the saint and muscled attendant can be seen in the IRR, where underpainting for drapery is apparent beneath the current positions of the saint’s and attendant’s arms. The blue drapery paint of the saint’s clothing runs over paint of a different design in yellow, and what is now the saint’s left leg is painted on top of the drapery of the groom in red. His right arm is finally indicated in thin and sketchy strokes, over a dagger that would originally have hung from a belt at his hip (figs. 40a-d).

This radical alteration of the saint’s position required wholesale changes among the attendant figures. The groom in red originally had more billowing drapery, continuing out to the left of his body in a pinker shade. The armored central figure was added at the last moment to fill the gap created by the repositioning of the saint’s outstretched arm and shows drying defects that are typical of a paint layer applied over thick underlying layers (fig. 41).

The muscled figure to the left was originally dressed in a red robe with yellow highlights, with his left arm raised to shield his eyes. His drapery billowed out from his arm and is visible in both raking light and the X-ray (see fig. 23). His legs may have been in a different position—a circular knee shape can be seen on the X-ray, and his loincloth drapery is extended out at the left in the final composition. There is also some evidence in the IRR that the second, naked attendant of the drawing appeared in the first conception of the painting (fig. 42); while in raking light, draperies can be seen running underneath the legs of the bucking horse at the extreme left (figs. 43 and 44). These would seem to be too far over to belong to the first design of the muscled figure, suggesting an additional figure was laid in but abandoned.

The saint’s horse has been made larger and more monumental at both the right-hand contour of his neck and his foreleg. This rich brown paint has wrinkled as it dried over the pale background paint beneath. Similarly, the dog has been enlarged (fig. 45). These changes may have followed alterations to the two rearing horses behind them in the middle ground, which are used in a number of other works, notably The Fall of Phaeton, but do not appear in the preparatory studies. Again, this shows the synergy of Rubens’s ceaseless revision of his compositions, which allowed ideas from other subjects being tackled concurrently to feed into his creative process.

The figure in yellow, attempting to restrain the dapple-gray horse, was originally climbing onto or falling from its back; his right leg can be seen over the horse’s rump in the X-ray image. Under the microscope, vestiges of painted drapery and flesh can be seen beneath the upper gray paint of the horse (fig. 46). This scrambling figure seems to be related to the individual attempting to clamber onto a camel in the preparatory drawing, which has been erased with bodycolor (see fig. 18b).

With the figure in the earlier position, there would not have been room for the brown foreleg of the right-hand horse on the gray horse’s back, and this leg was clearly a last-minute change. The brown horse was originally shown with a much more muscular, wide neck, with the reins disappearing around the neck to the left, visible in IRR. The mane billowed up and to the right in a manner that strongly echoes the horse pairings in The Death of Hippolytus and The Fall of Phaeton; comparison of the IRR and X-ray images identifies strong, pale highlights and dark streaks in the mane (fig. 47).40 The costume of the brown horse’s rider has also changed. The triangle of gray drapery at his left shoulder is painted thinly over the green drapery as a last-minute addition—probably in response to a change in the horse’s color from dappled gray to brown, as identified by Gifford.41 His right forearm appears as a strong highlight in the X-ray, suggesting it was originally painted bare. This adjustment may have been made once the sky was darkened and the fall of light became more strongly chiaroscuro.

The figures of Christ and the putti have been attributed by Held to a campaign of changes dating to around 1620,42 but, as noted by Freedberg, it is clear from the X-ray that the figure of Christ was planned at the outset with his right arm raised, in a pose that rotates the equivalent figure in the early Liechtenstein version of the scene and is exactly followed in the later Ashmolean oil sketch (figs. 48 and 49). Christ’s arm is subsequently moved down and painted over the highlights of the clouds below, while the dark gray clouds to the right are brought up to cover his torso and some red drapery. The putti appear to be on top of the clouds (see fig. 29b) but were painted before the dark azurite sky, so they must belong to an intermediary stage.

The X-ray of this area reveals the presence of a wooden strip added along the top, with a similar addition found at the bottom (fig. 50). Together these additions increase the height of the painting by about 60 millimeters. Rubens is known to have altered and extended his panel dimensions during the painting process, as has been particularly documented in his landscapes,43 so it seems feasible that this extension could have been undertaken by the artist himself, or at his request.44 The reverse of the panel has not been significantly thinned or altered and retains the original sawing and smoothing marks. A notch has been cut along the two vertical edges of the painting and continues across the full dimension of the reverse, including the added strips (fig. 51). This may have been carried out with the intention of further extending the composition with cross-grain additions on either side—this notch would then form part of a half-lap joint, typically found in such additions.45 However, this technique is also associated with fitting panels into a frame, and a similar thinning at the vertical edges, thought to relate to the original framing of the panel, is found on the reverse of the Antwerp Adoration of the Magi, painted in 1624.46

The two added strips are prepared with ground layers that are different from and less X-ray–dense than the rest of the painting but similar to each other, again typical of what is found in Rubens’s studio extensions.47 Close examination of the X-ray and IRR images suggests that the paint of the sky at the top left, where it meets the newly added strip, was partially scraped away and subsequently reprimed and repainted—a feature also identified on other panels extended by Rubens.48 Importantly, no ultramarine underlayer is found on the upper strip (see microphotograph A10), which means that the extension was made after the decision to alter the sky’s tonality and therefore links the change in dimension to this significant revision. The subsequent paint layers utilize seventeenth-century pigments and are consistent with the materials used to rework the rest of the painting, suggesting they constitute early alterations to the format by the artist himself. In particular, Christ’s red drapery can be seen to extend over the added strip at the top.

The motivation for the change in format and subsequent alterations, particularly to the mood of the sky, might be explained by the suggestion, put forward by Seilern, that the painting (fig. 52) was a pendant to The Defeat of Sennacherib, then dated 1615 (fig. 53). The paintings share a common provenance, having been together in the collection of the Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm (r. 1690–1716) before ending up in the Alte Pinakothek in 1836, and were only separated in 1938 when The Conversion of Saint Paul was purchased by Count Seilern.49 The Defeat of Sennacherib is almost the same size as the enlarged Saint Paul panel.50 Count Seilern considered that the two compositions “were conceived as two halves of a single overall composition,” although there is no physical evidence for this ever having been the case. Nevertheless, the two pictures are, as the Rubenianum entry points out, near–mirror images of each other when The Conversion of Saint Paul is placed on the left.51

The idea that Rubens may have been prepared to offer or even alter preexisting paintings as pendants for other standalone works might have a precedent in the artist’s 1618 correspondence with Sir Dudley Carleton, the British ambassador to the United Provinces who became a collector and intermediary for a British aristocracy looking to acquire Flemish art. In a letter dated May 12, Rubens offers Carleton a painting he has for sale in his studio, A Hunt with Cavaliers and Lions, to complement a hunting scene Carleton had already acquired the previous year. Rubens promises that he will make the work, started by one of his pupils, “as good” as Carleton’s Hunt with Wolves and Foxes so that they will “go very well together.”52

The subtle change to the dimensions makes little significant difference to the Saint Paul composition itself, but it does make it equivalent in size to the Sennacherib panel. In addition, the changes to the sky both alter its tone to make it more consistent with The Defeat of Sennacherib and align the two compositions’ horizon lines, with the elimination of the busy distant camel train. Likewise, the alterations to the figure of Saint Paul make his pose much less similar to that of the fallen foreground figure in The Defeat of Sennacherib, which otherwise might have appeared rather repetitive. Deliberate differentiation from the Sennacherib painting might also account, in part, for the alterations made to the drapery of the green-turbaned figure astride the tussling horse in the middle ground and the change of the color of his horse from dapple gray to brown. By the time these revisions were made, the Courtauld Saint Paul composition may have been languishing in the studio for several years, which was not necessarily an unusual situation—some works listed for sale in the 1618 letter to Sir Dudley Carleton can be dated to ca. 1611–1612, ca. 1614, and ca. 1614–1616.53 It should be acknowledged that, in this instance, more pragmatic motivations, such as finding a buyer for the painting, may have been at play alongside any creative impetus. It is difficult to date the changes in composition on stylistic grounds, but the unusual, upside-down, foreshortened pose of Saint Paul does not appear elsewhere in Rubens’s work until The Battle of Milvian Bridge and The Death of Maxentius in 1620 (fig. 54), and it is notable that this pose is rejected in the later Ashmolean Conversion of Saint Paul (ca. 1616–1620), in which the artist returns to the side view of the oil sketch and drawing. Similarly, the horse seen moving sideways at the left is reminiscent of the horse moving off to the right in A Lion Hunt (fig. 55), perhaps also supporting a date more equivalent to The Defeat of Sennacherib for these changes.

Certainly, Rubens had no qualms about considerably reworking compositions that had remained in his studio for long periods, as has been demonstrated by Gifford’s study of The Fall of Phaeton, in which revisions include changing the lighting and sky, erasing the fiery conflagration of the chariot and zodiac forms, and inserting an additional horse.54 It is also interesting that The Fall of Phaeton has been proposed as a pendant for Hero and Leander, based on both their material similarities and their compositional symmetry.55 As Gifford states, Rubens is not known for his production of pendants, but perhaps this is an area that should be reconsidered. Certainly, Rubens would have taken into account the domestic settings intended for his pictures, as is demonstrated by his private commission for Nicolas Rockox, Samson and Delilah (ca. 1609), in which the modeling and foreshortening of the figures and general perspective was devised to be seen from below, with the painting hung high above the seven-foot mantel in Rockox’s “great salon.”56 The artist clearly thought about how the two hunting scenes offered to Dudley Carleton would have complemented each other, mentioning in his letter the contrast between the European hunters of one and the Moorish and Turkish riders of the other.57 Likewise, the contrast between the New Testament salvation depicted in The Conversion of Saint Paul and the vengeful God of the Old Testament in The Defeat of Sennacherib would have made a good theological pairing. All of these factors appear to have come into play in the revisions made to the Courtauld’s suite of Saint Paul works and support the idea that the final painting was altered to turn it into a pendant for the Sennacherib composition.

Conclusion

It would appear that both the Courtauld’s oil sketch and at least the first conception of its final Conversion of Saint Paul painting belong to the period of around 1608, when Rubens returned to Antwerp from Italy. The drawing has usually been dated to 1610–1612 on stylistic grounds, although perhaps the horses found on the underlying sheet might support an argument for an earlier date, reminiscent as they are of the British Museum study of Greeks and Amazons, usually dated to 1602 (the paper additions, as with the painted changes on the final painting, could belong to a much later stage in Rubens’s career). The drawing shows clear evidence of having been composed within a sketchbook, rather than subsequently bound into a volume, suggesting that the artist retained a sketchbook of compositional designs that he could have revisited and revised over a number of years.

The changes and innovations of The Conversion of Saint Paul, as it was finally completed, show Rubens simplifying the scene with fewer characters, and as such the work could be seen as an intermediate step toward the more intimate grouping of the Ashmolean oil sketch and lost Berlin painting of the same subject. However, some revisions of the composition, including the change in the position of Paul and the lowering of Christ’s arm, are unique to this work and were abandoned in the later paintings. It seems likely that these changes were prompted by reworking the painting for display alongside The Death of Sennacherib, to address the specific visual challenges created by the juxtaposition.

Thus, this small group of works gives considerable insight into Rubens’s working processes: his sometimes pragmatic approach to the reuse and sale of his works, his interest in integrating classical and Renaissance prototypes into his compositions, his reliance on sketchbooks, and, most important, his constant reworking of valuable studio material in his return to favored subjects throughout his career. Viewed together, the Courtauld’s Conversion of Saint Paul works demonstrate Rubens’s creative drive and ceaseless experimentation across all formats—drawings, oil sketches, and large-scale paintings—without the notion of hierarchy that might have prevented other artists from repainting completed pictures.

Exploration and Resources

Annotated image with microphotographs—Rubens, The Conversion of Saint Paul (painting)

Overall images of The Conversion of Saint Paul Series (painting, oil sketch, preparatory drawing)

Manifests of IIIF images

Thanks to the largesse of the University of Heidelberg, HeidICON offers all three versions of The Conversion of Saint Paul (painting, oil sketch, drawing) that can be used in other IIIF viewers such as Mirador.

The Conversion of Saint Paul (painting) manifest: https://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/manifest/iiif/1284726/manifest.json

The Conversion of Saint Paul (oil sketch) manifest: https://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/manifest/iiif/1284730/manifest.json

The Conversion of Saint Paul (drawing) manifest: https://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/manifest/iiif/1284734/manifest.json