This essay examines Northern visual culture within and outside art history, particularly in relation to the work of radical Black feminists, Critical Race Theorists, and contemporary artists working in the African diaspora. Instead of providing an overview of writing about race and enslavement within art history, we primarily—and selectively—examine scholarship and artistic interventions beyond art history to consider the need for new methods with which to address the ongoing legacy of race and colonialism in early modern art, the academy, and the museum.

To state at the outset that this essay is written by two scholars, one of whom identifies as a woman and is white and the other who identifies as a queer woman of color, is central to our undertaking. It matters that here we write collaboratively, admitting diversity into the premise of authorial singularity. We seek to counter the mythos that positionality is irrelevant to scholarship and, worse, that whiteness is somehow synonymous with objectivity, while non-whiteness admits the subjective in a manner antithetical to bona fide historical research and writing. We know we are not alone. Scholars of a new generation—or a newfound orientation—are demonstrating the ways in which privilege and whiteness have constructed histories that cultivate anti-Blackness and pervasive structural and systemic racism. We are indebted to the extraordinary work of so many past and present artists, thinkers, writers, scholars, and theorists, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, and we present our notes and queries in the spirit of conversation.

This essay is a modest and necessarily brief consideration of anti/Blackness as it pertains to the field of Netherlandish art in particular. Our focus is not the inclusion or elision of (depictions of) people of color in Northern art history as written by white scholars. Put another way, addressing histories of slavery and racism in/and Dutch and Flemish art is not solely about recognizing the presence of Black figures in Northern images, although this remains an important topic. We acknowledge our positions at the outset to suggest that how we and others are perceived, or identify, has structured our ability to publish, find jobs, and succeed within academic structures. Operating out of established intersectional frameworks for understanding race and gender, we want to underscore the centrality of Black people, Blackness, and the slave trade in lived histories of the Low Countries and their cultural production.

At the same time, we wish to emphasize the role of white people, white institutions, and the privilege of whiteness in creating and benefitting from an economy dependent on settler colonialism and the buying and selling of people as chattel property. In highlighting scholarship that connects representations of Blackness and Indigeneity in the Americas to enslavement and disenfranchisement, we hope to move beyond apologetic and reductive arguments for “positive” or “negative” representation of Black and Brown bodies to ways of seeing and describing the colonizing white gaze as such. The authors of the catalogue for the Slavery exhibition at the Rijksmuseum (2021) registered “a palpable wish among many of the interviewed researchers to raise the level of the research and debate at home by encouraging engagement with conceptual and methodological discussions.”1 This essay does not seek to supplant extant scholarship underway in this area; Enrique Salvador Rivera, for example, has already published a trenchant critique of the erasure of slavery from histories of the Dutch Atlantic.2 We offer it instead as the departure point for deeper and broader conversations about the study of Northern art within the discipline of art history and our ability as art historians to examine the imbrication of anti-Blackness in its formation as well as its current constitution and practices.

Critical Approaches to the Archive

Since the publication of the first volumes of the monumental series The Image of The Black in Western Art in 1960, art historians have written about race and slavery in Dutch and Flemish art primarily in relation to representational art and portraiture, with less theoretical attention to the archive and its construction. Recent work in the archive has reshaped how scholars understand urbanism and demographics in major art centers such as Amsterdam. This work has reconceptualized the discipline in necessary and exciting ways. Yet the practice of white writers “giving voice to” Black subjects is fraught. The archival turn requires not only studying the archives of slavery but also interrogating the presumed objective facticity of the archive by elucidating how modes of description, citation, and repetition of sources perform and perpetuate biased and insensitive discourse.

Through a method termed critical fabulation, Saidiya Hartman has offered one of the most influential scholarly approaches to (working within) the archive of slavery.3 Critical fabulation allows for affect, unidentified voices, and the recognition of loss to emerge from a body of documents dominated by account ledgers numerically demarcating the cost of human lives. In response to the lightning existences that flash across a ship captain’s log—beings-as-objects who may also appear in paintings, drawings, and prints—Hartman suggests a process by which to mitigate the empirical taxonomies central to creating the white European narrative around slavery. While fundamental scholarship such as Alex van Stipriaan’s Op zoek naar de stilte: Sporen van het slavernijheden (2007) addressed the silences of the archive,4 Hartman’s method foregrounds absence and elision, addressing the extreme difficulty of working within an archive formed by unspeakable omissions, visceral descriptions of heinous acts, and an objectifying, often sexualizing, gaze—without repeating those forms of violence in one’s own historical writing and teaching. To be clear, this can mean limiting the time an offensive image is projected; it can mean encouraging students to acknowledge the historical context of race-based violence and slavery; it can mean openly recognizing the ways students of color may react to seeing Black and Brown bodies represented in dehumanizing ways as they sit in majority white classrooms.

In Lose Your Mother, her account of traveling the west African coast to pursue “the afterlives of slavery,” published almost fifteen years ago, Hartman enumerates a dense list of facts still inexplicably obscured in histories of early modern art, even in explicit discussions of seventeenth-century imagery of the slave trade. Hartman lists a brutal vocabulary that remains untranslated in visual terms, calling particular attention to the language of the Dutch archive. The female slave hold, she writes, was called the hoeregat (whore-hold); enslaved people were demarcated by kop (as in a head of cattle) instead of hoof’d (human head). She continues, “A consignment of slaves was called armazoen, which meant living cargo, as distinct from other kinds of goods, and . . . the Dutch used the term ‘Negro’ as an equivalent to ‘slave,’ so they called the slave ship a neger schip.”5 Among the ways she reframes the recalcitrant archive, Hartman imagines, indeed experiences, the impact of its recapitulation on readers and viewers “like her.” But as in Toni Morrison’s critical account of whiteness and the literary imagination from 1992, Hartman also grants the importance of situating the impact of racism on those who enact it. What Morrison wrote some thirty years ago is no less true today: “It seems both poignant and striking, how avoided and unanalyzed is the effect of racist inflection on the subject.”6 As Hartman and many others demonstrate, breaking the cycles of cruelty and anti-Black bigotry inscribed in language—no less than imagery—demands new methodological forms.

In promising acknowledgments of the need for change, scholarly societies such as the Historians of Netherlandish Art and Renaissance Society of America both released Black Lives Matter statements in the spring of 2020 in the midst of a global pandemic. Institutions once seen by some as separate from the formation of structural racism now struggle to recognize and articulate their role in perpetuating white supremacy. The Historians of Netherlandish Art, in particular, acknowledged the role of visual culture in forming the history of racism, stating that “the images and histories that we study have been and still can be weaponized in the name of racist agendas.”7 Obliquely, this statement points toward a long history of representations of Blackness, enslavement, and their entanglements with the fields of early modern Dutch and Flemish art. Those fields are beginning in important ways to engage theoretically with the histories of racism that are not only sedimented within their paintings, prints, and visual culture but also, and inevitably, in the institutions responsible for training students and fostering the scholarship of Northern art and visual culture.

Since racism and anti-Blackness are often viewed as constructions of later periods, either the later eighteenth century or modernity itself, the place of colonialism and early modern outlooks in forming these histories is often abdicated. Some might agree with Jean-Michel Massing’s assessment that there was no depiction of “the excesses and cruelty of slavery and, more generally, social inequalities,” because they “were hardly ever the subject of any painting before the anti-slavery imagery of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”8 Yet not only do positions such as Massing’s propose their own interpretive gaze as universal, they also negate the importance of Renaissance and Baroque art as the foundation of a visual language around which mythologies perpetuate. They refuse to recognize whiteness as a construction; they ignore the fact that the art market and the slave market were born together. An outlook of this kind allows anti-Blackness to be viewed as an irrelevant contemporary framework instead of a material and rhetorical history that is integral to the history of art history and therefore requires radical new counter-disciplinary actions and scholarship to undo. The modes of observation and description, and the fantasy of an unbiased scholarly viewpoint from which to historicize, are products of visual cultures born in the seventeenth century in tandem with the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, the development of bookkeeping—account ledgers reducing human life to numbers and statistics—the rise of natural history, and the role and erasure of Indigenous and Black lives in contributing both knowledge and labor to a scientific revolution from which their contributions would ultimately be erased.

Spanish Tyranny and the Reality Effect

To take a well-known example, engravings from 1598 by the Fleming Theodor de Bry after Bartolomé de las Casas’s Short of Account of Destruction of the Indies (1542) are widely reproduced by scholars and curators as quasi-journalistic accounts. As premodern images of spectacularized violence against Brown and Black bodies, however, De Bry’s prints might be examined productively as precursors to viral images of Black pain in modern and contemporary media.9 Racial visibility, no less than invisibility, is a difficulty particular to art history and adjacent disciplines built on formal analysis.

Iconoclastic Protestant publishers and artists produced the images accompanying Las Casas’s text in Northern Europe in order to make visible the violence of Spanish forces against Indigenous populations. Already in the seventeenth century, Dutch theorists and humanists were acutely aware of the ethical problems of the slave trade, not least for a community built on the rhetoric of vrijheid, or freedom from Spanish tyranny. Dutch humanists and later political theorists often drew parallels between the Spanish occupation of the Americas and the occupation of the Low Countries, acknowledging the ethical danger of conquest. In his panegyric to the brief Dutch occupation of Brazil, Caspar Barlaeus also recognized the contradiction of decrying tyranny while engaging in the trade of humans as chattel property: “We as well have returned to the practice of buying and selling man, even though he is the image of God and redeemed by Christ, the master of the universe, and anything but a slave because of a fault of nature or intellect.”10 The humanists and later political theorists of the Dutch Republic, therefore, were not oblivious to the fact that their own free trade was borne on the back of an economy increasingly dependent on the enslavement of others in distant plantations. Yet more often than not, histories of Dutch art exclude any mention or discussion of slavery, despite its prevalence in not only the transatlantic world but also the Indian Ocean.

Both of the US-based, American authors of this article are oriented toward the Atlantic world and the scholarship produced in relationship to the transatlantic slave trade; here we are also primarily invested in the legacies of African slavery and anti-Blackness. This orientation should not suggest that slavery within the East India Company and Dutch territories in the Indian and Pacific Oceans is not relevant or vital for comparative studies. Yet rather than assume a transposable condition of enslavement across the early modern world, we recognize that its conditions and circumstances remained distinct within different geographic areas, and we are primarily focused in our own scholarship on the plantation economies in the Americas.11 We regret that in doing so we are perpetuating a lacuna in Dutch scholarship on colonial slavery in Asia—which is, however, being addressed by scholars such as Reggie Baay, Markus Vink, and Matthias Rossum.12

Seventeenth-century Dutch art, above all, remains dominated by the tradition of the “reality effect,” which most recognize as a carefully constructed image giving the impression of photograph-like immediacy dependent on a meticulous and detailed rendition of the visible world. Although many scholars have demonstrated the omissions within this sanitized vision of seventeenth-century Dutch society, art history dedicated to the Low Countries nevertheless remains dominated by certain related tropes: the optical, the interrelationship between art and science, and empirical artistic practice as inseparable from the production of knowledge.13

This is the crux of the relevance of the field of Dutch and Flemish art history to contemporary debates within the field about decolonization. Seventeenth-century Dutch painting is often seen as a precursor of contemporary art because it developed in relationship to a proto-capitalist global economy that created one of the first art markets driven by an emergent middle class. Nevertheless, while other disciplines have spent decades uncovering the role of slavery in the formation of modernity, seventeenth-century Dutch art history is only beginning to consider the role of the transatlantic slave trade in this regard.

Although W.E.B. Du Bois coined the phrase “double consciousness” in 1903, the academic field of Critical Race Theory finds its origins in the legal scholarship and activism of Derrick Bell and Kimberlé Crenshaw at Harvard in the 1980s. Intersectionality, a key term deployed frequently in academic scholarship today, began in the 1980s when Crenshaw, a legal scholar, coined the phrase to articulate how race and gender are not mutually exclusive categories for navigating social and judicial systems. Crenshaw demonstrated that feminist and antiracist discourses often did not speak to the particularity of being a Black woman under threat in America. While intersectionality is now used widely to describe the multidimensionality of identity, it was originally conceived to designate structures of power as existing not only along a single-axis (race or gender) but along multiple axes of discrimination and exclusion.14

Calls for racial and colonial reckoning have come somewhat later to the field of art history. The need for work in this arena was addressed indirectly by Mariët Westermann almost twenty years ago in her magisterial review of the state of the field, “After Iconography and Iconoclasm: Current Research in Netherlandish Art, 1566–1700.”15 Westermann contended that the field of Netherlandish art was energized by the identity politics of the 1970s, which revealed how Erwin Panofsky, Bernard Berenson, and many others assumed a universalist approach to objects and studies, which she identifies as Western and middle-class. Then as now, Westermann noted that the field is a little behind the curve in considering the “social context of art,” acknowledging that race remains an overlooked subject in Dutch cultural studies and citing “the utopic dream of seventeenth-century Dutch tolerance.”16 While historians have extensively debated the “profit margins” of the slave trade on the Dutch economy, scholars such as Karwan Fatah-Black and Matthias Rossum, among others, have demonstrated broader aspects of the role of the slave trade within the economy, particularly in supporting other labor sectors, such as the insurance industry or ship building.17 In turn, although the precarity of Black lives and the need to confront the presence of white supremacist monuments has been selectively addressed across the United States, central monuments of Dutch art have yet to be revisited. A key example is Rombout Verhulst’s tomb of Michiel de Ruyter (and the subsequent painting of the monument by Emanuel de Witte), who played a key role in furthering the Dutch position and interest in the transatlantic slave trade; the monument remains in place at Amsterdam’s Niewe Kerk and the painting is on view at the Rijksmuseum.

Innovative projects in the Netherlands and Belgium are nonetheless beginning to reconceptualize not only the countries’ own histories but also how research and exhibitions should be presented and debated more broadly. These initiatives openly acknowledge that universities, museums, collections, and tourism in the Netherlands and Flanders formed in relation to economies built from exploitative trade and slavery. To counter a violent tradition of disregard and excision from art history’s archives, it is necessary to foreground voices and scholarship that operate within and outside of institutions undergirded by the legacies of slavery, whether through their endowments and collections or the disproportionately low presence of students, faculty, and curators of color. Increasingly, the myth of “golden age” tolerance has been most explicitly questioned in museum exhibitions.18

For example, Black in Rembrandt’s Time (Museum het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam, 2020) introduced a general audience to archival work on the free Black community in Amsterdam formed around the Jodenbreestraat. This important exhibition provided a historical grounding for the growing numbers of depictions of Black people in Dutch painting, disentangling historical presence from stereotypes or exoticism and suggesting a vantage point from which to tell a story about Blackness in the seventeenth century that was not necessarily determined by enslavement.19

And yet the position that this kind of approach takes—that such a disentanglement is ever or truly achievable and that, in certain colonial-era scenarios, Blackness and whiteness can be interrogated and understood as distinct from legacies of slavery and racialized violence—is a stance viewed by many Critical Race Theorists as impossible. To appeal to decolonial discourse, a seemingly inevitable move where “the image of the black” in early modern Northern art is concerned, is to accept a world in which “the human” was and continues to be a contested category.20 As scholar Sylvia Wynter writes, “One cannot ‘unsettle’ the ‘coloniality of power’ without a redescription of the human outside the terms of our present descriptive statement of the human, Man, and its overrepresentation.”21 Wynter, a polymath Caribbeanist playwright, novelist, and critical theorist, is also committed to what Katherine McKittrick has characterized as “counterhumanism.”22 What David Scott famously termed her “re-enchantment” of early modern history and periodization—specifically in relation to Columbus’s 1492 voyage—derives from Wynter’s belief that people must “recognize the dimensions of the breakthroughs that these first humanisms made possible at the level of human cognition, and therefore of the possibility of our eventual emancipation, of our eventual full autonomy, as humans.”23

A curatorial framework in this counter/humanistic tradition might resemble the Rijksmuseum’s Slavery exhibition, which narrates the history of slavery in the Dutch empire from the perspective of ten different individuals.24 The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue made progress toward thoughtfully incorporating the voices of enslaved people instead of solely focusing on European colonizers. One of the curators, Eveline Sint Niclaas, notably incorporated a sonic history of enslavement, integrating plantation bells into the exhibition as both disciplinary markers of time and as tools of revolt and resistance. She included oral traditions and songs in her narrative, intertwining material and oral histories as a method by which to confront a silencing archive. This privileging of the sonic articulated alternative approaches within a discipline tethered to visuality as the dominant sense by which to construct knowledge.

The Mauritshuis in The Hague addressed the relationship between their founder—Johan Maurits—and the slave trade in Shifting Image: In Search of Johan Maurits (2019). The researchers for this exhibition, Carolina Monteiro and Erik Odegard, followed up with an important article explicitly linking Maurits’s wealth to the slave trade, countering historians who continue to argue that he did not benefit economically from the development of the transatlantic slave trade.25 This research is part of the European Research Council–funded project at the University of Leiden led by Mariana De Campos Françozo, BRASILIAE: Indigenous Knoweldge in the Making of Science: Historia Naturalis Brasilia (1648).26 As in the Rijksmuseum’s Slavery exhibition, the collaboration focuses on the voices and perspectives of the African and Indigenous Tupi communities in Brazil by considering the contribution to Willem Piso and Georg Marcgraf’s Historia Naturalis Brasilia (1648). These are only a few of the dynamic public projects in the Netherlands today addressing the early modern slave trade and its histories.

Somewhat differently, within the realm of Flemish, art it seems crucial that art historians acknowledge more recent transhistorical and transnational connections between Belgium and the so-called Congo Free State. Another “reckoning” exhibition, the Turvuren Museum’s La mémoire du Congo, le temps colonial (2005), was the inspiration for historian Deborah Silverman’s invaluable delineation of “profound and inextricable ties” between Belgian Art Nouveau and the “patrons, policies, violence, and even the expressive forms of Congo imperialism”—a regime of terror now deemed responsible for the deaths of between four and eight million Indigenous Congolese.27 Today, graduate students and scholars of color routinely face white supremacy not only on Belgian streets but also in the very architecture and fabric of the places we/they study in order to become experts in our field. As Jenny Folsom has noted, the severed Giant’s hands that are emblematic of Antwerp (whose name legendarily derives from the Dutch hand werpen, or hand throwing) eerily anticipate the heinous Leopoldine practice of amputating the hands of Congolese workers who failed to meet rubber quotas.28 The presence of dark chocolate Antwerpse Handjes in market windows today readily evokes the symbolic imagery of Flemish meat stalls by Pieter Aertsen and company; attending to formal and historical links of this sort is an important aim of antiracist pedagogical praxis.

Admittedly, analyzing sixteenth-century imagery through that of the nineteenth—or twenty-first—might be anathema to many pre-modernists. However, working transhistorically offers the possibility of more inclusive and diverse syllabi; it can also encourage students to make novel, previously unexplored connections between the creation and reception of works of art within and beyond their original contexts. Among his invigorating litany of methods, Damian Skinner cites “transnational” and “transhistorical” strategies as necessary for decolonial teaching and research. As a white Canadian studying Indigenous cultures, Skinner challenges art historians to make critical distinctions between “colonialism” and various iterations of “settler colonialism.” In the latter, he notes that “not people but space” is of the utmost importance to the colonizer, who removes populations in order to establish a presence—a weltanschauung that resonates in obvious ways with classic understandings of Dutch picturing in seemingly neutral, depopulated, and deracinated works of art.29

When early modern Northern art history leaves unaddressed the commercial and colonial relationships between and across national and temporal boundaries, our subfield forms a valorizing discourse around whiteness, trade, and tolerance without examining the role of race and enslavement in the formation of capitalism. This critique was raised, though not by an art historian, nearly three decades ago in Allison Blakely’s prescient Blacks in the Dutch World (1993). This wide-ranging exploration of the convergence of Dutch racial imagery and modernization was inspired in part by the notorious controversies around the depiction of Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). Blakely begins what is now a classic of Black studies by begging “forgiveness from the many friends in the Netherlands for whom I have spoiled forever the simple pleasures in visiting museums and art collections.”30

Some eight years later, Susan Buck-Morss cogently examined Western European intellectual history and its paradoxical celebration of freedom within an economy built on enslaved labor. Her article “Hegel and Haiti,” from 2000, begins in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, noting (as had Blakely) the absence of slavery as a subject in works such as Simon Schama’s The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (1987), a study of the Dutch Republic and its contradictory attitudes toward wealth and Calvinism, arguing that this absence in Schama’s scholarship marks an avoidance of enslavement and race within “Western academic scholarship.”31

Nearly a decade ago, in his Slavery and the Culture of Taste (2014), Simon Gikandi related Rembrandt’s painting of two Black men from the local Afro-Dutch community (the centerpiece of the Black in Rembrandt’s Time exhibition) to a seventeenth-century bill of sale for enslaved people, suggesting that the “narrative of modern identity” begins with these opposing documents, which reveal the contradictory “relation between the aesthetic object and the political economy of slavery.”32 Gikandi’s juxtaposition demonstrates how the celebration of an interior self, the emergence of the individual capable of judgment and reason as central to modernity and an emergent visual culture—an assumption that runs deep, from René Descartes to Alois Riegl—is complicated when large-scale populations are denied their humanity or the category of the person. Whether that category admits women and, if so, what kind, is also an important consideration.33

Modern and Contemporary Projects

The critic Patricia Saunders asks, “Can we understand by returning, yet again, to the archive, in the absence of bones, of tombstones, to try to identify and localize the remains of the enslaved?”34 It is perhaps in response to this sort of question that many contemporary artists working in the African diaspora directly cite the pictorial archive of seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting. In her ongoing series Rewriting History, acquired in 2021 by Yale’s Beinecke Library, the Haiti-born artist Fabiola Jean-Louis (b. 1978) creates paper sculptures based on dresses worn in Old Master portraits.35 Whereas the sitters for the paintings were originally white European aristocrats surrounded by the luxury, pomp, and finery of their circumstances, Jean-Louis recomposes the portraits with reminders of the violence done by enslavement to Black bodies and subjectivity. The displays of wealth in the earlier portraits are inseparable in her work from the profitable trade of human beings.

In They’ll Say We Enjoyed it, Jean-Louis knowingly replaces Queen Charlotte from Thomas Gainsborough’s 1781 portrait with a young, brown-skinned woman (fig. 1). Yet—as in sixteenth-century Flemish market scenes—the embedded image in the background is the image’s crucible of meaning. Whereas Gainsborough’s painting recedes into an Arcadian landscape with an architectural folly, Jean-Louis interrupts a pastoral reverie with a violent scene of sexual assault taken from an infamous seventeenth-century Dutch painting: Christiaen van Couwenbergh’s Rape of an African Woman (1632; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg). While Gainsborough absents slavery from the luxurious surroundings it subsidized, Jean-Louis juxtaposes an image of courtly civility with one of early modern art’s most lucidly painted depictions of sexual violence against a Black woman. The inclusion of the rape scene demonstrates that the “rewriting” of art history calls for more than inserting images of people of color into the canon; it requires the willingness to accept, investigate, and challenge the contemporaneous realities and conditions of canon formation itself. Jean-Louis’s rewriting of history demonstrates its limits if we do not make visible the ground of violence on which whiteness is poised.

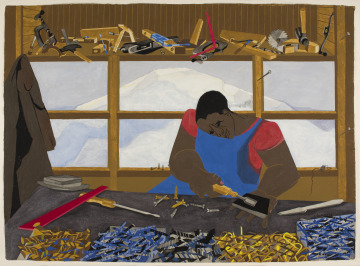

Diasporic artists’ interpictorial modes do not always reveal violent encounters or directly engage with the slave trade. Less obvious relationships and exchanges between modern and early modern artists can be interpreted as conceptual as well as compositional, though this has not often been the case. (The authors are exploring these relationships in their current teaching and research and hope to give them fuller consideration in future publications.) To take two examples, Jacob Lawrence’s (United States, 1917–2000) direct allusion to the Mérode Altarpiece by the workshop of the Flemish artist Robert Campin (1427–32; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cloisters Collection)36 in his Builders # 1 (fig. 2) was vaguely framed at the time as having “evoked in a contemporary form the atmosphere of a carpenter’s shop” by one of the few reviewers to have noticed the connection between the two works.37 Lawrence’s gesture ventures beyond the formal to the chromatic, the iconographic, and the political with the implication that his subject undertakes a sacred kind of work akin to Joseph’s allegorical mousetrap-building. Production and labor are evoked by the crossed hammer and sickle-like red level and screwdriver on the figure’s right.

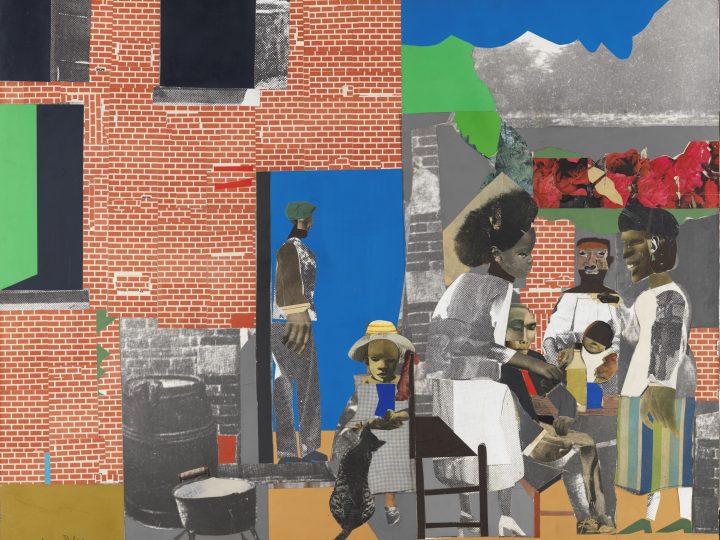

In the case of Lawrence’s contemporary Romare Bearden (United States, 1911–1988), however, the study and engagement of early modern Northern art by a modern artist who is Black was repeatedly voiced by the artist himself. In 1969, Bearden wrote an article for the art journal Leonardo explaining the structural principles of his “montage paintings.”38 Thanks to the GI Bill, Bearden had studied a wide range of Renaissance and Baroque art during his eighteen-month stay in Europe, when he was based in Paris. On returning to the United States, however, it was to “the Dutch masters” that he looked for pictorial strategies for managing shapes and scale in his collaged works. Bearden’s formal and sociopolitical interest in redbrick courtyard settings is fascinating to consider in relation to the genre scenes he depicted while living and working in the “other” Harlem, located in the former New Amsterdam that is today New York (fig. 3). As he put it: “I want to show that the myth and ritual of Negro life provide the same formal elements that appear in other art, such as Dutch painting by Pieter de Hooch.”39

Whether at the level of form or content, modern and contemporary diasporic artists’ encounters with early modern Dutch and Flemish art allow us to think art historically about Blackness and anti-Blackness. Black Feminism and Critical Race Theory call for new methodologies to counter ongoing forms of violence. Art history’s needful dismantling cannot happen within houses built from colonial resources, extraction, and exploitation.

We write this article from the land of the Abenaki (Vanessa in Bennington) and the Stockbridge-Munsee (Caroline in Williamstown). This land also borders the Hudson River Valley, where the Dutch set up colonial trading posts during their brief colonization of New Amsterdam, as testified to within the African Burial Ground in New York City. We cannot disentangle this history from our current positions, yet the histories we teach and read and write can and must change in acknowledgement of this fact.