Since technical research revealed that the center panel of the Mérode Altarpiece is based on an Annunciation in Brussels and that the wings were added at a later stage, the painting has lost its status as a key work in both the oeuvre of the Master of Flémalle and the history of painting. Analysis of artistic and iconographic elements of the Mérode Annunciation in comparison to the Brussels Annunciation, however, shows that the image should not be considered a less important work than its model but a product of choices and intentions aiming to optimize its function as a visual accompaniment of a personal prayer practice. Compositional and iconographic discrepancies between the wings and the center panel suggest that the work was transformed into an altarpiece with a specific devotional intention.

Changing Opinions

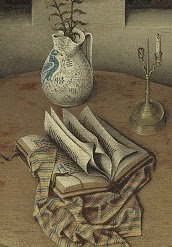

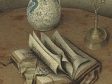

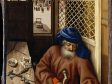

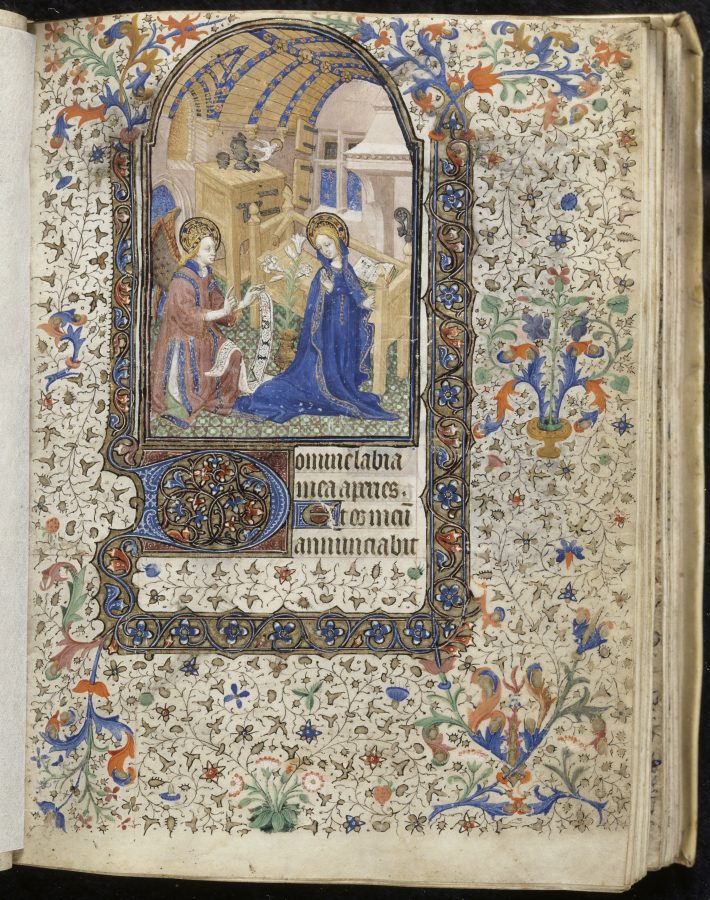

Probably no other painting illustrates as well as the Mérode Altarpiece how art-historical constructions based on connoisseurship can be built up only to fall apart later (fig. 1). The remarkable history of the stylistic research into this painting, which shows the Annunciation in the center panel (fig. 2), Saint Joseph in his workshop in the right wing (fig. 3), and portraits of a couple kneeling at the door of the Virgin’s house in the left one (fig. 4), could fill a publication on its own. Here, a concise discussion of this history, focusing on several pivotal points, will serve as an introduction to an alternative approach, according to which the interpretation and appreciation of the artistic qualities of the triptych are not determined by questions of attribution.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Hugo von Tschudi published an article in two parts in which he used the Mérode Altarpiece, owned by the Belgian family De Mérode, and the Flémalle panels in Frankfurt am Main as the key works for the reconstruction of an artistic oeuvre, whose anonymous creator he gave the name “Meister von Flémalle” (Master of Flémalle).1 Striking features of the Mérode Altarpiece are, for Tschudi, the vivid but cool colors and the preference for light and dark, with double- or even triple- cast shadows. Light and dark are used not merely for pictorial effects but also to create depth and to model faces and hands. The vestments of the figures have rich folds, which are well observed and suggest the woven materials from which they are constructed. On the basis of all the assembled works, the Master of Flémalle is characterized as “ein Realist durch und durch” (a realist through and through), which appears in his sense of events, costumes, spaces, and tools. The use of a high horizon gives the interiors a disturbing view from above, but they are represented with unsurpassed faithfulness and simplicity. Tschudi argues that the artist was influenced by both Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, but that when he paints ideal types, especially female ones, he is closest to Rogier, which explains why his paintings are often ascribed to that artist.

In 1909 and 1911, Georges Hulin de Loo attributed, on documentary evidence, panels from an altarpiece made for the abbey in Saint Vaast to Jacques Daret, who with Rogier van der Weyden had been an apprentice of Robert Campin (ca. 1375–1444) in Tournai. The resemblances between the Daret panels on the one hand and works ascribed to Van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle on the other made Hulin identify the latter as Robert Campin himself.2 This identification was accepted by most art historians but heavily contested by Emile Renders, a supporter of the Flemish Movement, which propagated the cultural identity of Flanders. For Renders, the thought was unacceptable that the French enclave of Tournai would have produced the earliest great representative of the so-called Flemish school of painting. In La solution du problème Van der Weyden–Flémalle–Campin, from 1931, he defended the hypothesis that the oeuvre of the Master of Flémalle should be ascribed to Rogier van der Weyden.3 Renders did everything he could to convince Max Friedländer, who in his volume on Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle in Die altniederländische Malerei, from 1924, had drawn attention to the difficulty of establishing a dividing line between the oeuvres of the two masters.4 In a special supplement in the last volume of his series, Friedländer followed Renders’s idea of one oeuvre created by Rogier,5 albeit without attempting to solve the contradiction with his earlier judgment about the Mérode Altarpiece. Then, praising the work’s realism but criticizing the perspective and crowded composition, he concluded: “The statement made in this painting allows its author to emerge clearly as a personality quite distinct from Rogier.”6

In his Early Netherlandish Painting from 1953, Erwin Panofsky fully accepted the existence of an oeuvre that had been reconstructed under the label Master of Flémalle and the identification of the painter with Robert Campin, although he preferred to use Tschudi’s Notname (name of convenience). The Master of Flémalle is the first of the painters whom Panofsky discusses as the founders of early Netherlandish painting, and he assigns a pivotal role to the Mérode Altarpiece not only in the development of the artist but also in the whole history of European art, since it represents a crucial transitional phase, mirrored centuries later in modern painting:

From a diametrically opposite point of view, and with a diametrically opposite intention, the Master of Flémalle achieved an effect not unlike that aspired to by Cézanne and van Gogh. Cézanne and van Gogh wished to affirm the plane surface while still committed to a perspective interpretation of space; the Master of Flémalle strove to affirm perspective space while still committed to a decorative interpretation of the plane surface.7

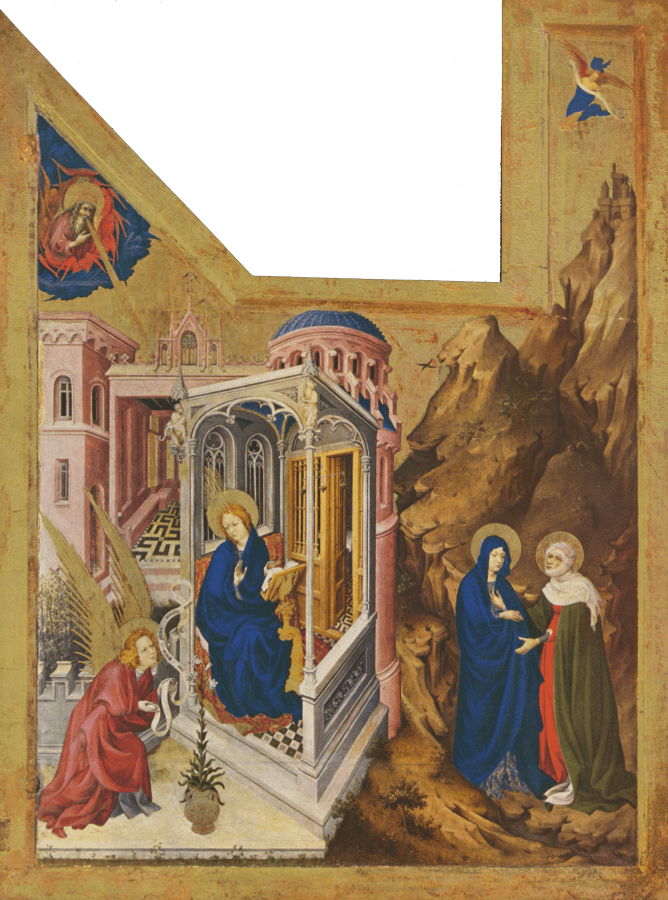

Two years later, however, quite a different opinion was brought forward by Heinrich Musper.8 Instead of considering the Mérode Altarpiece as a key work in Campin’s oeuvre and in the history of art, he saw the center panel (see fig. 2) as a copy after the similar Annunciation in Brussels (fig. 5). The latter painting is in rather poor condition: the faces have been retouched, and layers of glazes have worn away.9 Until then, the Brussels panel had been seen as the copy. Musper acknowledged that it had a more restrained character than the Mérode Annunciation but argued that it was qualitatively better in expression, gestures, and details, so therefore it must be the original.

Panofsky worded his notions extensively, with great rhetorical talent, in a standard work; Musper expressed his orally and had them recorded by the journalist Hans Diebow, under the transparent pseudonym “H. Die,” in a short contribution to the journal Die Weltkunst. During the Nazi period, Diebow had produced biographies on Mussolini and Hitler and anti-Semitic writings. Understandably, Musper’s hypothesis was largely ignored by the art historical world. When, in 1957, the Metropolitan Museum of Art devoted an issue of its bulletin to the Mérode Altarpiece, which it had acquired just the year before, the possible dependence of the center panel on the Brussels Annunciation was not discussed. The curator Theodore Rousseau, who saw Robert Campin as the creator, presented the triptych entirely in the spirit of Panofsky as “one of the key works in the history of painting” and “a milestone between two periods,” since “it at once summarizes the medieval tradition and lays the foundation for the development of modern painting.”10

Along with its innovative qualities, Rousseau praised the superior painting technique of the Mérode Altarpiece, emphasizing how the painter took advantage of the properties of oil and mentioning, among other things, “the transparency of the jewel-like glazes in the Virgin’s robe.”11 The conservator William Suhr, who found the condition of the work excellent, also used the term “jewel-like” for the brilliance of the colors.12 During the cleaning of the triptych, Suhr and Rousseau had made some discoveries: originally, the windows in the Annunciation had a gold ground, just like in the Brussels Annunciation, and in the left wing, the donor’s wife and probably also the man in the background, next to the gate, were added after the picture was completed.13

In his book Altniederländische Malerei von Van Eyck bis Bosch from 1968, Musper repeated his opinion about the relationship between the Mérode and Brussels Annunciations, confining himself to the argument that in the Brussels panel the pose of the Virgin is gothically humble and in the Mérode Annunciation frontal and self-conscious as a harbinger of the Renaissance (figs. 2a and 5a).14 While Musper’s article in Die Weltkunst ascribed the panels to different artists, by now he saw them as both being produced by Campin, and he underscored that in the fifteenth century the concept of “a derivative by one’s own hand” did not necessarily signify a devaluation. Nevertheless, he stated, it was time to recognize the Brussels panel, painted in such a wonderful manner, as a first-class masterpiece, superior to the Mérode Altarpiece.

Again, his view seems to have had little impact, but six years later, independently, Lorne Campbell, too, argued that the Brussels Annunciation was the original composition.15 Contrary to Musper, he was unambiguously negative about the Mérode Altarpiece, observing a variety of deficiencies in it, such as the lack of coherence in the design and colors of both the whole and each part, the curious distortions of the perspective of the Annunciation, the coarse facial types of the Virgin and the angel, their placid impassivity, and the overlapping contours of the table and the angel’s right hand. The center panel seemed to him to be a pastiche, partly based on the better-composed Brussels Annunciation or on a common model, whereas the frontally rendered Virgin could have been derived from another Annunciation, in the Prado, from the Master of Flémalle group of paintings (fig. 6). Campbell attributed the Mérode Altarpiece to a pupil or an assistant of Robert Campin, whom he called the Master of Mérode and associated with a few other panels from the Master of Flémalle group, including The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen in London (fig. 7).

Since then, infrared reflectography investigations by J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer and others, first published by Jeltje Dijkstra, have provided further insight into the relationship between both Annunciations.16 Differences between the underdrawing and the painted surface in the Brussels panel show that a creative process took place during the work’s execution: the positions of certain elements were changed, and motifs that are absent in the underdrawing, such as the door and the brush, were added. In the Mérode Annunciation, on the other hand, most of the architectural elements and objects that it has in common with the other image are either hardly underdrawn or not at all. The underdrawing of the Mérode angel resembles the angel of the Brussels Annunciation but differs in a number of details from the execution in paint. The corbels of the ceiling at the left in the underdrawing of the Mérode panel are also more similar to the ones in the Brussels picture than to their painted versions. These observations leave no doubt that the painter of the Mérode Annunciation followed the other work, and not vice versa.

In his monograph Der Meister von Flémalle: Die Werkstat Robert Campins und Rogier van der Weyden from 1997, Stephan Kemperdick compares the composition and motifs of the Mérode Annunciation anew with the Brussels panel.17 He mentions the lack of harmony of the Virgin in relation to the angel and furniture, the unrealistic large sizes of the laver and towel, and discrepancies in the perspective caused by different points of view. The absence of unity in space gives, to his eye, the impression that the image was partially composed as a collage.

Besides the fact that the center panel of the Mérode Altarpiece is not an original creation, another striking fact has become clear: the work does not seem to have been a triptych from the beginning. Dendrochronology has shown that the wood of the center panel is of a different, earlier date than that of the side panels.18 Together with the discovery of the original gold ground in the windows of the Annunciation, this finding implies that initially the center panel was an independent painting, just like, one assumes, the Brussels Annunciation. When the Mérode Annunciation was expanded into a triptych, its gold ground was replaced by a sky color to coordinate the image with the flanking scenes.19 Somewhat later, the portrait of the donor’s wife and, probably, the figure of the man in the background were added. The side panels were produced not long after the Annunciation was painted. On the basis of the dendrochronology and the couple’s costumes, they can be dated to the late 1420s—that is, the same decade in which the Brussels Annunciation originated, as indicated by the image of Saint Christopher attached to the Brussels fireplace, which reproduces a woodcut from the 1420s.20

Because of the rather short interval between the production of the center panel and the wings, the latter may have been commissioned by the original owner of the Annunciation, but it is also possible that they were ordered by a different person. And, although it seems obvious that the coats of arms were painted on the occasion of the addition of the donor’s wife, it cannot be ruled out that this happened later and that they do not refer to the portrayed couple.21 In any case, efforts to identify these individuals with the help of the coats of arms have not been successful.22 Only the one at the dexter side has been identified with certainty, by Tschudi; it belonged to a family Imbrechts or Engelbrecht, members of which lived in Mechelen and Cologne.23

On the basis of both the underdrawings and the painted surfaces of the three panels, Kemperdick confirms the opinion, previously put forward by Mojmír Frinta, that the center panel and left wing are by different hands, and he even ascribes the right wing to a third painter.24 The left wing, in his eyes, is closest to the Flémalle panels; the right wing he relates to the Nativity in Dijon (ca. 1430; Musée des Beaux-Arts), from the Master of Flémalle group, which shows, as Tschudi had noted, a similar Saint Joseph figure and also shares other features in common. Kemperdick does not connect the center panel with other paintings in the Master of Flémalle group, and he finds no reason to attribute any part of the Mérode Altarpiece to Robert Campin. Although the Brussels Annunciation is more likely to have been painted by Campin, Kemperdick is hesitant about a definite attribution; he considers the name Master of Flémalle a collective name for a group of paintings made by various hands, with the strong participation of Rogier van der Weyden, as a member of Campin’s workshop, in one subgroup.25 Thus, Friedländer’s suspicion seems to have come true: that Campin was “something akin to an entrepreneur who retained capable hands for team work over a long period.”26

Today, the Mérode Altarpiece is catalogued by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as “Workshop of Robert Campin,” which accords with the present insights but makes the painting, for both the majority of specialists and the general public alike, less interesting and valuable than when it was previously ascribed to the master’s own hand.27 The label forms a rather sad contrast with the jubilant words of the former curator, Rousseau, when he introduced the painting to the public as “one of the key works in the history of painting” and “a milestone between two periods.”

As a historiographical survey, this summary of the diverse ways in which connoisseurs have assessed the Mérode Altarpiece is incomplete; however, it suffices to illustrate how the appreciation of its artistic qualities and the question of attribution go hand in hand. In what follows, this close relationship will be disconnected. Accepting the idea that the triptych was produced in the workshop of Robert Campin in various stages, I will discuss its artistic character without regard to the identification of specific hands. Instead, I will explore interconnections between form, content, and function, which implies that I will also pay extensive attention to iconological questions. First, however, let us return to Rousseau and to Campbell.

Appreciations and Approaches

Despite its grandiose introductory remarks, Rousseau’s essay on the Mérode Altarpiece is full of sensitive observations. He ascribes the realism in the work to the pattern of light and color on the objects, rather than to the arrangement of the forms in surface or in depth, about which he remarks:

Here the painter entirely changed and transformed reality to serve his own purpose of making the picture more effective. One of his methods was to make the outline of one form lead directly into another, for instance, the right hand of the angel and the table, thus guiding the eye forcibly from one place to another. . . . These lines play a vital part in the picture’s surface and give it what might be called a visual rhythm.28

The opposite ways in which Rousseau and Campbell appreciate the congruent contours of the angel’s right hand and the table testify to how greatly opinions on the artistic qualities of the Mérode Annunciation are determined by personal taste. One might argue that Campbell’s judgment has more weight, because he was right that the composition is not original. The discovery of its dependence on the Brussels Annunciation, however, is based on insight into how both images were prepared in the underdrawing and has little to do with artistic quality. On the other hand, the status of the Mérode Annunciation as a copy does not automatically imply that its execution is inferior to that of its model. True, the Brussels Annunciation, with its quieter interior, and with the angel and Virgin gracefully leaning toward each other, echoing the circular form of the table, has a compositional harmony that the other image lacks. This does not detract from the fact that the Mérode Annunciation shows the self-assurance of a painter who had great skill in drawing figures and objects and in applying paint layers. Even if the poor condition of the Brussels Annunciation makes a comparison of technical qualities difficult, it is hard to believe that it ever possessed the virtuosic use of light and shadows of the other image.

Moreover, the painter of the Mérode Annunciation made careful choices in the arrangement of elements in the composition. He must have deliberately changed the disconnected contours of the angel’s hand and the table, as seen in the Brussels panel, into overlapping ones (figs. 2b and 5b). A similar alteration occurs in the contours of the back of the bench and the foreshortened underside of the shutter at the right; while they are staggered in the Brussels composition, here they are in line with each other. These contours of bench and shutter form a triangular pattern with the ornament of the towel holder, the back of the angel, and the lower edge of the panel, whereas the towel’s shadow and the right contour of the table leg, which has been shifted to the left in accordance with the oblique view on the table, form the perpendicular of the imaginary triangle. An intention to create order must also have been behind the decision to situate the candlestick on the table and the mullion of the window on the same axis, unlike in the Brussels Annunciation.

These changes were evidently made to compensate for the more crowded interior caused by the addition of the niche with a laver and built-in basin and the towel, which replace one of the windows in the Brussels panel. Another series of modifications derive from the decision to alter the position of the Virgin and to dress her completely in red. Since a large part of her mantle falls across the bench, the cloth lying on the bench no longer covers its back, which is decorated with refined woodcarving. The blue of her Brussels robe is used for the pillow and cloth on the bench, and the lightest accent within the area of the Brussels bench, formed by the yellowish pillow, has been transferred to the new motif of the firescreen, with its light wood color. The loss of green caused by the change in the color of the cloth on the bench is balanced by the green of the storage bag for the book on the table. The storage bag could be used here since it was no longer associated with the book Mary is reading, as in the Brussels panel, where it unconspiciously lies at her feet. The book held by the Mérode Virgin, on the other hand, is provided with a chemise binding, serving as a second cover, like the book on the Brussels table but with a different chemise.29 It can be concluded that, down to the smallest detail, the painter of the Mérode Annunciation reflected on how to relate to his model.

The new iconographic motifs of laver, basin, and towel, and the frontal position of the Virgin and her completely red dress—which are the causes of so many other changes and will be discussed themselves in the following sections—indicate no reasons to see the Mérode Annunciation as a copy made for the free market;30 they must be ascribed to the wishes of a patron. The similar widths of the back wall and windows in both paintings suggest that the Mérode Annunciation is based not on a drawing but directly on its model.31 The patron may therefore have seen the Brussels panel—which, as already pointed out, cannot have originated much earlier than the copy—when it was still in the workshop and have ordered a similar image, but with new inventions.

In the following discussion, I will interpret the Mérode Annunciation as the product of iconographic and artistic choices motivated by specific intentions connected to the painting’s function. For this purpose, I will further analyze it in relation to its model. Subsequently, I will investigate the wings in relation to the center panel.

The Virgin

The relationship between the Mérode Annunciation (fig. 2c) and the Brussels Annunciation (fig. 5c) can only be fully understood by exploring the meanings and functions of the motifs and compositional forms in each painting. Because it is most probable that the works were made as individual panels, they seem to have been intended for personal devotion to the Virgin. In both images, Mary is seated on a cushion, on the footstool of the bench, which recalls the Madonna of Humility, with the Virgin and Child seated on a cushion on the ground. The earliest known example of this theme, which flowered in Italian art before it spread to Northern Europe, is a much-damaged fresco by Simone Martini from around 1341, which along with other images by his hand decorated the entrance porch of the cathedral of Notre Dame-des Doms in Avignon.32 Martini’s Madonna of Humility, in the company of angels and the donor, Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi, was painted in the tympanum, and on the surrounding arch an inscription executed in large letters contained sections of the Salve Regina (Hail Holy Queen). Words from this hymn and prayer are also inscribed on the edge of the Virgin’s mantle in the Brussels Annunciation.33 This fact is remarkable; I am not aware of any other examples of the Madonna of Humility with quotations from the Salve Regina. If this resemblance between the panel and the fresco is not coincidental, it could be explained by an unknown, intermediary visual source. Such a source must have been used, in any case, for applying the theme of the Madonna of Humility to an Annunciation and depicting the Virgin in front of a bench. Both forms of representation occur separately in Sienese Trecento art34 but are brought together in early fifteenth-century Franco-Flemish manuscript illumination. A miniature with the Annunciation in a Parisian book of hours (fig. 8), dated 1415–20 and ascribed to the Master of the Harvard Hannibal, shows the Virgin sitting before a bench in a domestic setting that was further developed in the Brussels and Mérode Annunciations.35

The humility of the Virgin, which was an important subject for theologians, preachers, and authors of devotional writings,36 manifested itself in her behavior at the event of the Annunciation. It was, as explained in the widespread Meditationes Vitae Christi, the cause of her perturbation and silence after Gabriel entered her room and spoke the words, “Ave gratia plena; dominus tecum; benedicta in mulieribus” (Hail, you who are full of grace; the Lord is with you; blessed are you among women; Luke 1:28):

Hearing herself thrice commended in this salutation, the humble woman could not but be disturbed. She was praised that she was full of grace, that God was with her, and that she was blessed above all women. Since humble persons are unable to hear praise of themselves without shame and agitation, she was perturbed with an honest and virtuous shame. She also began to fear that it was not true, not that she did [not] believe that the angel spoke truthfully, but that like all humble people she did not consider her own virtues but memorized her defects, always considering a great virtue to be small and a little defect very big.37

In early Italian paintings of the Annunciation, the Virgin’s disturbance as a sign of her humility was represented very expressively by her recoiling posture in reaction to the angelic salutation.38 In Northern art, this reaction was toned down to an elegant pose, as in Melchior Broederlam’s altar wing with an Annunciation and Visitation in Dijon (fig. 9), and the miniature by the Master of the Harvard Hannibal in the Parisian book of hours, although in both images the Virgin’s raised right hand can still be taken as a sign of warding off the angel’s praise. In the Brussels Annunciation (see fig. 5), however, Mary holds her right hand against her breast as an indication of her submission to God’s will when, after hearing Gabriel’s message, she speaks the words, “Ecce ancilla Domini, mihi fiat voluntas sua” (Luke 1:38). The Meditationes describes how these words are characteristic of the Virgin’s humility:

See how the Lady remains timorous and humble, with modest face, as she is accosted by the angel, not becoming proud and boastful after his unforeseen words, in hearing such wonderful things as had never been told to anyone before, but attributing everything to divine grace. . . . But finally the prudent Virgin understood the words of the angel and consented, and . . . she knelt with profound devotion and, folding her hands, said, “Behold the handmaid of God; let it be to me according to your word.”39

In the Brussels panel, the meaning of Mary’s gesture as an assertion of her obedience is subtly alluded to by the capital E in the book on her knees, which apparently stands for the word “Ecce,” just as the capital A in the book on the table must be a reference to the “Ave” of the angel.40 Thus, the painting illustrates not just a single moment of the Annunciation but instead unites the salutation of the angel with the Virgin’s consent to his message at the end of their conversation, when she humbly calls herself “the handmaid of God.” Thanks to this humility, the Incarnation of Christ became possible, as is made clear in the Meditationes, which after quoting Mary’s final response continues with the phrase, “then the Son of God forthwith entered her womb without delay and from her acquired human flesh.”41

Whereas the essential role of the Virgin for the salvation of humankind resulted from her humility, it resulted in her being honored as the Queen of Heaven.42 Therefore, the words from the Salve Regina inscribed on her mantle in the Brussels Annunciation, which connect the humility of her pose to her regal nature, enrich the devotional meaning of the image. Moreover, like the Ave Maria (Hail Mary), this prayer calls Jesus the blessed fruit of her womb, but it also implores Mary, as advocate for the faithful, to turn her merciful eyes toward humanity and reveal her son when earthly lives have ended. By placing the Incarnation in the perspective of the hope for heaven, the Salve Regina adds to the Ave Maria, the prayer for which the panel must have served as a visual accompaniment in the first place.

Nevertheless, the image is not uncomplicated with respect to prayer practice. Even while representing different moments of the Annunciation, the figures interact with each other, which makes the Virgin more a part of a narrative scene than the addressee of the devotee’s prayers, as in panels of the Virgin and Child. It must have been a conscious decision by the painter of the Mérode Annunciation, at the instigation of his patron, to break the harmonious pattern of the Brussels composition and to present the Virgin in a frontal position. This figure is, in my opinion, an original invention; the Prado Annunciation (see fig. 6) shows a simplified version in terms of the modeling with light and the drawing of the robe, mantle, and chemise of the book. A subtle but significant change during the execution of the Mérode Virgin reveals a creative process, which corroborates the idea of the originality of the figure and also testifies that, initially, the artist hesitated to isolate Mary completely from the angel. As shown by X-ray, in the underpainting she has her head turned slightly to the left and her eyes raised in the direction of Gabriel.43 This pose was apparently found to be unsatisfying—by the painter or by the patron visiting the workshop—so a final step was taken to transform her into a completely independent figure, engrossed in the book she is holding.44

As far as the Virgin is concerned, the transformation of the Brussels composition into the Mérode Annunciation can be described as a development “from narrative to icon,”45 and of “form follows function.”46 Although the inscriptions referring to the Ave Maria and Salve Regina are lacking in the Mérode panel, it is better attuned to prayer practice than its model. Mary is represented entirely as an object of adoration, while the angel leads the beholder into kneeling and praying the Ave Maria. Just as in panels of the Virgin and Child, her frontality is combined with a certain detachment, which indicates that she belongs to a different reality. In such images detachment is created because the Virgin does not look at the viewer but at the Christ Child or gazes into the distance. In the Mérode Annunciation, her remoteness comes from her act of reading.

Visualized Metaphors in Honor of the Virgin

Besides expressing aloofness, the Virgin’s attention to her book may also carry a specific meaning. Medieval authors supposed that, when the angel visited her, she was reading either the Psalter or else the prophecy from Isaiah 7:14: “Behold a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son.”47 In fifteenth-century Annunciations she is always provided with one or more books as a sign of her study of the Scriptures, and often she is sitting behind or next to a lectern. The book that Mary is reading in the Mérode Annunciation, however, has an unusually conspicuous place, because she holds it in front of her breast. In view of this prominence, it may be relevant that in devotional texts the Virgin was compared to a book. In a late medieval Netherlandish litany, she is even saluted as Gegroit sys du maria, eyn boick, vol gheschreven vol genaden (Greeted art thou, Mary, a book fully written full of grace).48

We do not know, however, if such a meaning was intended here. A different one, for which there seems to be more evidence in the picture itself, can be found by relating the unusual way the Virgin is holding her book to another deviation from the Brussels Annunciation, namely the presence of the tiny Christ Child that is on his way to her womb, having entered the room—accompanied by seven rays of light symbolizing the gifts of the Holy Spirit—through one of the round windows in the side wall (fig. 10). The motif of the Christ Child or, as German art historians say, Logosknabe, flying down rays of light toward the Virgin as a symbol of the Incarnation originated in fourteenth-century Italy and spread to other countries; sometimes the figure appears, as in the Mérode Annunciation, bearing a cross.49 The image of light passing through a pane of glass was an age-old simile, favored by writers and painters, to illustrate how Mary’s virginity was left intact by the Incarnation.50 Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, for example, wrote:

Just as the brilliance of the sun fills and penetrates a glass window without damaging it, and pierces its solid form with imperceptible subtlety, neither hurting it when entering nor destroying it when emerging; thus the word of God, the splendor of the Father, entered the virgin chamber and then came forth from the closed womb.51

Rays of light shining through a window, but here with a descending dove, representing the Holy Spirit, are also depicted in Broederlam’s Annunciation (see fig. 9), in the miniatures of the same subject by the Limbourg brothers in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (ca. 1412–16; Musée Condé, Chantilly) and by the Master of the Harvard Hannibal in the Parisian book of hours (see fig. 8), and in Jan van Eyck’s Annunciation in Washington (fig. 11). In the Mérode Annunciation, these rays seem to produce the striking light effects on the lower part of the Virgin’s body, which is turned somewhat to the left, whereas the descending Christ Child can be linked to the book she is holding, with the chemise hanging just above her womb. For both the Christ Child and the book, the term “word of God” applies, with the difference that the Logosknabe symbolizes how “the Word was made flesh” (John 1:14), or, to use Saint Bernard’s description, how the word of God entered the virgin chamber.

Does it go too far to see an analogy between the elaborately represented chemise of the book and the cloth in which the Virgin holds the naked Christ Child in Marian images? This question is justified by The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen (see fig. 7), from the Master of Flémalle group.52 In this panel, too, the Virgin is sitting in a domestic interior before a bench positioned in front of a fireplace; the Christ Child lies on a cloth on her lap, and a book with a chemise binding is emphatically represented next to her, on a pillow on the bench. The Christ Child and the book mirror each other in an intriguing way, which may indicate a symbolic connection.53

The proposed relationship between the book held by the Mérode Virgin and the descending Logosknabe can be doubted because such a Christ Child is absent in the Prado Annunciation (see fig. 6). There, the Virgin holds her book in a similar way but, instead of the Christ Child, God the Father is represented, surrounded by angels and sending down rays of light. Since Gabriel has not yet entered the church interior in which the Virgin is dwelling, her act of reading seems more natural than in the Mérode Annunciation; this has been put forward as an argument for the idea that she was invented for this composition,54 with the implication that the painter of the Mérode Annunciation borrowed a figure without caring about its suitability for the scene. The peculiarity of the reading Mérode Virgin, however, who has a more confrontational character than the Prado Virgin because of her monumentality within the setting, gives every reason to see her as the result of a deliberate choice. The same motif could very well have been used in the Prado Annunciation without its original symbolic meaning but as an element that—together with the elaborate architecture, the angel arriving in the open air, and God the Father looking down from heaven—fits the narrative character of the image.

Even if the Logosknabe in the Mérode Annunciation is not directly associated with the book, it contributes to the glorification of Mary’s role in the Incarnation and reinforces the image’s connection to the Ave Maria, in which both the Virgin and the fruit of her womb are blessed. Additional rhyming prayers in the vernacular, incorporating or paraphrasing the Ave Maria, may also have been a source of inspiration for the painting. If we limit ourselves to Netherlandish examples—the patron may also have been a French or German speaker—the Ave Moeder van genaden (Hail Mother Full of Grace), written around 1400 in Bruges, offers compelling parallels.55 Saluting the Virgin plays a great part in this prayer; the first fifteen verses begin with “Ave.” Throughout the prayer, Mary is praised with the help of numerous metaphors; she is called, among other things oetmoedicghe doctrine (humble doctrine), lelye reyn van bladen (lily with pure petals), der zuverheiden scrine (shrine of purities), fonteine daer wi in baden (fountain in which we are bathing), and rose vul van shemels dauwe (rose full of heavenly dew). The last part of the prayer pays honor to die vrucht van dinen lechame reyne (the fruit of thy pure body) and contains the supplication lech up mi dinen mantel wijt (lay upon me thy wide mantle).

This supplication shows how being covered with the Virgin’s mantle was not only a question of collective protection—as visualized by the iconographic theme of the Madonna della Misericordia or Schutzmantel Madonna, which also occurs in the Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck and his workshop in New York (ca. 1440–41; Metropolitan Museum of Art)—but also of individual devotion. In the Mérode Annunciation, Mary’s mantle, loosely draped around her on one side, with a large part of it spaciously falling down from the bench, lends itself well to evoke a wish to be embraced within the Virgin’s cloak, but it may be too far a leap to assume a correspondence here between prayer and image (fig. 12). The same is not true for other metaphors used in the prayer and motifs in the panel. The expression oetmoedicghe doctrine accords with the Virgin’s position as a Madonna of Humility, and the phrase rose vul van shemels dauwe is reflected in the color of her robe and mantle, which are, in contrast to the Brussels panel and other Annunciations, both red.56 The panel contains an allusion to the Virgin as a lelye reyn van bladen, since a branch with lilies is a fixed attribute of Annunciations; the idea of the Virgin as der zuverheiden scrine is symbolized by the rays of light passing through a window (see fig. 10) and by the niche with a laver and basin, and, next to it, a towel. Such niches existed in contemporary reality, both in domestic and ecclesiastical settings.57 Here it replaces, as a visually richer element but with a similar meaning of symbolizing Mary’s purity, the brush in the Brussels work. The motif of a laver and basin, which can also be seen in the Annunciation of Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432; St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent) and an Annunciation from the workshop of Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1435–40; Musée du Louvre), has been described by Panofsky as “an indoors substitute for the ‘fountain of gardens’ and ‘well of living waters’ from the Song of Songs.”58 Thus, it corresponds with the fonteine daer wi in baden of the prayer.

The Ave Moeder van genaden demonstrates how metaphors in honor of the Virgin played a part in prayer practice, and it confirms that not only the frontally depicted, reading Mary but also other aspects in which the Mérode Annunciation differs from its model can be explained by the wish of the patron to optimize the panel’s function as an accompaniment to prayers. In my opinion, this makes it problematic to relate the image to the Eucharist by attributing all kinds of liturgical meanings to its motifs. Because the panel was made as an autonomous work, there is also no reason to interpret it as part of an elaborate, preconceived symbolic program that would include all three panels.59

Symbolic or Non-Symbolic?

The research into the symbolism of the Mérode Altarpiece (fig. 1a) has its own complex history, independent of stylistic analysis. Scholars, especially those stimulated by Panofsky’s theory of disguised symbolism, have gone to great lengths to detect symbolic allusions in the painting,60 but at some point these activities met with skepticism,61 and today there is no consensus about the extent to which the work should be interpreted symbolically. Although, as has been demonstrated here, symbolism plays an unmistakable role in the Annunciation panel, this does not necessarily imply that each element was intended to carry a deeper meaning. It is beyond the scope of this article to pay attention to all the motifs that have been discussed in the past; I will focus on one in order to explore the question of whether the symbolic and non-symbolic could have been combined in the image. This motif is the smoking candle on the table.

In the Brussels Annunciation a candleholder with two arms, one of which contains a half-burned candle (fig. 13), stands on the table; in the Mérode Annunciation this object has been changed into a candlestick with a candle that, in view of the smoke swirling upward, has just been blown out (fig. 14). Regarding the motif in the Mérode panel, Panofsky refers to a medieval hymn in which the Virgin is characterized as a candleholder and her son as a lighted candle. Here, this symbolism is superseded, he thinks, by an association with Saint Bridget’s well-known vision of the Nativity, which revealed to her how the earthly light of Saint Joseph’s candle was “reduced to nothingness” by the divine light.62 In accordance with this vision, the Nativity in Dijon shows Saint Joseph holding a candle in one hand and shielding it with the other from the light rays emanating from the Christ Child. If we assume that the Mérode candle has been extinguished by the light rays entering the room together with the Christ Child, the problem arises about how to interpret the corresponding candle in the Brussels Annunciation, since there are no such rays, and there is no sign that the candle was burning just before.63 To find an explanation that takes account of both candles, we must look at candles in other Annunciations and Madonna panels.

In a small panel known as The Virgin and Child in an Interior (fig. 15) in London, presumably made by Jacques Daret,64 a candle in a sconce attached to the fireplace is burning in full daylight. A symbolic meaning seems obvious and can be found in the hymn that praises the Virgin and her son as candleholder and lighted candle.65 In the Annunciation by Broederlam (see fig. 9) and an Annunciation (fig. 16) by Hans Memling in New York, the Virgin holds a lighted rope candle, consisting of a ball of waxed flax.66 In the underdrawing of the latter painting, instead of the rope candle, the contours of a candlestick with a candle are visible above Mary’s hand. During the execution process, the artist must have decided, or been ordered by the patron, to represent the Virgin herself as the holder of the candle that symbolizes Christ; as in the Broederlam panel, a rope candle, held in the palm of her hand, seemed most appropriate for this idea.

In Memling’s Annunciation with Angels (fig. 17), also in New York, an unlighted rope candle and an empty candlestick both appear in the background on a cupboard, next to a small carafe, which in this and other paintings is generally regarded as a symbol of the Virgin’s purity.67 Like the motif of the windowpane, the carafe refers to her as glass through which rays of light can pass without breaking it. It seems probable that the rope candle and candlestick also have symbolic meanings, but their combination is awkward, as is the fact that they do not support a light, as if the Incarnation has yet to take place. This idea is contradicted by the dove in a halo descending upon the Virgin.

A dove above the Virgin’s head and an empty candlestick behind her were earlier depicted in the Annunciation of the Ghent Altarpiece. Should this be understood as indicating different moments—the angel’s salutation and Christ’s entering the Virgin’s womb—shown together in one representation? An empty candlestick, however, is also present in Van Eyck’s Lucca Madonna (ca. 1437; Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main), where in a niche next to the enthroned Virgin and Child it joins other objects that are seen in the Annunciation of the Ghent Altarpiece—namely a carafe and a basin. Strange though it may seem, apparently even an unlighted (rope) candle and an empty candlestick could refer to the Incarnation.

In both the Brussels and the Mérode Annunciations (figs. 18 and 19), two candleholders, one with an unlighted candle, the other empty, are attached to the fireplace. In the Brussels panel they flank the woodcut with Saint Christopher carrying the Christ Child and therefore, just like the image, may be considered as alluding to the Virgin bearing Christ68—except that the candle has already been used, in view of its black wick and dripping wax. A similar difficulty presents itself with respect to the Brussels candleholder on the table; although the two arms might prompt inventive iconologists to ponder the two natures of Christ, the half-burned candle defies such a possibility. It seems most likely that the three candleholders in this painting are just domestic attributes, with the one on the table probably testifying to the Virgin’s intensive reading of the Scriptures.

The impossibility of finding a common denominator for the candles and candleholders in the various pictures justifies the suspicion that painters using these motifs had a free attitude toward their meanings, so that they could apply them less strictly and even without any symbolic intention. How this freedom could lead to a mixture of symbolic and non-symbolic motifs in one image is illustrated by The Virgin and Child in an Interior ascribed to Jacques Daret (see fig. 15). Besides the lighted candle, a deeper meaning may be attributed to the Christ Child touching his penis while kissing the Virgin on the lips and fondling her chin—although, in my opinion, this symbolism does not reach so far that it would pertain, as is supposed, to the Circumcision and/or the Bridegroom and Bride from the Song of Songs.69 The attention the Christ Child draws to his penis can be interpreted to underline his human nature, like the exposure of his genitals in The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen (see fig. 7); The Virgin and Child with Saints in the Enclosed Garden in Washington (ca. 1440–60; National Gallery of Art ), also from the Master of Flémalle group, and The Virgin and Child with Saints and Canon Joris van der Paele by Jan van Eyck, in Bruges (1436; Groeningemuseum).70 The motif of the caress, derived from Byzantine art, may just be taken as expressing the tender relationship between the Virgin and the Christ Child.71 Other elements in the image reflect a transformation from the symbolic into the non-symbolic. The Virgin is sitting on a cushion, on the footstool of her bench, as in the Brussels and Mérode Annunciations, but the symbolism of the Madonna of Humility is toned down for a good, practical reason, as is evident from the objects on either side of her. One is a basin filled with water, similar to the basins in the Annunciation of the Ghent Altarpiece and the Lucca Madonna, where they symbolize Mary’s purity; the other is an ordinary wicker basket with baby clothing.72 Together, they make clear that the Virgin is simply going to wash and change the infant Jesus, which explains not only her position but also why she has thrown off and hung up her mantle on a rail, just as the farmers in the February miniature of the Très Riches Heures have hung up their clothes.73 The rail in The Virgin and Child in an Interior, with its special construction for attaching it to the wall, is also pictured in the right wing of the Werl Altarpiece, with Saint Barbara (1438; Museo del Prado), from the Master of Flémalle group, but on that rail a towel is hung above a laver and basin, symbolizing the purity of the Virgin, who was surely represented in the lost center panel. A towel also hangs from a rail above a laver and basin in The Virgin and Child by a Fireplace in the Hermitage (dating uncertain), from the Master of Flémalle group.74 The mantle on the rail in The Virgin and Child in an Interior does not seem to have any symbolic meaning and corroborates the idea that the painting was especially intended to stimulate the empathy of the beholder and to inspire delight in the domestic, maternal depiction of mother and child.

The Virgin and Child in an Interior and the Mérode Annunciation mirror each other in the sense that, in the first work, an iconic theme is given a narrative character, and in the second, a narrative scene has acquired an iconic character. They also mirror each other in the use of symbolic and non-symbolic elements. In the first image, the symbolism of Mary sitting on the ground is superseded by the fact that she is taking care of the Christ Child; in the Mérode Annunciation, this symbolism is emphasized by the iconic appearance of the Virgin. On the other hand, in The Virgin and Child in an Interior, the lighted candle seems to have a symbolic meaning—referring, like the Christ Child touching his penis, to the Incarnation—whereas in the Mérode Annunciation, the smoking candle appears to have only a narrative function.

The latter assumption can be defended not only because of the difficulty of finding a satisfying symbolic explanation for this motif but also because of the fluttering pages of the book on the table. Fluttering book pages also occur in the Brussels Annunciation (fig. 20) and may suggest the sudden entrance of the angel, who according to the Meditationes, “flew down from heaven and in a minute stood in human form before the Virgin.”75 In The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen (see fig. 7), however, there seems to be no reason for the fluttering book page other than creating a counterpart to the liveliness of the Child. At the same time, we need to realize that fluttering things must not have been uncommon in rooms like the one depicted in this image, with an unglazed window through which a gust of wind easily could enter. Apart from the question of whether the book pages in the two Annunciations—and also the smoking candle and the scroll, with one end curling up, in the Mérode panel—should be connected to the appearance of the angel76 or to the partly unglazed windows, they are all suggestive elements in the composition. In the Brussels panel, the pages emphasize the interaction between the two figures. In the Mérode Annunciation, the candle, book, and scroll (fig. 21) provide an expressive contrast to the immobile Virgin. Here, the book, with two fluttering pages, and the candlestick, with one holder, are somewhat simplified in comparison with the Brussels Annunciation, but they are placed closer to the front; moreover, the book is clearly defined against the green storage bag. The candle is meticulously painted with its glowing wick and wisp of smoke becoming thinner and thinner.

All the motifs in which the Mérode Annunciation differs from the Brussels panel, whether they have symbolic or non-symbolic meanings, offered its painter the opportunity to display his taste and skill. This is especially visible where he deviates subtly from his model. Omitting the woodcut with Saint Christopher on the fireplace, possibly at the wish of the patron, he transformed the sculpted heads of a man and a woman decorating the corbels of the fireplace into full figures. The two wood-carved pairs of a lion and dog on the farthest ends of the bench, standing with their backs to each other, were turned around.77 The mechanism for the reversible back of the bench—a piece of furniture called wendlys or keerlys, also represented in the Annunciation by the Master of Hannibal in the Parisian book of hours—is attached lower on the inside of the arms.78 On the table, the pitcher, a specimen of Florentine maiolica imported into the Low Countries, was turned slightly, so that only a very small part of the bird decorating it was left to accentuate the object’s volume, perhaps because an association with the dove of the Holy Spirit was considered unsuitable. The side of the pitcher, on the other hand, was embellished by replacing the band with Xs from the Brussels pitcher with a mixture of pseudo-Hebrew and pseudo-Greek letters.79 The use of these letters may be an allusion to the languages of the Old and New Testaments and, therefore, to the fulfillment of the prophecies through the Incarnation.80 Although the inscription is a product of invention, the real pitcher that served as a model for the Brussels Annunciation seems to have been reused to represent it from a different angle.81 Thus, the artist studied reality not only when introducing new objects into the painting—such as the laver and the candlestick, which like the maiolica pitcher are quite similar to preserved examples82—but also when making alterations to objects previously rendered in the Brussels panel. Transforming the Brussels candle into a smoking one must have been a specific challenge for his interest in realistic representation.

The Wings

Whereas both the frontal position of the Virgin and the symbolism in the Mérode Annunciation can be explained by the panel’s initial function as a visual accompaniment for praying to the Virgin, the iconography of the wings suggests that when these were added, the painting acquired a new function. In the left wing (fig. 4a), the donor, kneeling at the open door of Mary’s house, expresses his wish to join the angel in the salutation and adoration of the Virgin. The rosebud pinned on his hat and the rosebush growing against the wall behind him may relate to the metaphor of the Virgin as a rose, visualized in the Annunciation by her completely red clothes,83 but the rose was also used as a metaphor for the Ave Maria prayer. Long before the official introduction of the rosary in the second half of the fifteenth century, the praying of a fixed number of Ave Marias was described in Middle-Dutch with terms like rozenkrans, rozenhoed or rosarium.84 For this reason, the rosebud and rosebush may symbolize how the donor devotes himself to praying the Ave Maria.

This allusion corresponds with the theme of the center panel—yet there is a discrepancy between the two panels. The addition of the donor portrait does not harmonize with the frontality of the Virgin; it would have been more appropriate if she turned to the left, as in the Brussels Annunciation. Apparently, the Annunciation no longer served only as an accompaniment of a personal prayer practice. True, the depiction of the donor kneeling at the Virgin’s door may have been a stimulus for imagining how he could enter her house in the spirit, but apart from this, seeing his own portrait each time he prayed must have made little sense.85 It can be supposed that when the Annunciation was expanded with wings, including the portrait of a donor, it received a new function as an altarpiece. Besides accompanying the donor’s devotions, the work became an act of devotion itself by manifesting his devotional intentions.

The right wing (fig. 3a) also shows a discrepancy in relation to the center panel, here concerning the remarkable symbolic motifs used for representing Saint Joseph in his workshop. The combination of this subject with the central image can be explained by an apocryphal tradition, according to which the Virgin was already living with Saint Joseph when she was visited by the angel.86 Although there are earlier examples in French and Spanish art of Saint Joseph as a carpenter at the Annunciation,87 Meyer Schapiro, in a famous article from 1945, related his presence in the Mérode Altarpiece to a growing cult of this saint in the Low Countries; Joseph was praised as an artisan and venerated as the chaste husband of the Virgin.88 In the latter role, he was “the guardian of the mystery of the incarnation and one of the main figures in the divine plot to deceive the devil.”89 This idea is of crucial importance for the central theme of Schapiro’s publication: the mousetraps, depicted on Joseph’s workbench and on the lower window shutter, which is put down to serve as a display shelf for the people in the street (fig. 22). Earlier than Schapiro, Johan Huizinga detected the symbolic meaning of the Mérode mousetraps, referring to the twelfth-century theologian Peter Lombard, but this has long remained unnoticed.90 Independently, Schapiro found the original source for the motif in the sermons of Saint Augustine, who, among other things, wrote: “The devil exulted when Christ died, but by this very death of Christ the devil is vanquished, as if he had swallowed the bait in the mousetrap. . . . The cross of the Lord was the devil’s mousetrap; the bait by which he was caught was the Lord’s death.”91

By representing Joseph as a maker of mousetraps, his reputations as both an artisan and a deceiver of the devil, because of his marriage to the Virgin, are ingeniously combined. As a metaphor for Christ’s cross, the mousetrap complements the symbolism of the descending Christ Child in the center panel, who carries a cross to signify the purpose of the Incarnation. There must have been, however, still another reason why the devil received special attention in this side panel, because, as Charles Minott has discovered, the image contains more objects alluding to him: the ax, saw, and rod that are conspicuously presented in the foreground, and the brace and bit that Joseph is handling.92 The first three objects are mentioned together in Isaiah 10:15: “Shall the ax boast itself against him that cutteth with it? Or shall the saw exalt itself against him by whom it is drawn? As if a rod should lift itself up against him that lifteth it up, and a staff exalt itself, which is but wood.” According to a commentary by Saint Jerome, these words, directed to an Assyrian king, can be applied to “the arrogance of heretics and to the Devil, who is called the ax, the saw, and the rod in the scriptures, because through him unfruitful trees are to be cut down and split with the ax, and the stubbornness of the unbelievers sawn through, and those who do not accept discipline are beaten with the rod.”93

The brace and bit have a similar meaning, as indicated by the Targum of Isaiah, an interpretative translation of Isaiah in Aramaic, in which the ax is replaced with an auger: “Is it possible that the auger shall boast over him who drills with it, saying ‘Did not I drill?’”94 A derivation from this source is intriguing, since knowledge of Targum texts among Christians was rare during the Middle Ages.95 Nevertheless, the presence of ax, saw, rod, and brace and bit fits too well with the two texts from Isaiah to deny a connection.96

The board Joseph is drilling has been the object of an extensive and still-unresolved debate among scholars (see fig. 3). Various authors have suggested that the saint is making a foot stove, with no symbolic allusion; a spike-block, as an instrument of the Passion; a baitbox, as another trap for the devil; a firescreen, as a barrier against the devil or as a sign of Joseph’s chastity; a mousetrap (in which scenario the identified mousetraps would be planes); a holder for the rods of the Virgin’s suitors; or a strainer for a vinepress, as a reference to the Mystic Vinepress, which is a metaphor for Christ’s sacrifice.97 The difficulty of identifying the object could be an indication that it has no specific, symbolic meaning and only serves to illustrate Joseph’s use of the brace and bit.

Recently, Malcolm Russell has tried to demonstrate that the carpenter’s tools lying on the workbench are instruments of the Passion.98 However, relating the chopping knife to the breaking of the legs of the two thieves who were crucified together with Christ does not make it one of the arma Christi, and there is little reason to identify the small wooden bowl containing some nails as the chalice in which Christ’s blood was collected. Moreover, I find it difficult to see in the arrangements of the tools allusions to the three crosses of Calvary and rather think that they are placed in this way to enhance the sense of depth.99 It is quite imaginable that the panel contains more symbolism than has been noted here, but it can be assumed that, as in the Annunciation, symbolic motifs are combined with non-symbolic ones.

The motifs that leave little doubt about their symbolic meanings indicate the participation of a learned theological advisor who invented a way to represent God’s power over the devil. The painter has given this shape not only by depicting these motifs but also by their compositional ordering. First, Joseph’s drilling catches the eye, which should be understood, together with the ax, saw, and rod in front of him, as signifying that the devil has no real power, because he is just a tool in God’s hand. Looking deeper into the scene, one notices the mousetraps, which have an even stronger message, namely that Christ has slain the devil. It is remarkable that the most prominent symbolic objects, held by Joseph and lying at his feet, do not pertain to Christ’s Incarnation and Passion; nor do they, according to Saint Jerome’s exegesis, specifically refer to the Old Covenant, in which case they could be indirect allusions to the Incarnation. Since their meaning—that God employs the devil to destroy unproductive, unbelieving, and undisciplined people—stands apart from the content of the center panel, it must have had a very special reason. The original and peculiar symbolism of the Joseph panel, going beyond the main theme of the triptych, gives rise to the assumption of an important, maybe even dramatic occurrence in the life of the patron depicted in the left wing. This event may have made him realize or hope—if a favorable outcome was not yet certain—that the devil, instead of doing him harm, was used by God to punish one or more of his enemies.

A preoccupation with the devil may have generated the decision to transform the Annunciation into a work with a different purpose. In contrast to the symbolism in the center panel, the motifs in the right wing cannot be related to an established prayer practice; they support the idea that the donor had vowed, or at least decided, to dedicate the painting to the Virgin because of her intercession for God’s help in a distressing personal situation. Jozef De Coo has proposed, on other grounds, that the Mérode Altarpiece is a votive picture; he explains the combination of the portrayed couple and the Annunciation by either their wish or their gratitude for having a child.100 Since the wife was only added at a later stage, it is hard to imagine that this theme played a part when the wings were ordered. There is more reason to see the portrait of the donor, together with the remarkable symbolism of the right wing, as testifying to his faith in God’s protection against evil forces. The three panels together may have been intended to express his supplication or thanks to the Mother of God for her intercession.

It is likely that the donor had the portrait of his wife painted on the occasion of their marriage (fig. 4b). Holding a string of precious coral prayer beads, she joins him in his prayers to the Virgin. With a tiny golden pendant representing the figure of Saint Christopher attached to these beads, a motif from the Brussels Annunciation reappears; here it could be a sign of protection or even allude to the wish of bearing a child.101 The figure of the man in the background of the panel, who was probably added at the same time as the donor’s wife, has been identified—on the grounds of the small shield he bears on his breast—as a messenger in the service of the city of Mechelen.102 His presence implies that the portrayed couple lived there. Standing next to the gate with its half-open door, which offers a view onto a city center, he finds himself in the transitional space between the enclosed garden, from which the donor and his wife address the Virgin, and the public life outside its walls. Just like the donor, the messenger holds his hat in his hand as a token that he too, albeit at a respectful distance, salutes the Virgin. In this way, the image suggests that other citizens of Mechelen, represented by this official, follow the couple in their adoration of the Virgin. By including the community to which they belonged in their devotion, the donor and his wife must have wished to impress their fellow citizens with an altarpiece, installed in a church or chapel in Mechelen, that showed how they gained access to a higher reality.103

The need for prestige manifested itself not only in such a devotional ambition but also in the impression the triptych was intended to make as a virtuosic painting. Even if the wings were not made by the painter of the Annunciation, they too demonstrate great artistic skill, with a similar love for detail and texture. In the left wing, the wall of the garden forms a secluded background for the portraits but also offers a glimpse through the gate into the town. This image can be admired for its precision in rendering the vegetation; the silver ornaments on the dagger and purse of the donor; the prayer beads of his wife; the fur lining of her robe; and the ironwork on the door of the Virgin’s house. The right wing, in which the carpentry workshop has less depth than the Virgin’s room but opens into a cityscape vista, astonishes because of the way the painter has indulged in representing the workshop, with its variety of utensils, and the marketplace with its charming details.

The amazement that the Joseph panel was meant to evoke must also have included its symbolism. Although the idea of representing God’s power over the devil can be explained by the devotional purpose of the painting, the erudite character of the symbolism suggests that the donor also wished to give his altarpiece an elite, intellectual aspect. He evidently asked a theologian to invent motifs whose meanings were impossible to grasp without knowledge of the various texts on which they were based. Such a knowledge was uncommon, and it may have had a special attraction for the donor to disclose those meanings to others, according to the triptych’s function—confirmed by the presence of the messenger in the background—as a prestigious, semipublic, devotional object.

Conclusion

Although the Mérode Altarpiece is no longer valued as a key work in an artistic oeuvre and in the history of painting, it has lost none of its importance. Connoisseurship is a necessary method for studying the painting, but, like technical and iconological research, it is not suited to determine fully the work’s significance as an artistic, historical object. This significance is best understood, as I have tried to show, by tracing how elements of form, content, and function relate to each other. These connections can be recognized in the center panel by regarding it as originally an autonomous painting and a product of careful choices that made it deviate considerably from its model. When the Annunciation was combined with side panels, its initial form and content were connected to a new function, given expression by the form and content of the new images. The internal discrepancies that result from the development of the triptych in various stages make it a complex but fascinating document of devotional, artistic, and social intentions.