The unprecedented inclusion of a Black maidservant in Rembrandt’s The Visitation invokes the global reach of the new faith as expressed at the dawn of Christianity in the Gospel of Luke (1:39–56) and later reiterated by Erasmus and Jacobus Revius. The woman’s African features and attire would have resonated with Dutch merchants around 1640, when the West India Company fully embarked on trade in enslaved people in Africa and the Atlantic. The maidservant raises moral, religious, and sociocultural questions concerning attitudes toward colonialism and enslavement that may have influenced Rembrandt and informed contemporary reception of the painting. By offering three hypothetical identities for the anonymous but presumably living model—either an enslaved or free woman from Rembrandt’s neighborhood in Amsterdam—this essay joins a wave of scholarship that employs contextual evidence to redress the erasure of Black people from the historical record.

Recent research has raised new awareness of the Black presence in Dutch art, especially in relation to the wider context of colonialism, race, and trade in enslaved people.1 Elmer Kolfin, a major contributor to the field of Black studies in Netherlandish art, justly laments that visual images of Africans have been relegated to the “shadows” by artists, art historians, and curators alike.2 His publications, and those of Mark Ponte, David de Witt, and Carl Haarnack with Dienke Hondius, among others, have established an approach based on context to investigate images of Blacks in early modern history.3 Rembrandt (1606–1669) merits special attention in this regard, for he stands out among his Dutch contemporaries for his production of at least twelve paintings, eight etchings, and six drawings in which Black people play roles as spectators or participants in biblical scenes.4

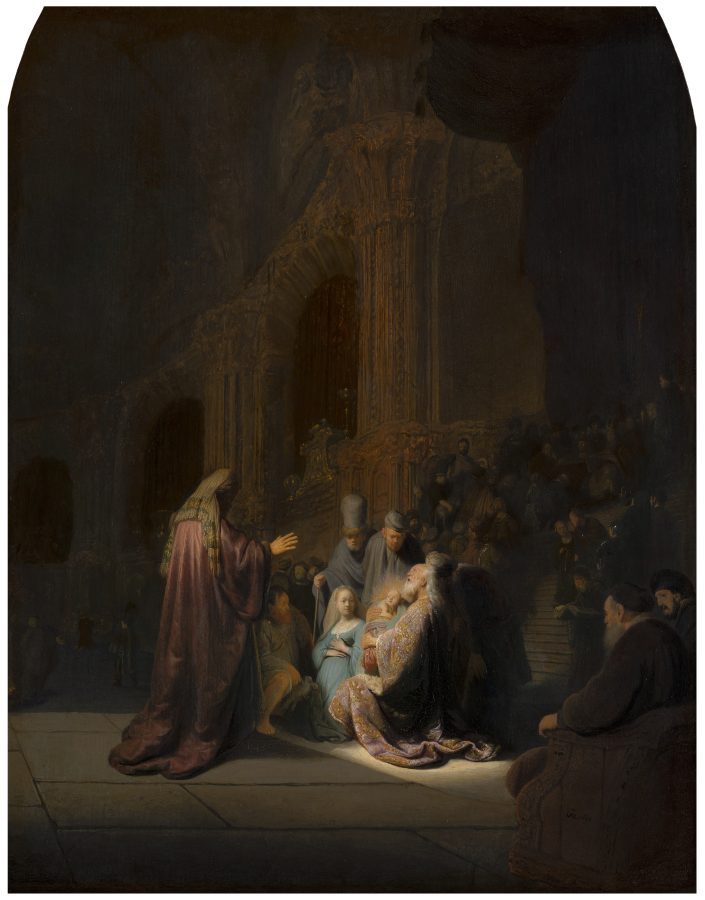

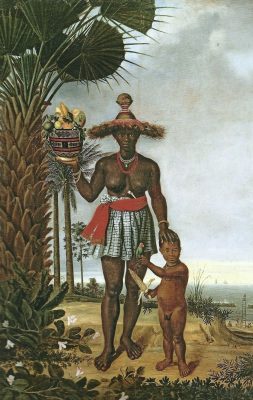

This study of The Visitation of 1640 (fig. 1) focuses on Rembrandt’s unprecedented—indeed, unique in the history of art—insertion of an African woman into the meeting between Mary, newly pregnant with Christ, and her cousin Elizabeth, pregnant in her old age with John the Baptist (fig. 2).

Although the biblical text, Luke 1:39–56, does not mention a servant, Rembrandt places the African woman near the very center of the painting, standing close to the two holy women on the same rounded step, where she dutifully removes Mary’s cloak to reveal the Virgin’s miraculous pregnancy. Rembrandt’s inventive approach to the Visitation has religious as well as sociopolitical implications.5 The artist, who exhibited a lifelong interest in bringing Bible narratives down to earth, into his own world, would have been aware of the religious implications of inserting into the painting a Black figure, whose presence also connoted contemporary issues of colonialism.6

Comparisons with Dürer’s woodcut of the same subject, and with images of Black people in other works of art by Rembrandt and Jan Lievens, reveal what is distinctive about the maidservant in The Visitation. Her features are naturalistic, and her distant place of origin is invoked by the striped fabric of her clothing, which associates her with both West Africa and Brazil. Her appearance and dress convey the global reach of Christianity, and her placement near the holy women suggests her inclusivity within the new faith, as she ponders her own conversion (fig. 3). The religious import of her presence is revealed by analyzing the biblical source text and commentaries by Erasmus and John Calvin.

The Visitation is a pivotal moment in the transition between the Old and New Testaments, which Rembrandt emphasizes in his painting through the figures of Joseph and Zacharias, the women’s husbands; the architecture of Zacharias and Elizabeth’s home; the topographical view of the Jerusalem Temple in the background; and the subtle variations in light, only partially illuminating the servant as she contemplates the Christian message. Rembrandt’s use of light in The Visitation, as we will see, may have been inspired by Jacobus Revius’s poem “Mary,” published in 1630.

This essay explores the extent to which the maidservant’s African appearance would have invoked ethical, religious, and sociopolitical issues surrounding colonialism and the slave trade in the years around 1640, when the Dutch West India Company (WIC) fully embarked on human trafficking to supply labor for sugar plantations and mills in the colonies. Some Dutch contemporaries may have been shocked to see an African servant intimately engaged with the holy figures in The Visitation but were probably mollified by her reverent facial expression, which could suggest the possibility of conversion. Such prominent Calvinists as Willem Usselincx, Godefridus Udemans, and Johannes de Laet, who sought to convert Indigenous people and Africans to the Reformed faith, would have appreciated her appearance in this painting as an acknowledgment of their mission.

The young woman attending Mary in Rembrandt’s The Visitation was probably inspired by someone residing in his neighborhood around the Breestraat, later known as Jodenbreestraat (Jewish Broad Street), where Sephardic merchants and others brought enslaved Africans home from the colonies to serve as domestics in their households. Black residents of this neighborhood may have worked as models for Lievens and Rembrandt.7 The maidservant in The Visitation appears to be based on a real person, whether engaged formally or informally as a model or simply observed in the street (see fig. 2).

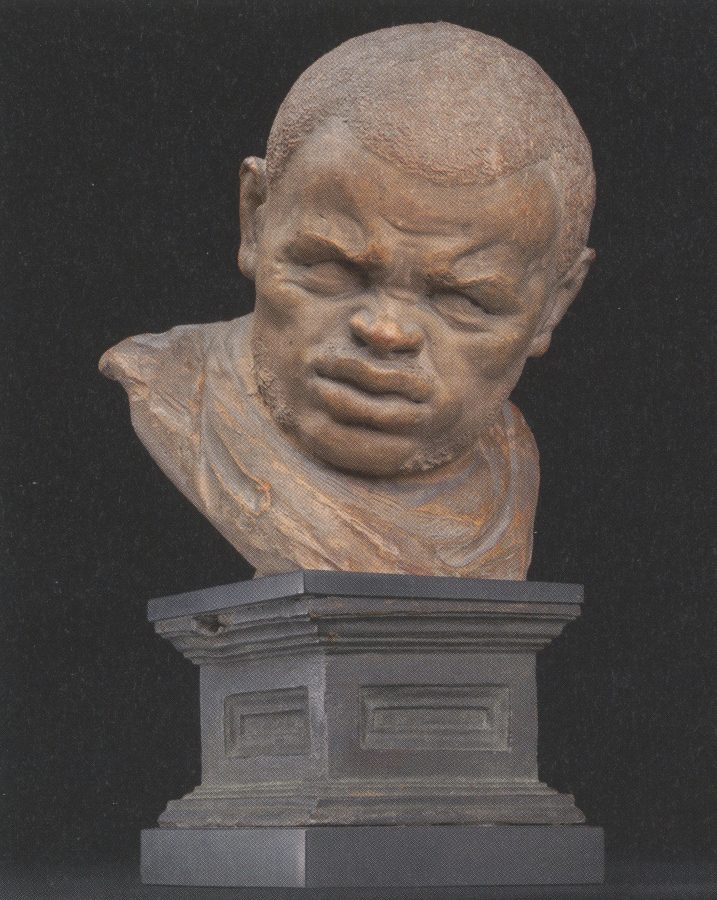

In contrast, the woman in Rembrandt’s earlier etched Bust of an African Woman of about 1631 presents as a stereotype of a Black person (fig. 4). This tronie may have been based on a sculpted bust of an African man in the collection of Jacques de Gheyn III (fig. 5).8 Indeed, the woman’s exaggerated features, especially the prominence of her forehead and lips and the flatness of her nose, repeat the racial caricaturing of the sculpture. Unlike the painted servant, the etched African woman is tense, anxious, and distrustful, with her unfocused eyes narrowed to slits. Her features and gaze suggest a later statement by the art theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), who worked as a student in Rembrandt’s studio from about 1642 to 1648. Intoning Philostratus, Van Hoogstraten writes:

A drawing without color [can] indicate sufficiently the form of a black or white human figure. Such that a Moor, even if drawn in white, will appear black because of his flat nose, short hair, fat cheeks and a certain stupidity in the eyes, all of which easily express to the knowledgeable viewer that this is a black person.9

Van Hoogstraten’s statement about “stupidity in the eyes” (zekere dommicheit ontrent zijn oogen) may have been a common stereotype for Black immigrants newly arrived in Rembrandt’s Amsterdam. But the peaceful and hopeful face of the servant in The Visitation is intrinsically connected to the role she plays in the biblical narrative staged by the artist (see figs. 1, 2 , and 3).

The sociopolitical context for the painting gains currency in this essay’s formulation of three alternative profiles—as either an enslaved or a free woman—for Rembrandt’s anonymous model. Drawing on historical evidence published by Mark Ponte, Lydia Hagoort, and others, the model’s imagined identities remain hypothetical, but their theoretical nature is consonant with a recent scholarly openness to speculation that has been embraced across many disciplines as a way of overcoming the silence or bias of the historical record.10 While useful to scholars, recently published statistics on the numbers of enslaved people in the colonies can nevertheless be viewed as commodifying them, just as the slave traders once did.11 The plausible profiles presented here provide an opportunity for the model to emerge as more than a cipher in a mass of statistics. Most likely one of several Black people documented as residing in Rembrandt’s neighborhood, she is here assigned a fictive Iberian name, Hester da Silva, to give her the historical presence she had been denied. Thus, she reclaims her erased identity as, in the most likely scenarios, either an Afro-Portuguese Creole born in Guinea, sold to Brazil and brought to Amsterdam to work in a Sephardic home; a freeborn Afro-Jewish member of a Sephardic household; or a free woman living independently in Amsterdam.12

Hester da Silva’s tentative biographical sketches chiefly focus on her life in Rembrandt’s neighborhood, where she is imagined as living in a Sephardic merchant’s household. The social history of the Sephardim—a persecuted minority in Spain and Portugal, considered racially Black by Iberians and other contemporaries—may offer insights on their relationships with domestic servants like Da Silva. While her life as a Black woman, enslaved or free, would have been complicated and challenging, Rembrandt’s rendering of her as the African servant in The Visitation engenders a Christian ideal that is the all-encompassing theme of the painting—the universality of the new faith.

The Dawn of a New Covenant and the African Servant

Throughout his career, Rembrandt engaged with religious narratives dealing with God’s covenant with humanity. Many of his Old Testament subjects are concerned with God’s promises to Israel, sustained through the suffering, setbacks, and perseverance of the Hebrews. Rembrandt’s belief in the inheritance of this ancient covenant through the incarnation of Jesus, offering salvation to humanity, is evident in his many New Testament subjects that portray the travails and joys of the Holy Family during Christ’s infancy. The Visitation neatly fits within this category, since this spiritual event constitutes the first recognition of Jesus, even while in the womb, as the promised messiah of the covenant. Yet Rembrandt, who often produced multiple works on the same biblical subject, only created a single Visitation—the painting now in the Detroit Institute of Arts (see fig. 1).

The Visitation was popular in Roman Catholic art, presumably because of its emphasis on Mary and on Elizabeth’s famous words blessing her, uttered even today by Catholics in the Hail Mary prayer of intercession. The Visitation was not commonly represented in Protestant art, although woodcuts of the subject appear in editions from 1554 and 1563 of Martin Luther’s published sermons, the Kirchen Postilla.13 Uncomfortable with Elizabeth’s words of salutation, John Calvin played down the impact of the blessing by insisting that her praise did not elevate the Virgin above Christ as “the Papists” claimed but simply acknowledged God’s free act of grace in bestowing the blessing on this humble maiden.14 Notably, Rembrandt emphasizes God’s grace in bringing the gift of redemption through his son, signified by the light and by Elizabeth directing her gaze upward, toward Mary and God in heaven (fig. 2a).

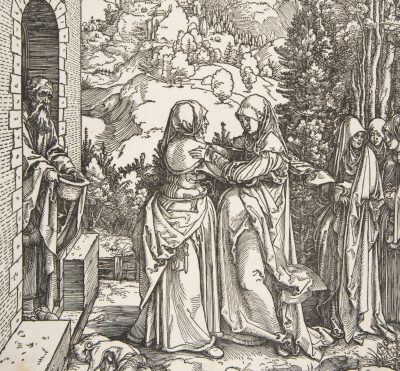

To stage The Visitation, Rembrandt drew on Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut of the subject from the Life of the Virgin, of about 1504 (fig. 6), which also situates the holy women on the threshold of Elizabeth’s home, with her husband, the lesser priest Zacharias, emerging from the doorway. Other details in Rembrandt’s interpretation are akin to Dürer’s, such as the mountainous landscape in the distance and the little dog standing at the feet of the two holy women.15 In Rembrandt’s version, however, Elizabeth, Mary, and the African woman stand together on a circular step as the other figures seem to revolve around them (see fig. 1).16 While Dürer announced his authorship by placing his monogrammed plaque, angled toward Mary, in the foreground, Rembrandt signed and dated his painting on the edge of the step beneath the holy women—implying, perhaps, not only his competition with the great German master, but also his role as witness to the event.

The most important difference between these works, however, has to do with the servant, who appears in Rembrandt’s The Visitation but not Dürer’s. The latter includes Mary’s three sisters, engaged in conversation at right, who will later witness the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. Rembrandt’s servant, not mentioned in scripture, is more than a bystander, since she participates in the religious event by removing Mary’s cloak to disclose the miraculous pregnancy.17

Certain elements in the dark background of Rembrandt’s The Visitation, especially the figure of Joseph, invoke the shadowed world of the Old Testament before the advent of Jesus (see fig. 2). To the right and below the steps, Mary’s husband dutifully leads a donkey, anticipating his future role in assisting Mary and Jesus in the flight into Egypt.18 Joseph is an outsider to the divine parenthood of Christ, yet his lineage in the House of David places him within the ancestry of Jesus and Mary as a living link to the Old Testament. As caretaker for his family, Joseph in Rembrandt’s art routinely invokes the Jews laboring under the law of the Old Testament.19 In The Visitation, the darkness engulfing Joseph is even more pronounced in the far distance, where one can barely make out a topographical view of Jerusalem, with the round structure of the Temple at the hill’s summit.

In contrast to the temple enshrouded in darkness before the advent of Christ, the house of Zacharias is bathed in a soft light. The ample doorway with its prominent column surmounted by a foliate capital recalls the fantastical temple architecture in Rembrandt’s Simeon’s Song of Praise of 1631 (fig. 7). The reunited family members at the threshold of the house in The Visitation foreshadow the gathering of believers of the Reformed church.20 Reinforcing what Christians perceived as the transition from the era of the law to the era of grace, two peahens with chicks and a large peacock in the left foreground symbolize eternal life and Christ’s Resurrection.21 The basin at the lower right may suggest the rite of baptism later instituted by Zacharias and Elizabeth’s son, the future Saint John the Baptist.

Unlike Joseph, Elizabeth’s aged husband Zacharias, leaning on the shoulder of a young blond boy, reacts with joy and walks down the steps toward the light of the new covenant that shines brightly on Mary and Elizabeth.22 Zacharias, the lesser Temple priest, had earlier been struck mute for doubting the angel Gabriel’s prophecy that he would have a son in his old age (Luke 1:15–19). The priest’s joy is multiplied as he remembers Gabriel’s earlier pronouncement that his son, named John, will be “great in the sight of the Lord” and “will turn many of the people of Israel toward God” (Luke 1:15–16). In the doorway of Dürer’s woodcut, Zacharias likewise acknowledges Jesus as the anticipated redeemer by humbly removing his hat in a traditional gesture of homage to the Christian messiah (figs. 6a, 2b).

As a strikingly novel participant in this array of figures—Mary, Elizabeth, and their sons, who initiate the new faith; Joseph, who invokes Judaism as Christianity’s foundation; and Zacharias, the lesser priest, as a prophet of the New Testament like his son John the Baptist—the African servant adds a new inflection to The Visitation. She signifies the gentiles of the world, the very focus of Saint Paul’s worldwide mission to convert pagans (see fig. 2).23

The servant in The Visitation correlates with Erasmus’s commentary on Luke 1:50 that explains how God’s mercy “shall spread abroad every way, and issue from nation to nation, unto the furthest ends of the world, and from age to age until the last day of this world.”24 The message of Christian universality also infers the fulfillment of Old Testament prophesies that the Temple would one day “be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (Isaiah 56:7). The expectation that the nonbelieving African will embrace Christianity has its origins in Psalm 68:31, which foretells that “Ethiopia [Africa] will soon stretch out her hands unto God.”25 Inspired by his teacher, Pieter Lastman, Rembrandt painted, in 1626, The Baptism of the Eunuch (Acts 8:26–40), a popular subject that focuses on an Ethiopian high chamberlain whose requested baptism is witnessed with awe by his own Black servants (fig. 8).26 With this context, the young woman attending the Virgin in Rembrandt’s The Visitation would be understood as an Ethiopian of the biblical era.

Significantly, John the Baptist was known for spreading Christ’s message of salvation to all the nations of the world. Rembrandt portrayed precisely this mission in his grisaille of about 1634, The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist, which includes numerous foreign auditors, including an Ethiopian at the left (fig. 9). Like the global figures gathered about John the Baptist, the African woman in The Visitation listens to the message of the new faith as a potential proselyte. Her participation in the revelation manifests her important role in the painting.

The significance of her presence has been overlooked by modern scholars who consider her depiction conventional—in her subservience to white people, she performs the duties of a maid.27 Yet contemporary Dutch readers of the Bible may have seen her in a different light. Notably, hundreds of verses in the Old and New Testaments refer to persons obedient to God as servants of the Lord.28 More importantly, the maid’s actions in The Visitation may have been understood to echo Mary’s own submission in the Annunciation, which occurred just prior to the Visitation. It was then that Mary declared her obedience to God, giving voice to the famous words: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord” (Luke 1:36).

The act of unveiling performed by the servant in The Visitation was anticipated by Rembrandt’s close colleague, Jan Lievens, whose etching The Raising of Lazarus of 1630 also includes a Black maid assisting at a sacred event (fig. 10).29 In Lievens’s etching, the African woman pulls off the voluminous shroud to reveal the miracle of Lazarus rising from death (John 11).30 Rembrandt’s servant in The Visitation, however, is physically close to Mary, whereas the maid in Lievens’s print is distant from the Christian savior and shown in profile, rendering her emotionally distant from the observer. Rembrandt’s servant, in contrast, gazes outward, revealing her tender facial expression. While Lievens’s maid is elegant in her low-cut European dress, the woman attending Mary is modestly attired, wrapped in African cloth, evoking her foreign, distant origins (fig. 2c).

Subtle lighting effects are employed in The Visitation to differentiate the varied roles played by the figures. In the background, Joseph and the Temple reside in darkness before the advent of Christ; Zacharias, the prophet of Jesus, is infused with soft light; but the strongest luminosity falls on Mary and Elizabeth. Significantly, the light reflected from the mother of Christ shines on the servant, bringing her out of the shadows. Most importantly, the morning sunrise in the painting recalls Revius’s poem, published in 1630, entitled “Mary.” The first four lines of the poem are especially relevant to this comparison:

Most blessed is this maid, all virgins’ crown,

The Temple of God’s Son and inmost might,

The dawn through which the long-awaited light,

Of heaven’s rising Sun comes smiling down, . . . 31

In the poem’s first line, Mary is blessed and honored among women, as in Elizabeth’s salutation in the Visitation: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” (Luke 1:42). Miraculously pregnant, Mary is the vessel of Christ, the “Temple of God’s Son.” Significantly, Revius’s words for son and sun (soon and sonne in Dutch) resemble sight rhymes and sound nearly alike, thereby connecting the light of the morning “sun” to God’s “son.” The rising sun that “comes smiling down” announces the joy of the incarnation. Thus, the rising of the sun in the poem, as in the painting, is a metaphor for the new faith in Christ, invoked by Zacharias’s messianic prophecy that the “dayspring from on high hath visited us. To give light to them that sit in the darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace” (Luke 1:78–79).

The African servant in The Visitation is thoughtful as she listens to Elizabeth and Mary express astonishment that the Lord chose them, women of humble origins, to play a part in the new faith (see fig. 3). Elizabeth asks Mary, “And why has this happened to me, that the mother of my lord comes to me? For as soon as I heard the sound of your greeting, the child in my womb leaped for joy” (Luke 1:43–44). Mary replies to Elizabeth by voicing the famous Magnificat prayer that expresses her own wonderment that she of “low estate” was favored by God: “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden; for behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed” (Luke 1:46–49). Thus, the servant in The Visitation hears the words of the holy women as she begins to understand that the new faith also embraces her—an African servant. Her involvement in this sacred event also signifies her own elevation, as she stands on tiptoe to remove the cloak (fig. 1b).

Rembrandt’s Amsterdam and Dutch Trade

The naturalism of the maidservant’s pose and facial expression, and her African mode of dress, seem connected to lived experience. Rembrandt would have encountered free, indentured, and enslaved Africans in the Breestraat (1631–34), the nearby Vlooienburg area (1635–1638), and, from 1639 to 1658, in the vicinity of his house on the Breestraat, where he interacted with his merchant Sephardic neighbors as well as African laborers, sailors, and servants. The presence of Black people in Rembrandt’s neighborhood in the early seventeenth century is reported by Ernst Brinck, a visitor to Amsterdam: “Most of the Portuguese, being largely Jews, live in Breestraat, and also have a house where they gather [a synagogue]. Almost all their servants are slaves and Moors [Black people].”32

Amsterdam was a major center of trade in the United Provinces, with a “multitude of strangers in shipping there,” as reported by the traveler Peter Mundy in 1640.33 The presence of Africans would have been a reminder of human trafficking that, for the Dutch, began in 1630 with the capture of Recife (in Pernambuco, Brazil) from the Portuguese, followed immediately by the arrival in Brazil of a WIC ship with 280 enslaved Black people.34 Six years later, 1,046 enslaved Africans arrived in New Holland (the Dutch colony in Brazil) from Angola.35 When the Dutch, under Johan Maurits of Nassau, captured Elmina (São Jorge) in West Africa in 1637, the power of the Portuguese on the Gold Coast of West Africa was crushed, and the WIC established a trade depot there.36 In April 1638, the WIC reserved for themselves commerce in slaves, dyewoods, and munitions but allowed private merchants to trade in sugar and tobacco with the payments of taxes, fees, and duties.37 The Dutch privateer shippers included Sephardic Jews, among other Amsterdam-based merchants.

Despite this intense activity, newspaper accounts in Holland remained silent on African enslavement until after 1661.38 Matters of commerce and warfare in Brazil, however, were regularly reported in Amsterdam, with a delay of three months, in corantos (news dispatches) and newspapers, especially after the WIC defeated the Portuguese in 1624 in the Brazilian state of Bahia, also known as São Salvador da Bahia de Todos os Santos (Holy Savior of the Bay of All Saints).39 From that victory on, and up to the defeat of the WIC in Brazil around 1654, Dutch Brazil became an ever-present topic in newspapers, corantos, and pamphlets, although, significantly, the topic of enslavement was elided.40 Dutch merchants and enslavers would not have appreciated reference to enslavement in these publications, since they were probably fearful that Amsterdam, which outlawed slavery in the city, would make it illegal in the colonies. The governor of Dutch Brazil, Johan Maurits, who cultivated an image of himself as a humanitarian, kept secret his extensive, clandestine, and illegal activities in the trade of enslaved people.41 His efforts, and those of others involved in the selling of forced labor, probably worked to suppress news in Amsterdam of these colonial activities.

The city was nonetheless the epicenter of information on Africa and the Atlantic world, which would have circulated beyond the confines of newspapers and pamphlets. Illustrated travel books, such as Pieter de Marees’s Beschrijvinge ende historisches verhael van het Gout Koninckrijck van Gunea . . . of 1602, were kept in the Oude Kerk for the use of travelers, merchants, and others who sought information on the people and geography of Africa and other remote areas. Residents of Amsterdam and foreign visitors also disseminated news about world events in the West India House, the Beurs (stock exchange), the Nieuwe Brugh (New Bridge), and the harbor, as well as in taverns, shops, and brothels. Moreover, seamen, merchants, and African immigrants shared their own experiences with others in the city. Rembrandt would likely have heard about events overseas from dealers of the curiosa (foreign objects) that he collected for his art cabinet. In view of this unending stream of information, the English diplomat Henry Wooten dubbed Amsterdam “a magazen [storehouse] of rumours.”42

Although Rembrandt had ample sources of information, we do not know how informed he was about—or if he took an interest in—the trade in enslaved Africans. In 1634 he painted lavish portraits of the wealthy sugar mill owner Maerten Soolmans and his wife, Oopjen Coppit, who imported raw sugarcane from slave plantations in Brazil.43 The raw sugar was supplied by a broker who would have informed Soolmans about the major role played by enslaved labor in the colony that supplied raw sugar to his mills. His wife may have learned about enslavement from Johan Stachouwer, the husband of her cousin who owned two highly successful sugar plantations worked by enslaved Africans in Brazil from 1629 to 1641.44 While painting their portraits, Rembrandt would have had the opportunity to discuss the colony and its enslavement of Africans with the couple—but whether such conversation occurred is another matter.

In this city of vibrant, global commerce, Rembrandt might have been cognizant that the scope of Dutch trade included human trafficking. It seems more likely that he would have been deeply curious about the Africans in his midst, especially Hester da Silva, his model. Perhaps her distinctive attire initially inspired him to include an African woman in his unique interpretation of the Visitation (see figs. 2 and 3).

Hester da Silva’s Life as an Enslaved or Free Woman

This study posits three plausible life stories for Hester da Silva. This approach may be compared with the notion of critical fabulation, a term coined by Saidiya Hartman that describes “a writing methodology that combines historical and archival research with critical theory and fictional narrative.”45 Hartman writes fictional stories gleaned from bits and pieces of archival research, giving voice to forgotten Black people, in her book of 1997, Scenes of Subjection.46 But in her 2008 article, “Venus in Two Acts,” based on a court case of 1792, Hartman elected not to write a fiction based on the brutality suffered by two slaves raped and killed on a slave ship. In her mind, to do so would only bring them back from the dead to display their violated bodies for posterity. The worst consequence of writing about the atrocity, Hartman argues, is that modern Black people will only consider the savagery of enslavement as their heritage.47 In accordance with Hartman’s admonition not to relegate persons of Black descent to an ancestry solely of enslavement and violence, the profiles offered here formulate two plausible, alternate modes of existence for Da Silva as a freeborn resident of Amsterdam.

The methodology applied here begins with the likeness of an anonymous figure in a painting by Rembrandt, but it does not write a fictional narrative of the model’s life; nor does it fill in the voids of the archive. Rather, it provides a generalized sketch that links her to other people of her time, situation, and place. The plausible profiles of the model in this study, like others, draw on historical evidence to insert Black people within the sociocultural context of colonialism and the cultural and economic life of Rembrandt’s Amsterdam. This method was employed in the Rijksmuseum’s 2021 exhibition Slavery, in which archival contextual evidence and/or visual materials touching the lives of known persons were displayed with textual documents and actual artifacts of the slave era.48

Historical events connected with the Dutch trade in Africa and Brazil, as well as visual and archival material, offer a rich contextual background for constructing a tentative sketch of the model’s life experience from a religious, political, geographic, moral, and sociocultural perspective. Da Silva’s plausible life experience as an enslaved person, the first of three profiles, begins with her birth in 1620 at Elmina Castle on the ivory coast of Guinea. Enslaved people captured from West and Central Africa were auctioned in Elmina by the Portuguese and transported to Brazil, where they were sold as forced laborers for sugar plantations, sugar mills, and households. The castle, built by the Portuguese in 1489, was used as a trade depot for gold, ivory, linens, and enslaved people. Africans and Moors captured and enslaved Black people in the interior of West Africa and brought them to Elmina, and the Portuguese transported them to Brazil and elsewhere for sale in the slave markets.

Hester da Silva’s light brown skin tone identifies her as an Afro-European Creole.49 Her hypothetical father was a Portuguese trader, official, or soldier at the garrison where her African mother worked, like others, as an enslaved domestic servant.50 Her first name, Hester [Esther], was common among the Portuguese and the Sephardim, since Queen Esther of the Old Testament was revered as a saint in Iberian culture.51 When Da Silva was born, she and her mother, and perhaps also her father, would have moved outside the castle into the village, as was customary for families with mixed-race children.52 Her father would have had the option of purchasing her freedom—but in this proposed scenario, he did not, as was usual.

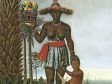

Da Silva’s earrings, headcloth, and especially her striped stole, tied in a distinctive manner around her hips, locate her origins in West Africa, on the Guinea coast. Her shawl resembles the voluminous cloth worn in the same manner by an enslaved African woman of the Gold Coast in an engraving from the costume book of 1797 by L. F. Labrousee, Costumes de Différent Pays, place Ghana (West Africa) (fig. 11). Much closer to the dates of Da Silva’s life is an illustration in Pieter de Marees’s popular Beschrijvinge ende historisches verhael van het Gout Koninckrijck van Gunea of 1602 (fig. 12), which portrays two women (A and C) wearing striped, draped cloth, one of which, identified as A, is labeled a “melata,” here described as a Creole of the Guinea Coast.

This type of striped textile, consisting of narrow strips of cloth sewn together, was woven by enslaved laborers on the coast of West Africa; it was also imported from India and sold as Guinea cloth. This type of textile was widely traded by the Portuguese for gold, ivory, and enslaved people at Elmina, where this speculative African woman was born and raised until she was fourteen years old, when she was sold into slavery in Brazil.53 Carrie Anderson notes that merchant ships laden with fabrics of many types chiefly traded on the west coast of the African continent.54 Blue-and-white striped cloth, dyed with indigo, was used by enslavers to clothe their newly purchased enslaved people, who were bought naked in the slave markets.55 Black people from the Guinea coast, like Da Silva, also wore blue-and-white striped textiles when they came to Brazil. In The Visitation, the model for the African wears a dark blue-and-white striped textile that appears black and white within the dark shadows (see fig. 2).

The pattern of Da Silva’s distinctive striped shawl is similar to that of the skirt worn by a free West African woman from New Guinea in Brazil painted by Albert Eckhout in 1641: African Woman and Child (fig. 13).56 Notably, Hester da Silva is barefoot, which also relates to her West African identity, since Black people residing on the Gold Coast and in West Central Africa from about 1600 went shoeless.57 Not only her attire but also her slight frame suggests her origins in West Africa. Caspar Barlaeus, echoing de Marees, asserted that enslaved people from Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Cape Verde in West Africa were “not as strong as those from Angola; and are not well suited for slave labor, but they are more civilized and show more taste for neatness and elegance, particularly the women, for which reason the Portuguese use them as domestic servants.”

In 1634, at the age of fourteen, this hypothetical Hester da Silva was sold at auction by the Portuguese in Elmina and transported by a long and arduous sea voyage to Brazil’s slave market, then under Dutch control, where she was purchased as a domestic by a moradores, a Christian Portuguese plantation owner. The Portuguese were allowed to stay in Brazil after the Dutch conquest of 1630 but were known to treat their enslaved people badly, as recorded by Zacharias Wagener (1614–1668), a clerk in the colony. He thought it a good idea to brand them “with a hot iron on their chests or necks,” so they could be recognized when they ran away from their enslavers.58 Da Silva’s life in Brazil working for the Portuguese would have been difficult.

In this scenario, around 1637, at the age of seventeen, Da Silva was purchased by a Sephardic trader, who took her to Amsterdam to work as a domestic in his household. Black women in Rembrandt’s neighborhood often served as enslaved or free domestic servants in the homes of Sephardic merchants.59 Lydia Hagoort reports that the number of Black people in Amsterdam was not large in the 1630s, when about fifty Africans had direct connections with the Sephardim.60 Da Silva worked for a wealthy Portuguese-Jewish merchant who lived on the Breestraat, where Rembrandt bought a house in 1639. She would have been one of many servants in the merchant’s large home, so her workload would have been on the light side, giving her time to wander in the neighborhood. Rembrandt may have seen her through the window of his house or on the street around 1640 and been attracted by her appearance and attire.

One wonders what Da Silva’s life as a servant in a Jewish-Portuguese home in Amsterdam would have been like. Mark Ponte’s extensive archival research on the Black residents of Rembrandt’s neighborhood, together with social research on the Sephardic community in Amsterdam and other material, prove useful in postulating the model’s experience.61

Hester da Silva’s Life and the Sephardic-Portuguese Community in Amsterdam

Many of the Iberian Jews of Amsterdam settled there about 1600, after fleeing the Inquisition in Portugal. Some Sephardic Jews had been banished to Brazil by the Portuguese Inquisition for reverting to Judaism.62 Many emigrated to such other cities as Hamburg, Emden, Haarlem, Mantua, Rouen, Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Nantes but were later motivated or compelled to leave some of them. Jews had to negotiate their admission to some of these cities by offering their expertise in trade and finance.63 This was crucial for Jews in Amsterdam, since they were restricted from holding public office, joining guilds, and engaging in retail, trades, and certain professions.64 The Sephardim considered themselves fortunate; they were neither compelled to wear badges or hats identifying themselves as Jews nor restricted to a ghetto, as in other places, and, most importantly, they were able to practice their religion in private. But the threat of deportation hung over their heads. Calvinist preachers railed against the Jews, and Gisbertus Voetius, Calvinist rector of Utrecht University, even led a debate in 1636 as to whether it was better to expel or kill them.65

With the conquest of the Portuguese colonies in Brazil, the WIC needed Dutch settlers and invited Amsterdam Sephardim to migrate to Brazil. They came by the hundreds, mostly to Recife (Pernambuco), the thriving sugar colony that heavily depended on forced labor from Guinea and Angola.66 Jewish immigrants were known to Portuguese Catholics in Brazil as “New Christians” or, more derogatively, as marranos (pigs or pork), because they had been forced to convert to Catholicism but did not observe it in the colonies. The Sephardic settlers did not play a dominant role as plantation or mill owners but were involved in the slave and sugar trades as financiers, brokers, and exporters of sugar; some sold slaves from Elmina on credit to the moradores in exchange for a future portion of the sugar crop.67 The Portuguese Catholics, however, wanted to bring in the Inquisition, and the Dutch Protestants wished to expel the Jews from the colony, so life there was not without its challenges.

Yet the Sephardic Jews enjoyed religious freedom in the robust Jewish community in Recife, which built its own synagogue around 1636. But this all ended around 1654, when the Portuguese reconquered Brazil from the Dutch, expelled Dutch inhabitants, and brought in the Inquisition. The loss of Brazil was essentially the end of prosperity for most Sephardic merchants, since only a few families like the Nassys, Pintos, and Belmontes became very wealthy and engaged in the slave trade, mostly in the Caribbean—but that history goes well beyond the years surrounding 1640.68

There are several possible reasons why Dutch Sephardic merchants might have brought slaves to Amsterdam to work in their households. The Iberian Jews may have become attached to their servants in the colonies and understood that they would be better off in Amsterdam, where enslavement was technically illegal and they could become free. Portuguese enslavers in Brazil were known to be cruel, so presumably things would be easier in Amsterdam for enslaved people who had become valued members of Sephardic households. Jewish-Portuguese merchants would have favored Africans from the Guinea coastal ports because they spoke Portuguese pidgin.69 Hester da Silva would have been especially desirable as a servant, since she grew up with and worked for the Portuguese and knew the language. Moreover, Black, non-Christian servants solved a major problem for Amsterdam Jews who wished to have servants, since Jews were forbidden to employ Christian maids, as stated in Article 29 of Hugo Grotius’s Remonstrance Concerning the Regulations to be Imposed upon the Jews in Holland and West Friesland of 1616.70

The Sephardim, on some level, may have been sympathetic to their Black servants, since in Iberian culture and elsewhere in Europe, Jews were regarded as racial Others and as people of color with “tainted blood.” Sephardic Jews in Portugal were denigrated by comparisons with African “blacks.” In a debate set up by the Portuguese Inquisition in 1640 with Isaac de Castro, the young Sephardic Jew refused to renounce Judaism, and the priest concluded that “it seemed to him that it is impossible for the Jews to repent of their errors, as it is impossible for the Black to change his skin.”71 Sephardic Jews were well aware that they were considered “black,” even as late as 1679. In the dedication of a work that year in defense of Judaism, Las Excelencias de los Hebreos, published in Amsterdam, the Sephardic, former converso, Ishac Cardoso, quoted from the Song of Songs (1:6): “I am black but beautiful; do not look at me because I am blackened (degraded), because the sun blackened me.”72

Travelers to Amsterdam dwelled upon the dark pigmentation of the Sephardim. Peter Mundy in 1640 claimed that Jews could be identified from others because they were “black.”73 William Brereton, who came to Holland and visited a Sephardic Sabbath service on June 14, 1635, wrote of “their men most black, full of hair, and insatiably given unto women.”74 Ironically, the Sephardim, who had been raised under the stigma of the supposed impurity of their blood in Iberia, continued to value white skin.75 Jews always lived in fear of expulsion and needed to avoid angering their Calvinist neighbors. Precipitated by the risk of reprisals for converting Black people, the governing Council of Elders of the Ma’Amad issued bans in 1627 and 1639 against bringing non-whites into Judaism. The Sephardic community was aware that Article 25 of Hugo Grotius’s Remonstrance Concerning the Regulations to be Imposed upon the Jews in Holland and West Friesland of 1616 stipulated that Jews were not permitted to convert Christians. Conversions of Africans would have been additionally unwise because some had been proselytized by Iberian Catholics.76

The Ma’Amad adopted some restrictive ordinances for Black people and Creoles that ran counter to the tenets of rabbinic Judaism.77 A law of 1627 relegated the burial of Black and mixed-race Jews to the periphery of the Hebrew cemetery at the Oude Kerk. This decree paralleled similar policies for Christian burials. Yet, despite ordinances passed by the Ma’amad, many members of the Jewish community chose not to follow the council rules. Some situations reported in the archives suggest a relationship of affection, economic support, and respect on the part of Sephardim for their Black servants. A headstone in the Oude Kerk, for example, marked the grave of the bom servo (good servant) Eliezer, who in 1629 was buried in the most prestigious section, among the founders of the Amsterdam Jewish community.78 These acts of decency toward African servants by Iberian Jewish merchants and their families went beyond burial practices. Some Black servants, such as Marguerita Fonça, were paid by their households;79 one Juliana was set free;80 and Luna and her daughter Esther received an inheritance from the woman who brought them to Amsterdam from Brazil.81

This speculative Hester da Silva benefited from the kindness and generosity she received from her Sephardic family, even if, from a modern viewpoint, such benevolence on a personal level cannot mitigate the suffering, injustice, and tragic consequences of enslavement itself. Hypocrisy on the issue of slavery was pervasive in the seventeenth century. For instance, the wealthy Sephardic slave plantation owner David Nassy harshly condemned the Danes for their “execrable inhumanity” for kidnapping twelve free Indigenous people from Greenland to take to Copenhagen in 1605/1606.82 And, as noted above, Maurits, the governor of Dutch Brazil, cultivated an image of himself as a humanitarian while smuggling slaves into Brazil.

Following Hartman’s advice to create a biography outside of enslavement, two more plausible profiles offer scenarios for Rembrandt’s model’s life as a free woman. Da Silva, in the second scenario, was born free and raised in a Sephardic home, much like Debora Nassy, a Creole in David Nassy’s family. David Nassy, who later became a slave holder in the Caribbean, declared before an Amsterdam notary that Debora Nassy, “the brown or mixed-race female [who acquired his name] was a free woman, conceived and born in freedom, and also raised as such, without anyone in the world having any kind of claim on her person.”83 Da Silva may have been an Afro-Jewish daughter of a Black maid and a Sephardic man living in the same household, who may have given her his surname, like the Nassy family. Ponte notes that Sephardic families had relatives of mixed descent.84 As required by the Ma’amad, Hester da Silva and her mother would have been monetarily supported by her father, who, like others, was quite generous to them.85

The third scenario proposes Da Silva’s life as a free, independent Black woman in Amsterdam. She could have left the household to live independently—like any other enslaved servant in Amsterdam, since slavery was illegal in the city, and authorities would not pursue or punish her. Having gained her freedom, she could have converted to Christianity and joined the free, independent African community in Rembrandt’s neighborhood, led by Hester Jans van Capo Verde, who witnessed baptisms in 1627 and 1631.86 This Hester da Silva married a free Afro-Brazilian seaman who worked for the WIC or VOC companies and supported her family by renting out rooms to sailors and others.87 The Portuguese-Israëlitische Society and Protestant charitable groups were known to support poor Black people in the city, although this hypothetical Hester da Silva and her family did not fall into destitution.88

Hester da Silva and the African Servant: Texts on Colonialism and Enslavement

The Dutch reception of both Hester da Silva as an individual and Rembrandt’s painted servant (fig. 3a) may be posited by consulting contemporaneous writings on colonialism and enslavement by Willem Usselincx (1608), Gerbrand Bredero (1615), Hugo Grotius (1625), Godefridus Udemans (1638), Johannes de Laet (1644), and Caspar Barlaeus (1647), among others.89 These sources offer wide-ranging, often overlapping opinions on the economics, legality, morality, and religious and political objectives of colonialism and enslavement. Some of these writers were Calvinist ministers whose published sermons were widely read and echoed by other clergy. The following discussion of these texts, however, does not in any way presuppose that Rembrandt would have consulted them; rather these sources offer a glimpse of the discourse then circulating in the vibrant, mercantile city of Amsterdam in the 1630s and 1640s.90

The oft-quoted lines in act 1, scene 1 from G. A. Bredero’s popular play Moortje (Little Moor) are famous for their bitter indictment of slavery:

Inhumane custom! Godless rascality!

That men sell human beings, into horselike slavery!

In this too there are those, who engage in such trade [referring to Jews]

In Farnabock [referring to trade in Recife, Brazil]:

but it cannot be concealed from God.91

This burlesque comedy was first performed in Amsterdam in 1615, but Rembrandt could have attended productions in 1637, 1638, 1644, or 1646.92 An adaptation of an ancient Roman comedy, Terence’s Eunuchus, Bredero’s Moortje is set in the bustling mercantile world of late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Amsterdam, with the titular character of Negra, an enslaved woman from the Portuguese colony of Angola, played by a Black actress. Her white counterpart in the play is a Dutch maiden named Katryntie, enslaved by Muslims but later purchased from bondage. The comedy hints at the hypocrisy of the young Ritsart, who voices the above lines condemning slavery but is himself the enslaver and abuser of Nigra.93 Scholar Anston Bosman explains that Ritsart’s famous harangue against slavery refers not to Nigra’s enslavement but to Katryntie’s former captivity by Muslims.94 Ritsart’s double standard, in condemning slavery while ignoring Nigra’s enslavement and his own culpabilities, was not unique in Rembrandt’s time. Such self-delusion informed contemporaneous attitudes toward enslaved Black people.

The “humanist” justification for slavery, based on Lucius Seneca (d. 65 ce), was advanced by the highly respected and influential Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) in 1625.95 While Grotius admitted that slavery was not a natural condition for humankind, he viewed the institution itself as compassionate, since prisoners of warfare who would otherwise be legally killed were preserved from execution by being sold into bondage. He exhorted enslavers to treat their forced workers with fairness. If beaten or otherwise abused, enslaved people were justified in running away. These “humanist” ideas widely permeated seventeenth-century attitudes toward slavery. Such legal justifications allowed people to dismiss any scruples they may have had regarding the morality of enslavement. A form of connivance, this excuse may have been the accepted view for many of Rembrandt’s compatriots, if not the artist himself.

To differing degrees, authors stressed religious, political, and commercial concerns when treating the subject of colonialism and enslavement. Calvinist supporters of the slave trade used the Bible to justify the use of forced labor. Many argued that persons of African descent came from the accursed race of Ham, whose son Canaan was condemned by God to a life of servitude for disgracing Noah, his grandfather (Genesis 9:18–27).96 In essence then, people believed God to have designed the enslaved condition of Black persons, even though this aspect of the story is not told anywhere in the Bible.

A founding director of the WIC, Johannes de Laet (1581–1649), was “an ardent champion of the Dutch Reformed Church.”97 He expressed his opinions on Dutch trade in the introduction to his book of 1644, Historie ofte Iaerlyck verhael van de verrichtinghen der Geoctroyeerde West-Indische Compagnie . . . (History or Annual Account of the Transactions of the Chartered West India Company . . . ). De Laet fused politics and religion when he claimed the WIC was founded for the honor of God, the “maintenance of the True Religion, and the protection of our freedom.”98 He considered the real enemies of the Reformed Church to be Catholic Spain and Portugal. As director of the WIC, de Laet did not oppose slavery, since he viewed human trafficking to be a commercial necessity.

Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), a founder of the WIC and resident of Middelburg, was foremost among the Calvinists who touted the economic and religious benefits of colonization under the banner of the WIC, although he opposed slavery on financial grounds.99 In a pamphlet of 1627, he argued that many enslaved people who were forced to do hard work would not marry because their children would also be enslaved; therefore, they would not procreate, and more slaves would have to be purchased annually, making it very costly.100 Usselincx, like de Laet, believed that God commanded the spread of Christianity (specifically Calvinism), “by God’s grace to bring Black slaves to the knowledge of the true God and be brought to spiritual freedom,” setting the Protestant missionary effort in opposition to the missionary activities of the Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits and monks.101

Usselincx emphasized the need to “civilize” the Indigenous people of conquered lands in a pamphlet of 1627. The first job of the colonist on arrival was to “immediately clothe the wild Indians who run naked; we must slowly civilize them through interactions with us and conversion and instruction.”102 To achieve his missionary goals, he implored the WIC and the States General to establish theology colleges to train teachers to destroy the “devil’s reign” of Catholicism and “plant true religion in the colonies with good preaching and a mild hand.”103 A seminary was set up in Leiden in 1622 to train missionaries for this purpose.104

Other Calvinists also sought to evangelize pagans of non-Christian lands. The theologian Gisbertus Voetius (1598–1676) adhered to the Second Reformation (Nadere Reformatie; c. 1600–1750), a religious reform movement committed to church reform and the “planting of new churches.”105 He supported the Canons of the Synod of Dort (1618–1619), which encouraged missionary work directed toward pagans and other non-Christians.106 The Synod Canon (Chapter 2, Article 2) inspired Voetius to write the treatise De plantations ecclesarium (1648–1669), which commanded that the gospel be declared to all people, including so-called heathens, and all nations, without differentiation or discrimination.107 All humanity, he explained, requires salvation because of sin (Chapter 3, Article 1), but predestination means that the saving grace of God is not universal: some will be saved, others not. He cautioned that conversion, faith, and church membership are prerequisites to receiving God’s grace (Chapter 1, Article 2, 4). Voetius also claimed that it was acceptable to purchase slaves, so long as they received humane treatment. Their conversion, however, would likely have to be postponed, since he considered Black persons resistant to Christianity.108

Like Voetius, Godefridus Udemans (1581–1649) fostered missionary work to civilize and convert the Indigenous people and Africans of the colonies and establish a Reformed church in the New World. One of the most famous preachers in Zeeland, Udemans was asked by the members of the WIC and VOC to prepare a report on the morality of slavery in the colonies. His response appears in ‘t Geestelyck roer van ‘t Coopmans Schip (The Spiritual Rudder of the Merchant Ship) of 1638 and 1640.109 Udemans sets forth the goals of the publication on the title page, where he recommends good behavior to merchants in the colonies.110 On the front page appears the phrase: “Steer rightly the rudder of the Merchant ship, or otherwise run onto sand or rock.”111

Udemans believed that the conversion of Africans and Indigenous people would precede and hasten Jewish conversion, thus ushering in the anticipated Millennium.112 He quotes from Luke 14: 21–23 in urging ministers to “go out into the highways and hedges” and compel others “to come in, that my house [church] may be filled.”113 Udemans considered the suffering of enslaved people minimal when compared to their bondage to sin and the devil—the spiritual slavery suffered by those without God’s election and grace. In his mind, the true release from enslavement was through conversion, faith in Christ, and the True Church.114 As expressed by Udemans: “One pious man is free, even if he were a slave: but one evil man is a slave, even if he were a king.”115

These views align with those of Usselincx and Voetius on the missionary goals of conversion and the founding of new churches as a means of imparting civility and discipline to the Africans and Indigenous people of the Americas. He also considered the acquisition of wealth through “ethical” slave trade and hard work to be a blessing of God.116 Like many other supporters of the slave trade, Udemans followed the “humanist” principles set forth by Grotius in his prologue to De Jure Belli ac Pacis (The Laws of War and Peace) of 1625.117 Udemans offered Africans and Indigenous people an incentive toward conversion by recommending that those who became members of the Reformed Church be released from enslavement after seven years.

Grotius’s “humanist” concepts of slavery, as well as the conversionist mission of the Calvinist ministers, coalesce in Caspar Barlaeus’s celebratory history of Johan Maurits’s governorship of Dutch Brazil, Rerum per octennium in Brasilia (Thoughts on Eight Years in Brazil) of 1647. This large compendium was highly respected, even though the author never set foot in Brazil. He assiduously gathered material from numerous earlier sources and spared no words of praise for his patron. Among other matters, Barlaeus attempted to tackle the Christian dilemma of justifying enslavement: “Perhaps it was now considered sinful to enslave God’s children, who had been redeemed by the blood of Christ, or it was thought that these new and unusual humanitarian ideas might convert the pagans to Christian doctrines.”118 Barlaeus, like Grotius, resorted to the Stoic philosopher, Lucius Seneca, on the just treatment of enslaved people: “Are they slaves? No, they are human beings. Are they slaves? No, they are your companions, who share your household. Are they slaves? No, they are your humble friends. . . . It is cruel and inhuman for us to abuse them as though they were animals rather than human beings.”119 These differing attitudes toward enslaved persons and the slave trade shed light on the complexity of determining how Rembrandt and his contemporaries might have viewed the artist’s model and the African servant in The Visitation.

Conclusion: Global Reach, Reception, and Toleration

This article explores three essential areas of concern: the iconographic analysis of Rembrandt’s The Visitation (1640) within a broad, cultural sense; the investigation of the sociocultural context in which it was created; and the critical imagining of the identity of Rembrandt’s model, which brings the first two considerations together.

In sum, the Black servant in Rembrandt’s The Visitation is a significant rather than marginal figure. Her unprecedented inclusion invokes the universality of the new faith and her access to it, particularly as conveyed by Rembrandt’s unique staging, his use of light evoking the dawn of Christianity, and the woman’s reverent facial expression and authentic West African attire. This interpretation, based on the account in the Gospel of Luke, wholly conforms with Erasmus’s commentary on the Visitation and inflects Revius’s poem “Mary.”

To the question of how this African servant was received by Rembrandt’s contemporaries, writings by Willem Usselincx, Godefridus Udemans, Johannes de Laet, and Gisbertus Voetius suggest they would have seen the Black woman as undergoing a conversion from paganism—the realization of their missionary goals to spread the Reformed faith throughout the globe, in opposition to Spanish and Portuguese Catholics. But most Christians, whether Calvinist, Remonstrant, Mennonite, or Catholic, would have welcomed the conversion of an African to Christianity. For the artist’s contemporaries, African conversion was a step toward civility. Udemans considered African conversion a precondition for Christianizing Jews, to bring about the thousand-year rule of Christ of the Second Coming. Rembrandt may have thought the inclusion of the African servant in The Visitation would be attractive to collectors who embraced such views; however, we do not know when and to whom the painting was first sold. To correct the published record: The Visitation does not appear in the 1656 inventory of Rembrandt’s possessions, nor is there evidence that the collector Hieronimus van der Straten acquired it directly from the artist, as previously put forth by the Detroit Institute of Arts.120 The first mention of the painting appears in the 1662 estate of Van der Straten, burgomaster and alderman in Goes, Zeeland, where it was valued at the high price of 800 guilders.121 With his substantial investments in the WIC and VOC, Van der Straten would have known the economic advantages of enslaved labor, vigorously pursued by Zeeland interests in the Caribbean. Moreover, like Udemans, the collector may have considered the acquisition of wealth through “ethical” slave trade and hard work to be a blessing from God. Further research may lead to stronger conclusions on these matters.

The three plausible profiles of the model—as an Afro-Portuguese Creole born in Guinea, sold to Brazil, and brought to work in a Sephardic home; as a free Afro-Jewish member of a Sephardic household; or as a free woman living independently—are all designed to bring her into our own historical consciousness and reveal her agency. When asked in a public lecture how to move Black individuals out of the shadows when there is so little material with which to do so, the scholar Elmer Kolfin recommended the study of context;122 these well-informed profiles are an attempt to do just that. The plausible sketches of the model’s life give substance to the modern viewer’s reception of the African maidservant in Rembrandt’s painting. Thus, the two women, Hester da Silva as Rembrandt’s model, and the painted African servant, coalesce into one in The Visitation, much as they did in Rembrandt’s own imagination—offering insight into his invention of the figure from life to his art.

The method employed here may prove useful within a museum setting, as it may encourage visitors to look closely at seemingly marginalized people or others in the shadows and discover their reconstructed place in history. More work needs to be done on images of Black people in seventeenth-century Dutch painting. One case in point is Rembrandt’s large painting Two African Men, ca. 1656/1666, in the Mauritshuis, which would greatly benefit from plausible profiles of the two figures and their known relatives—especially since they are tentatively identified by Mark Ponte as the brothers Bastiaan and Manuel Fernando, sailors from the island of São Tomé (fig. 14).123 Indeed, Ponte’s identification of these men is a rare, valued instance in which actual names may be assigned to images of anonymous Africans.

But what may be said about Rembrandt and the toleration of Black people? The term itself must be clarified to address this question within a historical context. Douwe Fokkema and Frans Grijzenhout offer a modern view of “tolerance” that opposes the changing of others into ourselves.124 True tolerance, they posit, is the virtue of respecting others in their very differences.125 It is highly doubtful, however, that Rembrandt or his compatriots would have shared such modern-day notions of toleration. Nor could the artist conform to the socio-political conceptions of race and morality that we know today. Present-day viewers of the African servant in The Visitation, for instance, might be critical of her subservience to white people and condemn the supremacy of Christianity over paganism implicit within this work of art; yet one could gain insight on modern-day habits of racism by studying Rembrandt’s painting within his own time and place. Even the harsh denunciation of slavery in Bredero’s play Moortje references the Muslim bondage of a white woman, rather than the enslavement of the African, Nigra. Influenced by Grotius’s legal theories, Hollanders may have defended slavery by observing that African captives in war, who could legally be killed, were instead saved from execution by being sold into enslavement (Grotius also indicated that slaves could run away if they were treated unfairly). Above all else, Amsterdammers probably considered locals of African descent fortunate to reside in a city where enslavement was illegal. Indeed, this might have been the excuse for slaveholders like the Sephardim, who were reported to be kind and generous to their servants but, like others, did not challenge the institution of enslavement. Such ideas eased the scruples of many who may have harbored doubts about slavery’s morality.

Admittedly, it is difficult to fathom precisely what Rembrandt believed. He was foremost an artist, not a philosopher or a social historian. While he undoubtedly possessed a gift for capturing the inner lives and emotions of his figures, no matter their race or religion, such a talent does not predicate a tolerance toward others by either today’s standards or those of the past.126 What we do know is that, as an artist, Rembrandt had an abiding interest in the dress and appearance of the diverse people he encountered in his world, not only Africans, but also Jews.127 Philipps Angel praised Rembrandt in 1642 for his research on the details of clothing, textiles, and domestic artifacts in his works.128 Indeed, Rembrandt collected objects from around the globe for his own pleasure and for the sake of his art, and he portrayed foreign people hailing from the four quarters of the earth in his grisaille of 1634, The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist (fig. 9a). This global reach informed his unique, timely, and substantive interpretation of The Visitation, with the maidservant based on an African model in Rembrandt’s neighborhood, dressed in the traditional cloth of the Guinea coast.