The curious anecdote in Karel van Mander’s biography of Bruegel, where the artist is said to have swallowed all the mountains and rocks during his crossing of the Alps and spat them out again onto canvas and panels upon returning home, has been quoted by almost every Bruegel scholar. Yet it has never been given a full explanation. In this study, it is proposed that the passage, echoing on one level Bruegel’s frequent depiction of overindulging peasants, disguises a highly cultivated reference to the theory of imitation as a digestive process, or innutrition theory, which was widely used by humanist writers of the time to champion vernacular expression.

For Michel Weemans

Under so mean a form we should

never have picked out the nobility and

splendour of his admirable ideas

—(Michel de Montaigne, Essays, Book 3, p. 12).1

Some books are to be tasted,

others to be swallowed and some few to be

chewed and digested

—(Francis Bacon, Of Studies)2

In Les couilles de Cézanne (Cézanne’s balls) Jean-Claude Lebensztejn recounts a quite striking but equally forgotten anecdote about the great artist: “Gauguin relates how in 1879 or 1880, while [Cézanne] was painting out of doors in Médan, a passing walker claiming to be a former pupil of Corot offered to rectify his landscape. Cézanne scraped away the gentleman’s additions with an acid remark and then, after a moment’s silence, let out a great fart accompanied by the words: ‘Ah! That’s better.’”3 Far from the image of Cézanne the theoretician, so beloved of art historians, the anecdote clearly shows the artist brazenly farting in the face of academism and established tradition. In this story Cézanne is the seeker after “truth in painting,” the man who would explain later, to Émile Bernard: “It is my view that art can be attained only if we take nature as our starting point. The great error of art as taught in Museums is that it upholds methods which distance us absolutely from the observation of nature, which should be our guide.”4 Unabashedly scatological, this anecdote is perhaps more theoretical than it first appears. And while Cézanne stops short of directly associating his irreverent fart with his quest for the true, authentic, imitation of nature, he has an important predecessor in Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in whose work these two paradoxical, apparently conflicting, characteristics are profoundly linked.

The following argument takes, as its starting point, the curious anecdote in Karel van Mander’s biography of Bruegel, where the artist is said to have swallowed all the mountains and rocks during his crossing of the Alps and spat them out again onto canvas and panels upon returning home; a famous quote that has never been given a full explanation by Bruegel scholars. The anecdote is, like Cézanne’s story, more theoretical than it seems and will allow us to explore the little-discussed tension in Bruegel’s work between vulgarity and obscenity on the one hand, and the imitation of nature on the other. More specifically, I want to suggest that Bruegelian obscenity not only opposes and satirizes the dominant artistic theory of its day, namely the classicizing Italian model,5 but that it also, perhaps more subtly, masks—in a kind of paradoxical eulogy—a highly developed and sophisticated theoretical reflection on the imitation of nature. In the last part of the paper, I address more broadly the question of digestion, vomiting, and defecation in relation to Bruegel’s oeuvre, questioning the theoretical function played by the figure of the kakker in his paintings and locating it within the larger cultural framework of medical knowledge and contemporary literature.

This essay draws on a number of studies over the past twenty years, which have sought a better understanding of the grotesque, parody, and satire in humanist thought and artistic and literary production during the Renaissance.6 The concepts of paradoxical eulogy and satire, inherent in the language of inversion and diversion, are present in antique literature and especially in the rhetorician Lucian of Samosata. In painting, they are expressed in the work of artists categorized by Pliny the Elder as rhyparographers—painters of everyday, repugnant, or base subjects—as opposed to the “high” painters of noble subjects, known as megalographers.7 In the Renaissance, paradoxical eulogy and satire are taken up by Erasmus and Rabelais, each in his own way appropriating and elaborating on Menippean satire by adapting it to the expectations of Christian humanism.8 The hermeneutic implications of these literary genres had their pendant in painting, too. Reindert Falkenburg has shown how Pieter Aertsen’s grotesque peasant figures—and their revival of the antique rhyparographers’ art—would have been understood in relation to this comic, parodic genre, at the margins of a cultural hegemony characterized by its reverence for the art of antiquity and the great Italian masters.9

This notion of paradox (para-doxa) lies at the heart of Pieter Bruegel’s work, too, as argued by Jürgen Müller in his study Das Paradox als Bildform: Studien zur Ikonologie Pieter Bruegels d.Ä., in which the author draws abundantly on contemporary literature, in particular the writings of Erasmus and Sebastian Franck.10 Recently, Michel Weemans’s magisterial monograph on Herri Met de Bles has further enriched this approach, showing how the latter’s landscapes function as a kind of visual exegesis: the paintings are not content to illustrate a text or to imitate a specific place. Rather, through the inclusion of often grotesque, improbable details, they visualize an interpretation of that text, engaging the viewer in a hermeneutic process that demands a conversion of the act of looking, from physical seeing to intellectual insight. Emblematic of paradox and the disruption of the senses, the figure of Silenus is central to this interpretative principle, both in paintings by Bles and in the contemporaneous writings of Erasmus and Rabelais (who includes him in the prologue to Gargantua). Both authors see Silenus as an ugly, buffoonish figure—not only a sylvan mythological creature, the adoptive father of Bacchus, but also and more specifically a reference to the Sileni of Alcibiades in Plato’s Symposium: small grotesque statuettes carved in such a way that they revealed a divine figure, a treasure concealed in their chest, to whoever managed to open them. In this game of serio ludere, so characteristic of Renaissance humanism, the Silenic figures invite the viewer/reader to look beyond what they see at first, to grasp the wisdom and profundity beneath the comic, grotesque, obscene surface.11

Peasant Bruegel and the Italian Model

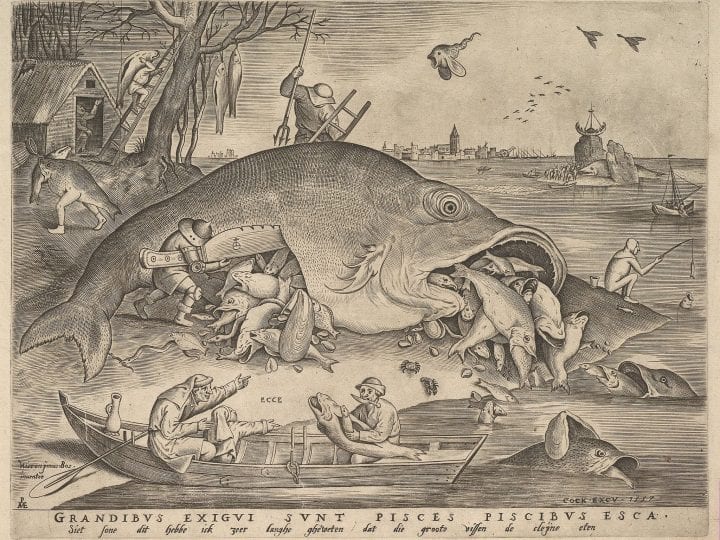

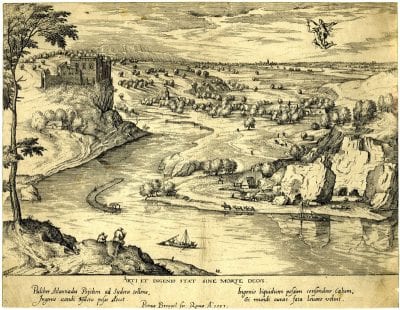

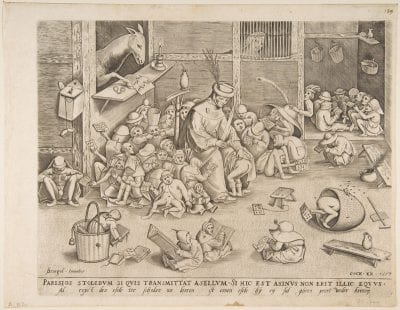

Let us start with the interpretation of the celebrated, often-quoted passage in Karel van Mander’s biography of Bruegel, written for his Schilder-Boeck (Book of Painters), published in Haarlem in 1604. The passage reads: “On his travels he drew many views from life so that it is said that when he was in the Alps he swallowed all those mountains and rocks which, upon returning home, he spat out again [regurgitated] onto canvas and panels, so faithfully was he able, in this respect and others, to follow Nature.”12 In mentioning the journey through the Alps, van Mander refers to the celebrated series of Great Landscapes, presented by Bruegel to the publisher Hieronymus Cock on his return from Italy in 1555 (fig. 1).13 Soon after, Bruegel created burlesque and grotesque compositions, which quickly earned him the nickname “the new Hieronymus Bosch” (fig. 2).14 The Great Landscapes reinterpreted the Weltlandschaft tradition (inaugurated by Patinir) in the light of Italian landscapes by Titian and Campagnola, while at the same time distancing themselves quite deliberately from the Italian model favored by Flemish painters such as Hans Vredeman de Vries or Frans Floris. Bruegel preferred instead to embody and extend a resolutely Dutch vernacular artistic vocabulary characterized by the importance of landscape but also by the figure of the peasant or countryman, the “primitive Batavian,” coarse and bawdy but decent and amiable nonetheless, the object of renewed interest among Flemish and Dutch historians of the time, and categorized by most art historians as belonging to what Hans Joachim Raupp called the genus satiricum (satirical genre) (fig. 3).15

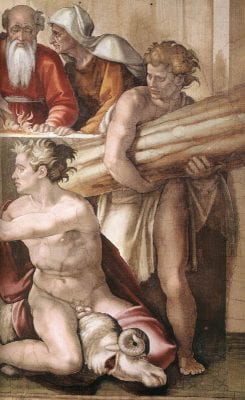

Bruegel does not deny the Italian models: rather than quoting from them, he absorbs and ingests them. In his famous Berlin drawing, one of the beekeepers is directly inspired by a figure painted by Michelangelo for Noah’s Sacrifice on the Sistine Chapel ceiling (fig. 4a and fig. 4b). However, transposed to the Brabant, faceless and surrounded by hives, Bruegel’s figure echoes his model in pose alone.16 Similarly, the celebrated Vienna Tower of Babel takes the Roman Coliseum as the ideal embodiment of classical architecture, parodied here—in a sense—by its lopsided structure. Bruegel hints that the building is irremediably destined for ruin and destruction, perhaps an echo of humanistic commentary on the fall of Rome and neo-Stoic lament on the destruction of the “machina mundi” (fig. 5).17 In place of the ideal classical figure, Bruegel presents the stocky peasant, a faceless, headless body that subverts the nobility enshrined in contemporary canons as the ultimate goal of painting. Bruegel degrades his figures still further elsewhere: mutilated bodies in The Beggars (Louvre, 1568), blind bodies in The Parable of the Blind (Capodimonte, 1568), crouching figures defecating in the foreground in The Magpie on the Gallows (Darmstadt, 1568) (fig. 6). Other figures—notably in the celebrated series of the Seven Deadly Sins—have arseholes for mouths. In his disfigured bodies and mouths—gaping, monstrous, vomiting—Bruegel orchestrates a great symphony of viscera, digestion, and low bodily functions (fig. 2, figs. 7, 8a, 8b).18

And so we begin to see van Mander’s passage in a clearer light. The Bruegel who devours and regurgitates mountains is clearly a reflection of the imaginary world in his perennially fascinating, comical, and shocking paintings. In van Mander’s biography, Bruegel thus becomes a character in his own fictive world. Like his drunken peasants at country fêtes (see fig. 3), Bruegel has over-indulged in drawing (“he drew many views from life”),19 and his excesses ultimately lead him to regurgitate or spew out what he has ingested. This image of “Peasant Bruegel” is especially clear at the beginning of van Mander’s biography: “Nature found and struck lucky wonderfully well with her man—only to be struck by him in turn in a grand way—when she went to pick him out in Brabant in an obscure village amidst peasants, and stimulate him toward the art of painting so as to copy peasants with the brush: our lasting fame of the Netherlands, the very lively and whimsical Pieter Brueghel.”20 Van Mander had read Vasari’s Lives and based his biographies of northern painters on this Italian model, from which he borrowed the trope of natura sola magistra or “Nature as guide.” This topos attributes rustic, pastoral origins to painters whose works rival Nature herself and give prominence to studies taken from life (naer het leven); artists who are themselves children of Nature, then, still largely caked in the rustic dirt of their beginnings.

As Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz have clearly shown, Vasari constructed several of his artists’ Lives on this mythologizing model, beginning with Giotto, whose talent for imitating nature was revealed as he watched over his flocks in the countryside, as a young shepherd-boy; Domenico Beccafumi and Andrea del Castagno get the same treatment. Later commentators describe Zurbaràn’s or Goya’s childhoods in the same way; as does Passeri when speaking of Guercino. Van Mander uses the same formula to describe the early talents of Joachim Patinir, Herri Met de Bles, and Joris Hoefnagel. Joachim von Sandrart’s biography of Claude Lorrain is similar in intent, as I have shown in a recent article.21 Later in his Life of Bruegel, van Mander pursues his theory of the artist being reflected in his own work, when he reminds us that Bruegel would dress as a peasant in order to pass unnoticed when drawing (and often imitating) his oafish, drunken compatriots at village fêtes.22

Satirical Critique or Paradoxical Eulogy?

And yet, beyond its easily deciphered function as a commonplace trope, van Mander’s anecdote remains a curious, even incongruous inclusion in his select (and selective) narrative. We can picture Peasant Bruegel among the peasants at the kermis, but it is more difficult to imagine the same character trudging a path through the Alps—not quite the right scenery for revelry and binge drinking (see fig. 1).23 Most importantly: what does the image of ingestion and ejection have to do with the imitation of Nature? What is the causal link between the two parts of van Mander’s sentence (“so that it is said that when he was in the Alps . . . so faithful was he able, in this respect and others, to follow Nature”), between regurgitation and mimesis? Surveying the rich and extensive Bruegel literature, we find more than one commentator perplexed by the passage. It is quoted by the great majority of authors but with no attempt at explanation. The few who have tried insist on the connection between allusion to a dirtying action (spitting out or regurgitation) and the essence of Bruegelian “imitation,” which is diametrically opposed to Italian mimesis. Hence, for Bertram Kaschek: “The often-quoted remark that has Bruegel swallowing the rocks and mountains of the Alps and spitting them out on his return home, such was his fidelity to Nature, should be clearly understood as pejorative: Bruegel’s so-called realism is being criticized as raw and undigested.”24

Likewise, in a pioneering article on Bruegel’s rhyparographic figures, Michel Weemans’s interpretation insists on the tension between the Bruegelian landscape model and the tradition of Italian “fine painting”: for him, the metaphor is not a direct criticism of Bruegel but points to a negative reception of his approach to landscape.

Van Mander’s powerful metaphor expresses complete astonishment at a mimetic practice alien to the logocratic system of representation which has, like Floris’s work, perfectly digested the Italian precepts according to which “the hand obeys promptly when guided by reason.” In one sense, we might say that Van Mander’s remark echoes Michelangelo’s famous condemnation of Flemish landscapes, as recorded by Francesco de Hollanda, in which he scorns painting “done without art or reason, symmetry or proportion, without choice or discernment, without design, in a word without substance or sinew.”25

Kaschek’s and Weemans’s interpretations should not be misunderstood. Van Mander does not validate such criticism of Bruegelian landscape painting. Indeed, Walter Melion’s work on Karel van Mander (Shaping the Netherlandish Canon, 1991) demonstrates admirably how the Schilder-Boek—containing the first chapter on landscape painting ever included in a theoretical treatise on art—not only affirms the specific character of Dutch landscape but seeks to elevate it from the status of mere background painting to a paradigm for all visual representation, conferring upon it the same dignity as history painting. In short, van Mander is no Michelangelo. Quite the opposite. He enshrines Bruegel as the champion of Dutch landscape painters, comparing him with his Italian counterparts in the genre—Tintoretto, Titian and Muziano—and praising him for his ability to draw the eye into the depths of the picture and capture the immense varietas of the natural scene.26

Furthermore, we cannot be certain that van Mander’s superficially vulgar metaphor is intended “in the pejorative sense,” as Kaschek suggests, given that the author himself tried his hand at pictures of peasant festivities, in the Bruegelian tradition.27 A 1592 drawing of a country fête, engraved by Nicolas Clock in 1593, is one example (fig. 9).28 In addition to which, as Svetlana Alpers has pointed out, the accompanying legend—in van Mander’s own hand—suggests the opposite of a moralizing interpretation of the scene (which is directly inspired by Bruegel’s Deadly Sins; see fig. 8a): far from being criticized, the spectacle is accepted as commonplace, even defended. Another engraved version of the same drawing associates it with an indulgent Dutch proverb to the effect that “not every day is a holiday.”29 The image of debauched peasantry is not necessarily negative, then, in van Mander’s eyes, though the village festivities are essentially comic in their effect. Recent historical research into the association of the peasant figure with scatology and obscenity during the Renaissance also suggests that this was essentially comical and satirical in its aim and intent.30 Similarly, in the context of Dutch history, as we have seen, the peasant figure embodies the region’s Batavian past and is not so much denigrated for his primitivism as celebrated for his straightforward honesty and simplicity. This inversion is especially apparent in one of Erasmus’s Adagia, “the Batavian ear”: an epigram by Martial describing the ignorant condition of the ancient northern peoples is reversed in a celebration of the simple, good-hearted, straightforward character of Erasmus’s Dutch contemporaries.31

Ars and Ingenium: Bruegel and the Imitation of Nature

A negative interpretation of van Mander’s metaphor for the Bruegelian imitation of nature flies in the face of the positive re-evaluation of the artist’s work around 1600, not only in van Mander’s writings but among other contemporaries, too. One particularly interesting image serves to illustrate this point: an engraving by Simon Novellanus published by Joris Hoefnagel after a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (now lost), a copy of which exists in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Besançon (fig. 10). Dated circa 1590–95, when Hoefnagel was working at the court of Rudolf II in Prague, this splendid composition shows two draftsmen applying themselves to the depiction of an immense valley. The image thematizes the subject of drawing from nature, which is also the subject of the passage in van Mander’s biography.32 The engraving bears witness to the renewed enthusiasm—especially at the Prague court—for Pieter Bruegel’s work, the landscape genre, and, more generally, the representation of nature around 1600.33

The engraving’s Latin verse is inspired by Propertius,“Arti et ingenio stat sine morte decus,”34 and the figures of Mercury and Psyche spiraling in the air, clearly added by Hoefnagel, serve to underscore the perception of landscape painting (ars) as an appeal to the painter’s imagination or genius (ingenium) and a possible path to immortal glory. The details dignify the landscape genre, considered inferior in the art theory of the day, which continued to celebrate history painting as supreme.35 The engraving presents the draftsman in the landscape, no longer as a scrupulous but mechanical imitator of nature (naer het leven) but—on a par with history painters—as an artist producing a work of the genius and intellect (uit den gheest), gifted with spiritual powers which enable him to bring nature itself to life. The humanist Abraham Ortelius goes further still in his album amicorum—which circulated from 1574 to 1596—when he confides that Bruegel was not only the best painter of his generation, but also “Nature itself in paint” (natura pictorum). In this, he says, Bruegel is “worthy of being imitated by all.” Ortelius’s equation hints that the artist is not content merely to imitate the outward appearance of the natural scene (natura naturata); rather, he recreates the creative processes and power of Nature herself (natura naturans), and it is for this reason that his works must be imitated by others.36

It is in this context—the eulogy of the imitation of nature—that we should interpret van Mander’s “visceral” anecdote. The metaphor does not, in fact, allude to the raw, “undigested,” character of Bruegel’s art but rather to the act of digestion in the phenomenological sense of the term: the digestion of things seen, which will subsequently engender things represented. It is precisely this act of digestion that justifies the elevation of landscape painting to the status of history painting in the hierarchy of genres. The mountains and rocks are the raw materials that will be digested and transformed by the artist, even if this “creative,” profoundly positive transformation appears superficially disgusting and repellent (following the example of paradoxical eulogy inspired by Menippean, Erasmian, and Rabelasian literature). To my knowledge, Konrad Oberhuber is one of few art historians to have perceived this essential dimension, in his text on Bruegel’s early drawings:

We must rather see him as a master capable, in the first instance, of making fresh new observations from life and subsequently of assimilating these discoveries into the art forms and world view of his time. Van Mander’s famous phrase—that Bruegel “swallowed up” the mountains and “spat them out” onto the canvas—suggests at least some form of digestion taking place while the raw material remained within the artist’s body and soul. And indeed, in the impressive etchings of 1555 we find the fresh if raw material of the early drawings totally transformed by the artist’s personality, as similarly expressed in the rest of his oeuvre. Other great landscapists like Claude Lorrain digested what they found in nature in precisely the same way.37

Hessel Miedema, one of the foremost experts on Karel van Mander, agrees: “The oft-quoted passage about swallowing down and spitting out has to do with the talent of Bruegel, who stored up everything he had seen in his memory, assimilated it, and could subsequently use it ad libitum; this in contrast to the working from life of Jan de Hollander, which attracts low esteem and ridicule.”38 According to Miedema, van Mander distinguishes between Pieter Bruegel’s landscapes, and those of landscape artists like Jan de Hollander (or Jan de Amstel) of whom he gives an essentially negative account (despite referring to him as “highly distinguished”) in a passage tinged with irony.39 In his series of portraits of Flemish painters, published in Antwerp in 1572, Dominicus Lampsonius celebrates the landscapes (rura) of Jan de Amstel as “the glory of the Flemings,”40 while the Italians excel at the depiction of figures, hence the proverb asserting that “the Italians have their brains in their head, the Flemish in their skilled hands.” Coming from Lampsonius, this affirmation suggests parity between the genres rather than an acceptance of the inferiority of landscape.41 Van Mander takes the positive re-evaluation of landscape even further in his treatise, though he makes a distinction between two approaches to drawing from life (naer het leven): on the one hand, a nondiscriminatory record of reality, as adopted by Jan de Hollander, a painter disinclined to intensive study and tempted by the “easy option,” and on the other, a deliberate concern for the selection of natural elements, to be stored in the memory and sublimated by the painter’s intelligence or genius, a quality embodied by Pieter Bruegel better than any other.

Digestion as a Theory of Imitation

The “digestive” process of the “creative imitation” of nature and landscape—characteristic of Bruegel’s Alpine views—finds its exact parallel in the so-called theory of innutrition, in other words the assimilation—as opposed to the mechanical imitation—of literary sources, which focused contemporary attention on the status (in literature and poetry) of the vernacular, rather than Latin. Important heralds of this theory were Clément Marot, Montaigne, and Ronsard and the Pléiade writers in France, but also, in the Netherlands, Jan van der Noot and Lucas de Heere, to which Karel van Mander, himself a pupil of de Heere and a poet and classicist, was extremely close.42 Recently, Todd Richardson has written illuminatingly about the very close links that existed between the theories being developed in literary circles of the time, and Bruegel’s painting, which also insisted (as we have seen) on the development of a properly Dutch pictorial vocabulary. However, Richardson makes no connection between the theory of innutrition and the Bruegelian concept of the imitation of nature.43

The theory of innutrition is clearly articulated by the rhetorician Seneca in his letter no. 84 to Lucilius:

the food we have eaten, as long as it retains its original quality and floats in our stomachs as an undiluted mass, is a burden; but it passes into tissue and blood only when it has been changed from its original form. So it is with the food which nourishes our higher nature,—we should see to it that whatever we have absorbed should not be allowed to remain unchanged, or it will be no part of us. We must digest it; otherwise it will merely enter the memory and not the reasoning power. Let us loyally welcome such foods and make them our own, so that something that is one may be formed out of many elements, just as one number is formed of several elements whenever, by our reckoning, lesser sums, each different from the others, are brought together. This is what our mind should do: it should hide away all the materials by which it has been aided, and bring to light only what it has made of them.44

This theory, which dates back to Plato (the Symposium, Phaedrus), also appears in Quintilian45 and was taken up in the Renaissance by numerous authors such as Petrarch,46 Pietro Bembo,47 Montaigne,48 Rabelais,49 and Erasmus, who wrote:

That must be digested which you devour in varied daily reading, and must be made your own by meditation, rather than memorised or put into a book, so that your mind [ingenium] crammed with every kind of food, may give birth to a style which smells not of any flower, shrub or grass, but of your own native talent and feeling [indolem affectusque pectoris tui], so that he who reads may not recognise fragments culled from Cicero, but the reflection of a well-stored mind.50

Lastly, and above all, the doctrine was taken up by the poets of the Pléiade. It is articulated by Joachim du Bellay, for example, in the very specific context of La Deffence et Illustration de la Langue Francoyse (1549), in which the poet asserts the equal nobility of French, Latin, and Greek:

Immitant les meilleurs aucteurs Grecz, se transformant en eux, les devorant, & apres les avoir bien digerez, les convertissant en sang, & nourriture, se proposant, chacun selon son naturel & l’argument qu’il vouloit elire, le meilleur aucteur . . . Cela faisant (dy-je) les Romains ont baty tous ces beauz ecriz que nous louons et admirons fort.51

The metaphor of the digestion of sources draws in particular on the example of the bee sampling pollen from flowers, before transforming and digesting it into the delicious honey of poetry. Pindar, Plato, Seneca, Lucretius, Horace, and innumerable Renaissance authors used this comparison. In this way, as Teresa Chevrolet reminds us, “the imitation of nature shakes off its subjugation to the laws of realist reproduction, and in so doing confers upon the artist the dizzying power of a true demiurge.”52 Ronsard offers a particularly eloquent version, for our purposes, in his poem “L’Hylas,” substituting the landscape painter for the poet:

Mon Passerat, je resemble à l’Abeille

Qui va cueillant tantost la fleur vermeille,

Tantost la jaune : errant de pré en pré

Volle en la part qui plus luy vient à gré,

Contre l’Hyver amassant force vives:

Ainsy courant et fueilletant mes livres,

J’amasse, trie et choisis le plus beau,

Qu’en cent couleurs je peints en un tableau,

Tantost en l’autre: et maistre en ma peinture,

Sans me forcer j’imite la Nature.53

The same metaphor is found in other art treatises, notably Joachim von Sandrart’s Teutsche Academie, published in 1675, in which landscape holds a crucially important place—as it does in van Mander’s Schilder-boek. Sandrart’s eighth chapter, inspired by Horace,54 deals with the propriety to be demonstrated when representing figures, and cites the aforementioned example of the draftsman in a landscape:

In such depictions we must also take account of the figures’ profession and trade. A valiant swordsman or a spirited soldier will show different gestures and postures from a melancholy philosopher or a painter collecting the fruits of the tree of nature and swallowing them down so that he might spit them out, in a manner of speaking, on a sheet of paper or a piece of canvas [emphasis added].55

In his own biography—describing the drawings of antiquities he made in the Giustiniani gallery in Rome—Sandrart, too, compares himself to “a bee, thirsting after art . . . as if these were flowering bushes laden with nectar.”56 Samuel van Hoogstraten, in his Introduction to the Elevated School of Painting (1678), takes up the image of the draftsman in the landscape, when he talks of “gathering provisions,” which must subsequently be “extracted” from his mind, without mentioning digestion explicitly however:

Go then, O young painters! Into the forest, or up along the hills, to depict far vistas or richly wooded views; or to gather the abundance of nature in your sketchbook with pen and chalk. Go to, and try with steady observation to get used to never raising your gaze in vain; but as far as time and your tools permit, record everything as if you described in writing, and to imprint on your mind the character of things, so that you can draw on [this mental store] when you have no example from nature before you, with all this in your memory for you to use.57

The role of bodily ingestion in the process of imitation is not confined, in van Mander’s writing, to the Bruegel anecdote. It appears in at least two further passages in the Schilder-Boek. Van Mander explains that the painters Bartholomeus Spranger and Michiel Cocxie copied Roman antiquities in order to gather them into their “breast” (boesem). The image expresses the same idea of the artist appropriating or making “his own,” works of art which have served as his models:58

He [Cocxie] was also quick-spirited and was sharp at giving an apt reply or making a pungent remark. He was once invited to look at a large number of handsome sculptures and other work which a young painter had brought back from Rome; when the young painter complained at length about his shoulders because they had been so heavy to carry, he asked him if it would not have been easier to carry them in his breast rather than bodily, hurting his shoulders in this way. The other thought that the bundle was too large to be carried on his breast—but Cocxie meant in his heart or in his memory: that it would have been preferable if he had returned as a better master rather than to have overburdened himself with the work of other masters.59

In Den Grondt, Van Mander maintains that artists should absorb a model (inslorpen) if they want to imitate creatively (uit den gheest) rather than copy slavishly, using again the metaphor of digestion to discuss his theory of creative imitation. In his study on the relationship between Bruegel and Bosch, Matthijs Ilsink has directed attention to this passage, arguing that prints like the famous Big Fish Eat Little Fish (fig. 2), invented by Bruegel, but ascribed to Bosch, might be entirely concerned by this theme of aemulatio or assimilation of the style of a master by another painter.60

In Chapter 8 of Den Grondt (Van het Landtschap) van Mander expounds his optical approach to landscape painting, and uses another metaphor connected with food and ingestion. Van Mander is concerned above all with how to combine figures going about their daily occupations, with a vast landscape extending to a distant horizon, in the manner of the antique painter Ludius, or Studius, as described by Pliny the Elder.61 The painter must, he says, create “a small world” (cleyn Weerelt) in which the eye is free to roam and graze at will, satisfying its optical appetite. In this way, the picture’s viewers, “led by pleasure and desire, and hungry for more, . . . will peer over and under, like guests tasting many dishes.”62 In another chapter, van Mander praises the “licked” (polished) precision of Bruegel’s painting (Netticheydt), indicating that it provides “sweet nourishment for the eye.”63 In van Mander’s life of Jan and Hubert van Eyck, the art lover’s optical appetite for the beauty of a painted landscape is compared to that of “bees and flies in summer swarming and hanging around baskets of figs and raisins.”64

In this assimilation of eye and mouth, the theorist likens the painter’s panel to a table on which dishes are spread. The comparison links the Dutch words tafelreel (painter’s panel) and tafel (table); or the artist’s studio to a kitchen or dining room. This rich confusion of the senses finds its fullest expression in Dutch still-life painting, a generation later.65 The ancient Greeks made the same connection in their definition of the word parerga, originally used to describe landscape, but which some (like Philostratus) defined as condimenta picturae.66 Parerga is translatable as something akin to the French hors d’œuvre, taking further still the semantic interweaving central to any discussion of a “taste” for painting.

The Production and Expulsion of Images

Let us return to the apiarian origins of van Mander’s metaphor. Scientists have observed the bee’s regurgitation of honey since ancient Greek times. Pliny the Elder clearly writes in his Natural History that honey is “vomited by bees, out of their mouths.”67 Aristotle says the same in his History of Animals, explaining more precisely that bees ingurgitate the honey in order to spit or spew it out once they reach their destination.68 The bee’s digestive system transforms the nectar as it is swallowed and regurgitated several times over, before being stored in cells, inside the hive. For the ancients, honey—the product of successive ingurgitations and regurgitations—was quite literally bee-sick! This fact was well known in the Renaissance.69 Indeed, van Mander’s Schilder-Boek quotes the artist P. D. Cluyt, a skilled draftsman and trained physician, and his father Dirck Outgaertsz Cluyt (Theodore Clusius) (1546–1598), the celebrated director of the botanical garden in Leiden and author of the Natural History of Bees, published in 1597, which repeats the substance of the ancient authors’ writings.70

In his study of the bee in antique mythology, Jean-Pierre Albert notes that numerous sources and practices connect honey, and the production of honey, with the intestines. Hence the use of the word alvi (bellies) for hives, according to Varro, “for the food, the honey [they contain].” And he explains further: “it seems that the reason why they are so narrow in the middle is so that they may imitate the forms of bees [or: the form of an abdomen].” While Columella—after summarizing the technique of bugonia (the belief that bees were engendered by spontaneous generation from putrefying matter)—writes: “Magon even asserts that the same result may be obtained with the entrails [ventribus] of animals.” Pondering the frequency of these intestinal references, Albert reminds the reader that honey was widely held to be the excrement of bees: a paradoxical excrement, indeed, being edible, fragrant, and as pure as the creatures that produce it. Faced with these conflicting accounts, Columella advises his readers not to concern themselves with “whether bees vomit honey from the mouth or render it from out of some other part.”71

It is not our place to comment on these ancient beliefs here: suffice it to say that they may help interpret some odd details in Bruegel’s inventions (connecting beehives with arseholes and headless bodies; fig. 11) but also justify van Mander’s superficially repellent metaphor (and this to a hitherto unsuspected extent). From a more general, anthropological standpoint, they also reaffirm the role of the body and digestion in the process of the imitation of nature. As Jérémie Koering has written, of innutrition:

The body is the locus in which the immaterial, the subtle, the mutable and impalpable is transformed into matter. . . . The metaphor of ingestion and digestion . . . illustrates this continuity of the natural and imaginary world in which imitation, by engaging the body and its “organs” at the most fundamental level, maintains the materiality and living quality of the model in the object produced.72

In bees, honey (which Pliny believed originates in the heavens) is vomited or defecated. In Bruegel, the process of selecting the elements of nature and arranging them on canvas involves the artist’s own body. In van Mander’s image, swallowing is assimilated with seeing and drawing motifs from life, while regurgitation or defecation refers to the elaboration of new compositions in the artist’s studio—van Mander specifically indicates “upon returning home”—based on studies made ad vivum. Again, this reading is especially clear when compared with attitudes in contemporary literature. In Montaigne’s Essays, the humanist calls himself “a gentleman who only communicated his life by the workings of his belly” and he directly associates his oeuvre with excrement: “Here, but not so nauseous, are the excrements of an old mind, sometimes thick, sometimes thin, and always indigested.”73

The Figure of the Kakker in Bruegel’s Work

The rapprochement between digestion and ejection on the one hand, and imitation on the other, sheds new light on the recurring figure of the kakker (shitter) in the work of Bruegel and his Flemish contemporaries, and—it seems to me—on the figure’s hitherto overlooked theoretical dimension. As I have suggested elsewhere, the kakker may be understood as a satirical inversion of the figure of the draftsman in the landscape.74 To take one concrete example: in Bruegel’s Darmstadt painting, The Magpie on the Gallows, the kakker is situated in the bottom left-hand corner, in other words in the same prominent position as the figure of the draftsman in innumerable works from the fifteenth century onward (see fig. 6). Seen from behind, crouching down, he is the viewer’s point of entry into the composition.75 His hunched back defines a virtual line, extended farther into the picture by the raised arm of the man in red trousers, pointing to the splendid panorama that opens out on the horizon. This important diagonal—further reinforced by the crossbar at the top of the gallows—both opposes and connects the basest, most “material” and most spiritual aspects of the picture. In the exact middle of the canvas, and the diagonal line, the figure of the magpie is unmissable. The bird materializes the tension (so important in Bruegel’s work) between foreground and background, and the optical oscillation central to van Mander’s theory of landscape.76

The kakker plays an important role in Flemish painting. As van Mander also points out, Joachim Patinir habitually includes a small figure of a kakker as a kind of signature in his paintings, establishing a strong connection between the art of landscape and the grotesque: “He had the custom of painting a little man doing his business in all his landscapes and he was therefore known as “The Shitter.” Sometimes you had to search for this little shitter, as with the little owl of Hendrick met de Bles.”77 Michel Weemans notes, quite rightly, that this surprising association has its source in Pliny, and more specifically in the latter’s distinction between megalography (the painting of noble and elevated subjects) and rhyparography (the painting of commonplace, base subjects). For Patinir and Bruegel alike, it is clear that the antique landscape painter Studius (or Ludius), cited by van Mander as the model for the Flemish landscapists, is associated with the Plinian rhyparographers, thereby justifying Patinir’s initially rather strange-seeming signature.78

The role of the Bruegelian, rhyparographic kakker as a disruptive figure in an artistic system devoted to the preaching of ideal beauty (megalography) is explicit in another of van Mander’s anecdotes. In his life of the painter Hans Vredeman de Vries, the biographer reports that Bruegel had wickedly added a small detail to one of his colleague’s “perspective” paintings: “a peasant in a befouled shirt occupied with a peasant woman.” The painting’s owner laughed so hard on discovering the audacious detail that he refused to have it removed. Clearly, in Bruegel’s graffito, the grotesque and obscene serve to subvert the Romanizing architecture of Vredeman de Vries, who was known at the time as the “Flemish Vitruvius,” though the amused owner’s attitude to the “very spiritual” Bruegel was anything but severe.79

Digestio—Dispositio—Ordinanty

Interpreted from an artistic standpoint, van Mander’s anecdote describes a practice favored by the majority of Renaissance landscape painters—a practice that finds its highest expression in the work of Claude Lorrain, as Konrad Oberhuber rightly points out in the passage quoted above: the artist draws out of doors before returning to his studio to paint imaginary landscapes, the fruits of his ingenium, based on his sketches.80 This is an important remark for the history of landscape painting, since the Flemish tradition of landscape painting defined as “realistic” has been exaggeratedly contrasted with the “ideal” landscape of the Italians in the historiography of the field, starting with Michelangelo’s famous critique of Flemish art referred to by Francisco de Hollanda.

In this context, it is symptomatic that the term digestio, as used by Cicero or Quintilian, for example, also refers to a rhetorical device enacting the distinction between a general idea and specific points or chapters—in short, the process of ordering (ordo, ordinatio).81 In this, it is similar to another rhetorical device, namely dispositio.82 Transposed to painting, the term is applicable to the forging of a harmonious composition from heterogeneous fragments (ordinanty in van Mander’s terminology).83 As such, the word eloquently describes one of the central preoccupations of landscape painters from Bruegel onward. Van Mander also uses the term stellingh, originally applied to the disposition of figures in history painting, to describe Bruegel’s arrangement of the elements of his Alpine landscapes. He writes:

Besides I could proclaim proudly the fine coloring and artful disposition of the works and prints of the counterfeiter Bruegel, in which, as if we were in the horn-capped Alps, he shows us how without great toil we may fashion views deep into vertiginous dales, [then up toward] steep cliffs and cloud-kissing pines, [then out toward] far distances, and along rushing streams.84

Epilogue: Doctor Rabelais and the Mind-Body Dialectic

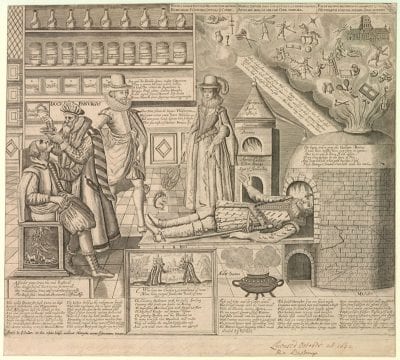

From a more general cultural standpoint, the central importance of the digestive metaphor in Bruegel’s and van Mander’s day (and Seneca’s, long before)85 is directly linked to medical knowledge and, more specifically, to the theory of the humors, according to which the body and spirit or disposition are governed by the same qualities (hot, cold, dry, wet) and elements (earth, air, fire, water). For example, melancholy—diagnosed as an excess of black bile—could be caused by “poorly digested” images.86 An engraving by Matthaus Greuter, republished several times, is described as showing “a doctor [purging] a melancholic by causing him to defecate his images” (fig. 12).87 The idea seems to have been current before the Renaissance: the Expositio prosae de Angelis, by the twelfth-century writer Alain de Lille explains that “images are defecated by the mind.”88

These scatological metaphors refer to actual therapeutic practices of the time, based on the use and abuse of intestinal purges and forced vomiting, in order to free the mind or spirit. Galen of Pergamon and Hippocrates were the sources for the practice, cited in numerous medical texts. The virtues of vomiting are celebrated in Aldobrandino of Siena’s Régime du corps (Regimen of the body, 1256), which also notes the best times of year for bleeding and intestinal purges. An entire chapter is devoted to purges, followed by another on vomiting: “Par coi il fait bon user le vomir”—advice doubtless followed by Rabelais for the healing of his invalid Pantagruel.89 A later English version of Greuter’s image in the British Museum depicts this medical world (fig. 13). The toilet chair is reserved for a peasant figure (a rude Rusticall), while a young courtier and clerics receive other treatments for the expurgation of corrupting images from their minds. Here, the association of the peasant figure with scatology echoes the Bruegelian strategy highlighted by van Mander in his biography: the peasant regurgitates or defecates his images. Dated circa 1600, the engraving’s first edition is derived from an emblem in Theodor de Bry’s Emblemata Saecularia of 1597, a work that borrows several figures of drunken peasants from compositions by Karel van Mander.90 Interestingly, in Martin Droeshout’s version of the print (circa 1620–30), the doctor is renamed Panurgus, indicating a close kinship with the world of Rabelais.91

The conjunction of medical science, food or nourishment, obscenity, imitation, and satire is indeed (especially) dense in Rabelais,92 himself a doctor, whose writings were often justly compared to Bruegel’s paintings. The rapprochement has a long history. In 1565, a collection of engravings entitled Les songes drolatiques de Pantagruel includes six plates directly inspired by characters and motifs from the series of Vices published by Hieronymus Cock in 1558.93 In Rabelais, as in Bruegel, the representation of imitatio as digestio is more than a straightforward scholarly reference disguised in burlesque tones. It affirms the central importance of the body in the construction and perception of the text or image. Michel Jeanneret’s comments on Rabelais’s assimilation of imitation and digestion are worth noting if we are to understand the paradoxical hermeneutics in Bruegel, as articulated by van Mander:

It would be wrong—he writes—to take this bibliophagy lightly and to neutralize its power by shelving it as cliché and rhetoric. The comic surface belies a profound reflection on the status of literature in the experience of everyday life. We understand it better in its cultural context. The oral tradition, or what remains of it when our mentalities and mores are dominated by print; the written document is rarely dissociated from its enunciation in the spoken word. In such circumstances, the word is perceived as an audible presence, an articulation, an accentuation, the sender’s physical engagement in his message. The text is addressed not only to the intellect; it is a global event that demands the participation of body and mind alike. Communication is perceived as a series of concrete impulses and abstract significations alike, an aspect of organic life impacting the whole person. And the same is true of knowledge, which remains associated with an act of sensory apprehension. To acquire learning is to transport a tangible object from the outer to the inner world.94

Like Bruegel’s oeuvre, Rabelais’s writing perfectly encapsulates this dialectic of the internal and external, inner and outer, essence and appearance. As such, it constitutes—with the writings of other humanists like Erasmus—a crucial source for our understanding of the driving forces behind Bruegel’s art. As Bakhtine has clearly shown, defecation is a powerful metaphor for birth and rebirth, creation and intellectual creativity, especially in Gargantua—remember, for example, the episode of Gargamelle giving birth, or the infant Gargantua hunting for the best arse-wipe.95 Similarly, in Bruegel’s Magpie on the Gallows, the opposition between the kakker in the foreground—like so many figures of draftsmen in landscape paintings—and the splendid natural panorama establishes a pictorial tension that invites us to read beyond our initial apprehension of the grotesque, ludicrous detail (see fig. 6). Just as van Mander establishes a paradoxical link between Bruegel’s regurgitation and the “intelligent” imitation of nature, so Bruegel himself juxtaposes an ideal landscape and a figure attending to the basest of human needs, inviting us to read the composition on a number of levels. Voltaire shows a clear understanding of this “Silenic” aesthetic when he writes, in Rabelais’s own voice: “I took my compatriots at their weakest point; I spoke of drinking, I talked filth, and with that secret, I was afforded every liberty. High-minded people heard finesse, and were grateful to me; coarse folk saw only filth, and relished it: far from suffering persecution, I was loved by all.”96