Like Rembrandt, Gerard de Lairesse never visited Italy. But whereas, for Rembrandt, this failing did not matter greatly, given that he was forging a distinctive, individual manner, Lairesse was trying to follow in the footsteps of artists, such as Raphael, Poussin, Carracci, and Domenichino, whose work he had never seen. The artist often characterized as “the Dutch Raphael” or “the Dutch Poussin” only knew the works of Raphael and Poussin through prints. In this paper I examine how this vicarious knowledge of “the grand manner” influenced Lairesse’s own pictorial style, focusing in particular on his theory and practice of color.

For a man with such a cosmopolitan view of art, Gerard de Lairesse seems to have traveled remarkably little. We have no evidence that he ever visited Italy,1 or France, or Spain, or England. He did it seems once travel to Cologne, and there is an unsubstantiated claim that he may have paid a brief visit to Berlin; but apart from these excursions into Germany, his life seems to have been spent almost entirely in two towns, Liège and Amsterdam.2

In this, of course, he was not unlike his older contemporary Rembrandt, who saw even less of the world than Lairesse. However, for Rembrandt travel was hardly necessary, since the style of painting he developed owed little to the work of painters from outside the Netherlands. Lairesse could not make the same claim, since he wanted to paint in the grand manner of Raphael, Carracci, Domenichino, Poussin, and Le Brun, the idealizing style of history painting founded on the study of antique sculpture.3 And yet seeing pictures made by these artists cannot have been easy for Lairesse, since in his day their works were thin on the ground in the Dutch Republic. We know of course that Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione passed through the Amsterdam art trade, and that Rembrandt saw it and sketched it as it went by.4 There are, too, a number of other paintings assigned to Raphael, or said to be copies after his work, which are traceable in inventories and sales catalogues. Two were said to be “tronies”: one wonders which paintings by Raphael would have been given this description.5 Another was said to be a Venus, another a Judith; the second of these was a copy and valued at 36 guilders; the first was valued at 26 guilders and so must have been a copy too.6 A Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness may have been a copy of the Raphael School painting that has been hanging in the Tribuna in the Uffizi since 1589.7 And finally there is a “Maria beeltie” in Rembrandt’s bankruptcy inventory.8 Raphael did of course paint numerous small Mary images, but whether Rembrandt’s example was an original, a workshop production, a copy, or a fake we may never know—and, of course, we are still arguing about the attribution of peripheral Raphaels today.9

If Raphael provides us with thin pickings in seventeenth-century Dutch collections, the same is true for the other artists Lairesse admired greatly. In the Northern Netherlands for the seventeenth century the Getty Provenance Index and the Montias Database list four Carraccis—whether Ludovico, Annibale, or Agostino is unmentioned;10 three landscapes by Poussin—whether Nicolas or Gaspard is unmentioned;11 one Domenichino;12 and no Le Bruns. To these pictures can be added a painting of Jacob and Rachel (or Rebecca and Eleazar) said to be by Poussin (Nicolas or Gaspard) in the Six collection13 and a cycle of the Seven Works of Mercy attributed to Annibale Carracci, which according to Sandrart could be seen in the home of the Coymans family in Amsterdam.14 By the turn of the eighteenth century there were more Italian and French works in the Netherlands—in particular, the Rotterdam merchant Jacques Meyers put together one of the greatest collections of Poussins ever assembled—but Lairesse lost his eyesight in 1690, and there is no evidence that he knew the pictures on Meyers’s walls, nor indeed of any of the other paintings we have just listed.15

It is then perfectly possible that Gerard de Lairesse, who has often been called the Dutch Raphael and/or the Dutch Poussin,16 had never seen a genuine Raphael or Poussin. He may have thought that he had seen a Raphael or a Poussin—he may have been taken in by a wrong attribution or a deliberate forgery. But if so, he does not recount the experience in his Groot Schilderboek. Whenever he refers to specific Raphaels or Poussins, he is referring to paintings that he cannot have seen, since they were hanging on, or cemented to, walls in Italy and France. What he knew were not the paintings themselves, but reproductive prints after those paintings.

As an example of this, take a passage in the Groot Schilderboek, in which he writes in favor of what he calls “kloeke beelden,” “robust figures,” as Lyckle de Vries has translated it.17 Painting robustly, Lairesse tells us, is to paint the figures so that they look large, as if they were seen close by, rather than small, as if they were seen in the middle distance.18 In his chapter defending robust figures, Lairesse gives examples of Italian and French paintings that are painted in the robust manner:

Consider for example the Woman at the Well, by Carracci;19 Simon the Magician, by Raphael;20 Judith, Sheba, Esther and David, by Domenichino;21 Esther and Ahasuerus, by Poussin.22 Look at the beautiful piece by Le Brun, depicting the Death of St Stephen:23 how he has arranged these things with wonderful power, skill and naturalness, and also with robust figures. This example is enough to show clearly that painting robustly far surpasses painting on a small scale, and that whoever is practiced at painting on a large scale, can descend without difficulty to the small-scale, should he so desire: but that on the other hand someone who always remains busy with the small-scale, can attain the large-scale only with difficulty.24

From this it sounds as if Lairesse has seen the paintings themselves; but since only one of these pictures was in the Low Countries during his lifetime, he must have known the others through prints.25 The exception to the rule was Annibale Carracci’s Woman at the Well (Christ and the Samaritan Woman), which was in the collection of Jan Six in Amsterdam from at least 1669.26 It is possible that Lairesse saw this painting, but if he did, he does not mention the fact, whereas he does claim to have seen three prints after the painting.27

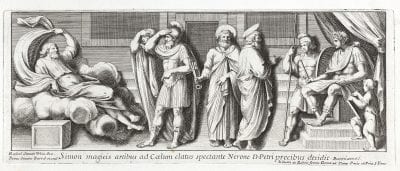

Throughout his chapter on robust painting, Lairesse compares painting robustly with painting large or life-size figures, to the extent that his early English translators actually rendered “kloek” as “large.”28 That was a reasonable confusion, since Lairesse himself seemed to assume that anyone who was painting robustly would also be painting on a large scale, an attitude that is implicit in the quotation above. And yet it is of course possible to paint robust figures on a small scale, as we can see if we consider Raphael’s fresco of Simon the Magician. This is not one of Raphael’s better-known works, even though it is in fact in the Raphael Stanze, in the Stanza dell’Incendio. However, it is located in a corner of the room where few of us ever direct our gaze, in a window embrasure next to the Coronation of Charlemagne (fig. 1). This frieze is probably not by Raphael himself, but by someone in his workshop, who may have been following a sketch by the master. Lairesse must have known it from the print in one of Pietro Santi Bartoli’s series of etchings after Raphael’s marginal designs (fig. 2).29

Lairesse discusses this frieze of Simon Magus as if it were a large painting with large figures, and presumably he imagined that it was. The image is robust, in that the figures are viewed from close by; but it can hardly be called large—certainly not in comparison to the fresco next to it. This brings home the extent to which Italian art was, for Lairesse, a matter of imagination, indeed of fantasy. Looking at this small, rather undistinguished print, he conjured up in his mind a huge painting with grand figures, of the kind that Raphael did of course paint in other places—for example, on other walls of the papal Stanze. Some Dutch colleague who had been to Rome must have told Lairesse about the life-size scale of Raphael’s frescoes, and as a result he assumed that a print after a design by Raphael must be recording a whole wall full of artistry.

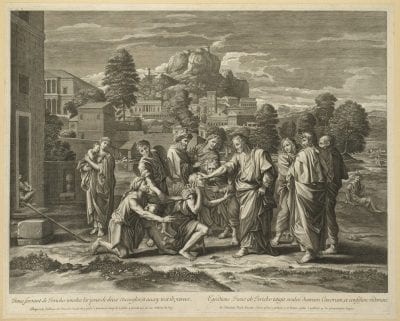

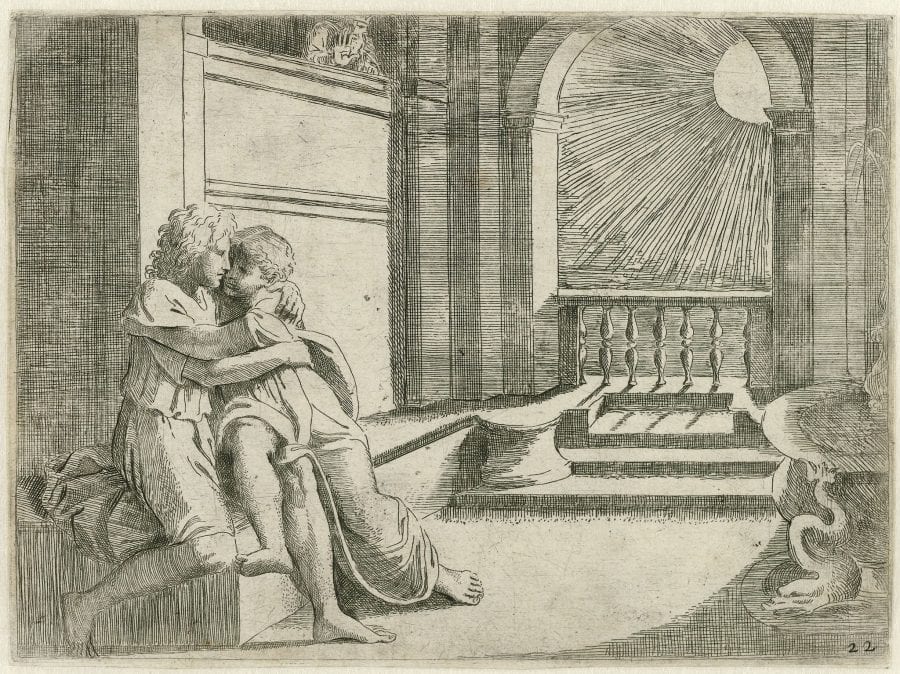

The passage we have been considering gives the uncautious reader the impression that Lairesse had firsthand experience of all the paintings in question, but in other places he is perfectly open and unapologetic about the fact that he is looking at prints. He refers a number of times to Raphael’s Bible prints, which he probably knew from the series etched by Sisto Badalocchio and Giovanni Lanfranco.30 These are printed versions of the compositions that Raphael and his workshop painted in the Vatican Logge. Although the Raphael Bible, as it is known, is a record of Raphael’s frescoes made over eighty years after Raphael’s death, Lairesse seems to have been unaware of the fact, and in one passage even gives the impression that he believed Raphael could have made the etchings himself. After making criticisms of two prints, of Abimelech seeing Isaac and Rebecca caressing (fig. 3) and of David seeing Bathsheba bathing, he goes on to write:

But since the greatest masters have their bad days, it seems probable either that these Bible prints were made in his earlier period, or that in his later period they were drawn or painted after his rapid sketches by his best disciples such as Giulio Romano, Gianfrancesco Penni or Perino del Vaga, and then retouched by Raphael himself.31

If we are to take this passage literally then it would appear Lairesse thought Raphael might have made these etchings himself when a young man, or toward the end of his career allowed his pupils to work them up from his sketches, to which he gave the finishing touches.32 It could be that he is compressing too much meaning into his sentence, and that when he spoke of Bible prints he meant the frescoes of which these Bible prints were copies—the fact that he used the word “geschilderd” perhaps suggests as much.33 But if he did muddle up prints and frescoes in his mind, that would be a revealing confusion, since Lairesse’s response to Raphael was derived from etchings and engravings like these. For him, the etched copies of these paintings were as close to the original frescoes as he managed to get.

And, as with the example of Simon Magus, the jump from etching to painting was not always easy to make. Consider for example what he says about the print of Abimelech seeing Isaac and Rebecca caressing, a subject that he misidentifies as Abimelech seeing Abraham and Sarah caressing. The story from Genesis is that Isaac and his wife Rebecca had come to live in the kingdom of Gerar, ruled by Abimelech. Fearing that the inhabitants of Gerar might kill him for his beautiful wife, Isaac pretended that Rebecca was his sister. When the king saw them caressing, he realized that Isaac had been lying to him.34 Lairesse tells us that he does not like this composition—that it reminds him of mistakes he made in some of his own juvenilia. He is troubled by the bright sun shining through the arch. Trying to think of the reason why Raphael would have wanted to depict so fiery a sun, he suggests that, if the sun had not been shining directly on the couple, then Abimelech might not have been able to see them, given his distant position.35 These ruminations are typical of Lairesse’s analyses of compositions; he usually tries to find some logical explanation for the arrangement of the figures. In fact, in this particular instance he is not far from the truth, and he would have grasped it, if he had been able to see the colors of the painting, and so realized that the scene is suffused with the golden light and deep shadows of a sunset (fig. 4).36 Once we have understood the time of day, the shadows look as if cast by a setting sun—this is the case, it seems to me, even in the print.37 Now we can see why it was necessary to represent the sun shining through the arch; without the last rays of the sun, Abimelech really would not have been able to see the loving pair—in the twilight. Distance, of course, has nothing to do with it: Abimelech is only about two meters away from the couple.

The biblical passage of which this is a translation does not mention the time of day. The decision to turn it into a sunset was Raphael’s—or Giulio Romano’s or Gianfrancesco Penni’s or Perino del Vaga’s, the attribution is disputed.38 There are good, rational reasons for the setting at dusk, ones of which Lairesse would surely have approved. If Isaac and Rebecca were keeping their married state a secret then they were more likely to embrace in failing light. But there is, too, another reason for choosing this setting, one which the logical Lairesse might not have been so quick to appreciate. Paintings, or at least successful, moving paintings, are rather more than the clear and consistent depiction of narratives. They are also visual poems, in which all the elements combine to create and convey a mood and an experience. Even in its damaged state, this fresco is an alluring evocation of love at the end of day. Everything comes together in a mysterious unison: the couple, their legs entwined; the shadows cast by the sunset; the balcony through which trees and evening sky can still be seen; the soft shapes of the palace architecture; the fountain with its plashing water.

Not much of the magical power of the original fresco survives in the Badalocchio print, it must be said. And that, perhaps, is why Lairesse’s conception of what makes a good composition so frequently boils down to the rational arrangement of elements within the logic of the narrative. This is a man, after all, who wrote that, although he was blind, he could compose a painting as well as someone with sight;39 because, he tells us, “the most important thing to bear in mind when composing a picture is probability.”40 For someone with such a functional concept of composition, the poetic power of art is an irrelevance. But perhaps it would have become more relevant to Lairesse if he had seen more actual paintings, and fewer poor engravings, which gave no more than a faint flavor of their originals.

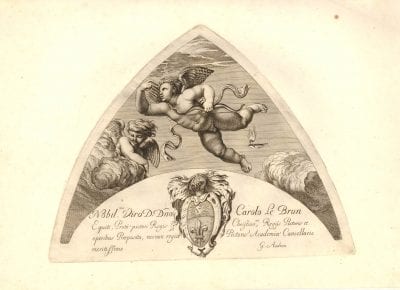

Lairesse was aware of the fact that prints varied in quality, but even high quality prints could mislead him. He had a great admiration for the work of the French engraver Gérard Audran41 and must therefore have put particular trust in his engravings of amoretti from the lunettes of Raphael’s Cupid and Psyche ceiling in the Villa Farnesina. These Farnesina putti attracted Lairesse’s criticism, since he felt that they were too muscular.42 He may have been thinking in particular of this one (fig. 5), with his burly thighs and shoulders and protuberant stomach muscles. Lairesse directs his criticism not at Audran, but at Raphael, assuming that Audran’s prints can be taken as a trustworthy rendition of the original frescoes. However, if we compare the print to the original (fig. 6) we can see that Raphael’s putto is several kilograms lighter than Audran’s, with much less developed musculature. Lairesse has drawn conclusions about Raphael’s art from Audran’s engraving, and once again it turns out that his conclusions were unwarranted.

Lairesse tells us that Raphael is the greatest of painters,43 but his opinion on the matter seems to be based almost entirely on his trust in the general consensus. As far as we can tell from his discussions in the Groot Schilderboek, Raphael’s art was known to him from a fairly small number of mostly undistinguished etchings and engravings. Besides the cycles we have already considered, the only work by Raphael to which Lairesse refers in his treatise is Marcantonio’s engraving of the Fall of Man (fig. 7), which he criticizes for “a coarse mistake,” the fact that there is a sawn-off branch at a time before the invention of saws.44 Looking through the prints Lairesse knew, one wonders how his imagination could ever have been fired by Raphael’s art, and one wonders, too, what he would have thought if he had traveled to Rome and seen Raphael’s most famous paintings, in color, with all their delicacy of tint and touch. Perhaps he would then have thought that composing pictures was not a task that could be carried out by the blind; that it involved rather more than arranging figures to bring about the maximum narrative probability. Lairesse believed that good art follows clear rational rules, but perhaps he would have been less sure of that if he had experienced more of the art he said that he admired, in all its complexity and power.

When it came to the art of Poussin, Lairesse had an advantage, in that the quality of the prints available to him was much greater. No artists in European history have been better served by reproductive printmakers than Nicolas Poussin and Charles Le Brun, and their good fortune was of course assisted by a government arts policy that used etched copies of French works as a means of convincing Europe that the France of Louis XIV was an artistic, as well as a political and military great power.45 Lairesse was a firm admirer of French prints, and he singled out Gérard Audran,46 Gérard Edelinck,47 Cornelis Vermeulen,48 and Michel Natalis49 for particular praise.

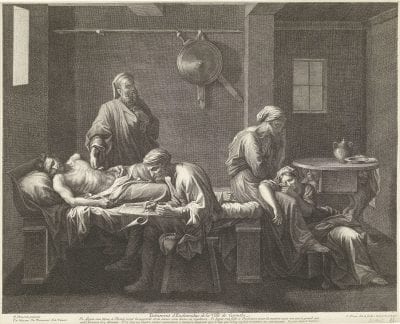

These prints were so sophisticated and seemingly accurate that they allowed him to make remarks about subtle effects of light and shade. Take for example his comments on Poussin’s Testament of Eudamidas (fig. 8).50 The obscure story, from Lucian’s dialogue Toxaris, concerns a poor soldier who had nothing to leave his friends in his will except his wife and sister, with the request that they be taken care of. Since his wishes were obeyed without question, the story is recounted by Lucian as a moral exemplar of friendship.51 Lairesse misidentifies the subject as the death of the Theban general Epaminondas, but it is not really the subject that concerns him; what he is interested in is the light. He writes: “No rule concerning light was neglected in this work. Everything has its natural effect, so that it appears enchanting and charming to our eyes.”52 In the margin he adds “Fine print by N. Poussin”;53 the painting was in a French private collection at this time.54 The question is whether the subtle effects that he saw in the print are also there in the original by Poussin (fig. 9). This is not easy to say, since the painting, like many of Poussin’s works, has darkened.55 The print seems to contain a variety of light fall, which is now absent in the painting. Consider, for example, the head of the mother of Eudamidas. In the print this is illuminated with a number of glancing and delicate reflections, but in the painting the effect is much more uniform. That may well be because the highlights have faded, perhaps because areas of lead white have become translucent. Another possibility is that the engraver increased the effect of reflection, since reflections in shadows came more into fashion among artists as the seventeenth century progressed.56 But whatever the truth of the matter, Lairesse’s praise was elicited by the print, not the painting; he had not seen the Poussin itself.

Another remark praising Poussin’s use of light can be found in Lairesse’s brief mention of Christ healing the blind of Jericho (fig. 10). Lairesse writes that:

one should take particular care to ensure . . . that the light falls on the most important object and place, as Poussin correctly showed in a painting where he depicted Christ giving back sight to the blind; where the greatest and most forceful light is entirely spread over him.57

Again, Lairesse cannot have seen the original, which was in the French royal collection; he must have been thinking of a print, quite possibly the one by Guillaume Chasteau (fig. 11).58

What exactly did he mean by “the largest and most forceful light” (“het grootste en krachtigste licht”)? If he meant the lit part of the painting that has the most powerful visual impact, then the Apostle in yellow at right or the blind man in the cream-colored tunic at left seem just as striking. Again, we have to be careful with respect to pictorial condition; the balance of color in any painting, but especially a Poussin—even a Poussin in unusually good condition such as this one—can change quite considerably over time. But this is hardly relevant in this case, since Lairesse cannot have seen the painting itself; he was thinking about the print, where, without the distraction of color, we might agree that the light on Christ is the largest and most conspicuous. It is indeed possible that the print better preserves the original balance of light than the current state of the painting. There is a smooth evenness of light in the Chasteau, which creates a greater spatial coherence, and one can I think argue that this coherence was present in the original Poussin but has been distorted as the painting has aged.

As well as studying and admiring these prints, Lairesse also made use of them as an artist, picking up ideas both for figures and for compositions. It is interesting to watch his practice in this, since he never slavishly follows his models but rather uses them as inspiration for new compositions. At the same time, one can often sense, so to speak, the print he is using, and one can see as well that he is following the print and not the painting. As an example, consider Lairesse’s painting of the death of Germanicus (fig. 12). This has clearly grown out of a careful and appreciative perusal of Guillaume Chasteau’s print after Poussin’s Germanicus (fig. 13).59 Lairesse had not seen the original painting, which was in the Barberini collection in Rome; and that he is looking at the print we can deduce from the way he builds his composition around the dying Germanicus on the left, rather than the right, of the composition.60 No detail is the same between the painting and the print, each pose has been rethought, and the cast of characters, too, has been altered significantly. And yet there are at the same time clear resemblances; consider for example the soldier raising his sword—which has been moved from his left to his right hand, quietly correcting the inversion of the print—or the nurse holding a child, who Lairesse has merged into the figure of the weeping Agrippina, Germanicus’s wife. And then, too, there is the pose of Germanicus, straining to look to one side; as well as the draperies over the bed and the architectural view leading off to the right. It is interesting to follow Lairesse as he remolds his sources in this way.

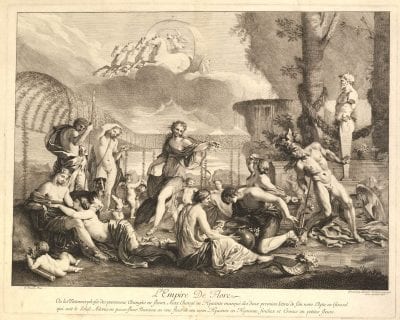

Another example of the same phenomenon is his reaction to Poussin’s Empire of Flora. The whereabouts of this painting during Lairesse’s lifetime is not currently known, but there is no reason to suppose it was in the Northern Netherlands, and in any case he tells us in the Groot Schilderboek that he knew it through a print, probably the print by Gérard Audran (fig. 14).61 We can perhaps also deduce that the copy of the print that Lairesse knew had been shorn of its explanatory motto along the lower edge, since he declared himself thoroughly baffled by the subject. The Empire of Flora is a collection of mythological individuals all of whom have given their names to flowers, such as Narcissus, Hyacinth, and Crocus. Ajax is the exception, since he did not have a flower named after him; but when he stabbed himself, Ovid tells us, a hyacinth flower grew up at the spot where his blood struck the ground.62 All of this is explained in the motto to Audran’s engraving, but Lairesse could not understand the iconography. He thought that the print represented the Elysian Fields and was shocked to see Ajax committing suicide in such a hallowed spot. “I find it hard to believe,” he wrote, “that Poussin himself could have thought up such a strange conception; for he places Ajax among the blessed in so cruel a posture; a man who, as a murderer of himself, should rather have earned a place in hell.”63

Nevertheless, if he disapproved of the subject, Lairesse must have admired the print, since he made use of it when painting his Bacchanal in Kassel (fig. 15).64 Although the subject is very different from the Empire of Flora, even from Lairesse’s conception of the Empire of Flora, there are a number of quotations and half-quotations of Poussin’s composition. The figure of Bacchus, for example, seems to be based on the figures of Hyacinth and Adonis in Audran’s print; Lairesse has given Hyacinth the right arm of Adonis. Then, too, the young man looking into the wine vat in the left foreground of Lairesse’s painting resembles Narcissus gazing at his reflection in the Poussin. The figure of Ajax may have met with Lairesse’s disapproval, but he seems to have liked the shape of its right leg, since he used it for the young bacchant in the right foreground. And Poussin’s herm of Pan is reused in disguised form in the Lairesse. Note, too, the echoes in the overall composition, with the herm, the trees, and the fountain in the print echoed by the herm, the trees, and the urn in the painting. It hardly needs saying that all of these resemblances are configured in accordance with the print, which reverses the composition of the painting.

Lairesse drew on Poussin for inspiration and may even have seen himself as a follower of the Frenchman. And yet once we compare not Lairesse to Poussin prints but Lairesse to Poussin paintings, we can see that what similarities there are between the two artists are confined to choice of motifs and style of drawing. A profound difference, on the other hand, comes with their use of color. For Lairesse, color should always be subservient to verisimilitude. As he himself put it:

although Nature is deficient in all other branches of Art, she is not in so far as concerns Coloring, and this is why, in this branch of art, no better model has been found than the life itself; that also, whatever does not perfectly agree with it, however much it may charm and please the eye, remains in itself false and of no worth.65

This is a doctrine of coloring to which any number of Dutch genre, landscape, and still-life painters might also have subscribed. Poussin, too, might have paid lip service to this ideal, but at the same time he was aware that color played a crucial role in creating the distilled mood of a painting. As his friend and biographer André Félibien observed:

M. Poussin represented his Figures with actions more or less strong and colours more or less lively, depending on the subject which he was treating . . . When he represented a sad and lugubrious subject like the Plague (fig. 16), all the colours were muted and half faded . . . But in the subject of Rebecca (fig. 17) which has to be full of grace, he only employed lively colors, which he gently broke into one another, and which made a blend that charms the eyes.66

The condition of these two works is far from perfect; both have been transferred to new canvasses and have darkened as a result.67 But even with these paintings in poor condition we can see that Félibien has a point; Poussin does vary his color depending on the theme and uses both color and handling for expressive purposes.

These remarks come in the midst of a passage in which Félibien explains Poussin’s concept of the modes, the idea that paintings, like music, should be constructed around an emotional theme, of joy or violence or fear or sadness, which all the elements of the painting should combine to express. Poussin put forward this theory of the modes in a famous letter to Paul Fréart de Chantelou, and while in that letter he did not mention color as one of the elements of expression, Charles Le Brun and André Félibien, who both knew him well, both asserted that color was of importance to Poussin’s modal practice.68 There has been much debate about what Poussin meant and how it impinged on his painting. But if we return to Lairesse’s Death of Germanicus, and this time compare it not to Chasteau’s print but to Poussin’s painting (fig. 18),69 we can perhaps get some idea of the difference of approach between the two painter-theorists. Poussin uses intense reds, yellows, and blues to create vibrant contrasts, which have no very obvious spatial function, but which by their violence add to the dramatic mood. Germanicus was poisoned by the governor of Syria, possibly acting on the orders of the emperor Tiberius, and here we see the mourning of his family and friends and the eager desire of his fellow soldiers to avenge his death. Poussin’s colors have been carefully chosen to evoke the powerful and tragic emotions of the event. Lairesse on the other hand uses a more broken palette, aiming for a muted effect in which spatial relations are registered with subtle distinctions of tone. In this, he is certainly successful; he is, it seems to me, much better able to create a sense of houding than Poussin, even taking into account the dubious condition of most of the latter’s works.70 But if he creates space effectively, he does not put color to the service of expression, in the way that Poussin did.

It is of course hardly surprising that Lairesse, who learned so much from Poussin, should have taken less from the latter’s practice when it came to coloring: he had probably never seen a real painting by the Frenchman. He could study drawing, expression, and composition from prints, but not coloring, and for this he drew on the standard practices of Dutch painters of his day.71 That is why, of all the chapters of the Groot Schilderboek, the chapters on color are the most precious, as a record of Dutch painting. Lairesse may have been an admirer of the Italianate Grand Manner, but as a theorist and practitioner of coloring, he was closer to Jan Steen than to Poussin or Raphael.72