This article demonstrates how Lairesse’s style, his knowledge of contemporary Italian art and ideas, and his understanding of the art of antiquity was fully developed by 1670 and had been shaped by the Romanist-classicist tradition in Liège and through confrontation with the art in Amsterdam, without any significant intervention of French painting and art theory.

In the second half of the nineteenth century a positive view of seventeenth-century Dutch art (realist, honest, the art of the common people) came to oppose a negative view of French art (idealized, academic, aristocratic) of the same period.1 Dutch painting of the later seventeenth century was therefore perceived as ruined by the French influence, and Gerard de Lairesse, who functioned within this framework as the epitome of “Frenchness,” became the scapegoat. Over the last decades the explicitly negative connotations of this “Frenchness” have diminished considerably, but the notion that his paintings and theories were “French” has remained with us ever since and is prominent in characterizations of Lairesse’s oeuvre in surveys of Dutch art.2 Lairesse was, for example, the “principal Dutch advocate of the classical doctrine that was spreading over Europe from the French Royal Academy,” wrote Rudi Fuchs in 2003 in his concise book on painting in the Netherlands, as he judged Lairesse’s paintings “typical of the French influenced phase of Dutch painting.”3 Some authors have recently qualified this notion of Lairesse representing French art and art theory in Holland and have drawn attention to the Netherlandish context of his achievements as artist and author,4 but only Melinda Vander Ploeg Fallon, in a valuable American dissertation, has tried to undermine the idea that Lairesse’s art was “French.”5 The German art historian Ekkehard Mai, by contrast, has argued quite radically for Lairesse’s orientation toward French classicism and art theory.6 Most francophone art historians also lay claim to Lairesse as part of a specifically French sphere of influence.7 Alain Roy, the author of the only monograph on Lairesse with a catalogue raisonné, maintained that the painter was: “un artiste de culture française, formé dans le gout français, et que ses préférences et matière de théorie le portaient tout naturellement vers les écrits français.”8

But was Lairesse, in fact, strongly influenced by French painting and French art theory? Or, to formulate it in more active terms, did Lairesse see French painting and French art theory as the primary examples to follow? And would Lairesse himself, as well as his knowledgeable contemporaries, have considered his works of art and his artistic ideas as rooted in French art and theory? And if this is not the case—a position I will argue in this essay—how should we situate his work?

Lairesse’s “Frenchness”

It is worth noting that no seventeenth- or eighteenth-century author connected Lairesse’s work directly with French art and theory.9 The only instances where France and a French painter turn up are in Joachim von Sandrart’s entry on Lairesse in his first edition of the Teutsche Academie (1675), where Sandrart wrote that Lairesse came from France to Holland and seemed to be a follower of Sebastien Bourdon, and in a letter by Philip Tideman, a pupil of Lairesse. Tideman observed about an early work from Lairesse’s Liège period that “it had much in common with the work of Poussin.” Sandrart’s remark was, however, a mistake that he would soon correct in the Latin edition (1683).10 In 1675, Sandrart obviously knew nothing about Lairesse’s origins. He made up for this in his well-informed revised biography in Latin eight years later; by that time, he must have received more accurate information from people who were close to Lairesse. In the revised biography, he referred instead to Lairesse’s great admiration for antiquity and Italian art. I will return later to Tideman’s observation. Suffice it to say that Poussin was not yet seen as an exponent of French art; his work was entirely associated with the artistic scene of Rome and the classicist tradition in Italian art.11 Lairesse held to this view as well. Lairesse’s first biographers, authors who knew him well (Louis Abry) or were acquainted with other artists who had been in personal contact with the master (Sandrart and Arnold Houbraken), make no mention of any French connection. The only “foreign” references in their discussions of his life and work are invariably to Italian art.12

And indeed, when praising Lairesse highly, these authors had little reason to refer to French art and ideas. Nor would Lairesse have reason to present his art as “French,” if only because such a categorization would not have contributed to the appreciation of his work. During the period that Lairesse developed his style in Liège and Amsterdam (between 1660 and 1670) there was little interest in French painting outside France. A valued “school” of French painting was a latecomer to the European scene, as was French art literature. Roger de Piles, in 1699, was the first to coin the notion of a French school, one that was on par with that of Italy and the Low Countries.13 “Schools” of painting with a large and exemplary production had been recognized in Italy and the Low Countries, and it was also in these two parts of Europe that a significant body of writings on art and, even more importantly, the establishment of a highly valued canon of artists had come into being. This happened first in Italy, but it soon took place in the Netherlands. There, canonization also manifested itself in a visual form: apart from the biographies by Karel van Mander (and even earlier short biographies by Hadrianus Junius included in a book published in 1588 on the province of Holland, which prompted authors of subsequent city descriptions to include artists’ biographies), several series of portrait prints of renowned artists had been published as of 1572.14 Nothing of the sort had occurred in France. In the Netherlands, moreover, an important corpus of art literature in Latin was created by such authors as Domenicus Lampsonius (1565), Franciscus Junius (1638), and Gerardus Vossius (1650). Their texts became internationally influential, as Thijs Weststeijn has recently pointed out, and proved fundamental for the development of French art theory, which began to take shape from the late 1660s onward.15 For Netherlandish authors of art literature in the later seventeenth century, from Samuel van Hoogstraten and Willem Goeree up through Gerard de Lairesse, and including the German Joachim von Sandrart, the Netherlandish tradition of writing on art was the central concern. Compared to Netherlandish and Italian art literature, the very recent French literature still remained peripheral.

In contrast to the many French collectors buying paintings produced in the Netherlands, collectors in the Netherlands did not acquire French paintings until the early eighteenth century.16 Tellingly, Dutch travelers, who jotted down numerous names of painters when in Italy, did not seem to have deemed any French painter worthy of mention when visiting France.17 The prestige of French painting still lagged behind its European counterparts. When the Académie Royale de Peinture in Paris was established in 1648, it had mainly socioeconomic goals; French painters still had to fight the very low estimation of artists, who were strongly bound to a highly restrictive guild organization that functioned according to late medieval traditions.18 Toward the middle of the century a number of young French artists had traveled to Rome and experienced an artistic freedom unknown in Paris. Lacking the support of a widely acknowledged history of their art with a prestigious canon of exemplary artists, nor possessing a theoretical corpus that could justify a higher status, they felt urgently the need to overcome this low status and promote painting as a liberal art. This was the context within which French art theory developed as of the later 1660s. Franciscus Junius’s book on art of the ancients and Vossius’s concise De Graphice were a great help in this regard. It was only at that time that classicism, based on imported sources, became a central ideology of the French academy. Only then did Poussin, who had made his career in Rome between 1623 and 1665 (with an unsuccessful interlude in Paris of less than two years) become, posthumously, a paradigm. Poussin achieved fame not only as a painter but also as a peintre philosophe. Who could possibly be more attractive as a symbol of the French academic painter par excellence “for an academy in search of its own programme and theory, in opposition to a non-theoretical and merely manual maîtrise”?19

We can safely say that French painters were unknown in Holland, apart from artists who spent their whole career (Claude Lorrain), or almost their whole career (Nicolas Poussin), in Rome—artists who were entirely associated with that city.20 In his 1678 treatise Van Hoogstraten does not mention a single French painter when he lists the special qualities of exemplary artists; he highlights only Italian and Netherlandish painters.21 In the rest of his text, he shows no interest in French art. He mentions sixty-five Italian artists, among whom are some fairly contemporary figures, six German, and seventy-six Netherlandish artists. Only three French names appear: Claude Lorrain, who went as a youth to Italy and probably learned his art there and made his career in Rome; the unlikely painter Martin Fréminet, about whom Van Hoogstraten has heard an anecdote. The name of Charles Le Brun pops up in an anecdotal interlude as well.22 Van Hoogstraten also mentions Le Brun as a teacher at the academy because he strongly approves of the organization of artistic training there under princely supervision; “I believe that through this way of teaching miracles will be brought forth,” he stated, obviously considering this a vision of the future.23 Even Poussin did not rank high enough to find a place in Van Hoogstraten’s work. This is rather unexpected because a few connoisseurs must have recognized his status by that time.24

To be sure, this is different with regard to Lairesse’s Groot Schilderboek. In the Teekenkonst, the only non-Italian artist mentioned is Poussin.25 In the Groot Schilderboek, however, the number of French painters referenced is much larger, and apart from Poussin, other Frenchmen also appear. Nonetheless, the dearth of references to French artists shows that Lairesse was someone for whom French art, even in the last part of his life and career, provided little inspiration.26 He does mention Poussin as an example of all kinds of qualities, often in the company of Italian artists—grouping him together with Raphael (nine times), Annibale Carracci (three), Domenichino (three), Barocci (once), Correggio (once), and Titian (once).27 He mentions Poussin several times alone as well, for Lairesse obviously attached great importance to his example, which he only knew through prints after his paintings. At the same time, it is clear from Lairesse’s references that he connected Poussin’s name and fame entirely with the art of Italy. He did not present Poussin as a French painter, nor did he associate him with France. Lairesse’s knowledge of, and admiration for, Poussin must have originated with Bertholet Flémal and Michel Natalis, both of whom would have moved for several years in Poussin’s circle in Rome. As Olivier Bonfait stated, for literati and artists in Rome, Poussin was, and would remain, a painter of the Eternal City in the lineage of antiquity, Raphael, and Annibale Carracci.28

Lairesse knew a few of Charles Le Brun’s works through prints (though not before the 1670s), but even he is not identified with exemplary qualities of French art. Lairesse listed his name three times in an enumeration of Italian artists (plus Poussin) as examples of such admirable qualities as succinctness, robustness, and beauty.29 The only time Lairesse cited Le Brun’s work on its own is when he pointed out some misslag (mistake) that he saw in a print after his work.30 Simon Vouet is mentioned as a renowned painter of ceilings, together with Correggio and Pietro da Cortona, and Lairesse records that he saw prints after his work in his youth.31 He names Pierre Mignard once because his middle tints were said to be too dark.32 These are the only references to French artists in Lairesse’s treatise. Missing entirely are important artists like Sebastien Bourdon, Eustache Le Sueur, Laurent de La Hyre, Jacques Stella, or Philippe de Champaigne.

In short, Lairesse was scarcely acquainted with French painting. He only knew prints after Poussin and Vouet, and, later in his career, after Le Brun. He admired the first and the last as artists who worked in the tradition of the antique and the greatest Italian masters. By the time he dictated the text for his Teekenkonst and Groot Schilderboek, he was familiar with some French art theoretical texts, notably those of Charles-Alphonse du Fresnoy and Abraham Bosse. In the 1670s, he came to know the strict views of the classicist theater, which were coming mainly from France, by attending meetings of the literary society Nil Volentibus Arduum.33 But it is notoriously difficult to pinpoint specific French theoretical sources in his writings.34 Lyckle de Vries rightly suggested that such authors were kindred spirits rather than “sources,” concluding that Lairesse’s “most important source of ideas and information was his own experience.”35 Lairesse’s style was shaped in the 1660s and did not change significantly after 1670; therefore, neither theoretical ideas issuing from France nor the example of painters working in that country could have played a significant role in his formation as an artist.36 Even the work of Poussin would mainly have been known to him through conversations with Flémal and Natalis (and perhaps through drawings they made after his work). In Lairesse’s early period, few reproductive prints after the master were available.

Italy and the Antique

It is undeniable, however, that when Lairesse arrived in Amsterdam in 1665, his style was decidedly different from that of his Amsterdam colleagues. Profane histories and allegories, including mythological scenes with nudes, would not have been a novelty for the Amsterdam elite, but the manner in which Lairesse painted them deviated considerably from that to which his audience was accustomed. This difference in style must have been, at least partly, an important reason for his instantaneous success and immediately created new preferences among this audience. But how would connoisseurs have situated his style, and how would Lairesse himself have presented it? What would this audience, his art dealers, and Lairesse himself have considered the main attraction, or, in modern terms, the principal “selling point” of his art? Houbraken wrote that it was through Bertholet Flémal that Lairesse “received insight into what one calls Antiek which causes the esteem for Italian painting.” He added that Flémal was a fervent student of archeology who made numerous drawings after antique monuments. He records that Lairesse had access to this studio material.37 Houbraken goes on to mention that early on Lairesse also studied the etchings of Pietro Testa, emphasizing that this was before connoisseurs in the Netherlands became acquainted with the Italian’s prints.38 The words “antique” and “Italian” are crucial here. Also important are the names of Testa, and in particular, Flémal because of the latter’s intense interest in everything connected with Rome and antiquity. Pietro Testa, a friend of Nicolas Poussin, was renowned for his passion for the antiquities of Rome; he made many drawings for the Museo Cartaceo, the project of Poussin’s patron and friend, Cassiano dal Pozzo.39 Flémal must have become well acquainted with this circle during his Roman period.

The image that Houbraken sketched of the foundation of Lairesse’s art stems from Lairesse’s own circle, and probably from the artist himself. It is the image of an artist nurtured within an ambiance in which the study of antiquity and the art of Italy, in particular Rome, were paramount. Abry mentioned in the life of Gerard’s father Renier de Lairesse that the latter was a good copyist and “because several paintings by Guido Reni, Veronese and other Italian masters were made available to him and which he imitated, he devoted himself to that learned and soft-flowing style.” (This reveals that such works were available in Liège).40 In his extensive biography of Lairesse, Abry refers to the artist’s use of Bertholet’s manner when discussing his early work and emphasized that, though he did not visit Italy, he penetrated “la beauté de l’antique” with such skill that it seemed as if he had studied in Italy itself.41

Sandrart’s biography of 1683, the only one that appeared while Lairesse was still active as a painter, begins by situating him in the artistic tradition of Liège, which brought forth such artists as Lambert Lombard, Frans Floris, Theodoor and Israël de Bry, Michel Natalis, and Bertholet Flémal. Sandrart recounts that Gerard’s father Renier first guided him in studying drawing and painting (as well as poetry and music), but that he learned as much from studying altarpieces in the city’s churches and convents.42 Sandrart then emphasizes that, at an early age, Lairesse decided to imitate Bertholet, whom Sandrart had described elsewhere as “generally called the Netherlandish Raphael.”43 After discussing some works by and patrons of Lairesse, Sandrart concludes that Lairesse’s works show “his practice and a complete knowledge of the theory, especially with regard to the knowledge of antiquity, architecture, the elegance of landscapes, of balance when creating space, and of how to develop ornament.”

Lairesse’s eagerness to peruse everything Italian and antique is also attested by Johan van Gool’s biography of Lairesse’s pupil, the wealthy Bonaventuur van Overbeek. Van Gool recounts that after the latter’s return from Italy, Lairesse gave him lodging in his house so as to be able to study thoroughly Van Overbeek’s numerous drawings recording the remains of Rome. He also studied the great number of drawings after antique statues and Italian art, as well as clay models and plaster casts, that Van Overbeek had bought from other artists. Lairesse used these beautiful drawings and models copiously for his own work, according to Van Gool.44 Thus, thorough expertise in antiquity and Italian art are key to Lairesse’s image as an artist, as well as his rooting in the Liège school of painting.

A Liège Tradition: Lombard, Lampsonius, Flémal, Natalis

These roots in the Liège tradition, however, have more consequences than are immediately apparent. It leads us to a powerful and truly classicist current in art and art literature extending from Lambert Lombard and Domenicus Lampsonius up to Lairesse’s activities in Amsterdam.45 Lairesse’s radical focus on what he called the “true Antique” (recht Antiek) was new in Amsterdam: “With the word true Antique I mean following the antique unadulteratedly.”46 The problem with other painters, Lairesse stated, was “that they do not study thoroughly the true Antique, nor the beauty of life.” Arno Dolders observed that Lairesse’s use of the term Antiek was unprecedented in both Dutch and French art theory.47 Lairesse used it as a characteristic of style referring to a certain kind of painting by artists from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; Raphael and Poussin are “antique painters,”48 and the “antique art of painting” can depict all manner of things, such as historical events, both secular and biblical, and allegories.49 These should always be set in ancient times, and the presentation should correspond rigorously to that period. Though life has to be the point of departure, it needs to be improved upon through a thorough knowledge of the ideal of beauty exemplified by antique sculpture, “like translating a book in another language . . . in a flowing style without slavishly tying oneself to the words.”50

This meaning of Antiek, however, appears not to be entirely unique. The same concept of “true antique” can be found in one other place: Karel van Mander’s biography of “Lambert Lombard, Painter and Architect from Liège.” Van Mander stated that Lambert Lombard had “become a father of our art of drawing and painting, begetting it there [in Liège] by chasing away the crude barbaric manner, to replace it with the true beautiful antique one [de rechte schoon Antijcksche], for which he deserves much gratitude and fame.”51 Van Mander described how Lambert had become a great connoisseur of antique sculpture52 and noted that he was a man of good judgment, being also a poet and a philosopher. He underlined that Lambert was an outstanding teacher, who, as a present day Chiron, raised heroes, like Frans Floris, Willem Key, and Hubert Goltzius. He was also great in “positioning figures, composing histories, and representing the affects and other circumstances” and “should be counted among the best Netherlandish painters of past and contemporary times.”53

Van Mander also tells his readers that he regretted that he was unable to lay his hands on a Latin booklet written by Domenicus Lampsonius, “secretary of the Prince-Bishop of Liège, also an exceptional lover of our art,” in which the latter described Lombard’s life. That Van Mander could write this biography without consulting Lampsonius’s text suggests that the image that he had set down of Lombard as the father of Netherlandish art, who brought “the true beautiful antique manner” to the Netherlands—an image propagated by Lampsonius—must have been generally held by artists of Van Mander’s generation. It also means that the existence of Lampsonius’s text of 1565 was still well known fifty years later. Lampsonius’s text presented Lombard as the exemplary universal artist and the apogee of Netherlandish art, comparable to the position Michelangelo held in Vasari’s account of Italian art. (Vasari, as a matter of fact, mentioned Lombard as the most important artist among the latter’s northern compatriots in his 1568 Lives.)54

The renowned humanist Domenicus Lampsonius, friend of Abraham Ortelius and Justus Lipsius, correspondent of Vasari, and best known to art historians because of his Latin epigrams accompanying the twenty-three engraved portraits of Netherlandish artists published in 1572, had been trained as a painter by Lambert Lombard. He, in turn, was the master of Otto van Veen. Van Veen certainly had a thorough knowledge of Lampsonius’s little book, which was part biography and part concise art theoretical treatise.55 Van Veen would have made his pupil Rubens familiar with it. According to Justus Müller Hofstede, Lambert Lombard must have been a role model, prefiguring Rubens’s “künstlerischen, diplomatischen, antiquarischen und humanistischen Leistungen.”56

The study of antiquity is central to the text of Lampsonius. Lambert Lombard, he writes, had discovered that all the excellent qualities of the art of the most admired Italian masters had grown from the breeding ground of antique models. For Lombard, antique sculpture had become the absolute artistic guideline for contemporary art; it was the essential form of art and simultaneously the supplier of indisputable rules.57 Lampsonius recounts that through imitation of exemplary antique sculpture, Lombard acquired knowledge of the essence of antique art, from which he distilled a science that he called his grammatica: fixed rules to guide the imitation of nature.58 If one does not follow this grammar, the imitation of nature forfeits its firmness and rules. A balance between natura and ars should be achieved, but Lampsonius emphasized the system of rules of ars.59 Remarkably, the essential elements of Jan Emmens’s description of a true classicist art theory, in his view dating from the late seventeenth century and based on French theoretical writings, are present here.60

Lampsonius stated that Lombard founded an academy in Liège, which advocated painting as an ars liberalis; he used both the words academia and schola, thus underlining its intellectual character. Its pupils would determine the art of the next generation in the (Southern) Netherlands.61 This academy must have followed the model of Baccio Bandinelli’s in Rome, where one drew, copied, and discussed the rules and practice of art.62 As Jochen Becker has pointed out, this milieu of the bishopric court in Liège could foster this new way of practicing art because it was closely tied to Italy and free of guild restrictions.63 This strong classicist tradition, with its focus on Italy and the antique, an “academic” adherence to the “rules of art,” and a “grammar” derived from antique examples, would still have been felt in the middle of the seventeenth century. Also in that period the dominant art in Liège had a distinctly classicist severity that would remain untouched by the contemporary styles in Antwerp and Brussels.

In an essay on the Liège painters following in Lombard’s footsteps, Pierre-Yves Kairis argued that almost a century later Bertholet Flémal still must have viewed himself as belonging to this venerable Liège tradition of Lombard. Kairis not only indicates several borrowings and references in Flémal’s works, but he cites the latter’s taste for archeological details and his conspicuous display of learned knowledge in this field, in costume, architecture, vases, basins, and other objects, which strongly recalls Lombard. This taste was inherited by Lairesse.64 Flémal must have studied Lombard’s work thoroughly and may even have had access to the repertory of drawings from Lombard’s studio (to which Lairesse may have had access, as well) that circulated in Liège before being sold in the eighteenth century. Thus, when Flémal arrived in Rome in 1638 “to observe and draw closely the friezes on imperial columns and triumphal arches in reality which he had earlier only seen in books and prints,” as Houbraken recorded, his background had prepared him for the intense and rigorous study of antiquity in Poussin’s circle. The obsession with antique sculpture and archeological correctness among Poussin and his friends fell on fertile ground with such Liège artists—not only Bertholet Flémal but also the Liège engraver Michel Natalis, who would teach Lairesse the rudiments of printmaking decades later.65

Michel Natalis, an engraver of many antique statues (including quite a few for the Galleria Giustiniana), also belonged to Poussin’s circle. It therefore seems probable that he introduced his townsman Flémal to this group.66 Pietro Testa, whose etchings would play an important role for Lairesse,67 was close to Poussin as well. Both Flémal and Natalis would have directed the young Lairesse’s attention toward the Italian’s prints. At the same time that Flémal was in Rome, the late 1630s and early 1640s, such young French artists as François Perrier, Charles Errard, Nicolas Loir, and Charles-Alphonse Du Fresnoy were also there, while Charles Le Brun arrived in 1642. These were all ambitious artists with intellectual pretensions: Du Fresnoy was working on his art-theoretical didactic poem De Arte Graphica at the time, while Perrier was making his repertory of classical sculpture (which Lairesse would warmly recommend). They, in turn, would play an important role in constructing the classical doctrine that Bellori and Félibien established fully in the 1670s and 1680s.68 It is likely that Flémal knew them all, though no documents remain to substantiate this. After his sojourn in Rome, Flémal worked for a short time in Paris, where he joined a group of young artists, most of whom he would have met in Rome, creating together in the Cabinet d’Amour at the Hôtel Lambert a sampling of the severe, somewhat chilly elegance of the new “attic” style.69 Thus, Flémal was thoroughly schooled in Rome at the same time as a group of young French artists who brought their innovations to Paris, stimulating the beginning of a new era of French art. Flémal returned to Liège with similar innovations. He must have brought many drawings of Roman monuments, prints by Testa, and probably drawings by and the few prints after Poussin that were then in existence. And he would have given Lairesse access to these resources, as Houbraken stated. More than any other artist, Lairesse seems as preoccupied by strict archeological correctness in architecture, objects, and costume as Flémal, intensively making use of the examples in the Galleria Giustiniana and Perrier’s Segmenta.

By the 1650s Flémal had become the court painter of the prince-bishop (as was Lombard a century earlier) and the reigning artist in Liège. The dependency on Flémal’s style and ideas of both father Renier de Lairesse and son Gerard was noted by contemporary biographers and can be verified by their works. In the case of Renier, knowledge of his art can only be deduced from a later print after a painting of the Death of Seneca; this composition unmistakably shows the style of Flémal.70 To Lairesse’s early work and its relation to Flémal (and Lombard) I will return below. Here it suffices to say that his own style was largely shaped before he landed in Amsterdam at the age of twenty-five.

Liège and Amsterdam: From Lombard and Lampsonius to Vossius

The ground was well prepared for Lairesse’s approach to painting when he arrived in Amsterdam. Thijs Weststeijn has pointed out that the importance of art theory written in Latin, a northern specialty, has been long overlooked in discussions about writings on art in the Netherlands.71 Apart from Franciscus Junius’s monumental book, Weststeijn drew attention to Gerardus Vossius’s short treatise De graphice, sive de arte pingendi published in 1650, which for those versed in Latin—as many connoisseurs and collectors were—would have been easy to read because of its conciseness and clarity.72 Vossius’s goal was to fit “painting in a systematic whole of humanistic learning,” comparing painting to rhetoric, “both in its basic aims and in details of the process involved in making it.”73 The educated art lover in Amsterdam could use this theory as a guideline for civil conversation. Thus the “concepts and commonplaces from Vossius’s treatise may have resounded in collections and workshops.”74

Vossius clearly knew Lampsonius’s treatise well. A part of Vossius’s text regarding the revival of painting in Italy and its greatest artists was grounded entirely in Lampsonius’s booklet; this passage cites Lombard’s opinion about these masters.75 “Lambertus Lombardus Leodicensis” is the only northern artist Vossius mentioned, and he presents him as “a famous artist of exceedingly excellent judgement,” who was able to assess the special qualities of the most famous Italian artists. Vossius concluded his treatise with Lombard’s judgment on the Italians and antiquity, and thereby emphasized the latter’s important position in the art of the Netherlands. In doing so Vossius approvingly refers to Lombard’s opinion that the ancients had not yet been surpassed: “as few Modern artists have acquired fame for their erudition . . . these rules [for imitating nature] have not yet been brought to the sureness and perfection they had acquired in Antiquity.”76 Weststeijn adds that Vossius’s text implicitly appealed to his readers, allowing them to fill in how the history of art continued. They could apply his ideas to the art they saw around them when visiting a painter’s studio.77

Might some knowledgeable Amsterdam connoisseurs have seen the young Gerard de Lairesse, this great Liège talent who had quite unexpectedly parachuted into Amsterdam, as a contemporary heir to Lombard, whose venerable position in the art of the Netherlands was known to them through the words of Van Mander and Vossius?78 Houbraken describes Lairesse’s arrival in Amsterdam as a kind of miraculous appearance to which the art dealer Hendrick Uylenburgh and the painters Jan van Pee and Anthonie de Grebber were witness. He recounts that they were initially aghast at the sight of this revolting figure (misselyk figuur; Lairesse’s face was disfigured because of congenital syphilis) but were privileged to observe how the man made an amazing painting, now and then interrupting his work to play music on the violin.79 Houbraken then emphasizes that within a few weeks Lairesse was a great success among Amsterdam art lovers. None of the biographers informs us why Lairesse chose the Netherlands, rather than France or Germany, when fleeing Liège. Although religious inclinations might have encouraged this choice (see the article by Schillemans), it certainly turned out to be an excellent career move.

Lairesse’s Early Work in Liège and Artistic Integration in Amsterdam

We have clarified that French art and theory could not have exerted any impact upon Lairesse’s artistic formation before 1670 and that Lairesse’s Liège background was formative for his artistic production. We may now consider the characteristics of Lairesse’s style in Liège and the changes it underwent during his first years in Amsterdam. This will allow us to situate Lairesse’s early development and to better understand the choices Lairesse made. I will not discuss the origins of the art theory that Lairesse would later develop. I will only state that, in my view, after his arrival in Amsterdam the solid foundation for his notions as a painter acquired in Liège would have been complemented by knowledge of Vossius’s treatise and Junius’s book, either through his own reading of them or from contact with educated Amsterdam art lovers. This was enhanced by the French theory of drama with which Lairesse had become acquainted in the 1670s through discussions with the members of Nil Volentibus Arduum. Especially important was Andries Pels, who published his little treatise in verse Gebruik en Misbruik des Toneels in 1681.80 All together these constituted a thorough framework for the very practical art theory Lairesse would develop.81 By 1670, however, his style had become fully formed and would not change significantly.

Both Sandrart and Abry emphasized the important commissions and the great number of paintings Lairesse had produced in Liège, thus making clear that he was already an admired painter before he fled his homeland. A good example of one of the earliest works we know is his Mercury Seeing Herse. This was probably the same painting that was seen by Philip Tideman and mentioned by Abry as among Lairesse’s early works (fig. 1; the painting would have been taller and wider originally). As has already been mentioned, Tideman remarked about this work “of his early period” that it was in a style “of which some do not speak with much praise.” He found it admirable, however, and judged it “to have much in common with the work of Poussin.”82 Lairesse followed Flémal in focusing on medium-sized cabinet paintings with profane subjects, a type of painting that Flémal—undoubtedly stimulated by Poussin’s example—had introduced in Liège; up to that point the production had been dominated by religious paintings for churches and cloisters. The manner of depicting drapery with many sharp, narrow folds, the emphatically antique costumes consisting of thin, slightly shimmering textiles that flutter unnaturally here and there, the friezelike arrangement of the rather squat figures, and the conspicuous piece of classical architecture as backdrop are all kindred to Flémal’s style (figs. 2 and 10). Lairesse depicted sharply outlined areas of rather harshly contrasting color in the foreground. A bright red emphasizes the two protagonists combined with a strong yellow, orange, bright white, and blue (now faded). These colors are set against an architectural background that is bathed in a strong light and is not toned down in color and definition. Tideman notes especially that the temple in the background “was quite boldly painted, entirely lit and white; if I had painted it that way, I am sure that the light would have spoilt the figures.”83 Even though from the beginning, Lairesse’s coloring is more agreeable and his contours less hard than Flémal’s, it is nonetheless clear what Tideman meant when he said that these early works were not appreciated by everyone and that they were “in the manner of Poussin.” Dutchmen were, after all, accustomed to subtle transitions in (often “broken”) color, shade, and tone that lead the eyes gradually from foreground to background. Tideman must have known from his master Lairesse, who may have heard it from Flémal, that for Poussin color primarily had an expressive function and was not meant to be pleasing or to create harmony and depth.

As would often be the case, however, Lairesse’s sources for the subject and its composition had nothing to do with Poussin, nor with Flémal, but consisted entirely of northern prints. He depicted a very traditional moment in Ovid’s tale of Mercury and Herse, as it appeared in prints of every illustrated Netherlandish edition of The Metamorphoses, all of which show a similar pictorial scheme. A group of young women carry flowers in the foreground, a few smaller figures are situated on a lower level in the middle ground, and a round temple, toward which the girls are moving, is placed in the background, while Mercury flies above them.84 It was, however, in the first place an etching by Wenzel Hollar after Adam Elsheimer (fig. 3) and a print from Goltzius’s Metamorphoses series (fig. 4)—in both, the book illustration tradition resounds forcefully—which supplied the motifs that Lairesse would use.85 More conspicuously than in these two examples, however, Lairesse emphasized a friezelike arrangement, for which he seems to have engaged with such prints as those after Roman friezes of The Muses in the Galleria Giustiniana.86 But he ensured that he infused this kind of arrangement with a lively spatial movement—often subtly adapting appropriate motifs from prints after Elsheimer and Goltzius—something that Flémal would not have been able, or willing, to do.87

Freely yet consciously borrowing motifs from prints and concealing these sources by thoroughly assimilating them accorded with what Lairesse would later write about this practice.88 As we will see, his expert use of prints when inventing compositions—very often northern prints of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries—is striking, but he did so within the stylistic framework of the Liège/Roman tradition. The similarity to Poussin that Tideman observed in Lairesse’s early work must have been due to the latter’s adherence to Flémal’s figure types, drapery and, as pointed out above, his use of color, light, and sharp-edged outlines.

A characteristic work from Lairesse’s Liège period, painted shortly before his flight north—I pass over the large-scale religious works from his Liège years—is one of his rare dated paintings, the Alexander and Roxanne of 1664 (fig. 5).89 The attraction of this subject for a painter like Lairesse was the invention by Raphael, engraved by Jacopo Caraglio (fig. 6). Moreover, he would have known that Raphael’s invention was based on a detailed ekphrasis by Lucianus of a painting by the late fourth-century Greek painter Aëtion. Lairesse obviously knew Caraglio’s print, which is reflected in the general disposition of Alexander approaching Roxanne, who sits with downcast eyes on her bed and her feet on a footstool, while a cupid removes her sandal and another putto lifts the veil from her head. All of these motifs, except for the footstool, are described by Lucianus.90 But here end the similarities to Caraglio.

Lairesse must have consciously tried to create his own invention. It seems that he knew about Sodoma’s famous fresco in the Villa Farnesina (fig. 7), either from a quickly sketched copy or from a description. This is confirmed by the inclusion of a motif of a cupid falling head over heels from Alexander’s shield, which is also found in the right corner of Sodoma’s painting. That deviates from Lucianus’s description of two amorini holding a shield on which a third one sits prominently “as if he is their king,” which appears in Raphael’s composition. Another jocular motif, described by Lucianus, are two amorini carrying a spear as if it is a heavy beam; this element is absent in Sodoma’s painting but features behind Alexander’s back in Raphael’s invention. Lairesse made it even funnier by painting three putti who push and pull a huge spear upright—a witty reference to the soldiers pushing and pulling in Rubens’s famous Raising of the Cross, known by every connoisseur through Witdoeck’s engraving —while a fourth putto hangs like a flag atop the spear.91

Also in this work, Lairesse actively engaged with prints by and after Hendrick Goltzius. In Goltzius’s Mercury Approaching Herse in Her Bedroom, from the Metamorphoses series (fig. 8), Lairesse recognized the latter’s brilliant adaptation of Raphael’s figure of Roxanne—seated with downward-looking eyes on a huge bed, leaning on one arm and touching her breast with her other hand.92 Lairesse’s Roxanne is, in turn, a clever adaptation of Goltzius’s Herse, as is the sizeable canopy bed on which she sits. The amorini holding open the huge curtains of the bed, and the platform on which it is placed, draw upon another engraving by Goltzius, his well-known Venus and Mars Making Love (1588) after Bartholomeus Spranger’s design (fig. 9). In a highly inventive way, Lairesse once again blends motifs from sixteenth-century Italian and Dutch Mannerist prints into a convincing invention. Though he translates everything into severe “antique” forms and proportions, he is able, through his familiarity with Goltzius’s prints, to infuse the composition with more liveliness and spatial movement than both his Italian examples and those by Flémal would have allowed.

The eye-catching row of high but rather slender columns with Corinthian capitals parallel to the picture plane and the placement of an enormous red curtain hanging before it are evocative of the background of Flémal’s Héliodorus Chased from the Temple, a painting Lairesse must have known well (fig. 10).93 The fanciful buildings seen in the background seem to echo Lambert Lombard’s architecture. As in Lairesse’s earlier painting, the draperies still recall Flémal’s rather flat and sharp definition. Very striking again are the bright red patches of the huge bedcurtains and the fluttering red mantle of the cupid at the right, all with their sharp-edged outlines. The type of young Roman boy also derives from Flémal.94 The soft limbs of both the boy and the male hero, who looks almost feminine with his slender proportions and smooth legs, are very different however. Might this be the outcome of what Lairesse would have learned from copying work by Guido Reni, as his father was said to have done? Also the female type of Roxanne and her smooth skin display a definitively Reni-like flavor.

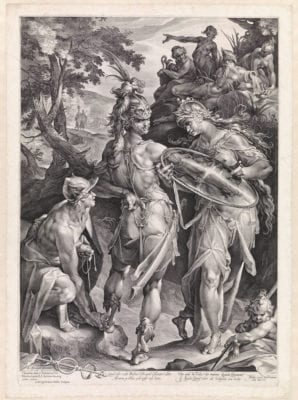

As we have seen, we find quite a few resonances of prints by and after Goltzius and other Mannerist engravers in Lairesse’s work from his early period; they are often intelligently incorporated into paintings of different subjects. Lairesse never quotes literally but always changes the poses and the placement of figures in relation to each other. Examples include the groups of two standing and two seated women in the foreground of Minerva Visiting the Muses (ca. 1667),95 which are adaptations from figures in Goltzius’s famous Judgment of Midas of 1590. Also the many references to Goltzius’s prints of the Life of the Virgin (1594) in Lairesse’s series of the Infancy of Jesus (ca. 1665–66; see the article by Schillemans in this volume); and the beautiful little painting of Diana and Her Nymphs after the Hunt (ca. 1668),96 for which he studied Jan Saenredam’s print after the Discovery of Callisto’s Pregnancy (1606) by Paulus Moreelse. Or, most strikingly, Minerva and Mercury Arming Perseus (ca. 1666; fig. 11), in which he clearly responded to the 1604 engraving of the same subject (fig. 12) by Jan Harmensz Muller after Bartholomeus Spranger.

Minerva and Mercury Arming Perseus is an excellent example of the change in Lairesse’s style shortly after settling in Amsterdam. Lairesse would have appreciated Spranger’s “correct” rendering of classical gods and their attributes, but he demonstrates how Spranger’s unnatural and stylized poses and proportions can be made “recht antiek” by painting broader shoulders and larger heads, depicting them from front or back or in profile and parallel to the picture plane, avoiding strong torsions, and omitting overly fanciful ornaments. The group is turned in reverse, and the narrative interaction is made more natural by turning Perseus’s gaze toward Mercury’s tying of his winged sandal. The figures are placed on a narrow platform against the emphatically “antique” architecture of high columns supporting a round temple. The Muses seated on both sides again recall the embracing Muses in the foreground of Goltzius’s 1590 engraving, but they were transformed by Lairesse into Poussinesque types. Compared to his earlier paintings, the figures have acquired a rounded solidity; particularly in the male figures this is achieved by heavier shadowing. But both male and female figures are modeled with a softness that is far removed from Poussin and even more so from Flémal. It is attained by way of rendering skin through carefully painted transitions from light to half-shadow, less accentuation of the musculature, and much softer contours. The folds of the fabric have become more supple, and the colors have changed. No glaring accent in bright red remains, nor do cool blue, white, and silver gray against dull or brownish-gray appear in the background. We now see a broad range of strong but often “broken” colors from cool to warm: warm red, purplish brown, orange-brown, dark yellow, pink and very light-colored flesh tones, harmoniously distributed over the surface to create a pleasant overall effect. This coloring, which includes the deliberate use of houding—careful transitions in color and tone to suggest space and create harmony—recalls the late mythologies of his much older Amsterdam colleague Ferdinand Bol (fig. 13).

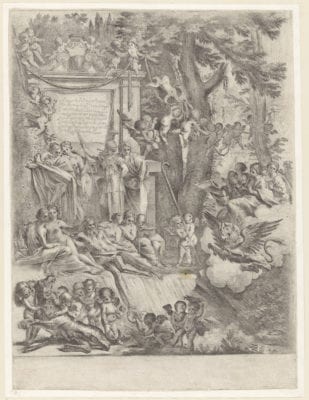

Lairesse’s study of Pietro Testa’s prints is visible in several works that were painted in his early Amsterdam years. The impact is quite obvious in his Thetis Dipping Achilles in the Water of the Styx (ca. 1665), probably painted around the time he settled in Amsterdam, and in his Venus Giving Armor to Aeneas, dated 1668 (fig. 14). Both of these are based on prints by Testa of the same subjects.97 A more subtle relation to Testa may be found in The Deification of Aeneas (ca. 1667),98 and the Allegory of Abundance, dated 1667 (fig. 15; often called the Allegory of the Peace of Breda),99 for which etchings by Testa of different subjects supplied compositional ideas and motifs.

Lairesse’s Allegory of Abundance, the earliest dated work of his Dutch period, already shows the full development of his characteristic style in a work with small-scale figures. The general composition is grafted (in reverse) on an allegorical etching by Pietro Testa (fig. 16).100 In both works we see young women and a bunch of playful children piled up around a marble monument. A group of women sits at the left side under a tree, and Lairesse transformed the river god lying below the monument into a young woman. The cascade in Testa’s print is removed, but the stream is still there; a couple of swans and a naiad swim in it. Lairesse avoids, however, further correspondence in the poses and gestures of the women and children. Central in this painting is a standing woman with a winged scepter topped by a hand and eye. She is Industria (industry or diligence), as Ripa’s Iconologia shows, a book warmly recommended by Lairesse and carefully consulted by him for this painting.101 She looks at the seated woman who, with her many breasts, represents fertile nature, and points to the statue that is crowned with flowers. As with his “living” figures, Lairesse does not imitate exactly a specific antique statue. Rather, the marble woman is an amalgam of several female statues represented in François Perrier’s Segmenta, the best-known book with prints of statues from classical antiquity made at the time that Flémal was in Rome. Lairesse would have known the book by heart, and he later recommended that painters study it, preferring it to Jan de Bisschop’s Icones.102 This painting must have been a commissioned chimneypiece—perhaps his first in Amsterdam—and he did his best to make a memorable work that would have dazzled Amsterdam connoisseurs. He included, however, elements that deviate from his earlier works of the Liège period but would have been familiar to his new audience.

The handsome women and children have a classical beauty and grace that had not been seen before in Amsterdam, while the airy lightness of the colors of the draperies and skin tones, fitting for the atmosphere of blossoming springtime, would have been considered an amazing novelty. The painting shows a solidly constructed composition, in which Testa’s rather strict arrangement of figures in rows parallel to the picture plane has been enlivened by imbuing the central part of the painting with a slightly curved spatial movement. This extends from the statue in the middle distance down toward the foreground by way of a supple linking of the figures through gesture, light, and color. We do not encounter such an ordonnance—coming forward toward the viewer, with figures addressing the viewer directly—in his earlier works, and it is entirely foreign to Flémal. Lairesse adopted compositional practices that we know well from artists such as Govert Flinck and Ferdinand Bol.103 The attractive woman closest to us even seems to refer to a Venus by Ferdinand Bol (see fig. 13); he transformed the goddess into a nymph of antiquity with broader shoulders, smaller breasts, and a wider, straight-nosed face.

In the foreground stands a golden vase with a floral still life that seems like an intentional reference to the most renowned and most expensive still-life painter of that time, Jan Davidsz de Heem. Furthermore, the landscape shows Lairesse’s knowledge of the artistic trends in his new country: the rather undifferentiated trees and leaves from his Liège period are replaced by a much greater variation and detail that recall the idealized, parklike Italianate idylls of the successful Amsterdam landscape painter Frederik de Moucheron. Its attractive refinement is quite different from the few landscape backgrounds we know in works by Flémal, and it has nothing in common with Poussin’s landscapes.

If one compares the playful children with those of Poussin or Testa, it is clear that—as Lairesse later would impress upon his readers—drawing from life, carefully observing nature, and subsequently choosing the most beautiful examples so as to achieve as perfect a state of nature as possible must indeed have been his practice. The liveliness of his young children is unequaled. They are slightly more mature than the toddlers of his example, Pietro Testa, and resemble Duquesnoy’s type of beautiful “Greek” children (which he would have known through plaster casts).104 He translated them into painting but only after having made studies from life and shaping them into his own ideal.

That Lairesse had been looking carefully at the work of Ferdinand Bol, the favored artist of the elite at that moment, is most evident in his large painting of the following year, Venus Giving Armor to Aeneas, dated 1668 (see fig. 14). Lairesse must have seen the work of the same subject (or likely a smaller version of it, either a copy or sketch) that Bol painted as a huge wallcovering for the house of a wealthy widow in Utrecht (see fig. 13).105 Lairesse employed a similar basic scheme to locate the main elements: the pointing Venus, her still somewhat hesitant but grateful son, and the putti presenting the armor, here in mirror image. But he would have wanted to transform this composition into a classically sound work, not only by changing the figure types but also by making a painting in which the figures move parallel to the picture plane in a more relieflike composition, thereby ensuring that all the elements were recht Antiek. To study how his admired “Roman” models had treated the same subject, he had at his disposal the print by Testa of ca. 1640 (fig. 17),106 and a composition by Poussin (fig. 18), which he must have known through a print by Alexis Loir.107 Testa’s general disposition of the closely knit group of Aeneas, Venus, and the five amorini holding the shield and other pieces of armor returns in Lairesse’s work. He also included the cloud on which Venus reclines, which he knew from another etching by the same master, the Sacrifice of Iphigenia (all in reverse).108 He provided Venus with an elliptically fluttering cloak, a motif stimulated by Poussin’s stylized drapery and similar to the conventional rendering on Roman reliefs but “naturalized” here by Lairesse. The river god reclining next to the armor seems to combine elements of Testa and Poussin, but Lairesse positioned him close to the picture plane in the foreground. Following Testa’s example, he found it necessary to correct Poussin archeologically by painting some of the episodes mentioned in Virgil’s ekphrasis of the shield: the personification of Rome on her throne can be recognized in the middle, and the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus appears at the upper left. Poussin had not included these features, as it would have required minute detail, which he obviously avoided as a painter.109 Bol did not include them either.110

In this painting Lairesse has fully developed his characteristic, classically proportioned, handsome types for both young females—goddesses and nymphs—and for youthful, smooth-limbed male heroes. The putti are now even more developed and come closer to the strapping infants of Ferdinand Bol. It seems as if, with this painting, Lairesse wanted to comment critically upon Poussin’s composition. Lairesse’s flowing forms, tightly linked in an agreeable circular arrangement, his graceful and handsome protagonists lovingly bound together, the strong “presence” of the figures, slightly moving in our direction and coming very close to the viewer’s own space, all contrast significantly with Poussin’s severe and static juxtaposition of sharply defined, monumental forms. By now, his coloring and manner of painting had become very different from that of Flémal, and, as he might have realized, also from Poussin. After all, Poussin’s Venus Giving Armor to Aeneas is typical of the artist’s style around 1640, the time that Flémal spent in Rome. Lairesse’s harmoniously distributed colors, the careful differentiation in depicting all the materials—soft, hard, dull, shining, glittering—the sensual rendering of the nude flesh and the softened contours and subtle shadowing that creates space and organizes the ordonnance are almost an antithesis to Poussin’s manner, in which an illusionistic depiction of materials plays no role. Poussin emphatically avoided sensual effects in the rendering of surfaces, and the colors are meant neither to be pleasing nor to create depth and harmony but to strengthen the separate forms and make them more meaningful. Moreover, the viewer is denied the possibility of feeling involved in the scene.

In Lairesse’s Venus Giving Armor to Aeneas, some characteristics still recall his early style, such as the extremely bright red fluttering mantles of Aeneas and of one of the cupids, which are sharply outlined against the background. But the manner of painting he had developed in Liège has been merged with many stylistic elements that he had picked up in Amsterdam. This would have been appreciated by his Dutch audience. New are devices that seem to have been favored by Dutch artists in particular, such as koppeling (joining, so as to make a coherent composition) and houding (the interrelation between color, tone, light, and shade to create a convincing suggestion of three-dimensionality and harmony in the overall composition), which together create welstand (which includes for Lairesse harmony and beauty based on classical forms, grace, and decorum). We learn from his later writings that mastering these concepts had become paramount in his thinking about the creation of a painting.111 Such devices were alien to Flémal, whose compositions are discursive and whose merciless colors and sharply cut contours often seem deliberately to collide. Flémal did not concern himself much with creating harmony and achieving a coherent space through color and light or convincingly linking his figures.112

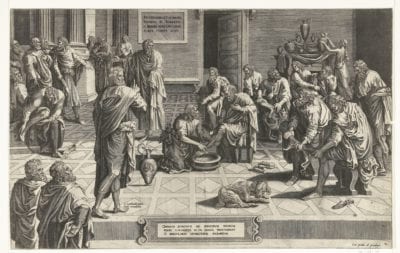

Probably in the same year, Lairesse produced an entirely different type of painting, the monumental Anointing of Solomon (fig. 19). He also made an etching of this composition (dated 1668), which was dedicated to Maximilian-Henry of Bavaria, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne and Prince Bishop of Liège (fig. 20).113 It seems likely that the painting was also a commission from Liège and that it contained a political message.114 The painting must have been cropped on all four sides; at the top a large strip of canvas is missing. In the print’s dedication, the inventor is emphatically mentioned as Gerardus de Lairesse Leodius Pictor, that is, painter from Liège. Timmers has already pointed out that in the etching (the painting was not known at the time), which he considered one of Lairesse’s best prints, the artist’s origins in the Liège tradition were more strikingly present than in any other print. He even remarked that the bearded soldiers at the left stemmed from the “romanist” style introduced by Lambert Lombard and that using the lower edge to cut off figures in the foreground was a favorite motif among Liège painters.

It is indeed remarkable that in several paintings Lairesse employs this motif of onlookers or commentators standing in the foreground at a much lower level than the main scene and visible only from the waist or shoulders upward, mostly from the back or en profil. In this composition, the motif can be seen in the figures at the left gesturing toward the main group and two soldiers in the middle leaning on a balustrade (removed later from the painting by cropping). Both groups, like the beholder of the painting, look up at the ceremony. An engraving of the Pedilavium after Lambert Lombard, published by Hieronymus Cock, is a good example of the latter’s use of this motif (fig. 21).115 Lombard’s pupil Domenicus Lampsonius, in one of the rare works that we know by his hand, the altarpiece representing Calvary,116 also depicts onlookers standing at a lower level in the foreground. Lairesse must have been familiar with Lampsonius’s painting, made for the cathedral of Hasselt, not far from Liège, as is made clear by the bystanders in another work by Lairesse, the rather early Ecce Homo.117 Lampsonius’s pupil Otto van Veen was quite fond of the motif, as well.118 Lairesse continued to employ it in other works, notably the large, early Baptism of Saint Augustine, the Circumcision from the series of the Infancy of Jesus of ca. 1665–67,119 and much later the Allegory of the Prosperity of Amsterdam and the oil sketch for the large Allegory of the Glory of Amsterdam. It is a highly “unclassical” motif, which he combined with the “Caravaggist” device of situating dark silhouetted forms close to the picture plane, so as to set off the strongly lit and brightly colored group of figures further recessed in space.

Within this closely knit group he created a remarkable suggestion of space between the figures through light, half-shade, and color. The painting demonstrates Lairesse’s interest in achieving harmonious effects in a theatrical setting. The theatricality of the whole scene, in fact, is underlined by the extremely elaborate architectural “side wings,” the central “stage set,” and “backdrop.” The grouping looks as if it is a tableau vivant with an audience in the foreground. By combining different methods with great freedom, Lairesse presented himself as a painter firmly rooted in a “romanist” tradition of recht Antiek, who was, at the same time, capable of a remarkable stylistic flexibility and an openness to new possibilities that could enhance the attractiveness of his art for an elite audience in Amsterdam, and, if necessary, in Liège. He would continue to receive prestigious commissions from his native city—among them large altarpieces, even the high altar of the Liège cathedral—though his patrons knew that he adhered to the reformed religion.

By the end of the 1660s, Lairesse had fully developed a very recognizable style. He had been educated in the “classicist-romanist” Liège tradition stretching from Lombard to Flémal. Indeed, his strong belief in a system of rules (ars) originated there. He would have presented himself in Amsterdam as an artist geared toward the example of antiquity and the art of Rome through Poussin, who was viewed within the Italian lineage of Raphael, Annibale Carraci, and Domenichino and not yet as a paragon of French art. By analyzing his early works, I hope to have made evident that when Lairesse devised his inventions, the study of prints by and after Netherlandish Mannerist artists also added considerably to the development of his style. This certainly contributed to the liveliness of his compositions, but he would have considered the use of these prints as a practical matter and something to be concealed.120 Having arrived in Amsterdam, he quickly and brilliantly absorbed elements from the successful styles current in his new environment. In the following years, his views on art would be strengthened through his contact with Nil Volentibus Arduum’s adherents, who propagated French classicist theater. Lairesse’s relation with Andries Pels, who published his treatise on theatre only in 1681, dates to 1668, when he designed the title print and two scenes for Pels’s play Didoos Doot.121

Many aspects of Lairesse’s style and his aims as an artist might have been kindred to those of classicist painters in France. This was due to the fact that their art was shaped by similar models, from antiquity to Poussin. Nevertheless, we may safely state that the style that proved such a resounding success in his new country was completely formed before any knowledge of French art theory or French painting (as developed around the Académie Royale in Paris) could have reached him. In fact, a connection with French art and art theory would not have been considered a valuable asset in Amsterdam in the 1660s. Rather, Lairesse’s fundamental adherence to and emphatic display of what he called the recht Antiek, in addition to his great talent as a painter, must have immediately made a decisive impression on Amsterdam art lovers.