This paper examines the production methods employed by Dirk Vellert in designing a series of glass roundels of the History of Abraham. A newly discovered painted glass roundel in Bristol provides evidence that Vellert preserved his completed Abraham patterns in his shop, and that he later traced and revised them to create new designs. The Abraham series supports earlier observations about Vellert’s techniques seen in his designs for a Life of the Virgin roundel cycle. Vellert’s method of retaining and revising stock patterns has parallels in the works of other artists working in other media as well.

Although many Flemish artists of the early sixteenth century left us with few or no surviving drawn sheets, a relatively large number survive by the leading Netherlandish stained-glass designer Dirk Vellert, who was active in Antwerp from about 1511 to 1547. Vellert’s oeuvre includes more than fifty drawings, the majority of them designs for small-scale painted-glass roundels, works that were commonly conceived in series. In Vellert’s designs for cycles of the Life of the Virgin of 1532 and the History of Abraham from about 1535, several sheets survive in various stages of completion, and the Life of the Virgin preserves some scenes that were drawn in more than one version. These drawings reveal significant aspects of Vellert’s working practices, as I first discussed in an article, “Drawings as Intermediary Stages: Some Working Methods of Dirk Vellert and Albrecht Dürer Re-examined,” published in Simiolus in 1991, and later elaborated in my dissertation, completed under Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann’s guidance in 1992.1 My analysis focused on Vellert’s Life of the Virgin, since this large cycle provided enough material to observe several of the compositions evolve in a series of revised stages. The History of Abraham, however, consists of only three drawings and one glass roundel, each representing a different, unrelated scene: the sheets The Lord Appearing to Abraham; Abraham and Pharaoh; and Abraham Rescues Lot, all in the British Museum (figs. 1–3), and the glass roundel The Lord Makes His Covenant with Abraham, painted by the artist himself and signed with his monogram, now in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 4). Vellert’s Abraham drawings are heavily revised–two of them are, in fact, more dramatically reworked than any of the sheets in the Life of the Virgin–but because comparable links do not exist between the compositions, I concluded in my dissertation that at the time there was insufficient evidence to analyze the stages of their production.

However, during the last two decades, Northern painted-glass roundel design has attracted increasing scholarly attention, and in recent years the Corpus Vitrearum international committee has expanded its efforts in documenting sixteenth-century Netherlandish stained glass.2 As a result, many previously unknown roundels of varying quality have been gradually coming to light, particularly as they are systematically listed and illustrated in the Corpus Vitrearum’s growing series of checklist volumes. Among these newly discovered works is a painted glass roundel depicting the Lord appearing to Abraham, which now fills a gap in Vellert’s History of Abraham cycle (fig. 5). This roundel, preserved in the Old Baptist College at Bristol University, in Bristol, England, is undistinguished in quality and is reproduced, without attribution, in the Corpus Vitrearum checklist volume for Flanders, published in 2011 by C. J. Berserik and J. M. A. Caen.3 It was repainted with brightly colored enamels and refired, most likely in the eighteenth century, and thus its present condition masks whether it was painted by Vellert himself, by a close follower, or by an unrelated hand.4 However, the roundel partly records the preliminary stage of Vellert’s traced and reworked drawing The Lord Appearing to Abraham in the British Museum (fig. 1). Thus, although modest in quality, the roundel provides some notable insight into Vellert’s method of working in stages, a practice comparable to the one he followed in the Life of the Virgin.

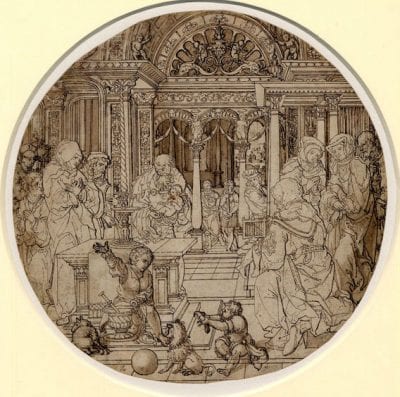

Vellert produced The Lord Appearing to Abraham drawing in several steps, using different inks and different drawing styles. He first laid out the composition with rigid traced outlines in pen and brown ink over black chalk–made, we can presume, from an earlier, now-lost drawing–depicting the Lord addressing Abraham, who is seated in a portico. This meeting is most likely the one described in Genesis 18:18–33, in which God revealed to Abraham his plan to destroy the sinful cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Sarah appears in a doorway in the right background, while God reprimands her for laughing at his message that she will bear a child despite her advanced age (Gen. 18:13–15). In the second stage of the composition, Vellert revised the spatial relationship between Abraham and the Lord, using thicker, more fluid pen strokes to redraw the Creator, who was at first standing statically on the portico step. To make the scene more dynamic, Vellert reduced the Creator’s size and elevated him into the sky, soaring on a cloud toward Abraham. In this second stage, Vellert adjusted the position of Abraham’s head, changing it from a three-quarter view to a profile, gazing upward toward the Creator. The artist also made numerous other alterations: the horizon of the landscape background was lowered and redrawn to replace many of the buildings with hills, and at the left, faint pentimenti under the building in which Sarah appears a second time, behind the scene of Abraham entertaining the three angels, reveal an initial tracing of a landscape with trees and a castle tower. In addition to the extensive changes in the foreground of the drawing, in the second stage Vellert deleted several background scenes by sketching over them with thicker, more rapid strokes of darker ink and with wash. For instance, he removed the scene of God reprimanding Sarah at the right by imposing a curtain and a column over it and by adding three figures to the background. He also added, with darker ink, the three angels walking in the landscape in the left background and the three angels in the sky at the right. Other adjustments were made: new columns were added, with heavy ruled lines, to the portico in which Abraham sits, arches were appended to this structure, and the decoration of its pediment was changed from narrow rectangular openings to wide swirls.

The roundel in Bristol partly follows the initial traced version of Vellert’s drawing (fig. 5). In the roundel, the Lord stands full-length on the portico step and Abraham’s head turns toward him in three-quarter view. A column divides the space in the foreground of the roundel as in the tracing, and a town with a castle appears in the background, corresponding to the one Vellert sketched over in the revised stage of his drawing. The glass painter must have had access to the earlier version of Vellert’s design, which presumably was considered a finished pattern appropriate to use for a roundel. This first stage could have been preserved, in a drawing or a painted roundel, as a workshop sample from which a patron could choose, with the option to revise the scene to create a new, more dynamic, or more personalized version. The fact that the earlier stage of the design appears in the Bristol roundel suggests that it enjoyed success as a roundel formula.

A similar method of production occurs in Vellert’s earlier Life of the Virgin roundel series. The design for the Presentation in the Temple exists in two sheets, one a sketchy and uncompleted version drawn with pen, brown ink, and wash on cream paper, and the other a highly finished chiaroscuro drawing, executed on greenish-blue prepared paper with pen, brown ink, and white heightening (both British Museum, fig. 6, fig. 7). As I argued in 1991, Vellert’s sketchy, unfinished drawing represents not a transitional study toward the finished sheet, as one might expect, but a later stage of the design.5 The sketchy drawing was, as were the Abraham drawings, executed in two steps. In the first, the composition was first traced with fine, rigid outlines, over which Vellert superimposed changes with darker, more fluid pen strokes and wash. The initial traced stage of this drawing follows the finished chiaroscuro sheet, and the sketchy lines are subsequent revisions. For instance, the head of the boy seated on the altar steps was drawn in profile in the traced version, just as it appears in the chiaroscuro drawing. Vellert then reworked the boy’s head into a three-quarter view in the second stage. Besides altering many details, Vellert rethought the entire composition in this second stage, enlarging its actual size and adding new figures and more empty space. Thus the drawing on cream paper includes rapidly drawn figures such as the seated boy holding a bird in the foreground and several subsidiary figures at the left and right, not found in the traced version or the chiaroscuro sheet. The jewel-like chiaroscuro drawing of the Presentation in the Temple may have been made to preserve one composition from Vellert’s first set of designs for the Life of the Virgin. It could have served as a sample pattern, kept in the workshop as a formula that a patron could choose and have revised, if desired.6 We can note that Vellert’s first stage of the Presentation in the Temple survives as a painted-glass roundel, which indicates that it was in use as a design.7

In his History of Abraham, Vellert reworked the drawing for Abraham and Pharaoh, also made over an initial, traced version, with revisions that are as equally extensive as in the Lord Appearing to Abraham (fig. 2), and in a third sheet, probably representing the Rescue of Lot, he altered details in a similar manner (fig. 3). Vellert’s Abraham designs may have been, as I have suggested for the Life of the Virgin series, first executed as a finished set of patterns, which were then preserved and subsequently traced and revised to create new scenes.

Since Vellert’s known Abraham designs each present multiple episodes from the biblical story, the entire cycle was likely densely illustrated. Moreover, many of the scenes are rare in Netherlandish art, which suggests that the series was intended to be large in number. Although its only components are known from the three surviving drawings and the one painted roundel, clues to other, now-lost scenes in Vellert’s cycle may possibly be found in another, anonymous group of Abraham roundel designs, executed in glass and paper in multiple versions of varying quality and dispersed in various museums and other collections. On the basis of style and subject, the Bristol roundel can be tentatively placed with these designs. While some scholars have ascribed the group to Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen (1472/77–ca. 1533), its authorship remains unclear.8 Vellert’s roundel The Lord Makes His Covenant with Abraham in Amsterdam is very close in composition to one of these designs, preserved in a less accomplished pane in the Victoria and Albert Museum, although the two roundels differ in many details (fig. 4, fig. 8).9 We can speculate that Vellert and other artists shared workshop patterns, or knew of intermediary sources, to explain such correspondences. However, some roundels in this anonymous group are so close to Vellert in figure type and composition that we may conjecture that the entire group reflects lost episodes in the artist’s Abraham series. A striking example is the anonymous Abraham witnessing the burning of Sodom, known in several panes from different hands, which recalls not only Vellert’s substantial figure types but also his signature landscape motifs of plantain plants and spiky trees (see, for instance, fig. 9 and fig. 10).10

Another aspect of Vellert’s working method can be observed in his drawing The Lord Appearing to Abraham, revealing that the artist not only reused entire compositions as he did in the Life of the Virgin, but that he also traced individual motifs to rework into new scenes, even ones with different subjects. The small traced figure of God in the right background of this drawing (fig. 1), which Vellert partly covered over when he made his revisions, is virtually identical in dress and pose to the figure of the Lord in the center of Vellert’s roundel The Lord Makes His Covenant with Abraham in Amsterdam (fig. 4). Both figures raise their right hand in blessing and hold a globe in their left hand. The large traced figure of the Lord in the foreground of the drawing varies from its counterpart in the roundel in that he holds his robe with the right hand, while raising the globe with his left. The version represented by the small traced Lord and the Amsterdam pane might reflect an intermediary stage known to the painter of the Victoria and Albert roundel (fig. 8), which also shows the Lord blessing with his right hand (although he lowers his other hand to hold his robe rather than a globe). The Bristol roundel, however, mixes various elements into a hybrid of the Creator type (fig. 5). The figure follows the earlier traced version in Vellert’s drawing in the position of the Creator’s hands, although omitting the globe, while he wears, not the intricately-wrought three-tiered papal tiara represented in Vellert’s versions, but a simpler crown, as seen in the roundel in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is possible that Vellert’s shop created a series of reworked designs, with varying motifs, to provide a range of models from which to choose, and that the painter of the Bristol roundel had access to one or more of these designs. Alternatively, that the painter of the Bristol pane created a pastiche of motifs and poses derived from Vellert, or that the Bristol pane and Vellert’s roundel relate to a common source, cannot be ruled out.

We can conclude from the comparisons between Vellert’s drawing The Lord Appearing to Abraham and the Bristol roundel that Vellert’s method of drawing in stages, and of recording stock models that could be repeated and revised, is not unique to his Life of the Virgin series. Nor was this working practice unique to Vellert. I suggested in 1991 that Dürer drew his Green Passion cycle in comparable stages and that his sketchy Entombment, executed with pen and ink on cream paper (National Gallery, Washington, D.C., inv no. 1972.13.1) was a traced, revised version of an earlier design preserved in a finished chiaroscuro drawing on prepared paper (Albertina, Vienna, inv. no. 3095).11 In recent years, numerous studies have explored how artists working in a range of media, including panel painting and sculpture, similarly preserved stock compositions in their workshops for later reuse and revision.12 The glass roundel in Bristol, although an unattributed work of small scale and unremarkable quality, nevertheless adds to our understanding of artistic production in the sixteenth century. An analysis of this roundel, moreover, demonstrates that the study of Netherlandish stained glass, a medium that has long been marginalized and neglected in the writing of Renaissance art history, can offer insights into the techniques and production practices employed in more traditionally familiar works of Northern art.