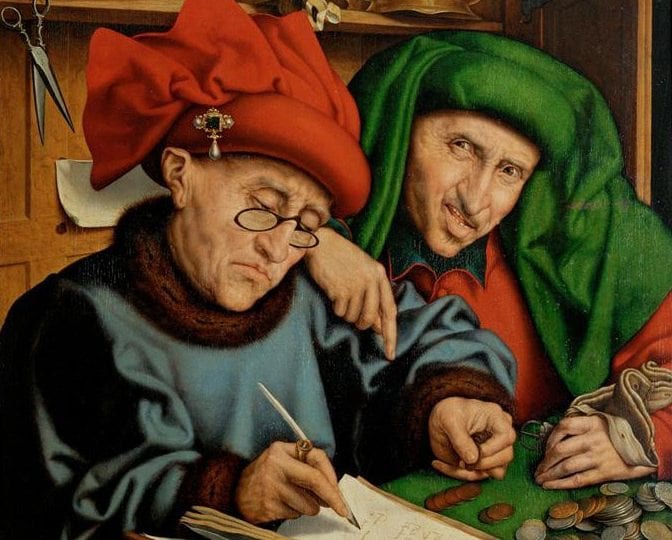

One of the formative images of later Flemish genre paintings, Quinten Massys’s Tax Collectors has been rediscovered (now Liechtenstein Collection, Vaduz). Its ledger clearly reveals the proper designation of the figures, despite interpretations of their activity as banking; one of them, wearing glasses, appears to be inspecting accounts. Telling markers of Massys’s own authorship (ca. 1525–30) reveal that his large workshop based at least some of the better copies on this painting. The subject clearly relates to local ambivalence in Antwerp about taxes and the money economy, especially during a period of financial recession. The article concludes with a discussion about later variants derived from Massys’s prototype, especially those by Marinus van Reymerswaele (Paris, London, plus lesser variants), but the theme is still present in Rembrandt’s 1628 Moneychanger (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) and addressed anew in his etching of Jan Wtenbogaert (1639).

Art history sometimes enables scholars to know an influential missing picture quite well by its copies and variations. One such formative image from Antwerp by Quinten Massys, often referred to as The Misers, has long been known, despite being lost for centuries. This picture was previously known only through mediocre black-and-white photos in picture archives, so that it too was taken to be a mediocre copy. Yet the influence of Massys’s picture in the history of genre paintings—the subject was taken up almost immediately by the painter’s son Jan Massys, by Marinus van Reymerswaele, and by Jan van Hemessen–has been recognized for some time. That picture has now surfaced and today is housed in the Liechtenstein Collection in Vaduz (fig. 1).1

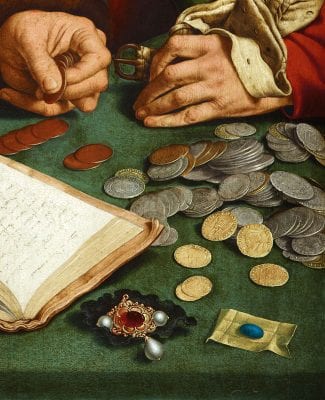

After remaining hidden, Massys’s original oil on panel now can be correctly titled the Tax Collectors. It was housed for over two centuries in the collection of Viscount Cobham at Hagley Hall, England, and was auctioned at Sotheby’s in July 2008 as “Follower of Marinus van Reymerswaele.” Marinus, however, is best known for his numerous workshop variations (seemingly numberless but of widely varying quality) on the same basic image of two caricatured men busy at their account books: Two Misers (fig. 2).2 The dismissive attribution with which the painting was shackled resulted from general neglect. The most recent casual designation was made by Lorne Campbell in London, who knew the painting only through bad photos in archives when he attributed it, in comparison to a painting in the Queen’s Collection; this determination was adopted by Sotheby’s, where the picture retained its inherited title, The Misers, as well as its lesser attribution. It had already entered the Hagley Hall collection in Worcestershire by 1800 and was first mentioned in their 1804 catalogue.

However, several distinctive characteristics of Quinten Massys are readily evident in the Hagley Hall picture but in none of the other versions. Especially revealing are the white highlights on pinkish skin tones and on the tips of fingernails. These details can be found throughout the artist’s career but are even more striking in later works. They also appear on some of the painter’s brown-skinned figures, such as the London Grotesque Old Woman (fig. 3), but also on his figure of Christ Blessing, a late work in a New York private collection (on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Clearly, the Hagley Hall picture offers a more richly layered, more finely wrought execution than either the 1514 Moneychanger and His Wife (fig. 4) or the 1517 Erasmus of Rotterdam and Pieter Gillis portrait pendants (fig. 5-6), both major dated works by Quinten Massys that have been related to it thematically and compositionally. Additionally, the painting provides another telling Massys habitus: firm, linear contours of the far side of each face, visibly reworked by the artist.

One anomaly found in the Hagley Hall paint handling might indicate a late date for the work–considerable linear underpainting below the surface of the knuckles and the wrinkled skin, particularly in the two hands on the table (fig. 7). Parallels exist in the Massys oeuvre for this more painstaking preparatory structure; it is evident in the upraised hands of Pontius Pilate in the (presumably late) Ecce Homo (Palazzo Ducale, Venice) as well as in the fuller color of that work. Thus this rediscovered picture would likely be best placed in the final half decade of Quinten Massys’s career before his death in 1530, although firmly dated works in those years are mostly lacking.

Important details argue for seeing this as a prototype image rather than a copy. The Hagley Hall picture surface reveals visible pentimenti, overpainted details changed by the artist but now revealed by time as the pigments have altered.3 These changes show up even more strongly under infrared examination. These changes include: numerous alterations in the strips of paper with seals along the top ledge of the picture; alterations to contours of the hats; and some small changes in the fingers and placement of the eyes of the writing man. Perhaps most notably, but only visible in infrared, the original Hagley Hall design reveals the trace of an earflap for the red hat, making its shape much closer to the scholar’s headdress that Massys had used earlier for his 1517 portrait of Erasmus, rather than its current, turbanlike shape. Significantly, it is only the later, altered features that were copied in their revised form by later redactors of the composition.

Several pictorial details confirm a dating from the lifetime of Quinten Massys (active 1491–d. 1530). Among the coins depicted in the Hagley Hall painting, the main gold coin, prominently shown once in obverse and twice in reverse, is a gold double ducat of Gugliermo II Paleologus, marquis de Montferrat (reigned 1494–1518). In addition an English angel coin and two unidentifiable gold German coins occupy the tabletop. Technical evidence from dendrochronology, the study of the tree rings of the painting’s panel support, also fits comfortably within the lifetime of Quinten Massys. Peter Klein has determined that the Hagley Hall panel’s three Baltic oak boards would have been felled at the turn of the sixteenth century.4 With seasoning, the earliest possible date for a terminus post quem in his opinion is “1501, though more likely after 1507”–well within the lifetime and career of Quinten Massys.5

Another surprising, unique detail of execution on the panel was revealed by technical inspection of the Hagley Hall panel: the two jewels on the table were painted above silver leaf to reinforce the luster of these two precious stones and to give them a distinctive flat finish, simulating actual polished stone. Moreover, the oval blue stone, a sapphire, at the lower right corner of the tabletop is placed at the center of a folded paper; this wrapping is still used when individual stones are transported by modern dealers in precious stones, which suggests some direct familiarity by the painter with the established customs of this trade. Indeed, the presence of such jewels within an image of financial transactions underscores the importance of Antwerp as an international trade crossroads with connections reaching across the globe. Rubies are Asian stones. Emeralds, then as now, originate largely from South America, particularly Colombia. That both kinds of gems are present in the painting shows the vast expanse of Antwerp’s trading reach, abetted by the city’s Portuguese as well as Spanish merchants who imported goods from around the globe. These prominent jewels reaffirm the other implications of wealth in the picture–from the costumes and coins to the activities of the main characters.

Inscriptions in the account book, already carefully transcribed from the Dutch by F. de Mély a century ago, identify the two figures clearly as Tax Collectors.6 The sequence of lines itemize excise receipts, respectively, for wine, beer, fish, weigh-house (weghe), market (halle), ferries (veren) for the past seven months. The activity depicted, therefore, is the business of tax farming; that is, a rented public office through which an agent pays a stipulated tax yield to the government but gets to keep the surplus, much like the later French system of the gabelle, so detested by the Revolution. The texts in Massys’s original correspond nearly exactly in account books and ledgers in copies by Marinus van Reymerswaele, including those in Warsaw, as studied by Adri Mackor,7 and with the ledger in the Paris/London Misers, as noted already by Martin Davies in the London National Gallery catalogue.8 Thus the nature of the activity can conclusively be determined as urban tax farming in both Massys and copies and variants after his original by Marinus.

Adri Mackor joins Davies to conclude that the man with the pen is actually a city official (“borough or city treasurer” in Davies’s formulation). Thus he is transcribing the accounts, writing up the receipts for seven months. Davies also credits this man with higher office because of his hat, fur trim on his jacket and his visible ring (on his right index finger), which also has a heraldic signet (unidentified) in the Hagley Hall image. Davies views the other man, facing out of the picture at the viewer, as the tax collector himself, in the uncomfortable position of being audited by the writing man. This characterization might account in part for the fact that the writing man clasps a coin in his fingers and holds a small stack of coins in the palm of his hand. He is clearly setting them out in a row and tallying the sum. Adri Mackor further denies the negative associations of the spectacles for this official, who does seem scrupulous about his task; however, he does note the “greedy grin” of the staring man.

Context and Meaning

An old Netherlandish proverb of the period declares, “a usurer, a miller, a money-changer, and a tax-collector are Lucifer’s four evangelists.”9 Massys was already the first painter to depict moneychangers, in the celebrated 1514 Louvre Moneychanger and His Wife (fig. 4).10 Moneychangers often performed the same role as bankers, according to economic historian Raymond de Roover.11 Moreover, the unrepresented fourth scoundrel, the miller, was often castigated because grain prices became a chronic sore spot in eras of fluctuating commodity prices, as was true in just this period.

The harshness of the proverb seems more appropriate to the grimacing and wrinkled faces of the figures in Marinus’s Paris and London images (fig. 2) than to the Massys original. In Hagley Hall picture, we might better see the conscientious activity of the writing man as akin to the scrupulous balancing of the scales by the moneychanger in the Louvre picture as his wife looks on. The outward, staring face of the second man and his pointing finger together suggest a further call for oversight, in which the viewer is invited to scrutinize and supervise the process as well to act as a kind of second guarantor (garant).

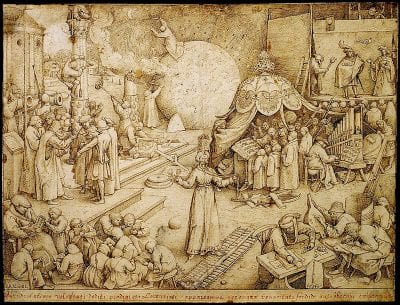

Spectacles, like those worn by the presumed city official, are sometimes regarded as the marker of moral shortsightedness, as in Pieter Bruegel’s Adoration of the Magi (National Gallery, London), where one of the bewildered onlookers is bespectacled.12 However, such glasses could also readily be associated with the virtue of Temperance, the figure of measure, number, and moderation, as also represented by Bruegel in his allegory from the series of the Virtues (fig. 8). Temperance holds a pair of similar pince-nez spectacles in her right hand, and in the lower right corner of the drawing one sees a figure of a man in archaic headdress at a table counting coins in a row as he opens a ledger. Here the spectacles of Temperance refer to her sharper powers of observation, even for objects close at hand (which for a city official practicing the virtue could mean closer inspection of coins or gemstones as much as numbers in a ledger).

Although we do not see a strongly negative tone in the Hagley Hall figure pair, neither do we see them as neutral or flattering portraits, the alternative pictorial category, exemplified by the unequivocally positive image of a financier in Jan Gossaert’s Merchant (fig. 9), or the dignified thirty-four-year-old man with money and records in a ledger by Maarten van Heemskerck (fig. 10).

The fifteenth century offers precedents for what can be called “professional portraits,” the most famous of which is the 1449 Petrus Christus Goldsmith (fig. 11).13 The ultimate source for Christus’s Goldsmith–perhaps even for Massys’s Hagley Hall picture as well, considering the archaic costumes–seems to have been a lost Jan van Eyck: a “patron who makes accounts with a factor” of 1440, documented by Marcantonio Michiel in early sixteenth-century Milan.

Of course, unlike the Christus precedent, Massys’s Hagley Hall picture does not portray contemporary costumes. The half-length presentation and use of archaic fifteenth-century costume already appeared in Massys’s 1514 Moneychanger and His Wife–from which it also borrowed the counterpoint of color between the paired figures, in which the red turban is echoed by the red shirt of the pointing man and the cooler blue of the writing figure finds its answer in green headgear. According to Margaret Scott, discussing similar headgear in Jan van Eyck’s presumed Self-Portrait (1433; National Gallery, London), this particular head covering is associated with wealth and presents an assertive signal of conspicuous consumption.14 The green millinery on his companion also resembles the hanging cloth coverings of other van Eyck portraits, such as the Tymotheos (1432; National Gallery, London).15 Surely this archaism of headgear and its seeming association, often negative, with wealth and status would have been obvious to a viewer of the following century. This outlandish and unfashionable costume also functions to distance the sitters from any present-day representation, reinforcing the effect of the figures’ ugliness, even as it clearly removes them from any suggestion of contemporary portraiture.16

The Tax Collectors served as the prototype of later genre pictures more than it represented any (double) portrait likeness of two unattractive faces, characterized chiefly by their ages and unattractiveness. Additionally, the heightened emphasis on exaggerated features of the male protagonists in Marinus’s The Misers depends upon Massys’s own acute awareness of the drawn caricatures of Leonardo da Vinci, circulated in copies.17 The earliest notable instance of the Leonardo link for Massys is the right wing of his Antwerp Lamentation triptych (1508–11), which features heads, rearranged to surround the martyred Saint John the Evangelist, clearly derived from Leonardo’s Five Grotesque Heads (Windsor Castle, no. 12495).18 Moreover, one of those same heads, a near-profile but reversed from its Leonardo model, reappears for the lustful old man in Massys’s later Ill-Matched Pair (fig. 12). This reuse of grotesques for negative male figures further suggests how much Massys should be credited with the innovation of using physical ugliness to display moral turpitude.

In another instance Massys used grotesque faces and exaggerated costume for the pendant works, pseudo-portraits in all likelihood, the Grotesque Old Woman (fig. 3) and Grotesque Old Man in Profile (fig. 13).19 The two works share the same kind of brownish skin and flabby jowls. The Old Man’s fur-trimmed robe and visible gold rings, while not as demonstrably archaic or absurd as the costume of the Woman, nonetheless suggest conspicuous wealth, and his distinctive profile echoes the familiar profile of Europe’s leading merchant-banker of the fifteenth century, Cosimo de’ Medici of Florence.20

Indeed, confirmation of the formative influence of Quinten Massys for ugly male faces, especially in a financial context, can be seen through the work of his own son, painter Jan Massys (active 1531–1573). Jan’s dated version of a grotesque (albeit bearded) money handler with an equally grotesque, brown-skinned peasant emerges–at a moment exactly contemporary with Marinus’s works–in his Tax Collector (fig. 14).21

But unlike obvious grotesques by Massys, based on Leonardo da Vinci’s caricature faces (such as the Washington Ill-Matched Pair), the Tax Collectors retains considerable ambiguity concerning its meaning. While surely neither of these men is presented as a portrait, their presentations differ. In particular, the official writing in the accounts ledger still shows a basic dignity and scrupulousness, but this attitude seems at odds with the grimace and the pointing gesture of his companion. In contrast to the Moneychanger and His Wife, the Tax Collectors lacks all suggestions of the admixture of religion, as well as justice, with the weighted scales. Additionally, it includes a new tension, suggested by the pointing forefinger and the gaze out of the image, to evoke an appeal, even a challenge, to the viewer to check those written entries.

With his Hagley Hall Tax Collectors, along with a few other works–Moneychanger and His Wife, Ill-Matched Pair–Quinten Massys essentially invented, and certainly established for posterity, the novel concept of genre painting for private collectors. The success of his innovation is obvious from the numerous copies and variants, particularly by Jan Massys and Marinus van Reymerswaele.

Theme and Variations

Starting with these works of Quinten Massys, sixteenth-century Antwerp paintings grappled forthrightly with the sudden and trenchant problems of avarice posed by the explosion of the city’s international economy.22 These acute tensions between God and mammon (Luke 16: 9–13) were first made explicit by Massys’s 1514 Moneychanger and His Wife (fig. 4). Embodying this very dilemma, the woman’s prayers are distracted by her husband’s activity. But the man is deeply preoccupied with balancing his scales in order to weigh and value the currency on his table for exchange. Even though some scholars have argued for its fundamentally critical outlook, this picture is not uncompromisingly negative, because the archaic costumes and the obsolete profession of moneychanger serve to distance any criticism of moral turpitude in financial matters from contemporary reality.23

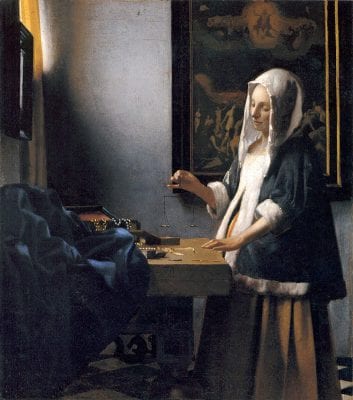

Just as in Johannes Vermeer’s later Woman Balancing Scales (ca. 1664; fig. 15), here the banker engages in a careful calibration of his scales. Despite the presence of gold coins and pearls on her table, Vermeer’s solitary woman embodies justice in the larger sense, echoed by the ultimate image of Justice, represented by a painting of the Last Judgment on the wall behind her. Indeed this message literally surrounds the Massys picture: inscribed on the lost original frame an inscription once read, following Leviticus 19: 36, “Just balances, just weights . . . shall ye have.”24

The significance of the Moneychanger and His Wife lies in how it makes a theme out of these tensions (gendered as well): on the one hand highlighting traditional religious meditation–also visible in the reading figure reflected in the small bull’s-eye circular mirror in front of a tall church steeple–and on the other the worldly activities of money-handling. In the process, Massys employed the format and rhetoric of portraiture: half-length figures sit side by side within a common space. Only three years later Massys would produce pendant portraits, Erasmus of Rotterdam and Peter Gillis (fig. 5-6), that embody a similar dialogue, but one that takes place across panels, bridging the narrow studio space between them.25 In order to invent what later generations would mold into secular genre imagery, Massys relied upon the ready model of half-length portraiture, here generalized into generic, lavishly costumed companion figures of husband and wife.26

While the next generation of painters frequently imitated Massys’s half-length innovation for their own emerging genre imagery, they also literally unbalanced his fragile equilibrium through exaggeration and caricature of the same characters and their archaic costumes. Chief among these epigones, the mysterious Marinus van Reymerswaele produced his own version (in numerous workshop replicas), Banker and His Wife (for example, those in Madrid and Munich; both works dated 1538; fig. 16-17) as well as the Two Misers (fig. 2). His images further distance the two main characters from any contemporary reference.27 Massys’s turbanlike fifteenth-century Eyckian headdress on the banker becomes in Marinus’s hands an outlandish horned sombrero with a swooping pinked cloth sash. In front of the couple not only a prominent weight box but also phallic moneybags emphatically reinforce the cupidity of their avarice. But the strongest alteration in the Marinus variant is the artist’s pointed elimination of the woman’s open prayer book; she now peers more avidly over at the scales and coins as her fingers rest upon the page of an account book. In similar fashion, her husband is already engaged in business; rather than testing his balance for probity, he is weighing a coin, testing it in order to guard against the practice of “clipping,” in which metal content is subtly shaved away from the edges or surface.28 This careful scrutiny of coin probity requires standardized weights, usually originating in Cologne; these appear prominently in a foreground weight-box on the table of Marinus’s couple. Cluttered shelves behind them in the booth prominently feature a extinguished candle, present already in the Louvre version of Massys’s Moneychanger but now a homely metaphor for the brevity of life (vanitas), perhaps even an allusion to the Foolish Virgins, who failed to keep their lamps lit while waiting for the return of the Messiah (Matthew 25: 1–13).29

The original attribution of the Hagley Hall painting to Marinus or his close follower can offer us further instruction by contrasting Marinus’s alterations to Massys’s original composition. In his two variant compositions of the Massys prototype (fig. 2), Marinus inserts still more outlandish headgear, either a Massys-like turban or else a Marinus-like florid bonnet. Consistently in these versions Marinus shows one subject’s right ear as a pointed, even distorted, gnomelike shape. While some details of the furnishings of the booth differ, in all Marinus versions a burned-down candle in its holder appears directly above the two figures, as if in echo of the Foolish Virgins as a vanitas motif. Also on the same shelf sits an open weight-box of standard measures (marked “Ceulen” after the city of Cologne, where the weights originated) alongside a small overflowing round box of paper records, some of them bearing red wax seals. The consistency of these images permits a fairly close reconstruction of the Marinus prototype Tax Collectors, which is quite well replicated in a version in Paris (Louvre; formerly Grog and Solly Collections, dated in its ledger 1549).30 This pattern also clearly shows that the most outlandish Marinus headgear is a later substitution, as is the added presence of a parrot rather than scissors behind the two principals.

Marinus van Reymerswaele also produced his own variant of this basic image in a high quality panel now in Paris, closely replicated in the London version (fig. 2).31 There the scowl of the pointing figure has become a rictus of pain, and the wrinkles of the aged figures are even more exaggerated. Because of the high quality of the London work (or its newly defined Paris prototype), it has sometimes been seen as the wellspring of all these other related images of misers, in particular by Lorne Campbell, whose analysis of the later variant with parrot in the queen of England’s collection occasioned his full, renewed analysis of the entire cluster of copies.32 Yet its varied divergences from their common features clearly indicate that it is a later variant and that it cannot be the basic source of the other images.

Indeed, methodology already exists for analyzing such related series of images, of stemmata linking related images in order to recover lost models from their descendants. This material has been employed for medieval manuscripts, whose visual series have been studied, just as their verbal alterations from a common model have been employed as a common analytical method for text recensions in literary editions.33 This pictorial genealogy distinguishes between corrupted or altered copies and iconographically accurate replications after a common model.

Moreover, although Marinus van Reymerswaele’s name and biography might have been lost to history shortly after his lifetime, especially outside the Netherlands, Massys had already received credit for the authorship of this composition in early inventories. In 1616 (September 22), the collection of Jacques Dassa mentions “a painting on panel of a tax-collector or money-changer made by Master Quinten.”34 In 1652 this same painting (or another version of it) reappeared in the inventory of Jan Meurs in Antwerp: “a painting, painted by master Quinten Metsys, showing the Tax Collectors.”35 Even in seventeenth-century Spain, the inventory of the large collection of the marquis of Leganés (1642) includes one reference (no. 31) to “another painting by Master Quintin, of a banker . . . counting coins on a table, and on it and a shelf different books and papers with seals of letters,” as well as another item (no. 328), “a painting with two bankers with papers, one writing in a book.”36 Of course, Quinten Massys was easily the most famous of these three painters, vastly better known and more celebrated than either his son Jan or Marinus van Reymerswaele; indeed, Massys was widely credited by the mid-seventeenth century as the “father” of School of Antwerp painting, and his career formed the subject of a pair of laudatory local biographies–by Franchoys Fickaert (1648) and Alexander van Fornenberg (1658).37 Thus it is hardly surprising that this celebrated painter was the one attributed by collectors with authorship of their paintings; in addition, we can note that three documented references to titles variously determine the identity of the two figures as tax collectors, moneychangers, or “bankers.”

After examining the copies and variants as well as the documentation, our reconstruction of the sequence for the production of this long-missing Massys becomes clearer. It seems logical to suppose that the principal invention–a two-figure composition of men with ugly faces engaged in some form of financial dealing–does stem from Quinten Massys– the creator of the 1514 Louvre Moneychanger and His Wife. Its status is clear as a prime object–a fountainhead of what would become secular satire in easel painting and of imagery using grotesque faces as the index of moral turpitude, as in the Washington Ill-Matched Pair. Clearly Marinus van Reymerswaele made even more grotesque variations on the Quinten Massys model of two men with a ledger and coins, and with still more exaggerated millinery in several versions, one variant (Paris, London) reversing the direction of the second figure. Marinus also repeatedly borrowed and modified other Massys prototypes, including the Moneychanger and His Wife as well as Saint Jerome in a Study. Likewise, Quinten’s painter son Jan Massys also picked up some of the same motifs: brown skin, grotesque features, and themes of financial dealing; however, his pictures (see fig. 14) show a distinctive manner not easily confused with that of Quinten, and they do not replicate the basic Hagley Hall composition nearly so closely as works by Marinus van Reymerswaele.

Quinten Massys’s picture was created in Antwerp at a time of financial crisis during the 1520s. Excise taxes, like those shown in the Hagley Hall ledger, formed the basis of fund-raising for prosperous cities in the early modern period, and they were linked to consumption. As noted above, the collection of excise taxes was auctioned off to private individuals as tax farmers, who were free to reserve the surplus income to themselves. In Antwerp, which had a reluctance to tax commerce or place tariffs on foreign trade, this decentralized form of fund-raising characterized Habsburg rule.38 In contrast to France, where great financiers took on the role of tax farming, in the Low Countries lower-level burghers took on this role. Within the specific economy of Antwerp in the final decade of Quinten Massys’s career, Antwerp experienced its own financial crisis following the change of ruler to Emperor Charles V, who from his capital in Spain increased wartime tensions with rival France, beginning in 1521.39 Immediately Antwerp trade suffered from reduced international shipping and a serious drop in tolls. This situation, compounded by the German Peasants War of 1525, which helped to cut off silver and copper shipments, led in turn to a devaluation of Habsburg currency and the imposition of cash payments for international debts. Suddenly the value of gold inflated, even relative to silver and certainly against devalued money held on account. Under these tight money circumstances, the emphatic representation of coins, especially the large gold coins, in pictures like the Hagley Hall painting, assumes even greater prominence. German silver was still being minted in France and the Low Countries, and in this period large German silver coins, led by the Joachimthaler, spread throughout Europe and encouraged trade in money itself.40 Real income for the middle classes declined, even as prices, especially grain prices, remained high and resulted in under-consumption. And this crisis situation continued without serious improvement through the 1520s and into the1530s. In the city that formed the nascent capital of capitalism, the Tax Collectors clearly recognized the potential dangers and temptations toward avarice that such professional duty could entail.

Yet this new category of genre painting also grew out of, and fully utilized, earlier conventions of portraiture, such as the half-length in a confined space of the 1517 Erasmus (fig. 6). Thus, works not intended as overtly satirical could potentially still retain some characteristics of professional or vocational portraits. For this reason the interpretations of the Massys prototype have ranged widely, including my own earlier readings. The basic ambiguity built into both the pictorial forms and the fraught subject matter of the Tax Collectors has led some scholars (for example, Leo van Puyvelde) to seek an actual portrait in the figures, whereas others (Keith Moxey) have emphasized the condemnation of folly and sin inevitable in financial dealings, at least from the point of view of humanists and rederijkers in Antwerp and elsewhere.

Excursus

Just as we consulted the Washington Vermeer, Woman Balancing Scales, to help explicate the Louvre Moneychanger and His Wife, so, too, can we view two important early works by Rembrandt as a possible extension of and comparison to Massys’s Tax Collectors. A small painting, usually called a Moneychanger or Usurer (monogrammed and dated 1627; fig. 18), shows a richly dressed, wrinkled–and bespectacled–old man studying a coin by candlelight amidst his scales, moneybags, and ledgers.41 He clearly seems the later descendant of Massys, but as in the works of Marinus, is presented chiefly with a negative cast. In this case, pseudo-Hebrew lettering on some of the papers might even expressly identify this figure as a Jew, reinforcing his negative, stereotyped image.

But Rembrandt also etched a large-scale 1639 print with an image of a Goldweigher, correctly identified as an individual portrait of Jan Wtenbogaert (fig. 19).42 As Receiver-General for the province of Holland, this sitter was also a receiver of taxes, so his official professional status is well established. Rembrandt’s print shows him within a fully described interior space with accessories. In many respects this highly detailed image offers a dialogue with and continuation of the two earlier Massys models, particularly the more positive Louvre Moneychanger, while also engaging with the print precedent of Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving, Saint Jerome in His Study. The main figure also wears a fur gown and a stylish beret, an old-fashioned sixteenth-century bonnet like that worn at times by Rembrandt himself in earlier self-portraits.43 The busy tax collector is making a record in his ledger at the moment that he is also accepting a large moneybag from a well clad kneeling young assistant; other moneybags of the same size and kind sit on the tabletop near both the ledger and the scales, which are big enough for weighing such sacks rather than individual coins. In a striking connection to the scenes by Jan Massys, a pair of older peasants behind a half-door in the left rear of the print seem about to enter the space of the room. They are humble but clearly have dressed up for the occasion, as evidenced by the man’s tall hat. Indeed, quiet dignity characterizes the conduct of all figures in the etching.

Like Vermeer’s insertion of a Last Judgment painting behind his Woman Balancing Scales, Rembrandt places into the background of his print a large framed picture, here depicting Moses and the Brazen Serpent (Numbers 21: 9), another image of divine demands for a show of faith. Indeed, this theme–according to traditional typology a prefiguration for the Crucifixion–was so closely associated with the separation of the faithful from the faithless that it formed a favorite theme of Martin Luther in his contrast between Law and Grace.44 Just as the background beggar receiving alms in Jan Massys’s Dresden Tax Collector suggests a negative counterpoint to the main scene of money-collecting, so here the background biblical reference suggests the positive representation and the professional probity of the depicted individual (someone on whom Rembrandt relied for goodwill and intervention with the court of stadholder Frederik Hendrik in The Hague). By this reckoning, the success of the sitter could easily be viewed in light of Calvinist associations of worldly success achieved with the aid of divine grace. Thus Rembrandt’s later versions of tax collecting recapitulate the same polarities within which the profession could oscillate in its visual presentations.

This later imagery still leaves considerable ambiguity concerning the meaning of Massys’s Hagley Hall Tax Collectors. While these two men are surely not portraits, as is Rembrandt’s Wtenbogaert, their pictorial presentation, particularly that of the official writing in the accounts ledger, still shows a basic dignity that seems potentially at odds with the grimace and the pointing gesture of his restless companion. Surely Massys’s Tax Collectors lacks such direct suggestion of religion and also omits the indication of justice with scales, which had suffused the earlier 1514 Moneychanger and His Wife. And the Hagley Hall picture uses its pointing forefinger and gaze out of the image to create tension and to connect with a viewer, even to challenge him to check those entries further.45

In comparison to my initial analysis (from its copies and later variants) of Massys’s Tax Collectors in a 1984 monograph on Quinten Massys and a catalogue of his work, I am now struck much more by fundamental ambiguities built into this foundational painting. The father of Antwerp painting was also the father of genre painting, and in utilizing the inherited conventions of portraiture with earlier models of costume and professional depiction, Massys inevitably carried over some of the sobriety and seriousness of that heritage. Yet he was also reaching for a new subject, examining an activity that clearly posed a moral dilemma, but that no longer was linked overtly to religion like the inscription on the original frame of the Louvre Moneychanger. Even more than the hanging scales in that same Louvre painting, the pointing finger of the Hagley Hall Tax Collectors directs our gaze to the necessary connection between wealth and its recorded measure, and ultimately to the necessary virtue of Temperance. Just as spectacles can indicate moral as well as physical short-sightedness, so, too, can a closer inspection through lenses exemplify proper measure. We viewers must follow Quinten Massys in his new experiment and learn the difficult lesson of how to see correctly.