This essay presents collaborative research related to the National Endowment for the Humanities-Arts and Humanities Research Council grant-funded project Connecting Threads, a website that brings together academics and curators across the United Kingdom and the United States who seek to contribute to wider decolonization work in the humanities and engage communities whose contributions to global cultures of textiles and fashion have historically been ignored. The Connecting Threads research team uses the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data and web applications to deepen understanding of the Madras kerchief, a large checked cotton square cloth that circulated in Afro-diasporic communities in the Caribbean during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Introduction

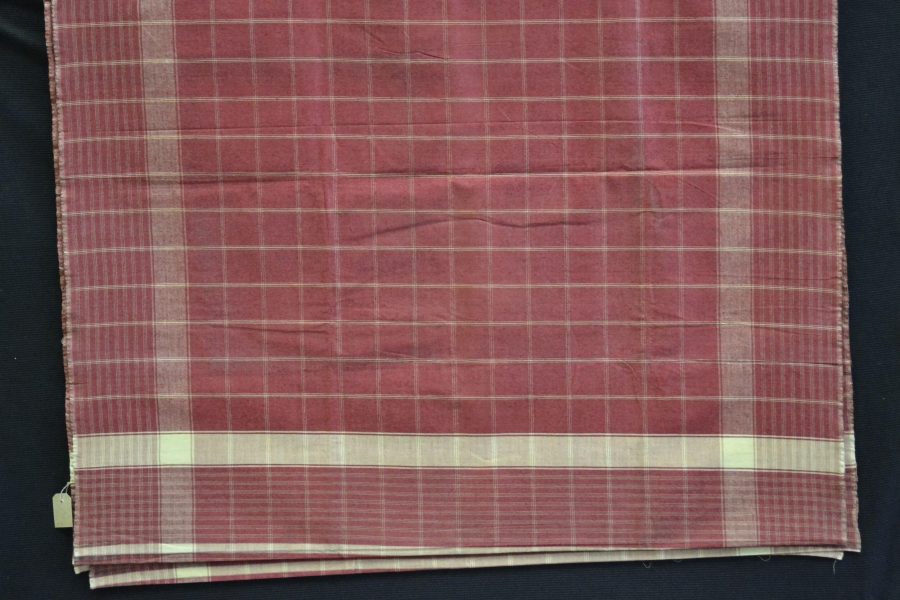

Connecting Threads (connectingthreads.co.uk) is a collaborative digital humanities project aimed at foregrounding the influence of overlooked actors in the shaping of history through fashion. It does so by concentrating on the consumption of Indian and imitation Indian fabrics by Afro-diasporic communities in the Caribbean during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The project is currently investigating the history of the Madras kerchief, which continues to be fashionable even today (fig. 1). Indeed, Madras has become a national symbol in parts of the Caribbean, while in India it serves as an emblem of heritage textile craftsmanship.

The apparent simplicity of this large checked cotton square contrasts with the complexities of its global popularity. Although established demand in West African and Afro-American markets contributed financially to the mass production of Madras kerchiefs imitations in Europe, the literature has left unattended the agency of South Indian lower-caste weavers and the tastes of African and African-diasporic communities in shaping global connections. Supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities-Arts and Humanities Research Council (NEH-AHRC) grant, Connecting Threads brings together academics and curators across the United Kingdom and the United States who seek to contribute to wider decolonization work in the humanities and engage communities whose contributions to global cultures of textiles and fashion have historically been ignored.1

Although Connecting Threads focuses mostly on the British Empire, it is in conversation with the Dutch Textile Trade Project. Historian Chris Nierstrasz has demonstrated that in order to understand the British East India Company’s evolution as a major textile trader, it is necessary to attend to the development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and their mutual rivalry within a global context.2 Both Connecting Threads and the Dutch Textile Trade Project foreground textiles as a means of understanding how people and places were connected in this era of the “merchant empires.”3 Both projects are also committed to highlighting connections that have thus far not received much attention. In the case of Connecting Threads, we are doing this by focusing on a particular type of Indian textile that was consumed by specific populations in the Caribbean. The Dutch Textile Trade Project presents data that brings together Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) textile trade records, allowing users to see how places like the Coromandel Coast in India, Batavia, and Dutch Guyana were connected in the early eighteenth century. In what follows, members of the Connecting Threads team have outlined the ways in which we find the Dutch Textile Trade Project to be useful for us and to the study of textile history and global connectivity in general.

Textiles and Global History

Scholars in a variety of disciplines have argued for the importance of textiles, especially Indian cotton textiles, to the expansion of European maritime empires. Some have looked at the issue from an economic history perspective, considering the volume of textiles exported to Europe and the impact this had on industries in Europe and South Asia.4 More recent research has considered the trade of these textiles by European companies to Africa, where they were a key commodity for the transatlantic slave trade.5 Scholars interested in the cultural impact of the movement of these goods have considered how fashions changed in the places where these textiles were introduced.6 One of the most important contributions of the Dutch Textile Trade Project is the possibility of bringing these different strands of scholarship on the economic and cultural history of textiles together.

Scholars will be able to use the information provided by the project to consider the numbers and types of textiles that moved between different sites in the Dutch empire and then match that data with visual and material sources, such as textile samples, paintings, and prints. This will serve to deepen both types of analyses: economic historians will be able to assess how qualitative factors such as color, pattern, and texture impacted these exchanges, and art historians will have access to the kind of quantitative data necessary to support arguments predicated on visual sources. This latter point is a particularly important one for the Connecting Threads project, as we rely on European depictions of life in the Caribbean to try to understand what types of textiles were consumed by the African diasporic population in the region.

One well-known source of such depictions are the works of Agostino Brunias (ca. 1730–1796) who painted life in the ceded islands of Dominica, St. Vincent, Grenada, and Tobago (fig. 2). Brunias was commissioned to present life in these islands as idyllic, thereby encouraging investment in plantations by the British, especially in the wake of the abolition movement.7 The problematic patronage of Brunias’s work complicates any use of his paintings to identify what people might have actually worn and how. However, with the help of data provided by the Dutch Textile Trade Project, we can begin to assess to what extent the visual record is accurate. The data helps us see the sheer number of Indian textiles that were in circulation in the world in the eighteenth century and also to trace specific categories of cloth, such as guinea cloth, from South India to Dutch Guyana in the Americas. We know that the various East India Companies followed similar patterns of trade, exchanged many of the same commodities, and competed for the same markets. The Dutch data provided by the Dutch Textile Trade Project can help projects like ours use information about the types of textiles and their volumes to be more confident in our assertions about the types of Indian cloth available in the Caribbean and circum-Caribbean—especially as, to date, we have found a dearth of surviving pre-nineteenth-century examples of Indian cloth with documented provenance linked to the Caribbean.

Textiles, Terminology and the Dutch Textile Trade Project Dataset

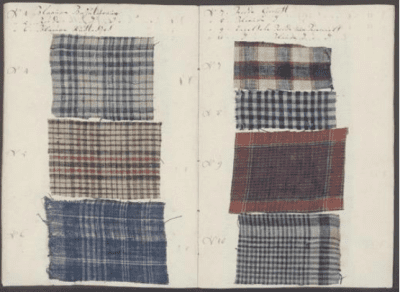

Textile history studies are rife with challenges of terminology. Any one textile type may have dozens of names across different production and consumption markets; the characteristics of that textile may fundamentally change depending on time, place, and agent; imitations, both overt and covert, may complicate understandings of origin and definition; and, as with all consumption histories, records themselves are not infallible. Contemporary traders and consumers themselves were subject to mistakes of terminology and understanding. As a result, researchers are often limited to informed guesswork, patched together from whatever consistencies they are able to glean across extant identified examples, trade records, swatch books, contemporary accounts, and visual depictions. Such has certainly been the experience of our project team in researching the history of the Madras kerchief.

As such, a database that enables access to both value and volume data, as does the Dutch Textile Trade Project, offers researchers the extraordinary opportunity to undertake substantial comparative analysis in a way that is rarely possible in textile history. The ability to view all the trade names found across years of Dutch textile trade both challenges and illuminates our understandings of the cloth being traded. Take, for example, the differentiation between guinea cloth and gingham in the ledgers, which confirms that these fabrics were delineated for the purposes of the Dutch trade. In style and substance, the two types of textiles may have—in some contexts—been very similar, and indeed the two terms are often conflated in discussions of checked and striped trade cottons from India (ginghams at times being a category of so-called “guinea cloth/guinea stuffs” and at others being distinct from it).8 The overlaps and differences in the destination markets of these two varieties, as seen in the database, might support either categorization. According to the database, guinea cloths were sent to Angola, Benin, Ghana, Guyana, Indonesian Timor, Iran, Jakarta, Japan, Java, Maluku, Mauritania, the Netherlands, Sri Lanka, Sumatra, Malaysia, and Yemen, while gingham was sent to essentially the same markets, excluding those of Angola, Benin, Ghana, and Guyana. This might suggest that either ginghams were considered distinct from guinea cloth when it came to the West African market, or that—for that market—a clerical differentiation was not made between the two. Further exploration of the modifiers listed for the gingham and guinea cloth orders, as included in the database, can shed light on these distinctions, as the Dutch Textile Trade team has already proven through their excellent explorations of terminology in their visual textile glossary.

For the Connecting Threads project, the dataset allows us to pose a diverse range of questions regarding the cotton textiles that we are examining, especially checked textiles and kerchiefs such as guinea cloth, gingham, and rumal (roemaal) (fig. 3). These questions range from analyzing how many of these textiles were exported from the Indian subcontinent to other parts of the world to visualizing the ebb and flow of circulation of these textiles over the first quarter of the eighteenth century in VOC-engaged markets. For example, we learn that there was an almost equal enthusiasm in sourcing gingham from regions that lay within Bengal (14,6434 pieces) and the Coromandel regions of Southeastern India (18,7009 pieces), while only one entry shows it being sourced from the western Indian major port of Gujarat (three hundred pieces). This was not the case with some of the other textiles, like guinea cloth, that when sourced from India were sourced mostly from Southeastern India but were also sourced in large numbers possibly from various centers in Southeast Asia. While economic historians have generally identified VOC activity in India as being rooted in their strongholds on the eastern part of the subcontinent, the details of which textiles were being sourced from where is an important contribution from this dataset that challenges ideas about where the VOC was active in the Indian subcontinent and across Asia and Africa.

More significantly for our project, the dataset allows us to access descriptive data from VOC archives that help fill gaps of knowledge surrounding some of these textiles. For example, we get a sense of how Europeans were identifying and classifying textiles for export, which then helps us disambiguate the use of terms that upon first analysis may appear to be used interchangeably. From the VOC dataset, it becomes clear that a textile like gingham was classified not only by quality—fijn (fine) or gemeen (ordinary)—but by many other categories as well: design (effen [plain], geruit [checked], gestreept [striped]); color (rood [red], dronggangs [brown-red]); or where they are from (effen Bengaals or effen Coromandels). We learn that not only were textiles exported as is but also stitched, as seen in gingham materials marked as fijn geruit onderbroek (fine checked underclothes) or onderbroeken (underclothes). While there is a differentiation of gingham as fine and coarse, it is not marked as anything but cotton, whereas guinea cloth—also marked as fine, coarse, and raw—is classified as linen in addition to these other categories. This gives us further ways to distinguish between these textiles and disambiguate available records from other East Indian Companies and cloth traders from India and other regions that were engaged in the trade of these textiles.

Madras Kerchiefs and Dutch Textile Trade Project

The scale and scope of the Dutch Textile Trade Project dilates the context that Connecting Threads deepens. Connecting Threads has identified in the Madras kerchief a vehicle to qualitatively foreground hitherto marginalized south-to-south connections. However, the Madras kerchief was just one of the hundreds of categories of Indian cottons traded across Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia that radically transformed global fashions (and history). The broader context is quantitatively affirmed by the Dutch Textile Trade Project. Its infographics, based on a systematic examination of the VOC and WIC commercial routes, communicate at once the growth and composition of the highly competitive early-modern long-distance trade in which the Madras kerchief thrived as a product.

The chronological focus of the Dutch Textile Trade Project (currently 1700–1724, with plans to expand) is complementary to Connecting Threads. In particular, the absence of items labeled as Madras kerchiefs in the Dutch context for the given period informs our findings. At present, we have not identified Madras kerchiefs (named as such) in any of the consulted sources prior to the 1760s and 1770s. The seeming terminological gap in both research projects aligns with investigations on the French East India Company and French Indian Colonies, including the early study by G. G. Jouveau-Dubreuil, who claimed that the Madras kerchief was only adopted after 1750 because “from 1600 until 1750 they were always called Pulicat handkerchiefs.”9 Legoux de Flaix, meanwhile, stated that by the end of the eighteenth century the term “Madras kerchief” was mistakenly used to talk about Pulicat kerchiefs, despite none being manufactured in Madras.10 Yet, by the 1770s, sources distinguish between Madras and Pulicat kerchiefs.11 What all these findings suggest is that “Madras kerchief” may be a constructed marker whose origins we should probably pin down to the mid-eighteenth century, in connection with the development of import-substitutions by European manufacturers marketing their products as Indian, and with mercantile companies disputing their grip over textile-producing regions in India and over the Atlantic markets. In contrast, what the Dutch Textile Project has identified are kerchiefs labeled as bandannas and rumals (roemaals) from Bengal and the coast of Coromandel.12

Despite the absence of Madras kerchiefs in the Dutch Textile Trade Project database, we have been able to use the data to explore which textile names resonate most with our understanding of these textiles as they existed at the time, such as ginghams and guinea cloth. Using these names, we are further able to track what proportion of the selected textiles were exported through Dutch operations year by year, and to some extent where they were exported (allowing for unknown quantities traded as re-exports). By comparing these data with the data collected by us and others on the British East India Company trade, as well as early forays into the French East India Company trade, we are able to fill in a picture of how Madras kerchiefs changed hands and, by extension, find more clues as to their design, production, and consumption histories.

Conclusion

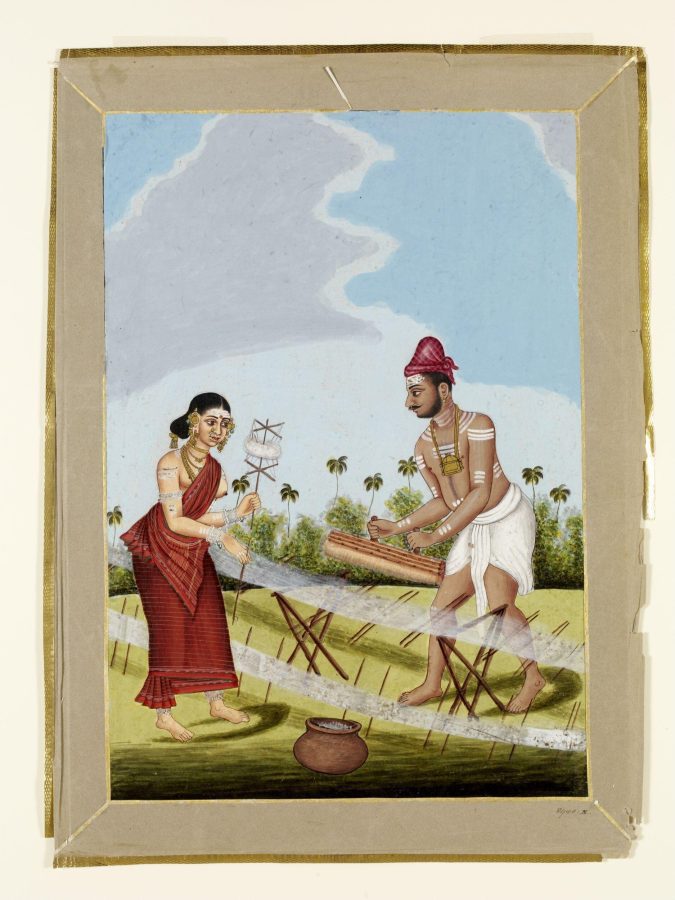

The textiles examined in Connecting Threads and the Dutch Textile Trade Project are culturally composite products. We can see this in the Madras kerchief, whose definition can only be understood as a result of a process in which producers in Southeastern India (fig. 4), European traders, and global consumers equally participated, either freely or forcefully, in furnishing it with meaning and value. Yet objects such as the Madras kerchief have remained outside the focus of a myopic scholarship and public knowledge. Together, both projects offer scholars, students, and connoisseurs tools to challenge Eurocentric historiographic traditions. By mapping global circulations, highlighting diverse markets, and setting paintings in dialogue with textile swatches, the Dutch Textile Trade Project displaces center-periphery art-historical discourses. It advances the “horizontalization’” of art history’s hierarchy of artifacts.13 Connecting Threads unfolds the history of the Madras kerchief as a shared space where eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Indian weavers met Black Caribbean consumers. Together the two projects intervene in and disrupt Eurocentric tropes in the writing of (fashion) history.

The Dutch Textile Trade Project is impressive for the amount of data collected, and the intended accessibility of this data through the platform interfaces make this project’s goals even more laudable. The visualizations generated by the platform give users aerial views of decades of international trade while providing multiple “ways-in” to engage with deeper research—the ultimate objective for any public humanities resource. Overall, this tool will be valuable to any researcher grappling with tangles in textile history.