This article presents a new attribution and dating for a painting of Judith with the Head of Holofernes. A monogram, decorative elements, and technical features strongly suggest that it was made by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen around 1525–30.The decorative details are placed within the context of contemporary sketchbooks and pattern books. The painting technique — including preparatory layers, brushwork, and the depiction of fabrics — is discussed in relation to other paintings by Vermeyen and Jan Gossart. The subject matter of the powerful female figure gives clues to the painting’s likely patron: Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands.

In this dramatically assertive image (fig. 1), the Old Testament figure Judith is dressed as a classical heroine in antique-style, pseudo-Roman armor, yet “decked . . . bravely, to allure the eyes of all men that should see her” (Apocrypha, Judith 10:4). With her large, masculine-looking hands, Judith brazenly wields the sword she has used to sever the head of Holofernes (Judith 13), the Assyrian general whose troops had captured the Jewish city of Bethulia, and grabs the locks of her victim’s hair. Self-absorbed in thought, she reflects on her triumphant deed. As a result of her actions, and demoralized by the loss of their leader Holofernes, the Assyrians fell into the hands of the Jewish armies.

This painting in a private collection was long considered a work by Jean Bellegambe, the Franco-Flemish painter from Douai.1 However, visible on the tiny shield on the guard of the sword is the unmistakable — albeit altered — monogram “IC” (in ligature) of Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen (Beverwijk, near Haarlem, ca. 1502–1559 Brussels). The infrared reflectogram of this monogram shows its original form, which at a later point was modified for unknown reasons when the “C” was overpainted to make an “O” (compare figs. 2 and 3).2 Here we find the intertwined letters “IC” in the form Jan used to sign his prints and only one other painting, The Holy Family, where he painted his “IC” monogram beneath the inscription “IOHNES VERMEI PI[N] GEBAT” (fig. 4).Further confirming Vermeyen’s authorship of the Judith is the damaged inscription on the shaft of the sword (fig. 5). It reads “IAN BE . . . [?] M” followed by a star. Although the IAN confirms the artist’s first name, the second word is unintelligible; possibly it once indicated, in abbreviated form, “Bevervicanum,” the Latin form of Beverwijk, Vermeyen’s birthplace.

The dating of the painting to around 1525–30 is supported by the painting’s relationship to Vermeyen’s other early works, namely, Cardinal Érard de la Marck and the Holy Family diptych of circa 1530 (discussed below). In addition, the details of Judith’s antique-style, pseudo-Roman armor and headdress also suggest this date, as they are similar to decorative features that appear in contemporary sketchbooks and pattern books. Very close to Vermeyen’s ornamental motifs are those found in the earliest known sketchbook from the Netherlands, namely, the so-called Berlin Sketchbook attributed to Jacob Cornelisz. van Oostsanen and his workshop.3 The pattern on the bodice of Judith’s cuirass is comparable to various decorative forms found in this sketchbook, such as the winged angel’s head (folio 13v; fig. 6), and mirrored dolphins (birds in Vermeyen’s painting) whose tails turn into sprawling acanthus leaves, simulating volutes (folios 1v, 13v, and the top of 46v; fig. 7). Two folios in this sketchbook are dated 1523 (folio 13v) and 1524 (folio 47r), and other evidence indicates that some of the designs date into the 1530s, giving an indication of the general period of its use.4 Some textile pattern books from the 1520s and 1530s, namely Peter Quentel’s Eyn Newe kunstlich moetdelboech alle kunstner zu brachen of 1532, also show analogous features, including cherubs, stylized leaves, and dolphins, though none is as refined as the pattern in Judith’s bodice.5

One of the earliest known printed pattern books for artists is Ein frembds vnd wunderbars Kunstbuechlin, published in Strasbourg in 1538.6 These designs show antique-style armor, ladies’ decorative headdresses, hand gestures, column bases, etc., and are based on earlier sources, many of which derive from late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century German and Netherlandish art. Several of the patterns are quite similar to the headdress, armor, and even hand poses of Judith in the painting and confirm the avid interest at the time in the all’antica style (figs. 8, 9, 10).

To date, less attention has been paid to the paintings of Vermeyen than they merit. Two early articles, one by Otto Benesch focusing on Vermeyen’s portraits and another by Kurt Steinbart, attempted to bring some clarity to the painted oeuvre.7 Hendrick Horn’s monograph of 1989 concentrated more on the great Battle of Tunis series — Vermeyen’s important tapestry designs commissioned by Charles V — and less on the paintings, which by the author’s own admission are not presented as a catalogue raisonné.8 A 2008 Burlington Magazine article on Vermeyen’s Cardinal Érard de la Marck and the Holy Family diptych, the 2010 catalogue of the works of Jan Gossart (ca. 1478–1532) and the accompanying exhibition in New York and London — which called attention to the painter’s significant influence on Vermeyen9 — and now the rediscovered autograph Judith with the Head of Holofernes once again urge a reconsideration of the artist’s early paintings.

A number of technical and stylistic parallels can be drawn between the Judith painting and Vermeyen’s Cardinal Érard de la Marck and The Holy Family (figs. 11, 12).10 The Cardinal and the Holy Family underwent conservation treatment in 2006–7,11 were included in the exhibition Prayers and Portraits: Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp) in 2006–7, and were subsequently the subjects of the previously mentioned Burlington Magazine article.12 They were probably pendant paintings that hung next to each other on a wall, rather than being a conventional folding diptych. They were painted when Vermeyen worked for the court of Margaret of Austria in Mechelen and until now have been thought to be Vermeyen’s earliest autograph paintings. It has been suggested that prior to this period of employment, Vermeyen may have trained with Jan Gossart.13 Although there is no documentation of this, the stylistic evidence does support the influence of the older master on the younger one. Indeed, the right half of the diptych of Cardinal Érard de la Marckand The Holy Family derives from Gossart’s Prado Virgin and Child,14 even exaggerating the muscular, Herculean Christ Child beyond the model and the Mannerist tendencies of composition and form (compare figs. 12 and 13). In addition, Vermeyen’s Judith appears to take inspiration from Gossart’s Mary Magdalen (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).15 Both are similar tightly cropped compositions, where at the left Judith boldly grasps her sword as the Magdalen embraces her unguent jar. The two women are dressed in a highly decorative style with jeweled adornments, elaborate headdresses, and braided hairstyles — Judith’s fluttering veil mimicking the Magdalen’s trailing hair at the right. In particular, both women express an unnerving eroticism. As we shall see, there are also features of the painting techniques of Gossart and Vermeyen that link the two artists.

Some of the materials and techniques that Vermeyen employed in the Judith are strikingly similar to those of the Holy Family and the Cardinal. The three oak panels are of comparable size.16 It appears that the original format of the Judith panel has not been changed significantly, apart from being slightly trimmed on one side (fig. 14).17 It is difficult to determine for certain whether it was painted within a frame; some of the paint that approaches the edges of the panel is not original.18 The Holy Family also seems to be close to its original format and was painted while in a frame, as suggested by unpainted margins around all four edges (fig. 15).19

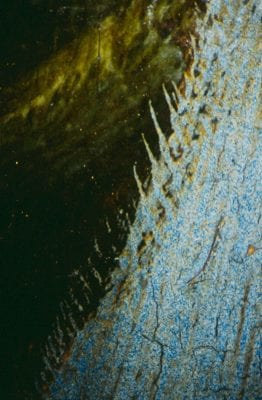

All three works have a white ground layer, and a typical composition for a ground from this period would be a mixture of chalk and glue. Under the microscope, fine parallel lines are visible in the ground of the Judith, especially in brown passages like her headdress, where the paint is abraded (fig. 16). Comparable lines can be found in the flesh tones of the Holy Family (fig. 17). Microscopic lines in the ground are not necessarily a specific or intentional part of Vermeyen’s technique; they are often attributable to scraping marks made by a knife during the smoothing of the ground, or by a spreader used during the application of the ground.20 They have been found in the works of other artists, including Jan Gossart.21

Another intriguing technical feature that links the painting techniques of Vermeyen and Gossart is the application of a flesh-colored layer on top of the ground but beneath the paint layers: a so-called priming or intermediate layer.22 A rather opaque pink layer — containing lead white, red lake, vermilion, and some black particles — was found to be present beneath both the Holy Family and the Cardinal.23 It underlies the whole surface of both paintings, and it was applied before the underdrawing.24 The pink tone was very important for the very direct and efficient way in which Vermeyen built up the flesh tones.25 He also let it shine through in the heavens in the Holy Family and in the Virgin’s sleeve. Without a thorough technical overview of Vermeyen’s oeuvre, it is difficult to know whether the all-over pink priming is a technique he used consistently, or whether it was used in an isolated case for the Holy Family and Cardinal paintings, perhaps in response to the technique of Jan Gossart.26

If the Judith indeed predates the two pendant paintings, perhaps it also precedes Vermeyen’s experimentation with pink priming beneath the whole surface of the painting. Many parts of the Judith composition are based on a pink tone: particularly the flesh and the sleeves. The flesh tones are rather thinly and efficiently painted, relying on a pink base tone with thinly applied highlights and brown shadows on top; unfortunately these thin upper layers have become abraded over time and have been retouched in many places. Under the microscope, the base tone of Judith’s skin seems to be made of a mixture of pigments: two different types of red (probably red lake and vermilion), alongside black and white particles (figs. 18, 19).27 This pigment mixture is very similar to the one used in the priming of the Holy Family and the Cardinal, although it should be noted that this is a relatively common composition for flesh tones in this period. To paint the body of the Christ Child in the Holy Family, Vermeyen used a very efficient and direct technique. He exploited the tone of the pink priming, and needed only to apply thin highlights and shadows on top and blend them together; this is very similar to the technique used in Judith’s skin.28 However, it is unclear whether a pink priming layer underlies the entire surface of the Judith paintings; perhaps it is only isolated to the areas of flesh. Due to the condition of the painting, it is difficult to assess how far the pink base tone or intermediate layer extends. Small losses in the background and along the edges were examined under the microscope, and these did not appear to show a pink priming between the ground and paint layers.

There are many similarities in paint application that can best be seen under the microscope, or in photomicrographs. In the Holy Family and the Cardinal, tiny hatched brushstrokes along the edges of fabrics give the impression of a hairy or wooly texture, especially along the edge of the Virgin’s blue robe and the cardinal’s hat (fig. 20).29 In the Judith painting, some areas — eyelashes, eyebrows, and the border around her breastplate — reveal similar refined parallel hatching (see fig. 18). A more blended form of feathery brushwork can be found within the shot silk fabric of her sleeves, which are described in greater detail below. This type of feathery brushwork, where one color is blended wet-in-wet into another with a light touch, connects Vermeyen’s painting technique with that of Jan Gossart.30

Vermeyen often used glazes in lower layers of his painting, then applied fine details on top when these glazes were dry. This technique appears to have been used in the fringe at the top of Judith’s sleeve: deft zigzags of blue paint were applied on top of a glazy pink underlayer, which shimmers through between the blue brushstrokes (fig. 21). Presumably after both of these colors were dry, Vermeyen applied dry yellow lines on top. He used a similar technique in Judith’s fluttering headscarf (see fig. 16). The distinctive color combination of a glazy (oil-rich) brown base with green and pale yellow highlights is also present in the cloth that the Virgin holds around the Christ Child in the Holy Family. Presumably both are meant to depict silky lightweight fabrics. In the yellow highlights, the paint seems to “resist” the layer underneath, probably because it was applied on top of a glazy underlayer that was relatively dry (fig. 22).31 In both paintings, it is possible that deterioration has caused changes in color, but examination under the microscope suggests that much of the brown glaze is indeed a brown paint rather than a discolored green. In the Holy Family, there are some remains of a greenish mid-tone.

Another interesting fabric is represented in Judith’s sleeves. The combination of pink and green are likely meant to represent changeant, or shot silk.32 This type of fabric assumes one of two colors, depending on the angle of the viewer’s eye to the surface of a given part of the textile. The position of the colors in the changeant sleeves in the Judith painting is accurately observed: Vermeyen used green for fabric folding away from the viewer at a sharp angle and dark pink for folds that are more parallel to the viewer. This optical sophistication is uncommon in paintings of this period, which often relied on formulas and visual “tricks” to paint shot silks.33 Although the sleeves in Judith with the Head of Holofernes are very damaged and most of the green highlights have been heavily retouched, Vermeyen’s technique for painting shot silk is visible in a few areas under the microscope.34 On top of a glazy pink layer, he applied opaque pink and green tones. The edges of the opaque areas are feathered with tiny hatched brushstrokes. Where the two colors occasionally meet, they have been blended into each other in a back-and-forth motion (fig. 23). This back-and-forth effect executed with two colors while they are still wet was also observed in the Holy Family.

In addition to the pink and green changeant sleeves, other combinations of pink and green seem to recur throughout the painting. For example, in the trim of Judith’s breastplate, a green underlayer is visible under abraded pink paint (fig. 24). Remarkably, the background would also have played into this pink-and-green color combination: the area around the figure was originally an intense dark green. Several paint losses in the background and along the edges of the panel show remains of a green layer, which is now completely hidden beneath a flat black layer of paint.35 Assuming the background was originally a dark green, it would have created a dramatic yet harmonious contrast with the flesh tones. Perhaps its effect would have been similar to the curtain that connects the Cardinal and Holy Family paintings, and to the background of Vermeyen’s portrait of Jean Carondelet from circa 1530 (Brooklyn Museum of Art).36

When considering for whom this painting of Judith, expressing female power, wisdom, and fortitude, may have been painted, a likely candidate comes to mind — Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands. It may well have been through Jan Gossart or perhaps Bernard Van Orley (ca. 1491/92–1542) that Vermeyen was introduced to Margaret, who held her court in Mechelen. He must have entered the service of Margaret in 1525, for a document of 1530 petitions the regent for back pay for a period of about five years, indicating that Vermeyen had already been working for her.37 During this time, Vermeyen seems to have been mostly engaged in making portraits of the royal family and other nobles, such as the Portrait of Cardinal Érard de la Marck that with the Holy Family formed a diptych which belonged to Margaret.

The importance of the widow Judith as a model of strength and feminine virtue for Margaret of Austria and the iconography of the Burgundian-Habsburg court cannot be underestimated. The reminders of Judith’s importance as a just, vigorous, and brave ruler took many forms. Some of these were ephemeral, such as the tableaux vivants devoted to Judith that were performed at the official entries of princesses, such as Margaret of York, Mary of Burgundy, and Juana of Castile, into Netherlandish cities.38 Margaret of Austria owned a Judith tapestry (no longer extant) that was originally part of her trousseau for her marriage to Juan of Castile, and when she returned to Flanders after Juan’s death, the tapestry accompanied her.39 Possibly commissioned by Margaret from Bernard van Orley (her court painter), although not mentioned in the inventory of her possessions, was a tapestry of the Triumph of Virtuous Women that survives only as a petit patron (Vienna, Albertina Museum, inv. no. 15463).40 Featured in the foreground before the triumphal all’antica chariot are Jael killing Sisera, Lucretia committing suicide, and Judith with the head of Holofernes on the tip of her sword. Margaret’s court sculptor, Conrad Meit, produced one of the masterpieces of Renaissance sculpture, a Judith with the Head of Holofernes (Munich, Bayerische Nationalmuseum), circa 1525–28. Although it is not listed among Margaret’s belongings, it certainly reflects courtly taste and was most likely commissioned by a woman for whom Judith was a noble exemplar.41

Margaret’s library contained books on virtuous women, among them Giovanni Bocaccio’s De femmes nobles et renomées (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Fr. 12420). Judith has a featured role in one of the most influential texts of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the Parement et triumphe des dames, written in 1493–94 by Olivier de la Marche. Here the author gives lessons to a noble lady of the virtues of humility, wisdom, loyalty, fidelity, and so forth in prose stories of famous virtuous women. Margaret of Austria owned an early version of the text, published between 1495 and 1500 (Brussels, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, ms. 10961-70).42 In 1509, Agrippa of Nettesheim dedicated to Margaret his treatise De nobilitate et praecellentia foemini sexus, where he notes that Judith “depicted herself as an example of virtue, which should be imitated not only by women but also by men,”43

Barbara Welzel has pointed out that Judith was first considered as the ideal of the Christian woman44 but became as well an important figure of identification for princesses, serving as a political exemplum.45 Just as Judith saved her people from the Assyrians, so, too, did Margaret defend her people in a politically active role. Her success in this endeavor was acknowledged in a monumental woodcut by Robert Péril (Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. no. 849-21), showing the genealogy of the Habsburgs, which praised Margaret as: “the Regent and sovereign of the Low countries, which she wisely ruled for Emperor Charles, her nephew; she opposed the enemy with the force of weapons and transferred the lands of Friesland, Utrecht and Overissel into the following of his majesty [Charles V].”46

In terms of Margaret’s remarkable political acumen, a singular event comes to mind that may have a specific connection to Vermeyen’s Judith with the Head of Holofernes. In August of 1529, around the time of the painting’s presumed date, Jan Vermeyen accompanied Margaret to the signing of the so-called Paix des Dames or Ladies’ Peace, otherwise known as the Peace of Cambrai: the most extraordinary diplomatic achievement of the regent’s career. Meeting her sister-in-law Louise of Savoy (mother of Francis I) almost in secret in Cambrai, Margaret — representing her nephew Charles V — negotiated a peace between the French and the Habsburgs. This treaty, which included the arranged marriage of Eleanor of Austria (sister to Charles V) to Francis I, ended, at least for a time, the fighting between the forces of King Frances I and Emperor Charles V. An obvious parallel exists between Margaret and Judith: two virtuous and powerful women, who managed to find a solution to the lust for battle of men and nations and create peace. Whether this painting commemorates a specific event or generally celebrates the heroic achievement of one woman, it is certainly a product of the milieu of Margaret of Austria’s court.